Translate this page into:

Prognostic value of ANDC score and CRP-derived inflammatory markers in hospitalized adult patients with COVID-19

⁎Corresponding author. sysalem@zu.edu.eg (Salem Youssef Mohamed),

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background:

SARS-CoV-2 has been a causative agent of severe acute respiratory syndrome since last 2019. Early diagnosis of severe cases is crucial to decrease a patient's hospital stay and death risk. severity and prognosis

Patients and Methods:

This retrospective study included COVID-19 patient underwent chest computed tomography scan and a battery of laboratory tests, including measurements of leukocytes, neutrophils, lymphocytes, lactic dehydrogenase, creatinine level, ferritin, D-dimer, albumin, and C-reactive protein. In addition, the CRP to lymphocyte ratio (CLR), CRP to albumin ratio (CAR), CRP to platelet ratio (CPR) and the ANDC score. Patients' clinical outcomes including length of hospital stays (LOS) and mortality were recorded.

Results:

Out of 98 patients, 51 patients had passed away. There was a statistically significant difference between survivors and non-survivors regarding age, TLC, ANC, NLR, D-Dimer, and albumin. Moreover, a highly statistically significant difference regarding CRP levels, CAR, CPR, CLR, and ANDC was noted. Serum CRP level > 123 ng/ml, CAR > 36.77, CPR level > 462, and CLR > 84 had sensitivity; (64.71 %, 66.6 %, 72.5 %, and 76.4 %, respectively) and specificity; (85.1 %, 78.7 %, 72.3 %, and 72.3 % respectively) in mortality prediction. Meanwhile, the ANDC score was the most sensitive indicator (88.2 %) for mortality outcome. Multivariable regression analysis revealed that aging, CPR, and ANDC level were independently associated with mortality with H.R. [1.025 (1.002–1.050); 2.338 (1.189–4.599) and 2.896 (1.191–7.044)]

Conclusion:

The value of the ANDC score and CRP-derived inflammatory indicators correlate with the likelihood of mortality, so the efficacy of these metrics might assist in urgent early dialogues about treatment escalation.

Keywords

ANDC score

CRP-derived inflammatory markers

COVID-19

Mortality

- COVID-19

-

coronavirus disease-2019

- SARS-CoV-2

-

severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

- CRP

-

C-reactive protein

- CAR

-

CRP to Albumin ratio

- CPR

-

CRP to platelet ratio

- CLR

-

CRP to lymphocyte ratio

- ANDC

-

=_1.14 × age − 20__years_+ 1.63 ×NLR + 5.00 × D −dimer_mg/L_+ 0.14 × CRP mg/L.

- NLR

-

neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio

- TLC

-

total leukocyte count

- LDH

-

lactic dehydrogenase

- NIV

-

non invasive ventilation

- IMV

-

mechanical ventilation

- ICU

-

intensive care unit

Abbreviations

1 Introduction

There was a reported outbreak in Wuhan, China, in December 2019, which promptly became a pandemic with unclear circumstances. At the beginning of the year 2020, scientists successfully isolated a novel virus that belongs to the Beta-corona virus genus of the Coronaviridae family. It was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) in February 2020 (Abbas et al., 2021; Li et al., 2020; Lotfy et al., 2021; Phelan et al., 2020).

In case of COVID-19 pneumonia,a high fever, dry cough, and difficult breathing are the predominant symptoms. The great majority of patients had a mild to moderate illness and were able to recover entirely with conservative therapy. However, 15–30 % of patients may develop severe pneumonia, leading to ARDS, multiple organ failure, or even death (AlOtaibi et al., 2021; Huang et al., 2020; Zayed et al., 2022).

Severely ill patients are challenging to treat due to lack of targeted therapies; so that it is obligatory for a healthcare worker to look for the clinical characteristics of severity and subsequent predictors of mortality to implement the appropriate and early intervention in the hopes of reducing death rates. Recently, it has been shown that age, the presence of cardiovascular co-morbid profile, and diabetes mellitus are factors that may be used to predict mortality. In addition, serum ferritin, D-dimer, and cardiac enzymes have all been found by other researchers as potential biomarkers for predicting severe and fatal illnesses (Weng et al., 2020).

Recent work has resulted in the developing of an integrated ANDC score, which serves for the early classification of COVID-19 patients and treatment guidance (Management protocol of COVID 19 patients by Ministry of Health and population, Egypt Version 1.5., 2021). Consequently, The aim of the current work is to investigate whether the ANDC sore and CRP-derived inflammatory markers might be used to predict COVID-19-infected adult patients with high probability of mortality.

2 Patient and methods

This retrospective study was conducted at Zagazig University Hospitals Isolation unit and Clinical Pathology Department, Egypt from March 2021 to August 2021. That inquiry is congruent with guidelines established by the World Medical Association in its Helsinki Declaration. This research included 98 adult patients who were confirmed by laboratory and radiologically as COVID-19. Patients were above the age of 18. They were diagnosed according to the Egyptian Ministry of Health's Scientific Committee (Goudouris, 2021). Throat swabs were taken from individuals suspected of having SARS-CoV-2 infection to confirm the. In addition, each patient underwent a chest computed tomography (C.T.) scan and a battery of laboratory tests, including measurements of leukocytes, neutrophils, lymphocytes, C-reactive protein, fibrin degradations (D-dimer), creatinine level, albumin, lactic dehydrogenase (LDH) and ferritin. In addition, the CRP to lymphocyte ratio, the CRP to platelet ratio and the CRP to albumin ratio (CLR,CPR,CAR, respectively). The ANDC score was calculated using the following formula:

2.1 Patients' Clinical Outcomes:

The length of hospital stays was measured from admission until the patient either showed signs of recovery and was released from the hospital or passed away.

3 Methods

3.1 Sample collection

Oropharyngeal and nasal swabs were combined and mixed in a tube containing a medium for virus particle transmission. The samples were kept at-80 degrees Celsius in eppendorf tubes until the RNA extraction and RT-qPCR procedures were completed.

3.2 Detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA by RT-qPCR

The QIAamp® Viral RNA small kit was used to extract RNA, and the process was carried out by the guidelines provided by the manufacturer (cat. no. 52906, Qiagen). The extracted RNA's quantity and quality were evaluated using a spectrophotometer with a model number of Nanodrop S1000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

The Agilent Stratagene Mx3000P qPCR System performed a one-step reverse transcription-quantitative PCR analysis. A real-time PCR kit (Primerdesign Ltd, Ref: Z-Path-COMD-19-CE, United Kingdom) was necessary for the one-step RT-qPCR.

The principal focus of this investigation was (RdRP) gene; the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, which could be included inside SARS-CoV-2, will be. The amount of the reaction mix used was twenty microliters. It had the following components: ten microliters of 2X RT-qPCR Master Mix, eight microliters of sample extract, and two microliters of COVID-19 Primer & Probe. The one-step process included performing the reverse transcription by heating the reaction mixture for ten minutes at 55 degrees Celsius. After that, the complementary DNA, or cDNA, was subjected to initial denaturation at a temperature of 95 degrees Celsius for two minutes. Next,denaturation at 95 degrees Celsius for ten seconds, annealing, and extension at 60 degrees Celsius for one minute for 45 cycles, each consisting of. The cycle threshold (Ct) values were noted down, and the samples' results were deemed negative if their Ct values were lower than 40.

3.3 Laboratory evaluation

A sample of 4 cm of peripheral blood was extracted as follows: calculation of NLR and PLR was made by dividing the absolute neutrophils or platelets number by the total number of lymphocytes, respectively, using two milliliters of peripheral venous blood collected in tubes containing EDTA (1.2 mg/ml) for complete blood count (by Sysmex XN1000). Another 2 mL of peripheral venous blood was taken to assay LDH, Ferritin, serum urea, creatinine, and liver enzymes (Cobas 8000, Roch Diagnostic) and to examine the D dimer, CRP (Cobas 6000, Roch Diagnostic). Use a urine sample to determine the albumin/creatine ratio (Cobas 6000Roch Diagnostic).

3.4 Statistical analysis

Normality of the data was initially assessed by the Shapiro Walk test. The Fisher exact and Chi-square tests (2) were used to compare qualitative variables and their statistical significant. To represent the quantitative data, we employed the median and the range. For quantitative variables between two groups,to measure the degree of statistical significance even though the data did not have a normal distribution, the selected test was Mann-Whitney U test. a receiver operating characteristic curve, also known as a ROC curve, which was used in the process of creating threshold values for markers. The Kaplan–Meier method and the log-rank test were used to calculate and analyze hospital survival rates. The Cox regression analysis models included both univariate and multivariate variables. Every one of the statistical comparisons was carried out with two tails, and the existence of a significant difference could be inferred from a P-value that was lower than 0.05. NCSS 12(used for generation of figures), LLC, US and SPSS version 20 (used to run all the statistical analysis); all were used to carry out the task of analyzing the data.

4 Results

A total of 98 confirmed COVID-19 patients were enrolled in the current study. Unfortunately, 51 patients had passed away by the time it was through, and 47 were still alive. Therefore, there was no statistically significant difference between both groups regarding sex or length of hospital stay. At the same time, there was a statistically significant difference between the two groups regarding age, TLC, ANC, NLR, D-Dimer, and albumin (p = 0.013, 0.028, 0.006, <0.001, and 0.029), Table 1. Qualitative variables were expressed as numbers and percentages and compared using the Chi-square X2 test. While Continuous variables are described as mean ± SD for normally disturbed variables and compared using the Independent TT-test and median (range) for nonnormally disturbed variables and compared using the Mann-Whitney U test, TLC: total leukocytic count; ANC: absolute neutrophil count; ALC: absolute lymphocyte count; NLR: neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio; Hb: hemoglobin; CRP: C-reactive protein; CLR: CRP to lymphocyte ratio; CAR: CRP to albumin ratio; CPR: CRP to platelet ratio.

Mortality

TotalN = 98

P

AliveN = 47

DiedN = 51

Age

58 (32–82)

64 (22–81)

61 (22–82)

0.013

Gender

Male

28 (59.6 %)

29 (56.9 %)

57 (58.2 %)

0.786

Female

19 (40.4 %)

22 (43.1 %)

41 (41.8 %)

TLC

10.0 (2.3–31.0)

12.6 (1.7–26.0)

11.6 (1.7–31.0)

0.041

ANC

7.9 (1.5–28.6)

11.3 (1.3–23.2)

9.9 (1.3–28.6)

0.028

ALC

1.0 (0.3–4.5)

1.0 (0.2–2.4)

1.0 (0.2–4.5)

0.275

NLR

7.9 (1.0–47.7)

13.7 (2.2–52.7)

11.2 (1.0–52.7)

0.006

Hb

12.9 (6.6–16.1)

12.4 (7.5–15.5)

12.8 (6.6–16.1)

0.335

Platelet

201 (15–607)

200 (38–466)

201 (15–607)

0.709

Ferritin

553 (143–1579)

1023 (234–2000)

855 (143–2000)

<0.001

CRP

57 (12–463)

138.0 (9.2–453.0)

104.5 (9.2–463.0)

<0.001

LDH

432 (226–1627)

567 (227–1319)

543 (226–1627)

<0.001

D-Dimer

0.6 (0.3–4.4)

0.9 (0.2–5.6)

0.8 (0.2–5.6)

<0.001

Cr.

0.80 (0.09–3.9)

1.00 (0.30–6.9)

0.90 (0.09–6.9)

0.242

Albumin

3.20 (2.07–4.30)

3.01 (1.90–4.50)

3.10 (1.90–4.50)

0.029

LOS, Days

10 (3–56)

8 (1–37)

9 (1–56)

0.158

CLR

70 (8.64–926)

139 (9.32–930)

91.37 (8.64–93)

<0.001

CAR

16.5 (3.3–144.7)

45.5 (2.0–197.0)

33.7 (2–197)

<0.001

CPR

318.40 (29.9–28937.5)

692.9 (44–3368.4)

470.65 (29.9–28937.5)

<0.001

ANDC

66.9 (30.7–153.3)

97.0 (37.8–160.9)

81.7 (30.7–160.9)

<0.001

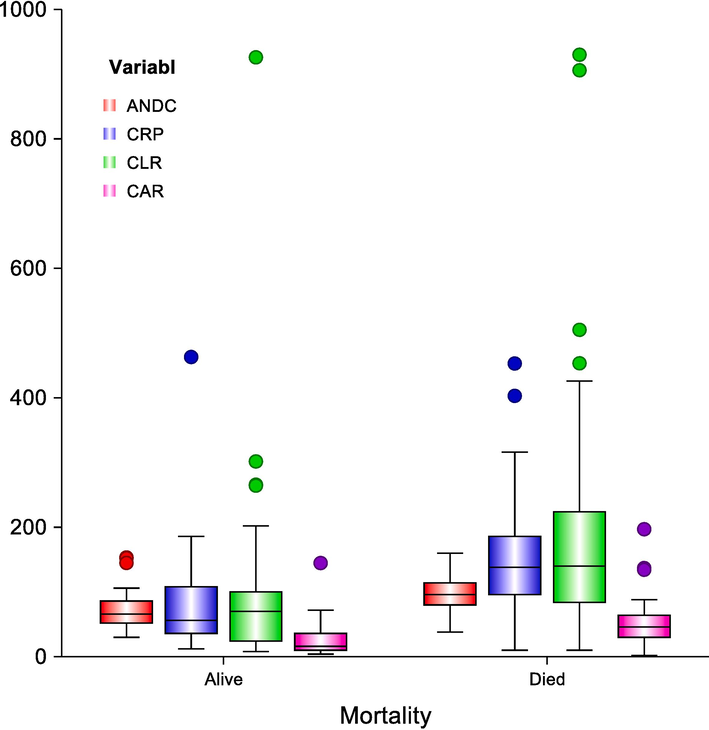

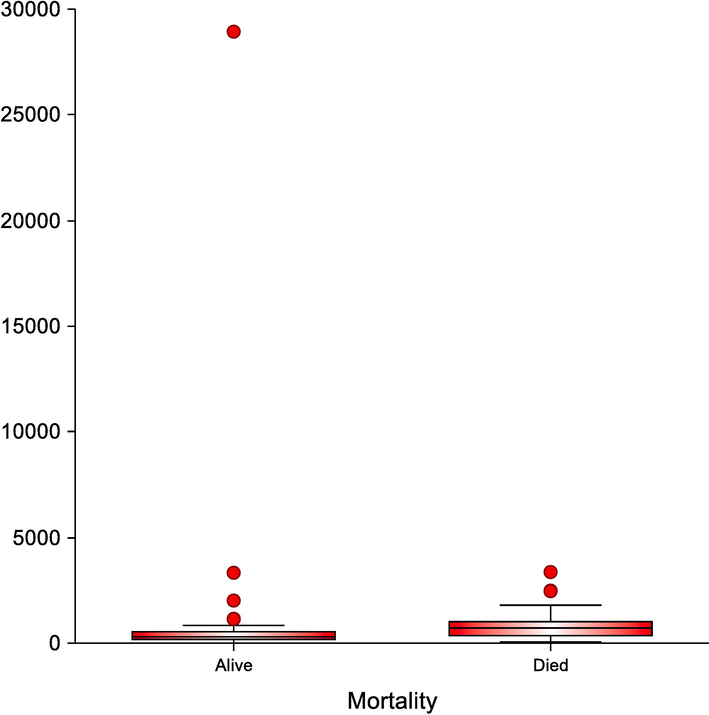

Moreover, a highly statistically significant difference regarding CRP levels, CAR, CPR, CLR, and ANDC was noted (0.032, <0.001, <0.001, <0.001, and < 0.001, respectively), Table 2, Fig. 1A, Fig. 1B.

Markers

Mortality

TotalN = 98

P

AliveN = 47

DiedN = 51

CRP Level

Low

8 (17.0 %)

2 (3.9 %)

10 (10.2 %)

0.032

High

39 (83.0 %)

49 (96.1 %)

88 (89.8 %)

CAR Level

Low

36 (76.6 %)

16 (31.4 %)

52 (53.1 %)

<0.001

High

11 (23.4 %)

35 (68.6 %)

46 (46.9 %)

CPR Level

Low

34 (72.3 %)

14 (27.5 %)

48 (49.0 %)

<0.001

High

13 (27.7 %)

37 (72.5 %)

50 (51.0 %)

CLR Level

Low

34 (72.3 %)

12 (23.5 %)

46 (46.9 %)

<0.001

High

13 (27.7 %)

39 (76.5 %)

52 (53.1 %)

ANDC Level

Low

28 (59.6 %)

6 (11.8 %)

34 (34.7 %)

<0.001

High

19 (40.4 %)

45 (88.2 %)

64 (65.3 %)

Box-plot diagram represents the range of ANDCscore, CRP, CLR, and CAR in the studied groups; the upper & lower line in each box represents the 75th& 25th percentile, respectively, while the line through each box indicates the median. Whiskers represent the range between the minimum and maximum values.

Box-plot diagram represents the range of CPR in the studied groups.

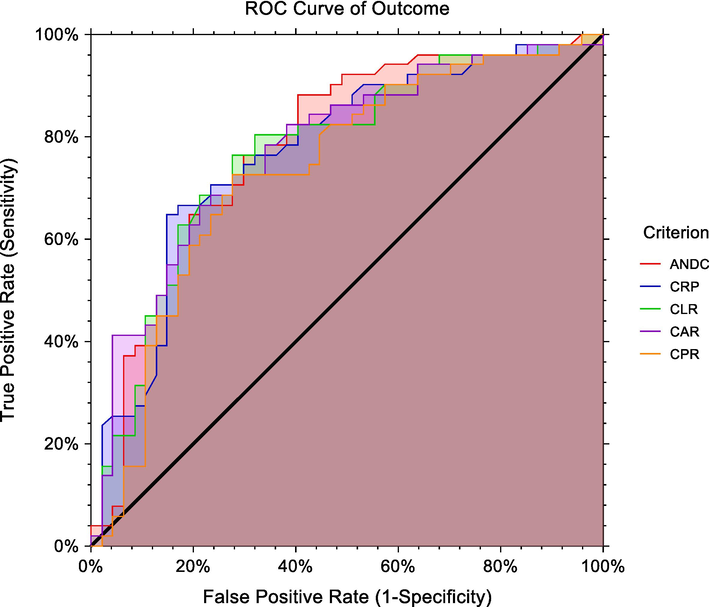

Our study showed that serum CRP level > 123 ng/ml, CAR > 36.77, CPR level > 462, and CLR > 84 had sensitivity; (64.71 %, 66.6 %, 72.5 %, and 76.4 %, respectively) and specificity; (85.1 %, 78.7 %, 72.3 %, and 72.3 % respectively) in mortality prediction. Meanwhile, the ANDC score was the most sensitive indicator (88.2 %) for mortality outcome, Fig. 2& Table 3. The 95%CI: 95% confidence interval, Positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV), Area under the ROC curve (AUC). CRP: c- reactive protein; CAR: c-reactive protein to albumin ratio; CPR: c-reactive protein to platelet ratio; CLR: c-reactive protein to lymphocyte ratio.

ROC curve of serum CRP, ANDC, CAR, CLR, and CPR levels markers for mortality in COVID-19 patients.

Cut-off

Sensitivity %

95 % CI

Specificity %

95 % CI

PPV

95 % CI

NPV

95 % CI

AUC

95 % CI

P

CRP

>123

64.71

50.1–––77.685.11

71.7–––93.882.5

69.8–––90.669

60.1–––76.70.772

0.677–––0.867<0.001

CAR

>36.77

66.67

52.1–––79.278.72

64.3–––89.377.3

65.5–––85.968.5

59.0–––76.70.778

0.683–––0.856<0.001

CPR

>462.7

72.55

58.3–––84.172.34

57.4–––84.474

63.5–––82.370.8

60.0–––79.70.736

0.634–––0.837<0.001

CLR

>84

76.47

62.5–––87.272.34

57.4–––84.475

64.8–––83.073.9

62.6–––82.70.772

0.677–––0.866<0.001

ANDC

>72.6

88.24

76.1–––95.659.57

44.3–––73.670.3

62.3–––77.382.4

68.0–––91.10.778

0.684–––0.873<0.001

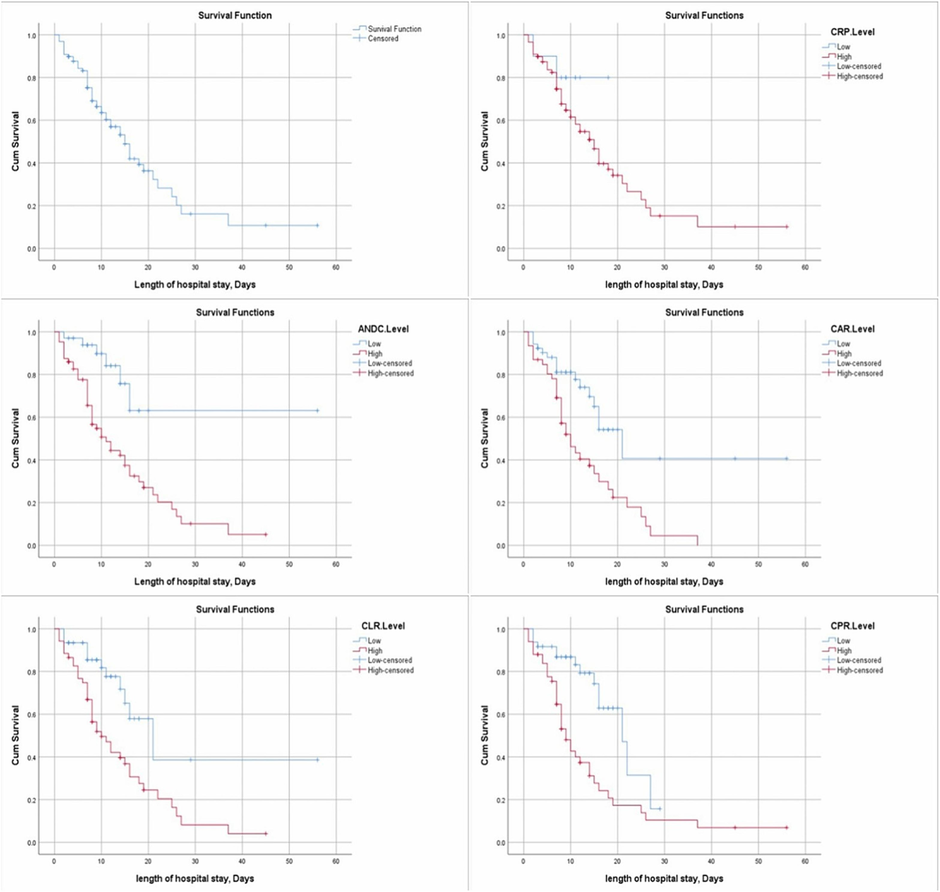

There was a significant difference in LOS between high and low levels of CAR, CPR, and CLR groups (p = 0.001, <0.001, 0.001; respectively), as well as a high level of ANDC score compared with a low-level group (p = 0.001). However, no significant difference in LOS was observed between high and low CRP (p = 0.224), Table 4, Fig. 3. NR: not reached; 95%CI: 95% confidence interval, variables compared by log-rank test. CRP: c-reactive protein; CAR: c-reactive protein to albumin ratio; CPR: c-reactive protein to platelet ratio; CLR: c-reactive protein to lymphocyte ratio. *Kaplan– Meier survival analysis.

Total

N

N of Events

Censored

N (%)

LOS, Days

ICU

Survival

Rate%

Sig.

Mean (95 % CI)

Median (95 % CI)

CRP Level

Low

10

2

8 (80.0 %)

15.3 (11.9–18.7)

NR

80.0 %

0.224

High

88

49

39 (44.3 %)

18.5 (13.9–23.0)

15.0 (11.7–18.3)

10.1 %

CAR Level

Low

52

16

36 (69.2 %)

30.3 (19.7–40.9)

21.0 (14.3–27.7)

40.6 %

0.001

High

46

35

11 (23.9 %)

13.0 (10.0–16.1)

10.0 (6.7–13.3)

0.0 %

CPR Level

Low

48

14

34 (70.8 %)

19.5 (16.2–22.8)

21.0 (15.2–26.8)

15.7 %

<0.001

High

50

37

13 (26.0 %)

14.2 (9.7–18.8)

9.0 (7.0–11.0)

6.9 %

CLR Level

Low

46

12

34 (73.9 %)

30.2 (17.2–43.1)

21.0 (12.1–29.9)

38.6 %

0.001

High

52

39

13 (25.0 %)

14.0 (10.6–17.4)

10.0 (6.1–13.9)

4.1 %

ANDC Level

Low

34

6

28 (82.4 %)

39.8 (27.8–51.7)

NR

63.1 %

0.001

High

64

45

19 (29.7 %)

14.6 (11.3–17.9)

11.0 (6.7–15.3)

5.1 %

Overall

98

51

47 (48.0 %)

19.1 (14.4–23.8)

15.0 (11.8–18.2)

6.3 %

Kaplan– Meier survival curves illustrating hospital survival time differences in all patients and within each category as regards CRP, ANDC, CAR, CLR, and CPR levels.

The effects of Age, Sex, CRP, CRP-derived inflammatory markers, ANDC level, Initial TLC, Ferritin, LDH, and D-Dimer on the likelihood of participants' mortality after ICU admission were investigated and ascertained by performing logistic regression. The univariate logistic regression analyses revealed that mortality was dependently associated with aging, CAR; CPR; CLR Levels, ANDC level, Ferritin, and LDH with H.R. [1.03 (1.01–1.06); 2.60 (1.44–4.71); 2.93 (1.58–5.46); 2.71 (1.42–5.19); 3.93 (1.67–9.26); 1.002 (1.001–1.003) and1.001 (0.999–1.002) respectively] and P-value was [0.008; 0.002;0.001,0.003;0.002; 0.001 and 0.004 respectively]. However, on multivariable Cox regression analysis, aging, CPR, and ANDC level were independently associated with mortality with H.R. [1.025 (1.002–1.050); 2.338 (1.189–4.599) and 2.896 (1.191–7.044)] and P-value was [0.034, 0.014 and 0.019 respectively], Table 5. The multivariate regression model entered all variables with P-value < 0.05 in univariate analysis.HR: hazard ratio; 95 %CI: 95 % confidence interval. Four multivariate cox regression models were constructed to avoid multicollinearity with the covariates. CRP: c-reactive protein to albumin ratio; CPR: c-reactive protein to platelet ratio; CLR: c-reactive protein to lymphocyte ratio;TLC: total leukocytic count; ANC: absolute neutrophil count; ALC: absolute lymphocyte count; NLR: neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio; Hb: hemoglobin; PLT: platelet; LDH: lactate dehydrogenase; Cr: creatinine.

Covariate

Univariate-Cox

Regression analysis

Multivariate-cox regression analysis

Model 1: Age, CARLevel, Ferritin, LDH

Model 2: Age, CPRLevel, Ferritin, LDH

Model 3: Age, CLRLevel, Ferritin, LDH

Model 4: ANDCLevel, Ferritin, LDH

Sig.

HR (95 % CI for HR)Sig.

HR (95 % CI for HR)Sig.

HR (95 % CI for HR)Sig.

HR (95 % CI for HR)Sig.

HR (95 % CI for HR)

Age

0.008

1.03 (1.01–1.06)0.065

1.022 (0.999–1.046)0.034

1.025 (1.002–1.050)0.044

1.024 (1.001–1.047)

Gender

0.951

0.98 (0.56–1.73)

CRPLevel

0.248

2.31 (0.56–9.58)

CARLevel

0.002

2.60 (1.44–4.71)0.120

1.732 (0.866–3.462)

CPRLevel

0.001

2.93 (1.58–5.46)

0.014

2.338 (1.189–4.599)

CLRLevel

0.003

2.71 (1.42–5.19)

0.051

2.036 (0.996–4.163)

ANDCLevel

0.002

3.93 (1.67–9.26)

0.019

2.896 (1.191–7.044)

TLC

0.408

1.02 (0.98–1.06)

ANC

0.340

1.02 (0.98–1.07)

ALC

0.145

0.69 (0.41–1.14)

NLR

0.083

1.02 (1.00–1.05)

Hb

0.928

0.99 (0.87–1.13)

PLT

0.097

1.00 (1.00–1.00)

Ferritin

0.001

1.002 (1.001–1.003)0.258

1.001 (1.000–1.002)0.359

1.000 (0.999–1.001)0.302

1.001 (1.000–1.002)0.103

1.001 (1.000–1.002)

LDH

0.004

1.001 (0.999–1.002)0.325

1.001 (0.999–1.002)0.274

1.001 (0.999–1.002)0.286

1.001 (0.999–1.002)0.357

1.001 (0.999–1.002)

D-Dimer

0.570

1.09 (0.82–1.44)

Cr.

0.113

1.18 (0.96–1.45)

Albumin

0.278

0.69 (0.35–1.36)

5 Discussion

Some tests can be performed in labs or imaging devices that may indicate the typical signs of COVID-19 and its consequences or risk factors for problems (Azkur et al., 2020 Jul). Complete blood count lymphopenia, eosinopenia, and neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio of less than 3.13 are connected to increased severity and a poorer prognosis (Chen et al., 2020; Vabret et al., 2020; Wynants et al., 2020). Higher CRP, ferritin, PCT, LDH and D-dimer are all associated with a more severe illness and a less favorable prognosis than lower levels of these markers in most studies.

Developing a reliable prediction tool to forecast how the illness would manifest itself clinically may greatly assist in risk stratification, clinical decision-making, and rational resource optimization. They are essential to prevent potentially life-threatening side effects and, eventually, lessen the severity of the disease's impact. Unfortunately, the scores and nomograms that have been made public up to this point are much more challenging to understand due to the inclusion of a significant increase in the number of criteria (some up to 23) (Bal et al., 2021).

In the present study, our objective was to evaluate the predictive usefulness of the aforementioned score and parameters in adult covid-19 patients necessitating hospital admission.

We used these four factors to develop a scoring system called the ANDC score for predicting mortality. On the other hand, it is essential to keep in mind that it forecasts death rates rather than the need for NIV, IVM, or ICU admission. As a result, it may be most effective at its extremes, such as when it gives doctors the confidence to release patients with low mortality ratings or prompts early talks about treatment escalation with patients who need oxygen.

CRP is a protein that may be used to locate or monitor ailments that produce inflammation. Viral infections are the most prevalent disorders that decrease the number of lymphocytes in the blood, and CRP can be used to detect or monitor these conditions. These findings support our earlier conclusion that CLR and NLR are both significant predictors of mortality. Although both NLR and LCR could identify seriously unwell patients and those critically ill, Bal and colleagues discovered that LCR was more effective than NLR (Tonduangu, et al., 2021). Compared to NLR, LCR showed a superior ability to discriminate between thoughtfully and critically sick individuals (Liu et al., 2020). The viral load of the SARS-CoV-2 virus is likely responsible for explaining our findings. This viral load has been linked to CRP and lymphopenia and has been demonstrated to correlate well with the severity of the disease (Kalabin et al., 2021).

The current analysis found that CAR was considerably more remarkable in the group of patients who passed away compared to those who survived, consistent with previous findings from past investigations (Wiedermann, 2021). Albumin is found in high concentrations in human blood; hypoalbuminemia, which is low albumin levels, is often caused by inflammation and is linked to worse outcomes across various illnesses (Poudel et al., 2021). This helps explain why the dying patients had a significantly elevated CAR level. Hypoalbuminemia in Covid-19 patients results from the complex interaction of systemic inflammation with successively increased capillary permeability and redistribution of albumin to interstitial fluids. This conclusion was supported by previously published data that revealed an association of severity of illness and greater D-dimer values; a prognostic mortality clue (Yao et al., 2020; Meini et al., 2021). According to the findings of this study, a higher level of D-dimer was significantly associated with a greater risk of passing away. When there is a systemic infection, both the extrinsic coagulation route and the contact coagulation pathway are active (Wool and Miller, 2021). The coagulation cascade activation, which may have been brought on by viremia, superinfection, cytokine storm, or organ failure, resulted in increased D-dimer levels in patients who later passed away. Disseminated intravascular coagulopathy may be a factor in COVID-19 (Fan et al., 2006), which might explain why D-dimer levels were more significant in individuals who passed away from the disease.

Our findings revealed that CRP, CAR, and CLR all had a high AUC for predicting mortality (0.772, 95 percent CI: 0.677–0.867 for CRP; 0.778, 95 percent CI: 0.683–0.856 for CAR; 0.772, 95 percent CI: 0.677–0.866 for CLR) and that using CAR and CLR boosted sensitivity at the expense of specificity. On the other hand, The NLR alone may predict mortality with a reasonably high AUC (0.764, 95 percent confidence interval (CI): 0.659–0.850), but it only has a sensitivity of 56.52 percent. This was determined via observational research and meta-analyses. The combination of CRP and the NLR combined led to an area under the curve (AUC) value of 0.804 (95 percent confidence interval [CI]: 0.702–0.883), as well as a considerable improvement in sensitivity from 56.52 percent to 73.92 percent, at the expense of a loss in specificity (Kalabin et al., 2021). Both the LCR and the NLR were able to identify critically ill patients from severe patients, with the CLR having a higher ROC AUC than the NLR (Tonduangu et al., 2021). This information lends credence to our hypotheses and reveals that published research supports them. On the other hand, Tonduangu and colleagues discovered that CLR was the only significant predictor of mortality out of the investigated variables (CRP level, lymphocyte level, and CLR level) (Liu et al., 2020).

With a cutoff score of > 72.6, we stratified patients according to the score into low score group and high score group. The ANDC score was 66.9 (30.7–153.3) in live Patients and 97.0 (37.8–160.9) in the deceased one, with a positive predictive value of the scoring system (70.3 %), and the negative predictive value was 82.4 % which showed good Discrimination using ROC curves (AUC:0.778;95 % CI; p < 0.001) as an AUC ROC value over 0.75 represents good clinical Discrimination (Liu et al., 2021).

One retrospective study used the ANDC score on 301 patients with COVID-19 to assess its prognostic usefulness in predicting hospital mortality. They found that the ANDC score provided a quantitative tool for identifying individuals with a high mortality risk on admission (AUC 0.912) and directing clinical care (Huang et al., 2020).

One significant disadvantage is that its use may need to be more practical in low- and middle-income nations (LMICs).

Unfortunately, in LMICs, where physiological scores may be more practical, restricted access to virological testing and laboratory facilities may limit their utility.

In conclusion: The utility of the ANDC score and the CRP-derived inflammatory indicators readily increases the prediction of identifying patients at high mortality risk.

Ethical consideration:

The current study was conducted in accordance with the strict guidelines and regulation such as Declaration of Helsinki.

The study was conducted according to the protocol approved by the Review Board of the Faculty of Medicine of Zagazig University IRB#9567–1-6–2022.

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects and their legal guardian(s).

Acknowledgment

We would like to acknowledge staff members of Zagazig University hospitals, who suffered a lot during the COVID-19 pandemic. This paper is wholehearted to them, as their dynamic share to knowledge about COVID-19 made it possible. The authors extend their appreciation to the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSP2024R418), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Sleep quality among Healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on medical errors: Kuwait Experience. Turk Thorac J.. 2021;2:142-148.

- [Google Scholar]

- Better outcome of COVID-19-positive kidney transplant recipients during the unremitting stage with optimized anticoagulation and immunosuppression. Clin Transplant.. 2021;35(6):e14297.

- [Google Scholar]

- Immune response to SARS-CoV-2 and mechanisms of immunopathological changes in COVID-19. Allergy. 2020 Jul;75(7):1564-1581.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lymphocyte-to-C-reactive protein ratio may serve as an effective biomarker to determine COVID-19 disease severity. Turk J Biochem. 2021;46(1):21-26.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and immunological features of severe and moderate coronavirus disease 2019. J Clin Invest.. 2020;130(5):2620-2629.

- [Google Scholar]

- Understanding receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. CJEM. 2006;8(1):19-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497-506.

- [Google Scholar]

- Does C reactive protein/albumin ratio have prognostic value in patients with COVID-19? J Infect Dev Ctries.. 2021;15(8):1086-1093.

- [Google Scholar]

- Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(13):1199-1207.

- [Google Scholar]

- Combined use of the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and CRP to predict 7-day disease severity in 84 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 pneumonia: a retrospective cohort study. Ann Transl Med.. 2020;8(10):635.

- [Google Scholar]

- Correlation between relative Nasopharyngeal virus RNA load and lymphocyte count disease severity in patients with COVID-19. Viral Immunol.. 2021;34(5):330-335.

- [Google Scholar]

- Use of hydroxychloroquine in patients with COVID-19: a retrospective observational study. Turk Thorac J.. 2021;22(1):62-66.

- [Google Scholar]

- Management protocol of COVID 19 patients by Ministry of Health and population, Egypt Version 1.5. 2021. Egyptian Guidelines of COVID-19 Treatment. https://mti.edu.eg/634335.

- D-Dimer as Biomarker for Early prediction of clinical outcomes in patients with severe invasive infections due to Streptococcus pneumoniae and Neisseria meningitidis. Front Med (lausanne). 2021;8:627830

- [Google Scholar]

- The novel coronavirus originating in Wuhan, China: challenges for Global Health governance. JAMA. 2020;323(8):709-710.

- [Google Scholar]

- D-dimer as a biomarker for assessment of COVID-19 prognosis: D-dimer levels on admission and its role in predicting disease outcome in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. PLoS One. 2021;16(8):e0256744.

- [Google Scholar]

- Crems network clinical research in emergency medicine and sepsis clr. 2021: Prognostic value of C-reactive protein to lymphocyte ratio (CLR) in Emergency department patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. J Pers Med. 2021;11(12):1274.

- [Google Scholar]

- Immunology of COVID-19: current state of the science. Immunity. 2020;52(6):910-941. Sinai Immunology Review Project

- [Google Scholar]

- ANDC: an early warning score to predict mortality risk for patients with coronavirus disease 2019. J Transl Med.. 2020;18(1):328.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hypoalbuminemia as surrogate and culprit of infections. Int J Mol Sci.. 2021;22(9):4496.

- [Google Scholar]

- The impact of COVID-19 disease on platelets and coagulation. Pathobiology. 2021;88(1):15-27.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prediction models for diagnosis and prognosis of covid-19: systematic review and critical appraisal. BMJ. 2020;369:m1328

- [Google Scholar]

- D-dimer as a biomarker for disease severity and mortality in COVID-19 patients: a case-control study. J Intensive Care.. 2020;8:49.

- [Google Scholar]

- Criteria and potential predictors of severity in patients with COVID-19. Egypt J Bronchol. 2022;16:11.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054-1062.

- [Google Scholar]

Appendix A

Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2024.103176.

Appendix A

Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article: