Translate this page into:

Nano-based herbal Mahkota Dewa (Phaleria macrocarpa) for pre-eclampsia: A histological study on placental and blood changes

⁎Corresponding author at: Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas HKBP Nommensen, Medan 20232, Indonesia. leosimanjuntak@uhn.ac.id (Leo Jumadi Simanjuntak)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Background

Phaleria macrocarpa, a medicinal plant native to Indonesia, can potentially manage oxidative stress and inflammation—key factors in pre-eclampsia. This study investigates its efficacy as a complementary therapy for pre-eclampsia.

Materials and Methods

Sixty Wistar rats (30 male, 30 females; 120–180 g) were housed at Universitas Sumatera Utara. After a two-week acclimatization, confirmed pregnant female rats were divided into six groups: C- (normal), C+ (pre-eclampsia, untreated), C1 (Nifedipine 10 mg/kg BW), T1 (Mahkota Dewa 180 mg/kg BW), T2 (360 mg/kg BW), and T3 (720 mg/kg BW). Treatment groups received daily injections of Prednisone (1.5 mg/kg BW) and 6 % NaCl for 14 days. Pre-eclampsia was confirmed with blood pressure readings of 140/90 mmHg. Blood samples were analyzed for superoxide dismutase (SOD), malondialdehyde (MDA), VEGF, and sFlt-1. Placental samples were assessed for caspase-3, −8, and −10 expression using immunohistochemistry.

Results

The nano-herbal formulation significantly reduced oxidative stress (lower MDA, higher SOD), restored angiogenic balance (lower sFlt-1, higher VEGF), and decreased apoptosis markers (caspase-3, −8, −10).

Conclusion

Nano-herbal Mahkota Dewa shows promise as a therapeutic option for pre-eclampsia. It effectively reduces oxidative stress, improves angiogenic balance, and provides protection against placental apoptosis.

Keywords

Nano-herbal

Mahkota Dewa

Pre-eclampsia

Oxidative stress

Angiogenic balance

Placental apoptosis

- C-

-

Negative control group

- C+

-

Positive control group

- C1

-

pre-eclampsia with Nifedipine 10 mg/kg BW group

- T1

-

Pre-eclampsia with 180 mg/kg BW of Mahkota Dewa group

- T2

-

Pre-eclampsia with 360 mg/kg BW of Mahkota Dewa group

- T3

-

Pre-eclampsia with 720 mg/kg BW of Mahkota Dewa group

- SOD

-

Superoxide dismutase

- MDA

-

Malondialdehyde

- VEGF

-

Vascular endothelial growth factor

- sFlt-1

-

Soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1

- HELLP

-

Hemolysis, Elevated Liver enzymes, and Low Platelet

- PE

-

Pre-eclampsia

- EC

-

Endothelial Cell

- FV

-

Fetal Vessel

- ELISA

-

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

- IHC

-

Immunohistochemistry

- PlGF

-

Placental Growth Factor

- BW

-

Body Weight

- NK

-

Natural Killer

Abbreviations

1 Introduction

Pre-eclampsia (PE) continues to be a major challenge in obstetrics, characterized by unclear etiology and complex pathophysiology, earning it the label of a 'disease of theories.' It impacts between 2 % and 8 % of pregnancies worldwide, leading to more than 50,000 maternal deaths and 500,000 fetal fatalities each year (Karrar et al., 2024). In Indonesia, PE accounts for 6–10 % of pregnancies and approximately 20 % of maternal deaths (Aryanti et al., 2022). PE also leads to severe neonatal complications, including prematurity, low birth weight, and increased neonatal mortality (Chang et al., 2023). Long-term effects on mothers include chronic hypertension and cardiovascular diseases. Current treatments, such as anti-hypertensive drugs (methyldopa, labetalol, nifedipine), help manage symptoms but fail to address placental dysfunction or endothelial disturbances and may pose risks to both mother and child. Preventive interventions like low-dose aspirin and calcium offer limited and inconsistent efficacy (Sakowicz et al., 2023). Premature delivery remains the only definitive cure but carries significant risks for neonatal health. This highlights the urgent need for novel treatments targeting endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and apoptosis.

Phytochemicals have shown promise in enhancing therapies for Pre-eclampsia. Earlier research has explored a range of plant species such as Euterpe oleracea, Punica granatum, Thymus schimperi, Vitis vinifera, and Moringa oleifera for their potential benefits in managing PE (Ożarowski et al., 2021; Situmorang et al., 2021). Phaleria macrocarpa (Mahkota Dewa), an Indonesian medicinal plant, has been traditionally used to treat high blood pressure and blood sugar levels (Mustapha et al., 2017). Scientifically, it has demonstrated antimicrobial (Lestari et al., 2023), blood sugar-lowering (Azad & Sulaiman, 2020; Mia et al., 2023; Easmin et al., 2024), anti-hypercholesterolemic (Adeloye et al., 2020), vasodilatory (Rizal et al., 2020), anti-inflammatory (Agustin et al., 2023), improve blood parameters such as leukocytes, erythrocytes, hemoglobin, hematocrit, and lymphocytes (Rumahorbo et al., 2024a), and antioxidant properties (Chaves et al., 2020). Additionally, it has shown potential in tissue repair (Sulistyoning Suharto et al., 2021), suppression of endometriosis (Maharani et al., 2021), and immunomodulation (Ahmad et al., 2023).

The antioxidant compounds in Mahkota Dewa neutralize oxidative stress by reducing reactive oxygen species (ROS) and free radicals. Its anti-inflammatory properties reduce placental inflammation (Christina et al., 2021), while its vasodilatory effects enhance blood flow to the placenta by promoting nitric oxide production (Rizal et al., 2020). In this study, the nano-formulation of Mahkota Dewa was processed using high-energy milling to improve its bioavailability and absorption. Biomarkers such as malondialdehyde (MDA), superoxide dismutase (SOD), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 (sFlt-1), and caspases-3, −8, and −10 were evaluated to evaluate the formulation's effects on oxidative stress, angiogenesis, and apoptosis. This approach underscores Mahkota Dewa's potential as a natural therapeutic solution for managing pre-eclampsia.

2 Materials and method

2.1 Chemicals, substances, and reagents

This study utilized ELISA and immunohistochemistry (IHC) techniques to assess the expression of specific biomarkers. The following ELISA kits were employed: MDA Assay Kit (ab238537), CheKine™ SOD Activity Kit (MBS9718960), VEGFR-2 ELISA Kit (MBS702919), and sFlt-1 ELISA Kit (MBS2601616). For IHC staining, antibodies used included Biotin Anti-Pro Caspase-3 (ab204632), Rabbit Anti-Caspase-8 (MBS2539398), and Rabbit Anti-Caspase-10 (MBS9401526).

2.2 Nano-based herbal Mahkota Dewa preparation

A total of 5 kg of Phaleria macrocarpa (Mahkota Dewa) fruit was collected from Simalungun, North Sumatra, Indonesia, and authenticated by Prof. Dr. Nursahara Pasaribu, M.Sc., at the Medanense Botanical Herbarium (registration number 114/MEDA/2023). After washing and air-drying for three weeks, the fruit was pulverized into coarse powder. A mechanical grinder produced nano-sized particles by grinding 2.5 g of powder with a 2 M HCl activator solution. Grinding durations were set to 3, 6, and 9 h, maintaining a material-to-ball mass ratio 1:20. The procedure for this work followed the method described by Rumahorbo et al. (2024b).

2.3 Management of animals and experimental design

Thirty Wistar albino rats (Rattus norvegicus) weighing 120–180 g were obtained from the Faculty of Pharmacy, Universitas Sumatera Utara. After a two-week acclimatization period, pairs of five rats per cage were mated, and pregnancy was confirmed via daily vaginal smears.

Five pregnant rats were assigned to the control group (C-), receiving no treatment. The remaining rats were induced with pre-eclampsia by administering 1.5 mg/kg BW of prednisone subdermally and 0.5 mL of 6 % saline daily from the second week of gestation. On day 15, the rats were divided into five groups: untreated positive control (C + ), control treated with Nifedipine (10 mg/kg BW) (C1), and three groups receiving nano-based herbal Mahkota Dewa at doses of 180 mg/kg BW (T1), 360 mg/kg BW (T2), or 720 mg/kg BW (T3) for one month. The grouping in this study follows the format and terminology used in previous research (Simanjuntak and Rumahorbo, 2024) to maintain consistency of results and data comparison. Rats had unlimited access to water and were fed a diet of ground corn or pellets. The Mahkota Dewa dosages were selected based on prior toxicological studies (Simanjuntak & Rumahorbo, 2022; Rumahorbo et al., 2023). The study received ethical approval from the Universitas Sumatera Utara Animal Research Ethics Committee and followed both ARRIVE guidelines and the EU Directive on animal research.

2.4 Measurement of MDA, SOD, VEGF, and sFlt-1 by ELISA

Whole blood was centrifuged at 2000–3000 rpm for 20 min to obtain the supernatant. ELISA assays were performed by adding 100 µL of standard solution and 50 µL of diluent to wells, followed by serial dilutions across the plate. The microplate was incubated at 37 °C for 30 min or overnight at 4 °C. After incubation, wells were washed five times with wash solution (1 mL in 29 mL distilled water). A blocking buffer was added and incubated for 60 min at 37 °C or overnight at 4 °C. Next, 10 µL of sample and 40 µL of diluent were added to the wells and incubated at room temperature for 120 min. Subsequently, 100 µL of biotinylated antibody was added, followed by incubation at 37 °C for 60 min and washing. ABC solution (100 µL) was added and incubated for 30 min at 37 °C, followed by another wash. Then, 90 µL of HRP-conjugate and 90 µL of TMB were added and incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. To halt the reaction, 100 µL of stop solution was added, and the optical density (OD) was determined at 450 nm with an ELISA reader. MDA, SOD, VEGF, and sFlt-1 levels were measured in triplicate.

2.5 Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Placental tissue apoptosis was assessed using IHC to detect caspase-3, caspase-8, and caspase-10. Paraffin-embedded placental sections (4–6 µm) were deparaffinized in xylene, rehydrated through a graded ethanol series, and treated with peroxidase-blocking and pre-diluted blocking serum. The primary antibodies were applied to the sections and incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies. Tissues were treated with peroxidase and DAB chromogen for visualization. Counterstaining was done with hematoxylin and eosin, and the slides were examined under a light microscope at 400x magnification. Brown staining was indicative of caspase expression. This procedure was similarly applied for caspase-8 and caspase-10 detection.

2.6 Statistical analysis

Quantitative data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics 25 for Windows. One-way ANOVA assessed significant differences between groups, with statistical significance set at P < 0.05 at a 95 % confidence interval. For non-normally distributed data, the Kruskal-Wallis test was used.

3 Result

3.1 Levels of MDA, SOD, VEGF, and sFlt-1

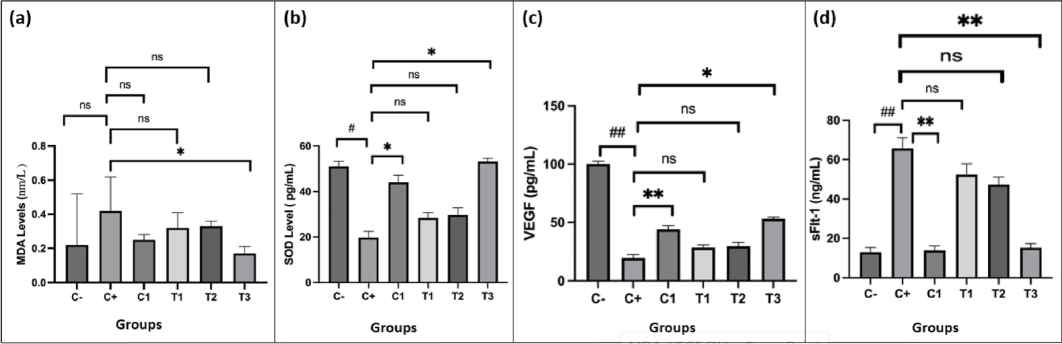

Fig. 1 (a-d) illustrates the levels of MDA (Fig. 1a), SOD (Fig. 1b), VEGF (Fig. 1c), and sFlt-1 (Fig. 1d). Elevated MDA levels indicate increased oxidative stress, while higher SOD levels suggest reduced oxidative stress. Significant differences in MDA and SOD levels were observed between the control (C-) and positive control (C + ), as well as between C + and treatment groups C1 and T3 (Fig. 1a and 1b). In terms of angiogenesis, sFlt-1, a VEGF antagonist, showed significant differences compared to both control groups (Fig. 1c). Elevated sFlt-1 levels in the C + group correlated with decreased VEGF levels, highlighting its role in inhibiting the interaction between VEGF and PlGF. Variations in VEGF and sFlt-1 levels were significant among the C+, C1, and T3 groups (Fig. 1c and 1d). The T1 group exhibited a substantial difference from C + only in sFlt-1, with no notable change in VEGF levels.

Effect of nano-based herbal Mahkota Dewa on the levels of MDA (a), SOD (b), VEGF (c), and sFlt-1 (d). #p < 0.05 vs. C-, ##p < 0.01 vs. C-, *p < 0.05 vs. C+, **p < 0.01 vs. C+, ns = non-significant.

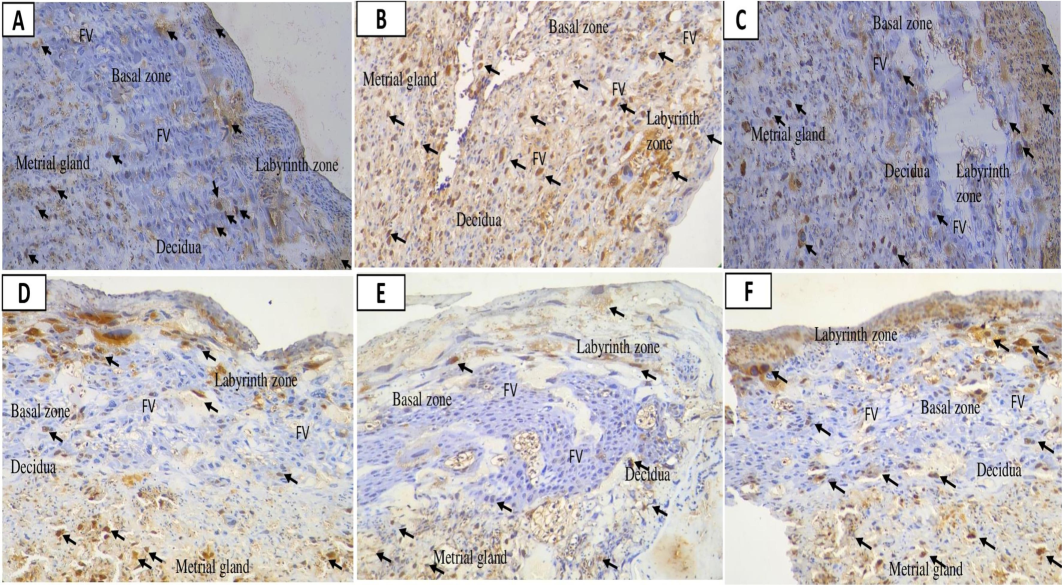

3.2 Expression of caspase-3 on placental

Analysis of rat placentas revealed that caspase-3 levels were lower in those treated with Mahkota Dewa (360 mg/kg BW) compared to Nifedipine (10 mg/kg BW). Mahkota Dewa effectively reduced caspase-3 expression across doses ranging from 180 to 720 mg/kg BW, with the most significant reduction observed at 360 mg/kg. The Kruskal-Wallis test indicated significant differences among groups (Table 1), while the Mann-Whitney test revealed differences between the positive control (C + ) and the other groups (p < 0.05, p = 0.010). Notably, groups T1 and T2 demonstrated significant reductions compared to the positive control, whereas T3 did not. The highest caspase-3 expression was observed in the C + group, while the lowest was in T2. However, levels in these groups did not reach those of the negative control (Fig. 2). Caspase-3, marked by dark brown staining, was absent in the labyrinthine area of the positive control, possibly due to staining damage. It was detected in the zona labyrinth, metrial gland, and decidua but rarely in the basal zone, except in the positive control group.

Groups

Mean ± SD

Kruskal-Wallis

p-value (Mann-Whitney)

C-

C+

C1

T1

T2

T3

C-

102.25 ± 4.82

0.00

0.020

0.020

0.030

0.025

0.001

C+

146.23 ± 2.04#

0.020

0.020

0.020

0.010

C1

194.98 ± 3.39*

0.667

0.667

0.046

T1

196.57 ± 1.34*

0.040

0.040

T2

174.96 ± 1.57*

0.040

T3

214.31 ± 2.56*

Placental caspase-3 expression following nano-based herbal mahkota dewa treatment. EC: Epithelial Cells, FV: Fetal vessels.

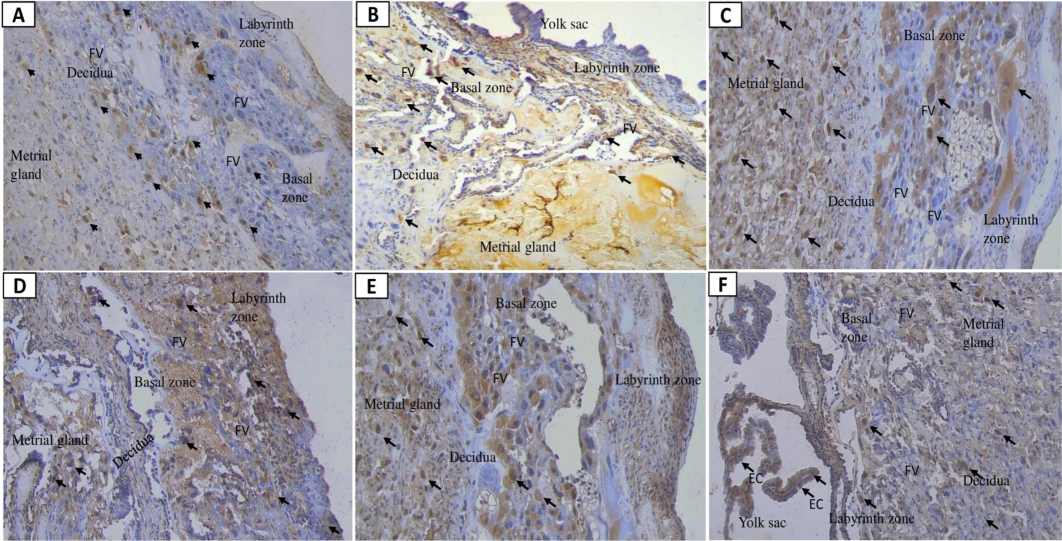

3.3 Expression of caspase-8 on placental

The highest expression of caspase-8 was observed in the positive control group, followed by Nifedipine and Mahkota Dewa (720 mg/kg BW). Prednisone (1.5 mg/kg BW/day) and 6 % NaCl increased caspase levels in the C + groups (Table 2). Mahkota Dewa effectively reduced caspase-8 expression compared to Nifedipine, though levels remained higher than in the negative control (Table 2). Significant differences in caspase-8 and caspase-6 expression were noted (p < 0.01 and p < 0.05). Notably, 180 and 360 mg/kg BW of Mahkota Dewa significantly decreased caspase-8 compared to Nifedipine. Fig. 3 illustrates caspase-8 expression across increasing doses of Mahkota Dewa (Fig. 3D, E, F), including in the yolk sac at 720 mg/kg BW. All groups exhibited elevated caspase-8, mirroring the high levels of caspase-3 expression. In T2, caspase-8 levels decreased with Mahkota Dewa at 360 mg/kg BW, correlating with reduced caspase-3 levels.

Groups

Mean ± SD

Kruskal-Wallis

p-value (Mann-Whitney)

C-

C+

C1

T1

T2

T3

C-

83.29 ± 1.42

0.00

0.000

0.000

0.000

0.010

0.000

C+

403.10 ± 1.14###

0.040

0.040

0.040

0.020

C1

346.88 ± 2.27*

0.033

0.040

0.040

T1

270.23 ± 3.92**

0.040

0.050

T2

155.25 ± 1.21**

0.010

T3

316.25 ± 2.84*

Placental caspase-8 expression following nano-based herbal mahkota dewa treatment. EC: Epithelial Cells, FV: Fetal vessels.

3.4 Expression of caspase-10 on placental

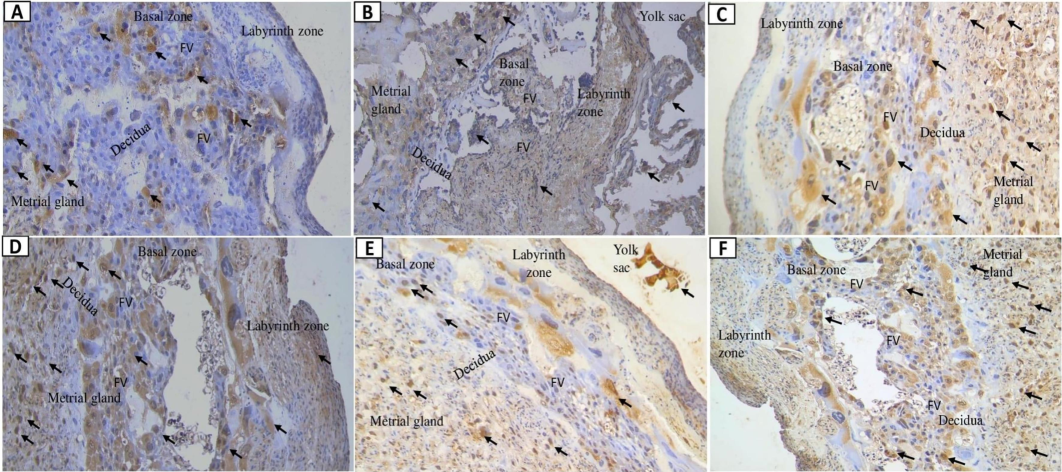

Fig. 4 illustrates caspase-10 expression in the placentas of preeclamptic rats. T3 did not significantly alter caspase-10 levels compared to the C + . However, significant reductions were observed at T1 (p = 0.040) and T2 (p = 0.001). The Kruskal-Wallis test (Table 3) and Mann-Whitney test indicated significant differences between the C + group and those treated with C1, T1, and T2 (p < 0.05). The optimal dose for reducing apoptosis was 360 mg/kg BW, while 720 mg/kg BW appeared to increase apoptosis. Changes in tissue structure are shown in Fig. 4, with caspase-10 present in the labyrinthine area and reduced in the basal zone for both C- (Fig. 4A) and T2 (Fig. 4E) groups. Other groups exhibited high caspase-10 levels in the basal zone. The decidual and metrial glands showed the highest expression of caspase-10, caspase-3, and caspase-8. The T2 group displayed trophoblastic cell apoptosis in the basal zone cavity, with residual staining in the yolk sac, indicating elevated caspase-10 levels. In T2, caspase-3-mediated apoptosis was reduced compared to the positive control and C1 groups.

Placental caspase-10 expression following nano-based herbal mahkota dewa treatment. EC: Epithelial Cells, FV: Fetal vessels.

Groups

Mean ± SD

Kruskal-Wallis

p-value (Mann-Whitney)

C-

C+

C1

T1

T2

T3

C-

74.41 ± 1.35

0.00

0.000

0.040

0.000

0.001

0.000

C+

484 ± 3.04###

0.010

0.040

0.001

0.040

C1

159.07 ± 1.83***

0.040

0.333

0.040

T1

310.67 ± 1.91*

0.040

0.067

T2

188.58 ± 1.30***

0.040

T3

351.86 ± 3.61

4 Discussion

Previous toxicological studies informed the dosage selection of nano-based Mahkota Dewa. Mia et al. (2022) reported that doses up to 500 mg/kg BW were safe for ICR rats, while higher doses (1000–2000 mg/kg BW) resulted in organ toxicity. Simanjuntak & Rumahorbo (2022, 2023) demonstrated that doses between 360–720 mg/kg BW were effective with minimal side effects. Based on this evidence, we selected a dosage range of 180–720 mg/kg BW to ensure both efficacy and safety. In our study, Mahkota Dewa significantly reduced hypertension induced by Prednisone and 6 % NaCl, with notable decreases in blood pressure in the T1, T2, and T3 groups compared to the positive control. This finding supports Rizal et al. (2020), who identified its antihypertensive effects, and Eff et al. (2023), who highlighted its ACE-inhibiting properties. Additionally, Mahkota Dewa decreased MDA levels and enhanced SOD activity, indicating antioxidant effects similar to those of Nifedipine. These results align with Simanjuntak et al. (2019), who attributed these benefits to compounds such as gallic acid, phalerin, and quercetin (Lestari et al., 2023), which mitigate oxidative stress by scavenging free radicals.

Preeclampsia is characterized by imbalances in angiogenic factors, particularly sFlt-1 and VEGF. The C + group exhibited high sFlt-1 and low VEGF levels, indicating dysfunction. Mahkota Dewa (360–720 mg/kg BW) restored this balance, similarly to Nifedipine. However, the 180 mg/kg BW dose effectively reduced sFlt-1 without significantly increasing VEGF, suggesting that higher doses may better restore vascular function. Previous studies suggest that the bioactive compounds in Mahkota Dewa modulate oxidative stress pathways via Nrf2 activation, leading to reduced sFlt-1 production (Christina et al., 2022). Despite lowering oxidative stress, Mahkota Dewa paradoxically increased apoptosis in placental tissue at higher doses, contrasting with cancer studies where it induced apoptosis through caspase pathways (Christina et al., 2022; Kusmardi et al., 2021). In this study, 360 mg/kg BW was optimal for reducing apoptosis, while higher doses exacerbated it, indicating the need for further exploration of its dose-dependent effects in various disease models. Mangiferin, a key compound in Mahkota Dewa, activates the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway and mitigates oxidative stress in preeclampsia (Huang et al., 2020). Other compounds, such as kaempferol and gallic acid, also promote vasorelaxation (Hassan et al., 2020), underscoring its potential for broader applications in cardiovascular and metabolic diseases (Zivković et al., 2024).

This study highlights the potential of nano-based Mahkota Dewa in managing preeclampsia by modulating angiogenic factors and reducing oxidative stress. However, further research is necessary to clarify its effects on placental apoptosis. Its bioactive compounds suggest broader therapeutic applications, laying the groundwork for developing nano-herbal treatments for preeclampsia and other conditions.

5 Conclusion

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that the nano-based herbal formulation of Mahkota Dewa is a promising treatment for preeclampsia. At optimal doses, it effectively lowers blood pressure, reduces oxidative stress, improves the balance of angiogenic factors, and decreases placental apoptosis. These findings warrant further research and development of this formulation as a potential pharmaceutical intervention for preeclampsia.

Ethical approval and informed consent

If the work involves the use of human subjects, the author should ensure that the work described has been carried out in accordance with The Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki) for experiments involving humans. The manuscript should be in line with the Recommendations for the Conduct, Reporting, Editing and Publication of Scholarly Work in Medical Journals and aim for the inclusion of representative human populations (sex, age and ethnicity) as per those recommendations. The terms sex and gender should be used correctly.

All animal experiments should comply with the ARRIVE guidelines and should be carried out in accordance with the U.K. Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act, 1986 and associated guidelines, EU Directive 2010/63/EU for animal experiments, or the National Institutes of Health guide for the care and use of Laboratory animals (NIH Publications No. 8023, revised 1978). The sex of animals must be indicated, and where appropriate, the influence (or association) of sex on the results of the study.

The author should also clearly indicate in the Material and methods section of the manuscript that applicable guidelines, regulations and laws have been followed and required ethical approval has been obtained.

The handling of animals and experimental procedures strictly adhered to the ARRIVE guidelines (Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments) and the EU Directive 2010/63/EU on protecting animals used for scientific purposes. The research protocol was thoroughly evaluated and approved by the Animal Research Ethics Committee at the University of North Sumatra's Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences under the reference number 0921/KEPH-FMIPA/2022, dated February 16, 2023.

Patient consent

Completion of this section is mandatory for Case Reports, Clinical Pictures, and Adverse Drug Reactions. Please sign below to confirm that all necessary consents required by applicable law from any relevant patient, research participant, and/or other individual whose information is included in the article have been obtained in writing. The signed consent form(s) should be retained by the corresponding author and NOT sent to Journal of King Saud University – Science.

Funding source

All sources of funding should also be acknowledged and you should declare any involvement of study sponsors in the study design; collection, analysis and interpretation of data; the writing of the manuscript; the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. If the study sponsors had no such involvement, this should be stated.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Leo Jumadi Simanjuntak: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Cheryl Grace Pratiwi Rumahorbo: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Software, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the University of HKBP Nommensen, Medan, Indonesia.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Prevalence of hypercholesterolemia in Nigeria: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Health. 2020;178:167-178.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Improvement in pharmacological activity of Mahkota dewa (Phaleria macrocarpa (Schef. Boerl)) seed extracts in nanoemulsion dosage form: In vitro and in vivo studies. Pharm. Nanotechnol.. 2023;12(1):90-97.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- P. macrocarpa (Scheff.) Boerl.: An updated review of pharmacological effects, toxicity studies, and separation techniques. Saudi Pharm. J.. 2023;31(6):874-888.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The relationship of knowledge, parity, and anxiety with the event of severe preeclampsia in hospital general of wood area 2021. Sci. Midwifery. 2022;10(2):857-862.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anti-diabetic effects of Phaleria macrocarpa ethanolic fruit extract in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Future J. Pharm. Sci.. 2020;6(1):57.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Preeclampsia: Recent advances in predicting, preventing, and managing the maternal and fetal life-threatening condition. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2023;20(4):2994.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Quantification of the antioxidant activity of plant extracts: Analysis of sensitivity and hierarchization based on the method used. Antioxidants. 2020;9(1):76.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Christina, Y.I., Rifa’I, M., Widodo, N., Djati, M.S.,2022. The combination of Elephantopus scaber and Phaleria macrocarpa leaf extract promotes anticancer activity via the downregulation of ER-α, Nrf2, and PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. J Ayurveda Integr Med 13(4), 100674, 10.1016/j.jaim.2022.100674.

- Evaluation of total phenolic, flavonoid contents, antioxidant, and cytotoxicity activities of various parts of Phaleria macrocarpa (Scheff.) Boerl fruit. IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci.. 2021;743:012026

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Metabolomics combined with chemometric analysis to identify α-glucosidase inhibitors in Phaleria macrocarpa fruit extracts and its molecular docking simulation. S. Afr. J. Bot.. 2024;168:352-359.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors activity is derived from purified compounds such as Fructus P. macrocarpa (Scheff) Boerl. BMC Complement. Med. Ther.. 2023;23(1):56.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Biochemical constituents of Phaleria macrocarpa (Leaf) methanolic extract inhibit ROS production in SH-SY5Y cells model. Biochem. Res. Int. 20202640873

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mangiferin ameliorates placental oxidative stress and activates PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway in mouse model of preeclampsia. Arch. Pharm. Res.. 2020;43(2):233-241.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Karrar SA, Martingano DJ, Hong PL. Preeclampsia. [Updated 2024 Feb 25]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK570611/.

- Potential of Phaleria macrocarpa leaves ethanol extract to upregulate the expression of caspase-3 in mouse distal colon after dextran sodium sulphate induction. Pharmacogn. J.. 2021;13(1)

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lestari, I.C., Lindarto, D., Ilyas, S., Tri, W., Mustofa., Nelva, J., Hasibuan, P., Siahaan, L., 2023. Characterization and Antioxidant Activity of Phaleria macrocarpa (Scheff.) Boerl Leaf Ethanol Extract. IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci 1188, 012046, 10.1088/1755-1315/1188/1/012046.

- Phytochemical characteristics from P. macrocarpa and its inhibitory activity on the peritoneal damage of endometriosis. J. Ayurveda Integr. Med.. 2021;12(2):229-233.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- In vitro, in silico and network pharmacology mechanistic approach to investigate the α-glucosidase inhibitors identified by Q-ToF-LCMS from Phaleria macrocarpa fruit subcritical CO2 extract. Metabolites. 2022;12(12):1267.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Anti-obesity and antihyperlipidemic effects of Phaleria macrocarpa fruit liquid CO2 extract: In vitro, in silico and in vivo approaches. J. King Saud Univ. Sci.. 2023;35(8):102865

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mustapha, N.M.A., Mahmood, N.Z.N., Ali, N.A.M., Haron, N.H., 2017. Khazanah perubatan Melayu: Tumbuhan ubatan jilid 2. Forest Research Institute Malaysia (FRIM), Malaysia.

- Plant phenolics and extracts in animal models of preeclampsia and clinical trials-review of perspectives for novel therapies. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2021;14(3):269.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The effect of P. macrocarpa ethnic food complementary to decrease blood pressure. J. Vocational Nurs.. 2020;1(1):73-79.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Oral chronic toxicity test of nano herbal P. macrocarpa. Pharmacia. 2023;70(2):411-418.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bischofia javanica and P. macrocarpa nano herbal combination on blood and liver-kidney biochemistry in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma-induced rats. Pharmacia. 2024;71:1-8.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Advancing sustainable herbal medicine: Synthesizing nanoparticles from medicinal plants. E3S Web Conf.. 2024;519:03038.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- New ideas for the prevention and treatment of preeclampsia and their molecular inspirations. Int. J. Mol. Sci.. 2023;24(15):12100.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Simanjuntak, L., Siregar, M.F.G., Mose, J., Lumbanraja, S., 2019. The Effects of P. macrocarpa (Scheff.) Boerl Extract on Malondialdehyde (MDA) Level in Preeclampsia-Induced Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cell (HUVEC) Culture. Act. Scie. Medic. 3, 57-61, 10.31080/ASMS.2019.03.0346.

- Acute toxicity test nano-based herbal Mahkota dewa fruit (P. macrocarpa) Pharmacia. 2022;69(4):1063-1074.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Physiological effects of turmeric (Curcuma Longa L) in the form of nano and crude extract. Rasayan J. Chem.. 2023;16(3):1584-1590.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effectiveness of nano-herbal Phaleria macrocarpa on physiological evaluation in Rattus norvegicus. Pharmacia. 2024;71:1-8.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Histological changes in placental rat apoptosis via FasL and cytochrome c by the nano-herbal Zanthoxylum acanthopodium. Saudi J. Biol. Sci.. 2021;28(5):3060-3068.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The effect of the Mahkota dewa (Phaleria macrocarpa) on the density of collagen incision wounds. J. Phys. Conf. Ser.. 2021;1899(1):012071

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Zivković, J., Kumar, K.A., Rushendran, Ilango, K., Fahmy, N.M., El-Nashar, H.A.S., El-Shazly, M., Ezzat, S.M., Lalanne, G.M., Montero, A.R., Peña-Corona, S.I., Gomez, G.L., Sharifi-Rad, J., Calina, D., 2024. Pharmacological properties of mangiferin: bioavailability, mechanisms of action and clinical perspectives. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch Pharmacol 397, 763–781, 10.1007/s00210-023-02682-4.

Appendix A

Supplementary material

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2024.103534.

Appendix A

Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article: