Translate this page into:

MALDI-TOF MS-based identification and antibiotics profiling of Salmonella species isolated from retail chilled chicken in Saudi Arabia

⁎Corresponding author. rhindi@kau.edu.sa (Rashad R. Al-Hindi)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Objectives

Salmonella is a well-known foodborne pathogen that is spread around the world. It causes diseases both in animals and humans. The development of antibiotic-resistant Salmonella strains results in the failure of formerly effective drugs in humans and animals and poses a serious threat to world health. In the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, the rise in Salmonella prevalence in poultry is seen as a serious problem. Saudi Arabia has endured several epidemics of Salmonella infections with varied patterns of drug resistance in the last few decades.

Methods

A total of 112 chilled chicken carcass of five different local poultry companies were procured from retail outlets in Jeddah. The ISO 6579:2002 standard was followed to isolate and identify Salmonella. The isolates were identified using cultural and biochemical features and were further confirmed using (MALDI-TOF MS). Antibiotic susceptibility for each Salmonella isolate was determined using the automated MicroScan WalkAway plus System.

Results

Out of the 112 samples, 35 (31.25%) samples harboured Salmonella spp. According to MALDI-TOF MS identification, 34 isolates were recognized as S. Typhimurium or S. Enteritidis with high confidence levels (log (score) values between 2.00 and 3.00), while one isolate was characterized as a Salmonella sp. with a low confidence level (log (score) < 2.00). The antibiotic sensitivity pattern demonstrated resistance to fluoroquinolones, cephalosporin, and penicillin, however, carbapenem was effective against all the isolated Salmonella spp. Out of the 35 isolates, 23 (65.71%) isolates resisted three or more than three different antibiotics and thus were regarded as multi-drug resistant (MDR) strains.

Conclusions

The findings of this study indicated the presence of MDR Salmonella species in chilled chicken marketed in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia which highlights potential public health risks. Accordingly, a thorough investigation of the veterinary service, safety and hygienic system of poultry industry, as well as vendors is needed to safeguard the consumer health.

Keywords

Antibiotic resistance

Jeddah

MALDI-TOF

Prevalence

Raw chicken

Salmonella

1 Introduction

Salmonella is one of the most common foodborne pathogens in the world, which belongs to the Enterobacteriaceae family. More than 2,600 different Salmonella serotypes have been found so far. It has been reported that nearly 99% of Salmonella serotypes can infect humans or animals (Choi et al., 2020). The annual mortality rate caused by Salmonella infections was estimated to be 370 thousands and nearly 115 million cases had been reported annually around the world. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), approximately, 1.35 million cases of salmonellosis, 26,500 hospitalisations, and 420 fatalities are caused by Salmonella each year in the United States (CDC, 2022, Chinello et al., 2020). Salmonella is second among the most frequent gastrointestinal infections in the European Union (EU) as a source of outbreaks of foodborne diseases (Chinello et al., 2020). According to the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), the annual cost of human salmonellosis could reach €3 billion (EFSA, 2020). The prevalence of salmonellosis in Saudi Arabia was 4.46 cases per 100,000 people in 2017, and it rose to 6.12 cases in 2018 (Abdulsalam and Bakarman, 2021).

Salmonella strains are the most common causes of foodborne illnesses (Gong et al., 2022) in humans and they are mainly transmitted by ingestion of contaminated meat (chicken, beef, turkey), eggs, or fruits (Wessels et al., 2021). Salmonellosis in humans can cause paratyphoid fever, typhoid fever, and nontyphoidal gastroenteritis, with symptoms like fever, diarrhoea, and stomach cramps (Gong et al., 2022). Occasionally, Salmonella also cause urinary tract, blood, bone, and joint infections (Kunwar et al., 2013). Several factors affect the severity of the disease, including the infection dose, gut flora, and immunity of the host. Severe salmonellosis is more likely to occur in young people, the elderly, and those with impaired immune systems (EFSA, 2020).

A poultry species may encompass chicken, duck, turkey, and laying hens; however, chicken account for about 88% of all poultry meat produced worldwide. Chicken meat contamination with foodborne pathogens continues to be a major economic and health issue around the world (Abatcha, 2017). There has been a rapid growth in the poultry industry in Kingdom of Saudi Arabia in the past thirty years. In 2020, there were 900,000 metric tons of poultry produced in Saudi Arabia, while 617,930 metric tons of poultry products were imported into the Kingdom (Mousa, 2021). The yearly average consumption of poultry products in Saudi Arabia reached around 50 kg per person (Moussa et al., 2010).

In Saudi Arabia, Salmonella is one of the leading causes of foodborne infections, and chicken meat is the principal source of the disease (MOH, 2019). The prevalence of Salmonella diseases varied from city to city in the Kingdom; Al-Ahsa (Al-Dughaym and Altabari, 2010), Riyadh (El-Tayeb et al., 2017). Reports indicated that the Salmonella isolates tested for conventional antibiotics showed resistance to the first-line antibiotics (El-Tayeb et al., 2017).

It is very difficult to eradicate Salmonella from the poultry production system as well as from its reservoirs, and food of animal origin is often the reservoir of this pathogen. Hence, a combination of appropriate biosecurity, management, and vaccination, as well as other prevention approaches including bacteriophages, can help to decrease Salmonella prevalence (Ricci and Piddock, 2010, Steenackers et al., 2012, Sylejmani et al., 2016). Disease outbreaks associated with Salmonella infection can be prevented with feed additives (Ukut et al., 2010). Antibiotics have been used to combat Salmonella, but their improper and/or excessive use has exacerbated the issue of multidrug resistance (Lenchenko et al., 2020).

The overuse of conventional antibiotics in treating animal and human diseases creates a risk since some strains of bacteria with AmpC. There have been β-lactamases isolated from animal and food products. Moreover, extended-spectrum cephalosporin-resistant Salmonella bacteria have recently been isolated from chicken carcasses (Al-Ansari et al., 2021). A second-line drug is required to treat the infections caused by such strains (Pan et al. 2018). Salmonella is, therefore, considered a “priority pathogen” by World Health Organization, (WHO) for which new therapies are required (Mousa, 2021).

Hence, the objectives of this investigation were to determine the incidence of Salmonella spp. in chilled chicken meat purchased from retail establishments in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, and to ascertain their antibiotic-resistance profiles. As part of the Saudi Vision 2030, the outputs and results of this study would be in the road map for poultry companies, chicken meat vendors, and other responsible bodies to safeguard the health of the society and to alleviate the economic burden associated with Salmonella infections.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Sample collection

A total of 112 chilled whole chicken carcass were procured from five local poultry companies at their retail outlets in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Each sample of a chicken carcass was put in a sterile plastic bag that was marked with the source and the date of collection. Collected samples were delivered in iceboxes immediately to the Microbiology Laboratory at the Department of Biological Sciences, King Abdulaziz University. After that, the samples were stored at 4 °C for future analysis.

2.2 Sample preparation and enrichment

A 25 g meat sample from each chicken carcass was put in a sterile stomacher bag in accordance with ISO 6579:2002 regulations. Thereafter, 225 ml of 2% buffered peptone water (Difco, Becton & Dickinson, MD, USA) was added to form a 1:10 dilution. The sample was then homogenised for 3 min at 2,000 rpm using a Stomacher 400 homogenizer (Seward Medical, England, UK). Following that, 10 ml of Rappaport-Vassiliadis-soya broth (RVS; Oxoid Ltd., UK, code: CM0866) was added to 1 ml of the pre-enriched sample, which was then incubated for 24 h at 41.5 °C. Thereafter, a 0.1 ml aliquot of the pre-enriched sample was added to 10 ml of Muller-Kauffmann Tetrathionate-Novobiocin Broth (MKTTn; Oxoid Ltd., UK, code: CM1048) and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C.

2.3 Isolation and characterization of Salmonella

10 µL aliquots of each prepared enriched sample were streaked onto Xylose Lysine Deoxycholate Agar (XLD; Oxoid Ltd., UK) and Brilliant Green Agar (BGA; Oxoid, Ltd., UK) plates and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. On BGA plates, salmonella colonies showed up as pinkish-white or red colonies with a red halo, and pink-red colonies with black centres on XLD plates. Individual representative colonies were picked up and sub-cultured until similar colonies were gained. From each plate, presumptive Salmonella colonies were chosen, and inoculated on nutrient agar, and cultivated for 24 h at 37 °C overnight. Gram's stain was used to evaluate the staining characteristics of the isolates and primary biochemical tests were carried out to identify the isolates at the genus level. Thereafter, each Salmonella isolate was preserved in 50% glycerol at 80 °C for further examination (El-Tayeb et al., 2017).

2.4 MALDI-TOF biotyper identification

Using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS; Bruker company Run identifier: 210221–1204-1011016777), presumptive Salmonella isolates were further identified at the species level (Dieckmann and Malorny, 2011). In this assay, individual presumptive Salmonella colonies were spread onto stainless steel MALDI plate, having Biotyper matrix solution. A pulsed laser then irradiates the loaded plate, causing desorption and extirpation of the sample and matrix material. In the hot column of the extracted gases, the molecules of the analyte are ionized to become deprotonated or protonated of ablated gases, and then they can be accelerated into the mass spectrometer for analysis (Dieckmann et al., 2008). The MALDI Biotyper CA System software was used to process the spectral data using the default settings. The smoothing, normalization, threshold exclusion, and peak selection were performed by the software, forming a list of a spectrum's most important peaks. The reference peak lists in the MALDI Biotyper database were compared to the peak lists produced from the MALDI-TOF mass spectra.

The final results were articulated as arithmetical score values between 0 and 3.00. An organism with a higher log (score) value has a higher similarity to an organism in the reference FDA-cleared database. The log (score) ≥ 2.00 is considered to be an excellent probability for the identification of a specific test organism at the species level (Singhal et al., 2015).

2.5 Test for antibiotic sensitivity

The test for the antibiotic sensitivity of the Salmonella isolates to conventional antibiotics was performed using an automated MicroScan WalkAway plus System with Gram-negative bacteria cards (Server version: 4.1.70 (PYTH) 48 2016–10-26_15-05–35). The interpretation of the results was as intermediate, resistant, or susceptible according to the breakpoints for each antibiotic.

2.6 The assay of the extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBLs) production

A combined disc test was performed to investigate the ESBL‐producing species for isolates that displayed a zone of inhibition of ≤ 22 mm, ≤ 25 mm, and ≤ 21 mm for ceftazidime, ceftriaxone, and aztreonam, respectively (Korzeniewska and Harnisz, 2013). The test was conducted as per CLSI guidelines (Wayane, 2016). The antimicrobials used were ceftazidime (30 μg), ceftazidime/clavulanic acid (30/10 μg), cefotaxime (30 μg), cefotaxime/clavulanic acid (30/10 μg), aztreonam (30 μg) and aztreonam/clavulanic acid (30/10 μg). CLSI criteria were used to interpret the results (Wayane 2016). A 5 mm increase in the zone of inhibition for combined drugs to ceftazidime, cefotaxime, or aztreonam was an indicator of ESBL‐producing species (Wayane 2016; Korzeniewska and Harnisz, 2013).

2.7 Computation of multiple antibiotic resistance (MAR) index

The multiple antibiotic resistance index (MARI) was calculated by dividing the number of antibiotics to which the isolate was resistant by the total number of antibiotics to which the isolate had been exposed (Apun et al., 2008). MARI ≥ 0.4 is associated with human fecal sources of contamination. MARI greater than 0.2 implies the origin of the isolates is most likely from areas where antibiotics are frequently used, while MARI ≤ 0.2 implies the origin of the bacteria is from areas wherever antibiotics are less frequently consumed (Thenmozhi et al., 2014).

2.8 Data management and statistical analysis

MS Excel was used for the recording of data and designing the graphs. The organized data was subsequently examined using IBM SPSS version 25.0. By dividing the number of positive samples by the total number of samples analyzed, the prevalence was estimated. To calculate the percentage of susceptible (S), intermediate (I), or resistant (R) strains, frequency and percentile descriptive statistics were utilized. A p-value of < 0.05 was regarded as a value of statistically significant.

3 Results

3.1 Assessment of Salmonella prevalence in retail chicken

Out of the collected 112 chicken meat samples, only 35 samples (31.3%) were positive for Salmonella based on the conventional identification via biochemical features. The Biotyper MALDI-TOF MS technology was used to further identify the isolates at the species level (Table 1). Out of the 35 Salmonella isolates submitted for MALDI-TOF MS, thirty four isolates had score values ≥ 2.0 and one isolate (sample no. 16) had 1.94 score. According to the MALDI-TOF-MS identification test, the 35 isolates were identified as Salmonella spp., S. Enteritidis or S. Typhimurium at high confidence levels (a log (score) value between 2.00 and 3.00), while one isolate was characterized as Salmonella sp. at a low confidence level (log (score) < 2.00). +++ (high confidence identification), + (low confidence identification).

Sample no. (code)

Log score value

Organism (best match)

Log score value

Organism (second best match)

Ranking

1 (R12)

2.20

Salmonella spp.

2.00

S. Typhimurium

+++

2 (M8)

2.21

Salmonella spp.

2.15

Salmonella spp.

+++

3 (M6)

2.38

Salmonella spp.

2.11

S. Enteritidis

+++

4 (R39)

2.40

Salmonella spp.

2.39

Salmonella spp.

+++

5 (M79)

2.37

Salmonella spp.

2.31

S. Typhimurium

+++

6 (R80)

2.17

S. Enteritidis

2.17

Salmonella spp.

+++

7 (M15)

2.47

Salmonella spp.

2.35

Salmonella spp.

+++

8 (R15)

2.34

Salmonella spp.

2.28

Salmonella spp.

+++

9 (M24)

2.21

S. Enteritidis

2.17

S. Typhimurium

+++

10 (R24)

2.29

Salmonella spp.

2.24

S. Typhimurium

+++

11 (R72)

2.27

S. Enteritidis

2.17

Salmonella spp.

+++

12 (R73)

2.30

S. Enteritidis

2.17

S. Typhimurium

+++

13 (M76)

2.23

Salmonella spp.

2.18

S. Enteritidis

+++

14 (M44)

2.33

S. Typhimurium

2.29

S. Enteritidis

+++

15 (R43)

2.03

Salmonella spp.

1.96

Salmonella spp.

+++

16 (M42)

1.98

Salmonella spp.

1.94

Salmonella spp.

+

17 (R42)

2.33

S. Enteritidis

2.29

S. Typhimurium

+++

18 (R40)

2.39

Salmonella spp.

2.31

S. Typhimurium

+++

19 (M40)

2.48

S. Typhimurium

2.46

Salmonella spp.

+++

20 (M64)

2.40

Salmonella spp.

2.38

S. Typhimurium

+++

21 (R64)

2.44

Salmonella spp.

2.37

S. Typhimurium

+++

22 (M60)

2.19

Salmonella spp.

2.14

S. Enteritidis

+++

23 (M62)

2.48

Salmonella spp.

2.31

S. Typhimurium

+++

24 (R62)

2.32

Salmonella spp.

2.23

S. Enteritidis

+++

25 (R59)

2.38

Salmonella spp.

2.21

S. Typhimurium

+++

26 (M47)

2.35

Salmonella spp.

2.29

Salmonella spp.

+++

27 (R47)

2.37

Salmonella spp.

2.29

Salmonella spp.

+++

28 (M45)

2.38

S. Typhimurium

2.37

Salmonella spp.

+++

29 (M66)

2.41

Salmonella spp.

2.34

S. Typhimurium

+++

30 (R66)

2.39

Salmonella spp.

2.38

Salmonella spp.

+++

31 (R67)

2.19

S. Enteritidis

2.15

Salmonella spp.

+++

32 (M68)

2.41

S. Typhimurium

2.41

Salmonella spp.

+++

33 (R68)

2.30

Salmonella spp.

2.35

S. Typhimurium

+++

34 (M69)

2.34

Salmonella spp.

2.27

Salmonella spp.

+++

35 (R69)

2.35

Salmonella spp.

2.34

S. Typhimurium

+++

The prevalence of Salmonella isolates varied across the five different poultry companies. The highest obtained Salmonella isolates were to company number 5 (n = 15, 42.9%) and the prevalence of each isolate was found to be 5.7%, 20%, and 17.1%, for Salmonella spp., S. Enteritidis, and S. Typhimurium, respectively (P < 0.05) (Table 2). On the contrary, out of all samples collected from company number 2, only 1 (2.9%) sample was Salmonella species, which is the lowest among all (Table 2).

Company no. (number of samples)

Number of positives for Salmonella of the total (%)

Number of Salmonella spp. (%)*

Number of S. Enteritidis (%)*

Number of S. Typhimurium (%)*

1 (23)

5 (4.5)

1 (2.9)

2 (5.7)

2 (5.7)

2 (23)

1 (0.9)

1 (2.9)

0

0

3 (22)

3 (2.7)

3 (8.6)

0

0

4 (22)

11 (9.8)

3 (8.6)

1 (2.9)

7 (20.0)

5 (22)

15 (13.4)

2 (5.7)

7 (20.0)

6 (17.1)

Total 112

35 (31.3%)

10 (28.6)

10 (28.6)

15 (42.9)

3.2 Antimicrobial sensitivity test

The previous 35 Salmonella isolates were evaluated for antibiotic susceptibility against a cohort of 18 different antibiotics from eight distinct classes (Table 3). Levofloxacin, ciprofloxacin, and all tested carbapenems (meropenem, imipenem, and ertapenem) were effective against every isolate. The maximum percentages of resistance (65.7%) was found for cefotaxime, and ampicillin and followed by ceftazidime (62.9%). Sixteen (45.7%) isolates were resistant to clavulanic Acid-Amoxicillin 4 (11.4%) isolates were resistant to ampicillin-subaclam, indicating that they were possible ESBL producers.

Class of antibiotics

Antibiotic tested

Resistant no. (%)

Intermediate no. (%)

Susceptible no. (%)

Folate pathway inhibitors

Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole

11 (31.4)

0

24 (68.6)

Glycylcycline

Tigecycline

1 (2.9)

12 (34.3)

22 (62.8)

Penicillin

Piperacillin and Tazobactam

0

1 (2.9)

34 (97.1)

Ampicillin

23 (65.7)

2 (5.7)

10 (28.9)

Fluoroquinolones

Norfloxacin

12 (34.3)

8 (22.9)

15 (42.9)

Levofloxacin

0

1 (2.9)

34 (97.1)

Ciprofloxacin

0

4 (11.4)

31 (88.6)

Carbapenems

Meropenem

0

0

35 (1 0 0)

Imipenem

0

0

35 (1 0 0)

Ertapenem

0

0

35 (1 0 0)

Cephalosporins

Cefuroxime

9 (25.7)

24 (68.6)

2 (5.7)

Ceftazidime

22 (62.9)

1 (2.9)

12 (34.3)

Cefotaxime

23 (65.7)

2 (5.7)

10 (28.6)

Cefazolin

9 (25.7)

24 (68.6)

2 (5.7)

Cefepime

7 (20)

0

28 (80)

Monobactams

Aztreonam

9 (25.7)

6 (17.1)

20 (57.1)

β-Lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations

Ampicillin-subaclam

4 (11.4)

13 (37.1)

18 (51.4)

Amoxicillin–clavulanic

16 (45.7)

0

19 (54.3)

3.3 Assessment of resistance profile of the isolated Salmonella species

Among the 35 Salmonella isolates subjected for sensitivity test, 23 (65.7%) isolates have shown resistance for three or more than three antibiotics belonging to different categories. Among these, 1 (2.9%), 3 (8.6%), 10 (28.6%), 6 (17.1%), and 3 (8.6%) isolates were resistant for three, four, five, eight and nine antibiotics, respectively (Table 4). In this regard, three isolates have shown resistance for nine antibiotics which is the highest pattern reported in this study. Of all the tested antibiotics, none of the isolates have shown resistance to carbapenems. The antibiotic resistance pattern indicated that some of the isolates showed similar resistance patterns as indicated in Table 4. Out of the tested Salmonella spp., eight species showed similar resistance patterns for five antibiotics (AMOX, AMP, CTX, CTZ, and MXF) (MARI = 0.28) and only one species displayed resistance to three antibiotics (MARI = 0.16). Similarly, three species displayed identical resistance patterns for four antibiotics (AMOX, AMP, CTX, and CTZ) (MARI = 0.22) and two isolates exhibited the same patterns for eight (MARI = 0.44) and nine (MARI = 0.5) antibiotics as presented in Table 4. MARI – multidrug resistance index, Amoxicillin clavulanate (AMOX), Ampicillin (AMP), Ampicillin-subaclam (FAM), Aztreonam (ATM), Cefazolin (CZN), Cefepime (CFPM), Cefotaxime (CTX), Ceftazidime (CTZ), Cefuroxime (CFX), Ciprofloxacin (CPFX), Ertapenem (ETP), Imipenem (IPM), Levofloxacin (LEVO), Meropenem (MER), Moxifloxacin (MXF), Piperacillin and Tazobactam (PIP), Tigecycline (TGC), Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TMP).

Sample no.

Level of resistance for the tested antibiotics

Number of isolates

Resistance profile

MARI

0

1

0

–

–

0

2

0

–

–

33

3

1 (2.9)

MXF, AMP, AMOX (1x)

0.16

3, 13, 31

4

3 (8.6)

AMOX, AMP, CTX, CTZ (3x)

0.22

4, 11, 12, 14, 15, 19, 23, 26, 34, 35

5

10 (28.6)

CZN, CTX, CTZ, CFX, TMP (1x)

AMOX, AMP, CTX, CTZ, MXF (1x)

AMOX, AMP, CTX, CTZ, MXF (8x)0.28

0

6

0

–

–

0

7

0

–

–

5, 16, 17, 18, 24, 30

8

6 (17.1)

FAM, ATM, CZN, FPM, CTX, CTZ, CFX, TMP (1x)

AMP, ATM, CZN, FPM, CTX, CTZ, CFX, TMP (2x)

AMP, ATM, CZN, CTX, CTZ, CFX, TMP (1x)

AMP, ATM, CZN, FPM, CTX, CTZ, CFX, MXF (1x)

AMP, ATM, CZN, FPM, CTX, CTZ, CFX, TMP (1x)0.44

25, 29, 32

9

3 (8.6)

FAM, AMP, ATM, CZN, FPM, CTX, CTZ, CFX, TMP (2x)

AMOX, FAM, AMP, ATM, CTX, CTZ, TGC, TMP, MXF (1x)0.5

Total number of resistant isolates (%) = 23 (65.7%)

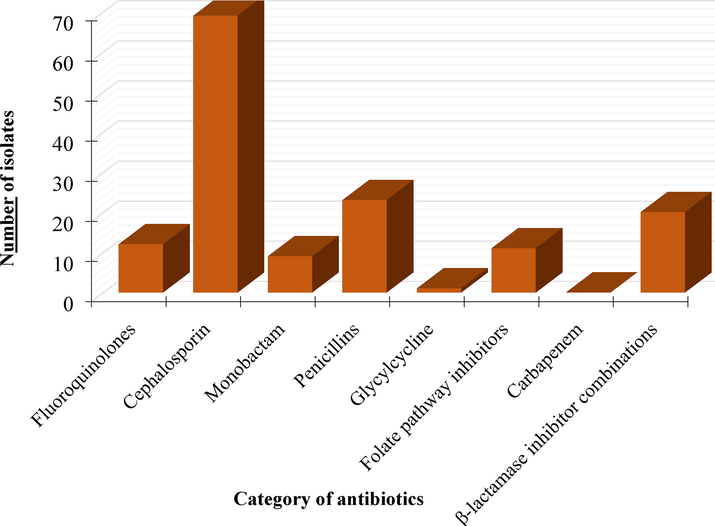

Among the eight classes of antibiotics tested, the highest number of resistances were developed to cephalosporins (n = 69) including cefuroxime (n = 9), ceftazidime (n = 21), cefotaxime (n = 23), cefepime (n = 7), and cefazolin (n = 9). In contrast, the lowest resistance was encountered for glycylcycline class of antibiotic (n = 1) (Fig. 1). All in all, 20 isolates were resistant to β-lactamase inhibitor combinations, 11 to folate pathway inhibitors, 23 to penicillin, 12 to fluoroquinolones.

The number of isolates showed resistance to five classes of antibiotics.

3.4 ESBLs production assay

Nine (25.7%) and eight (22.9%) isolates were found to be ESBL producers for ceftazidime, cefoxaxime and aztreonam, respectively. All these ESBL producers showed resistance to fourth-generation cephalosporin (cefepime) (Table 5). However, these isolates were susceptible to combinations of β-lactam/βlactamase inhibitors (amoxicillin-clavulanic acid and ampicillin-sulbactam). E, extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) producer; R, resistant; S, susceptible.

Sample No.

ESBLs production indicators

Fourth-generation cephalosporin

Ceftazidime (30 μg) and ceftazidime/clavulanic acid (30/10 μg)

Cefotaxime (30 μg) and cefotaxime/clavulanic acid (30/10 μg)

Aztreonam (30 μg) and Aztreonam /clavulanic acid (30/10 μg)

Cefepime

4

E

E

S

R

5

E

E

E

R

16

E

E

E

R

17

E

E

E

R

18

E

E

E

R

24

E

E

E

R

25

E

E

E

R

29

E

E

E

R

30

E

E

E

R

Total

9 (25.7%)

9 (25.7%)

8 (22.9%)

9 (25.7%)

4 Discussion

There is an ongoing challenge for many poultry production companies all over the world to control and/or prevent Salmonella infections. This is particularly true given the growing demand for poultry around the world. Hence, Salmonella outbreaks continue to be a serious hazard to the general public's health.

Since, chicken meat is a source for Salmonella, it is imperative to assess the prevalence of the disease all year round (Wessels et al., 2021). In addition, the development of multidrug-resistant Salmonella strains could potentially result in an invasive or acute infections, as well as treatment failures that could increase mortality, particularly in developing countries (Abatcha, 2017, MOH, 2019).

In the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, the Salmonella species are considered as one of the most prevalent bacteria causing food-borne diseases, especially during the Ummrah and Hajj seasons when many pilgrims are visiting the holy sites (USDA, 2020). From this perspective, in this study, we isolated different Salmonella spp. from five different chilled chicken retail outlets and were then identified at species level using MALDI-TOF MS. The overall prevalence was discovered to be 31.3%. Similarly, Badahdah and Aldagal (2018) reported a higher prevalence rate of Salmonella from local fresh chicken carcasses in Saudi Arabia with a magnitude of 69%. Contrary to what we found, a Riyadh-based investigation in Saudi Arabia indicated that out of 200 chilled chicken carcasses, only 2% were positive for Salmonella (Al-Ansari et al., 2021). Similarly, a low level of Salmonella was isolated from local frozen chickens in Riyadh, with the prevalence rate of 7.89% (Moussa et al., 2010). Similar studies which were conducted at two places, Calabar metropolis and Osogbo, in Nigeria indicated that the prevalence of Salmonella isolates was 11.1% (Ukut et al., 2010) and 2% (Adesiji et al., 2011), respectively. In a different study, low levels of Salmonella were reported from samples collected at chicken slaughterhouses in France and South Korea with the prevalence rates of 7.52% (Hue et al., 2011) and 3.7% (Yoon et al., 2014), respectively. The high level of prevalence noticed in our study was likely to be associated with some potential microbial contamination routes in poultry industry such as poor personnel and environmental hygiene, contamination during processing, fecal matter contamination during processing, leakage of intestinal content, and cross-contamination, improper transport and/or bird-to-bird pathogen transfer (Abdi et al., 2017).

Concerning the antibiotic sensitivity test, in this study, most of the isolates exhibited resistance to different categories of antibiotics, conversely, few isolates were found to be resistant to one class of antibiotics. Majority of the isolates were susceptible to carbapenem antibiotics, while most of them were resistant to cephalosporins. Our results agree with a former study conducted in China on samples originated from six different provinces (Wang et al., 2015). As a result of the extensive use of cephalosporin in animal’s food, foodborne pathogens have developed resistance to these antibiotics. In a recent study, Ibrahim and colleagues reported a high incidence of MDR E. coli and Salmonella spp. in broiler farmhouses in Malaysia. According to these authors, the noticed high prevalence was triggered by the overuse of antibiotics on the farms (Ibrahim et al., 2021).

It has been reported that most ESBL-producing bacterial species displayed co-resistance to additional antimicrobial agents, like tetracyclines, sulfonamides, aminoglycosides, and even to fluoroquinolones (Cantón and Coque, 2006). Our study results showed that 21 – 22% isolates were establish to be + Ve for production of ESBLs. These isolates displayed co-resistance to other antibiotics including the fourth-generation cephalosporin (Cefepime). According to recent reports, the importation of poultry products which may harbor antibiotic resistant pathogens like methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) and ESBL Salmonella spp. is a key task in the controlling of resistance against antibiotics (Van Loo et al., 2007).

It has also been found that Salmonella species are becoming more resistant to an important antibiotic that is nalidixic acid and less susceptible to fluoroquinolones (Aarestrup et al., 2003). As Salmonella can cause zoonotic infections and acquire genes horizontally from other bacteria (mainly enteric pathogens), its occurrence in different settings may result in a huge socio-economic burden for the public (Khademi et al., 2020).

5 Conclusions

In this investigation, we identified the prevalence and antibiotic susceptibility profile of Salmonella spp. isolated from chilled chicken flesh samples. The whole raw chicken samples, produced by five different poultry companies, were procured from local retailers in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. S. Typhimurium was found to be the most prevalent species isolated during the study periods. The current investigation also discovered that most of the isolates exhibited resistance to cephalosporin antibiotics, whereas, none of the isolates were resistant to carbapenems, suggesting that these antibiotics could be used for the treatment of the infections by the isolated Salmonella strains. Generally, the obtained data in the present study could be a foundation for further investigations in the Kingdom on the status of Salmonella both in animals and humans coupled with the antimicrobial resistance profile.

Acknowledgments

This research work was funded by Institutional Fund Projects under grant no (IFPRC-109-130-2020). Therefore, authors gratefully acknowledge technical and financial support from the Ministry of Education and King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Antimicrobial susceptibility and occurrence of resistance genes among Salmonella enterica serovar Weltevreden from different countries. J. Antimicrob. Chemother.. 2003;52:715-718.

- [Google Scholar]

- Salmonella and Listeria monocytogenes: a review of prevalence and antibiotic resistance in chickens and their processing environ-ments. Adv. Anim. Vet. Sci. 2017;5:395-403.

- [Google Scholar]

- Determination of the sources and antimicrobial resistance patterns of Salmonella isolated from the poultry industry in Southern Ethiopia. BMC Infect. Dis.. 2017;17:1-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Use of social media in food safety in Saudi Arabia—a preliminary study. AIMS Public Health. 2021;8:322.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of Arcobacter, Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus and Salmonella species in retail raw chicken, pork, beef and goat meat in Osogbo, Nigeria. Sierra Leone J. Biomed. Res.. 2011;3:8-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Isolation and molecular characterization of multidrug-resistant Salmonella enterica serovars. J. Infect. Public Health. 2021;14:1767-1776.

- [Google Scholar]

- Safety and quality of some chicken meat products in Al-Ahsa markets-Saudi Arabia. Saudi J. Biol. Sci.. 2010;17:37-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial susceptibilities of Escherichia coli isolates from food animals and wildlife animals in Sarawak, East Malaysia. Asian J. Anim. Veter. Adv.. 2008;3:409-416.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antibiotic resistance in Salmonella spp. isolated from local chickens in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. Eng.. 2018;8:127-130.

- [Google Scholar]

- CDC. 2022. Salmonella [Online]. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/salmonella/index.html [Accessed].

- Salmonella Hessarek Gastroenteritis with Bacteremia: a case report and literature review. Pathogens. 2020;9:656.

- [Google Scholar]

- Exploring the feasibility of Salmonella Typhimurium-specific phage as a novel bio-receptor. J. Anim. Sci. Technol.. 2020;62:668.

- [Google Scholar]

- Rapid classification and identification of salmonellae at the species and subspecies levels by whole-cell matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.. 2008;74:7767-7778.

- [Google Scholar]

- Rapid screening of epidemiologically important Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovars by whole-cell matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.. 2011;77:4136-4146.

- [Google Scholar]

- EFSA. 2020. Salmonella. https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/topics/topic/salmonella [Accessed September 7, 2020]

- Prevalence, serotyping and antimicrobials resistance mechanism of Salmonella enterica isolated from clinical and environmental samples in Saudi Arabia. Braz. J. Microbiol.. 2017;48:499-508.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence, serotype distribution and antimicrobial resistance of non-typhoidal salmonella in hospitalized patients in Conghua District of Guangzhou, China. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol.. 2022;12:805384

- [Google Scholar]

- Campylobacter contamination of broiler caeca and carcasses at the slaughterhouse and correlation with Salmonella contamination. Food Microbiol.. 2011;28:862-868.

- [Google Scholar]

- IBRAHIM, S., WEI HOONG, L., LAI SIONG, Y., MUSTAPHA, Z., CW ZALATI, C. S., AKLILU, E., MOHAMAD, M. & KAMARUZZAMAN, N. F. 2021. Prevalence of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) Salmonella spp. and Escherichia coli isolated from broilers in the East Coast of Peninsular Malaysia. Antibiotics, 10, 579

- Prevalence of fluoroquinolone-resistant Salmonella serotypes in Iran: a meta-analysis. Pathog. Global Health. 2020;114:16-29.

- [Google Scholar]

- Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-positive Enterobacteriaceae in municipal sewage and their emission to the environment. J. Environ. Manage.. 2013;128:904-911.

- [Google Scholar]

- Outbreak investigation: Salmonella food poisoning. Med. J. Armed Forces India. 2013;69:388-391.

- [Google Scholar]

- Poultry Salmonella sensitivity to antibiotics. Systemat. Rev. Pharm.. 2020;11:170-175.

- [Google Scholar]

- MOH (Ministry of Health), 2019. Foodborn Diseases Statistics (2018) [Online]. Available: https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/Ministry/MediaCenter/Publications/Pages/Publications-2019-11-12-001.aspx [Accessed September 7, 2022].

- MOUSA, H. 2021. Poultry and Products Annual, Saudi Arabia [Online]. Available: https://apps.fas.usda.gov/newgainapi/api/Report/DownloadReportByFileName?fileName=Poultry%20and%20Products%20Annual_Riyadh_Saudi%20Arabia_09-01-2021.pdf [Accessed].

- Using molecular techniques for rapid detection of Salmonella serovars in frozen chicken and chicken products collected from Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Afr. J. Biotechnol.. 2010;9

- [Google Scholar]

- Multiple food-animal-borne route in transmission of antibiotic-resistant Salmonella Newport to humans. Front. Microbiol.. 2018;9:23.

- [Google Scholar]

- Exploiting the role of TolC in pathogenicity: identification of a bacteriophage for eradication of Salmonella serovars from poultry. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.. 2010;76:1704-1706.

- [Google Scholar]

- MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry: an emerging technology for microbial identification and diagnosis. Front. Microbiol.. 2015;6:791.

- [Google Scholar]

- Salmonella biofilms: an overview on occurrence, structure, regulation and eradication. Food Res. Int.. 2012;45:502-531.

- [Google Scholar]

- Associations between the level of biosecurity and occurrence of Dermanyssus gallinae and Salmonella spp. in layer farms. Avian Dis.. 2016;60:454-459.

- [Google Scholar]

- Multi-drug resistant patterns of biofilm forming Aeromonas hydrophila from urine samples. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res.. 2014;5:2908.

- [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of bacteriological quality of fresh meats sold in Calabar metropolis, Nigeria. Electron. J. Environ., Agric. Food Chem.. 2010;9

- [Google Scholar]

- USDA (United States Department of Agriculture), 2020. Livestock and Poultry: World Markets and Trade. United States Department of Agriculture. Foreign Agriculture Service

- Emergence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus of animal origin in humans. Emerg. Infect. Dis.. 2007;13:1834.

- [Google Scholar]

- Molecular characterization of Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis on retail raw poultry in six provinces and two National cities in China. Food Microbiol.. 2015;46:74-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- WAYANE, P. 2016. Performance standard for antimicrobial susceptibility testing, clinical and laboratory standards institute (CLSI). 26th Informational supplement, Wayne, PA, USA, 33, M100-S23

- Salmonella in chicken meat: Consumption, outbreaks, characteristics, current control methods and the potential of bacteriophage use. Foods. 2021;10:1742.

- [Google Scholar]

- Potential of anaerobic digestion for material recovery and energy production in waste biomass from a poultry slaughterhouse. Waste Manag.. 2014;34:204-209.

- [Google Scholar]

Appendix A

Supplementary material

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2023.102684.

Appendix A

Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article: