Lagerstroemia speciosa extract ameliorates oxidative stress in rats with diabetic nephropathy by inhibiting AGEs formation

⁎Corresponding author at: Department of Zoology, College of Science, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. salkahtani@ksu.edu.sa (Saad Alkahtani)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Diabetes mellitus is amongst the most severe incurable diseases affecting a huge number of people everywhere in the world. Diabetic nephropathy (DN) is the main cause for kidney disease, possibly due to the lack of appropriate DN treatments. The current study is to assess the role of Lagerstroemia speciosa extract (LSE) in the mitigation of DN in a streptozotocin rat model of hyperlipidemia and hyperglycemia. The animal model of DN was induced in Sprague Dawley rats by administering streptozotocin and fed on a western diet for six weeks. The administration of LSE treatment at a dose of 400 mg/kg for six weeks. LSE showed a significant decline in enhanced biochemical parameters, for instance, glucose level, creatinine, and lipid profile. LSE treatment lowered the enhanced albumin level. The advanced glycation end-product level in kidneys was significantly reduced along with augmentation in the glutathione level and a decrease in lipid peroxidation. The inflammatory markers were also reduced considerably. Thus, LSE treatment effectively protects against streptozotocin-induced nephrotoxicity in rats. LSE might act as a possible adjuvant for DN therapy and needs to be investigated further.

Keywords

Lagerstroemia speciosa

Reactive oxygen species

Advanced glycation end products

Diabetic nephropathy

- LSE

-

Lagerstroemia speciosa extract

- DM

-

Diabetes mellitus

- CVD

-

Cardiovascular disease

- DN

-

Diabetic nephropathy

- AGEs

-

Advanced glycation end products

- RAGE

-

Receptor for advanced glycation end product

- TG

-

Triglyceride

- LDL

-

Low-density lipoprotein

- HDL

-

High-density lipoprotein

- VLDL

-

Very-low-density lipoprotein

- BUN

-

Blood urea nitrogen

- TNF-α

-

Tumour Necrosis Factor-α

- IL

-

Interleukin

- SOD

-

Superoxide dismutase

- MDA

-

Malondialdehyde

- GSH

-

Reduced glutathione

- ROS

-

Reactive oxygen species

- BW

-

Body weight

- KW

-

Kidney weight

- KH

-

Kidney hypertrophy

- BG

-

Blood glucose

Abbreviations

1 Introduction

The worldwide incidence of diabetes mellitus (DM) has risen dramatically in adults in recent years. The 7th edition of DM Atlas released in 2015 estimated 415 million adults having DM globally. It is expected that 693 million people will live with DM by 2045 (Skyler, 2012). DM is a chronic metabolic condition related to long-term damage and multiple organ failures (Organization, 2007). It is a metabolic condition triggered by insulin tolerance by pancreatic cells. DM is the more extreme of the two forms. Obesity induces DM, which is considered by raised serum insulin levels and hyperlipidemia (Kissebah et al., 1982; Krotkiewski et al., 1983). DM is impossible to cure entirely, nevertheless it can be controlled and the progression is reduced by managing optimum BG levels. However, a growing number of diabetic patients are transitioning to natural ingredients to support their current care plans.

Nephropathy has been confirmed to affect the individuals suffering from high blood sugar for long period and affects kidneys (Schena and Gesualdo, 2005; Tanios and Ziyadeh, 2012). Both functional and structural defects comprise diabetic nephropathy (DN) (Forbes et al., 2008).

Lagerstroemia speciosa is widely distributed globally. It is found in the Philippines, India, and Malaysia (Kotnala et al., 2013). Lagerstroemia Speciosa has traditionally been used as medicine to cure illnesses and ailments. The leaves are being used as a diuretic, decongestant, and used to treat DM (Chan et al., 2014). The red–orange leaves contain a lot of corosolic acid, which helps to lower BG. Its fresh leaves are also used to treat the wound and sanitize the skin's surface. Roots are utilized to treat mouth ulcers, while the bark is used as a stimulant, pain reliever. The leaves of Lagerstroemia Speciosa are used to make herbal tea in the Philippines to help lower BG levels, lose weight and to cure of diabetes (Chan et al., 2014).

Supplementing certain nutritional antioxidants, like flavonoids, vitamins E and C, is the existing way of decreasing oxidative damage in DM (Raafat and Samy, 2014). Herbal drugs are being used for the treatment of several human diseases. Furthermore, the market for herbal products is growing regularly.

2 Animals

Healthy male rats weighing 250–300 g were obtained from the animal facility at Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University (PNU), Saudi Arabia. All animals were maintained in polypropylene cages under standard environmental conditions (25 ± 2 °C and 50 ± 10% RH at 12 h light/dark cycle). Animal experiments were carried out in accordance with the guidelines of the PNU Institutional Review Board and approved by Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Saudi Arabia – IRB log No. 20-0336. Throughout the experiment, the animals were allowed water and food ad libitum.

2.1 Animal study

The rats were administered with a low dose of streptozotocin (STZ, 35 mg/kg) injection along with a high-fat diet (Research Diet, USA) to develop diabetes in rats (Srinivasan et al., 2005; Syed et al., 2021, 2020). This high-fat diet was fed for three months to the diseased group as well as to the treatment group. The researchers used an extract made from dried Lagerstroemia Speciosa leaves. For eight weeks, rats were given LSE in the form of an oral dose. The animals were grouped into three groups (n = 6): normal control group, STZ-induced diabetic group, STZ-induced diabetic group treated with LSE 400 mg/kg.

2.2 Determination of body weight BW and kidney index

The body weight BW and kidney weight KW were determined using a weighing balance and kidney weight to body weight ratio was determined to determine kidney hypertrophy KH.

2.3 Determination of fasting glucose BG, fasting insulin level

Fasting glucose BG was estimated by glucometer. The level of insulin was estimated by using the Rat Insulin ELISA Kit as per the manufacturer's protocol (Syed et al., 2021, 2020).

2.4 Determination of biochemical parameters

The plasma level of triglyceride TG, low-density lipoprotein LDL, and high-density lipoprotein HDL was estimated by colorimetric assay kit, as per manufacturer's instruction. The kidney function was estimated by measuring blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, and albumin level by albumin assay kit according to the manufacturer's protocol. Renal inflammation was assessed by measuring the expression as well as the level of Tumour Necrosis Factor-α TNF-α, Interleukin-6 IL-6, and IL-β by using respective ELISA kits as per the manufacturer's protocol.

2.5 Estimation of the advanced glycation end product (AGEs)

The advanced glycation end product AGEs level was determined in kidney homogenate according to the manufacturer's protocol of the ELISA kit (Shanghai Biotech, China).

2.6 Determination of oxidative stress markers and reactive oxygen species (ROS)

The level of reduced glutathione (GSH) and malondialdehyde (MDA) were estimated in kidney tissue as described previously (Prabhakar et al., 2012). Reactive oxygen species ROS was determined in kidney tissue according to the method described previously (Syed et al., 2016b).

2.7 Real-time PCR

To determine the effect of the extract on the mRNA expression, we performed real-time qPCR employing kidney tissue (Syed et al., 2016a, 2016b).

2.8 Statistical analysis

Results were expressed as Mean ± SEM. One-way ANOVA was used followed by Tukey's multiple comparisons tests by GraphPad Prism 8.0 software. P < 0.05 value was set as statistically significant.

3 Results

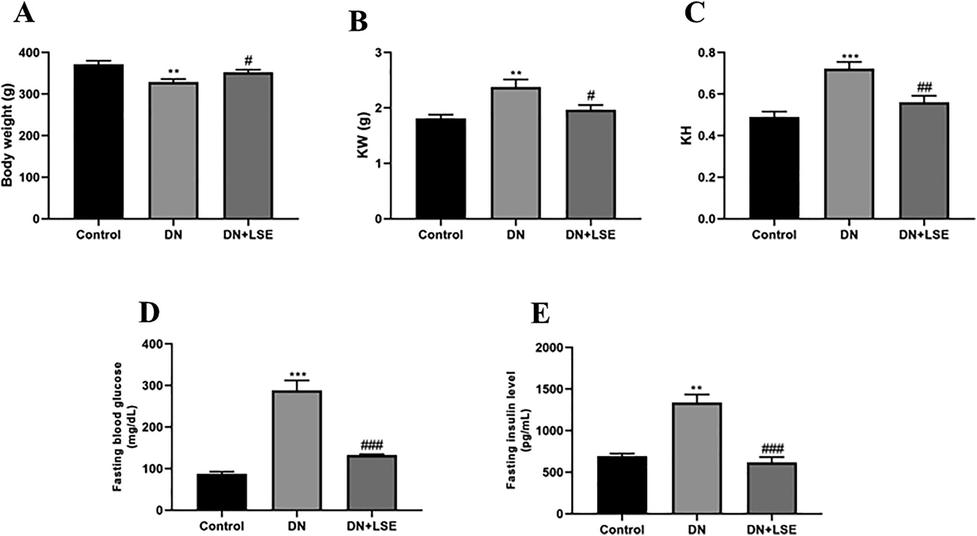

3.1 Effect of LSE on body weight, kidney weight, and kidney hypertrophy

Diabetic nephropathy DN group rats exhibited a significant reduction in body weight compared to control rats (Fig. 1A). Kidney weight (Fig. 1B) and kidney hypertrophy (Fig. 1C) were significantly enhanced in the DN group. On treatment with Lagerstroemia speciosa extract LSE, it maintains body weight and decreases kidney weight and kidney hypertrophy

- Effect of LSE on (A) body weight (B) kidney weight KW (C) kidney hypertrophy KH (D) fasting blood glucose BG level and (E) fasting insulin level. Data are shown as Mean ± S.E.M, *Control vs DN; #DN vs DN + LSE. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001.

3.2 Effect of LSE on fasting BG, and insulin level

The level of fasting glucose BG level was enhanced in the DN group rats. On treatment with LSE, it significantly decreased the fasting BG (Fig. 1D) and insulin level (Fig. 1E).

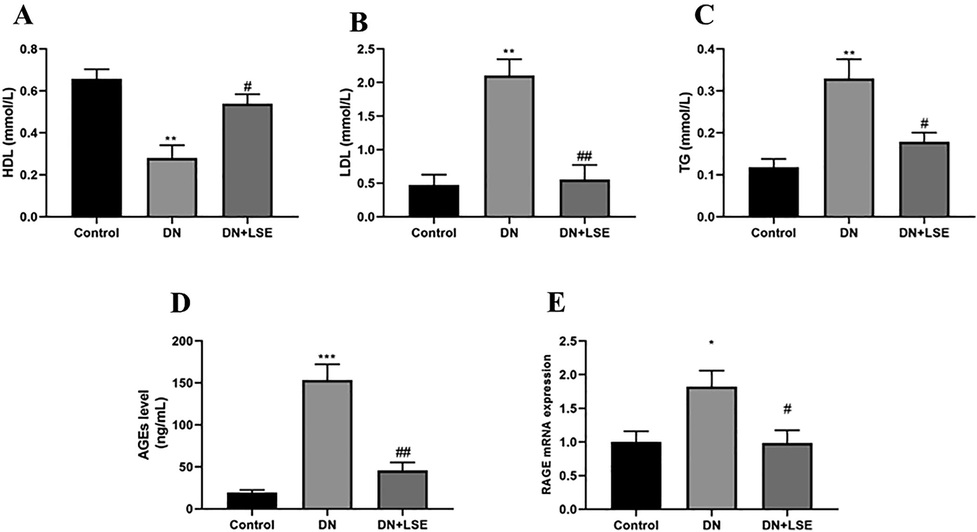

3.3 Effect of LSE on lipid profile

The level of HDL in the DN group was comparatively decreased while the LDL, TG level was significantly augmented as compared to the control group. On the administration of LSE, the level of HDL cholesterol was significantly enhanced, whereas LDL, TG level was markedly lowered as compared to the DN group rats (Fig. 2A–C).

- Effect of Lagerstroemia speciosa extract LSE on (A) High-density lipoprotein HDL (B) Low-density lipoprotein LDL (C) Triglyceride TG (D) Advanced glycation end product AGEs level (E) mRNA of receptor for advanced glycation end product RAGE expression. Data are shown as Mean ± S.E.M, *Control vs DN; #DN vs DN + LSE. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001.

3.4 Effect of LSE on AGEs level

The AGEs level in kidney tissue was significantly higher in the diseased group rats but not in control rats. In contrast, extract-treated rats revealed a significantly lower level of AGEs (Fig. 2D).

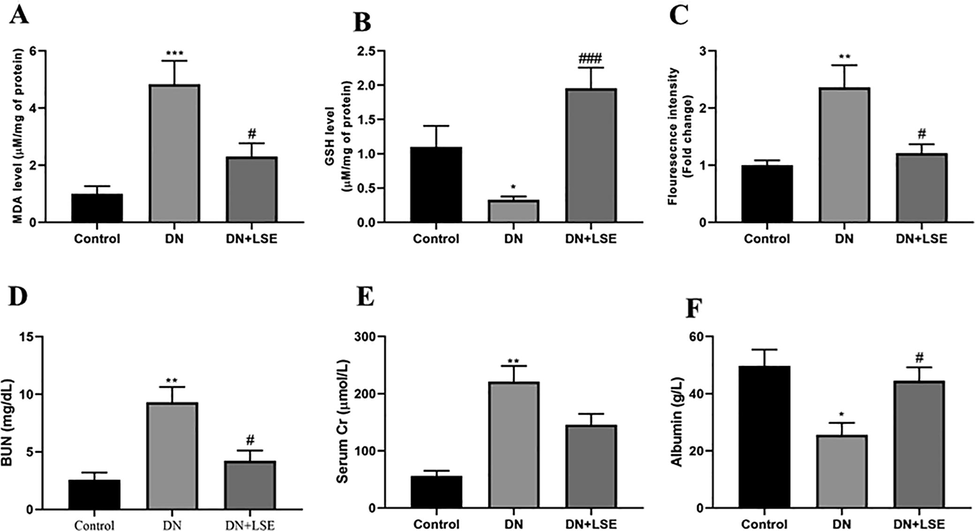

3.5 Effect of LSE on oxidative stress and ROS production

In the DN group, there is an augmented level of MDA (Fig. 3A), ROS (Fig. 3C), and a decreased level of GSH (Fig. 3B) level. Treating with LSE reduced ROS production, MDA Level, and enhanced the level of GSH.

- Effect of Lagerstroemia speciosa extract LSE on (A) Malondialdehyde MDA level and (B) Reduced glutathione GSH level (C) ROS production (D) Blood urea nitrogen BUN (E) Serum creatinine level and (F) Albumin level. Data are shown as Mean ± S.E.M, *Control vs DN; #DN vs DN + LSE. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001.

3.6 Effect of LSE on renal dysfunction

The serum level of creatinine and BUN was significantly augmented, whereas the albumin level was significantly lowered in DN group rats. On treatment with LSE, it reduced the blood urea nitrogen (Fig. 3D) creatinine level (Fig. 3E) and enhanced the level of albumin (Fig. 3F) as compared to the DN group rats.

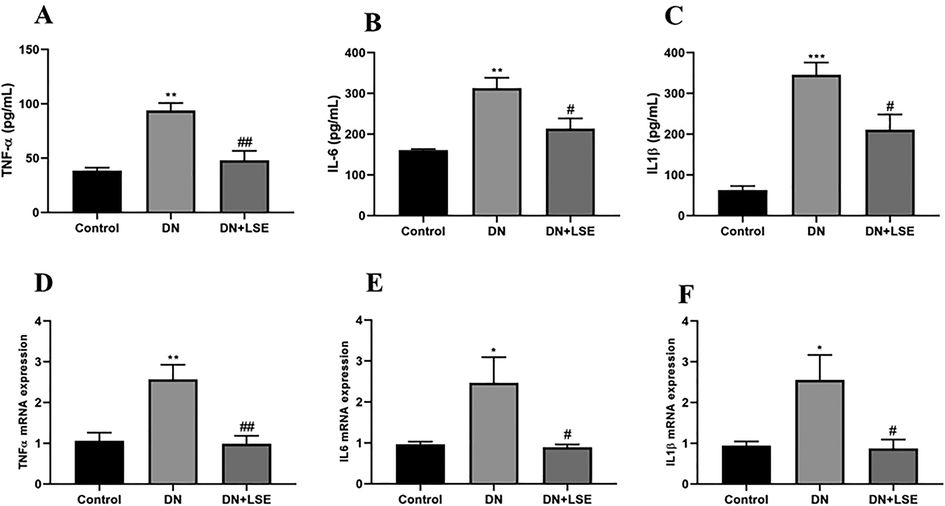

3.7 Effect of LSE on renal inflammation

The renal inflammation was evaluated by the estimation of inflammatory cytokines in the circulation and kidney tissue. The plasma level and the gene expression of inflammatory cytokine markers, such as TNFα, IL6, and IL1β revealed significantly elevated levels in DN group rats while their level was significantly declined by treatment with LSE (Fig. 4A–F).

- Effect of LSE on inflammatory markers (A) Tumour Necrosis Factor-α TNF-α, (B) Interleukin-6 IL-6, (C) Interleukin-1β IL-1β, (D) mRNA TNF-α expression, (E) mRNA IL6 expression, and (F) mRNA IL-1β expression. Data are shown as Mean ± S.E.M, *Control vs DN; #DN vs DN + LSE. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001.

4 Discussion

DN is amongst the foremost causes of DM and the major reason for end-stage renal failure in the world today (Olatunji et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2011). Despite the progression of therapeutic agents that inhibit DN development, there has also been a dramatic rise in herbal drugs' use to prevent this complication from occurring (Cai et al., 2010; Tabatabaei-Malazy et al., 2015). In our present investigation, we have shown the use of herbal medicines in the medication for diabetic complications.

STZ is a susceptible organ lesion inducer in rodents. It kills pancreatic β-cells that cause enhanced blood glucose levels and kidney damage. Thus, it demonstrates a useful animal model to validate natural herbal drugs' therapeutic effect on in vivo diabetes-related renal impairment (Xu et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2013). The research investigations have revealed that a substantial increase in fasting BG levels can be explained by stimulating residual pancreatic processes, regenerating or protecting pancreatic cells that STZ has partially killed. Thus potentiating the release of insulin from β-cells and probably growing peripheral glucose utilization (Aybar et al., 2001; Chuengsamarn et al., 2012). Lagerstroemia Speciosa leaves, bark, and roots have traditionally been used to treat a variety of illnesses and ailments. The leaves are used as diuretic, decongestant, and used to treat DM (Chan et al., 2014). The red–orange leaves contain a lot of corosolic acid, which helps to lower BG. Its fresh leaves are also used to treat wound and sanitize the skin's surface. Roots are used to treat mouth ulcers, while bark is used as a stimulant, pain reliever. The leaves of Lagerstroemia Speciosa are used to make herbal tea in the Philippines to help lower BG levels, lose weight and cure diabetes (Chan et al., 2014).

Researchers have suggested various pathways for plants having phenolic compounds, such as pancreatic β-cells protection from ROS, increased insulin secretion, higher susceptibility of peripheral tissues to insulin reactions, and decreased GI glucose absorption (Dragan et al., 2015; Sabu et al., 2002). DM is caused by a lack of insulin. Owing to an osmotic difference, sugar is present in the urine and an enhanced volume of excreted urine when BG levels are increased than the renal filtration rate. The animals become insulin resistant as it was also fed with high-fat diet, causing hyperinsulinemia (Singh et al., 2020; Syed et al., 2021). In diabetic animals, this mechanism can be detected. LSE (400 mg/kg) was administered for 40 days and we found improved body weight, BG (Fig. S1) equivalent to metformin, significantly reduced insulin and lipid level.

Over-production of AGEs in increased blood sugar conditions in the body, acts as an important role in the DN pathogenesis during diabetes (Chen et al., 2020; Syed et al., 2020). In the production of DN, the synthesis of AGEs in kidney is important. AGEs have a long-term effect on proteins and lipids, triggering disruption to blood vessels including kidneys (Ojima et al., 2015; Wang and Zhao, 2019). Diabetic rats have AGEs in nearly all of their tissues. Furthermore, kidneys are much more prone to the accumulation of AGE than other body tissue (Tan et al., 2007). The aggregation of AGEs is the only element that causes anatomical defects in DN rodents' kidneys (Forbes et al., 2003; Makita et al., 1991; Yamagishi and Matsui, 2011). Suppression of the formation of AGEs can be a promising treatment process in the control of DN. LSE seems to have a modulatory effect on the development of AGEs. Furthermore, hyperglycemic rats' serum contained higher concentrations of AGEs, which were decreased after intervention with LSE. Flavonoids have also been shown to reduce AGEs and blood pressure and reduce AGEs receptor (RAGE) expression (Hou et al., 2017; Palma-Duran et al., 2018). The flavonoid content in LSE extracts. It may have the potential for the decreasing the AGEs formation, ROS and OS. Thus, LSE safeguards the kidney by reducing the AGEs formation in diabetic rats.

The impairment of the polyol pathway caused by high blood sugar induces OS, which is a strong regulator of chronic diseases, as well as DN (Shen and Wang, 2020). The enhanced production of ROS has been linked to chronic diseases. Multiple physiological pathways, including the AGEs, PKC, and hexosamine mechanisms, alter the cell's redox potential and increase the production of ROS directly or indirectly. STZ induces diabetes by enhancing the development of ROS and suppressing OS enzymes as well as ROS (Makinde et al., 2020). Lipid peroxidation (LPO) indicators were present in higher concentrations in the kidneys, livers. These increased levels of lipid peroxidation can be linked to a rise in free radicals production in diabetic, and is mostly induced by elevated BG levels (Khattab et al., 2020). The high antioxidant capacity of medicinal plants, particularly those with a high polyphenol compound content, has been confirmed, and these antioxidants have developed significantly.

DN is related both to impaired glucose metabolism and dyslipidemia, which is typically present in DM. People with diabetes are predisposed to heart diseases and other coronary heart disease complications due to lipid abnormalities (Abo-Salem et al., 2009; Bagheri Yazdi et al., 2020). Increased BG level, and dyslipidemia are chief causes of heart disease-related to interrelation with free radical generation. There was abnormal level of lipid profile, this dyslipidemia is caused by more breakdown of lipid and free fatty (Gao et al., 2010). Furthermore, dyslipidemia, which is featured by enhanced levels of TG and FFAs, induces oxidative damage, and can aggravate the negative effects of hyperglycemia on its own (Navarro-González et al., 2011; Rosario and Prabhakar, 2006). Administration of LSE significantly improves the lipid profile.

Elevated serum creatinine, BUN, and hypertrophy of the kidneys are all DN symptoms (Kanwar et al., 2008; Lemann et al., 1990). The hyperglycemia will worsen glomerulosclerosis and hasten the development of DM. These modifications are a result of poor glucose balance, renal tissue damage, and elevated ROS (Al Hroob et al., 2018). A number of renal function abnormalities, such as basement membrane thickening, characterize DN. DM and high kidney function levels cause these side effects (Thomas et al., 2005). Management of diabetic group with LSE treatment reduced the level of kidney function test, representing improved renal clearance. Diabetic animals' average renal weight was found to be increased than that of normal control rats. Whereas on comparison with the normal control data, the intake of LSE substantially reduced the renal hypertrophy.

5 Conclusion

The anti-hyperglycemic activity of LSE decreased the kidney lesions and the OS. The findings additionally indicated that LSE has an innate capacity to prevent the formation of AGEs. It can be suggested that LSE has a renoprotective function in STZ-induced DN in rats by reducing hyperglycemia, OS, and DN markers. As a consequence, our findings add to our understanding of DN clinical interventions.

6 Availability of data and materials

The data generated or analyzed in this article are online publicly available without request.

Acknowledgement

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deputyship for Research & Innovation, Ministry of Education in Saudi Arabia for funding this research work through the project number PNU-DRI-RI-20-035.

References

- Experimental diabetic nephropathy can be prevented by propolis: effect on metabolic disturbances and renal oxidative parameters. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci.. 2009;22:205-210.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ginger alleviates hyperglycemia-induced oxidative stress, inflammation and apoptosis and protects rats against diabetic nephropathy. Biomed. Pharmacother.. 2018;106:381-389.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hypoglycemic effect of the water extract of Smallantus sonchifolius (yacon) leaves in normal and diabetic rats. J. Ethnopharmacol.. 2001;74(2):125-132.

- [Google Scholar]

- The role of Artemisia turanica extract on renal oxidative sand biochemical markers in STZ-induced diabetes in rat. Avicenna J. Phytomed. 2020

- [Google Scholar]

- Zhen-wu-tang, a blended traditional Chinese herbal medicine, ameliorates proteinuria and renal damage of streptozotocin-induced diabetic nephropathy in rats. J. Ethnopharmacol.. 2010;131(1):88-94.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phytochemistry and pharmacology of Lagerstroemia speciosa: A natural remedy for diabetes. Int. J. Herb. Med.. 2014;2:100-105.

- [Google Scholar]

- Loganin and catalpol exert cooperative ameliorating effects on podocyte apoptosis upon diabetic nephropathy by targeting AGEs-RAGE signaling. Life Sci.. 2020;252:117653.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Curcumin extract for prevention of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(11):2121-2127.

- [Google Scholar]

- Polyphenols-rich natural products for treatment of diabetes. Curr. Med. Chem.. 2015;22:14-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Role of advanced glycation end products in diabetic nephropathy. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol.. 2003;14(suppl 3):S254-S258.

- [Google Scholar]

- Oxidative stress as a major culprit in kidney disease in diabetes. Diabetes. 2008;57(6):1446-1454.

- [Google Scholar]

- Rhein improves renal lesion and ameliorates dyslipidemia in db/db mice with diabetic nephropathy. Planta Med.. 2010;76(01):27-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- Salvianolic acid A protects against diabetic nephropathy through ameliorating glomerular endothelial dysfunction via inhibiting AGE-RAGE signaling. Cell. Physiol. Biochem.. 2017;44(6):2378-2394.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diabetic nephropathy: mechanisms of renal disease progression. Exp. Biol. Med.. 2008;233(1):4-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- Olive leaves extract alleviate diabetic nephropathy in diabetic male rats: impact on oxidative stress and protein glycation. Int. J. Pharm. Res. Allied Sci. 2020;9:130-141.

- [Google Scholar]

- Relation of body fat distribution to metabolic complications of obesity. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab.. 1982;54(2):254-260.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lagerstroemia species: a current review. Int. J. Pharm. Technol. Res.. 2013;5:906-909.

- [Google Scholar]

- Impact of obesity on metabolism in men and women. Importance of regional adipose tissue distribution. J. Clin. Invest.. 1983;72(3):1150-1162.

- [Google Scholar]

- Use of the serum creatinine to estimate glomerular filtration rate in health and early diabetic nephropathy. Am. J. Kidney Dis.. 1990;16(3):236-243.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fatty acids and sterol rich stem back extract of shorea roxburghii attenuates hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia, and oxidative stress in diabetic rats. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol.. 2020;122(11):2000151.

- [Google Scholar]

- Advanced glycosylation end products in patients with diabetic nephropathy. N. Engl. J. Med.. 1991;325(12):836-842.

- [Google Scholar]

- Inflammatory molecules and pathways in the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy. Nat. Rev. Nephrol.. 2011;7(6):327-340.

- [Google Scholar]

- Empagliflozin, an inhibitor of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 exerts anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic effects on experimental diabetic nephropathy partly by suppressing AGEs-receptor axis. Horm. Metab. Res.. 2015;47(09):686-692.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lycium chinense leaves extract ameliorates diabetic nephropathy by suppressing hyperglycemia mediated renal oxidative stress and inflammation. Biomed. Pharmacother.. 2018;102:1145-1151.

- [Google Scholar]

- Organization, W.H., 2007. Diabetes programme facts and figures. http//www. who. int/mediacentre/factsheets.

- Serum levels of advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) and the decoy soluble receptor for AGEs (sRAGE) can identify non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in age-, sex- and BMI-matched normo-glycemic adults. Metabolism. 2018;83:120-127.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Oxidative stress induced by aluminum oxide nanomaterials after acute oral treatment in Wistar rats. J. Appl. Toxicol.. 2012;32(6):436-445.

- [Google Scholar]

- Raafat, K., Samy, W., 2014. Amelioration of diabetes and painful diabetic neuropathy by Punica granatum L. Extract and its spray dried biopolymeric dispersions. Evidence-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2014.

- Sabu, M.C., Smitha, K., Kuttan, R., 2002. Anti-diabetic activity of green tea polyphenols and their role in reducing oxidative stress in experimental diabetes. J. Ethnopharmacol. 83, 109–116.

- Pathogenetic mechanisms of diabetic nephropathy. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol.. 2005;16(3 suppl 1):S30-S33.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of glutathione liposomes on diabetic nephropathy based on oxidative stress and polyol pathway mechanism. J. Liposome Res. 2020:1-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Heliyon Combination of Pancreastatin inhibitor PSTi8 with metformin inhibits Fetuin-A in type 2 diabetic mice. Heliyon. 2020;6(10):e05133.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Skyler, J., 2012. Atlas of diabetes. Springer Science & Business Media.

- Combination of high-fat diet-fed and low-dose streptozotocin-treated rat: a model for type 2 diabetes and pharmacological screening. Pharmacol. Res.. 2005;52(4):313-320.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cardioprotective effect of ulmus wallichiana planchon in β-adrenergic agonist induced cardiac hypertrophy. Front. Pharmacol.. 2016;7:510.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of anti-hypertensive activity of Ulmus wallichiana extract and fraction in SHR, DOCA-salt-and L-NAME-induced hypertensive rats. J. Ethnopharmacol.. 2016;193:555-565.

- [Google Scholar]

- Inhibition of NOX4 by Cissus quadrangularis extract protects from Type 2 diabetes induced-steatohepatitis. Phytomed. Plus. 2021;1(1):100021.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Naringin ameliorates type 2 diabetes mellitus-induced steatohepatitis by inhibiting RAGE/NF-κB mediated mitochondrial apoptosis. Life Sci.. 2020;257:118118

- [Google Scholar]

- Trends in publication on evidence-based antioxidative herbal medicines in management of diabetic nephropathy. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord.. 2015;15:1.

- [Google Scholar]

- AGE, RAGE, and ROS in diabetic nephropathy. Seminars in Nephrology. Elsevier. 2007;27(2):130-143.

- [Google Scholar]

- Emerging therapies for diabetic nephropathy patients: beyond blockade of the renin-angiotensin system. Nephron Extra. 2012;2(1):278-282.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tubular changes in early diabetic nephropathy. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis.. 2005;12(2):177-186.

- [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.G., Lu, X.H., Li, W., Zhao, X., Zhang, C., 2011. Protective effects of luteolin on diabetic nephropathy in STZ-induced diabetic rats. Evidence-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2011.

- Corn silk (Zea mays L.), a source of natural antioxidants with α-amylase, α-glucosidase, advanced glycation and diabetic nephropathy inhibitory activities. Biomed. Pharmacother.. 2019;110:510-517.

- [Google Scholar]

- Puerarin, isolated from Pueraria lobata (Willd.), protects against diabetic nephropathy by attenuating oxidative stress. Gene. 2016;591(2):411-416.

- [Google Scholar]

- Advanced glycation end products (AGEs), oxidative stress and diabetic retinopathy. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol.. 2011;12:362-368.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phycocyanin and phycocyanobilin from Spirulina platensis protect against diabetic nephropathy by inhibiting oxidative stress. Am. J. Physiol. Integr. Comp. Physiol.. 2013;304(2):R110-R120.

- [Google Scholar]

Appendix A

Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2021.101493.

Appendix A

Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article: