Translate this page into:

Genome-wide identification and analysis of GRF (growth-regulating factor) gene family in Camila sativa through in silico approaches

⁎Corresponding author. azkhan@ksu.edu.sa (Azmat Ali Khan)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Objective

GRFs (growth-regulating factors) are transcription factors that significantly influence plant development and stress response. In the present study, genome-wide discovery and analysis of the CsGRF family and its significant roles in Camelina sativa development was done utilizing model GRF genes of Arabidopsis thaliana that are available in the public domain databases.

Methods

Gene structure analysis, exon and intron structures, phylogenetic analysis, mapping of various GRF genes on the chromosome's distribution, conserved domain analysis, and synteny analysis will be systematically categorized. Investigation of cis-regulatory elements will also be carried out using various bioinformatic approaches.

Results

In the C. sativa genome, 19 GRF gene members and 4 GRF variants were found using publicly available genomic data. The encoding regions of GRF1, GRF2, GRF2A, and GRF8 were similar and maximal, i.e., 2046 bp, which encodes 555 amino acids, followed by GRF2. C. sativa has the most GRF gene representatives, scattered throughout six chromosomes, and appears to have 3 to 4 protein-coding regions. GRF is involved in biological processes (44.7%), molecular activities (50%), and cellular functions (24.6%). The molecular weights of GRF proteins range from 29.57 to 61.57 kDa. The majority of GRF proteins have a theoretical PI between 7.0 and 9.42. All CsGRFs have preserved QLQ and WRC (Trp, Arg, Cys) domains. All C. sativa proteins have SNH and QG (Gln, Gly) domains. The motif composition and gene structure of CsGRFs from the same sub-group were similar. In the analysis of conserved domains, the motifs of CsGRF genes were highly conserved. According to synteny investigations, large-scale duplications played a significant role in expanding the CsGRF family.

Conclusions

Our findings will help to understand the functions of the GRF family in the evolutionary and physiological aspects of C. sativa and provide a future direction for novel work to improve crop productivity. Identifying single-gene families in multiple plant species is best to enhance crop productivity, growth, and development.

Keywords

Genome-wide analysis

GRF genes

Growth-regulating factor

Arabidopsis thaliana

Camelina sativa

Protein domains

Phylogenetic analysis

1 Introduction

Transcriptional control is a biological mechanism that is related to certain gene areas and is being studied to drive differentiation, growth, development, and metabolism (Giguère, 2008; Shapira and Seale, 2019). The various actions of transcriptional factors have an impact on gene expression (Cook and Marenduzzo, 2018). An earlier study on Arabidopsis thaliana identified several distinct transcriptional factors; for example, 1500 and about 675 were investigated as plant-specific transcriptional factors (Krizek et al., 2020; Snyman, 2019). The growth-regulating factor (GRF) genes are found in the genomes of a variety of seed plants and are designed to regulate the plant's growth and development mechanisms (Huang et al., 2021; Li et al., 2021).

The GRF family proteins are encoded by plant-specific transcription factors, which have two conserved domains in the N terminal region: QLQ (Gln, Leu, Gln) and WRC (Trp, Arg, Cys) (Chen et al., 2019). The QLQ is identified in yeast with two distinct proteins designated SWI2/SNF2 and is associated with the yeast SWI/SNF complex epigenetic modifications (Xun et al., 2022). WRC (Trp, Arg, Cys) is a plant-specific domain with a C3H motif for DNA binding, as well as putative zing finger or proper nuclear localization signals (NLS), three Cys, and one His (Avci et al., 2016). The C-terminal part of GRFs is variable. Some studies have shown that the C-terminal region of GRFs has trans-activating activity and contains specific less conserved motifs, such as QTL and FFD (Omidbakhshfard et al., 2015; Xun et al., 2022). The GIF genes show a mechanism for calcium signaling pathways (Lau et al., 2019); related transcriptional coactivators, and conserved regions of DNA, such as SSXT and SNH (Zan et al., 2020).

The first GRF gene was identified in rice and Zea mays (Cao et al., 2016b). The GRF genes are encoded by 14–3–3 proteins, which are widely distributed in many eukaryotes and play a key role in the regulation of a variety of biological processes ranging from metabolism to transport, growth, development, and stress response, as well as mediating the shape and size of leaves by regulating cell proliferation (Liu et al., 2016). Moreover, GRFs also contribute to the development of floral parts to regulate the size of seeds and control flower expeditions (Omidbakhshfard et al., 2015). Some GRF genes suppress Knotted1-like Homeobox (KNOX) expression, which prevents cell differentiation in the shoot apical meristem (Jia et al., 2020; Kuijt et al., 2014).

Previous researchers (Cao et al., 2016a; Omidbakhshfard et al., 2015) demonstrated the significance of several GRFs in plant biology, which contain highly synthetic information. Despite this, no genome-wide investigation of the GRF gene family in A. thaliana has been performed. The miR396 microRNA, which appears to affect seven of the nine genes, reduces the activity and abundance of GRF transcripts via post-transcriptional regulation (Bazin et al., 2013; Hewezi and Baum, 2012). A. thaliana AtGRF7 usually functions as a regulator of osmotic stress-responsive genes, minimizing the deleterious impact of those genes on plant growth (Kim and Tsukaya, 2015). However, when under stress, its synthesis is reduced by activating osmotic stress-responsive genes.

The A. thaliana genome yielded nine GRF genes ATGRF1 (AT2G22840.1), ATGRF2 (AT4G37740.1), ATGRF3 (AT2G36400.1), ATGRF4 (AT3G52910.1), ATGRF5 (AT3G13960.1), ATGRF6 (AT2G06200.1), ATGRF7 (AT5G53660.1), ATGRF8 (AT4G24150.1), and ATGRF9 (AT2G45480.1) which were used to analyze gene families in false flax (Camelina sativa) and provide genetic resources for future research. We identified the GRF genes in C. sativa by utilizing all accessible genes and protein resources as per the methods used in earlier research (Rather and Dhandare, 2019; Zafar et al., 2021). Multiple bioinformatics approaches were used to identify and examine cis-regulatory elements, including gene structure analysis, exon and intron structures, phylogenetic analysis, mapping of various GRF genes on the chromosome distribution, conserved domain analysis, and synteny analysis.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Datasets

The materials for A. thaliana GRF genes were obtained from Plant TFDB (https://planttfdb.gao-lab.org), a plant transcriptional factor database. The various variants, as listed in Supplementary Table 1, were chosen and utilized as a query sequence for C. sativa genes. To evaluate the cis-regulatory elements, the promoter sequence of 1 kilobyte (Kb) upstream of the start codon was downloaded from the Phytozome genome database (https://www.phytozome.net). A BLASTN search was performed from the NCBI database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) to search for candidate genes of C. sativa by using default eating parameters like 10 expectation values, 11 world size, and 25 maximum score numbers in a single line. The cDNAs were retrieved as predicted genes if their e-value meets the set criteria of E ≤ e-10. Further, BLAST searches were also carried out utilizing potential GRF genes as a sequence in the NCBI protein database. The conserved domain was subsequently identified with the use of a local database and the BLASTp program. GRF protein sequences from new plant species that matched C. sativa were identified as GRF genes using the BLASTp program and then mapped on individual chromosomes.

2.2 Gene structure, conserved motifs, and phylogenetic analysis of GRF genes

The TAIR (https://www.arabidopsis.org) database, which is available online, was used for gene analysis. It was used to extract and visualize the organization of exons, introns, and UTRs for individual GRF genes (Rhee et al., 2003). For a schematic depiction of the gene, a gene structure map was created using an online suite called Gene Structure Display Server (http://gsds.gao-lab.org) (Guo et al., 2007). MEME, a sequence analysis program that provides motif-based sequence analysis and is freely available online (https://meme-suite.org), was used to identify protein-conserved motifs (Bailey et al., 2015). The minimum and maximum motif widths were set to 5 and 50, repetition of any number with a distribution of zero or one occurrence per sequence, and all-out motifs were set to 10. To determine evolutionary relationships among GRF genes, the Clustal X version 2.0 (Larkin et al., 2007), with default settings, was used for multiple sequence alignment of the full-length amino acid sequence of GRF proteins from A. thaliana. The neighbor-joining method was adopted with 1000 bootstrap replicates as per the earlier invitation to find relations (Zafar et al., 2020). This method helped construct an unrooted phylogenetic tree using MEGA (molecular evolution genetic analysis) software (Kumar et al., 1994). The evolutionary distances between nine members of the GRF gene family were calculated using this method. The tree was then further presented in circular form among a group of closely related sequences using Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) v4 (Letunic and Bork, 2019).

2.3 Gene portrayal and interpretation of GRF structure

The exon-intron structure analysis was performed using the Gene Structure Display Server 2.0 (http://gsds.gao-lab.org/) independent research tool which assists in distinguishing gene structure and comparing it to orthologs in the monocot, dicot, and A. thaliana genomes. The simple modular architecture research tool (SMART) (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/) was used to predict and validate the conserved domains based on sequence homology.

2.4 Proteomic analysis of GRF gene family

The protein size, molecular weight (MW), and theoretical isoelectric point (pI) of each GRF protein were measured using the Expy proteomics Server (https://www.expasy.org), proteome database, and sequence analysis tools. Multiple Expectations-Maximization for Motif Elicitation 5.05 (MEME) was utilized to identify protein sequence motifs. The MEME is a collection of numerous ways of discovering and scanning motifs. The MEME motifs found were then looked for using the ScanProsite server (https://prosite.expasy.org/scanprosite/) in the ExPASyProsite database (https://www.expasy.org).

2.5 Protein-protein and DNA-protein interaction and subcellular localization of GRF protein

Protein-protein interaction and subcellular localization of a few GRF proteins from large datasets of GRF proteins were performed by using the String database (https://string-db.org). GRF's DNA-protein interaction was performed by using the accessible online HDOCK web server (http://hdock.phys.hust.edu.cn). A subcellular position of the GRF1 protein was discovered by using the CELLO2GO tool (http://cello.life.nctu.edu.tw/cello2go/).

2.6 Chromosome mapping of GRF genes

The positions of the individual tri-helix genes were retrieved from the corresponding database. All nine GRF genes were shown and mapped to their chromosomal locations on five A. thaliana chromosomes using the TAIR open-access database's chromosome map tool (https://www.arabidopsis.org/jsp/ChromosomeMap/tool.jsp).

2.7 Synteny analysis

To explore the sequence similarity patterns, Circoletto (https://tools.bat.infspire.org/circoletto/) was used to perform synteny analysis and visualize sequence identity among the GRF family genes (Darzentas, 2010).

2.8 Promoter analysis

We retrieved a 1 Kb nucleotide sequence upstream to the start codon for all nine genes using the Phytozome database (http://www.phytozome.net/). These were then subjected to the PLACE cis-regulatory elements database for the identification of already experimentally defined motifs (Higo et al., 1999). Five cis-regulatory elements were obtained, they were CACTFTPPCA1, CURECORECR, GATABOX, ARR1AT, and DOFCOREZM, and their conserved sequences were YCAP, GTAC, GATA, NGATT, and AAAG, respectively. Their locations were then mapped manually.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Identification and characterization of GRF genes in C. sativa

By using available genomic resources of A. thaliana (Supplementary Table 1), a total of 19 GRF genes includes GRF1(XM_010473979.2), GRF1A (XM_010430916.2), GRF2 (XM_010448327.2), GRF2A (XM_010433733.2), GRF3 (XM_010518559.1), GRF3A (XM_010511173.2), GRF3B ( XM_010506884.2), GRF4 (XM_010517467.2), GRF4A* (XM_010505740.2), GRF4B* (XM_010505738.1), GRF-5(XM_010488877.2), GRF5A (XM_010466969.2), GRF5B (XM_010503161.2), GRF6 (XM_010468817.2), GRF6A (XM_010414605.2), GRF7 (XM_010444638.2), GRF7A (XM_010447680.2), GRF7B (XM_010484472.2), GRF8 (XM_010440777.2), GRF8A (XM_010438107.2), GRF8B (XM_010450302.2), GRF9A* (XM_010519863.2), GRF9B* (XM_010519864.2) and 4 GRF variants GRF4A* (XM_010505740.2), GRF4B* (XM_010505738.1), GRF9A* (XM_010519863.2), GRF9B* (XM_010519864.2) have been identified in the C. sativa genome. The information about their corresponding genomic sequence, coding sequence, and several exons is summarized in Table 1. GRF1, GRF2, GRF2A, and GRF8 had identical and maximal coding areas, i.e. 2046 bp, which encodes 555 amino acids, followed by GRF2. Variants of GRF4 like (GRF4A*, GRF4B*, GRF9A* and GRF9B*) have five similar exons, GRF1, GRF1A, GRF2, GRF2A, GRF3, GRF3A, GRF3B, GRF4, GRF-5, GRF5A, GRF5B, GRF8, GRF8A, GRF8B also has four same exons on each gene, GRF6, GRF6A, GRF7, GRF7A, GRF7B have the same number of exons, i.e., 3. Genes GRF5B and GRF6A were located on identical chromosomes, i.e., 1, GRF3B, GRF4A*, GRF4B* i.e. 4, GRF3, GRF4, GRF9A* and GRF9B* i.e. 6, GRF7 and GRF8 i.e. 11 and GRF2 and GRF8B i.e. 12, GRF5A and GRF6, i.e., 15. The remaining genes (GRF1, GRF1A, GRF2A, GRF3A, GRF5, GRF7A, and GRF7B) were located on 16, 9, 10, 5, 19, 2, and at 18 individually.

Gene

AC

PS length

Genomic length

Chr#

CDS

Exon

Location

CS-GRF-1

XM_010473979.2

522 aa

2012

16

1583

4

(22853482..22856276)

CS-GRF1-A

XM_010430916.2

413 aa

1552

9

1242

4

(32848239..32850532)

CS-GRF-2

XM_010448327.2

555 aa

2046

12

1667

4

(1248377..1250937)

CS-GRF2-A

XM_010433733.2

553 aa

2041

10

1661

4

(1150346..1152941)

CS-GRF-3

XM_010518559.1

391 aa

1724

6

1175

4

(19718380..19721255)

CS-GRF-3-A

XM_010511173.2

389 aa

1651

5

1169

4

(6886016..6888847)

CS-GRF-3-B

XM_010506884.2

390 aa

1627

4

1172

4

(23506820..23509613)

CS GRF-4

XM_010517467.2

394 aa

1532

6

1184

4

(15438920..15441433)

CS GRF4-A*

XM_010505740.2

396 aa

1623

4

1190

5

(18785969..18789406)

CS GRF4-B*

XM_010505738.1

396 aa

1444

4

1190

5

18785969..18789406)

CS-GRF-5

XM_010488877.2

403 aa

1882

19

1211

4

(6640988..6643350)

CS-GRF-5-A

XM_010466969.2

409 aa

1850

15

1229

4

(6340433..6342759)

CS-GRF-5-B

XM_010503161.2

406 aa

1604

1

1220

4

(6033263..6035370)

CS-GRF-6

XM_010468817.2

253 aa

1097

15

761

3

(19656074..19657381)

CS-GRF-6-A

XM_010414605.2

295 aa

996

1

887

3

(19300713..19301918)

CS-GRF-7

XM_010444638.2

371 aa

1249

11

1115

3

(41644025..41645499)

CS-GRF-7-A

XM_010447680.2

362 aa

1544 bp

2

1088

3

(18245074..18246828)

CS-GRF-7-B

XM_010484472.2

364 aa

1233

18

1094

3

(13063356..13064817)

CS-GRF-8

XM_010440777.2

435 aa

2091

11

1307

4

(9340709..9343207)

CS-GRF-8-A

XM_010438107.2

407 aa

1457

10

1223

4

(7996954..7998843)

CS-GRF-8-B

XM_010450302.2

435 aa

1452

12

1307

4

(9166277..9168099)

CS GRF9_A*

XM_010519863.2

439 aa

1745

6

1319

5

(25031829..25034249)

CS GRF9_B*

XM_010519864.2

437 aa

1735

6

1313

5

(25031829..25034249)

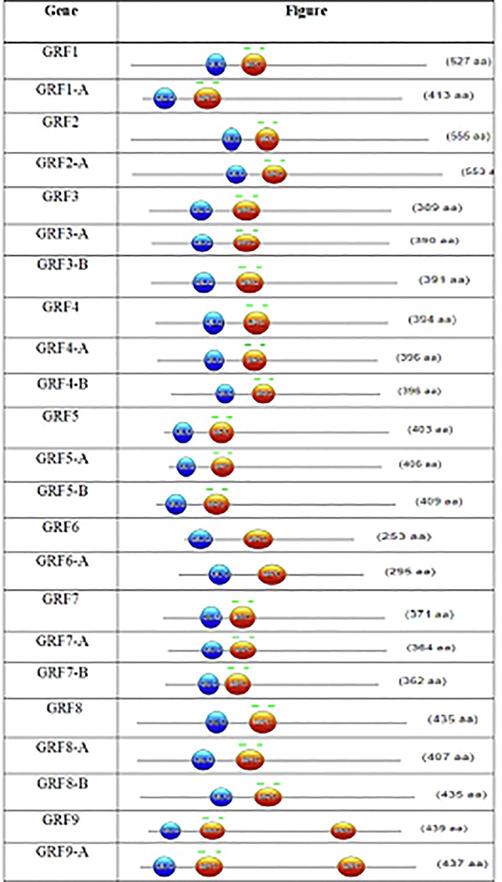

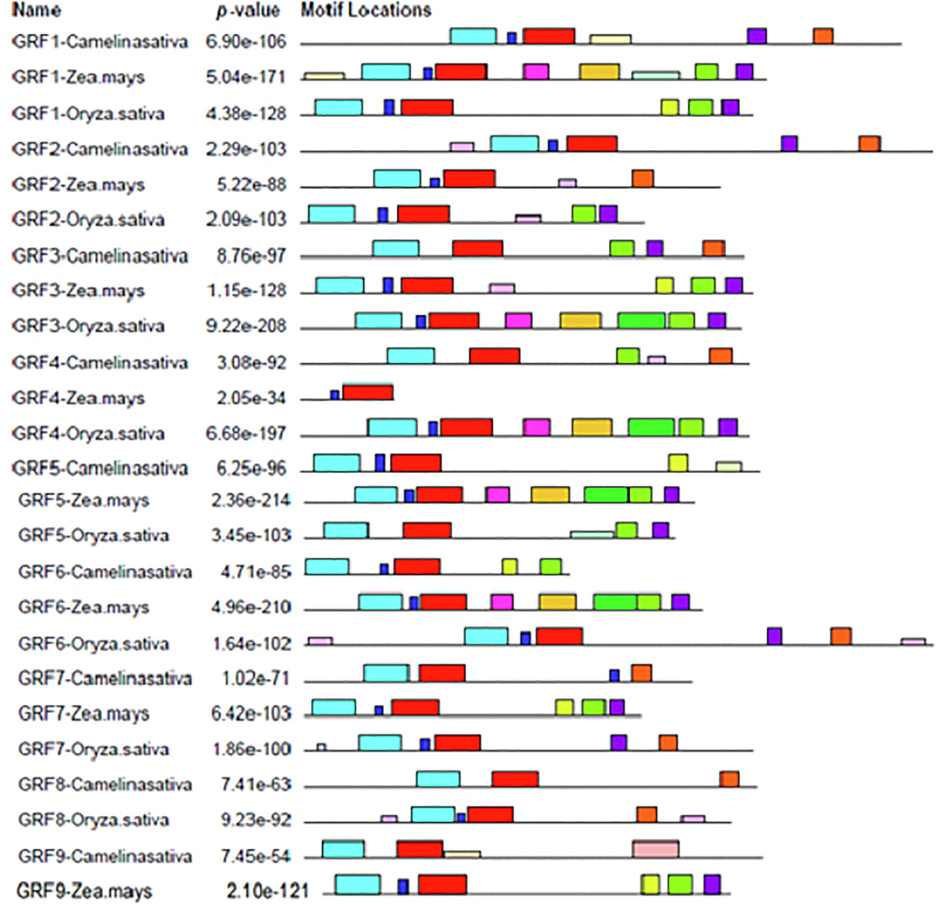

The number of introns/exons in C. sativa's 19 GRF genes varies, indicating that GRF genes differ amongst different types of plants. Nevertheless, the most closely related GRF genes, either in their exon lengths or intron numbers, displayed identical exon–intron arrangement and motif composition in the same subfamily. In addition, based on the MEME study, various conserved protein motifs were found in individual GRF proteins (Cao et al., 2016b). The variations among the sub-families in these characteristics showed that the members of the GRF were functionally diversified. Interestingly, all known GRF proteins have motif one and motif two that encode a conserved WRC domain. As seen in Fig. 1, in WRC motifs, zinc-finger structures are closely related, suggesting that this domain functions in DNA binding. The maximum length of the GRF gene in the present study is 2046 bp, with an open reading frame (ORF) encoding 555 amino acids as related to an earlier study of Gnetum luofuense (Hou et al., 2021). The total size of GRF1 in A. thaliana is 1583 bp, which encodes 552 amine acids (Liu et al., 2009). The GRF gene family has been examined in a range of plant species, but no plant orthologs for C. sativa's GRF, GRF4B*, GRF9A*, GRF9B*, or GRF10 genes have been observed. The variability of both exon-intron architectures and motif components of GRF genes could explain the functional differences of GRFs among the plant species investigated.

Schematic diagram of the conserved QLQ and WRC domains of all members of GRF gene family.

3.2 Comparative genome studies of GRF proteins

In the present study, by searching local genome databases, 1 to 9 GRF genes were identified in C. sativa, Oryza sativa, Malus domestica, Zea mays, Carica papaya, Arachis hypogaea, Glycine max, Rosa chinensis, Helianthus annuus, Brassica rapa, Ananas comosua, Capsella rubella, Cicer arietinum, Populus trichocarpa, Ipomoea triloba, Nicotiana tabacum, Spinacia oleracea, Brassica oleracea, Solanum tuberosum, and Coffea arabica. The comparative analysis of GRF genes of C. sativa with other plant species is summarized in Supplementary Table 2. According to comparative genome studies, while the chromosome numbers and genome sizes of different plant species varied, gene ordering within related species remained remarkably conserved across millions of years of evolution (Hardigan et al., 2020; Van de Velde et al., 2016). GRF gene family GRF1 to GRF10 has been already reported in various plant species (Cao et al., 2016a; Ma et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2014). In C. sativa, variants of GRF4 like (GRF4A*, GRF4B*, GRF9A*, and GRF9B*) have five similar exons; however, in the case of Chinese pear (Pyrus bretschneider), poplar (Populous), grape (Vitis vinifera), A. thaliana and rice (Oryza sativa) these all have same 5 number of exons (Cao et al., 2016). The GRF1, GRF1A, GRF2, GRF2A, GRF3, GRF3A, GRF3B, GRF4, GRF-5, GRF5A, GRF5B, GRF8, GRF8A, GRF8B also has four same exons on each gene, in the similar range as the four exons noted for all other plant species (Fonini et al., 2020; Ma et al., 2017; Shang et al., 2018). GRF6, GRF6A, GRF7, GRF7A, and GRF7B have three exons per the exact identification of earlier researchers (Cao et al., 2007; Ma et al., 2017). GRF2 genes encode 555 amino acids with four exons in their gene in the present work. The earlier researcher (Kim, 2019) reported plant-specific duplication of GRF, i.e., GRF2a and GRF2b, which have 555 and 553 amino acids with four exons.

3.3 Physiochemical properties of GRF proteins

To understand the biological functioning of GRF protein, we investigated their characteristics, including the molecular mass, theoretical pI, potential N-glycosylation sites, and functional domains. The molecular weight of GRF proteins ranged from 29.57 to 61.57 kDa (Table 2). The theoretical pI of most GRF proteins ranged between 7.0 and 9.42. In the C. sativa GRF proteins, the number of possible N-glycosylation sites ranged from one to six (Table 2). Figs. 1 and 2 show how the functional domains and motifs of studied GRF proteins were predicted using their protein sequences. As shown in Fig. 1, all GRF proteins have QLQ and WRC domains. Another feature of this domain is the absolute conservation of bulky aromatics or hydrophobic and acidic amino acid residues or their equivalents in chemical and radial properties. The Pro's residue is also fully conserved.

Gene

Molecular weight

Weight in kilo Dalton

PI

Formula

GRAVY

total number of atoms

N-Glycosylation sites

GRF1

56376.23

56.38 kDa

9.13

C2431H3790N724O792S17

−0.661

7754

6

GRF1-A

44200.94

44.21 kDa

9.42

C1911H2984N570O615S13

−0.650

6093

6

GRF2

61111.44

61.74 kDa

9.1

C2643H4108N782O858S17

−0.790

8408

6

GRF2-A

60753.93

61.32 kDa

9.1

C2621H4081N775O860S17

−0.807

8354

5

GRF3

42607.04

42.61 kD

8.26

C1843H2828N552O586S16

−0.701

5825

5

GRF3-A

42848.28

43.41 kDa

8.26

C1851H2836N552O587S16

−0.722

5842

4

GRF3-B

42727.19

43.29 kDa

8.25

C1853H2843N555O590S16

−0.702

5857

3

GRF4

44001.12

44.01 kDa

6.93

C1890H2879N579O611S16

−0.906

5975

1

GRF4-A

44004.22

44.01 kDa

6.93

C1894H2884N580O607S16

−0.860

5981

1

GRF4-B

44004.22

44.64 kDa

6.93

C1894H2884N580O607S16

−0.860

5981

3

GRF5

45525.52

45.54 kDa

7.8

C1954H2968N598O640S14

−1.068

6174

6

GRF5-A

46367.42

46.38 kDa

7.5

C1975H2997N605O641S14

−1.060

6232

3

GRF5-B

45921.03

45.93 kDa

7.81

C1993H3011N617O644S14

−1.089

6279

1

GRF6

29017.55

29.57 kDa

8.7

C1267H1967N365O393S13

−0.864

4005

2

GRF6-A

33858.12

34.41 kDa

8.99

C1489H2312N420O457S14

−0.706

4692

1

GRF7

41036.02

41.59 kDa

7.14

C1788H2810N502O572S17

−0.585

5689

1

GRF7-A

39852.79

39.86 kDa

7.66

C1741H2749N495O554S20

−0.555

5559

1

GRF7-B

40120.16

40.13 kDa

8.12

C1728H2724N490O553S20

−0.590

5515

5

GRF8

47718.71

47.73 kDa

9.11

C2059H3186N618O661S17

−0.708

6541

4

GRF8-A

44627.38

44.64 kDa

9.12

C1930H2990N570O621S16

−0.657

6127

2

GRF8-B

47686.64

47.70 kDa

8.73

C2057H3174N616O661S18

−0.670

6526

1

GRF9

49546.8

49.55 kDa

8.95

C2126H3425N643O678S22

−0.697

6894

1

GRF9-A

49376.59

49.38 kDa

8.95

C2118H3411N641O676S22

−0.714

6868

3

Motifs of GRF Genes: Motifs are indicated with conserved regions of amino acid and their different colors code their range.

For the QLQ domain's role, these amino acid residues, are essential probably for protein–protein interaction. The WRC domain has two peculiar structural properties: many essential amino acids (Arg and Lys) and the motif of C3H, which is the preserved spacing of three Cys and one residue of His and can mediate DNA binding (Zhang and Ghosh, 2001). The essential amino acids are highly conserved, suggesting that they are necessary for the WRC domain function, perhaps as a nuclear localization signal. The present finding is consistent with previous studies indicating that GRF's QLQ and WRC domains are strongly preserved (Cao et al., 2016b; Kim et al., 2003; Wu et al., 2014; Zan et al., 2020).

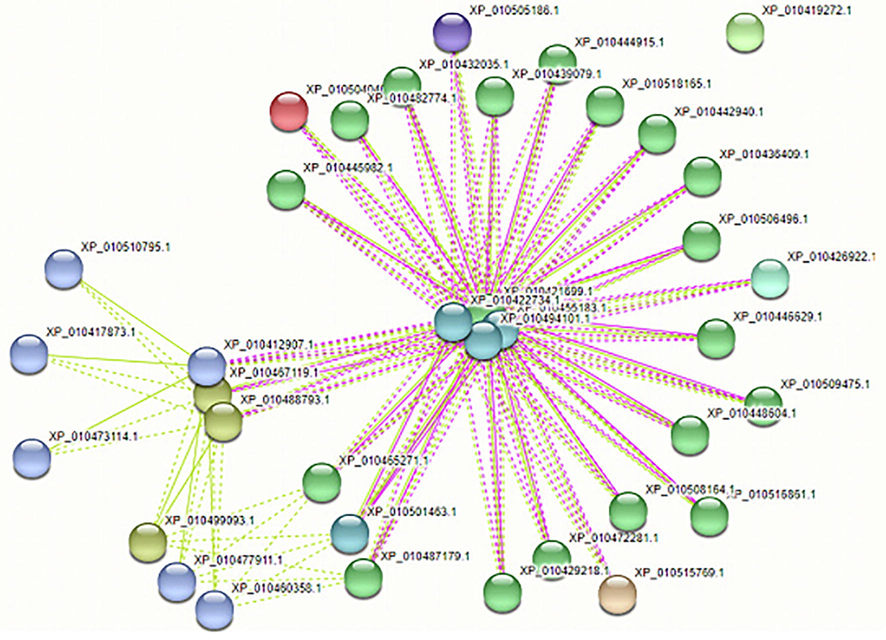

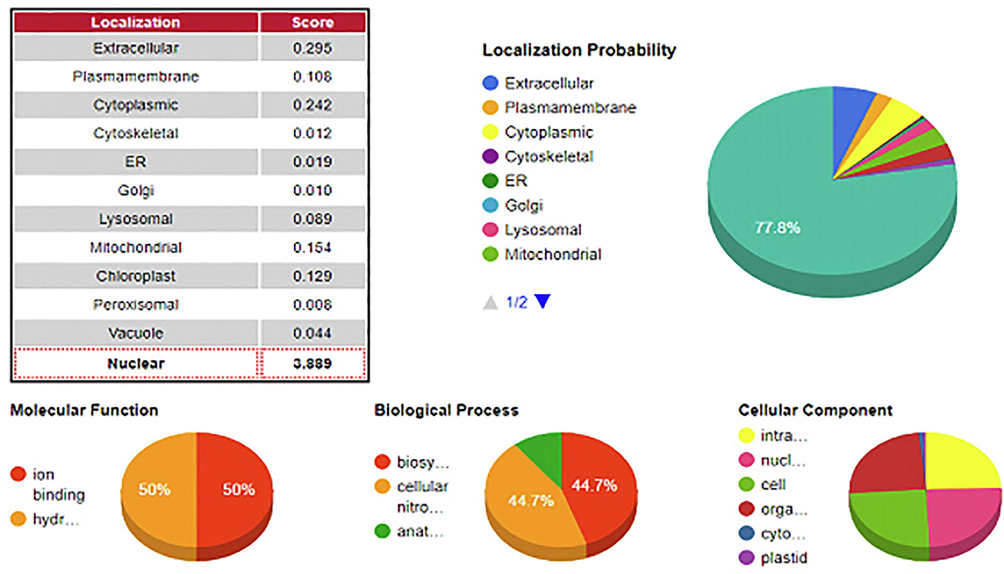

3.4 Protein-protein and DNA-Protein interaction and subcellular localization of GRF proteins

The network of all GRF families was downloaded from the String database. The networks were divided into clusters of different colors, as shown in Fig. 3. Having 37 nodes, the number of edges is 131, the average number of nodes is 7.08, the average local cluster coefficient is 0, and the expected number of rims is 11. To study in a better way, the interaction network was divided into 9 clusters by using the K-mean cluster. The cluster was composed of closely connected protein interactions, and the balls provided unspecified effects in the interaction network. The arrows show a positive action effect and the one that shows adverse effects. Proteins like the GRF family, Putative leucine-rich repeat receptor-like serine/threonine-protein kinase At2g14440, BEL1-like homeodomain protein five, etc. are presented in Supplementary Fig. 1. The localization probability revealed that GRF1 is mostly localized at the cell's nuclear region with a score of 3.889. As given in Fig. 4, GRF is involved in 44.7% biological functions, 50% molecular functions, and 24.6% cellular functions.

All GRF proteins interaction (Protein-protein interaction) with other proteins.

A localization probability of GRF1 in Camelina sativa.

Protein-protein interaction has shown that GRF interacts with other transcription factors such as GRF family proteins, At2g14440 serine/threonine-protein kinase, BEL1-like homeodomain protein 5, etc. These two proteins are directly or indirectly involved in plant reactions to abiotic stresses, including salt stress (Hewezi et al., 2012; Kim et al., 2012). The presence of a QLQ domain for protein–protein interactions, a WRC domain for DNA binding, and a potential nuclear localization signal characterize these proteins. All GRF modules, from 1 to 10, play an essential role in angiosperm growth and development. It determines the ultimate size and form of the leaf organ by regulating the meristematic potential of primordial cells during leaf development. The GRF pair is a pre-requisite for the production of floral organs. In mature leaves, it is also involved in controlling leaf survival and photosynthetic quality. Significantly, the monocot GRF duo also promoted the yield characteristics that guarantee crop productivity, such as grain size and panicle architecture. The GRF gene has a charophyte origin study of GRFs in the most primitive land plants, and charophytes might give information on their significance in an essential lineage of life's evolutionary developmental history (Kim, 2019).

3.5 Phylogenetic analysis of GRF genes

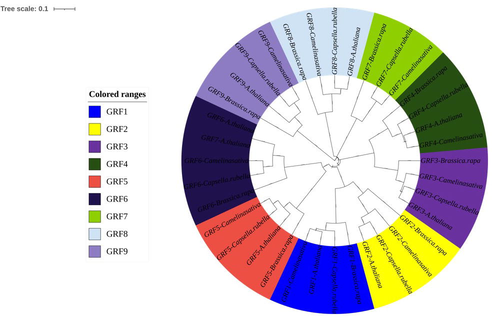

Phylogenetic research was used to accurately explain the evolutionary history of the GRF gene family in plant species. The GRF genes were grouped into five classes according to phylogenetic tree topology. As illustrated in Fig. 5, a phylogenetic examination of C. sativa with other species revealed that all of Camelina sativa's GRF genes were clustered with their homologs. It means that the GRF gene family as a whole is well conserved. GRF genes from C. sativa and other plants have been divided into clades. C. sativa, shown in Fig. 5, is related to Capcella rubella and A. thaliana (Cao et al., 2016). Orthologous pairs of pears and grape GRF proteins were more common, demonstrating that some ancestor GRF genes existed before pear and grape divergence occurred during evolution.

Phylogenetic tree analysis of GRFs from Camelina sativa with other species. The various colors represent the different GRF genes.

3.6 Chromosomal mapping of GRF genes

With the use of data from the public database NCBI, all GRF genes were physically mapped on the chromosomes of O. sativa (GCA_001433935.1) and Z. mays (GCA_902167145.1). C. sativa's (GCA_000633955.1) chromosome 6 has the highest number of GRF genes (3) of all the chromosomes, while the remaining linking chromosome has one of each GRF gene. The pattern of GRF gene distribution on chromosomes also identified distinct physical locations with a higher concentration of GRF genes (Supplementary Fig. 2). The chromosomal analysis found that all GRF genes present in various linkage groups with a maximum linkage group 3 were present in the current sample. The mapping of 9 C. sativa chromosome GRF genes with two other species of O. sativa and Z. mays at chromosome 4, is equivalent to a recent study (FİLİZ et al., 2014). A related GRF gene cluster type ranging from 1 to 9 was found in C. sativa.

3.7 Synteny analysis

The synteny analysis was done using Circoletto. It performed a local alignment and provided a circular output with colorful arcs (Fig. 6). Different colors represent the additional extension of similarity; blue shows the lowest similarity. The increasing likeness to a growing bit score of C. sativa with A. thaliana is shown in green, orange, and red. The majority of genes are orthologs; AT2G22840 and AT4G37740 are orthologs, while CS2G36400 and AT5G53660 are orthologs due to gene duplication. Microsynteny has been found in the studied twenty monocot and dicot plant genomes.

The synteny relationship among all the 9 genes of the GRF family generated using Circoletto. The variation of colors represent the extent of similarity and homology among the genes of Camelina sativa. The red color represents the maximum matching portion among the GRF family of Arabidopsis thaliana with Camelina sativa GRF genes.

3.8 Promoter analysis

Cis-acting regulatory DNA elements are promoter sequence control and expression regulatory elements. On a 1 Kb promoter sequence, five elements were chosen and mapped upstream of the start codons. CACTFTPPCA1, CURECORECR, GATABOX, ARR1AT, and DOFCOREZM were identified as cis-regulatory elements, and their conserved sequences were YCAP, GTAC, GATA, NGATT, and AAAG, respectively. CURECORECR is absent in Cs2G45480 and Cs3G13960, and this cis-regulatory element is present in the smallest proportion in all CsGRF genes. DOFCOREZM is found in large amounts in all CsGRF genes (Supplementary Table 3).

4 Conclusion

We identified 19 members of the GRF gene and 4 GRF variants, including their physical position, phylogenetic relationship, retained microsynteny, and a diversified set of C. sativa GRF genes. The QLQ and WRC domains are found in all GRF proteins. Results discovered that gene structure and motif distribution characteristics were generally maintained across subfamilies. A systematic study of GRF genes revealed a wide variety of synteny and the existence of one or more large-scale genome duplications during early evolution. Our observations indicate that the primary expansion trend for the vast majority of GRF genes was large-scale gene replication. Systematic research could help extrapolate the function of the GRF gene from one lineage to the next. The data will aid in a better understanding of the structural and functional features of the GRF gene family in plant species.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the researchers supporting project number (RSP-2021/339), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The work was done with the support of the Virtual University of Pakistan, Department of Bioinformatics (VUPDB) Lahore, Pakistan. The authors are also thankful to NCBI, ENSEMBLE, and other genomic biological databases and software for providing genomic resources in the public domain.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests.

References

- Order-wide in silico comparative analysis and identification of growth-regulating factor proteins in Malpighiales. Turkish Journal of Biology. 2016;40(1):26-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- miR396 affects mycorrhization and root meristem activity in the legume M edicago truncatula. Plant J.. 2013;74(6):920-934.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phosphate differentially regulates 14-3-3 family members and GRF9 plays a role in Pi-starvation induced responses. Planta. 2007;226(5):1219-1230.

- [Google Scholar]

- Regulations on growth and development in tomato cotyledon, flower and fruit via destruction of miR396 with short tandem target mimic. Plant Sci.. 2016;247:1-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparative genomic analysis of the GRF genes in Chinese pear (Pyrus bretschneideri Rehd), poplar (Populous), grape (Vitis vinifera), Arabidopsis and rice (Oryza sativa) Front. Plant Sci.. 2016;7:1750.

- [Google Scholar]

- Genome-wide identification of GRF transcription factors in soybean and expression analysis of GmGRF family under shade stress. BMC Plant Biol.. 2019;19(1)

- [Google Scholar]

- Transcription-driven genome organization: a model for chromosome structure and the regulation of gene expression tested through simulations. Nucleic Acids Res.. 2018;46(19):9895-9906.

- [Google Scholar]

- Circoletto: visualizing sequence similarity with Circos. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(20):2620-2621.

- [Google Scholar]

- Genome-wide identification and analysis of growth regulating factor genes in Brachypodium distachyon: in silico approaches. Turkish J Biol. 2014;38:296-306.

- [Google Scholar]

- Molecular evolution and diversification of the GRF transcription factor family. Genetics Mol Biol. 2020;43(3):20200080.

- [Google Scholar]

- Transcriptional control of energy homeostasis by the estrogen-related receptors. Endocr. Rev.. 2008;29(6):677-696.

- [Google Scholar]

- Genome synteny has been conserved among the octoploid progenitors of cultivated strawberry over millions of years of evolution. Front. Plant Sci.. 2020;10

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Complex feedback regulations govern the expression of miRNA396 and its GRF target genes. Plant Signaling Behav.. 2012;7(7):749-751.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Arabidopsis microRNA396-GRF1/GRF3 regulatory module acts as a developmental regulator in the reprogramming of root cells during cyst nematode infection. Plant Physiol.. 2012;159(1):321-335.

- [Google Scholar]

- Plant cis-acting regulatory DNA elements (PLACE) database: 1999. Nucleic Acids Res.. 1999;27(1):297-300.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparative analyses of full-length transcriptomes reveal Gnetum luofuense stem developmental dynamics. Front. Genet.. 2021;12

- [Google Scholar]

- Genome-wide analysis of growth-regulating factors (GRFs) in Triticum aestivum. PeerJ. 2021;9:e10701.

- [Google Scholar]

- Genome-wide identification of the MdKNOX gene family and characterization of its transcriptional regulation in Malus domestica. Front. Plant Sci.. 2020;11

- [Google Scholar]

- Analysis of GRF & plantar foot pressure of stepping foot on skilled & unskilled player's in the soccer instep shoot. Korean J. Sport Biomech.. 2012;22(1):17-24.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biological roles and an evolutionary sketch of the GRF-GIF transcriptional complex in plants. BMB Rep.. 2019;52(4):227-238.

- [Google Scholar]

- The AtGRF family of putative transcription factors is involved in leaf and cotyledon growth in Arabidopsis. Plant J.. 2003;36(1):94-104.

- [Google Scholar]

- Regulation of plant growth and development by the GROWTH-REGULATING FACTOR and GRF-INTERACTING FACTOR duo. J. Exp. Bot.. 2015;66(20):6093-6107.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Arabidopsis transcription factor AINTEGUMENTA orchestrates patterning genes and auxin signaling in the establishment of floral growth and form. Plant J.. 2020;103(2):752-768.

- [Google Scholar]

- Kuijt, S. J., Greco, R., Agalou, A., Shao, J., ‘t Hoen, C. C., Övernäs, E., et al. (2014). Interaction between the growth-regulating factor and knotted1-like homeobox families of transcription factors. Plant Physiol., 164(4), 1952-1966.

- MEGA: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis software for microcomputers. Bioinformatics. 1994;10(2):189-191.

- [Google Scholar]

- Activation of hedgehog signaling promotes development of mouse and human enteric neural crest cells, based on single-cell transcriptome analyses. Gastroenterology. 2019;157(6):1556-1571.

- [Google Scholar]

- Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) v4: recent updates and new developments. Nucleic Acids Res.. 2019;47(W1):W256-W259.

- [Google Scholar]

- Genome-wide identification and characterization of the abiotic-stress-responsive GRF gene family in diploid woodland strawberry (Fragaria vesca) Plants. 2021;10(9):1916.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ectopic expression of miR396 suppresses GRF target gene expression and alters leaf growth in Arabidopsis. Physiol. Plant.. 2009;136(2):223-236.

- [Google Scholar]

- 14-3-3 proteins: macro-regulators with great potential for improving abiotic stress tolerance in plants. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2016;477(1):9-13.

- [Google Scholar]

- Genome-wide analysis and expression profiling of the GRF gene family in oilseed rape (Brassica napus L.) Gene. 2017;620:36-45.

- [Google Scholar]

- Growth-regulating factors (GRFs): a small transcription factor family with important functions in plant biology. Mol. Plant. 2015;8(7):998-1010.

- [Google Scholar]

- Genome-Wide identification of doublesex and Mab-3-Related transcription factor (DMRT) genes in nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) Biotechnol. Rep,. 2019;24:e00398

- [Google Scholar]

- The Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR): a model organism database providing a centralized, curated gateway to Arabidopsis biology, research materials and community. Nucleic Acids Res.. 2003;31(1):224-228.

- [Google Scholar]

- Genome-wide analysis of the GRF family reveals their involvement in abiotic stress response in cassava. Genes. 2018;9(2):110.

- [Google Scholar]

- Transcriptional control of brown and beige fat development and function. Obesity. 2019;27(1):13-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Modulation of the Vitis vinifera cv. ‘Chardonnay’microRNA and mRNA Transcriptomes in Response to Aster Yellows Phytoplasma-infection. Stellenbosch: Stellenbosch University; 2019.

- A collection of conserved noncoding sequences to study gene regulation in flowering plants. Plant Physiol.. 2016;171(4):2586-2598.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Genome-wide identification and analysis of the growth-regulating factor family in Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa L. ssp. pekinensis) BMC Genomics. 2014;15(1):1-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Overexpression of the maize GRF10, an endogenous truncated growth-regulating factor protein, leads to reduction in leaf size and plant height. J. Integr. Plant Biol.. 2014;56(11):1053-1063.

- [Google Scholar]

- Xun, Q., Mei, M., Song, Y., Rong, C., Liu, J., Zhong, T., et al. (2022). SWI2/SNF2 Chromatin Remodeling ATPases SPLAYED and BRAHMA Control Embryo Development in Rice.

- Genome wide identification, phylogeny, and synteny analysis of sox gene family in common carp (Cyprinus carpio) Biotechnol. Rep,. 2021;30:e00607.

- [Google Scholar]

- Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of PPOs and POX gene families in the selected plant species. Biosci. Biotechnol. Res. Asia. 2020;17(2):301-318.

- [Google Scholar]

- Genome-wide identification and analysis of the growth-regulating factor (GRF) gene family and GRF-interacting factor family in Triticum aestivum L. Biochem. Genet.. 2020;58(5):705-724.

- [Google Scholar]

- Toll-like receptor–mediated NF-κB activation: a phylogenetically conserved paradigm in innate immunity. J. Clin. Investig.. 2001;107(1):13-19.

- [Google Scholar]

Appendix A

Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2022.102038.

Appendix A

Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article: