Translate this page into:

Multilocus sequence typing and ERIC-PCR fingerprinting of virulent clinical isolates of uropathogenic multidrug resistant Escherichia coli

⁎Corresponding author. amutha1994santhanam@gmail.com (Amutha Santhanam)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Abstract

Background

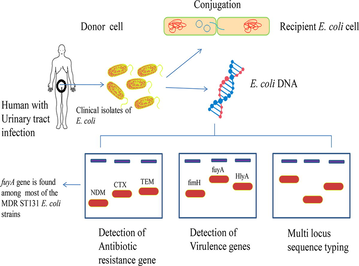

Uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC) is being the most prevalent agent of causing infection in the urinary system of a human being thus takes place by nosocomial and community level spread. An alarming increase in drug resistance on UPEC isolates over the decade is being a serious concern of public health. To address that in this study we have screened the group of UPEC isolates for the presence of various antibiotic resistance genes, virulence-associated genes, and also carried out molecular sequence typing, conjugation assay to type the UPEC strains and evaluate horizontal gene transfer.

Methods

Here, Multilocus sequence typing and identification of O25b-ST131 isolates based on allele-specific PCR method was applied to screen the virulence profile of UPEC.

Result

As a result, we have found that the ESBL, AmpC, NDM, sul, qnr genes, various virulence genes such as fimH, afa, kpsMT KII, kpsMT K1, kpsMT K5, fyuA, iroN, ireA, iutA, hlyA, cnf1 which involve in following respective mechanisms of adherence, capsule synthesis, iron uptake system, toxins on different UPEC isolates. In addition to that, we investigated the horizontal gene transferability of those selective isolates and the respective sequence types of all isolates.

Conclusion

To conclude that the abundant level of fyuA (87%) the yersiniabactin receptor coding gene among the virulence genes, on most of the MDR isolates majorly ST131 suggests that it could become the possible target of anti-virulence to combat multidrug resistance effectively in the future.

Keywords

Uropathogenic E. coli

Urinary tract infection

Multilocus sequence typing

Antibiotic resistance genes

Virulence genes

Horizontal gene transfer

1 Introduction

Urinary tract infection (UTI) affects humans worldwide, which is one of the major bacterial infections caused by Uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC) (Abraham et al., 2012). This infection has been disseminated by the community and nosocomial level and in particular, UPEC accounts for 70–95% of UTIs (Ballesteros-Monrreal et al., 2020). When the E. coli adheres to the urothelium of the urethra the initiation of infection has been started, and its subsequent migration to the bladder and kidney makes inflammation on the host lead to cystitis and pyelonephritis (Ballesteros-Monrreal et al., 2020). The potential of UPEC establishing the infection in the urinary tract depends on the presence of virulence factors. To make successful colonization and survival in the urinary tract, E. coli employs an array of virulence factors such as genes involved in adherence, Iron acquisition/transport system, flagella, and toxins (Bien et al., 2012). These virulence factors protect the bacterium against the flow of urination. Pathogenicity associated island carries these numerous genes and is transferred frequently between the strains horizontally. Various virulence genes such as fimH, a type 1 pilus related gene, a fimbrial adhesion gene-afa, genes fyuA, ireA, iutA, ironN involved in the iron uptake system, Capsule kpsMTII, K1, K5 gene involves in protecting from complement-mediated and phagocytosis killing effect of the host (Lüthje and Brauner, 2014). Toxins like α-hemolysin, the hlyA gene encodes the extracellular lipoprotein, and cnf1, cytotoxic necrotising factor has been reported in the pathogenesis of UTI (Dale and Woodford, 2015). In this study, the isolated UPEC strains from the community showed different types of virulence-associated gene patterns and revealed their association with the patient’s demography, phylogenetic group of each UPEC strain, and the correlation between virulence factor abundance with antibiotic resistance was established.

2 Methodology

2.1 Bacterial strains

A total of 34 non-repetitive E. coli strains isolated from the urine sample of patients with UTI, characterized by conventional biochemical and molecular methods in our previous study (Marialouis and Santhanam, 2016) were used for the present analysis. Ethical clearance was obtained from the institutional ethical committee, Madurai Kamaraj University, Madurai-625021, Tamil Nadu, India. E. coli J53 (AziR) was kindly provided by George A. Jacoby, Lahey Hospital & Medical Center, Burlington, USA. All the strains were maintained in LB agar plates at 4 °C and in LB broth with 30% glycerol at −80 °C. E.coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani broth (HiMedia, India) at 37 °C overnight in shaking at 200 rpm.

2.2 Preparation of template DNA and list of primers for PCR analysis

The boiling lysis method was used to prepare template DNA for PCR (Applied Biosystems Veriti® 96-Well Thermal Cycler, USA). In brief, bacterial cultures (3 mL) were pelleted at 10,000×g for 5 min; the supernatant was discarded and the cell pellet was washed and resuspended in 0.2 mL of sterile MilliQ water. The pellet suspension was then incubated in a boiling water bath at 100 °C for 5 min. After the incubation, the suspension was again precipitated in 10000×g for 5 min. The cell debris was discarded and the DNA containing supernatant was used as a source of template for PCR. The list of primers used in this study are given in Table 1.

S. No

Gene

Primer

Sequence

Length

Annealing

1.

adk

adkF1

5′-TCATCATCTGCACTTTCCGC-3′

583 bp

54 °C

2.

adkR1

5′-CCAGATCAGCGCGAACTTCA-3′

3.

fumC

FumCF

5′-TCACAGGTCGCCAGCGCTTC-3′

806 bp

54 °C

4.

fumCR1

5′-TCCCGGCAGATAAGCTGTGG-3′

5.

gyrB

GyrBF

5′-TCGGCGACACGGATGACGGC-3′

911 bp

60 °C

6.

gyrBR1

5′-GTCCATGTAGGCGTTCAGGG-3′

7.

icd

IcdF

5′-ATGGAAAGTAAAGTAGTTGTTCCGGCACA-3′

878 bp

54 °C

8.

IcdR

5′-GGACGCAGCAGGATCTGTT-3′

9.

mdh

mdhF1

5′-AGCGCGTTCTGTTCAAATGC-3′

932 bp

60 °C

10.

mdhR1

5′-CAGGTTCAGAACTCTCTCTGT-3′

11.

purA

purAF1

5′-TCGGTAACGGTGTTGTGCTG-3′

816 bp

54 °C

12.

PurAR

5′-CATACGGTAAGCCACGCAGA-3′

13.

recA

recAF1

5′-ACCTTTGTAGCTGTACCACG-3′

780 bp

58 °C

14.

recAR1

5′-AGCGTGAAGGTAAAACCTGTG-3′

MLSTO25b-ST131

15.

trpA

trpA.F

5′-GCTACGAATCTCTGTTTGCC-3′

427 bp

65 °C

16.

trpA2.R

5′-GCAACGCGGCCTGGCGGAAG-3′

17.

O25pabB

O25pabBspe.F

5′-TCCAGCAGGTGCTGGATCGT-3′

347 bp

65 °C

18.

O25pabBspe.R

5′-GCGAAATTTTTCGCCGTACTGT-3′

Antibiotic Resistance Genes

19.

blaTEM

TEM-F

5′-TCGGGGAAATGTGCGCG-3′

973 bp

57 °C

20.

TEM-R

5′-TGCTTAATCAGTGAGGACCC-3′

21.

blaCTX-M15

CTXM15-SF

5′-CACACGTGGAATTTAGGGACT-3′

996 bp

56 °C

22.

CTXM15-SR

5′-GCCGTCTAAGGCGATAAACA-3′

23.

blaNDM

blaNDM F

5′-GGTTTGGCGATCTGGTTTTC-3′

621 bp

52 °C

24.

blaNDM R

5′-CGGAATGGCTCATCACGATC-3′

25.

qnrA

QnrAm-F

5′-AGAGGATTTCTCACGCCAGG-3′

580 bp

54 °C

26.

QnrAm-R

5′-TGCCAGGCACAGATCTTGAC-3′

27.

qnrB

QnrBm-F

5′-GGMATHGAAATTCGCCACTG-3′

264 bp

54 °C

28.

QnrBm-R

5′-TTTGCYGYYCGCCAGTCGAA-3′

29.

qnrS

QnrSm-F

5′-GCAAGTTCATTGAACAGGGT-3′

428 bp

54 °C

30.

QnrSm-R

5′-TCTAAACCGTCGAGTTCGGCG-3′

31.

aac(6′)-lb

Aac-F

5′-ATGACTGAGCATGACCTTGC-3′

519 bp

60 °C

32.

Aac-R

5′-TTAGGCATCACTGCGTGTTC-3′

33.

sul1

Sul1-F

5′-CGGCGTGGGCTACCTGAACG-3′

433 bp

69 °C

34.

Sul1-R

5′-GCCGATCGCGTGAAGTTCCG-3′

35.

sul2

Sul2-F

5′-GCGCTCAAGGCAGATGGCATT-3′

293 bp

69 °C

36.

Sul2-R

5′-GCGTTTGATACCGGCACCCGT-3′

37.

MOX-1, MOX-2, CMY-1 & CMY-8 to CMY-11

MOXMF

5′-GCTGCTCAAGGAGCACAGGAT-3′

520 bp

64 °C

38.

MOXMR

5′-CACATTGACATAGGTGTGGTGC-3′

39.

LAT-1 to LAT-4, CMY-2 to CMY-7 & BIL-1

CITMF

5′-TGGCCAGAACTGACAGGCAAA-3′

462 bp

64 °C

40.

CITMR

5′-TTTCTCCTGAACGTGGCTGGC-3′

41.

DHA-1 & DHA-2

DHAMF

5′-AACTTTCACAGGTGTGCTGGGT-3′

405 bp

64 °C

42.

DHAMR

5′-CCGTACGCATACTGGCTTTGC-3′

43.

ACC

ACCMF

5′-AACAGCCTCAGCAGCCGGTTA-3′

346 bp

64 °C

44.

ACCMR

5′-TTCGCCGCAATCATCCCTAGC-3′

45.

MIR-1T & ACT-1

EBCMF

5′-TCGGTAAAGCCGATGTTGCGG-3′

302 bp

64 °C

46.

EBCMR

5′-CTTCCACTGCGGCTGCCAGTT-3′

47.

FOX-1 to FOX-5b

FOXMF

5′-AACATGGGGTATCAGGGAGATG-3′

190 bp

64 °C

48.

FOXMR

5′-CAA AGC GCG TAA CCG GAT TGG-3′

Virulence Genes

49.

FimH

FimH f

5′-TGCAGAACGGATAAGCCGTGG-3′

508 bp

63 °C

50.

FimH r

5′-GCAGTCACCTGCCCTCCGGTA-3′

51.

afa/draBC

Afa F

5′-GGCAGAGGGCCGGCAACAGGC-3′

559 bp

63 °C

52.

Afa R

5′-CCCGTAACGCGCCAGCATCTC-3′

53.

KpsMT II

kpsII f

5′-GCGCATTTGCTGATACTGTTG-3′

272 bp

63 °C

54.

kpsII R

5′-CATCCAGACGATAAGCATGAGCA-3′

55.

KpsMT K1

K1-F

5′-TAGCAAACGTTCTATTGGTGC-3′

153 bp

63 °C

56.

kpsII R

5′-CATCCAGACGATAAGCATGAGCA-3′

57.

KpsMT K5

K5-F

5′-CAGTATCAGCAATCGTTCTGTA-3′

159 bp

63 °C

58.

kpsII R

5′-CATCCAGACGATAAGCATGAGCA-3′

59.

fyuA

FyuA F

5′-TGATTAACCCCGCGACGGGAA-3′

880 bp

63 °C

60.

FyuA R

5′-CGCAGTAGGCACGATGTTGTA-3′

61.

iroN

IroN-F

5′-AAGTCAAAGCAGGGGTTGCCCG-3′

667 bp

63 °C

62.

IroN-R

5′-GACGCCGACATTAAGACGCAG-3′

63.

ireA

IreA-F

5′-GATGACTCAGCCACGGGTAA-3′

254 bp

63 °C

64.

IreA-R

5′-CCAGGACTCACCTCACGAAT-3′

65.

iutA

AerJ f

5′-GGCTGGACATCATGGGAACTGG-3′

300 bp

63 °C

66.

AerJ r

5′-CGTCGGGAACGGGTAGAATCG-3′

67.

hlyA

Hly F

5′-AACAAGGATAAGCACTGTTCTGGCT-3′

1177 bp

63 °C

68.

Hly R

5′-ACCATATAAGCGGTCATTCCCGTCA-3′

69.

cnf1

Cnf F

5′-AAGATGGAGTTTCCTATGCAGGAG-3′

498 bp

63 °C

70.

Cnf R

5′-CATTCAGAGTCCTGCCCTCATTATT-3′

2.3 Multi locus sequence typing and identification of O25b-ST131 isolates based on allele-specific PCR method

Multi locus sequence typing of UPEC isolates was carried out for 12 ESBL isolates belonging to phylogenetic group B2 (n = 11) and D (n = 1) according to the protocol of Achtman et al. (http://mlst.warwick.ac.uk/mlst/dbs/Ecoli). In brief 7 housekeeping genes (adk, fumC, gyrB, icd, mdh, purA and recA) were PCR amplified and sequenced following the protocol of curator. The sequences were submitted to the MLST website to analyze and assign the corresponding allelic profile and based on that STs were assigned.

O25b-ST131 allele-specific PCR was used to screen the non-ESBL isolates for ST131 isolates by the detection of pabB allele-specific to O25b-ST131 strains (Clermont et al., 2009) The PCR amplification was carried out for 25 μl reaction mixture containing 2.5 μl of 10X buffer supplied with Taq DNA polymerase, 20 pmol of each pabB primers (O25pabBspe.F and O25pabBspe.R) and 12 pmol of each trpA primers (trpA.F and trpA2.R), 2 μM of each dNTP and 1U of Taq DNA polymerase. 3 μl of boiled lysate was used as a source of genomic DNA. The PCR amplification was performed with initial denaturation for 4 min at 94 °C; 30 cycles of denaturation for 5 s at 94 °C, annealing 10 s at 65 °C, and extension 10 s at 72 °C; and final extension of 5 min at 72 °C in the thermal cycler. The resultant amplified product was analyzed by electrophoresis in a 1.2% (w/v) agarose gel.

2.4 PCR based detection of antibiotic resistance genes

Antibiotic-resistant genes such as β-lactamases (blaTEM and blaCTX M-15) blaAmp-C, blaNDM), quinolones (qnrA, qnrB, qnrS, and aac(6′)-lb-cr) and sulphonamides (sul1 and sul2), were amplified by PCR using specific primers as described previously (Muzaheed et al., 2008; Poirel et al., 2011).

2.5 Amplification of virulence genes from UPEC strains by multiplex PCR

All E.coli isolates were screened for the genetic determinants that encode, adhesions (type I fimbriae [fimH], a fimbrial adhesion [afa]), protectins (kpsMT [kII, k1, k5-antigen], iron-acquisition systems (fyuA, iroN, ireA, Aerobactin [aerJ]), and toxins Hemolysin [hly], the cytotoxic necrotizing factor I [cnfI] and the 11 targeted genes and their primer sequences (Table 1) were chosen (Johnson and Stell, 2000). The targeted 11 gene primers were divided into three sets of multiplex reaction mixtures as follows: Multiplex1 (fimH, afa, kpsMTkII, k1, k5), Multiplex2 (fyuA, iroN, ireA, aerJ), Multiplex 3 (hly, cnfI). A volume of 25 µl of each multiplex polymerase chain reaction consists of 200 µM deoxynucleotide triphosphates (dNTPs), 2.5 µl of 10X PCR buffer, 1 µl of 1 µM forward primer, 1 µl of 1 µM reverse primer of each gene, 3 µl of DNA, 0.6 units of Taq DNA polymerase and 16.8 µl sterile MillQ water. The resulted PCR products were run on 1.5% (w/v) agarose gel.

2.6 Conjugation assay

Conjugal transfer of antibiotic resistance-conferring plasmid carried by UPEC isolates to E. coli J53 (AziR) recipient strain was accomplished by broth mating assay (Jacoby and Han, 1996). The resulting transconjugants were confirmed by culturing on LB agar plates containing sodium azide (100 mg/ml) and ceftazidime (30 mg/ml) by the double selection method. To establish the discrete difference between the wild UPEC isolates and transconjugants, RAPD analysis was performed to have a distinct pattern on the phylogeny (Abraham et al., 2012).

2.7 Molecular typing of UPEC isolates with ERIC-PCR fingerprinting:

Repetitive sequence-based polymerase chain reaction (Rep-PCR) was performed using specific ERIC primers (Versalovic et al., 1994). In brief, the amplification was performed with initial denaturation for 5 min at 94 °C; 30 cycles of denaturation for 30 sec at 94 °C, annealing 30 s at 55 °C and extension 30 s at 72 °C; and final extension of 7 min at 72 °C in thermal cycler. The resultant amplified product was analyzed by electrophoresis in 1.2% (w/v) agarose gel. The images were analyzed and the dendrogram was constructed with PyElph 1.4 software is based on the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean (UPGMA) analysis (Pavel and Vasile, 2012).

2.8 Data analysis

The Pearson co-efficient statistics were used to analyze the association of virulence genes pattern with the corresponding phylogenetic group of all E.coli isolates. The patient’s clinical manifestations and demography were compared with the studied virulence gene pattern by descriptive statistics.

3 Results

3.1 Multilocus sequence typing and O25b allele-specific identification of ST131 among UPEC isolates

Totally 21 different alleles were identified which were assigned into 3 different sequence types (ST) by MLST analysis of 12 ESBL isolates with ST131 (B2) dominated (n = 10) followed by ST127 (B2) and ST405 (D) with each one (Table 2). 7 non-ESBL isolates (B2) were identified as O25b-ST131 based on O25pabB based allele-specific PCR. Along with 10 ESBL isolates, a total number of 17 O25b-ST131 isolates were present.

Culture No.

Sequence Type

Virulence Genes

Afa/draBc (559 bp)

FimH (508 bp)

KPSMT II (272 bp)

KPSMTK5 (159 bp)

KPSMTK1 (153 bp)

FyuA (880 bp)

Iron N (667 bp)

IutA (300 bp)

IreA (254 bp)

HlyA (1177 bp)

Cnf1 (498 bp)

XA01

ST131

+

+

+

–

–

+

–

+

–

+

+

XA03

–

+

–

–

–

+

–

+

–

–

–

XA04

ST131

–

+

+

+

+

+

–

+

+

–

–

XA06

ST131

–

+

+

+

+

+

–

+

–

+

–

XA08

ST405

–

+

+

+

–

+

–

–

–

–

–

XA09

ST127

–

+

–

–

–

+

+

–

–

+

+

XA10

ST131

–

+

+

+

+

+

–

+

–

+

–

XA13

ST131

–

+

+

+

–

+

–

+

–

+

–

XA19

+

–

–

–

–

+

–

+

–

–

–

XA20

–

+

+

+

+

+

+

–

–

–

+

XA21

ST131

+

+

+

–

–

+

–

+

–

+

+

XA26

ST131

–

+

+

–

+

+

–

+

–

–

–

XA27

ST131

–

+

+

+

–

+

–

+

–

–

–

XA28

–

+

+

+

+

+

+

–

+

+

–

XA31

ST101

+

–

–

–

+

–

+

–

–

–

XA32

+

+

+

–

–

+

–

+

–

+

+

XA37

ST131

–

+

+

–

–

+

–

+

–

–

–

XA39

–

+

+

+

+

+

+

–

–

–

+

XA42

ST131

–

+

+

–

–

+

–

+

–

+

+

XA43

ST131

–

+

+

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

XA45

ST131

–

+

+

+

+

+

–

+

–

+

+

XA50

–

+

–

–

–

–

+

–

–

–

+

XA51

–

+

–

–

–

–

+

–

–

–

+

XA55

ST131

–

+

+

–

+

+

–

+

–

+

–

3.2 Identification of antibiotic resistance genes among UPEC isolates

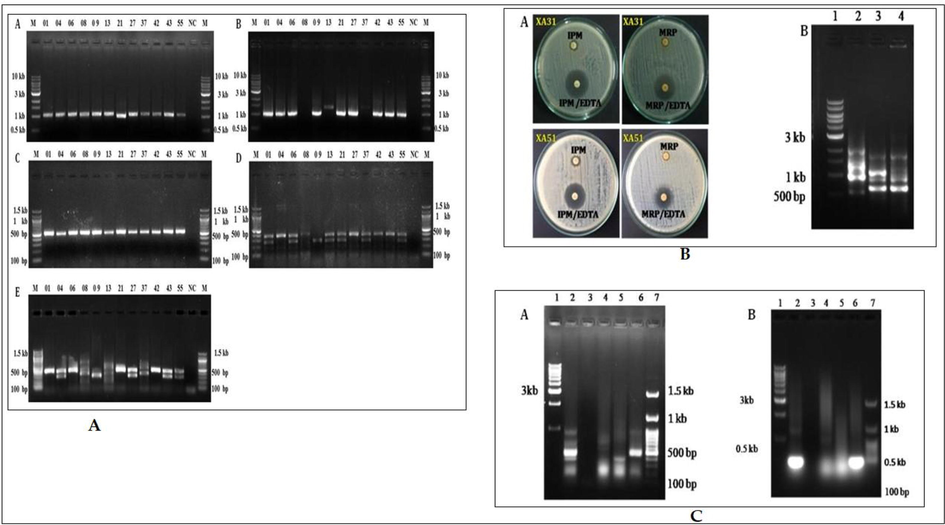

Various antibiotic-resistant genes were identified by different PCR methods. Among them blaTEM was dominant (n = 14), followed by blaCTX-M-15 (n = 11) of β-lactamase genes (Fig. 1a). Metalo β-lactamase gene blaNDM was found in two isolates (XA31 and XA51), which belong to phylogenetic group B1 (Fig. 1b). MOXM of AmpC was identified by multiplex PCR in two isolates (XA03 and XA51) (Fig. 1c). Among the fluoroquinolone resistance genes, aac(6′)-Ib-cr was dominant (n = 12), followed by qnrS (n = 11) and qnrB (n = 7), whereas qnrA was not detected in any of the isolates. In seven isolates that contain qnrB, six belong to ST131 and another one, ST 405. All ST131 and ST405 of group D had qnrS, but it was absent in E. coli XA09 of ST127 belongs to B2. Among the sulphonamide resistance genes sul1 was dominant (n = 8) followed by sul2 (n = 6). Four ST131 isolates (XA04, XA27, XA43, and XA55) had both sul1 and sul2. Both XA31 and XA51 were tested positive for blaTEM, blaCTX-M-15, and blaNDM, along with which blaAMPC was also present in XA51. Even though XA31 was phenotypically identified as an AmpC variant, no specific genes were detected by PCR based method (Fig. 1c).

(A-C): A). PCR amplification of drug resistant genes. (A) blaTEM (972 bp); (B) blaCTX-M-15 (996 bp); (C) aac(6′)-Ib-cr (580 bp); (D) qnrA (580 bp), qnrB (264 bp) and qnrS (428 bp) genes; (E) sul1 (433 bp) and sul2 (293 bp) genes. Lane M- 1 kb DNA ladder, NC-Negative control and lane numbers represents the corresponding UPEC isolates such as 01 for E. coli XA01 and 55 for E. coli XA55 respectively: B). (A) Double disc synergy test for the phenotypic detection of beta-lactamase NDM: IPM (Imipenem)/EDTA, MRP (Meropenem)/EDTA. (B) PCR-based detection of β lactamase genes (A) TEM, CTX (B) AmpC, (C) NDM in culture lysate; C), (A) PCR-based detection of β lactamase gene, blaAmpC, in culture lysate. (B) PCR amplification of MOXM type AmpC beta-lactamase gene by UPEC strains. Lane 1: 1 kb ladder, Lane 2: XA03, Lane 3: XA05, Lane 4: XA08, Lane 5: XA31, Lane 6: XA51 and Lane 7: 100 bp ladder.

3.3 Analysis of the virulence profile of UPEC isolates

The studied virulence genes, their frequencies among the clinical strains are presented in Table 2. The prevalence of 11 virulence genes among UPEC strains were as follows, fimH (n = 23), Afa (n = 4), kpsMTII (n = 18), kpsMTK5 (n = 10), kpsMTK1 (n = 9), FyuA (n = 21), iroN (n = 6), iutA (n = 16), IreA (n = 2), hlyA (n = 11) and cnf1 (n = 10). The results are shown in Fig. 2a and b. Among the virulence genes, fimH responsible for adhesion was highly prevalent in most of the strains. Anyone of all 11 virulence genes was at least found in all clinical strains. The three virulence genes such as fimH, kpsMTII, FyuA from different pathogenic mechanisms were detected majorly in UPEC strains. ireA was the least one found on only two isolates. Among the genes related to the iron acquisition system FyuA, iutA were more common than iroN, ireA. The abundance of toxin genes cnf 1, hlyA was almost equal to the respective strains. Arrangement of various virulence genes on different combinations makes the distinct type of gene patterns, a total of 18 types of virulence patterns were identified on 24 strains. Of which afa/fimH/kpsMTKII/fyuA/iutA/hlyA/cnf1 pattern as 12.5% and following four different patterns such as fimH/kpsMTII/kpsMTK5/kpsMTK1/fyuA/iutA/hlyA, fimH/kpsMTII/kpsMTK5/kpsMTK1/fyuA/iroN/cnf1, fimH/kpsMTII/fyuA/iutA, fimH/iroN/cnf1 as 8.3% each was found among the UPEC isolates. In total 14 (58%) isolates were found to be carrying more numbers 6 to 8 of virulence genes.

(A-C): A) Detection of virulence genes in UPEC profile strains XA03, XA04, XA06, and XA08. Lane 1 1 Kb ladder, 2 Gene pool 1 XA03, 3–1 XA04, 4–1 XA06, 5–1 XA08, 6 Gene pool 2 XA03, 7–2 XA04, 8–2 XA06, 9–2 XA08, Lane 10 Gene pool 3 XA03, 11–3 XA04, 12–3 XA06, 13–3 XA08, 14 100 bp ladder; B) Dendrogram of virulence gene profile and the corresponding phylogenetic group of all E. coli isolates. C) Distribution of Virulence genes among ST131 and non ST131 UPEC isolates.

3.4 Phylogenetic analysis of virulence gene profile of uropathogenic E. coli

The phylogenetic tree was constructed based on virulence gene profile which clearly showed the relationship between strains and their diversity. The tree consists of two major clusters, which is divided further into several clades. All ST131 isolates were present in Cluster-I. E. coli XA01, E. coli XA21, E. coli XA13 and E. coli XA27 are present in a single node belong to B2-ST131 and ESBL producing isolates. Whereas B2-ST131 isolates E. coli XA06 and E. coli XA10 were grouped together, which differs in their antibiotic resistant pattern, where the earlier one was ESBL. Another B2-ST131 isolates E. coli XA26 and E. coli XA55 were also grouped together in which the later was ESBL producer. Phylogenetic group B1 isolates E. coli XA03 and E. coli XA31 were also grouped together both produce AmpC β-lactamase, where the later was also positive for ESBL and NDM (Fig. 2b). However, ESBL-AmpC-NDM variant E. coli XA51 was grouped in cluster-II separately, which differed from other group B1 isolates E. coli XA31 in their virulence profile.

3.5 Distribution of virulence genes among ST131 and non-ST131 UPEC isolates

The distribution of virulence genes was compared among ST131 (n = 13) isolates and non-ST131 (n = 11) isolates (Fig. 2c). Most of the virulence gene were dominant among ST131 isolates (fimH, kpsMTII, kpsMT5, kpsMT1, fyuA, iutA and hly) when compared with non-ST131 isolates (afa/draBC, iroN, ireA and cnf1). It is significant to note that both fyuA and iutA were detected among all the ST131 isolates, ireA was detected in only one ST131 isolate (E. coliXA04) and ironN was absent in all ST131 isolates. Whereas among the iroN was higher (55%) among non-ST131 isolates, when compared with iutA (28.3%). Among the toxin genes hly was dominant among ST131 isolates (ST131-63.3% vs non-ST131-28.3%) and cnf1 was dominant among non-ST131 isolates (ST131-31.7% vs non-ST131-55%). The ESBL producing non-ST131 isolates (n = 6) were found to have less virulence genes, when compared with ST131 and non-ESBL-non-ST131 isolates.

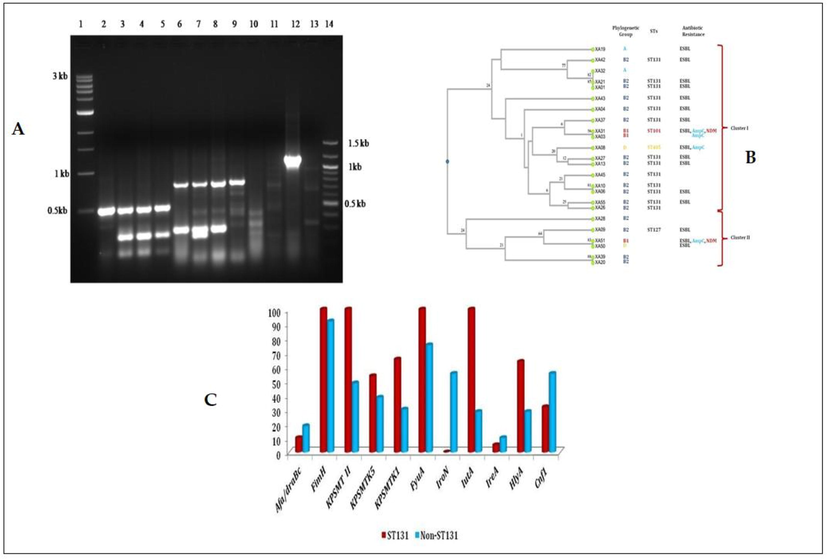

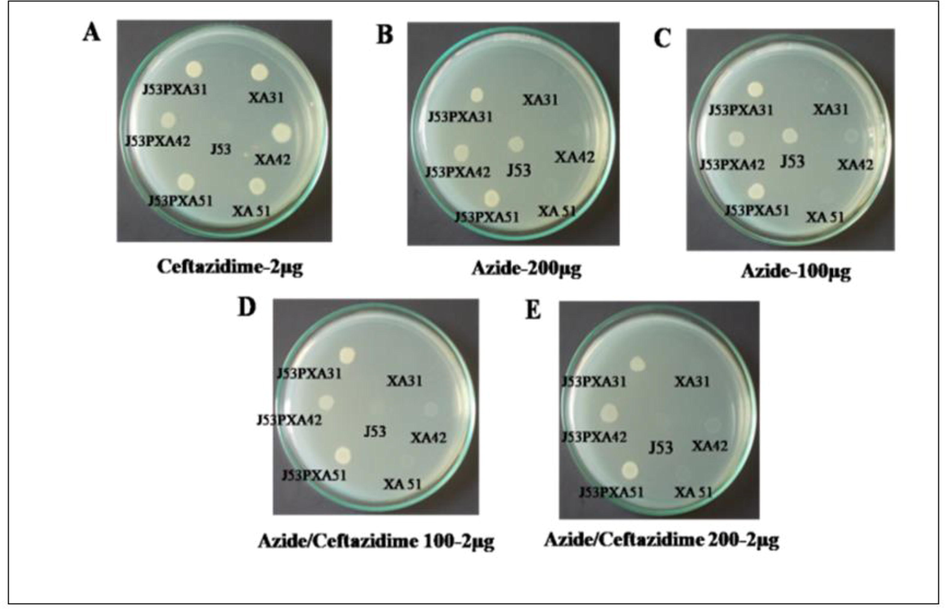

3.6 Analysis of horizontal gene transfer

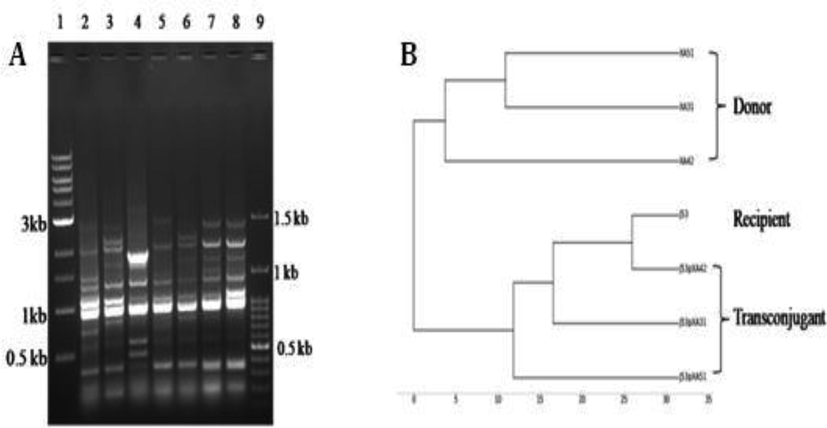

Antibiotic resistance in E. coli frequently occurs through the process of horizontal gene transfer. Conjugation assay was performed to confirm the transferable drug-resistant plasmids present among the UPEC isolates using E. coli J53 as recipient strain by liquid matting experiment. As a result, in ceftazidime (100 µg) containing LB medium, both the E. coli transconjugants (J53pXA04, J53pXA09, J53pXA21, J53pXA31, J53pXA42, and J53pXA51) and E. coli wild isolates (XA31, XA42, and XA51) were grown except the E. coli J53 strain. In the case of azide (100 µg) containing medium both the transconjugants and J53 recipient strain were grown except the wild strain. Finally, both of the antibiotics were used as double selection to know the transfer of resistance genes between the strains. It was found that the transconjugants only were grown and none of the others (Fig. 3). And to distinguish transconjugants among other RAPD analyses was done, this showed that, there was a difference in the RAPD banding pattern of transconjugants and wild strains (Fig. 4). Transconjugants were obtained from 6 isolates (XA04, XA09, XA21, XA31, XA42, and XA51) by conjugation assay, which possessed transferable plasmids. The conjugation was confirmed genotypically by RAPD analysis among 3 isolates (XA31, XA42, and XA51) and phenotypically among the remaining isolates (XA04, XA09, and XA21). The disc diffusion assay confirmed the transfer of resistant markers. Along with cephalosporin resistance, resistances to other classes were also found such as fluoroquinolone, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and tetracycline among 2 isolates (XA04 and XA09). Conjugal transfer of NDM resistance was confirmed among 2 isolates (XA31 and XA51).

(A-E): Characterization of NDM gene dissemination through horizontal gene transfer by conjugation with E. coli J53. A) Transconjucants J53PXA31, J53PXA42, J53PXA51, wild XA31, XA42, XA51 in ceftazidime-2 µg; B) Transconjucants J53PXA31, J53PXA42, J53PXA51, wild XA31, XA42, XA51 in azide-200 µg; C) Transconjucants J53PXA31, J53PXA42, J53PXA51, wild XA31, XA42, XA51 in azide-100 µg; D) Transconjucants J53PXA31, J53PXA42, J53PXA51, wild XA31, XA42, XA51 in azide/ceftazidime 100 µg. E) Transconjucants J53PXA31, J53PXA42, J53PXA51, wild XA31, XA42, XA51 in azide-200 µg.

(A-B) A) RAPD profile of donor and transconjugants Lane 1: 1 kb ladder, Lane 2: XA31, Lane 3: XA51, Lane 4: XA42, Lane 5: J53pXA31, Lane 6: J53pXA51, Lane 7: J53pXA42, Lane 8: XAJ53, Lane 9: 100 bp ladder; B) Dendrogram of RAPD profile.

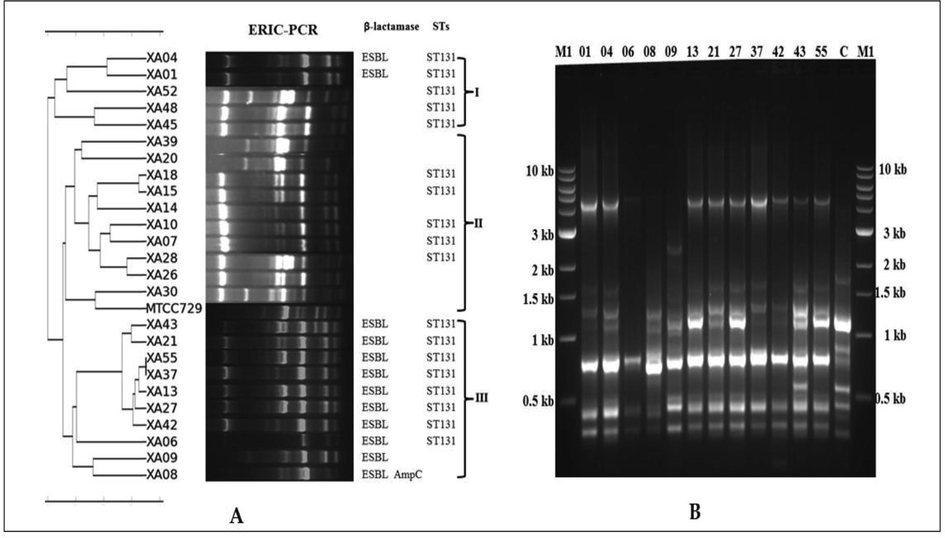

3.7 ERIC-PCR fingerprinting of O25b-ST131 isolates

To analyze the genetic diversity of O25b-ST131 isolates belonging to phylogenetic group B2 ERIC-PCR was carried out. The genetic variation among the UPEC isolates with different banding patterns, which ranged from nearly 300 bp to 4.5 kb, was revealed by the results of ERIC-PCR analysis (Fig. 5a and b).

(A-B): A) Dendrogram of ERIC-PCR profiles based on Unweighted Pair Group Mathematical Average (UPGMA) clustering algorithm; B) The results of ERIC-PCR amplified products of phylogenetic group B2 isolates. M1- 1 kb ladder, M2-100 bp ladder, C- E. coli MTCC729 and all other numbers represented their corresponding UPEC isolates such as 01 for E. coli XA01 and 04 for E. coli XA04 respectively.

Another genetic similarity on O25b-ST131 was also revealed by ERIC-PCR profile-based dendrogram by placing them into three different clusters (I to III). Five UPEC isolates among which two isolates were (E. coli XA01 and E. coli XA04) ESBL which belongs to ST-131 were placed to cluster I. In cluster II, on eleven non ESBL isolates five ST-131 isolates were grouped along with six non-ST-131 isolates. Whereas in cluster III eight ST 131 isolates were with E. coli XA09 (ST127) and E. coli XA08 (ST405).

4 Discussion

Community spreading of multidrug-resistant E. coli isolates is a global threat in concern. When multiple virulence factors of UTIs were added along with MDR, it became complicated in therapeutics of UPEC isolates (Paniagua-Contreras et al., 2018; Raeispour and Ranjbar, 2018). Molecular tools have been used widely to analyze the clonal population of UPEC isolates causing community-acquired UTIs worldwide (Vejborg et al., 2011). In the present study, MLST was used along with ERIC-PCR fingerprinting to understand the genetic diversity of UPEC isolates spreading in the region of the southern part of India. The study revealed the presence of ST131 isolates, which is one of the pandemic strains causing UTIs. There were several reports of CTX-M-15 as selective markers along with fluoroquinolone and trimethoprim/sulphamethoxazole in the spreading of ST131 isolates (Decano, et al., 2020). The presence of multiple virulence factors makes it much more complicated. Here in this study, 34 strains were subjected to analyze the virulence factors, in a total of 17 isolates were identified as ST131, among which 7 isolates were non-ESBL. The report reveals the community spreading of non-ESBL isolates along with the ESBL among ST131 isolates. In the present study it was found that the virulence genes were more dominant among the UPEC isolates of group B2 followed by groups D, A and B1, which clearly says their role on causing UTI. Contreras-Alvarado et al. (2021) also reported that ST131 (63.63%) was associated initially with phylogenetic group B2. Though non-ESBL ST131 isolates were susceptible to most of the antibiotics, the presence of multiple virulence genes may support their adaptability to cause UTIs and are responsible for their spreading in the community.

The Enterobacteriaceae that produces the blaAmpC β-lactamase has been a major challenge in the health care providers and community as well. The increasing rate of resistance towards the last line drugs particularly cefoxitin is highly alarming nowadays. Our study demonstrates the presence of the blaAmpC β-lactamase gene in the few clinical isolates of UPEC, and only the MOX type of pblaAmpC was found in two isolates, shows that it could be plasmid-mediated and phenotypically presence and genotypically absence of blaAmpC in the rest of the isolates indicates which might be chromosomally mediated. But in other studies which reported the prevalence of blaAmpC are higher. Also in India, it has been reported that some of the studies have all types of pAmpC (CIT, DHA, MOX, ACC, and CMY) with the co-production of β-lactamase (Peirano et al., 2014).

During the evolution of bacterial spread, several important genetic events take place through horizontal gene transfer in the form of conjugation and others. This provides the platform through the plasmid to the different members of Enterobacteriaceae for the transmission of the drug resistance gene against various antibiotics (Pérez-Pérez and Hanson, 2002; Al-Ansari et al., 2021). The spreading of resistance genes by transferable plasmids carrying co-resistance of various antibiotic classes were reported elsewhere (Mukherjee and Mukherjee, 2019). The outcome of the conjugation analysis shows that the withstanding ability of recipient strain E. coli J53 on ceftazidime antibiotic for three subsequent generations indicates stable expression of ESBL genes such as blaCTX-M-15 and blaTEM on the plasmid. Further, it states that the transferring nature of resistance genes from donor to recipient reflects as they are mobile genes born elsewhere, also that could involve in the dissemination of heavy risk genes and it poses threat to public health the way it spreads across the bacterial population (Pitout et al., 1998). Carbapenem antibiotics are being the first choice of treatment for the severe infections caused by the ESBL producing bacteria. However, various findings state that the β-lactam hydrolyzing nature of blaNDM-7 poses a high risk of emergence of resistance globally (Poirel et al., 2011; Terlizzi et al., 2017). In our study, we found that the two isolates have developed resistance to carbapenem and that confers the expression of carbapenemase which was identified as blaNDM-7. Taken together, it is necessary to discover new therapeutic options to overcome the problems faced by the health care sector.

Virulence factors are a crucial determinant of pathogenicity (Najafi et al., 2018). Most of these factors are connected to site-specific infections and largely belong to one of the pathogenic approaches: adhesions, iron acquisition systems, toxins, immune evasion mechanisms, and invasions. The severity of UTIs is associated with the host susceptibility and multiple virulence genes carrying the potential of UPEC (Ballesteros-Monrreal et al., 2020).

As the mounting antibiotic resistance gaining on bacteria against most drugs, it is necessary to improve effective control and disease management and promote alternative therapeutic strategies. It is required that the virulence factors involved in pathogenesis and associating factors should be characterized (Abraham et al., 2012). In UTI development the first step to initiate bacterial colonization on uroepithelial cells is the adherence of E. coli (Lüthje and Brauner, 2014). The adhesion virulence factor genes are more frequently occurring in UPECs. To establish the UTI and subsequent progression to urosepsis, fimbriae play an important role (Queipo-Ortuño et al., 2008).

Most of the strains (96%) in our study carry the fimH gene-fimbrial adhesion of type 1 pili which are similar to other studies and mainly involve adherence to the bladder but also in internalization and further formation of intracellular bacterial communities (Raeispour and Ranjbar, 2018; Ruiz del Castillo et al., 2013). Due to the prevalence of fimH among the UPEC isolates, investigations are underway to target fimH as a vaccine candidate for the prevention of UTI. Afa adhesin (afa gene) was found in 16% of UPEC strains. Afimbrial adhesions (afa), though associated with UTI also involve gestational pyelonephritis and may favor the establishment of chronic and/or recurrent urinary tract infections (Schneider et al., 2011). A capsule made of polysaccharides serves as a virulence factor is located on the surface of bacteria protecting against the host immune system (Steiner et al., 1996; Al-Ansari et al., 2020). Capsule helps bacterium to escape from the host defense such as phagocytosis and complement-mediated effect, K1 and K5 involve in preventing the humoral immunity by doing molecular mimicry to host tissue (Terlizzi et al., 2017).

KPSMTII was found in 75%, K5, and K1 accounts for 41%, and 37% of E. coli isolates causing UTI. α-Hemolysin (Hly-A) and cytotoxic necrotizing factor (cnf1) secreted by the UPEC isolates in high concentrations damages the host cell membrane by pore formation leads to the acquisition of iron and nutrient in bacteria (Steiner et al., 1996). In this study, 46% of UPEC isolates were carried hemolysin (hly) and 41% of cytotoxic necrotizing factor (cnf1) was found in UPEC isolates.

During UTI iron is required for the growth of E. coli, because the bladder is an iron-limiting environment. Thus, UPEC strains deploy genes involved in the iron acquisition process such as fyuA, iroN, iutA, ireA (Vejborg et al., 2011). In our study, 87%, 25%, 66%, 8.3% of UPEC isolates were found to carry as fyuA, iroN, iutA, ireA genes respectively. Among the iron uptake system genes, the high prevalence of fyuA (87%) gene encoding the yersiniabactin receptor involves in the iron-chelating process suggests it could be the best predictor of the efficient colonization of UPEC in the bladder environment of humans (Vejborg et al., 2011; Yun et al., 2014; Shakhatreh et al., 2019).

5 Conclusion

In this study, we have found the multidrug-resistant carrying different uropathogenic E. coli isolates with distinct sequence types particularly the high prevalence of ESBL producing ST131 E. coli the major epidemic group of UPEC. And the number of UPEC isolates included in this study is less sufficient to analyze various parameters extensively, even though we found, some abundant level of genes, particularly the yersiniabactin receptor encoding gene among the various virulence genes analyzed on most of the MDR isolates majorly belong to ST131 lineage suggests that it could become the possible target of anti-virulence to combat multidrug resistance effectively in future. Therefore, allowing further detailed investigation would establish that the virulence genes could also act as effective targets in drug therapy.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Venkatesan Ramakrishnan: Methodology, Visualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft. Xavier Alexander Marialouis: Methodology, Visualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft. Mysoon M. Al-Ansari: Visualization, Writing – review & editing. Latifah Al-Humaid: Formal analysis. Amutha Santhanam: Conceptualization, Supervision. Parthiba Karthikeyan Obulisamy: Software.

Acknowledgement

The DST PURSE –MKU and UGC-MRP (F39-220/2010 SR). The authors extend their appreciation to the Researchers Supporting Project Number (RSP-2021/228), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Molecular characterization of Escherichia coli strains that cause symptomatic and asymptomatic urinary tract infections. J. Clin. Microbiol.. 2012;50(3):1027-1030.

- [Google Scholar]

- Isolation and molecular characterization of multidrug-resistant Salmonella enterica serovars. J. Infect. Public Health. 2021;14(12):1767-1776.

- [Google Scholar]

- Challenging multidrug-resistant urinary tract bacterial isolates via bio-inspired synthesis of silver nanoparticles using the inflorescence extracts of Tridax procumbens. J. King Saud Univ. Sci.. 2020;32(7):3145-3152.

- [Google Scholar]

- Virulence and resistance determinants of uropathogenic Escherichia coli strains isolated from pregnant and non-pregnant women from two states in Mexico. Infect. Drug Resist.. 2020;13:295-310.

- [Google Scholar]

- Role of uropathogenic Escherichia coli virulence factors in development of urinary tract infection and kidney damage. Int. J. Nephrol.. 2012;2012:681473.

- [Google Scholar]

- Rapid detection of the O25b-ST131 clone of Escherichia coli encompassing the CTX-M-15-producing strains. J. Antimicrob. Chemother.. 2009;64(2):274-277.

- [Google Scholar]

- Molecular epidemiology of multidrug-resistant uropathogenic Escherichia coli O25b strains associated with complicated urinary tract infection in children. Microorganisms. 2021;9:2299.

- [Google Scholar]

- Extra-intestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli (ExPEC) Disease, carriage and clones. J. Infect.. 2015;71(6):615-626.

- [Google Scholar]

- Decano, A. G, et al., 2020. Plasmids shape the diverse accessory resistomes of Escherichia coli ST131. Access Microbiol. 3(1): acmi 000179.

- Extended virulence genotypes of Escherichia coli strains from patients with urosepsis in relation to phylogeny and host compromise. J. Infect. Dis.. 2000;181(1):261-272.

- [Google Scholar]

- Virulence factors of uropathogenic E. coli and their interaction with the host. Adv. Microb. Physiol.. 2014;65:337-372.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antibiotic resistance, RAPD- PCR typing of multiple drug resistant strains of Escherichia Coli from urinary tract infection (UTI) J. Clin. Diagn. Res.. 2016;10(3):Dc05-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Characterization and bio-typing of multidrug resistance plasmids from uropathogenic Escherichia coli isolated from clinical setting. Front. Microbiol.. 2019;10:2913.

- [Google Scholar]

- High prevalence of CTX-M-15-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae among inpatients and outpatients with urinary tract infection in Southern India. J. Antimicrob. Chemother.. 2008;61(6):1393-1394.

- [Google Scholar]

- Distribution of pathogenicity island markers and virulence factors in new phylogenetic groups of uropathogenic Escherichia coli isolates. Folia Microbiol.. 2018;63(3):335-343.

- [Google Scholar]

- Multiple antibiotic resistances and virulence markers of uropathogenic Escherichia coli from Mexico. Pathog. Glob. Health. 2018;112(8):415-420.

- [Google Scholar]

- PyElph: a software tool for gel images analysis and phylogenetics. BMC Bioinf.. 2012;13:9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Characteristics of Escherichia coli sequence type 131 isolates that produce extended-spectrum β-lactamases global distribution of the H30-Rx sublineage. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.. 2014;58(7):3762-3767.

- [Google Scholar]

- Detection of plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamase genes in clinical isolates by using multiplex PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol.. 2002;40(6):2153-2162.

- [Google Scholar]

- beta-Lactamases responsible for resistance to expanded-spectrum cephalosporins in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Escherichia coli and Proteus mirabilis isolates recovered in South Africa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.. 1998;42(6):1350-1354.

- [Google Scholar]

- Multiplex PCR for detection of acquired carbapenemase genes. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect Dis.. 2011;70(1):119-123.

- [Google Scholar]

- Preparation of bacterial DNA template by boiling and effect of immunoglobulin G as an inhibitor in real-time PCR for serum samples from patients with Brucellosis. Clin. Vacc. Immunol.. 2008;15(2):293-296.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antibiotic resistance, virulence factors and genotyping of Uropathogenic Escherichia coli strains. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 2018;7:118.

- [Google Scholar]

- Molecular characterization of multiresistant Escherichia coli producing or not extended spectrum β-lactamases. BMC Microbiol.. 2013;13(1):84.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mobilisation and remobilisation of a large archetypal pathogenicity island of uropathogenic Escherichia coli in vitro support the role of conjugation for horizontal transfer of genomic islands. BMC Microbiol.. 2011;11:210.

- [Google Scholar]

- Uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC) in Jordan: Prevalence of urovirulence genes and antibiotic resistance. J. King Saud Univ. Sci.. 2019;31(4):648-652.

- [Google Scholar]

- Steiner, K., Abigail, Salyers, A., Dixie D. Whitt, 1996. Bacterial Pathogenesis. A Molecular Approach, XXVII + 418 S., 137 Abb., 22 Tab. Washington D.C. 1994.ASM Press. L 24.95. ISBN: 1-55581-094-2. J. Basic Microbiol. 36(2): p. 148-148.

- UroPathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC) Infections Virulence Factors Bladder Responses Antibiotic and Non-antibiotic Antimicrobial Strategies. Front. Microbiol.. 2017;8

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Comparative genomics of Escherichia coli strains causing urinary tract infections. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.. 2011;77(10):3268-3278.

- [Google Scholar]

- Genomic fingerprinting of bacteria using repetitive sequence-based polymerase chain reaction. Methods Mol. Cell. Biol.. 1994;11:5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Virulence factors of uropathogenic Escherichia coli of urinary tract infections and asymptomatic bacteriuria in children. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect.. 2014;47(6):455-461.

- [Google Scholar]