Translate this page into:

Synthesis, physicochemical, optical, thermal and TD-DFT of (E)-N′-((9-ethyl-9H-carbazol-3-yl)-methylene)-4-methyl-benzene-sulfonohydrazide (ECMMBSH): Naked eye and colorimetric Cu2+ ion chemosensor

⁎Corresponding authors. suleimanshtaya@najah.edu (M. Suleiman), ismail.warad@qu.edu.qa (I. Warad)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Benzene-sulfonohydrazide (ECMMBSH) Schiff base has been made available in an excellent yield via reflux dehydrate of 4-methylbenzene-sulfonohydrazide with 9-ethyl-9H-carbazole-3-carbaldehyde in EtOH. The synthesis of the ECMMBSH was monitored via two main spectroscopic techniques FT-IR and UV–vis tools; ECMMBSH was characterized via MS, 1H NMR, FT-IR, CHN-EA, TG/DTG, EDX, and UV–vis., analysis. Moreover, DFT-optimized, Molecular Electrostatic Potential (MEP) and MAC/NPA-charge models were performed for ECMMBSH. The HOMO/LUMO and Density of State (DOS) calculated energy levels were compared to Tuac experimental optical energy gap values in methanol. Additionally, the TD-DFT and UV–vis. experimental absorption behavior was matched under the same condition. Moreover, the chemo-sensation effect of the ECMMBSH towered Cu2+ ions via complexation was evaluated by naked eye in addition to the UV–vis spectrophotometric measurements.

Keywords

Copper(II)

NMR

Schiff base

DFT

Sensation

1 Introduction

Schiff bases (S.B.) are an essential N-ligand class of organic material where the C⚌N— main functional group is capable to couple via treating the primary amine with ketones or aldehyde without catalysts or with utilizing pyridine or trimethylamine as basic catalysts or sulphuric, acetic, and hydrochloric acids as acidic catalysts (Shafaatian et al., 2016; Hossain et al., 1996; Abbasi et al., 2018; Pervaiz et al., 2019; Trzesowska-Kruszynska, 2012; Dehghani-Firouzabadi and Motevaseliyan, 2014; Johnson and Dhanaraj, 2020; Khan et al., 2012; Eckenhoff et al., 2012; Ahmadi and Amani, 2012; Rajasekar et al., 2010; Konstantinovic et al., 2003; Routier et al., 1996; Wu et al., 2007). Aromatic Schiff base ligands are more common since it is more stable compared to the aliphatic analogue due to the aromatic conjugated structure that provides the azo-methine from free radical polymerization processes (Trzesowska-Kruszynska, 2012; Dehghani-Firouzabadi and Motevaseliyan, 2014; Johnson and Dhanaraj, 2020; Eckenhoff et al., 2012; Khan et al., 2012). The S.B ligands own many apps in several fields of chemistry, biology, and medicine. For example, several biological apps as antifungal, anti-inflammatory, anticancer, antibacterial, anti-plasmodial, antioxidant, anti-depressant and anti-corrosion have been reported (Sousa et al., 2012; Chatterjee et al., 2014; Badran et al., 2021; Badran et al., 2019; Warad et al., 2017c; Rouifi et al., 2019; Warad et al., 2014; Rbaa et al., 2019).

Moreover, S.B can be considered as one of the broadest and best chelates or polychelates N-ligands in the coordination of metal ions centers. Hydrazones Schiff base (HSB) containing azomethine functional group is a private type of such bases. HSB derivatives offering a better and broad diversity of medical activities like antiepileptic, antiviral, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, analgesic, antioxidant, anticholinesterase, and anticancer (Warad et al., 2017a; Saleemh et al., 2017; Warad et al., 2017b; Masoud et al., 2007; Despaigne et al., 2009; Al-Rimawi et al. 2016; Lindner et al., 2003).

Sulfonohydrazones Schiff bases have been made available mostly due to the chelate effect which made it an excellent ligand complex (Maurya et al., 2015). Their antifungal and antimicrobial biological properties received considerable attention (Hu et al., 2015), especially the ones with transition metal ions complexes containing heterocyclic parts (Jang et al., 2017). Binding of these ligands to the metal centers ions are desired due to the increased antifungal and antibacterial properties compared to the free ligands. Due to the colorimetric binding ability of such ligands to transition ions metal, there is still a need to develop a way of sensation to detect some of the heavy toxic elements like Cu2+ and Ru2+ in our environment via polychelate ligand (Das et al., 2019; Lu et al., 2003; Al-Zaqri et al., 2020a, 2020b; Warad et al., 2020).

Herein a new benzene-sulfonohydrazide Schiff base (ECMMBSH) was prepared then characterized via MS, 1H NMR, CHN-EA, UV–vis., IR, and TG/DTG thermal analysis. Moreover, the ECMMBSH was computed using the DFT/level theory where the computed parameters were compared to the experimental results. Finally, the ECMMBSH naked eye colorimetric chemo-sensation of Cu2+ element was supported via UV–vis spectroscopy.

2 Experimental

2.1 Instrumentation and chemicals

CHN-EA was performed on an Elementar-Vario EL analyzer. TG/DTG was recorded on TGA Perkin-Elmer. FT-IR spectroscopy was carried out using 1000 FT-IR spectrometer Perkin-Elmer Spectrum. UV–Vis was recorded on a TU-1901double-beam UV–visible spectrophotometer. All the chemicals were purchased from Sigma Company.

2.2 Synthesis of ECMMBSH

(0.032 mol) 4-methylbenzenesulfonohydrazide with (0.034 mol) 9-ethyl-9H-carbazole-3-carbaldehyde were added to 30 ml of EtOH, then the mixture was subjected to 4 h stirred and reflux conditions. The mixture was subjected to vacuum until its volume was reduced to 1.5 ml, adding of 40 ml dry of ether resulted in a product precipitation which was washed thoroughly with n-hexane.

Yield: 80% yellow powder with m. p = 185 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 1.3 (t, 3H, CH3 of ethyl), 2.3 (s, 3H, CH3-Ph), 4.5 (q, 3H, CH3-CH2), 7–8 (m, 10H, Ph), 8.3 (s, 1H, >C⚌N—), 11.5 (s, 1H, —NH—N⚌C).

2.3 Computation

All the DFT calculation were performed via Gaussian 09 software under DFT 6-311G(d,p) level theory.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Preparation, CHN-EA and MS

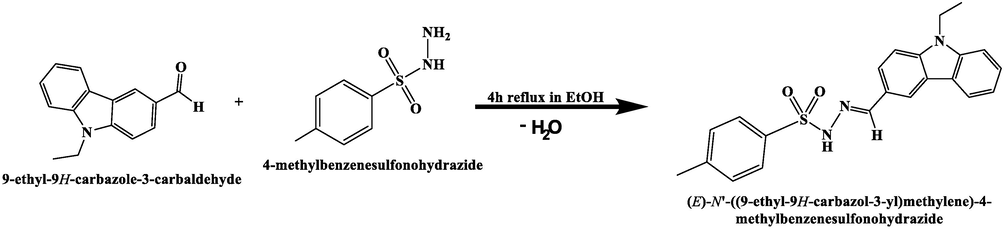

In ethanol solvent, the condensation of 1:1 M ratio of 4-methylbenzenesulfonohydrazide with the aldehyde in an open atmosphere reflux condition formed the desired benzene-sulfonohydrazide (ECMMBSH) in high yield (Scheme 1). The new ECMMBSH has a yellow color and solid in its nature, highly soluble in CH2Cl2, DMF, and DMSO, lower solubility in MeOH and water, and insoluble n-hexane.

Synthesis of ECMMBSH ligand.

The desired ECMMBSH was identified using CHN-EA, MS, FT-IR, NMR, TG/DTG and UV–Vis. Moreover, the DFT stimulation like optimization, MEP, LUMO/HOMO, DOS and TD-DFT under DFT 6-311G(d,p) level.

CHN-elemental analysis and MS of the ECMMBSH agreement well with it proposed molecular formula. For C22H21N3O2S, Calcd. C, 67.50; and H, 5.41%; found C, 67.30; and H, 5.3%. The TOF-MS of the ECMMBSH was in consistent with formula: m/z = 391.1 [M+] (theo. m/z = 391.5). The atomic content and purity have been verified by EDX, the spectrum of EDX reflected the existence of O, N, C, and S only corresponding to the empirical formulate of ECMMBSH ligand.

3.2 Optimized, MEP and MAC/NPA

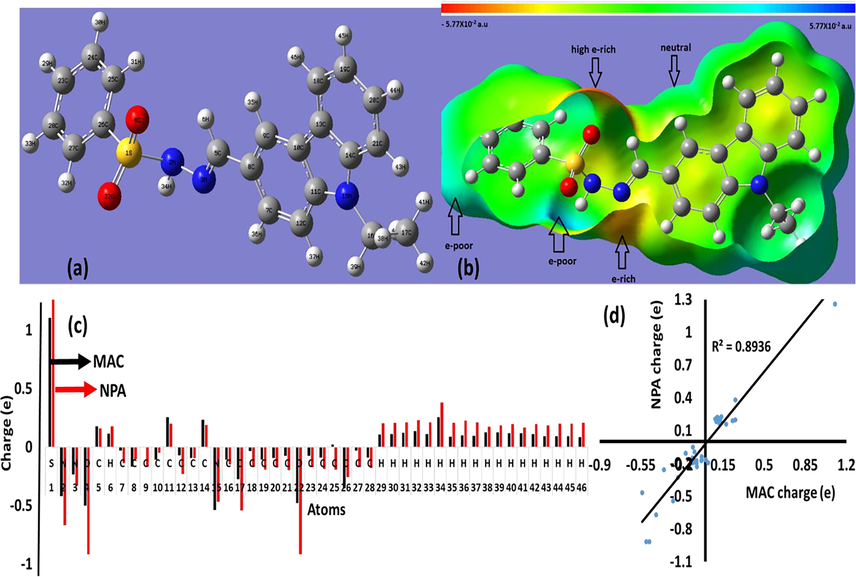

The ECMMBSH ligand structure was subjected to DFT-B3LYP optimization as seen in Fig. 1a. The DFT gaseous state optimization revealed the ECMMBSH with E-isomer and not Z-one and this is not surprising since in gaseous state the e-isomers exhibits a lower internal repulsion energy compared to Z-isomer. Moreover, the calculated angles and bond length values for the ECMMBSH E-isomer are illustrated in Table 1. The MEP map calculation shows the surface of ECMMBSH with three colors: the high e-rich positions characterized by a red color that covered the O atoms of SO2 groups and N of imine Schiff base functional group, the H of aromatic and ethyl function group has a blue color due to its e-poor aspects, deep blue color distinguished the H in HN reflecting it as e-poorer proton, the third functional groups were found to be neutral since they are green in color as seen in Fig. 1b. To evaluate the charge of each atom in ECMMBSH NPA and MAC calculation charge models were performed as seen in Fig. 1b and Table 2. Generally, NPA and MAC supported MEP calculation resulting in all the O and N atoms of Schiff base with negative in charge, meanwhile, the S and all protons atoms with positive charge, as expected, the proton of amine was detected with the highest positive charge as seen Fig. 1c and Table 2. Both NPA and MAC charge models coincided in measuring the charge of each atom of ECMMBSH since the degree of compatibility reached almost 90%, as seen in Fig. 1d

(a) Optimized, (b) MEP, (c) MAC/NPA charge, and (d) MAC vs. NPA charge.

No.

Bond

Å

No.

Angle

(o)

1

S1

N2

1.7471

1

N2

S1

O4

106.34

2

S1

O4

1.4589

2

N2

S1

O22

111.64

3

S1

O22

1.4617

3

N2

S1

C26

98.54

4

S1

C26

1.7981

4

O4

S1

O22

120.31

5

N2

N3

1.4159

5

O4

S1

C26

109.9

6

N3

C5

1.2834

6

O22

S1

C26

107.94

7

C5

C8

1.4607

7

S1

N2

N3

118.61

8

C7

C8

1.4144

8

N2

N3

C5

116.45

9

C7

C12

1.3829

9

N3

C5

C8

121.24

10

C8

C9

1.3985

10

C8

C7

C12

121.62

11

C9

C10

1.3931

11

C5

C8

C7

121.65

12

C10

C11

1.4192

12

C5

C8

C9

118.7

13

C10

C13

1.4471

13

C7

C8

C9

119.65

14

C11

C12

1.401

14

C8

C9

C10

119.8

15

C11

N15

1.3839

15

C9

C10

C11

119.48

16

C13

C14

1.4183

16

C9

C10

C13

133.93

17

C13

C18

1.3969

17

C11

C10

C13

106.59

18

C14

N15

1.3925

18

C10

C11

C12

121.24

19

C14

C21

1.396

19

C10

C11

N15

109.2

20

N15

C16

1.4558

20

C12

C11

N15

129.56

21

C16

C17

1.5317

21

C7

C12

C11

118.2

22

C18

C19

1.3897

22

C10

C13

C14

106.51

23

C19

C20

1.4028

23

C10

C13

C18

133.95

24

C20

C21

1.3911

24

C14

C13

C18

119.54

25

C23

C24

1.3958

25

C13

C14

N15

109.04

26

C23

C28

1.3929

26

C13

C14

C21

121.48

27

C24

C25

1.3903

27

N15

C14

C21

129.49

28

C25

C26

1.394

28

C11

N15

C14

108.65

29

C26

C27

1.392

29

C11

N15

C16

125.71

30

C27

C28

1.3938

30

C14

N15

C16

125.58

No.

Atom

MAC

NPA

No.

Atom

MAC

NPA

1

S

1.102349

1.25898

24

C

−0.09003

−0.18476

2

N

−0.41945

−0.66874

25

C

0.022174

−0.19506

3

N

−0.23341

−0.32983

26

C

−0.35388

−0.25651

4

O

−0.50273

−0.91461

27

C

−0.03119

−0.16986

5

C

0.176066

0.1594

28

C

−0.08816

−0.18026

6

H

0.114058

0.17843

29

H

0.108079

0.20442

7

C

−0.03211

−0.13894

30

H

0.108734

0.20669

8

C

−0.167

−0.10554

31

H

0.121761

0.21069

9

C

0.001131

−0.16625

32

H

0.136436

0.22777

10

C

−0.10824

−0.04908

33

H

0.109181

0.20926

11

C

0.253734

0.19796

34

H

0.253581

0.38121

12

C

−0.0715

−0.23038

35

H

0.086581

0.20861

13

C

−0.09429

−0.09352

36

H

0.099677

0.22447

14

C

0.231138

0.1893

37

H

0.096323

0.2097

15

N

−0.53929

−0.46854

38

H

0.126264

0.17164

16

C

−0.10897

−0.14935

39

H

0.126877

0.18623

17

C

−0.27571

−0.54127

40

H

0.118902

0.19529

18

C

−0.03525

−0.17226

41

H

0.118822

0.16533

19

C

−0.10802

−0.19485

42

H

0.110407

0.19752

20

C

−0.09466

−0.17437

43

H

0.093428

0.18332

21

C

−0.07636

−0.19811

44

H

0.091595

0.20057

22

O

−0.47771

−0.91662

45

H

0.091185

0.1991

23

C

−0.0748

−0.17287

46

H

0.084282

0.20566

3.3 1H NMR of ECMMBSH

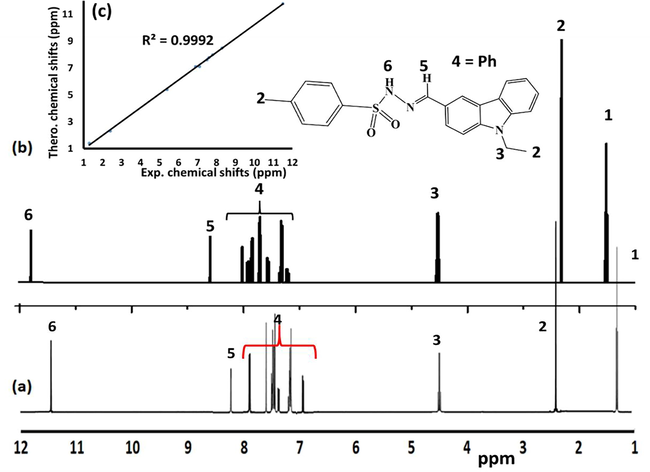

The exp. and theo. 1H NMR spectra of the ECMMBSH were performed in CDCl3 as in Fig. 2, Fig. 2a reflects the 1H NMR spectra, the triplet signal for CH3 of ethyl group was detected at δ ∼ 1.3 ppm, the single at δ ∼ 2.3 ppm attributed to Me of CH3-Ph part in ECMMBSH, the quartet signal for CH2 of ethyl group was detected at δ ∼ 4.5 ppm, the Ph’s protons were recorded in between 7 and 8 ppm, the (N⚌CH) azomethine proton signal was recorded at δ ∼ 8.3 ppm, signal for the proton of N—H was recorded at δ ∼ 11.5 ppm. The theoretical and experimental 1H NMR of ECMMBSH ligand (Fig. 2b) reflected an excellent degree of matching with 0.9992 graphical correlation as seen in Fig. 2c. Moreover, only a slight shift in the chemical shifts for each proton were recorded by comparing individually the experimental to theoretical 1H NMR. Unfortunately, due to lack in the solubility of ECMMBSH in deuterated solvents 13C NMR was very weak to be reported.

1H NMR spectra of ECMMBSH in CDCl3 (a) Experimental, (b) Theoretical, and (c) Experimental vs. theoretical chemical shifts relation.

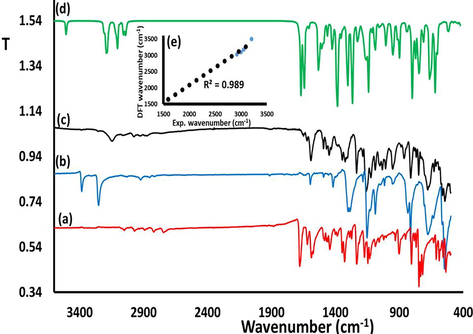

3.4 Ir

FT-IR was used to monitor the formation reactions of the desired ECMMBSH before and after mixing the starting materials. The individually FT-IR spectra of both 4-methyl-benzenesulfonohydrazide and the aldehyde were compared to the product ECMMBSH (after allowing it to condense) as see in Fig. 3a. The ECMMBSH formation was supported via two major findings: (1). The stretching vibration N-H2 in 4-methyl-benzenesulfonohydrazide at 3383 cm−1 was totally absent and the NH at 3254 cm−1 displayed a down shift to 3152 cm−1 as in Fig. 3a and (2) the C⚌O stretching of the aldehyde at 1679 cm−1 was shifted to 1590 cm−1 supporting the formation C⚌N- functional group as seen Fig. 3c.

Exp. FT-IR spectra recorded for (a) the aldehyde b) 4-methyl-benzene-sulfonohydrazide, c) ECMMBSH (d) DFT-IR of ECMMBSH, and (e) DFT/Exp.-IR relation.

The theoretical DFT-IR of ECMMBSH was performed to evaluate the degree of similarity to the experimental IR as shown in Fig. 3d. The exp. IR and the DFT theoretical wavenumbers resulted a linear relationship with 0.989 correlation coefficient reflecting excellent agreement as in Fig. 3e.

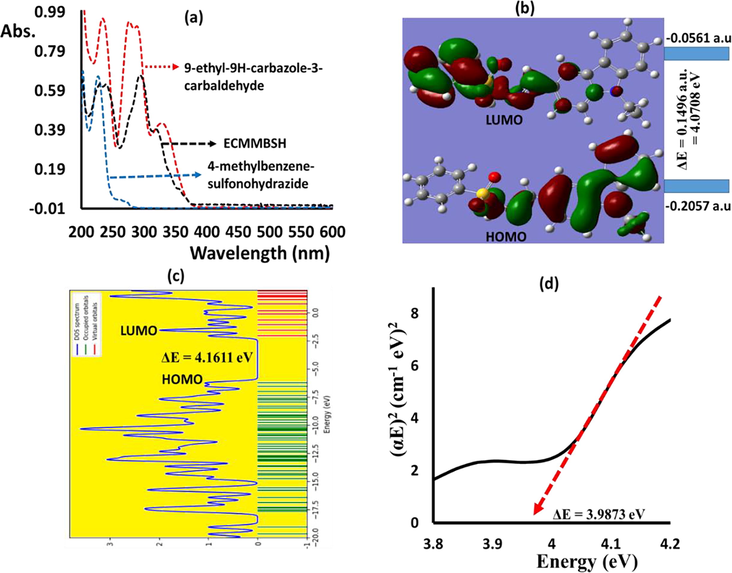

3.5 UV–Vis, HOMO/LUMO, DOS, and Tauc’s optical gap

The UV–Visible of the ECMMBSH and its starting material were recorded in methanol as seen Fig. 4a. The UV–Vis measurements of the ECMMBSH showed a compensation of both the UV–Vis the aldehyde and 4-methyl-benzene-sulfonohydrazide reactants. The UV–Vis of the ECMMBSH showed highly intense transitions bands with two heads at λmax = 233 and 241 nm with ε = 3.0 × 104 M−1 L−1, intense band with λmax = 297 nm with ε = 5.0 × 104 M−1 L−1, and weak band at 323 nm with ε = 1.0 × 104 M−1 L−1, these bands corresponded mostly to the π-π*, π-n and n-π* e-transfer respectively. The LUMO/HOMO shape and energy levels were schematic performance in methanol solvent as seen in Fig. 4b. In the HOMO electrons distribution over the orbitals focused on aldehyde part of ECMMBSH with −5.597385 eV, meanwhile, the LUMO focused on the 4-methylbenzenesulfonohydrazide with part of ECMMBSH with −1.527 eV, the energy gap found to be ΔEHOMO/LUMO = 4.071 eV as illustrated in Fig. 4b. The DOS energy gap calculated was ΔEDOS = 4.161 eV as seen in Fig. 4c; the two ΔE of both LUMO/HOMO and DOS values showed a rather high convergence as seen in Fig. 4c. The experiment optical energy gap value of ECMMBSH in methanol solvent using the Tauc’s equation was evaluated as in Fig. 4d. The optical energy gap found to be = 3.987 eV, such seen is highly proportionate with the ΔEHOMO/LUMO and ΔEDOS DFT calculated values.

(a) RT Experimental UV–Vis. spectra, (b) HOMO/LUMO energy diagrams, (c) DOS, and (d) Exp. Tauc’s energy gap of the ECMMBSH in methanol.

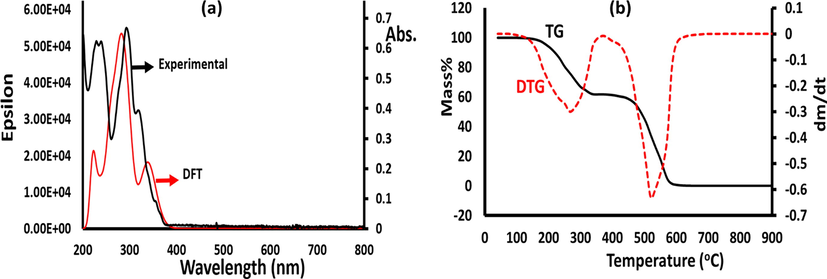

3.6 TD-DFT/UV–Vis. and TG/DTG

The UV–Visible behaviors of the ECMMBSH in MeOH in both experimental and theoretical TD-DFT in the 200–800 nm range are shown seen Fig. 5a. In general, the three experimental main peaks at λmax = 233, 297, 323 nm that sited to π-π*, π-n and n-π*, e-transitions respectively in Fig. 5a was supported theoretically via TD-DFT computation. The TD-DFT of the ECMMBSH showed again a three-band in the UV area with λmax = 224 nm attributed mainly to HOMO->LUMO (92%), meanwhile the visible band λmax = 278 nm attributed mainly to H-1->L + 1 (85%), and λmax = 335 nm attributed to H-4->L + 2 (69%) (Fig. 5b). The detail of TD-DFT information like wavelength (nm), calculated energy (cm−1) and transition oscillator strength (f) of the first 16 bands (with f > 0.01) are illustrated in Table 3. Moreover, several solvents, such as CH2Cl2, DMSO and DMF, have been tried; however, they do not alter the electronic behaviors of ECMMBSH, either in theory or in experimental fields. In conclusion, theoretical TD-DFT and the experimental UV–visible behavior of ECMMBSH are in an acceptable correlation.

(a) TD-DFT/UV–vis. spectra, and (b) TG/DTG of ECMMBSH.

No.

E (cm−1)

λ (nm)

Osc. Str. (f)

Major contribution

1

29083.5

343.8

0.1608

HOMO->LUMO (92%)

2

30298.2

330.0

0.1179

H-2->LUMO (39%), H-1->LUMO (49%)

3

32471.0

307.9

0.0044

H-2->LUMO (23%), H-1->LUMO (14%), HOMO->L + 1 (54%)

4

33998.6

294.1

0.4111

H-2->LUMO (24%), H-1->LUMO (33%), HOMO->L + 1 (31%)

5

35917.4

278.4

0.5194

H-1->L + 1 (85%)

6

38240.3

261.5

0.3456

H-3->LUMO (84%)

7

39133.2

255.53

0.0488

H-2->L + 1 (45%), HOMO->L + 4 (38%)

8

40076.0

249.5

0.0186

H-4->LUMO (86%)

9

40093.0

249.4

0.0833

H-3->L + 1 (10%), H-2->L + 1 (42%), HOMO->L + 4 (30%)

10

41622.2

240.2

0.0608

H-3->L + 1 (46%), H-1->L + 4 (30%), HOMO->L + 4 (15%)

11

41990.8

238.1

0.0102

H-5->L + 2 (50%), H-4->L + 3 (31%)

12

42484.4

235.3

0.0728

H-6->LUMO (55%), H-1->L + 4 (25%)

13

44204.0

226.2

0.0005

H-2->L + 3 (82%), H-1->L + 3 (10%)

14

44332.2

225.5

0.0305

H-8->LUMO (12%), H-7->LUMO (24%), H-3->L + 2 (50%)

15

45066.2

221.9

0.0879

H-3->L + 1(14%), H-1->L + 4(18%), H-1->L + 5(10%), HOMO->L + 5(31%)

16

45370.3

220.4

0.1498

H-4->L + 2 (69%)

The TG/DTG attitude of ECMMBSH ligand was achieved in 22–900 °C temperature scale with 10 °Cmin−1 heating rate at open room temperature condition (Fig. 5b). The ECMMBSH ligand was found to be stable up to ∼160 °C without any loss in its mass, at temperature higher than 160 °C the molecule started to decompose via two broad steps, the first step was outset from 160 °C and finished at 320 °C with TDTA = 282 °C and ∼38% mass lost. The 2nd step was outset from 480 °C and end at 610 °C with TDTA = 520 °C and ∼62% mass lost. Moreover, the pure organic ECMMBSH ligand was usually decomposed completely to light gasses (CO, CO2, NOx and SOx) since at the end of the decomposition process zero mass residue was observed as seen in Fig. 5b.

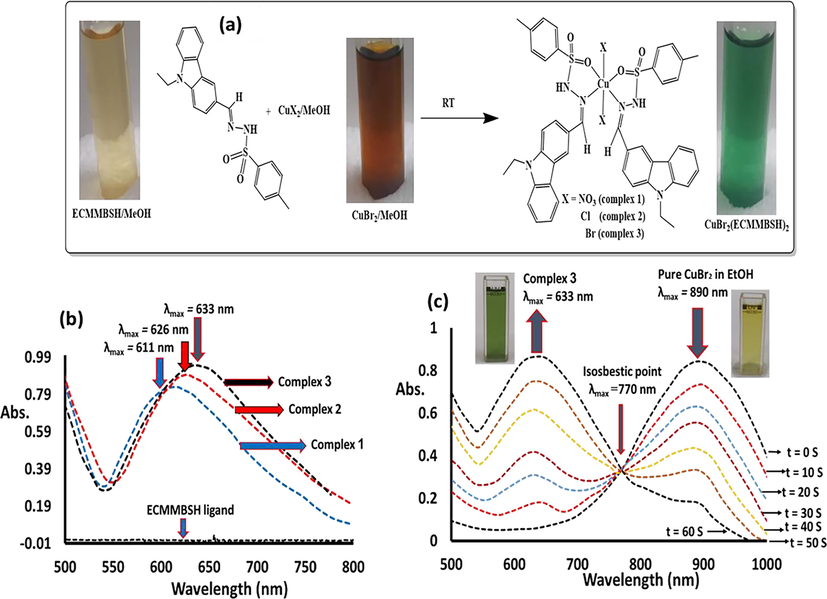

3.7 A naked eye and spectroscopy colorimetric Cu2+ sensor

The colorimetric naked eye behavior of the ECMMBSH (light yellow) complexation with CuX2/MeOH (for example CuBr2/MeOH, brown) before and after direct mixed to produced CuX2(ECMMBSH)2 (X = NO3 complex 1, Cl complex 2 and Br complex 3(has been illustrated in Fig. 6. The absorption of ECMMBSH in the presence of CuX2/MeOH was displayed in Fig. 6a. Due to the complexation between the ECMMBSH and Cu(II) solution the color was changed to green without depending on the X ligand, a slight shift in maximum was observed, Cu(NO3)2/ECMMBSH revealed with λmax = 611 nm, CuCl2/ECMMBSH revealed with λmax = 626 nm and CuBr2/ECMMBSH revealed with λmax = 633 nm in Fig. 6a. The shifts in λmax values are consistent with d-splitting field theory and spectrophotometric series strength since NO3 > Cl > Br ligands strength are recorded as Fig. 6a. The ECMMBSH displayed a remarkable sensitivity to Cu(II) solution even at very low copper concentration. The visible complexation process of CuBr2/MeOH with ECMMBSH/MeOH was monitored in between 500 and 1000 nm. The peak at 890 nm that characteristic of 1 × 10-3 M pure brown CuBr2/MeOH solution absorbance gradually and rapidly decreased by the addition of excess ECMMBSH/MeOH (1x10-2 M) parallel to the appearance of the green CuBr2(ECMMBSH)2 complex at λmax = 633 nm with one isosbestic point at λmax 770 nm. The colorimetric complexation of ECMMBSH with CuBr2/MeOH at RT was found to be very fast, as one minute was sufficient to complete this process considering that a measurement every ∼10 s was recorded as displayed in Fig. 6b.

(a) Necked eye colorimetric complexation of ECMMBSH with CuX2/MeOH, (b) Absorption behavior of ECMMBSH with CuX2/MeOH (X = NO3 complex 1, Cl complex 2 and Br complex 3(, and (c) Time-dependence of complexation of CuBr2/MeOH with ECMMBSH ligand.

4 Conclusion

Benzene-sulfonohydrazide (ECMMBSH) ligand was made available in a very high yield. The condensation reaction was successfully monitored via UV–Vis and IR spectroscopy. Moreover, the product was characterized via CHN-EA, MS, 1H NMR, EDX, CHN-EA, UV–Vis., IR, and TGA thermal analysis. The ECMMBSH ligand showed a high stability, in addition, it decomposed in two steps. The DFT-optimized, MEP and MAC/NPA were performed for ECMMBSH, the HOMO/LUMO and DOS calculated energy levels supported the Tuac experimental optical energy gap result. The TD-DFT and UV–vis. experimental absorption behaviors in MeOH solvent were in high agreement degree, moreover, the ECMMBSH colorimetric sensation effect towards Cu2+ ions was figure out via the naked eye and UV-spectrophotometric method. The time-dependent chemo-sensation complexation of CuBr2/MeOH with ECMMBSH ligand was successfully monitored by UV–vis. Spectroscopy.

Acknowledgement

The authors extend their appreciation to the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSP-2021/381), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- In vitro cytotoxic activity of a novel Schiff base ligand derived from 2-hydroxy-1-naphthaldehyde and its mononuclear metal complexes. J. Mol. Struct.. 2018;1173:213-220.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, spectroscopy, thermal analysis, magnetic properties and biological activity studies of Cu (II) and Co (II) complexes with Schiff base dye ligands. Molecules. 2012;17(6):6434-6448.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anticancer activity, antioxidant activity, and phenolic and flavonoids content of wild Tragopogon porrifolius plant extracts. Evidence-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2016:2016.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and amide imidic prototropic tautomerization in thiophene-2-carbohydrazide: XRD, DFT/HSA-computation, DNA-docking, TG and isoconversional kinetics via FWO and KAS models. RSC Adv.. 2020;10(4):2037-2048.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, physicochemical, thermal, and XRD/HSA interactions of mixed [Cu(Bipy)(Dipn)](X)2 complexes: DNA binding and molecular docking evaluation. J. Coord. Chem.. 2020;73(23):3236-3248.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of alkyl derivation on the chemical and antibacterial properties of newly synthesized Cu(II)-diamine complexes. Moroccan J. Chem.. 2019;7:1-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Experimental and first-principles study of a new hydrazine derivative for DSSC applications. J. Mol. Struct.. 2021;1229:129799.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mechanism of antibacterial activity of copper nanoparticles. Nanotechnology. 2014;25(13):135101.

- [Google Scholar]

- Schiff Base Derived from 4, 4′-methylenedianiline and p-anisaldehyde: colorimetric Sensor for Cu2+, Paper Strip Sensor for Al3+ and Fluorescent Sensor for Pb 2+. J. Fluoresc.. 2019;29(6):1467-1474.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and characterization of four new unsymmetrical potentially pentadentate Schiff base ligands and related Zn(II) and Cd(II) complexes. Eur. J. Chem.. 2014;5(4):635-638.

- [Google Scholar]

- Copper (II) and zinc (II) complexes with 2-formylpyridine-derived hydrazones. Polyhedron. 2009;28(17):3797-3803.

- [Google Scholar]

- Structural characterization and investigation of iron (III) complexes with nitrogen and phosphorus based ligands in atom transfer radical addition (ATRA) Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2012;382:84-95.

- [Google Scholar]

- The preparation, characterization, crystal structure and biological activities of some copper(II) complexes of the 2-benzoylpyridine Schiff bases of S-methyl-and S-benzyldithiocarbazate. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 1996;249(2):207-213.

- [Google Scholar]

- Highly sensitive and selective colorimetric naked-eye detection of Cu2+ in aqueous medium using a hydrazone chemosensor. Sens. Actuators B Chem.. 2015;215:241-248.

- [Google Scholar]

- A single colorimetric sensor for multiple targets: the sequential detection of Co 2+ and cyanide and the selective detection of Cu2+ in aqueous solution. RSC Adv.. 2017;7(29):17650-17659.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biological and molecular modeling studies on some transition metal (II) complexes of a quinoxaline based ONO donor bishydrazone ligand. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020:1-13.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis of acylhydrazide Schiff bases and their anti-oxidant activity. Med. Chem. 2012;8:705-710.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and characterization of Co (II), Ni (II), Cu (II) and Zn (II) complexes with 3-salicylidenehydrazono-2-indolinone. J. Serbian Chem. Soc.. 2003;68(8-9):641-647.

- [Google Scholar]

- Supported organometallic complexes Part 34: synthesis and structures of an array of diamine (ether–phosphine) ruthenium (II) complexes and their application in the catalytic hydrogenation of trans-4-phenyl-3-butene-2-one. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2003;350:49-56.

- [Google Scholar]

- Supported Organometallic Complexes. XXXVIII [1] Bis (methoxyethyldimethylphosphine) ruthenium (II) Complexes as Transfer Hydrogenation Catalysts. Zeitschrift für Anorg. und Allg. Chemie. 2003;629:1308-1315.

- [Google Scholar]

- Spectral properties of some metal complexes derived from uracil–thiouracil and citrazinic acid compounds. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc.. 2007;67(3-4):662-668.

- [Google Scholar]

- Oxidative bromination of monoterpene (thymol) using dioxidomolybdenum (VI) complexes of hydrazones of 8-formyl-7-hydroxy-4-methylcoumarin. Polyhedron. 2015;96:79-87.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, spectral and antimicrobial studies of amino acid derivative Schiff base metal (Co, Mn, Cu, and Cd) complexes. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc.. 2019;206:642-649.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, characterization, and antimicrobial activities of nickel (II) and copper (II) Schiff-base complexes. J. Coord. Chem.. 2010;63(1):136-146.

- [Google Scholar]

- Novel Cu (II) and Zn (II) complexes of 8-hydroxyquinoline derivatives as effective corrosion inhibitors for mild steel in 1.0 M HCl solution: computer modeling supported experimental studies. J. Mol. Liq.. 2019;290:111243

- [Google Scholar]

- Performance and computational studies of new soluble triazole as corrosion inhibitor for carbon steel in HCl. Chem. Data Collect.. 2019;22:100242.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis of a functionalized Salen− Copper complex and its interaction with DNA. J. Org. Chem.. 1996;61(7):2326-2331.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diethylenetriamine/diamines/copper (II) complexes [Cu (dien)(NN)] Br 2: synthesis, solvatochromism, thermal, electrochemistry, single crystal, Hirshfeld surface analysis and antibacterial activity. Arab. J. Chem.. 2017;10(6):845-854.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, characterization, spectroscopic and theoretical studies of new zinc (II), copper (II) and nickel (II) complexes based on imine ligand containing 2-aminothiophenol moiety. J. Mol. Struct.. 2016;1123:191-198.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, characterization and antibacterial studies of a copper (II) levofloxacin ternary complex. J. Inorg. Biochem.. 2012;110:64-71.

- [Google Scholar]

- Copper complex of glycine Schiff base: In situ ligand synthesis, structure, spectral, and thermal properties. J. Mol. Struct.. 2012;1017:72-78.

- [Google Scholar]

- Crystal structure, Hirshfeld surface, physicochemical, thermal and DFT studies of (N1E, N2E)-N1, N2-bis ((5-bromothiophen-2-yl) methylene) ethane-1, 2-diamine N2S2 ligand and its [CuBr(N2S2)]Br complex. J. Mol. Struct.. 2017;1142:217-225.

- [Google Scholar]

- New isomeric Cu(NO2-phen)2Br]Br complexes: Crystal structure, Hirschfeld surface, physicochemical, solvatochromism, thermal, computational and DNA-binding analysis. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol.. 2017;171:9-19.

- [Google Scholar]

- Design and structural studies of diimine/CdX2 (X= Cl, I) complexes based on 2, 2-dimethyl-1, 3-diaminopropane ligand. J. Mol. Struct.. 2014;1062:167-173.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, solvatochromism and crystal structure of trans-[Cu(Et2NCH2CH2NH2)2.H2O](NO3)2 complex: experimental with DFT combination. J. Mol. Struct.. 2017;1148:328-338.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and physicochemical, DFT, thermal and DNA-binding analysis of a new pentadentate N 3 S 2 Schiff base ligand and its [CuN3S2]2+ complexes. RSC Adv.. 2020;10(37):21806-21821.

- [Google Scholar]

- Copper(II) complexes of salicylaldehyde hydrazones: synthesis, structure, and DNA interaction. Chem. Biodivers.. 2007;4(9):2198-2209.

- [Google Scholar]