Translate this page into:

Novel material from immobilization of magnesium oxide and cetyl trimethyl ammonium bromide nanoparticles onto waterworks sludge for removing methylene blue from aqueous solution

⁎Corresponding author. ayad.faesal@coeng.uobaghdad.edu.iq (Ayad A.H. Faisal),

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Utilizing the waterworks sludge byproduct in the treatment of wastewater contained methylene blue dye is one approach that has been taken in an effort to lessen the difficulties that are associated with managing such byproduct. The prime aim of this work is manufacturing of novel sorbent from co-precipitation of magnesium oxide nanoparticles on the surfaces of waterworks sludge in the existence of cetyl trimethyl ammonium bromide surfactant. Surfactant 0.04 g/50 mL, dose of sludge 2 g/50 mL, and pH 12 were the most efficient preparation parameters to remove 75.31% of adopted dye. The adsorption studies were conducted under various conditions of contact time (0–240 min), concentration of dye (10–300 mg/L), sorbent mass (0.05–1.5 g), and solution pH (3–12). The best values of batch parameters were identical to the highest percentages of contaminant removal. Results proved that the magnesium oxide nanoparticles are attached to the sludge surfaces. Freundlich and pseudo-second-order models have perfectly described sorption results with 59.92 mg/g maximum sorption capacity. The breakthrough curves can be accurately described by the Bohart-Adams model. The outputs of continuous tests have been paved the way for future usage of the prepared sorbent in the field permeable reactive barrier technology.

Keywords

Waterworks sludge-CTAB

Methylene blue

Magnesium oxide

Sludge

Adsorption

1 Introduction

Cosmetic, leather, plastics, paper, pharmaceutical, and textile effluents consist of a variety of highly toxic and carcinogenic chemicals (Al Juboury et al., 2020; Sonal et al., 2018). Dyes are aromatic chemicals that pose harmful effects on a variety of microorganisms and can cause substantial damage to their catalytic characteristics (Arslan-Alaton and Caglayan, 2005; Duan et al., 2010).

The oxygen of healthy aquatic system can be reduced by a variety of physicochemical processes that can take place on dyes in water dumped into groundwater. Methylene blue (MB) is a necessary element in textile dyes, cotton, and wood. Its utilization produces variety of illnesses in both human and animal eyes. As a consequence of its major influence on the quality of receiving waterways, it is necessary to treat the effluent containing such colors (Shah et al., 2013).

Adsorption is an effective approach that has demonstrated its success when compared to other wastewater treatment technologies (Naushad et al., 2016). It has a number of benefits, including the following: it can be used to eliminate harmful substances; efficient at eliminating organic pollutants; it's design and operation are adaptable; and requires less space than a biological system. Due to its high adsorption capacity, activated carbon (AC) is the common adsorbent applied to clean dye-wastewater. Consequently, it is considered the best option for remediating of textile-wastewater. High cost of AC in combination with problems associated with its regeneration are main causes that lead to restrict the usage of such sorbent. As a result, a new direction in scientific research was established with the goal of finding efficient, inexpensive reactive materials that could serve as alternatives to AC (Faisal et al., 2014; Faisal and Nassir, 2016; Rashid and Faisal, 2019, 2018). Clay, coffee grounds, fly ash, peat, sludge, and agricultural wastes are used to remediate dye-wastewater (Sonal et al., 2018). Furthermore, non-traditional materials like biomass, algal, rice husk, fruit peels, and sewage sludge have been evaluated in the rehabilitation of solutions contaminated with MB (Al-Hashimi et al., 2021; Al Juboury et al., 2020; Faisal et al., 2022, 2018).

Previous researches (Birniwa et al., 2022; Hossain et al., 2020; Kumar et al., 2022) provided an overview to explain the main topics like: (1) the general characteristics of cationic dyes; (2) the art state in the field of dye treatment; (3) the sorption of such dyes by various bio-sorbents; and (4) the factors that influence the sorption process of dyes. Also, MB dye removal efficiency was evaluated using AC made from oil palm mesocarp fibers and bunches of empty fruit (Baloo et al., 2021). A novel, inexpensive biochar made from sewage sludge was tested for its ability to absorb color from batik industrial effluent (Al-Mahbashi et al., 2022). To remove the carmine dye from an aqueous solution, chitin nano-whiskers were synthesized and used as a green adsorbent (Meshkat et al., 2019).

Billions tons of waterworks sludge (WS) can release in each year from works associated to purify of water for drinking in Europe only, and this number is subject to rise significantly in the coming decades. Several countries also dispose sludge straightforward into the river, creating turbulence and raising the cost of cleaning the water to make it drinkable. As a result, water corporations aim to find low-cost solutions to the sludge disposal like recycled it as sorbent. Hence, the significance of this work is; 1) using WS as solid matrix to immobilize the magnesium oxide (MgO) nanoparticles in the presence of cetyl trimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB) to produce the novel sorbent known as “WS-CMgO” for eliminating of cationic MB dye; 2) determining the best values for the operational parameters that are necessary for treatment process in the synthesis, batch, and continuous stages.

2 Experimental work

2.1 Materials

The WS was taken from the Al-Wahda plant of water supply, Baghdad, Iraq. It was dried for three days, and sizes from 63 μm to 1 mm with geometric mean size of 250 μm was chosen using sieve analysis. The sludge was further examined by TEM and SEM analyses. The sludge has a low hydraulic conductivity of 0.0221 cm/s, and previous studies showed that it can cause a blocking during continuous flow. This sludge's permeability starts to increase to be higher or equal than that one of the nearby aquifer in order to be used as a permeable material in the column. The results demonstrated substantial hydraulic conductivity when mixing sludge in a certain ratio with coarse sand. Sand has been used as a 1.7 to 3.15 mm particle size distribution and a hydraulic conductivity of 0.941 cm/s. However, it was found that the ideal percentage was 1:19, which may offer acceptable permeability of 0.983 cm/s.

2.2 Contaminant

At room temperature, 1000 mg/L of contaminated water was obtained through dissolution of one-gram MB (supplied from HIMEDIA, India) in 1L water. The prepared solution can dilute to prepare the desired concentration of MB dye, and the solution’s pH modified by 0.1 M hydrochloric acid or sodium hydroxide.

2.3 Sorbent preparation

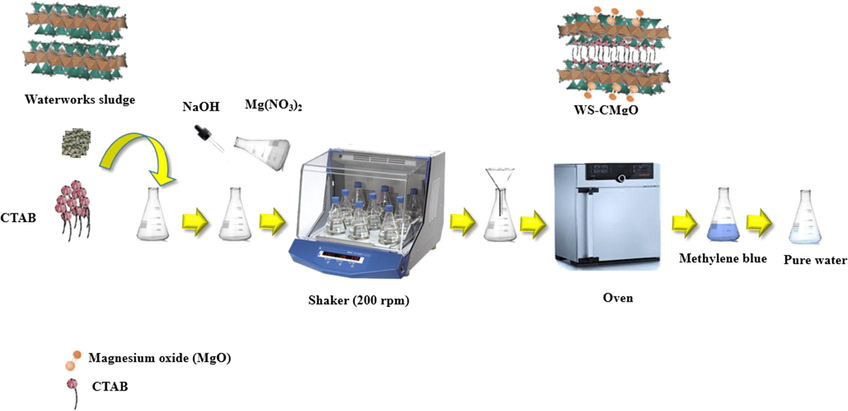

The experimental method depicted in Fig. 1 was used to create the modified WS by expanding and homogenizing 5 g of virgin sludge with 50 mL of water in a flask for three hours at 200 rpm. Furthermore, CTAB surfactant supplied by Sigma Aldrich Chemise, Germany with amount of (0.02–0.2 g) was tested to specify the suitable quantity required for the highest removal rate. After being shaken for three hours, the modified WS was filtered, washed numerous times with distilled water to get rid of salts, and dried at 105 °C. This sludge was then mixed with 50 ml of water containing 2 g of magnesium nitrate (Mg(NO3)2) which purchased from SD Fine-Chem. Limited, India. The solution was dried for four hours at 105 °C after being agitated for three hours. The solid particles produced by the aforementioned method were further dried for 24 h at 105 °C to be suitable for treatment tests (Phuengprasop et al., 2011). Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) “ achieved by XFlash 5010; Bruker AXS Microanalysis, Berlin, Germany” can use to identify the surface morphology of WS-CMgO and virgin WS.

Experimental methodology for preparation of waterworks sludge modified by cetyl trimethyl ammonium bromide and magnesium oxide as well as its interaction with MB dye.

2.4 Sorption tests

The water samples (with volume 50 mL) of 50 mg MB/L have been introduced into 250 mL volumetric flasks for the sorption experiment. A certain sludge dose of 0.05 to 1.5 g was mixed with this water in separate flasks. The flasks were agitated with speed of 200 rpm by shaker type “Edmund Buhler SM25, Germany”. The treated water was filtered by JIAO JIE 102 papers to separate the adsorbent from the solution; however, an ultraviolet–visible (UV/VIS) spectrophotometer “Shimadzu Model: UV/VIS-1650″ was used to determine the MB concentration at 663 nm maximum wavelength of absorption. In order to determine the best contact time, water samples were collected on a regular basis during experiments lasting for period not exceeding 240 min. More research was done to see how the initial pH of the water, which ranges from 3 to 12, affects the effectiveness of MB removal at the concentration of 50 mg/L.

2.5 Column study

Tests of column to eliminate MB from simulated polluted water have been used to evaluate the composite sorbent's reactivity. An acrylic cylinder with 2.5 cm diameter and 50 cm height represents the experimental setup applied to represent the dye transport in one-dimension. The sampling port is 35 cm above the bottom of the cylinder. The coarse sand was mixed with prepared WS-CMgO in proportion of 1:19 and mixture must be packed in the column for continuous tests. However, only coarse sand was used in one test to determine its role in the treatment process. A peristaltic pump was used to inject water upward from the bed bottom to prevent air from becoming trapped. The MB-contaminated water was then applied to the fixed bed through storage, control valves, and hydraulic difference to monitor the MB concentration in the collected effluent samples.

3 Modeling of outputs

The adsorption isotherm models (Table 1) used in the current investigation to characterize the interaction between WS-CMgO and MB are fully described in previous studies like (Foo and Hameed, 2010; Hamdaoui and Naffrechoux, 2007; Ho et al., 2002). This table is also presented the kinetic models used in this work to understand how quickly the molecules of contaminant will be eliminated from aqueous solutions.

Model

Form

Isotherm

Freundlich

Langmuir

Kinetic

Pseudo first order

Pseudo second order

Breakthrough

Bohart-Adams (1920)

Yan (2001)

Belter-Cussler-Hu (1988)

For continuous mode operation, the breakthrough curves (C/Co versus elapsed time) are measured experimentally at certain locations and then fitted with empirical and semi analytical approximations explained in Table 1. Such curves can utilize effectively in the designing of sorption bed on the scale of field. Basic concepts and assumptions for models of breakthrough are explained extensively in the familiar works like (Chatterjee and Schiewer, 2011; Nwabanne and Igbokwe, 2012).

4 Results and discussion

4.1 Preparation of sorbent

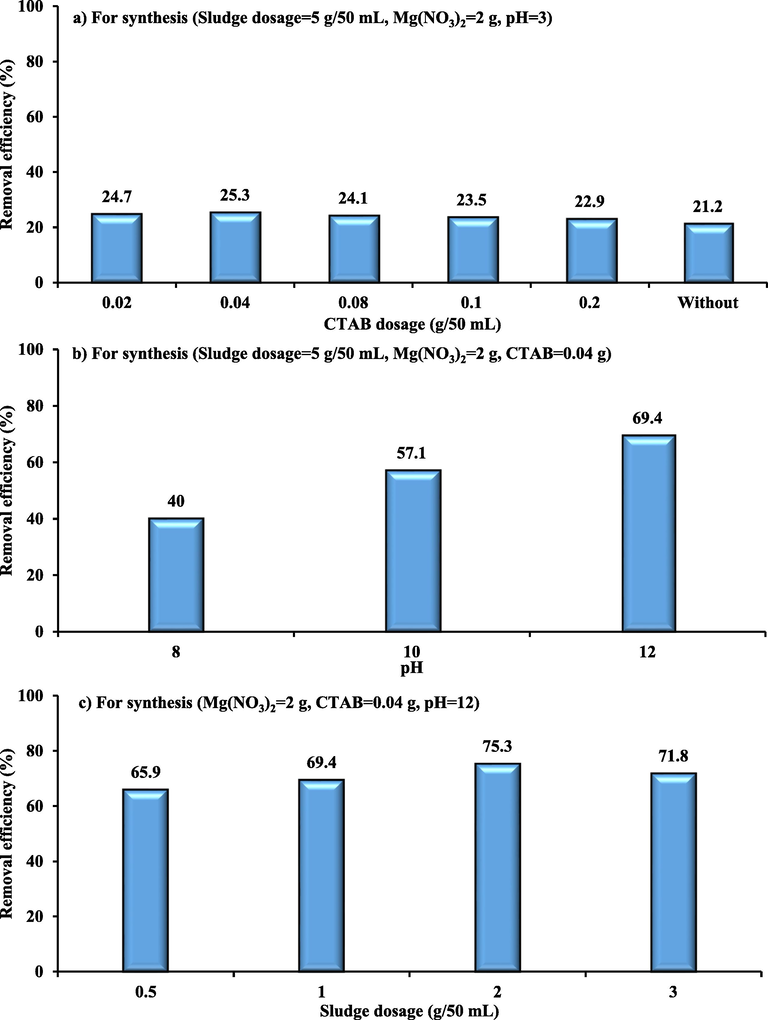

The effect of the surface modification on the efficacy of eliminating MB has been the subject of present experiments. The incorporation of a surfactant dosage (g CTAB) with virgin WS was the base to create the modified sludge. The percentages of MB eliminated from the aqueous phase as a function of CTAB quantity were shown in Fig. 2(a) for conditions at 25 °C (Co = 10 mg/L, time = 3 h, pH = 7, mass of coated sludge = 0.1 g/50 mL, speed = 200 rpm). The clearance of MB reduced as the quantity of surfactant (CTAB) rose because the cations of MB and CTAB-WS formed a repulsive electrostatic interaction (Faisal et al., 2022). The CTAB mass 0.04 g was the best quantity for WS modification since it produced the maximum MB removal performance. The removal effectiveness of MB using WS from aqueous systems was 21.2% under the same conditions. Also, it was found that the modified WS had 1.194-times the adsorption capacity of WS, this is due to the increase in spacing of the WS layer after modification, as well as, the hydrophilic surface of the WS was transformed to hydrophobic to boost adsorptive capacity (Faisal et al., 2022).

Effect of a) CTAB b) pH and c) waterworks sludge dosage on the MB removal efficiency by WS-CMgO for sorption conditions (time = 3 h, Co = 10 mg/L, sorbent dosage = 0.1 g/50 mL, pH 7, speed 200 rpm).

Using various pH values for an aqueous solution containing a particular concentration of Mg(NO3)2, the effect of CTAB-WS coated with magnesium oxide (WS-CMgO) on the percentage of MB removed was examined, as depicted in Fig. 2(b). The prepared sorbent's ability to remove MB noticeably improves as the solution pH rises from 3 in Fig. 2(a) to 8, 10, and 12 in Fig. 2(b) during the synthesis stage. This is because a greater amount of magnesium oxide can precipitate on the surfaces of sludge particles at a higher pH. No significant change in the dye removal efficiency was recognized for pH = 13; consequently, WS-CMgO can be produced at a pH of 12. The amount of WS (Fig. 2(c)) used throughout the coating process was then adjusted between 0.5 and 3 g per 50 mL with 2 g of Mg(NO3)2. The MB removal percentage was improved by increasing the dosage of CTAB-WS from 0.5 to 2 g. After completing the preparation procedure, wash can be used to remove the uncoated magnesium oxide. CTAB-WS mass of 2 g was recommended to finish the coating process.

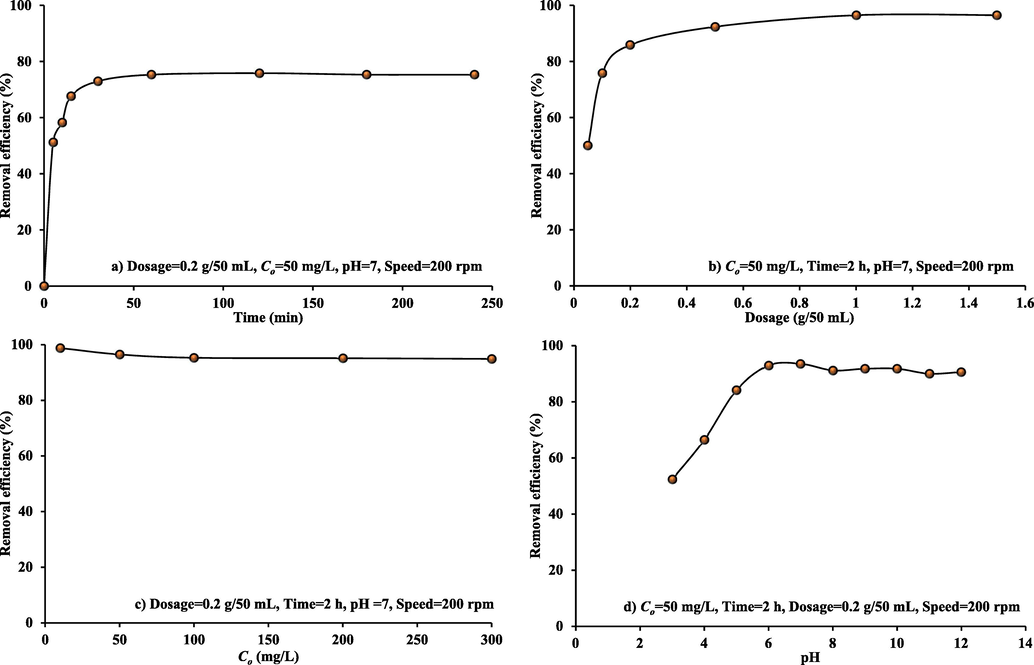

4.2 Conditions of batch tests

Fig. 3(a) represents the relationship between MB removal efficiencies and contact time when utilizing prepared WS-CMgO. At ambient temperature, the test conditions were Co = 50 mg/L, pH = 7, agitation speed = 200 rpm, and WS-CMgO dose = 0.2 g/50 mL. During the first 30 min, MB uptake rate was extremely rapid and; then, slowed down beyond this time. Exhausting the available active sites may lead to this reduction. However, the dye removal was not significantly affected by an additional increase in contact time. The figure also indicated that 60 min is a sufficient time to reach the equilibrium concentration that stabilized at fixed value for up to four hours (Ahmed and Faisal, 2023; Faisal et al., 2021).

Effect of operational conditions in batch study on MB dye removal from aqueous solution by prepared sorbent at temperature of 25 °C.

The addition of 0.05 to 1.5 g of WS-CMgO to 50 mL of dye solution was used to investigate the relationship between sorbent dosage and MB sorption (Fig. 3(b)). For a given initial MB concentration, dye removal can increase with higher dosage until 1 g. This was to be expected because there were more vacant sites with a higher dose of sorbent in the solution. This figure proves that the dye removal sets in beyond 1 g of sorbent. As a result, even after an additional dose of adsorbent is added, there is no change in the amount of MB that is bound to the sorbent or present in solution. However, the change in sorbent dosage from 0.2 to 1 g did not significantly increase removal efficiency (less than 10%); therefore, the suitable dosage for subsequent batch experiments can be 0.2 g.

Fig. 3(c) indicates that the mean elimination fell from 96 to 94% when the Co increased from 10 to 300 mg/L. Because of the entire interaction between the empty sites and MB, the percentage removal was high at lower concentrations. However, the decrease in efficiency at large concentrations might be due to a depletion of these sites (Al Juboury et al., 2020).

Fig. 3(d) shows the MB elimination for WS-CMgO adsorbents at various pH range (3–12) under specified experimental conditions. This figure indicated that the removal rate of MB by WS-CMgO had raised due to change of pH from 3 to 7. With increasing pH, the removal of MB by WS-CMgO adsorbents increases from 52.37 to 93.54%. As a consequence, the highest MB dye uptake was found at pH 7. This result is consistent with the previous findings for MB adsorption on wood shavings, wasted tea leaves, and sunflower seed hull (Janoš et al., 2003; Sulaymon and Abdul-Hameed, 2010). The availability of additional hydrogen ions that competed with the MB for vacant sites may the cause for reduction of MB adsorption at acidic pH. Electrostatic attraction causes a decrease in positively charged sites and an increase in negatively charged sites, favoring MB adsorption. As the pH increases from 7 to 12, slight decrease in MB removal can be observed due to the development of a hydroxyl complex between the adsorbent and the dye.

The MB removal onto WS-CMgO sorbent under experimental conditions of 0.2 g/50 mL sorbent, a contact time of 2 h, and 50 mg/L Co is depicted in Fig. 3(d). Removal of adopted dye increases from 52.37 to 93.54% when the pH changes from 3 to 7, respectively. For this range, there is competition between high protons and MB molecules for binding locations on the prepared sorbent. This implies that the electrostatic attraction causes a reduction in positive charged sites and an increase in adversely charged destinations, leaning toward MB adsorption. The formation of a hydroxyl complex between the sorbent and the dye will result in a slight decrease in the amount of color that can be removed after pH 7 is reached. This behavior is in line with previous findings (Janoš et al., 2003) regarding MB adsorption onto sunflower seed hull, wasted tea leaves, and wood shavings.

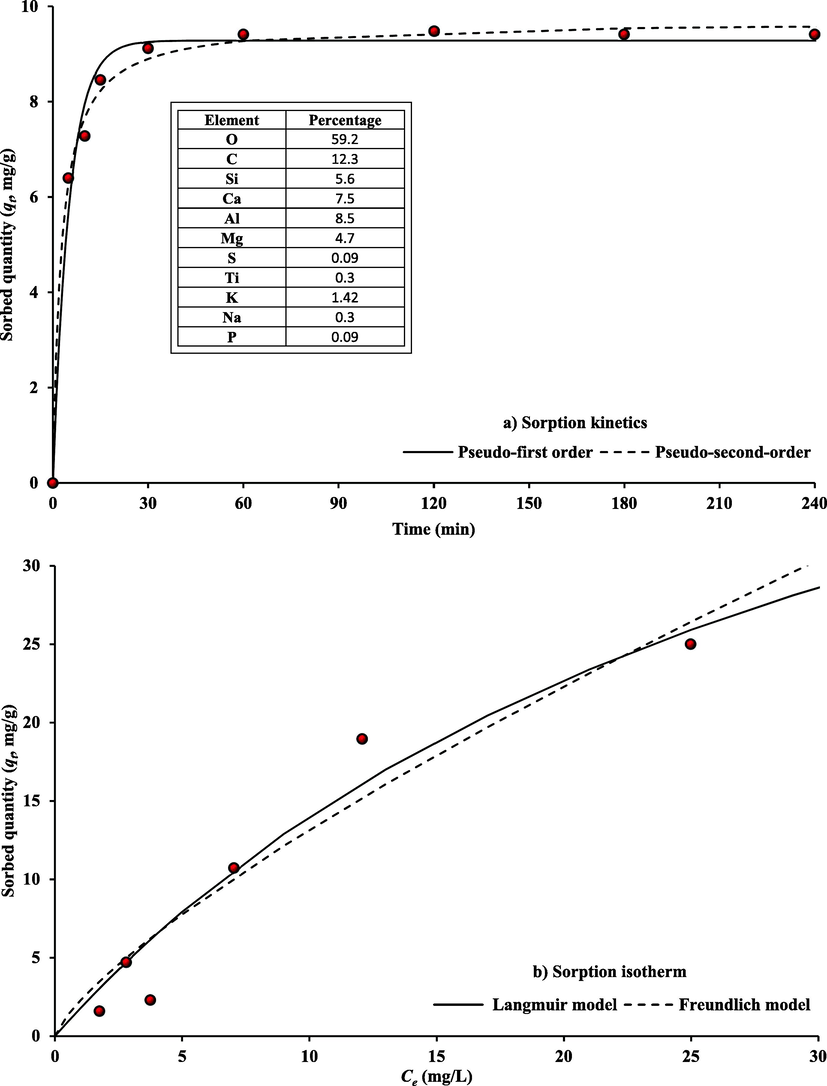

4.3 Sorption kinetics

“Microsoft Excel 2016′s, Solver” tool determines the kinetic model parameters (Table 2). The kinetic test was achieved at the best possible conditions; dosage of 0.2 g of WS-CMgO in 50 mL of the aqueous phase, Co = 50 mg/L and 200 rpm of agitation. The results (Fig. 4(a)) demonstrate that the elimination of MB by WS-CMgO is represented by a pseudo-second-order equation with “coefficient of determination, R2″ of 0.99 and ”sum of squared errors, SSE“ of 0.30. Consequently, the sorption process is controlled by chemical forces, and the adsorption mechanism is “chemisorption”.

Model

Parameter

Value

Sorption isotherm

Freundlich

KF (mg/g)(L/mg)1/n

2.282

n

1.314

R2

0.985

Langmuir

qm (mg/g)

59.92

b (L/mg)

0.030

R2

0.940

Sorption kinetic

Pseudo-first order

qe

9.282

k1

0.194

R2

0.986

SSE

1.059

Pseudo-second-order

qe

9.681

k2

0.039

R2

0.996

SSE

0.309

Models predictions for sorption kinetic and equilibrium isotherm of MB onto WS-CMgO in comparison with experimental measurements.

4.4 Sorption isotherm

The experimental measurements related to the MB dye captured by WS-CMgO particles (qe) and its quantity remaining in the aqueous solution (Ce) at equilibrium were formulated using the sorption models listed in Table 1. The Excel program's “Solver” option was utilized to complete the formulation process. The results of fitting for isothermal measurements are shown in Table 2 by the constants of sorption models and statistical measures that show how well these models and measurements match. In Fig. 4(b), predictions from the Freundlich and Langmuir models are plotted alongside sorption results. Because the Freundlich model has a higher coefficient of determination (R2 = 0.985), it is better suited to describe sorption data than the Langmuir model. The maximum sorption capacity (qm) of MB onto WS-CMgO is 59.92 mg/g, according to the Langmuir model. This value is comparable with maximum sorption capacities that calculated for other types of sorbents from previous studies. For example, these capacities are equal to 9.8, 20.5, and 135.13 mg/g onto activated alumina (Iida et al., 2004), orange peel (Jalil et al., 2010), and non-washed digestate (Yao et al., 2020) respectively.

4.5 Characterization of sorbent

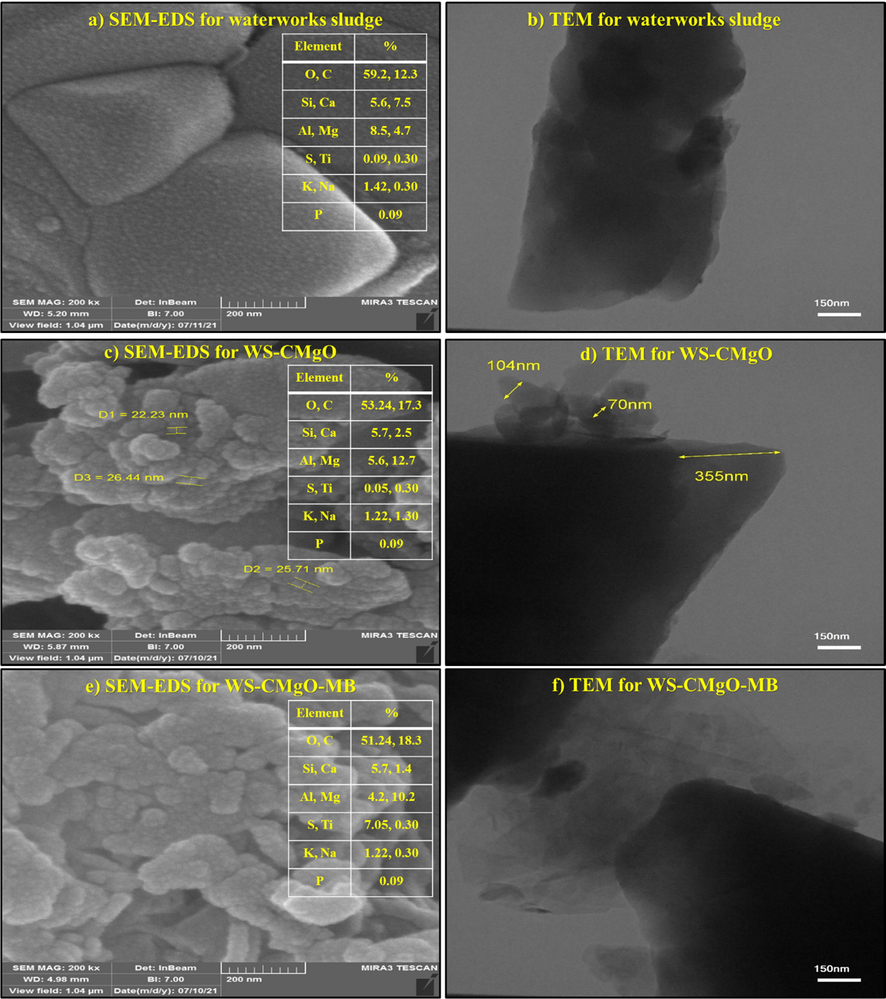

Fig. 5 illustrates the morphologies of WS, WS-CMgO, and WS-CMgO-MB sorbents. The morphologies of WS and WS-CMgO are appeared to be random before contact with the MB dye. However, this figure demonstrates that the MgO nanoparticles are being attached to the prepared sorbent's surface beyond dye sorption. Fig. 5 depicts the TEM images of WS, WS-CMgO, and WS-CMgO-MB sorbents. Waterworks sludge TEM images have mean size of around 355 nm and a generally of hexagonal structure. The WS-CMgO TEM images revealed that the nanoparticles of the amorphous boron (70–100 nm in size) have been uniformly coated within the observed area. In addition, the TEM test performed on the prepared sorbent following its interaction with MB molecules revealed that the sorbent particles' sizes varied significantly.

The SEM-EDS and TEM analyses for waterworks sludge, WC-CMgO, and WS-CMgO-MB.

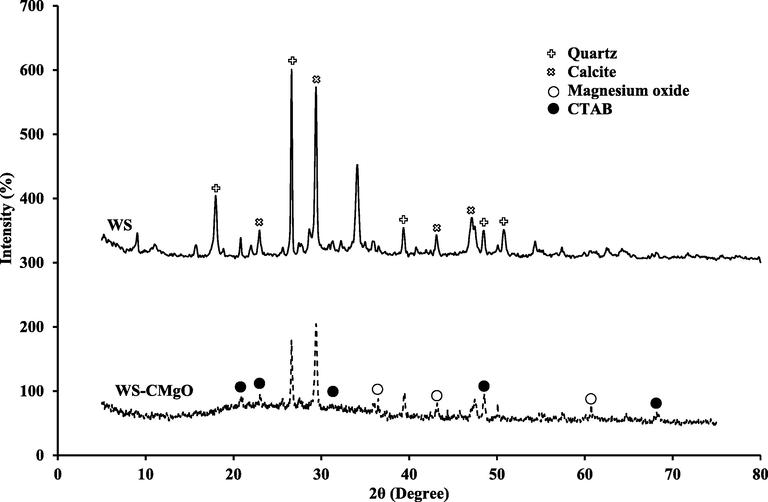

Fig. 5 illustrates the existence of C, Mg, O, Na, Al, Ca, N, Ti, Si, S, N, and P components in multi-elemental EDS for the corresponding sorbents before and after the sorption process. Fig. 5 proves the increasing of Mg and C intensity in the sorbent compound, which is related to the existence of MgO and CTAB. Additionally, the increase in S elements following the sorption process shows that the MB dye on the coated sorbent has been removed. Using X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns, the crystalline structures of WS and sludge coated with MgO and CTAB nanoparticles are shown in Fig. 6. Based on the observed peaks, calcite and silica are the primary components of WS while MgO and CTAB can be recognized on the prepared sorbent after coating process.

XRD patterns of the waterworks sludge and WS-CMgO.

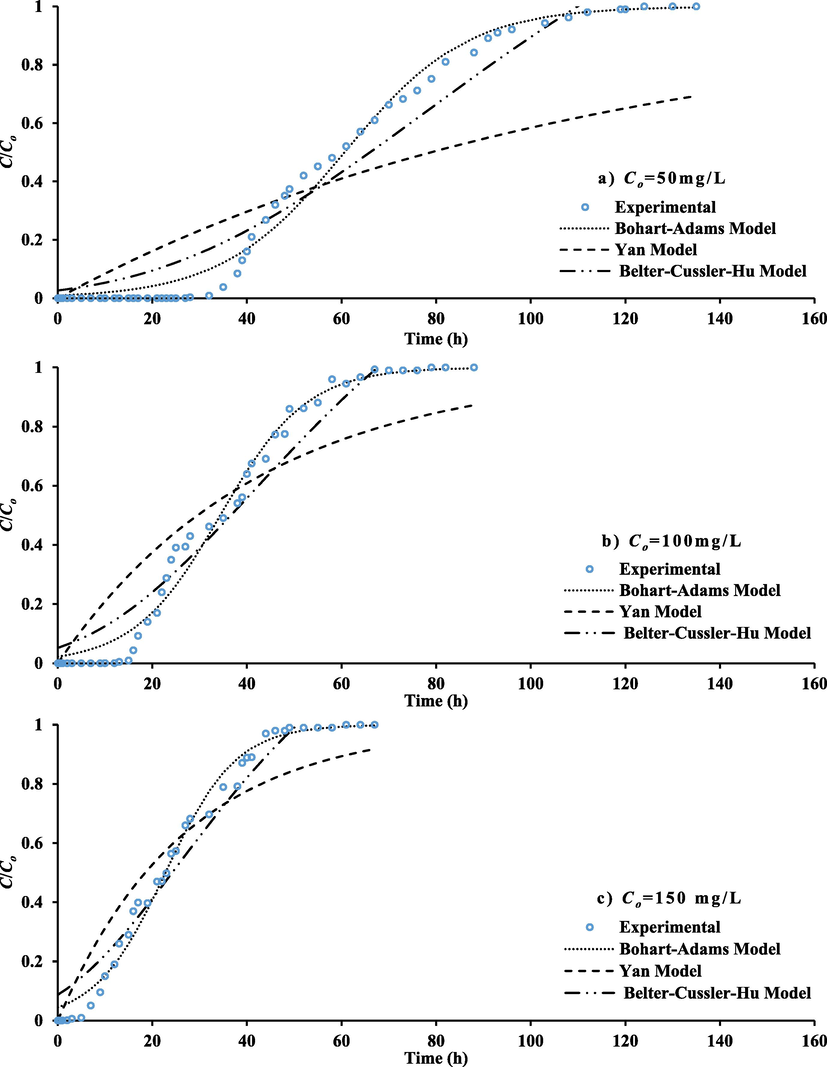

4.6 Models for breakthrough curves

Fig. 7 plots the propagation of MB dye front for sampling port located at 35 cm depth of the prepared sorbent bed under the various values of inlet concentration (50, 100 and 150 mg/L) at water flowrate of 5 mL/min. Higher gradient of concentration can result in an obvious increment in the steepness of plotted curves; so, shorter period requires to saturate with target dye. Definitely, the higher driving force can generate from greater gradient of concentration and this will accelerate the transportation of contaminant molecules towards the sorbent; so, they will be rapidly exhausted (Liao et al., 2013). The longevity of the packed bed can specify from breakthrough curves through identification of breakthrough or saturation time identical to 5 or 90% of C/Co respectively. Fig. 7 proved that the breakthrough time is 36 h for 50 mg/L inlet concentration. This time was reduced to be 16 and 7 h for 100 and 150 mg/L respectively.

Propagation of MB dye plume in terms of normalized concentration along the packed bed as a function of time.

Models of Bohart-Adams, Yan, and Belter-Cussler-Hu were applied for simulating the measured breakthrough curves (Fig. 7) under various inlet concentration for prepared sorbent at 35 cm. The output of fitting process (like parameters of models with measures of goodness listed in Table 3) have been determined by “Solver option in Microsoft Excel-2016” for nonlinear regression. The calculated parameters proved that the increase of sorbent mass can be accompanied with clear increase in the MB uptake capacity. More suitable model for representation of breakthrough curves is represented the target task where the equation of this model can apply to find the values of saturation and breakthrough times which identical to the C/Co of 90 and 5% respectively. Table 3 and Fig. 7 signified that the Bohart-Adams model is well described the experimental measurements with R2 greater than 0.981 and SSE less than 0.113.

Model

Parameter

Influent concentration (mg/L)

50

100

150

Bohart-Adams

KCo

0.077

0.110

0.134

KNoZ/U

4.680

3.768

3.062

R2

0.991

0.986

0.990

SSE

0.097

0.113

0.073

Belter-Cussler-Hu

to

109.832

67.635

50.627

σ

0.451

0.515

0.585

R2

0.950

0.949

0.958

SSE

0.495

0.431

0.306

Yan

0.001QC/qoM

0.000097

0.000110

0.000176

91.307

213.069

213.071

R2

0.906

0.918

0.958

SSE

0.940

1.034

0.455

5 Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to make a new sorbent by combining CTAB surfactant and magnesium oxide nanoparticles with WS, a byproduct of water supply treatment plant. The removal of MB dye from an aqueous solution was chosen as a measure of the prepared sorbent's performance. It has been demonstrated that pH 12, CTAB dosage of 0.04 g, sludge dosage of 2 g/50 mL, and Mg(NO3)2 = 2 g are the ideal manufacturing conditions for this kind of sorbent, ensuring a dye removal rate of more than 92%. The prepared sorbent has qm of 59.92 mg/g, indicating that it can effectively remove MB from contaminated water, according to batch tests (at best operational conditions of pH 7, sorbent dosage 0.2 g/50 mL, and contact time 2 h for initial dye concentration of 50 mg/L). For sorption measurements, an effective description of the pseudo-second-order model was provided; so that the removal process can be controlled by chemical forces. However, compared to the Langmuir relationship, the Freundlich model is superior at describing equilibrium sorption measurements. It was found that the Bohart-Adams model was very good at explaining how the breakthrough curve moves along the packed column. Continuous tests proved that the manufactured sorbent can effectively limit the migration of dye front; consequently, it is recommended to apply the WS-CMgO sorbent in the permeable reactive barrier technology on a field scale.

Acknowledgement

We would like to gratefully acknowledge the technical support of Environmental Engineering Department / University of Baghdad provided during the present work. One of the authors (Ayman A. Ghfar) is grateful to the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSP2023R407), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia for the financial support.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Precipitation of calcium-aluminum-cetyltrimethylammonium bromide nanoparticles on the sand to generate novel adsorbent for eliminating of amoxicillin from aquatic environment. Alexandria Eng. J.. 2023;66:489-503.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis of composite sorbent for the treatment of aqueous solutions contaminated with methylene blue dye. Water Sci. Technol. 2020

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A comprehensive review for groundwater contamination and remediation: occurrence, migration and adsorption modelling. Molecules. 2021;26:5913.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bench-scale fixed-bed column study for the removal of dye-contaminated effluent using sewage-sludge-based biochar. Sustainability. 2022;14:6484.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ozonation of Procaine Penicillin G formulation effluent Part I: Process optimization and kinetics. Chemosphere. 2005;59:31-39.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Adsorptive removal of methylene blue and acid orange 10 dyes from aqueous solutions using oil palm wastes-derived activated carbons. Alexandria Eng. J.. 2021;60:5611-5629.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Birniwa, A.H., Abubakar, A.S., Mahmud, H.N.M.E., Kutty, S.R.M., Jagaba, A.H., Abdullahi, S.S., Zango, Z.U., 2022. Application of Agricultural Wastes for Cationic Dyes Removal from Wastewater. pp. 239–274. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-2832-1_9.

- Biosorption of cadmium(II) ions by citrus peels in a packed bed column: Effect of process parameters and comparison of different breakthrough curve models. CLEAN - Soil, Air, Water. 2011;39:874-881.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis of a novel flocculant on the basis of crosslinked Konjac glucomannan-graft-polyacrylamide-co-sodium xanthate and its application in removal of Cu2+ ion. Carbohydr. Polym.. 2010;80:436-441.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Iron permeable reactive barrier for removal of lead from contaminated groundwater. J. Eng.. 2014;20:29-46.

- [Google Scholar]

- Removal of ammoniacal nitrogen from contaminated groundwater using waste foundry sand in the permeable reactive barrier. Desalin. WATER Treat.. 2021;230:227-239.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Modeling the removal of cadmium ions from aqueous solutions onto olive pips using neural network technique. Al-Khwarizmi Eng. J.. 2016;12:1-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- A review of permeable reactive barrier as passive sustainable technology for groundwater remediation. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol.. 2018;15:1123-1138.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Precipitation of (Mg/Fe-CTAB) - layered double hydroxide nanoparticles onto sewage sludge for producing novel sorbent to remove Congo red and methylene blue dyes from aqueous environment. Chemosphere. 2022;291:132693

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Insights into the modeling of adsorption isotherm systems. Chem. Eng. J.. 2010;156:2-10.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Modeling of adsorption isotherms of phenol and chlorophenols onto granular activated carbon Part II. Models with more than two parameters. J. Hazard. Mater.. 2007;147:401-411.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ho, Y.S., Porter, J.F., McKay, G., 2002. Equilibrium isotherm studies for the sorption of divalent metal ions onto peat: Copper, nickel and lead single component systems. Water. Air. Soil Pollut. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021304828010.

- Waste materials for wastewater treatment and waste adsorbents for biofuel and cement supplement applications: A critical review. J. Clean. Prod.. 2020;255:120261

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sonochemically enhanced adsorption and degradation of methyl orange with activated aluminas. Ultrasonics. 2004;42:635-639.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Adsorption of methyl orange from aqueous solution onto calcined Lapindo volcanic mud. J. Hazard. Mater.. 2010;181:755-762.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, J., Jatoi, A.S., Mazari, S.A., Ali, E.Y., Hossain, N., Abro, R., Mubarak, N.M., Sabzoi, N., 2022. Advanced green nanocomposite materials for wastewater treatment, in: Sustainable Nanotechnology for Environmental Remediation. Elsevier, pp. 297–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-824547-7.00015-1

- Adsorption of tetracycline and chloramphenicol in aqueous solutions by bamboo charcoal: A batch and fixed-bed column study. Chem. Eng. J.. 2013;228:496-505.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Investigation of Carmine dye removal by green chitin nanowhiskers adsorbent. Emerg. Sci. J.. 2019;3:187-194.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Naushad, M., Ahamad, T., Sharma, G., Ala’a, H., Albadarin, A.B., Alam, M.M., ALOthman, Z.A., Alshehri, S.M., Ghfar, A.A., 2016. Synthesis and characterization of a new starch/SnO 2 nanocomposite for efficient adsorption of toxic Hg 2+ metal ion. Chem. Eng. J. 300, 306–316. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2016.04.084.

- Nwabanne, J.T., Igbokwe, P.K., 2012. Adsorption Performance of Packed Bed Column for the removal of Lead (ii) using oil Palm Fibre. Int. J. Appl. Sci. Technol.

- Removal of heavy metal ions by iron oxide coated sewage sludge. J. Hazard. Mater.. 2011;186:502-507.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Removal of dissolved cadmium ions from contaminated wastewater using raw scrap zero-valent iron and zero valent aluminum as locally available and inexpensive sorbent wastes. Iraqi J. Chem. Pet. Eng.. 2018;19:39-45.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Removal of dissolved trivalent chromium ions from contaminated wastewater using locally available raw scrap iron-aluminum waste. Al-Khwarizmi Eng. J.. 2019;15:134-143.

- [Google Scholar]

- Steam regeneration of adsorbents: an experimental and technical review. J. Chem. Sci.. 2013;2:1078-1088.

- [Google Scholar]

- Decolorization of reactive dye Remazol Brilliant Blue R by zirconium oxychloride as a novel coagulant: optimization through response surface methodology. Water Sci. Technol.. 2018;78:379-389.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sulaymon, H.A., Abdul-Hameed, H.M., 2010. Competitive adsorption of cadmium lead and mercury ions onto activated carbon in batch adsorber. J. Int. Environ. Appl. Sci.

- Study of the digestate as an innovative and low-cost adsorbent for the removal of dyes in wastewater. Processes. 2020;8:852.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Appendix A

Supplementary material

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2023.102751.

Appendix A

Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article: