Translate this page into:

Evaluation of antiplasmodial potential of Beta vulgaris juice in Plasmodium berghei infected mice

⁎Corresponding authors at: Department of Biological Sciences, College of Science, King Faisal University, Al-Ahsa, Saudi Arabia (R.S. Yehia). rabdelgaber.c@ksu.edu.sa (Rewaida Abdel-Gaber), ryehia@kfu.edu.sa (Ramy S. Yehia)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

The parasite, Plasmodium sp. is responsible for Malaria, which kills around half a million people annually and its management relies on efforts of cooperation between health care personnel and the public sector. The effect of Beta vulgaris fresh juice on mice infected by the chloroquine-sensitive Plasmodium berghei berghei through in vivo trials was studied in King Fahad Medical Research Center, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. The EDs were estimated for the fresh juice activity and the secondary screening. There were significant differences in the parasitemia level (p = 0.0) between the negative control group and mice treated by B. vulgaris fresh juice and Chloroquine. The mean parasitemia level in infected untreated mice or B. vulgaris fresh juice was significantly differentiated at concentrations ranging from 10% − 80% (p = 0.0). ED50 and ED90 B. vulgaris fresh juice are estimated to be 24.5 (17.8–33.8) and 40.7 (24–68.8) at 5% confidence limits. This is optimistic and stimulates additional investigation on B. vulgaris fresh juice in vitro trials and further extraction of the active components of B. vulgaris against malaria.

Keywords

Plasmodium berghei

Beta vulgaris

Chloroquine

Herbal medicine

Antimalaria

1 Introduction

Malaria is one of the first illnesses and its references were cited in Chinese about 2700 BCE, in Egyptian papyri from 1570 BCE, and over 2500 BCE Hindu scriptures. The term malaria comes from Italian malaria, which meaning spoiled air, however, it is well known that this is doubtful (Francis, 2010). Plasmodium sp. parasite infects the vertebrate’s erythrocytes and constitutes a medical disaster that might increase rapidly, leading to complications and death without prompt and appropriate therapy (Larry and John, 2009). Malaria is responsible for the deaths of over a million people each year and about three billion are at risk of getting malaria infection by Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax (Hay et al., 2010).

Malaria diagnosis involves the identification of malaria parasite or its antigens or patient blood products (Chotivanich et al., 2006), while malaria control includes the man capable of transmitting the disease far and wide, the Plasmodium which can hide in humans and mosquitoes, and the Anopheles mosquito very well adaptable and resistant to insecticides (Shiff et al., 2011). Traditional herbal remedies against malaria are utilized for thousands of years. Some of the plants found have systematically definite antimalarial effects, their active components have been identified and their potential methods of action have been studied (Adebayo and Krettli, 2011).

Beetroot or garden beet is recognized in plants with red or purple tuberous root vegetables (Pavoković et al., 2009). Romans were the first to get concerned with the root of Beta vulgaris, used for their medicinal properties (Stephen, 2004). Beta vulgaris, which grows once a year and has tuberous rootstocks, is recognized as beetroot. It lives in the Mediterranean region and is extensively cultivated in Europe, America, and India (Escribano et al., 1998). B. vulgaris is used for several remediation functions in traditional treatment; its roots are expectorant, diuretic, and also as a medicine for cerebral disturbance, liver, and renal disorders, stimulating the immune and hematopoietic systems, as well as exacting diet in cancer healing (Kapadia et al., 1996; Kapadia et al., 2003).

This study aims to examine the effect of Beta vulgaris fresh juice on mice inoculated with Plasmodium berghei in primary screening (four-day suppressive test) and stable infection (curative test). Furthermore, estimate the values of effective doses ED50 and ED90 of the plant juice.

2 Material and methods

2.1 Preparation of Beta vulgaris juice

Fresh beetroots of small size were purchased from a local market and washed thoroughly with water to eliminate undesirable dirt. The herbarium specialist confirmed the identification of the plant. The beetroot was cut with a sharp knife and the juice was extracted by using the machine. The juice was freshly made for each experiment (Czapski et al., 2009).

2.2 Experimental procedure

Male Swiss albino mice (6–8 weeks old with 19–25 g) were used in this experiment. The animals were obtained from the Experimental Animal Unit in King Fahad Medical Research Center, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Under specified pathogen-free conditions, the mice were maintained in care plastic cages which have been modified with covers and fed to the normal diet and water ad libitum. Institutional review board approval and Ethical approval for this study were obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, King Abdulaziz University (Reference No. 657–19) for animal study.

2.3 Malaria parasites strain

The Chloroquine-sensitive Plasmodium berghei “ANKA Strain” was ordered from the Institute of Immunology and Infection Research in the European Malaria Reagent Repository, Edinburgh. The Plasmodium strain shipment amounted to 0.4 ml, it was stored carefully in 13.5 kg of dry ice, then promptly received and saved directly in liquid nitrogen at the BioBank, King Fahad Medical Research Center in King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Parasites were maintained by incessant re-infestation in mice (Christian et al., 2014).

2.4 Parasites inoculation

According to the Reece Lab Protocols from The European Malaria Reagent Repository, the experimental mice were inoculated by the intraperitoneal injection route with 0.2 ml suspension of 1 × 106 parasitized erythrocytes P. berghei ANKA strain (Boampong et al., 2013). In the infected donor mouse, parasitemia was identified by the procedure of stained tail blood smear (Wunderlich et al., 1982). The complete blood count (CBC) of the infected donor mouse was done in the EDTA tube utilizing an automated hematology analyzer and micro-sampling technology (Mindray BC-2800) for the blood samples taken from the orbital plexus.

2.5 Antimalarial activities

Before performing the antimalarial activities, inoculation of Plasmodium berghei “ANKA Strain” was done. Three screening steps of primary, secondary and tertiary screening were followed by integrated laboratory screening for antimalarial tests (David et al., 2004).

2.5.1 Primary screening

A 4-day suppressive screening with 27 mice, which were passed intraperitoneally with criterion inoculation of P. berghei including 106 infected erythrocytes in 8.967 ml PBS with 47% parasitemia level and the CBC was 2.9 (106/µl). Three hours later and randomly, the infected mice were divided into 3 groups (9 mice/group). For four consecutive days (from Day 0 through Day 3), mice were treated orally with 0.2 ml dose of the tested materials. Mice were classified into groups as:

Group 1: infected mice were administered only doses from distilled water (negative control)

Group 2: infected mice have received only a dose of 4 ml of B. vulgarius fresh juice with 8 ml distilled water equal to 30%

Group 3: infected mice were administered 5 mg/kg of Chloroquine (positive control)

On the fourth day, thin blood films were taken from mice tails. For all mice, the mean of parasitemia was expected to estimate the suppression % of malaria infection using the following formula (Sumsakul et al., 2014):

2.5.2 Secondary screening

The standard 4-day suppressive test was performed with 35 mice for effective doses (EDs) estimations. Mice were inoculated intraperitoneally with standard inoculation of P. berghei containing 106 infected erythrocytes in PBS with a level of 71% parasitemia and CBC as 1.5 (106/µl). The infected mice were administered orally by 0.2 ml of B. vulgaris fresh juice at varied doses and were randomly divided into 3 groups, as follows:

Group 1: infected mice that only administrated distilled water (negative control)

Group 2: infected mice have received individually 10–80% ml of B. vulgarius fresh juice, 5 mice for each concentration

Group 3: infected mice were administered 5 mg/kg of Chloroquine (positive control)

2.5.3 Tertiary screening

Best inhibitory concentrations of B. vulgaris fresh juice were studied in the Curative Test. This phase was done using 27 mice. On the first day of this test (Day 0), experimental animals were weighed and injected intraperitoneally with inoculums of 106 P. berghei infected erythrocytes in PBS with parasitemia level (56%) and CBC was 1.78 (106/µl). On Day 3 and according to the parasitemia level confirmation, mice were split into 3 groups (9 mice/group), as follows:

Group 1: infected mice were orally taken distilled water only (negative control)

Group 2: infected mice were orally received 5 mg/kg Chloroquine (positive control)

Group 3: infected mice were orally treated by the best suppressive concentration of B. vulgarius fresh juice

For each tested substance, the disease therapy lasted for 5 consecutive days with just one dosage each day. Blood smears were obtained and microscopically investigated for each mouse in all groups at the end of the study period to assess parasitemia level.

2.6 Statistical analysis

Data were statistically analyzed using a statistical package program (SPSS version 19.0). All values are expressed as the mean ± standard deviations (SD). Comparisons between treated and control groups were done by t-test, One-way ANOVA with Post Hoc test, and Two-way ANOVA. p ≤ 0.05 is considered as significant for all statistical analyses. Effective doses estimation was followed by Leitchfield and Wilcoxon (1949) to estimate the median effective dose, the slope of dose-percent effect curves, and to specify confidence limits of parameters with 5% probability. For drawing graphs, Sigmaplot program was utilized.

3 Results

3.1 Primary screening

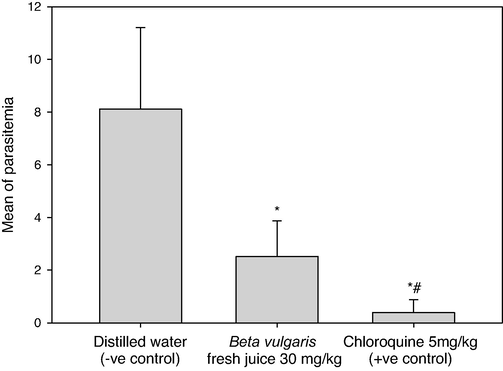

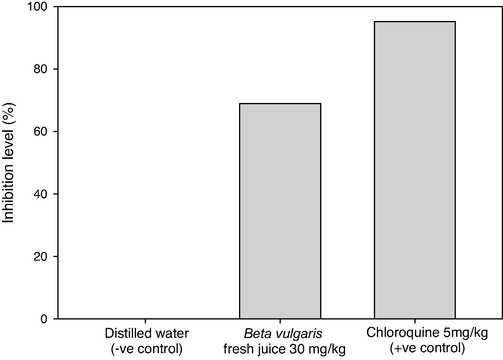

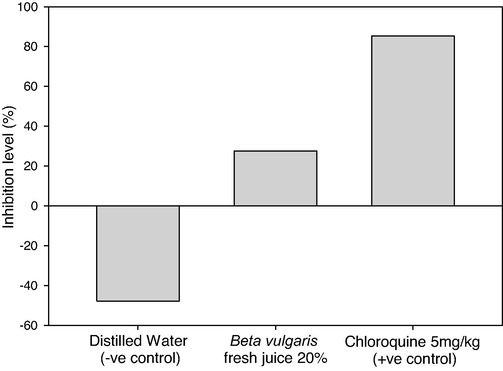

The activity of B. vulgaris fresh juice as antiplasmodial agents was perfomed in vivo and the inhibition levels of parasitemia in P. berghei infected mice were assessed (Table 1, Figs. 1, 2). In the infected mice, the mean parasitemia level was 8.11 and the inhibition % was done. The fresh juice of beetroot exhibited a good inhibitory effect of 68.92% at a survival rate of 31.08% and a mean parasitemia level of 2.52, significant differences were found in the parasitemia level between B. vulgaris fresh juice and Chloroquine at P. berghei infected mice (p = 0.0). *Parasitemia level (%): (Number of parasited RBC / Total number of examined RBC) × 100. **Inhibition level (%): Mean of (Parasitemia in negative control mice − Parasitemia in treated mice) / Mean of Parasitemia in negative control mice × 100. ***Survival rate (%): (100 − inhibition level) × 100. S.D: Standard Deviation.

Plasmodium berghei infected mice

Tested materials

Distilled water

(−ve control)

Beta vulgaris fresh juice 30 mg/kg

Chloroquine 5 mg/kg

(+ve control)

1

10

1.2

1

2

9

2.5

1

3

6

5

0

4

11

4.2

0

5

13

1

0

6

7

2.3

1

7

4

2

0.5

8

9

1.5

0

9

4

3

0

Total of parasitized RBC

73

22.7

3.5

Mean of parasitemia* ± S.D

8.11 ± 3.10

2.52 ± 1.35

0.39 ± 0.49

Inhibition level (%)**

0

68.92

95.19

Survival rate (%)***

100

31.08

4.81

Parasitemia levels in Plasmodium berghei infected mice by using doses of 30 mg/kg from Beta vulgaris fresh juice as well as 5 mg/kg Chloroquine (+ve control) and distilled water (−ve control). (*) and (#) are significant at ≤ 0.05 against non-treated and treated groups, respectively.

Inhibition levels of parasitemia in Plasmodium berghei infected mice by using doses of 30 mg/kg from Beta vulgaris fresh juice as well as 5 mg/kg Chloroquine (+ve control) and distilled water (−ve control).

3.2 Secondary screening

This screening determine the effective doses (EDs) of B. vulgaris fresh juice, following the usual 4th day suppressive test (Table 2). The activity of parasitemia inhibition was negative at the concentration 10% B. vulgaris fresh juice, the % survival rate was 100% and the level of parasitemia was high at 8.8%. The level of inhibition in 20% was 77.27% and the mean level of parasitemia and parasites survival rate decreased to 2% and 22.73% respectively, which was better than 30%, which provided an inhibition rate of 68.86%, mean parasitemia level of 2.74 and survival rate of P. berghei was 31.14%. By utilizing 40%, 60%, and 80% of fresh B. vulgaris juice, the % inhibition level decreased from 71.36% to 65.91% to 50.45%, while the mean level of parasitemia was raised from 2.52 in 40% to 3 in 60% and 4.36 in 80%, as well as the malaria survival rate, progressively increasing from 28.64% to 34.09%, and 49.99% respectively. The mean level of parasitemia was very low by 0.3 when chloroquine was used as an antimalarial agent giving an inhibition level of 96.59% compared with the negative result of distilled water, which gave 8.8 of parasitemia.

Plasmodium berghei infected mice

Tested materials

Distilled Water

(−ve control)

Beta vulgaris fresh juice

Chloroquine 5 mg/kg

(+ve control)

10%

20%

30%

40%

60%

80%

1

12

9

1

1.2

1

3

0.8

0

2

10

7

2

5

3

2

5

0.5

3

7

10

4

4.2

7

3

6

0

4

6

11

1

1

0.7

5

4

0

5

9

7

2

2.3

0.9

2

6

1

Total of parasitized RBC

44

44

10

13.7

12.6

15

21.8

1.5

Mean of parasitemia ± S.D

8.8 ± 2.39

8.8 ± 1.79

2 ± 1.22

2.74 ± 1.79

2.52 ± 2.67

3 ± 1.22

4.36 ± 2.15

0.3 ± 0.45

Inhibition level (%)

0%

0%

77.27%

68.86%

71.36%

65.91%

50.45%

96.59%

Survival rate (%)

100

100

22.73

31.14

28.64

34.09

49.99

3.41

There were significant differences in the mean parasitemia level in infected untreated mice or B. vulgaris fresh juice in concentrations ranging from 20% to 80% (p = 0.0). In addition, there was no significant difference between distilled water mice and those taking 10% of B. vulgaris fresh juice (p = 1.0), compared with the Chloroquine group, which showed no significant difference with other concentrations such as 20% (p = 0.1) and 40% (p = 0.06), while there were significant differences in fresh juice in 30% (p = 0.04), in 60% (p = 0.02) and 80% (p = 0.0).

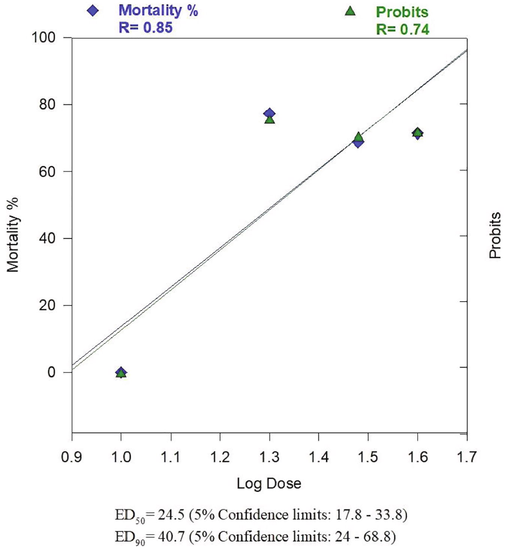

3.3 Estimation of EDs

ED50 and ED90 of B. vulgaris fresh juice gave in percentage the ED50 as 24.5 (17.8–33.8) and ED90 as 40.7 (24–68.8) at 5% confidence limits (Table 3, Fig. 3).

Materials used

Concentrations used (mg/kg)

Mean of parasitemia level

Inhibition level (%)

Inhibition concentrations with 5% confidence limits*

ED50

ED90

Beta vulgaris fresh juice

10

8.8

0

24.5

(17.8–33.8)

40.7

(24–68.8)

20

2

77.27

30

2.74

68.86

40

2.52

71.36

Distilled water (−ve control)

0

8.8

0

–

–

ED50 and ED90 (after 4 days in suppressive test) of Beta vulgaris fresh juice for inhibiting the parasitemia in Plasmodium berghei infected mice.

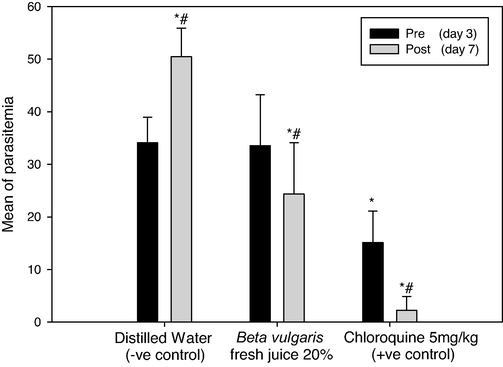

3.4 Curative test

After confirming P. berghei infection in mice, 20% of beetroot fresh juice was orally given to mice until the 7th day of infection (Table 4). Distilled water and 5 mg/kg of Chloroquine were also given to the infected mice to be negative and positive controls. Means of parasitemia levels of P. berghei on the 3rd day of infection showed 34.11 in the negative control group and it reached 50.44 after 5 days of distilled water dosage with increasing in malaria survival rate (100%). On 3rd day of infection, the treated mice groups recorded 33.56 and 15.11 in the parasitemia level by using B. vulgaris fresh juice (20%) and Chloroquine (5 mg/kg) respectively (Fig. 4). After five days of treatment, the 20% beetroot fresh juice decreased the parasitemia to 24.33 with an inhibition level of 27.5%. The most effective treated material was Chloroquine (+ve control) that showed a minimum parasitemia level of 2.22 on day 7 of infection and an inhibition level of 85.31% (Fig. 5). There were significant differences between pre and post-parasitemia levels (p = 0.0), also there were significant differences between the mice group untreated (distilled water) and other mice-treated groups (p = 0.0).

Plasmodium berghei infected mice

Tested materials

Distilled Water (−ve control)

Beta vulgaris fresh juice 20%

Chloroquine 5 mg/kg (+ve control)

Pre

Post

Pre

Post

Pre

Post

1

32

47

40

32

10

4

2

34

50

11

2

15

0

3

30

45

32

24

7

0

4

33

43

40

31

8

0

5

35

52

40

30

17

5

6

45

61

36

22

18

3

7

33

52

42

34

16

0

8

28

49

28

19

19

1

9

37

55

33

25

26

7

Total of parasitized RBC

307

454

302

219

136

20

Mean of parasitemia ± S.D

34.11 ± 4.86

50.44 ± 5.43

33.56 ± 9.64

24.33 ± 9.76

15.11 ± 6.01

2.22 ± 2.63

Inhibition level (%)

−47.87

27.5

85.31

Survival rate (%)

100

72.5

14.69

Parasitemia levels in Plasmodium berghei infected mice by using 20% of Beta vulgaris fresh juice as well as 5 mg/kg Chloroquine (+ve control) and distilled water (−ve control) following the curative test procedure. (*) and (#) are significant at ≤ 0.05 against the pre (day 3) and post-parasitemia level (day 7) in non-treated and treated groups, respectively.

Inhibition levels of parasitemia in Plasmodium berghei infected mice by using 20% of B. vulgaris fresh juice as well as 5 mg/kg Chloroquine (+ve control) and distilled water (−ve control) following the curative test procedure.

4 Discussion

The antimalarial activities of B. vulgaris fresh juice were assessed in sequential screening against the malaria rodents strain P. berghei, and the ED50 and ED90 were also estimated. There have been insufficient studies to used fresh juice against malaria infection in mice. Adegoke et al. (2011) have examined the effect of lime juice in combination with Artemisinin to clarify acute uncomplicated malaria in children. The result indicated the average period that Artemisinin combination therapy and lime therapy in children had >75% inhibition in malaria parasite was less than 30.5 ± 2.4 hrs, while Artemisinin alone had a malaria clearance of 38.6 ± 3.3 hrs. Although Adegoke et al. (2011) investigated the juice for malaria treatments; its findings cannot be compared with the results of B. vulgaris fresh juice to reduce the parasitemia caused by P. berghei, as the two major discrepancies in experimental models and different designs were employed. The link between treatment concentrations and degrees of parasitemia inhibition has not been established between all dosages of B. vulgaris fresh juice (10–80%). These results are comparable to the ones demonstrated as a different dose inhibitory agent for Paullinia pinnata ethanol leave extract (Maje et al., 2007).

Using 20% B. vulgaris fresh juice caused 77.27% malaria suppressive effect which is considered superior that no previous studies using fresh juice as an antimalarial suppressive agent. Maje et al. (2007) used 25 mg/kg of Paullinia pinnata ethanolic extract and showed antimalarial activity as 69%, while Sumsakul et al. (2014) found 41% parasitemia suppression with 25 mg/kg of Plumbago indica root extract, Plumbagin which proves that B. vulgaris fresh juice is better than those tested extracts.

Muthaura et al. (2007) reported that IC50 of aqueous and methanol extracts of Harungana madagascariensis, Warburgia stuhlmannii, Maytenus putterlickioides, Flueggea virosa, and Maytenus undata were higher than 5 g/ml against the susceptible and resistant clones of P. falciparum. Moreover, Jonville et al. (2008) noted that the IC50 of methanolic leaves extract of Aphloia theiformis, Psiadia arguta, Terminalia bentzoe, and Nuxia verticillata bark extract against the W2 and 3D7 Plasmodium strain were as 13.3, 22.4, 24.8, and 32.7 µg/ml respectively. All of these results from Muthaura et al. (2007) and Jonville et al. (2008) differ from those of B. vulgaris fresh juice results in the experimental assay type and the malaria parasite species.

The results of 5 mg/kg Chloroquine were 95.2% as inhibition of parasitemia for the suppressive test similar to those of Unekwuojo et al. (2011), but Maje et al. (2007) and Kamaraj et al. (2014) had higher inhibitor activity as 96.7% and 100%, respectively. On the other hand, Hilou et al. (2006) found an inhibition of 91% which was less than the positive Chloroquine control group. In the curative test, 5 mg/kg of Chloroquine gave 85.31% chemo-suppression which is less than 97.84% and 100% recorded by Unekwuojo et al. (2011) and Maje et al. (2007), respectively.

The red beetroot pigments are known as Betalains, split into two classes, the red-violet Betacyanins and the yellow-colored Betaxanthins (Stintzing and Carle, 2008). The red pigments in Betacyanins called betanin, it is found in the peel than in flesh (Kujala et al., 2002). Betalan pigments provide distinct health advantages owing to their nitrate concentration, including nitrogen and amino acid (Webb et al., 2008). The Red Beet peel includes the endogenous enzymes peroxidosis and b-glucosidosis, which show an evident role in protective functions by scavenging peroxides or by oxidizing other molecules (Wasserman et al., 1984). They interfere with the bloodstream of the human alimentary canal to make Betalain bioavailable to humans organisms (Netzel et al., 2005), and radical scavenging (Pedreno and Escribano, 2000; Gliszczyńska-Świgło et al., 2006; Allegra et al., 2007), were also observed.

Beetroot juice promotes the activity of liver cells and preserves the liver and bile ducts, according to Bhagyalakshmi (2012). Being drunk frequently might help alleviate constipation because of the high pectin level in the beetroot juice. Red beetroot juice mixing with carrot juice is a treatment for gout, kidney, and bile.

5 Conclusion

Therefore, the present study revealed that oral administration of beetroot fresh juice has a significant antimalarial activity as a chemosuppression agent in a model of malaria infection-induced with P. berghei ANKA, the tested doses did not produce a dose-dependent antiplasmodial effect during the curative test but the concentration of 20% recorded the highest dose of parasitemia inhibition. However, the juice might contain potential compounds for the development of novel antimalarial drugs. Hence, the experimental juice needs further evaluation to isolate and identify the active compounds.

Acknowledgements

We are sincerely grateful to all the technical staff at the Animal house unit at King Fahd Research Center, King Abdulaziz University, for their help with performing the animal experiment.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Potential antimalarials from Nigerian plants: a review. J. Ethnopharmacol.. 2011;133(2):289-302.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of lime juice on malaria parasite clearance. Phytother. Res.. 2011;25(10):1547-1550.

- [Google Scholar]

- Betanin inhibits the myeloperoxidase/nitrite-induced oxidation of human low-density lipoproteins. Free Radic. Res.. 2007;41(3):335-341.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bhagyalakshmi, N., 2012. Red Beet: An Overview in Red Beet Biotechnology: Food and Pharmaceutical Applications, edited by (Bhagyalakshmi, N. and Sowbhagya, H. Springer, pp, 12.

- The Curative and Prophylactic Effects of Xylopic Acid on Plasmodium berghei infection in mice. J. Parasitol. Res.. 2013;2013:1-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Laboratory diagnosis of malaria infection-a short review of methods. Aust. J. Med. Sci.. 2006;27(1):11-15.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antimalarial potency of the methanol leaf extract of Maerua crassifolia Forssk (Capparaceae) Asian Pac. J. Trop. Dis.. 2014;4(1):35-39.

- [Google Scholar]

- Realationship between antioxidant capacity of red beet juice and contents of its betalain pigments. Polish J. Food Nutr. Sci.. 2009;59(2):119-122.

- [Google Scholar]

- David, F., Philip, R., Simon, C., Reto, B., Solomon, N., 2004. Antimalarial drug discovery: efficacy models for compound screening. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 3(6), 509-520.

- Characterization of the antiradical activity of betalains from Beta vulgaris L. roots. Phytochem. Anal.. 1998;9(3):124-127.

- [Google Scholar]

- History of the discovery of the malaria parasites and their vectors. Parasit. Vectors. 2010;3(1):5.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Betanin, the main pigment of red beet: molecular origin of its exceptionally high free radical-scavenging activity. Food Addit. Contam.. 2006;23(11):1079-1087.

- [Google Scholar]

- Estimating the global clinical burden of Plasmodium falciparum malaria in 2007. PLoS Med.. 2010;7(6):750.

- [Google Scholar]

- In vivo antimalarial activities of extracts from Amaranthus spinosus L. and Boerhaavia erecta L. in mice. J. Ethnopharmacol.. 2006;103(2):236-240.

- [Google Scholar]

- Screening of medicinal plants from Reunion Island for antimalarial and cytotoxic activity. J. Ethnopharmacol.. 2008;120(3):382-386.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bioassay-guided isolation and characterization of active antiplasmodial compounds from Murraya koenigii extracts against Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium berghei. Parasitol. Res.. 2014;113(5):1657-1672.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chemoprevention of DMBA-induced UV-B promoted, NOR-1-induced TPA promoted skin carcinogenesis, and DEN-induced phenobarbital promoted liver tumors in mice by extract of beetroot. Pharmacol. Res.. 2003;47(2):141-148.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chemoprevention of lung and skin cancer by Beta vulgaris (beet) root extract. Cancer Lett.. 1996;100(1-2):211-214.

- [Google Scholar]

- Betalain and phenolic compositions of four beetroot (Beta vulgaris) cultivars. Eur. Food Res. Technol.. 2002;214(6):505-510.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phylum Apicomplexa: Malaria organisms and Piroplasms. In: Patrick R., ed. Foundations of Parasitology (Eighth edition). Roerig-Blong: Janice; 2009. p. :147-154.

- [Google Scholar]

- A simplified method for evaluating dose-effect experiments. J. Pharmacol. Experiment. Ther.. 1949;96(1):99-113.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of the anti-malarial activity of the Ethanolic leaves extract of Paullinia pinnata linn (Sapindaceae) Niger. J. Pharm. Sci.. 2007;6(2):67-72.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antimalarial activity of some plants traditionally used in treatment of malaria in Kwale district of Kenya. J. Ethnopharmacol.. 2007;112(3):545-551.

- [Google Scholar]

- Renal excretion of antioxidative constituents from red beet in humans. Food Res. Int.. 2005;38(8-9):1051-1058.

- [Google Scholar]

- Light-dependent betanin production by transformed cells of sugar beet. Food Technol. Biotechnol.. 2009;47(2):153-158.

- [Google Scholar]

- Studying the oxidation and the antiradical activity of betalain from beetroot. J. Biol. Educ.. 2000;35(1):49-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- Stephen, N., 2004. Beetroot (Ebook). (http://www.stephennottingham.co.uk/beetroot.htm).

- N -Heterocyclic pigments: Betalains. In: Socaciu C., ed. Food Colorants: Chemical and Functional Properties. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2008. p. :87-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antimalarial activity of plumbagin in vitro and in animal models. BMC Complement. Altern. Med.. 2014;14(1):15.

- [Google Scholar]

- Suppressive, curative and prophylactic potentials of Morinda lucida (Benth) against erythrocytic stage of mice infective chloroquine sensitive Plasmodium berghei NK-65. Br. J. Appl. Sci. Technol.. 2011;1(3):131-140.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of hydrogen peroxide and phenolic compounds on horseradish peroxidase-catalyzed decolorization of betalain pigments. J. Food Sci.. 1984;49(2):536-538.

- [Google Scholar]

- Acute blood pressure lowering, vasoprotective, and antiplatelet properties of dietary nitrate via bioconversion to nitrite. Hypertension. 2008;51(3):784-790.

- [Google Scholar]

- Development of Plasmodium chabaudi in mouse red blood cells: structural properties of the host and parasite membranes. J. Protozool.. 1982;29:60-66.

- [Google Scholar]