Translate this page into:

Theoretical calculation of the adiabatic electron affinities of the monosubstituted benzaldehyde derivatives

⁎Corresponding author. z.safi@alazhar.edu.ps (Zaki S. Safi)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

In the current study, several computational models were examined to calculate accurate adiabatic electron affinity (AEA) of twelve m- and p-monosubstituted benzaldehyde derivatives. The examined models are as follows: (i) composite high-level ab initio (G3B3, G4, CBS-Q, and CBS-QB3), (ii) Three hybrid DFT approaches (B3LYP, CAM-B3LYP, and wB97XD) with two basis sets (6–31 + G(d,p) and 6–311++G(2df,2p)) and (iii) single point calculation using fifteen DFT approaches with 6–311++G(2df,2p) at the B3LYP/6–31 + G(d,p) geometry. Several statistical descriptors were computed to validate the calculated AEAs based on the available experimental results. Results revealed that G3B3 and CBS-QB3 are the most accurate result, while G4 and CBS-Q methods yield less accurate ones. Also, the wB97XD and CAM-B3LYP in combination with 6–311++G(2df,2p) able to calculate accurate AEAs. Low CPU time single point calculation strategy by using wb97 and wb97X approaches can compute AEAs value as accurately as G3B3 and CBS-QB3 methods. The AEAs of other several monosubstituted benzaldehydes were also predicted by using the wb97, wb97X, and wb97XD. The effect of the nature and position of substituents on the natural spin density and natural charge is also studied and discussed.

Keywords

Adiabatic electron affinity (AEA)

Natural spin densities

Benzaldehyde

Density Functional Theory

ab-initio methods

1 Introduction

Electron affinity, ionization potential, proton affinity and basicity are not only assessing in estimating the capability of atom or molecule to accept proton and donate electrons, but also play a crucial role in chemistry, environmental chemistry, proton transfer and electron-transfer processes that occur in gas, liquid or solid phase (Safi and Omar, 2014; Safi and Wazzan, 2021; Safi et al., 2022). Generally, the change in energy associated to the attachment of an electron with the chemical system is known as the electron affinity (EA).

Adiabatic electron affinity (AEA) is directly related to the energy required to add an electron to an atom or a molecule. The stronger the attachment, the more energy is released. Unfortunately, experimental measurement and/or accurate theoretical calculation of EA are often not easy, and several techniques are experimentally available to measure electron affinity (Modelli, 1998; Symons and Petersen, 1978; Marshall, 1985), such as low-energy electron transmission spectroscopy (ETS) (Modelli, 1998), electron spin resonance (ESR) (Symons and Petersen, 1978) and Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry (FT-ICR) (Marshall, 1985). On the other hand, many computational methods have been used to calculate the EAs of the chemical system (Yang, 2021; Miller, 2022). High-level ab-initio and post Hartree-Fock methods require very long CPU time and they are computationally cost, and they are able to compute accurate EAs for atoms and small molecules only, with an error of 1–3 kcal/mol. An alternative approach is to use the DFT method, which is one of the most powerful computational methods available for computing the EA, especially for medium and large molecule, with an estimated error of 4.6 kcal/mol (0.2 eV), compared to the experimental ones (Rienstra-Kiracofe, 2002). Electron affinities of uracil and some of its derivatives were calculated using DFT method (Li et al., 2002), and a comparable EAs values with the experimental values were achieved. Fry et al (Hicks et al., 2004) determined computationally the EAs of monosubstituted benzalacetophenones (Chalcones) using hybrid B3LYP approach with 6-31G(d) basis set. The EAs of some fluoro-p-benzoquinione derivatives were computed by using the G3(MP2)-RAD method, and well agreement with the experimental results was obtained (Namazian et al., 2008). The EAs of formamide and its methylation derivatives were determined by using different several computational methods such as DFT, ab initio HF and Moller-Plesset perturbation theory (MP) at 6–311++G(d,p) basis sets (Lu, 2011). Cooper et al (Cooper et al., 2012) determined the EAs values for six common explosives using different composite ab initio methods and some hybrid DFT methods, and they found that MP2 and B2PLYPD methods predicted EAs as accurately as CBS-QB3 approach. In comparison to the experimental data, the many-body Green’s-function method predicted accurate ionization potential and electron affinity values (Heßelmann, 2017). The CCSD(T)/CBS//B3LYP/aug-cc-pVTZ and the G3 models were used to calculate accurate EAs in comparison to experimental results (Miller, 2022).

For this work, benzaldehyde and some of its derivatives have been chosen, which have several applications in chemistry, pharmacy and agriculture. One of the largest applications of the benzaldehyde in chemistry is in the production of certain polymeric materials. In addition, it can be used in tanning and preserving materials, and as fungicide and insecticide. Recently, the proton affinities, gas-phase basicity, vertical ionization potential and vertical adiabatic ionization potential and adiabatic ionization potential have been calculated for eight benzaldehyde derivatives (Safi and Wazzan, 2021; Safi et al., 2022). The EAs of benzaldehyde and its derivatives have been experimentally estimated to range from 9.09 – 9.9 kcal/mol (Zlatkis, 1983). Pluharova et al (Pluharova, 2012) showed that the calculated EAs are sensitively basis sets dependent.

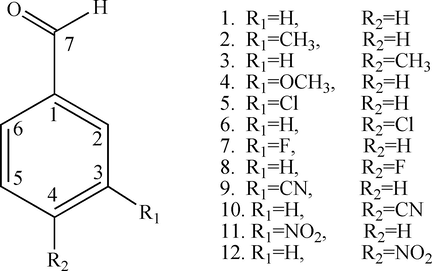

In this study, three main objectives will be considered to achieve. The first goal is to calculate the AEA for twelve monosubstituted benzaldehyde derivatives (Fig. 1) by using three different computational strategies and the accuracy and the validation of the different strategies will be statistically approved based on the available experimental data. The second aim was undertaken to use the most accurate and economical strategy to calculate the AEAs of an additional seventeen benzaldehyde derivatives whose AEAs have not been determined theoretically and experimentally to the best of our knowledge. Finally, the nature of the substituted groups and their meta- or para- position are examined and discussed.

Chemical structure of the benzaldehyde derivatives.

2 Calculation details

Three different computational strategies were used to calculate the AEAs of the twelve benzaldehyde derivatives. The first strategy is based on performing four composite high-level ab initio methods G4 (Curtiss et al., 2007), G3B3 (Baboul, 1999), CBS-Q (Ochterski et al., 1996) and CBS-QB3 (Montgomery, 2000). Performing a full optimization processes of the neutral species and their anion radicals using three hybrid DFT methods (B3LYP (Becke and Density-functional thermochemistry. III., 1993), CAM-B3LYP (Yanai et al., 2004) and wB97XD (Iikura, 2001) with 6–31 + G(d,p) and 6–311++G(2df,2p) basis sets is the second strategy. Finally, the third strategy depends on carrying a single point calculation using several DFT approaches with 311++G(2df,2p) basis set at the B3LYP/6–31 + G(d,p) geometry. The selected DFT functionals are as follows: B3LYP (Becke and Density-functional thermochemistry. III., 1993), B3PW91, CAM-B3LYP (Yanai et al., 2004), BMK (Boese and Martin, 2004), B97D (Grimme, 2006), TPSSTPSS (Staroverov, 2003), M11 (Peverati and Truhlar, 2011), wB97 (Rajchel, 2010), wB97X (Zhao and Truhlar, 2008), wB97XD (Iikura, 2001), M05-2x (Zhao et al., 2006), M06 (Zhao and Truhlar, 2008), M06-L (Chakraborty, 2006), M06-2X (Walker, 2013) and N12-NX (Peverati and Truhlar, 2012). For all strategies, frequency calculation was performed as usual to ensure that all structures are minima in the potential energy surface and also to extract the zero-point energy (ZPE). Gaussian 09 programs package (Gaussian09, 2009) was performed to perform all computations.

The AEA without/with zero-point energies (ZPE) is calculated according to the following equations.

3 Results and discussion

The zero-point energies and the total electronic energies of the investigated benzaldehyde derivatives are summarized in Tables S1-S6 of the supplementary materials. The AEAs values without zero-point energy as calculated by using all the suggested computational methods are available from authors upon request. Several statistical descriptors (see supplementary materials) were computed to validate the accuracy of the examined computational strategies in reference to the experimental values (Mallard and Linstrom, 2012).

3.1 Analysis of composite high level ab initio and hybrid DFT methods

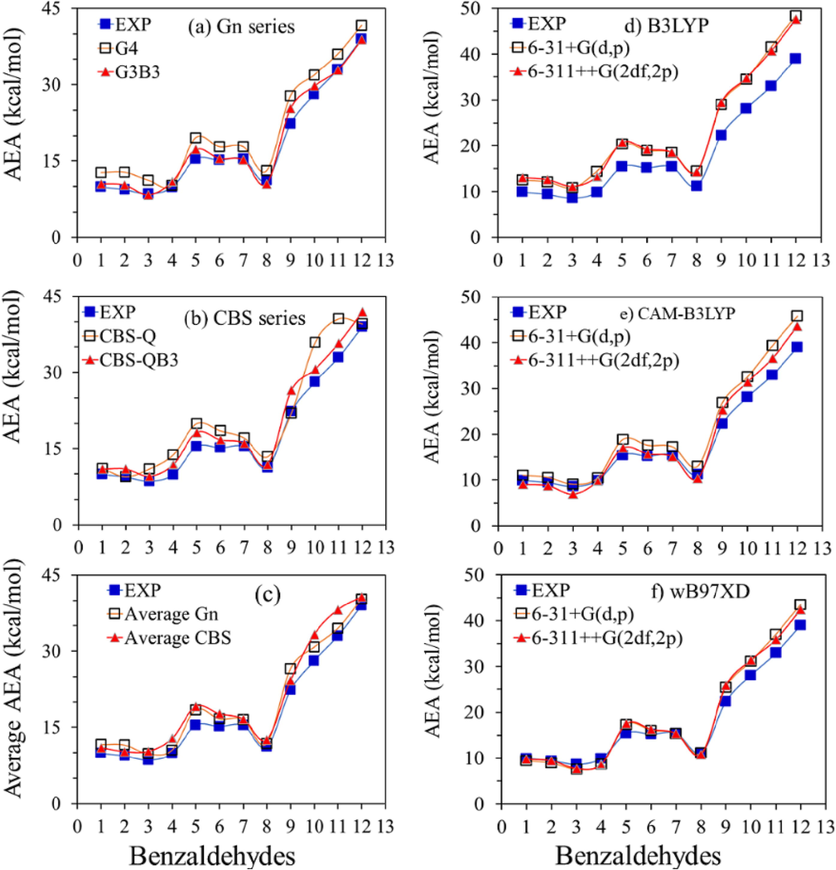

The twelve AEAs values of the investigated species as calculated using the suggested computational methods and the corresponding experimental results (Mallard and Linstrom, 2012) are summarized in Table 1.The distributions of these values are also shown in Fig. 2(a-c). In comparison with the experimental data, adequate agreements of the AEA values calculated using Gn and CBS methods can be clearly observed (Fig. 2(a and b)). Additionally, the distributions of the combined AEA values of Gn (G4 and G3B3) and CBS (CBS-Q and CBS-QB3) series are also shown in Fig. 2c, which show excellent consistencies with the experimental results.

EXPT (Mallard and Linstrom, 2012).

Gn

CBS

B3LYP

CAM-B3LYP

wB97XD

Av1a

Av2b

G4

G3B3

CBS-Q

CBS-QB3

BS1

BS2

BS1

BS2

BS1

BS2

H

10.12

12.72

10.53

11.05

10.94

12.49

13.01

10.99

9.05

9.41

9.74

10.74

9.40

3-CH3

9.41

12.8

10.27

9.428

10.97

12.1

12.57

10.52

8.76

8.93

9.41

10.62

9.09

4-CH3

8.60

11.21

8.361

10.98

9.54

10.79

11.11

9.04

6.93

7.55

7.7

8.95

7.32

3-OCH3

9.89

10.16

10.91

13.76

11.82

14.4

13.25

10.46

9.8

8.66

8.65

11.37

9.23

3-Cl

15.40

19.58

17.25

19.95

18.21

20.38

20.69

18.88

17.01

17.33

17.53

17.73

17.27

4-Cl

15.20

17.78

15.48

18.53

16.74

18.92

19.22

17.57

15.68

16.04

16.25

16.11

15.97

3-F

15.40

17.78

15.19

17.11

16.07

18.5

18.53

17.23

15.07

15.39

15.33

15.63

15.20

4-F

11.21

13.08

10.52

13.36

11.78

14.44

14.28

12.99

10.34

11.14

10.82

11.15

10.58

3-CN

23.33

27.78

25.29

21.96

26.45

29.01

29.4

26.89

25.26

25.41

25.81

25.87

25.54

4-CN

28.16

31.89

29.71

35.87

30.63

34.51

34.77

32.55

31.37

31.17

31.42

30.17

31.40

3-NO2

32.98

36.01

32.86

40.5

35.71

41.56

40.72

39.42

36.65

37.02

35.86

34.29

36.26

4-NO2

39.00

41.62

38.85

39.52

41.87

48.34

47.57

45.78

43.63

43.49

42.41

40.36

43.02

average

18.14

21.03

18.77

21.00

20.06

22.95

22.93

21.03

19.13

19.30

19.24

19.41

19.19

The 12 AEAs distributions as obtained by (a) Gn methods (b) CBS methods, (c) the averages of Gn and CBS methods, (d) B3LYP (e) CAM-B3LYP and (f) wB97XD methods. In all panels, available experimental AEA values are shown by filled blue circles (Mallard and Linstrom, 2012). All values are in kcal/mol.

The data presented in Table 1 demonstrate that the average AEA of G4 method are significantly higher than that of G3B3 method by 2.27 kcal/mol, which agrees with the previous studies (Yang, 2021). Whereas, the average AEA of CBS-Q method are higher than that of CBS-QBS method by 0.94 kcal/mol. The average AEA values of G4, G3B3, CBS-Q and CBS-QB3 methods are higher than that of the experimental value by 2.81, 0.55, 2.78 and 1.84 kcal/mol, respectively.

The AEAs calculated using the three hybrid DFT approaches: B3LYP, CAM-B3LYP and wB97XD, in combination with the 6–31 + G(d,p) and 6–311++G(2df,2p) basis sets are also presented in Table 1 and their distributions are also depicted in Fig. 2(d-e), together with the experimental results. Generally, very good matching is observed between the experimental EA values and the AEA as calculated by using the DFT approaches.

For 6–31 + G(d,p) basis set, the average value of AEA as calculated by using B3LYP and CAM-B3LYP approaches are 3.66 and 1.73 kcal/mol, respectively, much higher than that calculated by wB97XD approach. Interestingly, for 6–311++G(2df,2p) basis sets, the difference between the average AEA value calculated by B3LYP approach is 3.68 kcal/mol much higher than wB97XD approach, while the average AEA value in the case of CAM-B3LYP functional becomes almost equal to that of wB97XD functional.

The results show that the average AEAs as calculated by using wB97XD approach with 6–31 + G(d,p) and 6–311++(2df,2p) basis sets are highly matching the experimental results with a difference of 1.07 and 1.02 kcal/mol. For B3LYP approach, the average AEA value is ∼ 4.7 kcal/mol higher than that of the experimental AEA value, regardless of the elected basis sets. For the CAM-B3LYP functional, the average AEA values obtained by using 6–31 + G(d,p) and 6–311++(2df,2p) bases sets are 2.81 and 0.91 kcal/mol, respectively, higher than the experimental results data.

However, G3B3 and CBS-QB3 methods as well as the wB97XD and CAM-B3LYP approaches in combination with 6–311++G(2df,2p) basis set can compute very good AEA values, but they require a very long CPU time and they are not advisable to compute the AEA for larger compounds. Unfortunately, optimization of the large chemical compounds using the 6–311++G(2df,2p) basis sets is computationally cost compared to 6–31 + G(d,p) basis set. So that, it is very important to find an alternative pathway to compute accurate AEA values with low CPU time. B3LYP method is, in the mixed functional, relatively simple, and geometrical calculations speed is fast, and it has low dependence on the integration grid point. However, B3LYP has succeeded in many applications, such as geometrical structure (Safi and Wazzan, 2021; Safi et al., 2022; Barbas, 2020; Yang, 2022), but unfortunately, it has been failed in the computation of the ionization potential and electron affinity, which it only computes 70–75% of the actual values (Safi et al., 2022). It was suggested that B3LYP could be modified by remote mixing density functionals like wB97X or wB97XD (Stephens et al., 2008; Mardirossian and Head-Gordon, 2014), which is fast and low CPU time-consuming. Alternatively, to achieve accurate AEAs value with low computation cost, single point calculation using fifteen different DFT approaches in combination with the 6–311++G(2df,2p) bases set at the B3LYP/6–31 + G(d,p) geometries of both neutral and its radical anions is used. The results obtained are summarized in Table 2. Inspection of Table 2 shows that the average AEA calculated by the BMK, wb97, wb97X and wb97XD are the closest ones to the experimental results. It is found that the average AEA values of the mentioned DFT approaches are higher than the experimental values by 1.11, 1.16, 1.28 and 1.46 kcal/mol. Whereas, the poorest results are reported by B3LYP, B3PW91 and B97D. The average AEA value calculated by approaches are much higher than that of the experimental value by 4.89, 4.88 and 4.53 kcal/mol, respectively. 1: wb97, 2: wB97X, 3: wB97XD, 4: B3LYP, 5, B3PW91, 6: B97D, 7: BMK, 8: M11, 9: M05-2X, 10: M06, 11: M06-2X, 12: M06-L, 13: N12-SX, 14: TPSSTPSS, 15: CAM-B3LYP. *ΔAEA = AEAcalc-EAexp.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

H

9.84

9.89

9.96

12.92

13.11

12.71

8.85

11.86

11.44

12.23

10.88

10.36

10.36

12.26

11.63

3-CH3

9.55

9.57

9.59

12.67

12.79

12.46

8.56

11.54

11.24

12.17

10.77

9.99

9.99

12.11

11.31

4-CH3

7.90

7.94

8.03

11.21

11.39

11.25

6.93

10.04

9.46

10.75

9.06

8.69

8.69

10.94

9.69

3-OCH3

12.01

11.92

11.79

14.79

14.91

14.61

10.81

14.08

13.56

14.51

13.02

12.42

12.42

14.28

13.61

3-Cl

17.41

17.57

17.68

20.73

20.78

20.32

17.15

19.71

19.44

19.84

18.76

18.00

18.00

20.11

19.40

4-Cl

16.20

16.37

16.45

19.29

19.33

18.83

15.64

18.47

17.89

18.40

17.29

16.41

16.41

18.60

18.10

3-F

15.84

15.69

15.54

18.57

18.50

17.85

14.56

18.03

17.56

17.69

16.57

15.42

15.42

17.64

17.50

4-F

11.21

11.13

11.05

14.29

14.12

13.84

9.79

13.52

12.76

13.17

11.81

10.78

10.78

13.52

13.03

3-CN

25.23

25.45

25.89

29.49

29.93

29.78

25.52

27.60

27.73

29.03

26.67

27.77

27.77

29.35

27.57

4-CN

31.11

31.29

31.65

34.90

35.37

34.83

31.26

33.44

33.70

34.39

32.69

33.19

33.19

34.50

33.21

3-NO2

35.05

35.43

35.97

40.79

40.01

40.00

38.02

37.71

38.74

39.79

37.07

38.00

38.00

40.02

38.67

4-NO2

41.19

41.74

42.60

47.62

46.98

46.54

44.93

44.09

45.66

46.48

44.07

44.87

44.87

46.62

45.18

average

19.38

19.50

19.68

23.11

23.10

22.75

19.34

21.67

21.60

22.37

20.72

20.49

20.49

22.50

21.58

ΔAEA*

1.16

1.28

1.46

4.89

4.88

4.53

1.11

3.45

3.38

4.15

2.50

2.27

2.27

4.28

3.35

Furthermore, correlation of the different computational methods examined here shows a linear relationships correlation with R2 very close to unity (Figure S1 of the supplementary materials). For example, the results of AEAs of CBS-QB3, CAM-B3LYP/6–311++G(2df,2p) and wB97XD/6–311++G(2df,2p) are linearly correlated with those of G3B3 with R2 = 0.9978, 0.9965 and 0.9972, respectively. Additionally, the average AEA values of G3B3 and CBS-QB3 are also linearly correlated with those of the combination of CAM-B3LYP and wB97XD with 6–311++G(2df,2p) with R2 = 0.9983.

3.2 Statistical analysis

The accuracy of the different computational methods, which were applied to calculate the AEAs of the twelve benzaldehyde derivatives can be well examined by computing several statistical descriptors such as MAX, MAD, MD and RMSE. Full details about these statistical descriptors and the equations than can be used to calculate them are given in the supplementary materials. The most relevant statistical descriptors are displayed in Table 3. The graphical representation of RMSE values is shown in Fig. 3. Furthermore, possible linear correlations between the calculated AEAs using the different computational methods and the experimental ones are also examined. The values of R2, slopes, and intercepts of all the expected correlation are also gathered in Table 3. In all cases, excellent linear correlations between the 12 AEAs calculated by the different computational methods and the experimental ones are obtained with R2 very close to unity (See Figure S2 of supplementary materials).

MAX

MAD

MD

RMSE

R2

Slope

intercept

Gn series

G3B3

2.99

0.87

0.63

1.21

0.989

0.980

−0.330

G4

5.48

2.90

2.90

3.15

0.987

0.950

−1.850

CBS seies

CBS-QB3

4.15

1.93

1.93

2.20

0.994

0.930

−0.500

CBS-Q

7.76

2.92

2.87

3.85

0.949

0.880

−0.280

Full optimization using hybrid DFT

wB97X (BS2)

3.51

1.59

1.13

2.07

0.860

1.530

0.860

CAM-B3LYP (BS2)

4.63

1.76

1.01

2.27

0.830

2.190

0.830

wB97XD (BS1)

4.49

1.73

1.18

2.29

0.840

1.960

0.840

CAM-B3LYP (BS1)

6.78

2.91

2.91

3.60

0.830

0.770

0.830

B3LYP (BS2)

8.57

4.81

4.81

5.23

0.830

−0.920

0.830

B3LYP (BS1)

9.35

4.84

4.84

5.36

0.810

−0.560

0.810

DFT/6–311++G(2df,2p)//B3LYP/6–31 + G(d,p) approach

wb97

3.00

1.41

1.24

1.76

0.993

0.913

0.436

wb97x

3.18

1.53

1.37

1.92

0.994

0.900

0.594

wb97xd

3.60

1.70

1.55

2.20

0.993

0.878

0.851

BMK

5.93

2.21

1.20

2.78

0.995

0.802

2.633

M06-2x

5.07

2.59

2.59

3.06

0.993

0.872

0.070

M06-L

5.87

2.43

2.36

3.30

0.990

0.822

1.288

N12-SX

6.72

2.48

2.46

3.41

0.995

0.811

1.425

M11

5.33

3.54

3.54

3.80

0.994

0.895

−1.255

Cam-B3LYP

6.19

3.44

3.44

3.84

0.995

0.861

−0.430

M05-2x

6.66

3.46

3.46

3.96

0.995

0.845

−0.118

M06

7.48

4.24

4.24

4.69

0.993

0.841

−0.672

TPSSTPSS

7.63

4.36

4.36

4.82

0.993

0.837

−0.701

B97D

7.54

4.61

4.61

5.02

0.992

0.845

−1.086

B3PW91

7.99

4.97

4.97

5.34

0.993

0.846

−1.414

B3LYP

8.62

4.97

4.97

5.38

0.995

0.834

−1.140

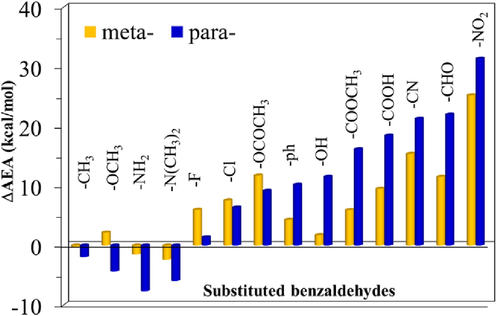

Graphical representation of the change in AEA of the m- and p-monosubstituted benzaldehyde with respect to the AEA of the parent benzaldehyde as computed using the wb97/6–311++G(2df,2p//B3LYP-6–31 + G(d,p) level of theory in the gas phase. All values are in kcal/mol.

For the first strategy, inspection of Table 3 and Figure S3 indicates that among the Gn and CBS series, the lowest RMSE values (the most accurate method) of 1.22 kcal/mol is found for the G3B3 method, whereas, the largest one (least accurate) is found for CBS-Q method. Therefore, the accuracy of the different Gn and CBS series can be arranged as follows: G3B3 > CBS-QB3 > G4 > CBS-Q.

For the second strategy, the data given in Table 3 and shown in Figure S3 suggest that the smallest RMSE (most accurate) is computed by wB97XD/6–311++G(2df,2p) level of theory, while the highest one (least accurate) is reported for B3LYP/6–11 + G(d,p) level of the theory. It is also found that the RMSE value reported for CAM-B3LYP/6–311++G(2df,2p) is slightly higher than that reported for wB97XD/6–311++G(2df,2p) by ∼ 0.20 kcal/mol. Based on the RMSE values, the accuracy of the three hybrid DFT approaches can be ranked as follows: wB97XD/6–311++G(2df,2p) > CAM-B3LYP/6–311++G(2df,2p) > wB97XD/6–31 + G(d,p) > CAM-B3LYP/6–31 + G(d,p) > B3LYP/6–311++G(2df,2p) > B3LYP/6–31 + G(d,p). The MAX values are 3.00, 3.18, and 3.60 kcal/mol, respectively. The results reveal that B3LYP approach is not a good choice to compute the AEAs, regardless of the basis set examined, while the wB97XD and CAM-B3LYP are good choices, especially with 6–311++G(2df,2p) basis set, and they able to compute AEA as accurate as the Gn and CBS series.

For DFT/6–311++G(2df,2p)//B3LYP/6–31 + G(d,p) approaches, based on RMSE values the wb97 is the most accurate approaches, while the B3PW91 and B3LYP are the least accurate ones. Indeed, the computed RMSE values for wb97, wb97x, and wb97XD approaches are 1.76, 1.92, and 2.20 kcal/mol, while those that are reported for B3LYP and B3PW91 approaches are 5.34 and 5.38 kcal/mol. Additionally, we find out that BMK, M06-2X, M06-L, and N12-SX methods give a moderate accuracy with RMSE values of 2.78, 3.06, 3.30, and 3.41 kcal/mol. Based on the data listed in Table 3 and shown in Figure S3, the fifteen DFT approaches can be ranked, according to their accuracy (from highest to lowest), as follows: wB97 > wB97X > wB97XD > BMK > M06-2X > M06-L > N12-SX > M11 > CAM-B3LYP > M05-2X > M06 > TPSSTPSS > B97D > B3PW91 > B3LYP. It is important to mention that, however the CPU time required to compute the AEA using the wb97 and wb97X with 6–311++G(2df,2p) at the B3LYP/6–31 + G(d,p) geometry is much shorter than that of the hybrid DFT with 6–311 + G(2df,2p) basis set, the accuracy of the AEA value computed by the former is higher than that of the later.

According to the above discussion, we can safely conclude that using the wB97 and/or wB97x with 6–311++G(2df,2p) basis at the B3LYP/6–31 + G(d,p) geometry able to reproduce AEA as accurate as those computed by G3B3, CBS-QB3 and they are a good choice in terms of CPU time and accuracy.

3.3 Prediction of the AEAs of some substituted benzaldehyde.

According to the results obtained the AEAs of seventeen monobenzaldehyde derivatives were calculated using the wb97, wb97X, and wB97XD with 6–311++G(2df,2p) bases set at the B3LYP/6–31+(d,p) geometry. The results are gathered in Table 4 and full set of data are collected in Table S6 of the supplementary materials. To our best knowledge, the AEAs of most of the chosen derivatives were not reported in the literature.

Species

Method

Average

wb97

wb97x

wb97XD

3-CHO

21.36

21.84

22.77

21.99

3-OH

11.58

11.46

11.27

11.44

3-COOH

19.36

19.64

20.33

19.78

3-COOCH3

15.78

15.98

16.50

16.09

3-NH2

8.32

8.20

8.00

8.17

3-N(CH3)2

7.63

7.47

7.23

7.45

3-ph

14.15

14.44

15.10

14.56

3-OCOCH3

21.60

21.51

21.43

21.51

4-CHO

31.80

32.16

32.82

32.26

4-OH

21.36

21.84

22.77

21.99

4-COOH

28.27

28.42

28.82

28.50

4-COOCH3

25.99

26.20

26.66

26.28

4-NH2

2.17

2.05

1.89

2.04

4-N(CH3)2

4.04

3.93

3.72

3.89

4-ph

20.03

20.16

20.73

20.31

4-OCH3

5.49

5.54

5.51

5.51

4- OCOCH3

19.01

18.98

18.95

18.98

The results obtained show that the predicted average AEA values of the examined derivatives vary from 7.45 to 32.26 kcal/mol and these values are well compared with those of the twelve known benzaldehydes, supporting the selected methodology.

3.4 Analysis of the substituent effect on the calculated AEA values.

The changes in the AEA values of the benzaldehyde derivatives as calculated by using the wB97/6–311++G(2df,2p)//B3LYP/6–31 + G(d,p) approach, due to the substitution of the different groups at m- and p-position (ΔAEA) is given by the following equation.

The ΔAEA is graphically shown in Fig. 3. It is indicated that substitution of electron-withdrawing groups (EWGs) increases AEA values, and the reverse is true in the case of electron-donating groups (EDG). Actually, the ΔAEA are negative in the case of EDGs, with the exception of m-OCH3, and they are positive for all EWGs, regardless of their position. It is found the AEAs of the p-NO2 and m-NO2 derivatives are the largest ones, with ΔAEA of 31.35 and 25.21 kcal/mol. Whereas, the p-NH2 and p-N(CH3)2 derivatives have the smallest AEAs values among all the investigated species. Interestingly, the results also show, except of -F, -Cl, and –OCOCH3 groups, that substitution of the EDGs and/or EWGs at the para position results in larger ΔAEA values compared to that at m-position (Fig. 3). It is also found that the AEA of m-F is 4.63 kcal/mol higher than that of the p-F derivative. Additionally, the substitution effect of –OH group at meta position is neglected compared to that at para position. Indeed, our results show that the AEA of m-OH derivative is 9.78 kcal/mol lower than that of the p-OH derivatives.

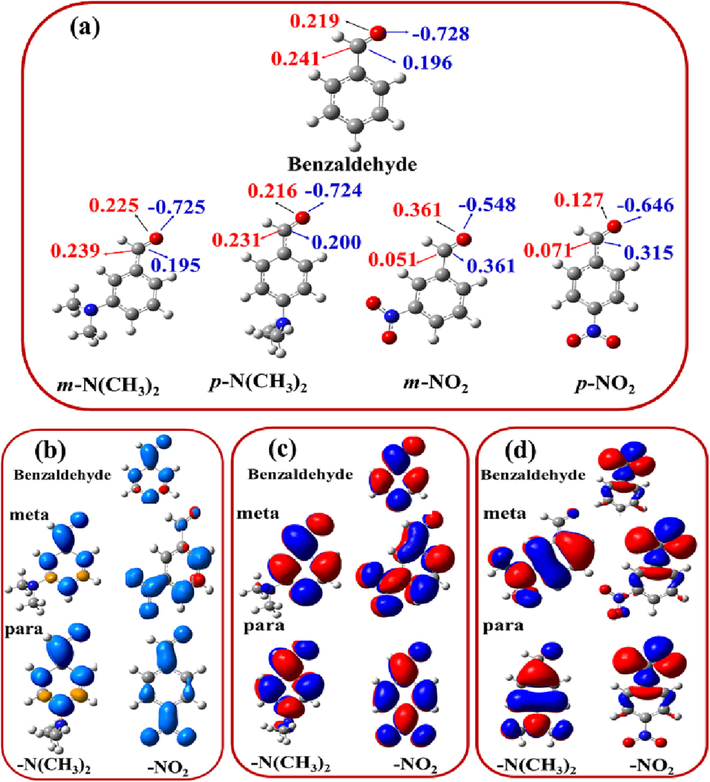

These results can be approved by considering the change in the natural spin densities and the natural charges. The natural charges and the corresponding natural spin densities were used to explain the changing pattern in the AEA of the m- and p-monosubstituted benzaldehyde at m- and p- position using the Natural Bond Orbital Analysis (NBO). The numerical values of the natural spin densities and the natural charges of m-NO2, p-NO2, m-N(CH3)2 and p-N(CH3)2 derivatives are shown in Fig. 4a. Whereas, the distribution of the spin densities and the singly occupied molecular orbitals (SOMO) for the anions for the same derivatives are also shown in Fig. 4 (b and c). For the sake of comparison, the electron distribution of the HOMO surfaces of the corresponding neutral species are also show in Fig. 4d.

(a) Natural charges and the natural spin densities of some m- and p-monosubstituted benzaldehydes anions (benzaldehyde, --N(CH3)2 and NO2). (Natural spin density in red and Natural charges in blue), (b) spin densities surfaces, (c) singly occupied molecular orbitals (SOMO) of radical anions and (d) highest occupied molecular orbital surfaces of the neutral species of some m- and p-monosubstituted benzaldehydes anions. The HOMO, SOMO, the natural spin densities, and the natural charges of the anions species are computed using the B3LYP/6–31 + G(d,p) level of theory.

It is well known that EWGs can decrease the electron density of a conjugated pi system, while the EDG can increase this conjugation. Additionally, EDGs can donate or release electrons and EWGs can withdraw electrons. In order to simplify our discussion, we will only follow the changes in the natural spin densities and natural charges of the carbon and atoms of the aldehyde group. It can be clearly observed that the substituent groups have different effects on the spin densities and the natural charges according to the type of the EDGs or EWGs and their replacing. For example, the substitution of NO2 group (EWG) decreases the natural spin densities of the C and O atoms. Whereas, a reverse effect is observed in the case of the natural charges. Importantly, and in consistence with the calculated AEAs, substitution of NO2 group at p- position has a higher effect than that at the meta position and the reverse effect is true in the case of the EDGs. That is to say, EWGs and/or EDGs decrease and/or increase the natural spin densities and increase and/or decrease the natural charges of the adjacent carbon atoms to the substitution position. The degree of the substitution effects greatly depends on the substitution position (meta or para). These effects can also be observed by monitoring the surfaces of the natural spin densities (Fig. 4b).

Monitoring of Fig. 4(b-d) shows that there are different effects on the natural atomic charges, natural spin densities of the adjacent carbon atoms to the substituted groups, as well as the carbonyl groups. It is also observed, upon anion formation, that the distribution of the electron densities of the SOMO, which occupies the incoming electrons, of the anions is completely different compared to the electron distribution of the HOMO of the corresponding neutral ones. Inspection of Fig. 4c shows that the SOMO is located on the whole moiety of the anions, indicating that the incoming electron is the delocalization of the incoming electrons.

3.5 Influence of attaching excess electrons on the geometrical structure

Significant structural changes have occurred in the geometrical structures (bond lengths and bond angles) in radical anions compared to the neutral species. The change in the geometrical structures of the bonds C1-C7 and C7 = O bond lengths and the angle C1-C7 = O for the neutral species and their radical anions at B3LYP/6–31 + G(d,p) are discussed. The most relevant geometrical structure parameters are listed in Table 5.

neutral

anion

C1-C7

C7 = O

C1-C7 = O

C1-C7

C7 = O

C1-C7 = O

H

1.481

1.219

124.9

1.428

1.271

126.7

3-CH3

1.480

1.219

125.0

1.429

1.269

126.8

3-NH2

1.481

1.218

125.1

1.429

1.271

126.8

3-OCH3

1.482

1.218

124.9

1.428

1.270

126.6

3-Cl

1.484

1.217

124.6

1.428

1.268

126.4

3-F

1.484

1.217

124.6

1.428

1.269

126.5

3-CN

1.486

1.216

124.3

1.435

1.258

126.2

3-NO2

1.486

1.216

124.2

1.461

1.233

126.2

3-CHO

1.484

1.217

124.5

1.451

1.244

127.3

3-OH

1.483

1.218

124.8

1.429

1.270

126.6

3-COOH

1.484

1.218

124.5

1.444

1.249

126.3

3-COOCH3

1.483

1.217

124.9

1.438

1.255

127.5

3-N(CH3)2

1.481

1.219

125.1

1.429

1.271

126.6

3-ph

1.481

1.218

124.9

1.440

1.255

126.4

3-OCOCH3

1.484

1.217

124.6

1.429

1.266

126.4

4-CH3

1.478

1.220

125.0

1.428

1.271

126.8

4-NH2

1.469

1.223

125.4

1.428

1.272

126.6

4-OCH3

1.473

1.221

125.2

1.428

1.270

126.6

4-Cl

1.480

1.218

124.7

1.428

1.268

126.5

4-F

1.479

1.219

124.8

1.428

1.272

126.4

4-CN

1.485

1.217

124.4

1.431

1.258

126.8

4-NO2

1.487

1.216

124.2

1.443

1.243

126.9

4-CHO

1.485

1.217

124.5

1.435

1.252

127.0

4-OH

1.474

1.221

125.1

1.428

1.273

126.5

4-COOH

1.485

1.217

124.6

1.434

1.254

127.0

4-COOCH3

1.484

1.218

124.7

1.433

1.255

127.0

4-N(CH3)2

1.466

1.224

125.5

1.428

1.269

126.7

4-ph

1.477

1.220

124.9

1.433

1.255

127.0

4- OCOCH3

1.481

1.218

124.7

1.428

1.267

126.4

average

1.481

1.218

124.8

1.433

1.262

126.7

Change

−0.048

0.044

1.9

Inspection of Table 5 shows that the bond C1-C7 is decremented, the bond C7 = O is incremented, and the angle C1-C7 = O is opened. The average decrement of bond C1-C7 is 0.048 Å and the average increment of bond C7 = O is 0.044 Å. The angle C1-C7 = O is opened by 1.9°. Upon anion formation, the decrement in the bond C1-C7 is changed from 0.025 to 0.056 Å, the increment in the bond C7 = O is ranged from 0.017 to 0.053 Å, and angle C1-C7 = O is opened is the range of 1.189 to 2.774°. The maximum decrement in the bond C1-C7 of 0.056 Å is reported for 3-F and 3-Cl derivatives, while the minimum decrement in the bond C1-C7 of 0.025 Å is reported for 3-NO2 derivatives. The maximum increment in the bond C7 = O of 0.054 Å is found for 4-F derivative and the lowest increment is found in the case of 3-NO2 derivative. For the angle C1-C7 = O, the minimum deviation of 1.2° is found for the 4-N(CH3)2 and 4-NH2 derivatives, while the maximum deviation of 2.5° is reported for 3-CHO derivative.

4 Conclusions

-

-

In the current study, the adiabatic electron affinities (AEAs) of the 12 m- and p-monosubstituted benzaldehyde were calculated using 4 different composite high-level ab methods (G3B3, G4, CBS-Q, and CBS-Q) and three hybrid DFT methods (B3LYP, CAM-B3LYP and wB97XD) with two bases sets (6–31 + G(d,p) and 6–311++G(2df,2p).

-

-

Among the high-level ab initio methods, the AEA calculated by G3B3 and CBS-QB3 methods are in excellent agreement with the experimental results, and they are good choices for computing the AEA, while the accuracy of the G4 and CBS-Q methods are lower than that of G3B3 and G4 and they are not good choices to calculate the AEA.

-

-

Using the hybrid wB97XD and CAM-B3LYP functional with the 6–311++G(2df,2p) are also a good choice computation model to compute the AEA, but the 6–311++G(2df,2p) is highly CPU cost, especially for a larger system.

-

-

The computation of the AEA by performing a single point calculation using the wB97, wB97X, and wB97XD functionals with 6–311++G(2df,2p) at the B3LYP/6–31 + G(d,p) geometry can be used as alternative and cheaper computational to compute accurate AEA values.

-

-

For the first time, the AEA of another 17 benzaldehyde derivatives were computed using the wB97, wB97X, and wB97XD functionals with 6–311++G(2df,2p) at the B3LYP/6–31 + G(d,p) geometry. The AEAs of these derivatives are reasonable in comparison with the AEA of the known derivatives.

-

-

All AEAs of the monosubstituted benzaldehyde derivatives are positive in the gas phase with all methods, indicating that all radical anions are stable with respect to electron attachment adiabatically and vertically in the gas phase.

-

-

Our results showed that when the substituent is EDG, the predicted AEA is smaller than that of the parent benzaldehyde, while for the EWG, the AEA is higher than that of the parent benzaldehyde. The greatest effect of EWG is observed in case of NO2 group in both positions, while the largest effect of the EDG is observed for p-NH2 derivative. In most case, substitution at para- position has a greater effect than that at meta- position. Moreover, for the EWG, the natural spin densities of the C and O of the aldehyde group are smaller than those in the unsubstituted benzaldehyde, while the reverse effect is true in case of EDGs.

-

-

The decrement of bond length of C1-C7 and the increment of bond length of C7 = O and the opening of the bong angle C1-C7 = O indicate that the structures of anionic states of monosubstituted benzaldehydes have larger changes when comparing with the neutral state.

Acknowledgments

Nuha Wazzan gratefully acknowledges the High-Performance Computing Centre (Aziz Supercomputer) at King Abdulaziz University (http://hpc.kau.edu.sa) for assisting with the calculations for this study.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Gaussian-3 theory using density functional geometries and zero-point energies. J. Chem. Phys.. 1999;110(16):7650-7657.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sildenafil–resorcinol cocrystal: XRPD structure and DFT calculations. Crystals. 2020;10(12):1126.

- [Google Scholar]

- Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys.. 1993;98:5648.

- [Google Scholar]

- Development of density functionals for thermochemical kinetics. J. Chem. Phys.. 2004;121(8):3405-3416.

- [Google Scholar]

- Combined valence bond-molecular mechanics potential-energy surface and direct dynamics study of rate constants and kinetic isotope effects for the H+ C 2 H 6 reaction. J. Chem. Phys.. 2006;124(4):044315

- [Google Scholar]

- Ab initio calculation of ionization potential and electron affinity of six common explosive compounds. Reports Theor. Chem.. 2012;1:11-19.

- [Google Scholar]

- Gaussian-4 theory using reduced order perturbation theory. J. Chem. Phys.. 2007;127(12):124105

- [Google Scholar]

- Gaussian09, R.A., 1, mj frisch, gw trucks, hb schlegel, ge scuseria, ma robb, jr cheeseman, g. Scalmani, v. Barone, b. Mennucci, ga petersson et al., gaussian. Inc., Wallingford CT, 2009. 121: p. 150-166.

- Semiempirical GGA-type density functional constructed with a long-range dispersion correction. J. Comput. Chem.. 2006;27(15):1787-1799.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ionization energies and electron affinities from a random-phase-approximation many-body Green's-function method including exchange interactions. Phys. Rev. A. 2017;95(6):062513

- [Google Scholar]

- Ab initio computation of electron affinities of substituted benzalacetophenones (chalcones): a new approach to substituent effects in organic electrochemistry. Electrochim. Acta. 2004;50(4):1039-1047.

- [Google Scholar]

- A long-range correction scheme for generalized-gradient-approximation exchange functionals. J. Chem. Phys.. 2001;115(8):3540-3544.

- [Google Scholar]

- Dehalogenation of 5-halouracils after low energy electron attachment: A density functional theory investigation. Chem. A Eur. J.. 2002;106(46):11248-11253.

- [Google Scholar]

- DFT study of ionization potentials and electron affinities of formamide and its methylation derivatives. Russ. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2011;85(8):1384-1389.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mallard, W. and P. Linstrom, National Institute of Standards and Technology (https://webbook.nist.gov): Gaithersburg, MD, 2012. There is no corresponding record for this reference.[Google Scholar].

- ωB97X-V: A 10-parameter, range-separated hybrid, generalized gradient approximation density functional with nonlocal correlation, designed by a survival-of-the-fittest strategy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys.. 2014;16(21):9904-9924.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry. Acc. Chem. Res.. 1985;18(10):316-322.

- [Google Scholar]

- Thermal Electron Attachment to Pyruvic Acid, Thermal Detachment from the Parent Anion, and the Electron Affinity of Pyruvic Acid. Chem. A Eur. J. 2022

- [Google Scholar]

- Low-energy electron capture in group 14 methyl chlorides and tetrachlorides: Electron transmission and dissociative electron attachment spectra and MS-Xα calculations. J. Chem. Phys.. 1998;108(21):9004-9015.

- [Google Scholar]

- A complete basis set model chemistry. VII. Use of the minimum population localization method. J. Chem. Phys.. 2000;112(15):6532-6542.

- [Google Scholar]

- Electron affinity and redox potential of tetrafluoro-p-benzoquinone: A theoretical study. J. Fluor. Chem.. 2008;129(3):222-225.

- [Google Scholar]

- A complete basis set model chemistry. V. Extensions to six or more heavy atoms. J. Chem. Phys.. 1996;104(7):2598-2619.

- [Google Scholar]

- Improving the accuracy of hybrid meta-GGA density functionals by range separation. J. Phys. Chem. Lett.. 2011;2(21):2810-2817.

- [Google Scholar]

- Screened-exchange density functionals with broad accuracy for chemistry and solid-state physics. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys.. 2012;14(47):16187-16191.

- [Google Scholar]

- Transforming anion instability into stability: contrasting photoionization of three protonation forms of the phosphate ion upon moving into water. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2012;116(44):13254-13264.

- [Google Scholar]

- A density functional theory approach to noncovalent interactions via interacting monomer densities. PCCP. 2010;12(44):14686-14692.

- [Google Scholar]

- Atomic and molecular electron affinities: photoelectron experiments and theoretical computations. Chem. Rev.. 2002;102(1):231-282.

- [Google Scholar]

- Proton affinity and molecular basicity of m-and p-substituted benzamides in gas phase and in solution: A theoretical study. Chem. Phys. Lett.. 2014;610:321-330.

- [Google Scholar]

- Benchmark calculations of proton affinity and gas-phase basicity using multilevel (G4 and G3B3), B3LYP and MP2 computational methods of para-substituted benzaldehyde compounds. J. Comput. Chem.. 2021;42(16):1106-1117.

- [Google Scholar]

- Calculation of vertical and adiabatic ionization potentials for some benzaldehydes using hybrid DFT, multilevel G3B3 and MP2 methods. Chem. Phys. Lett.. 2022;791:139349

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparative assessment of a new nonempirical density functional: Molecules and hydrogen-bonded complexes. J. Chem. Phys.. 2003;119(23):12129-12137.

- [Google Scholar]

- The determination of the absolute configurations of chiral molecules using vibrational circular dichroism (VCD) spectroscopy. Chirality: The Pharmacological, Biological, and Chemical Consequences of Molecular Asymmetry. 2008;20(5):643-663.

- [Google Scholar]

- The relative electron affinities of the α and β chains of oxyhaemoglobin as a function of pH and added inositol hexaphosphate: An electron spin resonance study. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Protein Structure. 1978;537(1):70-76.

- [Google Scholar]

- Performance of M06, M06–2X, and M06-HF density functionals for conformationally flexible anionic clusters: M06 functionals perform better than B3LYP for a model system with dispersion and ionic hydrogen-bonding interactions. Chem. A Eur. J.. 2013;117(47):12590-12600.

- [Google Scholar]

- A new hybrid exchange–correlation functional using the Coulomb-attenuating method (CAM-B3LYP) Chem. Phys. Lett.. 2004;393(1–3):51-57.

- [Google Scholar]

- Theoretical study on adiabatic electron affinity of fatty acids. New J. Chem.. 2021;45(36):16892-16905.

- [Google Scholar]

- A theoretical study on the proton affinity of sulfur ylides. New J. Chem.. 2022;46(17):7910-7921.

- [Google Scholar]

- The M06 suite of density functionals for main group thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, noncovalent interactions, excited states, and transition elements: two new functionals and systematic testing of four M06-class functionals and 12 other functionals. Theor. Chem. Acc.. 2008;120(1):215-241.

- [Google Scholar]

- Design of density functionals by combining the method of constraint satisfaction with parametrization for thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, and noncovalent interactions. J. Chem. Theory Comput.. 2006;2(2):364-382.

- [Google Scholar]

- Constant current linearization for determination of electron capture mechanisms. Anal. Chem.. 1983;55(9):1596-1599.

- [Google Scholar]

Appendix A

Supplementary material

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2023.102719.

Appendix A

Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article: