Effect of probiotic and synbiotic formulations on anthropometrics and adiponectin in overweight and obese participants: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials

⁎Corresponding author at: School of Public Health and Health Management, Chongqing Medical University, No. 1 Yixueyuan Road, Yuzhong District, Chongqing 400016 China. zhangyongcq@live.cn (Yong Zhang)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Accumulating evidence suggests obesity and its complication are linked to gut microbiota and probiotics can affect the metabolic functions of humans. The goal of this study was to systematically review the effect of probiotic and synbiotic formulations on body mass index (BMI), total body fat, waist circumstance (WC), Waist–hip ratio (WHR), and adiponectin in overweight and obese Participants in randomized trials (RCTs). A comprehensive search performed in PubMed/MEDLINE, Cochrane and SCOPUS by two researchers, independently without language or release date restrictions up to 15th October 2019. PRISMA guidelines followed to perform this meta-analysis. The inclusion criteria were: 1) RCT design, 2) intervention by pro or synbiotic, 3) Anthropometrics and/or adiponectin levels as outcome. DerSimonian and Laird random effect model used to combine results of included studies. Thirty-two studies contained 2105 participants (n = 28–200) were analyzed in this meta-analysis. Average length of intervention in included studies was 10.18 weeks and ranged from 3 to 12 weeks. Combined results showed significant reduction in BMI (WMD: −0.25 kg/m2; 95% CI −0.33, −0.17; I2 = 96%), total body fat (WMD: −0.75%; 95% CI −0.90, −0.61; I2 = 63%), WC (WMD: −0.99 cm; 95% CI −1.33, −0.66; I2 = 92%), and WHR (WMD: −0.01; 95% CI −0.02, 0.01; I2 = 15%) in probiotic group compared to placebo. There was no significant effect on adiponectin levels by probiotic intervention (WMD: −0.01 μg/ml; 95% CI −0.33, 0.32; I2 = 90%). Furthermore, meta-regression showed significant relation between duration of intervention and reduction of BMI (coef = −0.1533, p < 0.001) and WC (coef = −0.7131, p < 0.001). The combined results showed reduction in BMI, body fat, WC, and WHR in overweight and obese patients by supplementation with probiotics or synbiotics.

Keywords

Probiotic

Body mass index

Body fat

Adiponectin

- BMI

-

body mass index

- WC

-

waist circumstance

- WHR

-

waist–hip ratio

- RCT

-

randomized controlled trials

Abbreviations

1 Introduction

According to the World Health Organization in 2016, 39% of the global population was overweight, as defined by a body mass index (BMI) ≥25, 13% of which were obese (BMI ≥ 30) (Obesity and overweight, 2019). These figures are the result of an increase in BMI over the past 40 years and are predicted to continue to rise (Collaboration, 2016). As overweight and obesity are prominent risk factors for cardio-metabolic disease, this represents a significant public health problem requiring a multifactorial response. Current pharmacological options for weight loss have been disappointing (Rueda-Clausen and Padwal, 2014) and call for alternatives.

Pre-clinical research has suggested the gut microbiome as a potential target for weight loss. Animal models have shown that modifying the microbiome can lead to increased adiposity (Turnbaugh et al., 2006; Walker and Parkhill, 2013). Observational studies have confirmed a link between intestinal microbiome and obesity in humans (Kobyliak et al., 2016). A proposed mechanism is that gut microbes can convert otherwise indigestible polysaccharides into monomers which are not only an energy source themselves but also act as signaling molecules in pathways that affect metabolism and appetite (Gérard, 2016; Gibson et al., 2017).

It is traditionally felt that there are two main mechanisms through which the composition or metabolic activity of the gut microbiota may be modified in order to potentially achieve a health effect in the host: either by feeding of endogenous fermenting microorganisms through prebiotic supplementation, or by direct delivery of desirable exogenous microorganisms. The latter are termed probiotics and are defined as live microorganisms that are known to confer a health benefit on the host when administered in adequate amounts. The combination of both probiotics and prebiotics is commonly referred to as a synbiotic formulation. Such interventions have already been investigated for this purpose in clinical trials, which themselves have been the subjects of systematic reviews and meta-analyses (Borgeraas et al., 2018; Park and Bae, 2015; Zhang et al., 2016). The purpose of this study is to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of probiotic and synbiotic formulations for the treatment of overweight and obesity. This analysis considers BMI, percentage bodyfat, waist circumference (WC), waist-hip ratio (WHR), and adiponectin as outcomes to more precisely identify the effect of such therapeutics on adiposity. In light of the heterogeneity of probiotic preparations, this paper is also unique in including a dose-response analysis to determine an optimum probiotic dose, if indeed one exists.

2 Methods

The PRISMA statement followed to report this study (Moher et al., 2015).

2.1 Search strategy

A comprehensive search was performed in PubMed/MEDLINE, Scopus, and Cochrane databases by two reviewers, independently up to 15th October 2019. There were not any time or language limitation in literature search. Supplementary Table 1 provided search strategy containing Mesh and non-Mesh term based on each database. Furthermore, all reference lists of relevant original and review studies were scrutinized. Gray literature, review papers, and non-human studies were not included in this meta-analysis study.

2.2 Eligibility criteria

The predefined PICOS criteria (patients: overweight or obese, intervention: probiotic or synbiotic, comparator: placebo group, outcome: anthropometric parameters and adiponectin levels, study design: RCTs) used to establish included studies. The following condition considered as inclusion criteria: 1) RCT design, 2) intervention by pro or synbiotic, 3) Anthropometrics and/or adiponectin levels as outcome. The exclusion criteria were: 1) non-RCTs design, 2) in vitro or in vivo studies, 3) studies without placebo group, 4) participants <18 years old, 5) not surgery intervention.

2.3 Data extraction and quality assessment

Data extraction and quality assessment carry out by two researchers, independently. All discrepancies between them discussed and resolved by a senior author. The name of first author, publication year, number of intervention, controls, and total population, gender, location, design of study, length of intervention, dose of intervention, and Mean and SD of outcomes in baseline and post-intervention were information that extracted from included studies. Furthermore, criteria of Cochrane followed to risk of bias assessment in this studies (Higgins and Green, 2011).

2.4 Data synthesis and statistical analysis

Mean change and standard deviation (SD) of included studies considered as mine effect size of intervention and used to stablish weighted mean difference (WMD) and CI. The following formula: Mean difference = Final mean – baseline mean and SD change = SD baseline2 + SD final2 – (2 R* SD baseline + SD final) (Borenstein et al., 2009) were used to calculation the mean difference and SD of the mean difference for studies. DerSimonian and Laird random effect model used to combine results of included studies. Heterogeneity between results of included studies assessed by I2 and Q test (Higgins et al., 2003). Meta-regression analysis based on duration of intervention performed to finding heterogeneity cause among trials. In order to investigating the effect of each study on pooled results, sensitivity analysis performed. Publication bias evalueted by funnel plot, Egger’s, and Begg’s test. P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant in all test. All statistical analyses performed by Stata software version 14.

3 Results

3.1 Study selection, study characteristics, and quality assessment

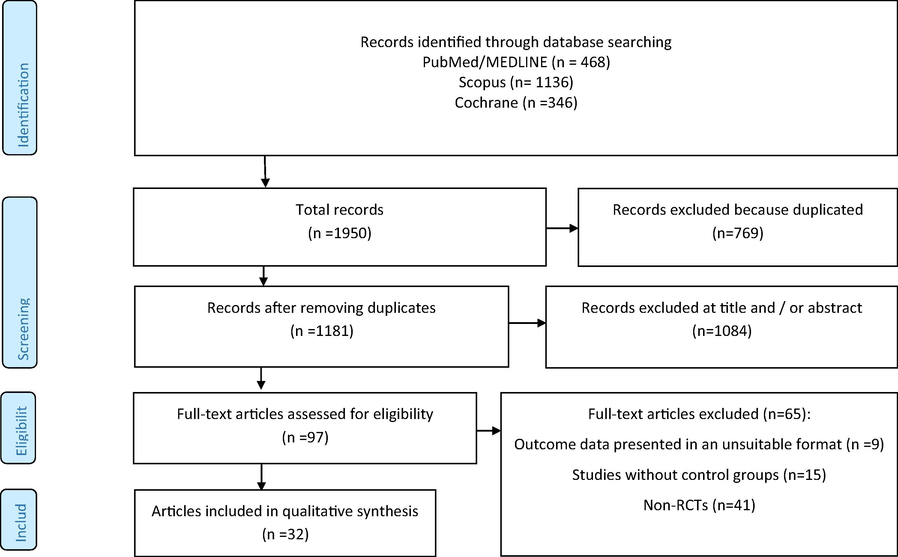

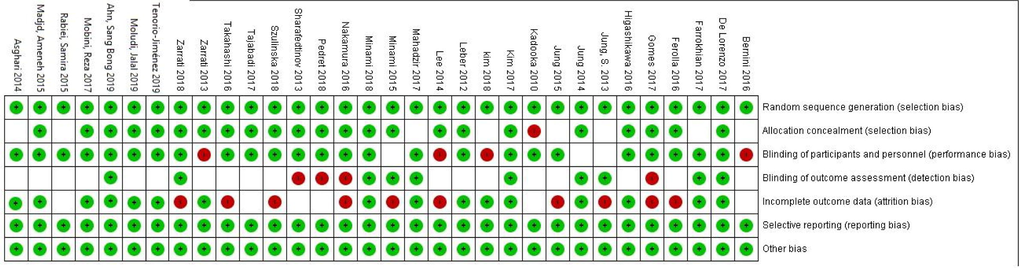

The flow diagram of literature search in PubMed/Medline, Cochrane, and Scopus databases is presented in Fig. 1. The primary literature search identified 1950 articles, of which 769 articles in due to duplication and 1084 articles in title/abstract screening were excluded. In the final step of screening, 97 papers were included for full text evaluation, of which 65 articles did not meet inclusion cretria and 32 articles were included for analysis (Ahn et al., 2019; Asghari-Jafarabadi Rad, 2014; Bernini et al., 2016; De Lorenzo et al., 2017; Farrokhian et al., 2017; Ferolla et al., 2016; Gomes et al., 2017; Higashikawa et al., 2016; Jung et al., 2014; Jung et al., 2015; Jung et al., 2013; Kadooka et al., 2010; Kim et al., 2018; Kim et al., 2017; Leber et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2014; Madjd et al., 2015; Mahadzir et al., 2017; Minami et al., 2018; Minami et al., 2015; Mobini et al., 2017; Moludi et al., 2019; Nakamura et al., 2016; Pedret et al., 2018; Rabiei et al., 2015; Sharafedtinov et al., 2013; Szulinska et al., 2018; Tajabadi-Ebrahimi et al., 2017; Takahashi et al., 2016; Tenorio-Jiménez et al., 2019; Zarrati et al., 2018; Zarrati et al., 2013). These 32 studies contained 2,105 participants (n = 28–200) and were published between the years 2010–2019. The selected characteristics of the included studies and type of probiotic applied are presented in Table 1. Average length of intervention in included studies was 10.18 weeks and ranged from 3 to 12 weeks. Four studies of included papers were conducted in females only (De Lorenzo et al., 2017; Gomes et al., 2017; Lee et al., 2014; Madjd et al., 2015), while all other studies included both genders. The age range of participants age was 18–85 years. The risk of bias in included studies is presented in Fig. 2. Risk of bias assessment was assessed with the Cochrane Collaboration tool and included studies were found to be of good quality.

- Flow chart of included studies.

| Author | Location | Year | Participants (n) | Gender | Age (years) | Formulation/Dose | Duration (week) | Participant Classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zarrati | Iran | 2018 | 56 | M/F | 20–50 | 200 g/day probiotic yogurt containing Lactobacillus acidophilus La5, Bifidobacterium BB12 and Lactobacillus casei DN001 (108 CFU/g each 200 g yogurt) | 8 | Overweight, obese |

| Szulinska | Poland | 2018 | 71 | F | 45–70 | The HD group received Ecologic® Barrier HD (1 × 1010 colony forming units (CFU) per day divided in two equal doses), whereas the LD group received Ecologic® Barrier LD (2.5 × 109 colony forming units (CFU) per day divided in two equal doses | 12 | Obesity |

| Pedret | Spain | 2018 | 126 | M/F | >18 | ii) Ba8145, 100 mg of the live strain, 1010 colony forming unit (CFU)/capsule containing maltodextrin 200 mg, or iii) h-k Ba8145, 100 mg of heat-killed CECT 8145 strain at a concentration of 1010 CFU before the heat treatment/capsule containing maltodextrin 200 mg. | 12 | Abdominal obesity |

| Minami | Japan | 2018 | 80 | M/F | 20–64 | Lyophilized powder of live B. breve B-3 (10 billion CFU per capsule) 2 capsules/d | 12 | Pre-obesity |

| Kim | Korea | 2018 | 90 | M/F | 20–75 | the low dose of L. gasseri BNR17 (BNR-L) group, or the high dose of L. gasseri BNR17 (BNR-H) group for | 12 | Obesity |

| Kim | Korea | 2017 | 66 | M/F | 2 g of probiotic powder twice a day (after breakfast and dinner) containing L. curvatus HY7601 (2.5 × 109 colony-forming units (CFU)) and L. plantarum KY1032 (2.5 × 109 CFU) | 12 | Overweight, obese | |

| Gomes | Brazil | 2017 | 43 | F | 20–59 | 4 sachet/d of maltodextrin (48.3%), modified starch (24.21%), xylitol (24.21%), silicium dioxide (0.97%), and 1 3 109 CFU of each of the probiotic strains: Lactobacillus acidophilus LA-14, Lactobacillus casei LC-11, Lactococcus lactis LL-23, Bifidobacterium bifidum BB-06, and Bifidobacterium lactis BL-4 (Danisco) | 8 | Overweight, obese |

| De Lorenzo | Italy | 2017 | 48 | F | not reported 24–56 | n.1 bag of POS/d | 3 | Obesity |

| Tajabadi-Ebrahimi | Iran | 2017 | 60 | m/f | 40–85 | 3 Probiotic bacteria spices Lactobacillus acidophilus 2 × 109, Lactobacillus casei 2 × 109, Bifidobacterium bifidum 2 × 109 CFU/g | 8 | T2D, overweight, stable CHD |

| Mahadzir | Malaysia | 2017 | 24 | M/F | 18–50 | 2 Sachets/d | 4 | Overweight |

| Farrokhian | Iran | 2017 | 60 | M/F | 40–85 | Capsule/day | 12 | Overweight, obesity, T2D |

| Takahashi | Japan | 2016 | 137 | M/F | 20–65 | Fermented milk (FM) containing B. lactis GCL2505 (approximately 8 × 1010 colony forming units [CFU]/100 g) | 12 | Overweight, obese |

| Nakamura | Japan | 2016 | 200 | M/F | >18 | 200 mg of the fragmented CP1563 | 12 | Overweight, pre-obese |

| Higashikawa | Japan | 2016 | 41 | M/F | 20–70 | 10-ml spoon for the living LP28 group and a 7.5-ml spoon for the heat-killed LP28 and placebo groups. The cell numbers in both 10 ml of the living LP28 and 7.5 ml of the heat-killed LP28 were 1011 once/d | 12 | Overweight |

| Ferolla | Brazil | 2016 | 49 | M/F | 25–74 | 108 CFU of L. reuteri, twice daily | 12 | NASH |

| Bernini | Brazil | 2016 | 51 | ? | 18–60 | 0 ml of the probiotic milk containing on average 3.4 108 colonyforming units (CFU)/mL of B. animalis ssp. lactis ssp. nov. HN019. | 6 | Metabolic syndrome |

| Minami | Japan | 2015 | 44 | M/F | 40–69 | 5 × 1010 colony-forming units per three capsules by microbial colony/d | 12 | Overweight |

| Jung | Korea | 2015 | 95 | M/F | 20–65 | 2 g of powder of two probiotic strains, L. curvatus HY7601 and L. plantarum KY1032, each at 2.5 × 109 cfu, twice a day (immediately after breakfast and dinner) | 12 | Overweight |

| Lee | Korea | 2014 | 36 | F | 19–65 | 5 Billion viable cells of Streptococcus thermophiles (KCTC 11870BP), Lactoba-cillus plantarum (KCTC 10782BP), Lactobacillus acidophilus (KCTC11906BP), Lactobacillus rhamnosus (KCTC 12202BP), Bifidobacteriumlactis (KCTC 11904BP), Bifidobacterium longum (KCTC 12200BP), and Bifidobacterium breve (KCTC 12201BP). twice/d | 8 | Obesity, dysbiosis |

| Jung | Korea | 2014 | 54 | 20–50 | Yeast hydrolysate | 10 | Obesity | |

| Zarrati | Iran | 2013 | 50 | M/F | 20–50 | 1 * 108 cfu/mL 3 times/week | 8 | Obesity, overweight |

| Sharafedtinov | Estonia | 2013 | 40 | M/F | 30–69 | 1.5x1011 CFU/g | 3 | Obesity, HTN |

| Jung | Korea | 2013 | 62 | M/F | 19–60 | 1010 CFU of Lb. gasseri BNR17 in capsule. 6 capsules/d | 12 | Obesity, overweight |

| Leber | Austria | 2012 | 28 | M/F | 24–66 | 65 ml of YAKULT light (containing L. casei Shirota at a concentration of 108/ml, Yakult Austria, Vienna) per day | 12 | Metabolic syndrome |

| Asghari-Jafarabadi Rad | Iran | 2014 | 72 | M/F | 43 | Commercial probiotic yogurt .starter microbiota of Lactobacillus bulgaricus and Streptococcus thermophilus; addition of probiotic Lactobacillus acidophilus La5 and Bifidobacterium lactis Bb Dosage: 300 g daily |

8 | Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease |

| Madjd, Ameneh | Iran | 2015 | 89 | F | 31 | Low-fat probiotic yogurt (starter cultures of Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactobacillus bulgaricus) enriched with probiotic Lactobacillus acidophilus LA5 and Bifidobacterium lactis BB12 (Dosage: 400 g consumed with main meals (200 g twice daily, with lunch and dinner) | 12 | Healthy obese |

| Rabiei, Samira | Iran | 2015 | 40 | M/F | 58 | Synbiotic capsules containing Lactobacillus casei, Lactobacillus rhamnosus, Streptococcus thermophilus, Bifidobacterium breve, Lactobacillus acidophilus, Bifidobacterium longum, and Lactobacillus bulgaricus. Dosage: 2 capsules daily | 12 | Metabolic syndrome |

| Mobini, Reza | Iran | 2017 | 44 | M/F | 65 | Low dose: Commercial probiotic powder administered to supply 108 CFU of Lactobacillus reuteri, High dose: Commercial probiotic powder administered to supply Lactobacillus reuteri Dosage: 1 dose added to water once daily | 12 | Type 2 Diabetes |

| Ahn, Sang Bong | Korea | 2019 | 65 | M/F | 43 | A probiotic mixture of L. acidophilus CBT LA1, L. rhamnosus CBT LR5 isolated from Korean human feces, L. paracasei CBT LPC5 isolated from Korean fermented food (jeotgal), P. pentosaceus CBT SL4 isolated from a Korean fermented vegetable product (kimchi), B. lactis CBT BL3, and B. breve CBT BR3 isolated from Korean infant feces | 12 | Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease |

| Moludi, Jalal | Iran | 2019 | 44 | M/F | 52 | Probiotic freezedried LGG or placebo (maltodextrin,150 mg/day) | 12 | Coronary Artery Diseases |

| Tenorio-Jiménez, Carmen | Spain | 2019 | 53 | M/F | – | Capsule containing either the probiotic L. reuteri V3401 | 12 | Metabolic Syndrome |

| Kadooka | Japan | 2010 | 87 | M/F | 33–63 | 5*1010 cfu/100 g of Lactobacillus gasseri SBT2055 | 12 | abdominal obesity |

- Cochrane risk of bias assessment.

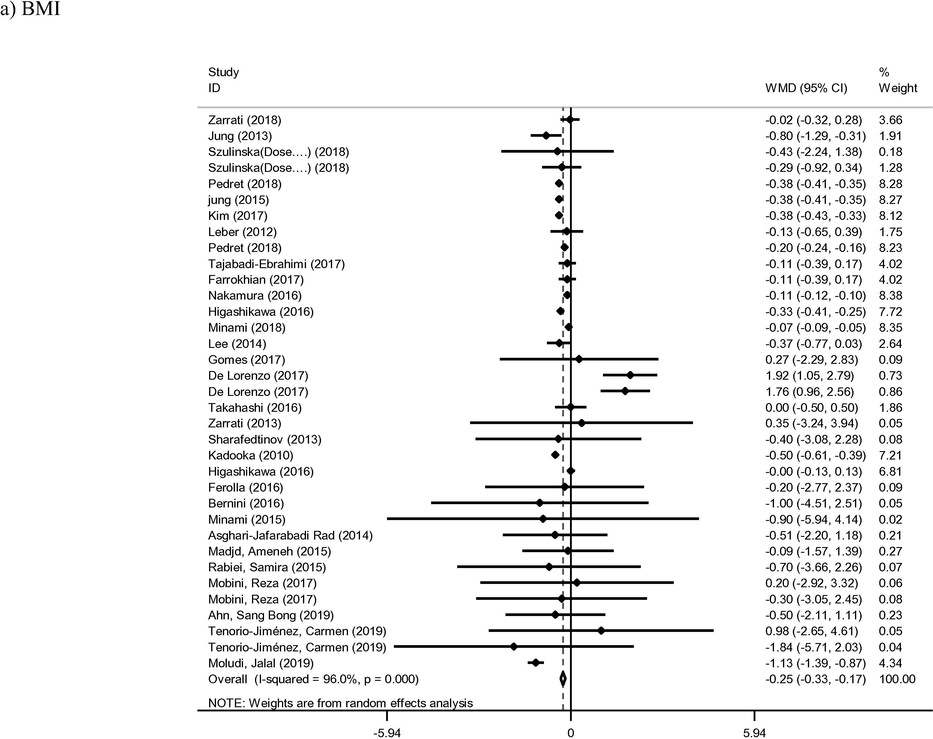

3.2 BMI and percentage %body fat

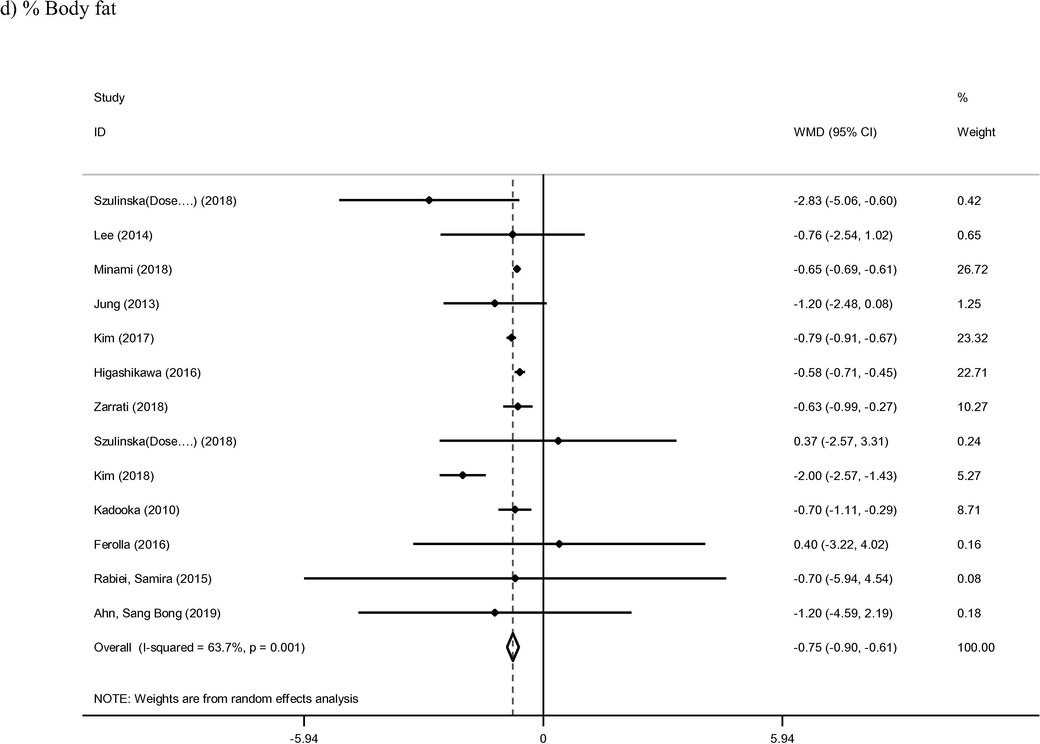

Thirty-five arms of included studies met inclusion criteria for BMI outcome and were therefore included in the present analysis (Ahn et al., 2019; Asghari-Jafarabadi Rad, 2014; Bernini et al., 2016; De Lorenzo et al., 2017; Farrokhian et al., 2017; Ferolla et al., 2016; Gomes et al., 2017; Higashikawa et al., 2016; Jung et al., 2015; Jung et al., 2013; Kadooka et al., 2010; Kim et al., 2018; Kim et al., 2017; Leber et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2014; Madjd et al., 2015; Mahadzir et al., 2017; Minami et al., 2018; Minami et al., 2015; Mobini et al., 2017; Moludi et al., 2019; Nakamura et al., 2016; Pedret et al., 2018; Rabiei et al., 2015; Sharafedtinov et al., 2013; Szulinska et al., 2018; Tajabadi-Ebrahimi et al., 2017; Takahashi et al., 2016; Tenorio-Jiménez et al., 2019; Zarrati et al., 2018; Zarrati et al., 2013). The intervention group was found to confer a significant reduction in BMI when compared to the controls (WMD: −0.25 kg/m2; 95% CI −0.33, −0.17; I2 = 96%) (Fig. 3). Meta-regression analysis based on length of intervention was identified as a source of heterogeneity between study outcomes (Supplemental Fig. 1). BMI was found to reduce accordingly with increasing time of intervention (coef = −0.1533, p < 0.001). Furthermore, ten studies containing thirteen arms reported on percentage of body fat as a primary outcome (Ahn et al., 2019; Ferolla et al., 2016; Higashikawa et al., 2016; Jung et al., 2013; Kadooka et al., 2010; Kim et al., 2018; Kim et al., 2017; Lee et al., 2014; Minami et al., 2018; Rabiei et al., 2015; Szulinska et al., 2018; Zarrati et al., 2018). Pooled results from included studies with a random effect model showed significant reduction the parameter in probiotic group compared to control group (WMD: −0.75%; 95% CI −0.90, −0.61; I2 = 63%). The duration of intervention displayed an inverse effect on percentage bodyfat (coef = −0.0670), although this relationship was not found to be statistically significant (p = 0.57).

- Meta-analysis of effect of probiotic consumption on:

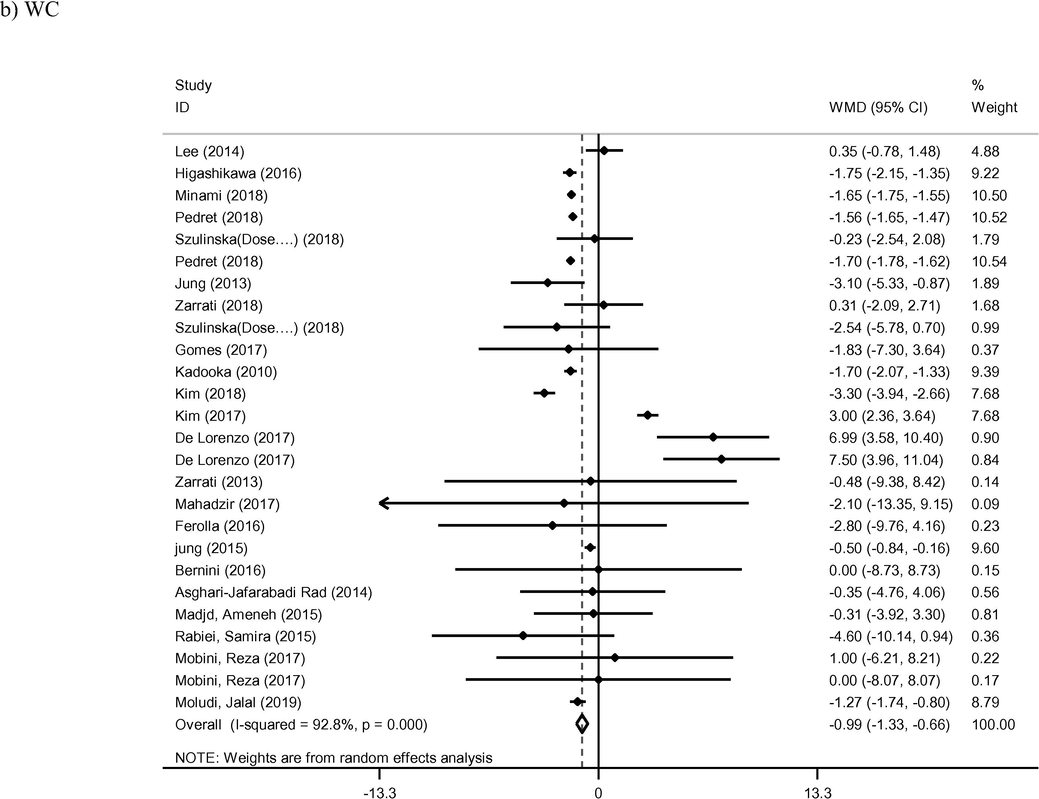

- Meta-analysis of effect of probiotic consumption on:

- Meta-analysis of effect of probiotic consumption on:

- Meta-analysis of effect of probiotic consumption on:

- Meta-analysis of effect of probiotic consumption on:

3.3 WC and WHR

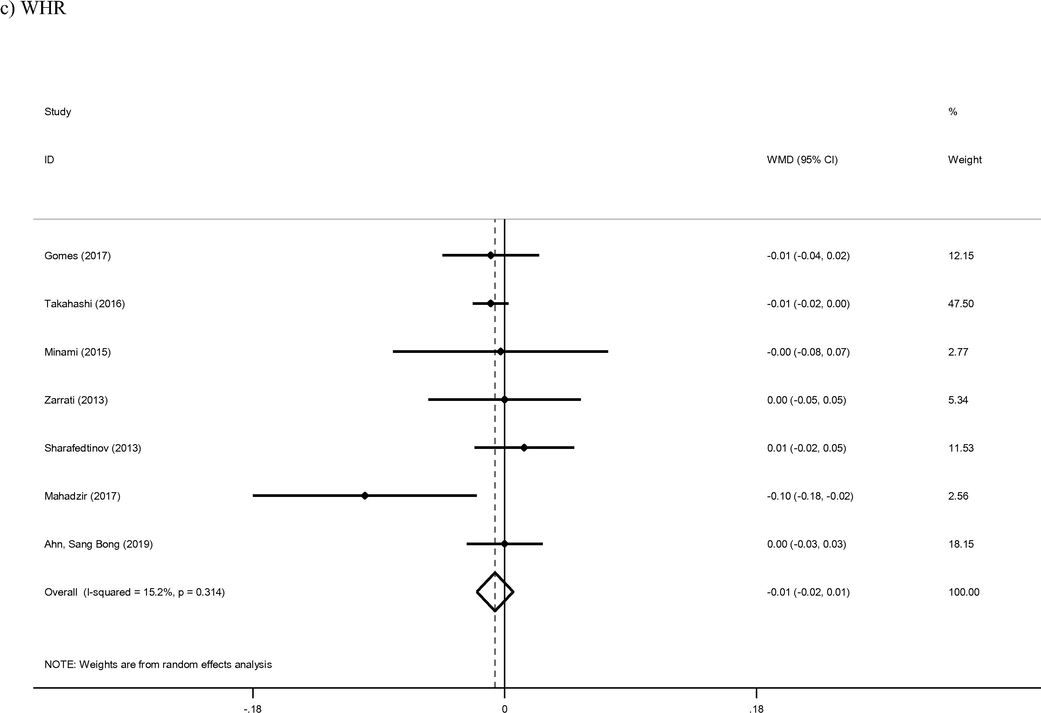

Twenty-six arms of included studies reported on WC as a primary outcome (Asghari-Asghari-Jafarabadi Rad, 2014; Bernini et al., 2016; De Lorenzo et al., 2017; Ferolla et al., 2016; Gomes et al., 2017; Higashikawa et al., 2016; Jung et al., 2015; Jung et al., 2013; Kadooka et al., 2010; Kim et al., 2018, 2017; Lee et al., 2014; Madjd et al., 2015; Mahadzir et al., 2017; Minami et al., 2018; Minami et al., 2015; Mobini et al., 2017; Moludi et al., 2019; Pedret et al., 2018; Rabiei et al., 2015; Szulinska et al., 2018; Zarrati et al., 2018; Zarrati et al., 2013). The reduction of WC was found to be statistically significant in the intervention group compared to the control group (WMD: −0.99 cm; 95% CI −1.33, −0.66; I2 = 92%). Finally, meta-regression of WC also identified length of intervention as a key mediator of effect (coef = −0.7131, p < 0.001). Seven studies provided sufficient data for analysis of WHR as an outcome of probiotic therapy (Ahn et al., 2019; Gomes et al., 2017; Mahadzir et al., 2017; Minami et al., 2015; Sharafedtinov et al., 2013; Takahashi et al., 2016; Zarrati et al., 2013). The reduction of WHR in intervention group wan not found to be statistically significant compared control group (WMD: −0.01; 95% CI −0.02, 0.01; I2 = 15%).

3.4 Adiponectin

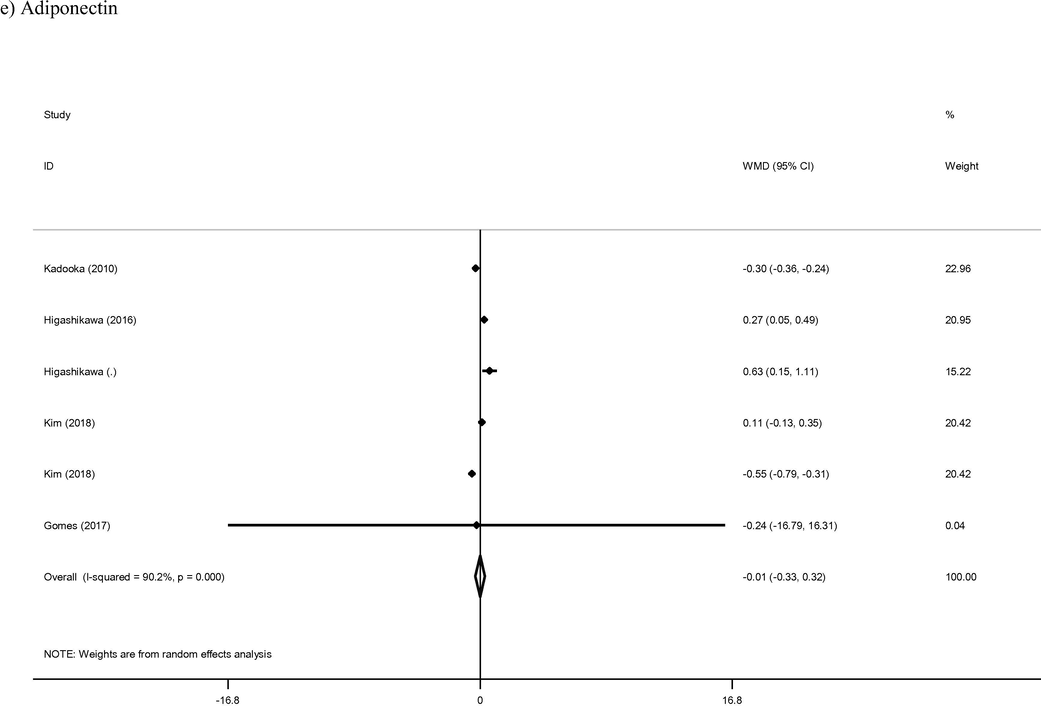

Combined analysis of the six arms from five studies which reported on adiponectin levels demonstrated no alteration in levels of the hormone in intervention group compared to control group (WMD: −0.01 μg/ml; 95% CI −0.33, 0.32; I2 = 90%). Although duration of intervention appeared to have a direct effect on adiponectin levels (coef = 0.0299), this relationship was not statistically significant (p = 0.99).

3.5 Publication bias and sensitivity analysis

The Funnel plot, Begg's rank correlation test, and Egger's regression asymmetry test were used to identify publication bias between studies. The funnel plots do not display significant asymmetry among the studies for any outcome assessed (Supplemental Fig. 2). The Begg’s rank correlation test and Egger’s regression asymmetry test results are provided in Supplementary Table 2. The Begg’s and Egger’s regression tests were not found significant publication bias among included studies. As highlighted in Supplemental Fig. 3, the sensitivity analysis shows not significant differences beyond the limits of 95% CI of combined results for each of included studies.

4 Discussion

The field of microbiota and probiotic research has been a promising and ever-evolving area in terms of potential novel therapies for a wide range of diseases, in particular those which are cardiometabolic in nature (Ryan et al., 2015, 2017). Although a great deal of preclinical data exists supporting the application of certain microbial therapeutics for complexes such as obesity and cardiovascular disease, similar data in clinical cohorts had been relatively scarce until recent years. In addition, many of these trials may be deemed relatively underpowered to detect the degree of benefit expected. In line with this, the current systematic review and meta-analysis set-out to synthesize all available data concerning the use of probiotics and synbiotics in the control of adiposity of overweight and obese subjects. This study revealed a clear and significant beneficial effect of such interventions in terms of BMI, WC, and percentage bodyfat reduction; however, no significant alteration to WHR could be detected from the studies analyzed. In an effort to explore the potential molecular underpinnings of these beneficial effects, data on the levels of adiponectin from a subset of studies was assessed, although this revealed no effect of the interventions. Taken together, the results of this meta-analysis suggest that probiotic and synbiotic formulations may represent promising adjunctive therapies in the control of obesity and its associated metabolic comorbidities.

Overall, probiotic and synbiotic interventions were found to have a modest but consistent effect on BMI and WC in the meta-analysis conducted. Moreover, the duration of intervention was found to be a substantial contributory factor in the efficacy of each formulation. The mechanisms underlying these effects and attributes are not entirely obvious, although several complementary theories have been offered. For instance, Jung et al. also investigated Lp-PLA2 and oxidized-LDL levels in both probiotic and placebo groups at study completion and found that the former significantly reduced both marker, suggesting that the probiotic formulation significantly reduced the inflammatory and oxidative profile of the participants in a manner which may contribute to its anti-obesity effects (Jung et al., 2015). Alternatively, probiotic bacteria are commonly known to secrete a range of potentially bioactive metabolites, including short-chain fatty acids, serotonin, tryptophan and gamma-aminobutyric acid (Patterson et al., 2016). Short-chain fatty acids, which are produced as fermentation products from the microbial digestion of carbohydrates, have been shown to impact upon host energy homeostasis and appetite through their agonistic effects on several enterocyte G-protein coupled receptors and gut hormones (Byrne et al., 2015). In addition, a recent preclinical study examining the effects of gamma-aminobutyric acid secreting lactobacilli found that the probiotics reduced percentage bodyfat, in particular the mesenteric adipose tissue (Patterson et al., 2019). Such microbes may represent a novel generation of probiotics which may prove to be efficacious in reducing truncal obesity in human subjects.

The majority of the included studies assessed BMI and WC in participants, while just six studies concerned themselves with WHR as a primary outcome. While BMI remains the gold standard assessment of patient body habitus, there is evidence to suggest that WC and WHR may be more indicative of the central or truncal obesity which is known to be associated with cardiometabolic disease (Welborn et al., 2003). The reasons for the failure to detect an effect of the interventions on WHR are not entirely clear at present. There is evidence to suggest that BMI correlates more closely with WC than WHR (Ahmad et al., 2016). However, it is important to note that each of the studies which reported WHR also reported a concurrent lack of effect on BMI or WC. In other terms, none of the studies in which the intervention which successfully reduced BMI or WC also assessed WHR concurrently. Therefore, it would be important to assess the effects of the successful BMI and WC reducing regimens on WHR in future investigations.

Adiponectin is an adipocyte-derived hormone which is found to be paradoxically reduced in overweight and obese individuals (Arita et al., 1999). The role of the adipokine in metabolic disease has been explored for several years now, with multiple epidemiological studies displaying inverse associations with insulin resistance (Mojiminiyi et al., 2007) and several biomarkers of cardiometabolic disease, such as low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (Bansal et al., 2006) and triglycerides (Komatsu et al., 2007). It is thought that adiponectin acts by both improving insulin sensitivity and increasing fatty acid beta-oxidation (Yamauchi et al., 2002), thereby improving the metabolic profile of the individual. Despite the pooled reduction in BMI, WC and percentage bodyfat, no significant effect of probiotics on adiponectin could be detected. In fact, only two of the six arms analyzed actually reported a statistically significant reduction in the hormone independently. Interesting, however, is the fact that both arms were assessing the efficacy of L. gasseri strains of probiotics. This suggests that the probiotic formulations assessed to date did not affect total adiposity to a degree which could alter the levels of this metabolically active hormone.

4.1 Strengths & limitations

As the field is now expanding rapidly with new clinical data available regularly, the present study builds upon previous meta-analyses by synthesizing a substantially greater number of cohorts and participants, making this the largest analysis of the topic. Despite this, a considerable degree of heterogeneity was detected within the meta-analyses, particularly with respect to those concerning BMI and WC. This indeed suggests that there are additional factors which may be contributing to variance between these outcomes in the assessed studies and a degree of scrutiny into these potential confounders is prudent. Moreover, the cohorts included in this analysis were generally of relatively small size (n = 28–200) and varied in their metabolic definition (i.e., overweight, obese, metabolic syndrome) and reported comorbidities, such as diabetes and hypertension. The impact which this may have on the efficacy of such therapeutics is not clear at present. Similarly, the variation in intervention formulation between probiotics (bacteria alone) and synbiotics (bacteria with a non-digestible carbohydrate) may be important to consider, as the latter is far more likely to impact upon the composition and, in turn, functionality of the intestinal microbiota (Verkhnyatskaya et al., 2019).

In the interest of homogeneity of intervention, the current study did not consider several more recent microbial therapies which are somewhat removed from the Generally Regarded as Safe (GRAS)-status lactobacilli and bifidobacterial that traditionally define the probiotic domain. Perhaps most notable in this regard is Akkermansia muciniphila, a species of the phylum Verrucomicrobia, the abundance of which has repeated been found to be associated with metabolic fitness (Karlsson et al., 2012) and which was recently the focus of a pilot RCT examining the effects of its oral consumption on lipid profile and insulin resistance (Depommier et al., 2019). Although this is potentially a limitation worth considering, there is limited clinical data surrounding such microbes at present and their inclusion would likely serve only to bolster the current conclusions. Finally, as more clinical data becomes available, it will be prudent to further stratify interventions taxonomically, since it is generally accepted that probiotics display a significant degree of interspecies variation with regards to their potential health impact (O'Shea et al., 2012).

5 Conclusion

With obesity rates climbing in a landscape where efficacious non-surgical anti-obesity interventions are scarce, the potential use of probiotic and synbiotic formulation in weight management has become of significant interest to metabolic researchers. However, the efficacy of such interventions to reduce adiposity in a clinical setting remains disputable at present. As the majority of studies to date have involved relatively modest cohorts of individuals, the present systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to synthesize all available RCT data in the field in order to assess their potential. In the present analysis, which included 25 studies containing 1698 participants, the composite intervention representing both probiotic and synbiotic formulations demonstrated the potential to reduce BMI, WC and percentage bodyfat, while no effect on WHR or circulating adiponectin levels could be detected. In addition, meta-regression revealed a significant association was between duration of intervention and degree of BMI and WC reduction. These results indicate that such nutraceuticals may have a role as safe and tolerable weight controlling interventions which could be implemented in conjunction with lifestyle adjustments.

Funding

None.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Abdominal obesity indicators: waist circumference or waist-to-hip ratio in Malaysian adults population. Int. J. Prev. Med.. 2016;7:82.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of a multispecies probiotic mixture in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Sci. Rep.. 2019;9(1):5688.

- [Google Scholar]

- Paradoxical decrease of an adipose-specific protein, adiponectin, in obesity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun.. 1999;257(1):79-83.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The effect of probiotic and conventional yogurt consumptions on anthropometric parameters in individuals with non alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Babol Univ. Med. Sci.. 2014;16(9):55-62.

- [Google Scholar]

- Adiponectin in umbilical cord blood is inversely related to low-density lipoprotein cholesterol but not ethnicity. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab.. 2006;91(6):2244-2249.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Beneficial effects of Bifidobacterium lactis on lipid profile and cytokines in patients with metabolic syndrome: A randomized trial. Effects of probiotics on metabolic syndrome. Nutrition (burbank, los angeles county calif.). 2016;32(6):716-719.

- [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein, M., Cooper, H., Hedges, L., & Valentine, J. (2009). Effect sizes for continuous data. The handbook of research synthesis and meta-analysis, vol. 2, pp. 221–235

- Effects of probiotics on body weight, body mass index, fat mass and fat percentage in subjects with overweight or obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obes. Rev.. 2018;19(2):219-232.

- [Google Scholar]

- The role of short chain fatty acids in appetite regulation and energy homeostasis. Int. J. Obes. (Lond.). 2015;39(9):1331-1338.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Trends in adult body-mass index in 200 countries from 1975 to 2014: a pooled analysis of 1698 population-based measurement studies with 19· 2 million participants. Lancet. 2016;387(10026):1377-1396.

- [Google Scholar]

- Can psychobiotics intake modulate psychological profile and body composition of women affected by normal weight obese syndrome and obesity? a double blind randomized clinical trial. J. Transl. Med.. 2017;15(1):135.

- [Google Scholar]

- Supplementation with Akkermansia muciniphila in overweight and obese human volunteers: a proof-of-concept exploratory study. Nat. Med.. 2019;25(7):1096-1103.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The Effects of Synbiotic Supplementation on Carotid Intima-Media Thickness, Biomarkers of Inflammation, and Oxidative Stress in People with Overweight, Diabetes, and Coronary Heart Disease: a Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins 2017

- [Google Scholar]

- Beneficial effect of synbiotic supplementation on hepatic steatosis and anthropometric parameters, but not on gut permeability in a population with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Nutrients. 2016;8(7)

- [Google Scholar]

- Expert consensus document: The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of prebiotics. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol.. 2017;14(8):491.

- [Google Scholar]

- The additional effects of a probiotic mix on abdominal adiposity and antioxidant Status: a double-blind, randomized trial. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2017;25(1):30-38.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antiobesity effect of Pediococcus pentosaceus LP28 on overweight subjects: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr.. 2016;70(5):582-587.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions 5.1. 0. Cochrane Collab. 2011:33-49.

- [Google Scholar]

- Yeast hydrolysate can reduce body weight and abdominal fat accumulation in obese adults. Nutrition. 2014;30(1):25-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- Supplementation with two probiotic strains, Lactobacillus curvatus HY7601 and Lactobacillus plantarum KY1032, reduced body adiposity and Lp-PLA2 activity in overweight subjects. J. Funct. Foods. 2015;19:744-752.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of Lactobacillus gasseri BNR17 on overweight and obese adults: a randomized, double-blind clinical trial. Korean J. Fam. Med.. 2013;34(2):80-89.

- [Google Scholar]

- Regulation of abdominal adiposity by probiotics (Lactobacillus gasseri SBT2055) in adults with obese tendencies in a randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr.. 2010;64(6):636-643.

- [Google Scholar]

- The microbiota of the gut in preschool children with normal and excessive body weight. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2012;20(11):2257-2261.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lactobacillus gasseri BNR17 supplementation reduces the visceral fat accumulation and waist circumference in obese adults: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled Trial. J. Med. Food. 2018;21(5):454-461.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of weight loss using supplementation with Lactobacillus strains on body fat and medium-chain acylcarnitines in overweight individuals. Food Funct.. 2017;8(1):250-261.

- [Google Scholar]

- Probiotics in prevention and treatment of obesity: a critical view. Nutrit. Metab.. 2016;13(1):14.

- [Google Scholar]

- Adiponectin inversely correlates with high sensitive C-reactive protein and triglycerides, but not with insulin sensitivity, in apparently healthy Japanese men. Endocr. J.. 2007;54(4):553-558.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The influence of probiotic supplementation on gut permeability in patients with metabolic syndrome: an open label, randomized pilot study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr.. 2012;66(10):1110-1115.

- [Google Scholar]

- The effects of co-administration of probiotics with herbal medicine on obesity, metabolic endotoxemia and dysbiosis: a randomized double-blind controlled clinical trial. Clin. Nutr.. 2014;33(6):973-981.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of the effect of daily consumption of probiotic compared with low-fat conventional yogurt on weight loss in healthy obese women following an energy-restricted diet: a randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutrit.. 2015;103(2):323-329.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of probiotic microbial cell preparation (MCP) on fasting blood glucose, body weight, waist circumference, and faecal short chain fatty acids among overweight Malaysian adults: a pilot randomised controlled trial of 4 weeks. Malaysian J. Nutrit.. 2017;23(3):329-341.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of Bifidobacterium breve B-3 on body fat reductions in pre-obese adults: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Biosci. Microbiota Food Health. 2018;37(3):67-75.

- [Google Scholar]

- Oral administration of Bifidobacterium breve B-3 modifies metabolic functions in adults with obese tendencies in a randomised controlled trial. J. Nutr. Sci.. 2015;4:e17

- [Google Scholar]

- Metabolic effects of L actobacillus reuteri DSM 17938 in people with type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Obes. Metab.. 2017;19(4):579-589.

- [Google Scholar]

- Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic Rev.. 2015;4(1):1.

- [Google Scholar]

- Adiponectin, insulin resistance and clinical expression of the metabolic syndrome in patients with Type 2 diabetes. Int. J. Obes. (Lond.). 2007;31(2):213-220.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Interactive effect of probiotics supplementation and weight loss diet on metabolic syndrome features in patients with coronary artery diseases: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2019 1559827619843833

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of fragmented Lactobacillus amylovorus CP1563 on lipid metabolism in overweight and mildly obese individuals: a randomized controlled trial. Microb. Ecol. Health Dis.. 2016;27:30312.

- [Google Scholar]

- Production of bioactive substances by intestinal bacteria as a basis for explaining probiotic mechanisms: bacteriocins and conjugated linoleic acid. Int. J. Food Microbiol.. 2012;152(3):189-205.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Obesity and overweight. (2019, 2019/11/07/). Retrieved from https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight.

- Probiotics for weight loss: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr. Res.. 2015;35(7):566-575.

- [Google Scholar]

- Gut microbiota, obesity and diabetes. Postgrad. Med. J.. 2016;92(1087):286-300.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Gamma-aminobutyric acid-producing lactobacilli positively affect metabolism and depressive-like behaviour in a mouse model of metabolic syndrome. Sci. Rep.. 2019;9

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effects of daily consumption of the probiotic Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis CECT 8145 on anthropometric adiposity biomarkers in abdominally obese subjects: a randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Obes. (Lond.) 2018

- [Google Scholar]

- The effects of symbiotic therapy on anthropometric measures, body composition and blood pressure in patient with metabolic syndrome: a triple blind RCT. Med. J. Islamic Republic Iran. 2015;29:213.

- [Google Scholar]

- Functional food addressing heart health: do we have to target the gut microbiota? Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care. 2015;18(6):566-571.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bile acids at the cross-roads of gut microbiome-host cardiometabolic interactions. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr.. 2017;9:102.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hypocaloric diet supplemented with probiotic cheese improves body mass index and blood pressure indices of obese hypertensive patients–a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled pilot study. Nutr. J.. 2013;12:138.

- [Google Scholar]

- Dose-Dependent Effects of Multispecies Probiotic Supplementation on the Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) Level and Cardiometabolic Profile in Obese Postmenopausal Women: a 12-Week Randomized Clinical Trial. Nutrients. 2018;10(6)

- [Google Scholar]

- A randomized controlled clinical trial investigating the effect of synbiotic administration on markers of insulin metabolism and lipid profiles in overweight type 2 diabetic patients with coronary heart disease. Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes. 2017;125(1):21-27.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of Bifidobacterium animalis ssp. lactis GCL2505 on visceral fat accumulation in healthy Japanese adults: a randomized controlled trial. Biosci. Microbiota Food Health. 2016;35(4):163-171.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lactobacillus reuteri V3401 reduces inflammatory biomarkers and modifies the gastrointestinal microbiome in adults with metabolic syndrome: the PROSIR Study. Nutrients. 2019;11(8):1761.

- [Google Scholar]

- An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature. 2006;444(7122):1027.

- [Google Scholar]

- Shaping the infant microbiome with non-digestible carbohydrates. Front. Microbiol.. 2019;10:343.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Waist-hip ratio is the dominant risk factor predicting cardiovascular death in Australia. Med. J. Aust.. 2003;179(11–12):580-585.

- [Google Scholar]

- Adiponectin stimulates glucose utilization and fatty-acid oxidation by activating AMP-activated protein kinase. Nat. Med.. 2002;8(11):1288-1295.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effects of probiotic yogurt on serum omentin-1, adropin, and nesfatin-1 concentrations in overweight and obese participants under low-calorie diet. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins 2018

- [Google Scholar]

- Lactobacillus acidophilus La5, Bifidobacterium BB12, and Lactobacillus casei DN001 modulate gene expression of subset specific transcription factors and cytokines in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of obese and overweight people. BioFactors (Oxford, England). 2013;39(6):633-643.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of probiotics on body weight and body-mass index: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr.. 2016;67(5):571-580.

- [Google Scholar]

Appendix A

Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2020.01.011.

Appendix A

Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article: