Translate this page into:

An in vitro and in silico antidiabetic approach of GC–MS detected friedelin of Bridelia retusa

⁎Corresponding author. anilkumardurg1996@gmail.com (Anil Kumar)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

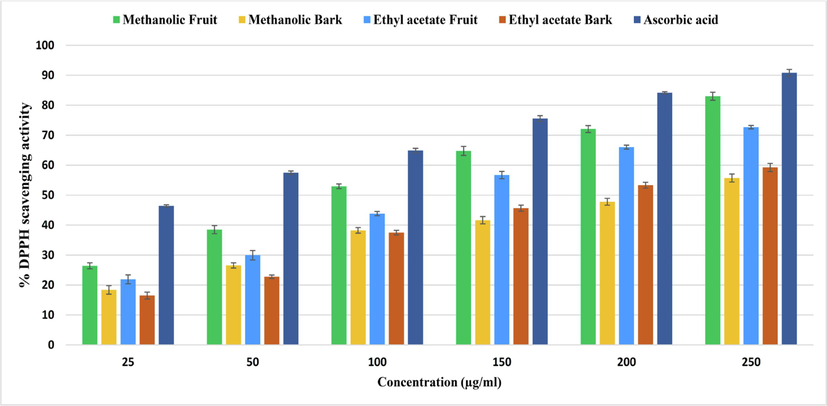

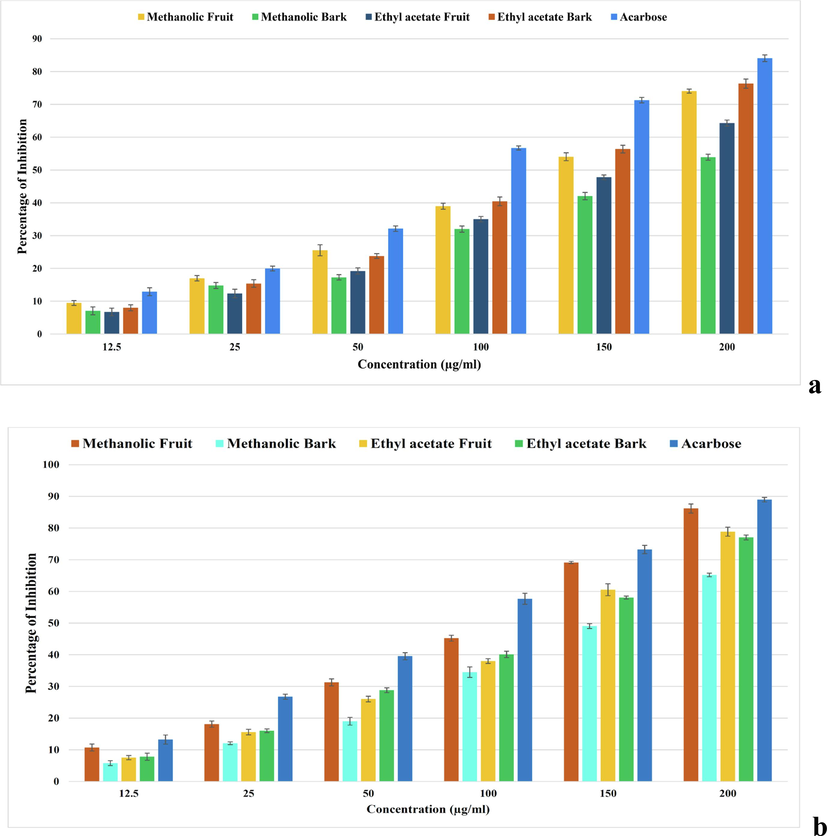

Bridelia retusa is a medicinal plant widely used to treat diabetes by ethnic populations worldwide, has been subjected to GC–MS-based profiling for the bark and fruit and identified 96 phytochemicals using ethyl acetate and methanol solvents. The DPPH antioxidant assay recorded that methanolic fruit extract had a maximum antioxidant activity of 83.01 % (IC50-103.03 µg/ml). The α-amylase inhibition activity was found maximum in ethyl acetate bark extract with 76.34 % (127.37 µg/ml), while methanolic fruit extract exhibited the highest α-glucosidase inhibition activity with 86.18 % (106.15 µg/ml). Subsequently, we have compared the antidiabetic potential for 3 pharmacologically significant bioactive constituents friedelin, imidazole & sylvestrene through docking and drug likeliness study and found friedelin has a maximum binding affinity with different protein targets followed by sylvestrene and is most suitable candidate for drug development for hyperglycemia. Molecular dynamics simulations revealed friedelin as the most stable binder to anti-diabetic target proteins, with notable structural insights provided by RMSD, RMSF, SASA, and PCA analyses. MM-PBSA calculations emphasized the significance of various energies with the α-amylase-Friedelin complex exhibiting the highest binding energy.

Keywords

Bridelia retusa

Antioxidants

Antidiabetic

GC–MS

Molecular docking

1 Introduction

Medicinal plants contain abundant bioactive compounds with therapeutic potential. Although many phytoconstituents are identified in nature, only a few are isolated and studied for their bioactivity. Comprehensive phytochemical screening is crucial for discovering and developing effective medicinal agents with well-defined profiles.

Traditional healers practice B. retusa to treat various ailments, including diabetes, jaundice, and infections (Tatiya et al., 2011; Ghawate et al., 2014; Ngueyem et al., 2009; Rupali et al., 2016). Despite its traditional use, there is a lack of scientific validation regarding its free radical scavenging capacity, anti-hyperglycemic activity, and receptor binding. The pharmaceutical industry faces challenges with drug development due to poor pharmacokinetic properties and inadequate receptor interactions, leading to financial losses. Molecular docking approaches are now employed to explore plant-based molecules for drug design and testing, offering valuable insights into binding interactions between drug candidates and target proteins (Konappa et al., 2020; Loza-Mejía et al., 2018; Lee and Kim, 2019).

Therefore, the present study aims at qualitative phytochemical analysis, antioxidative and anti-hyperglycaemic evaluation for B. retusa, along with, in silico validation of the potential bioactive phytocompounds to examine antidiabetic (e.g., α-amylase, α-glucosidase & DPP-IV) potential.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Identification, and authentication

The specimen was collected from Durg, Chhattisgarh, India, in April 2021 (Fig. S1) and authenticated as B. retusa (L.) A.Juss. by BSI, Allahabad, India. The voucher number I (B.S.I/C.R.C. 2020–21/200) was assigned and deposited at BSI, Allahabad.

2.2 Extraction and phytochemical screening

The bark and fruit of B. retusa were cleaned, powdered, and extracted with methanol and ethyl acetate using a Soxhlet extractor at 50–80 °C for 5–10 h. The extracts were filtered and analyzed for bioactive compounds, confirming the presence of alkaloids, cardiac glycosides, flavonoids, saponins, tannins, steroids, and terpenoids.

2.3 Phytochemical analysis by GC–MS

The samples were dissolved in methanol and ethyl acetate and injected into a Shimadzu® GC–MS QP2010 with a SH-I-5Sil MS Capillary column (30 m x 0.25 mm x 0.25 µm) in splitless mode. The oven temperature was set at 45 °C for 2 min, increased to 140 °C at 5 °C/min, then raised to 280 °C and held for 10 min. The injection volume was 2 µL, with helium at 1 mL/min flow rate and 70 eV ionization. The run time was 9.10 to 52.0 min. Compounds were identified by matching mass fragmentation patterns with the NIST 14. L library (Mallard and Linstrom, 2008).

2.4 Antioxidant activity

The DPPH assay, following Karamian et al. (2014), was used to estimate the free radical scavenging ability of B. retusa extracts. Solutions of the extracts (25–250 µg/ml) were mixed with 0.004 % methanolic DPPH, and incubated in the dark at 36 °C for 30 min, and their absorbance was recorded at 517 nm. A blank solution with methanol and DPPH was used as a control, with ascorbic acid as a reference. The IC50 was calculated from the calibration curve using the linear regression equation. where A con– absorption of the control,

A test- absorbance with samples of the extracts.

2.5 Antidiabetic activity

The α-amylase inhibition assay for B. retusa fruit and bark extracts were determined by useing the 3,5-dinitro salicylic acid method, with acarbose as a control. Absorbance was measured at 540 nm. The α-glucosidase inhibition assay was measured followed by Eom et al., (2012), with IC50 calculated, both using acarbose as a standard.

2.6 Molecular docking

Friedelin, imidazole, and sylvestrene were selected for antidiabetic profiling via molecular docking, based on GC–MS analysis and literature. Their 3D structures were retrieved from PubChem, converted to PDFs using Open Babel, and were used for docking studies with diabetes-related target proteins: DPP-IV (PDB: 4A5S), α-amylase (PDB: 5KEZ), and α-glucosidase (PDB: 1UOK). Protein-ligand interactions were analyzed using UCSF Chimera, with the best binding poses determined by the lowest binding free energy. Drug-likeness was evaluated using SWISSADME, adhering to Lipinski's rule of five (Daina and Zoete, 2016; Kurjogi et al., 2018).

2.7 Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation of protein-ligand complexes

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation was performed to assess the time-dependent stability of friedelin, imidazole, and sylvestrene complexed with DPP-IV (PDB: 4A5S), α-amylase (PDB: 5KEZ), and α-glucosidase (PDB: 1UOK). Using GROMACS-2022 with the CHARMM36 force field, ligand topology files were generated via the CGenFF server, and protein topology files through pdb2gmx. The complexes were energy-minimized and equilibrated, followed by a 100 ns MD run. Trajectories were analyzed for RMSD, RMSF, Rg, hydrogen bonds, SASA, and PCA, with the Free Energy Landscape (FEL) visualized in 2D and 3D (Hess et al., 1997; Van Der Spoel et al., 2005; Vanommeslaeghe et al., 2010; Huang and MacKerell, 2013).

2.8 ΔGBind calculations through MM-PBSA for protein–ligand complex

The binding-free energy (ΔGBind) of protein–ligand complexes (DPP-IV, α-amylase, α-glucosidase) with friedelin, imidazole, and sylvestrene were calculated using the MM-PBSA method in GROMACS. This analysis, based on trajectories from the last 10 ns of MD simulation, helps evaluation of interaction energy, conformational changes, and entropy's role in binding affinity (Van Der Spoel et al., 2005). where, ΔGbind is the total free energy of the protein–ligand complex and ΔGReceptor and ΔGLigand are the total free energies of the separated protein and ligand in a solvent, respectively.

2.9 Statistical analysis

The experiments were conducted in triplicate (n = 3), and the data were presented as the mean ± standard deviation. The IC50 values were determined and calculated using linear regression analysis with the aid of Microsoft Excel 2016 software.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Phytochemical screening

GC–MS analysis of B. retusa extracts identified 96 peaks, revealing 34 compounds in methanol fruit and 38 in ethyl acetate fruit extracts. Additionally, 12 compounds from methanolic bark and 29 from ethyl acetate bark were recorded. These phytocompounds, detailed in (Table S1 to S6 & Fig. S2–S5) underscore the plant's therapeutic significance.

Tatiya et al., (2017) identified friedelin, β-sitosterol, stigmasterol, and lupeol in B. retusa bark with applications for pain and arthritis. Chitosan flavonoid was noted for analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects. Adhav et al., (2002) reported isoflavone with antiviral properties, and Kumar and Jain (2014) confirmed β-sitosterol, ellagic acid, and gallic acid as antifungal, antibacterial, and antioxidant. Additional compounds such as bisabolene sesquiterpenes, various benzoic acids, and sesamin were identified by Jayasinghe et al., (2003) and Umar et al., (2022), with potential SARS-CoV-2 inhibition. Ogbonnia et al. (2021) described other compounds in Bridelia ferruginea. Present study provides a comprehensive description of 92 compounds from B. retusa, with 88 as newly reported.

3.2 Antioxidant activity

In the DPPH assay, the ability of the extracts to donate hydrogen atoms or electrons was assessed, leading to DPPH% reduction to DPPH-H. The IC50 values were determined from calibration curves and compared to ascorbic acid. The methanolic fruit extract of B. retusa showed the highest DPPH scavenging activity at 83.01 % and an IC50 of 103.03 µg/ml. It was followed by the ethyl acetate fruit extract (IC50: 135.66 µg/ml), ethyl acetate bark extract (IC50: 185.8 µg/ml), and methanolic bark extract (IC50: 206.72 µg/ml). In a similar study, the scavenging activity was reported as follows: ascorbic acid > aqueous extract > ethanol extract > methanol extract > 50 % ethanol extract > 50 % methanol extract > 70 % acetone extract, with IC50 values of 58.78 %, 62.61 %, 62.27 %, 61.94 %, 62.61 %, 70.46 %, and 61.93 %, respectively. (Tatiya et al., 2011). Murukan et al., (2018) reported that purified anthocyanin from B. retusa exhibited significant DPPH scavenging activity with an IC50 of 0.31 mg/ml, ABTS+scavenging activity with an IC50 of 0.55 mg/ml, and a high ferric-reducing capability (414.5 μmol Fe (II)/mg). Sanseera et al., (2016) found that chloroform, hexane, and methanol extracts of B. retusa demonstrated notable DPPH and ABTS scavenging activities. The methanol extracts of leaves, stems, and fruits had IC50 values of 0.52 ± 0.031 mg/mL, 0.12 ± 0.003 mg/mL, and 0.17 ± 0.005 mg/mL for DPPH, and 0.67 ± 0.007 mg/mL, 1.41 ± 0.001 mg/mL, and 5.58 ± 0.009 mg/mL for ABTS. Ogbonnia et al. (2021) noted that various solvent fractions of Bridelia ferruginea showed higher antioxidant activities compared to the crude extract.

Our finding is affirmative to previous findings by some authors. Still, the contribution of our study is GC–MS-based recognition of a wide spectrum of phytocompounds from B. retusa which strongly supports the therapeutic application of the plant by traditional healers worldwide.

3.3 Antidiabetic activity

In the α-amylase inhibition assay, ethyl acetate bark extract showed the highest inhibition at 76.34 %. This was followed by methanolic fruit extract (74.05 % at 130.97 µg/ml), ethyl acetate fruit extract (64.31 % at 153.36 µg/ml), and methanolic bark extract (53.89 % at 181.7 µg/ml) whereas, acarbose, the standard, achieved 84.07 % inhibition (99.52 µg/ml). These results suggest the potential of B. retusa extract for antihyperglycemic activity, making it a candidate for managing hyperglycemia by inhibiting α-amylase, which can reduce post-meal blood glucose spikes (Lordan et al., 2013) (Fig. 1).

showing antioxidant activity of B. retusa fruit and bark extract through DPPH radical scavenging activity.

In the α-glucosidase enzyme inhibition assay we found a dose-dependent inhibition activity with standard drug acarbose. The methanolic fruit extract of B. retusa exhibited maximum α-glucosidase inhibition activity with 86.18 % (106.15 μg/ml), followed by the ethyl acetate fruit extract with 78.87 % (122.93 μg/ml), ethyl acetate bark extract 77.04 % (124.01 μg/ml) and methanolic bark extract 65.20 % (151.24 μg/ml). While the standard drug acarbose revealed α-glucosidase inhibition of 88.96 % (89.85 μg/ml) (Fig. 2).

showing antidiabetic enzymes activities of B. retusa fruit and bark extracts. (a) α-amylase inhibition activity, (b) α-glucosidase inhibition activity.

Pancreatic α-amylase and α-glucosidase enzymes break down starches and sugars into monosaccharides, crucial for glucose absorption (Ochieng et al., 2017). Inhibiting α-glucosidase can delay glucose absorption and reduce postprandial hyperglycemia, as seen with medications like acarbose and voglibose (Matsui et al., 1996). Our study found that ethyl acetate bark extract and methanolic fruit extract of B. retusa effectively inhibited α-amylase and α-glucosidase, respectively, supporting its traditional use for diabetes management.

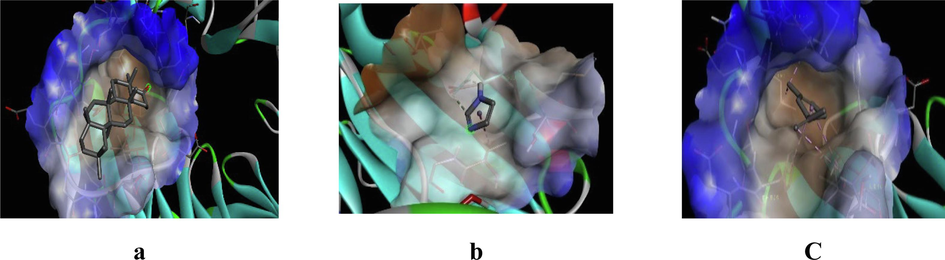

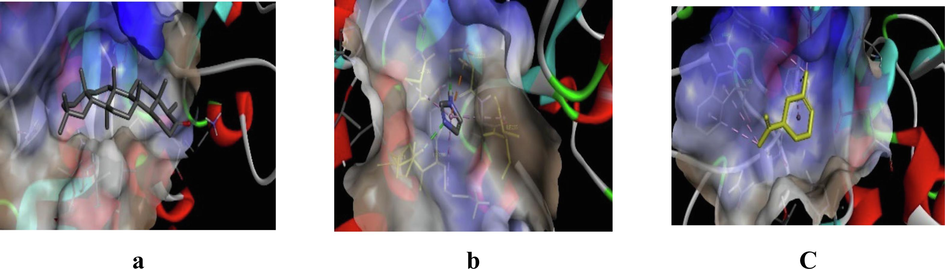

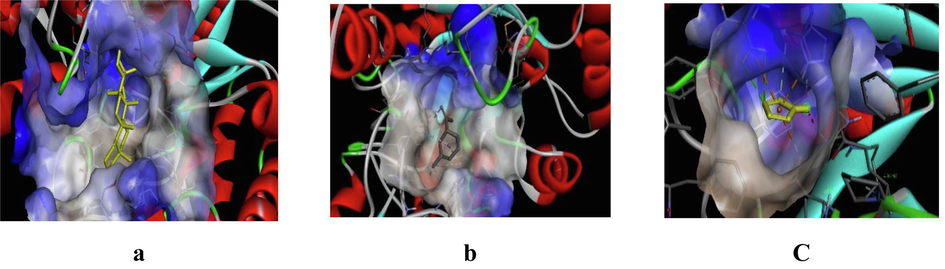

3.4 Molecular docking

GC–MS analysis of B. retusa bark and fruit extracts identified 96 bioactive compounds (Table 1). For molecular docking, friedelin, imidazole, and sylvestrene were selected for interaction with three target proteins. Friedelin showed the most favorable binding with DPP-IV (−9.3 kcal/mol), α-amylase (−9.8 kcal/mol), and α-glucosidase (−10.3 kcal/mol), indicating superior binding affinity compared to imidazole and sylvestrene. Imidazole had the lowest affinity with binding energies of −3.6 kcal/mol, −2.7 kcal/mol, and −3.3 kcal/mol for DPP-IV, α-amylase, and α-glucosidase, respectively. Sylvestrene also showed better affinity than imidazole but less than friedelin (Table 2, 3; Figs. 3-5, Fig. S6-S8).

S. No.

Retention time

Name of the compound

Structure

RT-2.156

Furfural

C1=COC(=C1)C=O

RT-3.050

Glycerin

C(C(CO)O)O

RT-3.795

Pyrovalerone

CCCC(C(=O)C1 = CC=C(C=C1)C)N2CCCC2

RT-4.339

Pyranone

C1=CC(=O)OC=C1

RT-5.252

Hydroxymethylfurfural

C1=C(OC(=C1)C=O)CO

RT-6.028

3-Octanol, 2,6-dimethyl-, acetate

CCC(C)CCC(C(C)C)OC(=O)C

RT-6.785

1,4-Dioxane, 2-ethyl-5-methyl-

CCC1COC(CO1)C

RT-7.091

Pyrogallol

C1=CC(=C(C(=C1)O)O)O

RT-7.542

D-Allose

C([C@@H]1[C@H]([C@H]([C@H](C(O1)O)O)O)O)O

RT-8.236

α-D-Galactopyranoside, methyl

O1[C@H](OC)[C@H](O)[C@@H](O)[C@@H](O)[C@H]1CO

RT-8.624

d-Mannose

C([C@@H]1[C@H]([C@@H]([C@@H](C(O1)O)O)O)O)O

RT-8.886

Tetradecanoic acid

CCCCCCCCCCCCCC(=O)O

RT-9.331

3-O-Methyl-d-glucose

CO[C@H]([C@H](C=O)O)[C@@H]([C@@H](CO)O)O

RT-10.425

Hexadecanoic acid, methyl ester

CCCCCCCCCCCCCCCC(=O)OC

RT-10.782

Benzenepropanoic acid, 3,5-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)-4-hydroxy-, methyl ester

CC(C)(C)C1=CC(=CC(=C1O)C(C)(C)C)CCC(=O)OC

RT-11.120

n-Hexadecanoic acid

CCCCCCCCCCCCCCCC(=O)O

RT-11.676

Isopropyl palmitate

CCCCCCCCCCCCCCCC(=O)OC(C)C

RT-12.552

Heptanoic acid, 4-octyl ester

CCCCCCC(=O)OC(CCC)CCCC

RT-12.796

9,12-Octadecadienoic acid, methyl ester

CCCCC/C=C\C/C=C\CCCCCCCC(=O)OC

RT-12.877

Methyl petroselinate

CCCCCCCCCCC/C=C\CCCCC(=O)OC

RT-13.121

Phytol

C[C@@H](CCC[C@@H](C)CCC/C(=C/CO)/C)CCCC(C)C

RT-13.259

Heptadecanoic acid, 16-methyl-, methyl ester

CC(C)CCCCCCCCCCCCCCC(=O)OC

RT-13.897

Linoleic acid

CCCCC/C=C\C/C=C\CCCCCCCC(=O)O

RT-14.166

Octadecanoic acid

CCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCC(=O)O

RT-17.913

Eicosanoic acid (Arachidic acid)

[2H]C([2H])([2H])CCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCC(=O)O

RT-19.902

Hexanoic acid, 2-ethyl-, hexadecyl ester

CCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCOC(=O)C(CC)CCCC

RT-20.328

Hexadecanoic acid, 2-(octadecyloxy)ethyl ester

CCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCOCCOC(=O)CCCCCCCCCCCCCCC

RT-21.110

Hexadecanoic acid, 2-hydroxy-1-(hydroxymethyl)ethyl ester

CCCCCCCCCCCCCCCC(=O)OC(CO)CO

RT-21.560

Diisooctyl phthalate

CC(C)CCCCCOC(=O)C1 = CC=CC=C1C(=O)OCCCCCC(C)C

RT-24.256

Hexanoic acid, 2-ethyl-, octadecyl ester

CCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCOC(=O)C(CC)CCCC

RT-26.839

Erucylamide

CCCCCCCC/C=C\CCCCCCCCCCCC(=O)N

RT-27.503

Squalene

CC(=CCC/C(=C/CC/C(=C/CC/C=C(/CC/C=C(/CCC=C(C)C)\C)\C)/C)/C)C

RT-31.362

Rhodopin

CC(=CCC/C(=C/C=C/C(=C/C=C/C(=C/C=C/C=C(\C)/C=C/C=C(\C)/C=C/C=C(\C)/CCCC(C)(C)O)/C)/C)/C)C

RT-32.926

Friedelin

C[C@H]1C(=O)CC[C@@H]2[C@@]1(CC[C@H]3[C@]2(CC[C@@]4([C@@]3(CC[C@@]5([C@H]4CC(CC5)(C)C)C)C)C)C)C

RT-2.617

Ethyl Acetate

CCOC(=O)C

RT-4.550

Propyl acetate

CCCOC(=O)C

RT-11.238

trans-Chrysanthenyl acetate

CC1 = CC[C@H]2[C@H]([C@@H]1C2(C)C)OC(=O)C

RT-21.740

1-Undecanol

CCCCCCCCCCCO

RT-25.209

Dodecanoic acid, 10-methyl-, methyl ester

CCC(C)CCCCCCCCC(=O)OC

RT-27.898

Dioctyl terephthalate

CCCCCCCCOC(=O)C1 = CC=C(C=C1)C(=O)OCCCCCCCC

RT-29.103

Dodecyl acrylate

CCCCCCCCCCCCOC(=O)C=C

RT-34.731

Terephthalic acid, 4-octyl octyl ester

CCCCCCCCOC(=O)C1 = CC=C(C=C1)C(=O)OC(CCC)CCCC

RT-37.234

Methyl octadeca-9,12-dienoate

CCCCCC=CCC=CCCCCCCCC(=O)OC

RT-37.340

trans-13-Octadecenoic acid, methyl ester

CCCC/C=C/CCCCCCCCCCCC(=O)OC

RT-37.804

Methyl stearate

CCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCC(=O)OC

RT-42.505

Hexanedioic acid, bis(2-ethylhexyl) ester

CCCCC(CC)COC(=O)CCCCC(=O)OCC(CC)CCCC

RT-3.163

Tridecane

CCCCCCCCCCCCC

RT-3.569

Octane, 5-ethyl-2-methyl-

CCCC(CC)CCC(C)C

RT-4.389

2-Dodecene, (Z)-

CCCCCCCCC/C=C\C

RT-5.146

Dodecane, 2,6,11-trimethyl-

CC(C)CCCCC(C)CCCC(C)C

RT-5.265

Pentadecane

CCCCCCCCCCCCCCC

RT-5.327

Dodecane, 5,8-diethyl-

CCCCC(CC)CCC(CC)CCCC

RT-5.665

Undecane, 4,7-dimethyl-

CCCCC(C)CCC(C)CCC

RT-5.728

Hexane, 3,3-dimethyl-

CCCC(C)(C)CC

RT-6.034

Cetene

CCCCCCCCCCCCCCC=C

RT-6.766

Hexadecane

CCCCCCCCCCCCCCCC

RT-7.060

Hexadecane, 2,6,11,15-tetramethyl-

CC(C)CCCC(C)CCCCC(C)CCCC(C)C

RT-7.129

Disulfide, di-tert-dodecyl

CCCCCCCCCC(C)(C)SSC(C)(C)CCCCCCCCC

RT-7.273

Heptadecane, 2,6,10,15-tetramethyl-

CCC(C)CCCCC(C)CCCC(C)CCCC(C)C

RT-8.286

Eicosane, 2-methyl-

CCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCC(C)C

RT-8.549

Eutanol G

CCCCCCCCCCC(CCCCCCCC)CO

RT-8.799

Heptadecane, 3-methyl-

CCCCCCCCCCCCCCC(C)CC

RT-8.861

2-Octadecoxyethanol

CCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCOCCO

RT-8.905

Octadecanoic acid, 4-hydroxy-, methyl ester

CCCCCCCCCCCCCCC(CCC(=O)OC)O

RT-9.005

Hexadecen-1-ol, trans-9-

CCCCCC/C=C/CCCCCCCCO

RT-9.931

Cyclopropaneoctanoic acid, 2-[(2-pentylcyclopropyl)methyl]-, methyl ester, trans,trans-

CCCCC[C@@H]1CC1CC2C[C@H]2CCCCCCCC(=O)OC

RT-10.432

Hexadecanoic acid, methyl ester or Methyl palmitate

CCCCCCCCCCCCCCCC(=O)OC

RT-10.619

7,9-Di-tert-butyl-1-oxaspiro(4,5)deca-6,9-diene-2,8-dione

CC(C)(C)C1 = CC2(CCC(=O)O2)C=C(C1 = O)C(C)(C)C

RT-10.888

Eicosane, 7-hexyl-

CCCCCCCCCCCCCC(CCCCCC)CCCCCC

RT-11.245

2-Hexadecanol

CCCCCCCCCCCCCCC(C)O

RT-12.546

Heptanoic acid, anhydride

CCCCCCC(=O)OC(=O)CCCCCC

RT-12.796

8,11-Octadecadienoic acid, methyl ester

CCCCCC/C=C/C/C=C/CCCCCCC(=O)OC

RT-12.877

10-Octadecenoic acid, methyl ester

CCCCCCC/C=C/C(CCCCCCCC(=O)OC)O

RT-13.365

Octadecane, 3-ethyl-5-(2-ethylbutyl)-

CCCCCCCCCCCCCC(CC(CC)CC)CC(CC)CC

RT-14.347

10-Heneicosene (c,t)

CCCCCCCCCC/C=C/CCCCCCCCC

RT-18.201

Hexacosyl acetate

CCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCOC(=O)C

RT-29.091

Tetratriacontane

CCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCC

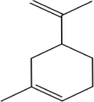

RT-3.292

Isobutyl acetate

CC(C)COC(=O)C

RT-9.442

3-Carene

CC1 = CCC2C(C1)C2(C)C

RT-10.136

Sylvestrene

CC1 = CCC[C@H](C1)C(=C)C

RT-10.537

1-Hexanol, 2-ethyl-

CCCCC(CC)CO

RT-12.059

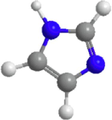

Imidazole

C1 = CN=CN1

RT-17.198

2,4-Imidazolidinedione, 3-methyl-

CN1C(=O)CNC1 = O

RT-23.895

Tromethamine

C(C(CO)(CO)N)O

RT-25.977

10-Methylnonadecane

CCCCCCCCCC(C)CCCCCCCCC

RT-27.353

Crocetane

CC(C)CCCC(C)CCCCC(C)CCCC(C)C

RT-32.041

3-Chloropropionic acid, heptadecyl ester

CCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCOC(=O)CCCl

RT-33.247

1-Dodecanol, 2-hexyl-

CCCCCCCCCCC(CCCCCC)CO

RT-33.782

Trichloroacetic acid, hexadecyl ester

CCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCOC(=O)C(Cl)(Cl)Cl

RT-34.671

2-Isopropyl-5-methyl-1-heptanol

CCC(C)CCC(CO)C(C)C

RT-36.072

1,4-Benzenedicarboxylic acid, bis(2-ethylhexyl) ester

CCCCC(CC)COC(=O)C1 = CC=C(C=C1)C(=O)OCC(CC)CCCC

RT-40.224

Terephthalic acid, 3-hexyl octyl ester

CCCCCCCCOC(=O)C1=CC=C(C=C1)C(=O)OC(CC)CCC

RT-43.511

Ethanol, 2-(octadecyloxy)-

CCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCOCCO

RT-41.661

Decanedioic acid, dibutyl ester

CCCCOC(=O)CCCCCCCCC(=O)OCCCC

RT-44.047

2-Methyl-Z-4-tetradecene

CCCCCCCCC/C=C\CC(C)C

RT-45.131

Heptacosyl pentafluoropropionate

CCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCOC(=O)C(C(F)(F)F)(F)F

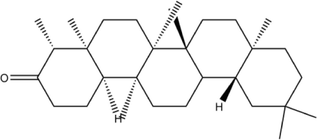

S. No.

Drug-likeness properties

Friedelin

Sylvestrene

Imidazole

3D structure

2D structure

Molecular formula

C30H50O

C10H16

C3H4N2

Molecular weight

426.7

136.23

68.08

LogP

9.8

3.4

−0.1

H-bond Acceptor

1

0

1

H-bond Donor

0

0

1

Rotatable Bond

0

1

0

Topological Polar Surface Area

17.1\AA2

0\AA2

28.7\AA2

Heavy atom

31

10

5

S. No.

Ligand name

PubChem ID

Docking

DPP-IV

α-amylase

α-glucosidase

1

Friedelin

91472

Score (kcal/mol)

−9.3

−9.8

−10.3

Interacting residues

Lys71, Asn74. Ile76, Leu90, Asn92, Phe95, Asp96, Phe98, His100, Ser101, Ile102, Tyr105

Gln63, Tyr151, Leu162, Thr163, Leu165, Lys200, His201, Glu233, Ile235, Asp300

Gly141, Ala142, Ala143, Leu162, Phe163, Phe203, Ser222, Gly223, His224, Phe227, Met228, Pro257, Phe281, Met284, Asp285, Lys293, Asp329, Gln330, Glu387, Lys413

2

Imidazole

795

Score (kcal/mol)

−3.6

−2.7

−3.3

Interacting residues

Glu347, Met348, Ser349, Val354, Gly355, Ile375

Ala198, Ser199, Lys200, His201, Glu233, Val234

Asp60, Tyr63, Phe163, Arg197, Asp199, Val200, Glu255, His328, Asp329, Arg415

3

Sylvestrene

12304570

Score (kcal/mol)

−6.4

−5.7

−5.3

Interacting residues

Lys71, Ile76, Glu91, Phe95, Ile102, Tyr105, Ile114, Leu116 Asn75, Leu90, Asn92, Asn74

Trp58, Trp59, Tyr62, Gln63, His101, Leu165, Asp197, His299, Asp300

Ala143, Leu162, Phe163, Val200, Phe203, His224, Phe227, Met228, Pro257

3D representation of best possible pose(s) of ligands- (a) friedelin, (b) imidazole, (c) sylvestrene within the active site of the target molecule (DPP-IV).

3D representation of best possible pose(s) of ligands- (a) friedelin, (b) imidazole, (c) sylvestrene within the active site of the target molecule (α-amylase).

3D representation of best possible pose(s) of ligands- (a) friedelin, (b) imidazole, (c) sylvestrene within the active site of the target molecule (α-glucosidase).

Friedelin interacted with 12 residues in DPP-IV (Lys71, Asn74, Ile76, Leu90, Asn92, Phe95, Asp96, Phe98, His100, Ser101, Ile102, Tyr105), 10 in α-amylase (Gln63, Tyr151, Leu162, Thr163, Leu165, Lys200, His201, Glu233, Ile235, Asp300), and 20 in α-glucosidase (Gly141, Ala142, Ala143, Leu162, Phe163, Phe203, Ser222, Gly223, His224, Phe227, Met228, Pro257, Phe281, Met284, Asp285, Lys293, Asp329, Gln330, Glu387, Lys413). Imidazole interacted with 6 residues in DPP-IV (Glu347, Met348, Ser349, Val354, Gly355, Ile375), 6 in α-amylase (Ala198, Ser199, Lys200, His201, Glu233, Val234), and 10 in α-glucosidase (Asp60, Tyr63, Phe163, Arg197, Asp199, Val200, Glu255, His328, Asp329, Arg415). Sylvestrene interacted with 12 residues in DPP-IV (Lys71, Ile76, Glu91, Phe95, Ile102, Tyr105, Ile114, Leu116, Asn75, Leu90, Asn92, Asn74), 9 in α-amylase (Trp58, Trp59, Tyr62, Gln63, His101, Leu165, Asp197, His299, Asp300), and 9 in α-glucosidase (Ala143, Leu162, Phe163, Val200, Phe203, His224, Phe227, Met228, Pro257).

Our investigation shows that the phytocompounds friedelin, imidazole, and sylvestrene from B. retusa significantly inhibit α-glucosidase, α-amylase, and DPP-IV. This suggests extract of B. retusa could aid in glucose control by slowing glucose release and improving blood sugar regulation. Molecular docking highlights friedelin as a promising candidate for developing new antidiabetic inhibitors targeting these enzymes.

Dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP-IV) inactivates glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP), key incretin hormones. Inhibiting DPP-IV can help to regulate glucose levels in diabetes. α-Amylase, a calcium metalloenzyme, also contributes to elevated postprandial blood glucose and is a target for diabetes management (Kaur et al., 2021). Smruthi et al., (2016) found that phytocompounds from Syzygium cumini (e.g., friedelin, beta-sitosterol) interact with α-amylase with lower binding energies than acarbose. Similarly, compounds from other plants (e.g., 6 urs-12-en-24-oic acid from P. zeylanica) showed strong binding with DPP-IV and α-amylase, suggesting high potential for managing diabetes (Thamaraiselvi et al., 2021).

For α-glucosidase and α-amylase, compounds like acarbose and epigallocatechin gallate showed varying inhibitory activities, with epigallocatechin gallate as notable (Oboh et al., 2014; Tadera et al., 2006). Docking of amentoflavone, friedelin, and 6-deoxyjacareubin with porcine pancreatic elastase yielded binding energies of −10.94, −7.17, and −6.72 kcal/mol, respectively, with friedelin showing strong interactions, including a Pi-sigma bond with His57 (Ambarwati et al., 2022). Muralikrishna et al. (2019) found that beta-sitosterol and friedelin from Ficus racemose had favorable interactions with hyperglycemic targets, with friedelin forming hydrogen bonds with Lys776. Drug-likeness properties of B. retusa compounds were assessed using SwissADME based on Lipinski’s rule of five (Daina and Zoete, 2016).

Sylvestrene and imidazole met all Lipinski criteria viz. molecular weight (≤500), hydrogen bond acceptors (≤10), donors (≤5), and LogP (<5). However, friedelin exceeded the LogP threshold, indicating high lipophilicity and potential issues with absorption (Bahmani et al., 2017). Despite this, all compounds showed favorable molecular weight and TPSA values, suggesting good absorption and permeability. Friedelin, along with sylvestrene and imidazole, exhibited promising antioxidant and antidiabetic activities, with friedelin standing out as the most effective candidate for diabetes therapy.

3.5 Molecular docking simulation analysis

MD simulations provide insights into protein–ligand interactions and ligand stability. We analyzed nine complexes: DPP-IV-Sylvestrene, DPP-IV-Imidazole, DPP-IV-Friedelin, α-amylase-Sylvestrene, α-amylase-Imidazole, α-amylase-Friedelin, α-glucosidase-Sylvestrene, α-glucosidase-Imidazole, and α-glucosidase-Friedelin (Fig. S9–S11). For stability assessment, RMSD and RMSF were monitored. RMSD analysis (Fig. S9a–c) showed that DPP-IV-Sylvestrene had the most stable RMSD (0.2–0.3 nm), while DPP-IV-Imidazole and DPP-IV-Friedelin had higher deviations. The α-amylase-Friedelin complex was the most stable (0.15–0.25 nm) compared to the other α-amylase complexes. For α-glucosidase, α-glucosidase-Friedelin was the most stable, with RMSD values of 0.15–0.35 nm initially, decreasing to 0.27–0.33 nm later. Higher RMSF values were observed for the imidazole complex, indicating greater fluctuation compared to sylvestrene and friedelin (Fig. S9d–f).

Radius of gyration (Rg) analysis measures the compactness of protein–ligand complexes, reflecting structural stability and integrity. Elevated Rg values suggest decreased compactness and potential structural instability, while lower values indicate a more stable structure. For DPP-IV protein complexes, Rg values ranged from 2.7 to 2.8 nm for all three drugs (Fig. S10a). For α-amylase, Rg values were between 2.32 and 2.4 nm for all drugs (Fig. S10b). For α-glucosidase, Rg values ranged from 2.42 to 2.57 nm, with the α-glucosidase-Friedelin complex showing the lowest Rg values of 2.43 to 2.47 nm (Fig. S10c).

Intermolecular hydrogen bond (H-Bond) analysis was performed for DPP-IV, α-amylase, and α-glucosidase with sylvestrene, imidazole, and friedelin. For DPP-IV, imidazole formed a maximum of 2 hydrogen bonds during 40–50 ns and 80–90 ns, while friedelin formed 1 hydrogen bond from 1 to 93 ns but none later, and sylvestrene formed no hydrogen bonds (Fig. S10d). For α-amylase, no hydrogen bonds were observed with sylvestrene, and friedelin formed a few single bonds around 20–30 ns and 45 ns. The α-amylase-imidazole complex formed 3 hydrogen bonds initially and exhibited intermittent bonding throughout the simulation (Fig. S10e). For α-glucosidase, sylvestrene formed no hydrogen bonds. Friedelin and imidazole formed 1–3 hydrogen bonds intermittently during the simulation (Fig. S10e).

SASA analysis was performed to evaluate the protein surface area exposed to water, indicating the extent of drug interaction. For DPP-IV, SASA values ranged from 320 to 350 nm2 (Fig. S11a). For α-amylase, SASA values were lower, between 185 to 225 nm2 (Fig. S11b), suggesting a stronger drug interaction. For α-glucosidase, SASA values ranged from 230 to 270 nm2 (Fig. S11c). The lower SASA values for α-amylase indicate a more stable drug interaction due to reduced protein surface exposure to water.

PCA analysis was used to assess protein–ligand complex stability by examining eigenvector variances. For DPP-IV, the sylvestrene complex had the least variance, with eigenvector values ranging from −3 to 3 nm (Fig. S11d), compared to −20 to 20 nm for imidazole and −60 to 40 nm for friedelin. For α-amylase, eigenvector values were −27 to 15 nm (sylvestrene), −16 to 18 nm (imidazole), and −10 to 6 nm (friedelin) (Fig. S11e), with the α-amylase-friedelin complex showing the least conformational changes. For α-glucosidase, eigenvector values ranged from −27 to 30 nm (sylvestrene), −18 to 17 nm (imidazole), and −4 to 4 nm (friedelin) (Fig. S11f). The best PCA values were observed for the α-glucosidase-friedelin complex, followed by α-amylase-friedelin and DPP-IV-sylvestrene complexes.

3.6 Binding free energy calculations of top drugs complexed with anti-diabetic target proteins

MM-PBSA free energy calculations were performed on the complexes of sylvestrene, imidazole, and friedelin with DPP-IV, α-amylase, and α-glucosidase, using MD trajectories from the last 10 ns (90–100 ns). The analysis highlighted van der Waals, electrostatic, and polar solvation energies as key stabilizers (Table 4). The maximum ΔGBind values were −60.457 ± 11.215 kJ/mol for DPP-IV-sylvestrene, −114.467 ± 8.982 kJ/mol for α-amylase-friedelin, and −102.904 ± 15.329 kJ/mol for α-glucosidase-friedelin. Among these, the α-amylase-friedelin complex exhibited the highest ΔGBind.

Protein-Ligand Complex

Van der Waal Energy (kJ/mol)

Electrostatic Energy (kJ/mol)

Polar Solvation Energy (kJ/mol)

Binding Energy (kJ/mol)

DPP-IV-Sylvestrene

−100.509 +/- 6.778

−0.850 +/- 3.256

51.910 +/- 8.641

−60.457 +/- 11.215

DPP-IV-Imidazole

−60.457 +/- 11.215

−60.457 +/- 11.215

12.816 +/- 97.276

11.732 +/-

96.795

DPP-IV-Friedelin

−66.763 +/- 60.857

−16.233 +/- 21.324

41.508 +/- 89.146

−49.45 +/- 54.854

α-amylase-Sylvestrene

–33.493 +/- 18.505

−0.515 +/- 1.936

18.155 +/- 19.946

−21.229 +/- 28.937

α-amylase-Imidazole

−1.402 +/- 4.102

−0.305 +/- 3.357

−1.773 +/- 36.396

−3.694 +/- 36.136

α-amylase-Friedelin

−140.119 +/- 10.377

−0.521 +/- 1.631

42.387 +/- 5.526

−114.467 +/- 8.982

α-glucosidase-Sylvestrene

−62.842 +/- 8.486

−1.176 +/- 2.106

24.748 +/- 15.303

−48.116 +/- 16.377

α-glucosidase-Imidazole

−4.738 +/- 6.795

−3.351 +/- 12.650

20.483 +/- 73.965

11.342 +/- 74.759

α-glucosidase-Friedelin

−148.948 +/- 10.475

3.879 +/- 4.881

60.083 +/- 15.311

−102.904 +/- 15.329

Molecular dynamics simulations revealed stability and structural dynamics in nine protein–ligand complexes. Friedelin showed the most stable interactions with DPP-IV, α-amylase, and α-glucosidase, indicated by lower RMSD and RMSF values. SASA analysis highlighted strong interactions, particularly with α-amylase. PCA revealed distinct conformational changes for each complex. MM-PBSA calculations highlighted van der Waals, electrostatic, and polar solvation energies as key stabilizers, with the α-amylase-friedelin complex showing the highest binding energy.

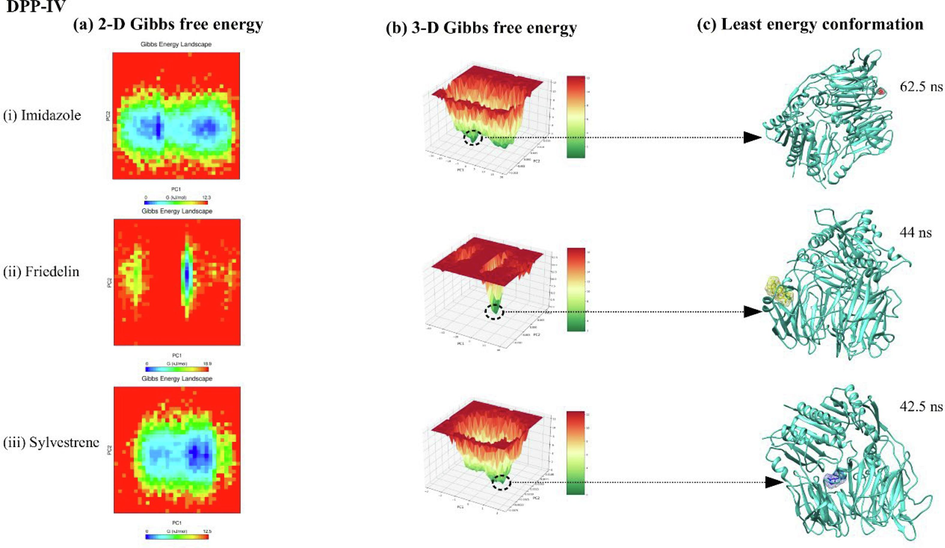

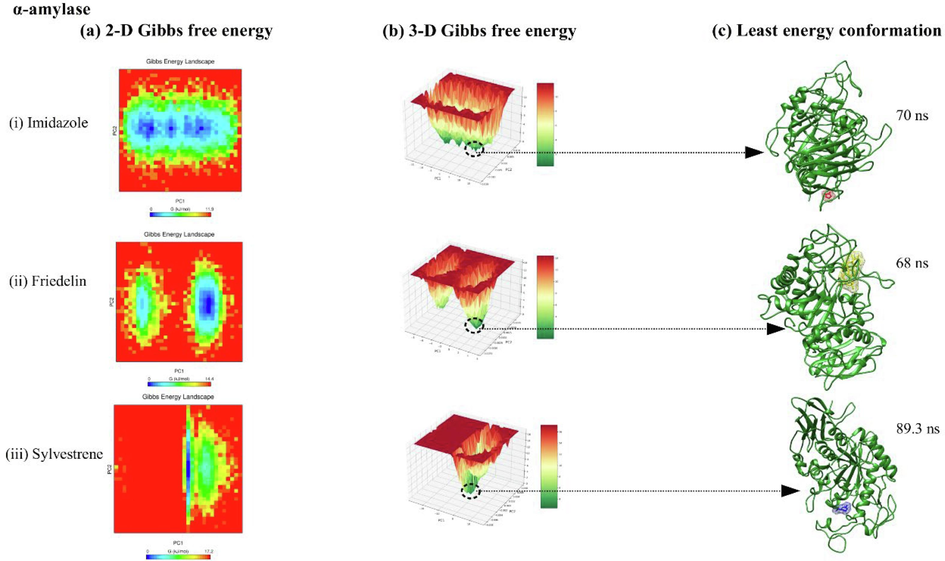

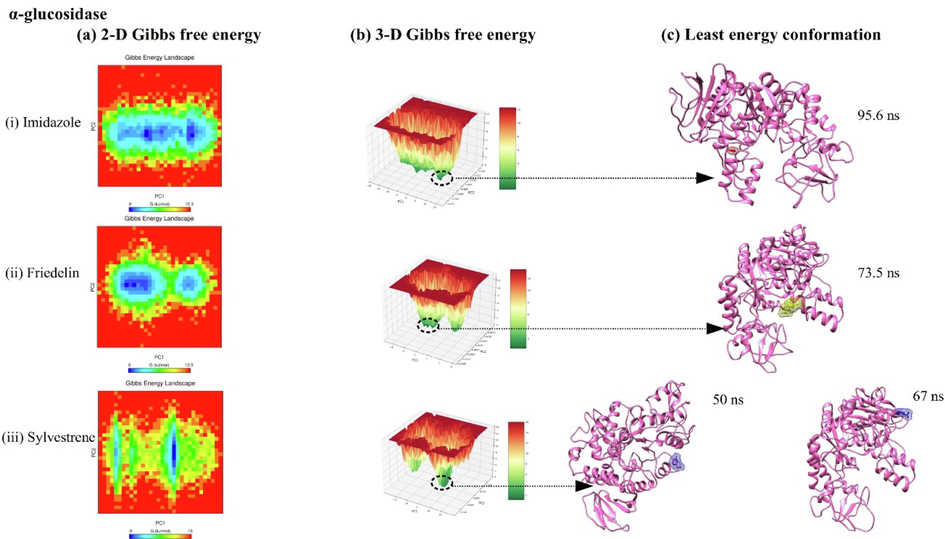

Free energy landscape (FEL) analysis for DPP-IV, α-amylase, and α-glucosidase complexes with imidazole, friedelin, and sylvestrene is shown in Figs. 6, 7, and 8. The 2D FEL plots (Fig. 6(a–b), 7(a–b), 8(a–b)) use red for maximum Gibbs free energy and blue for minimum Gibbs free energy, while the 3D FEL plots use red and dark green similarly. For DPP-IV, the least energy conformations occurred at 62.5 ns (imidazole), 44 ns (friedelin), and 42.5 ns (sylvestrene) (Fig. 6(c)). For α-amylase, they were at 70 ns (sylvestrene), 68 ns (imidazole), and 89.3 ns (friedelin) (Fig. 7(c)). For α-glucosidase, the least energy conformations were at 95.6 ns (imidazole), 73.5 ns (friedelin), and at 50 ns and 67 ns (sylvestrene) (Fig. 8(c)).

showing 2-D, 3-D principal component analysis along with free energy landscape plot for DPP-IV protein complexed with ligands imidazole, friedelin, and sylvestrene.

showing 2-D, 3-D principal component analysis along with free energy landscape plot for alpha-amylase protein complexed with ligands imidazole, friedelin, and sylvestrene.

showing 2-D, 3-D principal component analysis along with free energy landscape plot for alpha-glucosidase protein complexed with ligands imidazole, friedelin, and sylvestrene.

4 Conclusion

Diabetes remains a global challenge, with many relying on insulin. The scientific community seeks effective compounds to inhibit key regulatory receptors for diabetes control. We investigated B. retusa and identified promising compounds- sylvestrene, imidazole, and friedelin- known for their antioxidant properties and inhibition of α-amylase and α-glucosidase in in vitro. Molecular docking and drug-likeness studies support their potential. Based on antioxidant activity and in silico studies, we recommend Friedelin as the most promising candidate for drug development against diabetes.

Funding

The present study was supported by CSIR-India (Id: 08/526(0003)/2019-EMR-I) for Fellowship, and King Saud University under Researcher Supporting Project [RSPD2024R712].

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Somendra Kumar: Investigation. Dinesh Kumar: Validation. Motiram Sahu: Writing – original draft. Neha Shree Maurya: Data curation. Ashutosh Mani: Writing – review & editing. Chandramohan Govindasamy: Conceptualization. Anil Kumar: Supervision, Conceptualization.

Acknowledgement

The present study was supported by CSIR-India (Id.08/526(0003)/2019-EMR-1) for Fellowship, and also, this project was supported by Researchers Supporting Project number (RSPD2024R712), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Evaluation of isoflavanone as an antimicrobial agent from leaves of Bridelia retusa (L) Orient. J. Chem.. 2002;18:476-479.

- [Google Scholar]

- Molecular docking, physicochemical and drug-likeness properties of isolated compounds from Garcinia latissima Miq. on elastase enzyme: In silico analysis. Pharma. J.. 2022;14(2):282-288.

- [Google Scholar]

- A simple, robust, and efficient computational method for n-octanol/water partition coefficients of substituted aromatic drugs. Sci. Rep.. 2017;7(1):1-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- A BOILED-Egg to predict gastrointestinal absorption and brain penetration of small molecules. ChemMedChem. 2016;11:1117-1121.

- [Google Scholar]

- α-Glucosidase-and α-amylase-inhibitory activities of phlorotannins from Eisenia bicyclis. J. Sci. Food Agric.. 2012;92:2084-2090.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hepatoprotective activity of Bridelia retusa against paracetamol-induced liver damage in Swiss albino mice. Asian J. Biol. Sci.. 2014;7:217-224.

- [Google Scholar]

- LINCS: A linear constraint solver for molecular simulations. J. Comput. Chem.. 1997;18(12):1463-1472.

- [Google Scholar]

- CHARMM36 all-atom additive protein force field: Validation based on comparison to NMR data. J. Comput. Chem.. 2013;34(25):2135-2145.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antifungal constituent of the stem bark of Bridelia retusa. Phytochemistry. 2003;62:637-641.

- [Google Scholar]

- Essential oil composition and antioxidant activity of the methanol extracts of three Phlomis species from Iran. J. Biol. Active Products Nat.. 2014;4(5–6):343-353.

- [Google Scholar]

- Alpha-amylase as a molecular target for the treatment of diabetes mellitus: A comprehensive review. Chem. Biol. Drug Des.. 2021;98(4):539-560.

- [Google Scholar]

- GC-MS analysis of phytoconstituents from Amomum nilgiricum and molecular docking interactions of bioactive serverogenin acetate with target proteins. Sci. Rep.. 2020;10(1):16438.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory activities of Bridelia retusa methanolic fruit extract in experimental animals. Scient. World J.. 2014;2014:890151

- [Google Scholar]

- Computational modeling of the staphylococcal enterotoxins and their interaction with natural antitoxin compounds. Int. J. Mol. Sci.. 2018;19(1):133.

- [Google Scholar]

- In-silico molecular binding prediction for human drug targets using deep neural multi-task learning. Genes. 2019;10:906.

- [Google Scholar]

- The α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitory effects of Irish seaweed extracts. Food Chem.. 2013;141(3):2170-2176.

- [Google Scholar]

- In silico studies on compounds derived from Calceolaria: phenylethanoid glycosides as potential multitarget inhibitors for the development of pesticides. Biomolecules. 2018;8:121.

- [Google Scholar]

- NIST Standard Reference Database. National Institute of Standards and Technology; 2008.

- In vitro survey of alpha-glucosidase inhibitory food components. Biosci. Biotech. Bioch.. 1996;60(12):2019-2022.

- [Google Scholar]

- In silico docking and in vitro enzyme inhibition activity of unripe fruits of Ficus racemosa Linn. Eur. J. Pharm. Med. Res.. 2019;5(6)

- [Google Scholar]

- Purified anthocyanin from Bridelia retusa (L.) Spreng. as antioxidant and antimicrobial: A medicinal plant from South Western Ghats, Kerala. Int. J. Pharm. Res. Health Sci.. 2018;6:2250-2257.

- [Google Scholar]

- The genus Bridelia: A phytochemical and ethnopharmacological review. J. Ethnopharmacol.. 2009;124:339-349.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparative effect of quercetin and rutin on α-amylase, α-glucosidase, and some pro-oxidant-induced lipid peroxidation in rat pancreas. Comp. Clin. Pathol.. 2014;24:1103-1110.

- [Google Scholar]

- Molecular docking and pharmacokinetic prediction of herbal derivatives as a maltase-glucoamylase inhibitor. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res.. 2017;10:392.

- [Google Scholar]

- Preliminary phytochemistry, antioxidant activities, and GC/MS of the most abundant compounds of different solvent fractions of the plant Bridelia ferruginea Benth used locally in the management of diabetes. J. Pharma. Phytochem.. 2021;10(3):154-164.

- [Google Scholar]

- Determination of antioxidant and anticancer activities together with total phenol and flavonoid contents of Cleidion javanicum Bl. and Bridelia retusa (L.) A. Juss. Chiang Mai J. Sci.. 2016;43:534-545.

- [Google Scholar]

- Docking studies on antidiabetic molecular targets of phytochemical compounds of Syzygium cumini (L.) Skeels. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res.. 2016;9(9):287-293.

- [Google Scholar]

- Inhibition of alpha-glucosidase and alpha-amylase by flavonoids. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol.(tokyo). 2006;52(2):149-153.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phytochemical characterization and anti-inflammatory activity of Bridelia retusa bark Spreng. in acute and chronic inflammatory conditions: A possible mechanism of action. EJPMR. 2017;4:686-696.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of solvents on total phenolics, antioxidant and antimicrobial properties of Bridelia retusa Spreng. stem bark. IJNPR. 2011;2:442-447.

- [Google Scholar]

- In silico molecular docking on bioactive compounds from Indian medicinal plants against type 2 diabetic target proteins: A computational approach. Indian J. Pharm. Sci.. 2021;83(6):1273-1279.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antiviral phytocompounds “ellagic acid” and “(+)-sesamin” of Bridelia retusa identified as potential inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro using extensive molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulation studies, binding free energy calculations, and bioactivity prediction. Struct. Chem. 2022:1-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- CHARMM General Force Field: A force field for drug-like molecules compatible with the CHARMM all-atom additive biological force field. J. Comput. Chem.. 2010;31:671-690.

- [Google Scholar]

Appendix A

Supplementary material

Supplementary material to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2024.103411.

Appendix A

Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary material to this article: