Translate this page into:

Kinetics of the catalytic oxidation of toluene over Mn,Cu co-doped Fe2O3: Ex situ XANES and EXAFS studies to investigate mechanism

⁎Corresponding authors. diendv@hufi.edu.vn (Van Dien Dang), bpandit@ing.uc3m.es (Bidhan Pandit), niraj.jha@sharda.ac.in (Niraj Kumar Jha)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Abstract

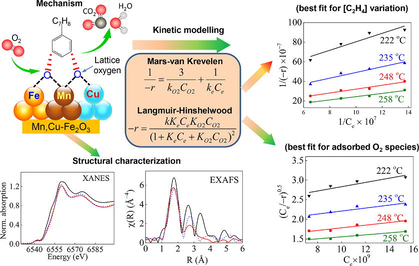

In this study, the catalytic mechanism of Mn,Cu-Fe2O3 catalyst was directly determined through reaction kinetics coupled with surface characterization. The impact of operating conditions on the catalytic performance of Mn,Cu-Fe2O3 nanocomposite for toluene oxidation in a continuous fixed-bed reactor was investigated. It was found that Mn,Cu-Fe2O3 catalyst gave the best catalytic performance in toluene removal when the initial concentrations of toluene and oxygen were at 165 ppmv and 10% at a flow rate of 200 mL min−1, respectively. Subsequently, Power-law, Mars-van Krevelen, and Langmuir-Hinshelwood models were developed to describe the kinetics of the total toluene oxidation for both toluene- and oxygen-dependent mixtures in a range of temperatures. According to the results, the basic Power-law model could not properly represent the kinetics of toluene oxidation over the catalyst. Meanwhile, the Mars-van Krevelen model allows for determining the kinetic mechanism under the variation of C7H8 concentration. The Langmuir-Hinshelwood model is attainable to express the kinetics of the oxygen-involved reaction mechanism. Moreover, the change in the structure of Mn,Cu-Fe2O3 catalyst after the catalytic reaction was characterized by X-ray Absorption Near-edge Structure (XANES) and Extended X-ray Absorption Fine Structure (EXAFS) measurements to confirm the catalytic mechanism determined through reaction kinetics. The achieved results suggest the possibility of using various models to justify the correlation between model-simulated and experimental data for VOCs oxidation in a continuous-flow catalytic reactor.

Keywords

Catalytic oxidation

Toluene

Kinetics

Langmuir-Hinshelwood

Mars-van Krevelen

1 Introduction

Volatile organic compounds (VOCs), known as carcinogenic pollutants, are released through various sources such as solvents, fossil fuel thermal power plants, and transportation. They are precursors for the formation of photochemical smog and particulate matter, which threaten human health and the environment (Zhang et al., 2020). Although noble metals (Pt, Au, Pd) are highly active for catalytic oxidation of toluene and other VOCs oxidation, the high synthesizing cost and difficult regulation of particle size restrain their large-scale application (Zang et al., 2019). Hence, low-cost transition metal oxides-based (i.e., Mn, Cu, Ce, Ti, Co) catalysts are recognized as alternative materials because of their high activity and poisoning counteraction (Figueredo et al., 2020; Li et al., 2021). In addition to the catalyst composition, kinetic model derivation, which makes it possible to foresee the reaction rate of VOCs combustion over the catalyst, is another factor that must be considered for the catalytic combustion technique. Various conceptual models defining the surface mechanism were theorized in the quest to construct reliable kinetic models for the catalytic oxidation processes (Mohammed et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2023).

Moreover, it may be hard to explain the catalytic mechanism of the as-prepared material under reaction conditions, especially in the existence of various reactants and their interaction with the catalyst’s surface (He et al., 2020; Lin et al., 2023). To our best knowledge, current kinetic expression is not available for describing the oxidation route as well as the catalytic mechanism. Therefore, constructing suitable kinetic models to contrast the experimental data of the oxidation pathway is needed to support the catalytic mechanism. Accordingly, kinetic modeling can provide a detailed understanding of the oxidation reaction rate and the effect of contaminant and oxygen feed on a catalytic process (Shakor et al., 2022). Several studies on the kinetic models have been carried out to hypothesize different conceptual approaches for describing the catalyst surface mechanism in the catalytic oxidation of VOCs (Hu, 2011; Zou et al., 2019). Power-law (P-L) model is the most facile mathematical kinetic equation used to express the relationship between the reaction rate with the rate constant and reactant concentration or pressure (Tseng and Chu, 2001). Mars-Van Krevelen (MVK) and Langmuir-Hinshelwood (L-H) models are used to express the reaction rate, as well as to elucidate the mechanism of catalytic oxidation of VOCs over metal oxides (Arzamendi et al., 2009). The MVK model usually illustrates the acute and absolute reactions over the metal oxides-derived catalysts (Genty et al., 2019; Vannice, 2007). Experimental data from kinetics of methane in the oxygen-rich mixtures via cobalt oxide (Bahlawane, 2006); the oxidation of VOCs over SmMnO3 perovskites (Liu et al., 2019), and the oxidation of toluene over CoAlCe catalyst (Genty et al., 2019) were all well expressed by the MVK model. L-H model, on the other hand, is used to investigate the adsorption and desorption of gas molecules, which interact with reactants on the catalyst surface (Mahmood et al., 2021). The L-H model is also used to explain the dependence of oxidation rate on reactant concentration in heterogeneous catalytic processes (Dang et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2002). Since the catalytic reaction is a chemical adsorption, L-H model shows more consistent with the catalytic oxidation of styrene by Fe2O3/MnO (Tseng and Chu, 2001) than that of the MVK model. The most challenging data to derive in a catalytic oxidation system is involved kinetic parameters.

The XANES method in XAS (X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy) is often used to specify the oxidation state and association status of materials because of its sensitivity to the elements valence state (Cai et al., 2019). Besides, by using XANES, it is able to distinguish the species of identical standard oxidation stages but distinctive coordination due to its sensitivity to bondings and oxidation states. In this study, XANES was utilized to analyze the difference in metal valence before and after the reaction. Accordingly, the change in the structure before and after the reaction is based on the valence alteration of metal elements (Fe, Mn, and Cu) and the difference in the atomic structure of the second layer from the absorbing atoms. Hence, the intermediate product of the catalyst surface in the catalytic reaction can be determined. Moreover, the EXAFS provides information about the structure and bonding of an excited atom’s local environment, including the identity of distance and the number of adjacent atoms and the disorder grade in a specific atomic shell (Teo and Exafs, 2012). Theoretically, the catalyst does not participate in the reaction, but practically, the structure of the catalyst can be influenced by surface reactions, reactants, and residues. Hence, EXAFS can provide more accurate differences in the structure before and after the catalytic reaction (Zhao et al., 2015).

In this study, we synthesized Mn,Cu co-doped Fe2O3 (hereafter denoted as Mn,Cu-Fe2O3), calcined at 400 °C for toluene oxidation in a continuous fixed-bed reactor. The obtained experimental results provide preliminary data to evaluate the aforementioned kinetic models for the best representative of the complete toluene oxidation reactions over Mn,Cu-Fe2O3 catalyst. Particularly, kinetic models are first built up by considering the nature of oxidation reactions on active sites, then their applicability are justified by comparing the as-simulated model fittings with experimental data. Subsequently, the obtained kinetics and the intrinsic structure characterization of Mn,Cu-Fe2O3 catalyst after reaction is the premise to confirm a catalytic mechanism.

2 Experimental

2.1 Synthesis of catalyst

The iron manganese copper oxide Mn,Cu-Fe2O3 was synthesized by co-precipitation method followed by pyrolysis. Typically, 3 mol Fe(NO3)3, 1 mol Mn(NO3)2, and 1 mol Cu(NO3)2 (Sigma-Aldrich, >99%) were dissolved in a beaker containing 0.5 L of DI water under well mixing, so-called solution A. In another beaker (B), 0.25 mol Na2CO3 (Fluka, USA) was dissolved in 0.5 L of DI water to make another solution (B). The solution in beaker A was gradually added to the solution in beaker B under the well-mixing condition to get a homogeneous solution, which was then kept standstill for 24 h. The precipitation was collected, washed and dried at 105 °C for 12 h. The obtained powder was ground and annealed in air at 400 °C for 4 h. After cooling down, the final product was collected and stored in a closed container.

2.2 Characterization

The change in structural properties of the as-prepared catalyst after oxidation process was investigated via several measurements. The specific atoms of the as-prepared material were detected using X-ray Absorption Near-edge Structure (XANES) measurement. The structure of the region close to central atom was determined by and Extended X-ray Absorption Fine Structure (EXAFS) characterization. Both XANES and EXAFS measurements were performed in National Synchrotron Radiation Research Center, Hsinchu city, Taiwan. All samples were characterized by K-edge XANES and EXAFS in transmission mode under normal conditions using Fe, Mn, and Cu foil as references.

2.3 Catalytic experiments

Catalytic oxidation of toluene over Mn,Cu-Fe2O3 was carried out in a continuous-flow fixed-bed system. The reactor made of glass tube with 9.5 cm long and inner diameter of 2 cm was loaded with 48 g of quartz (1 mm diameter) coated by 0.2 g of catalyst. The gaseous mixture was made up of N2, O2, and toluene in synthetic air by adjusting the flow rate from three sets of these corresponded gas cylinders to have different C7H8 and O2 concentrations. The reactor was wrapped around and heated by a heating tape (300 W). The temperature of reactor was monitored by a thermocouple and controlled in the range of 220–320 °C. The toluene conversion efficiency was measured by a gas chromatograph (GC, PerkinElmer Clarus 500 GC, FID). A blank experiment was implemented without catalyst coated on quartz sands using the same feed stream to assess the effect of temperature on the catalytic activity.

2.4 Optimization of operating parameters for C7H8 conversion

To understand the effect of operating variables on C7H8 oxidation efficiency over Mn,Cu-Fe2O3, the system was proceeded non-isothermally under different initial concentrations of C7H8 and O2, and at different flow rates in the feed stream. The effect of initial concentration of C7H8 was tested by varying C7H8 concentration from 55 to 220 ppmv, while keeping the concentration of oxygen and flow rate (Q) constant (CO2 = 10%, Q = 200 mL min−1). The effect of oxygen concentration in the feed stream was evaluated by maintaining the concentration of C7H8 and flow rate constant (CC7H8 = 165 ppmv, Q = 200 mL min−1), but altering the oxygen concentration of oxygen in the range of 1–30%. The influence of flow rate (from 200 to 500 mL min−1) on the catalytic performance was evaluated at constant O2/C7H8 ratio (104: 165 = 61). O2 was used as an oxidizing agent, and the mass of catalyst in the reactor was maintained stable for all experiments.

The catalytic experiment was conducted at different temperatures (202–307 °C) for testing the mass balance. During the experiment, C7H8 concentration, O2 concentration, and flow rate are adjusted to 165 ppmv, 10%, and 200 mL min−1, respectively. The conversion rate of CO2 was considered as a function of the conversion rate of C7H8. The inlet concentration of C7H8 was controlled, while the outlet concentrations of C7H8 and CO2 were analyzed for mass balance calculation, which is the base to determine experimental reaction rate.

2.5 Kinetic modelling

The catalytic reaction is expressed by the function of conversion rate (Y-axis) versus the temperature (X-axis). Generally, the conversion rate is enhanced with an increase in temperature. In a catalytic reaction dynamic experiment, different concentrations of a reactant results in different reaction rates. Therefore, the reaction rate is discussed according to each catalytic reaction mode using MVK, and L-H models. From the linearity fitting of each temperature, the reaction rate constant (k) is then derived and used for linearity regression to find the activation energy using the Arrhenius equation.

The reaction rate (−r) can be calculated as:

2.5.1 Power-law model

The oxidation rate as a function of toluene and oxygen concentration is described via the Power-law model:

Because CO2 >> Ce, hence CO2 can be assumed to be a constant, the equation can be rewritten as follows:

When concentration of O2 is fixed, the reaction rate of toluene catalytic oxidation is calculated by linear regression fitting. The slope m represents reaction order, whereas rate constant kp can be derived from the intercept ln(kp) at each heating temperature point.

2.5.2 Mars-van Krevelen model

MVK model consists of two steps. The first is the reaction of oxidized catalyst sites (OCS) and toluene to form reduced catalyst sites (RCS). Another is the reaction of RCS and O2 from the gas phase to regenerate OCS for the next cycle. The process can be elucidated by the following reaction equations:

When the combustion reaction of toluene reaches equilibrium, 1 mol of toluene needs 3 mol of oxygen to be completely oxidized (C7H8 + 3O2 → 2CO2 + 2H2O), the reaction rate (r) can be combined into the following formula:

Since CO2 is a constant, ke and kO2 can be derived from the slope of a linear regression fitting (1/(−r) versus 1/Ce) for each temperature point.

2.5.3 Langmuir – Hinshelwood model

In Langmuir Hinshelwood model, it is assumed that all catalyst components have the same activation position, where oxygen and reactant molecules are adsorbed (hereafter denoted by C7H8*, O*, and O2*), then the reactions take place as follows:

Oxygen molecule adsorption and oxygen atom adsorption are explained separately:

-

(1)

Reactions involving the adsorption of molecular oxygen:

-

(2)

Reactions involving the adsorption of atomic oxygen:

When the concentration of toluene is fixed, the Eq. (13) is simplified into two linear equations:

a. Molecular oxygen (O2) adsorption:

A plot of versus CO2 provides a linear regression.

b. Atomic oxygen (O) adsorption:

A plot of versus provides a linear regression.

2.5.4 Activation energy

The activation energy (Ea, kJ mol−1) was calculated using Arrhenius equation:

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Effects of operating parameters

3.1.1 Initial concentration of toluene

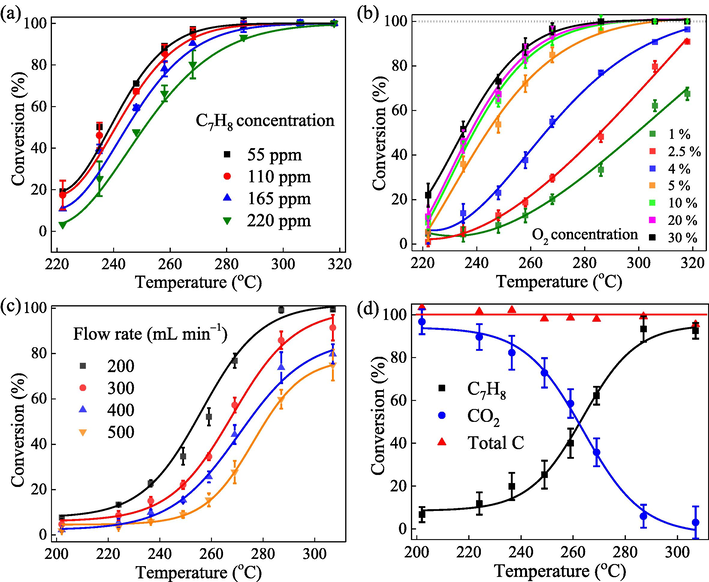

It is well-known that the operating conditions for catalytic oxidation are changeable and complicated. Hence, exploring the effects of working conditions on toluene conversion is essential to get the highest conversion efficiency of the Mn,Cu-Fe2O3 catalyst in practical application. Fig. 1a displays the dependence of conversion rate on the initial concentration of toluene at a constant O2 concentration (10%) and inlet flow rate (200 L min−1). The conversion rate decreases when the concentration of toluene increases from 55 to 220 ppmv. Specifically, when the heating temperature is in the range of 200–270 °C, the conversion rate is inversely proportional to the concentration of feeding toluene, i.e., the higher the concentration of toluene is, the lower the conversion rate will be (Fig. S1a). This result may be due to the limit of the active surface of Mn,Cu-Fe2O3 catalyst for toluene adsorption before oxidation. Because the reactor is a continuous flow, toluene molecules probably compete with each other for the adsorption on Mn,Cu-Fe2O3 catalyst surface. In other words, the more C7H8 molecules enter the reactor, the higher competition for them to occupy on the catalyst surface, resulting in more C7H8 molecules to be kicked out. Hence, it is concluded that the reactant adsorption over the catalyst surface is a rate-determining stage.

(a) and (b) the effect of initial toluene concentration (CO2 = 10%, Q = 200 mL min−1) and inlet O2 concentration (CC7H8 = 165 ppmv, Q = 200 mL min−1) on the conversion rate at different temperatures, respectively; (c) the effect of flow rate on catalytic activity (CO2/CC7H8 ratio = 91); (d) mass balance of C7H8 and CO2 (CC7H8 = 165 ppmv, CO2 = 10%, Q = 200 mL min−1).

It is noteworthy that heating temperature has a supportive effect on the efficiency of C7H8 conversion. Remarkably, at 220 °C, the conversion rate of four investigated C7H8 concentrations is under 20%. However, when the reactor temperature increases to 270 °C, the conversion rate of C7H8 at 55, 110, 165, and 220 ppmv is 97, 95, 90, and 80%, respectively. At 290 °C, C7H8 was removed nearly completely at most concentrations. When the heating temperature reaches 300 °C, C7H8 was converted completely, which promotes the mass transfer process (Wu et al., 2021).

3.1.2 Inlet concentration of O2

In terms of reactants, oxygen concentration also plays an indispensable role in the heterogeneous reaction of catalytic system. As illustrated in Fig. 1b, the conversion rate increases significantly when O2 concentration is in the range of 1–5%, but varies slightly when O2 concentration is in the range of 5–30%. Apparently, reaction rate changes obviously when oxygen concentration is within 5% but keeps constant when oxygen concentration is in the range of 5–30%. This result suggests that to achieve complete C7H8 oxidation, the inlet O2 should be maintained at a concentration greater than 5% (Fig. S1b).

When the O2 concentration increase from 1 to 5%, the probability of oxygen adsorption on the metal oxide surface increases to replenish the oxygen vacancies made by consumed lattice oxygen, resulting in enhancement of C7H8 oxidation (Hu, 2011). Therefore, once oxygen is supplied with a higher concentration, the oxidation will be accelerated. Previous studies also pointed out that metal oxides still can catalyze the oxidation of C7H8 at low concentration or even without oxygen, which is assigned to the effect of lattice oxygen or OH groups on the catalyst surface (Su et al., 2020; Halim et al., 2007). When the supplied O2 concentration is over 5%, the catalytic oxidation of toluene reaches a certain limit and no longer increases, leading to the unchanged performance of toluene oxidation.

The relationship between reaction rate and reactant concentration is shown in Table S1. Typically, the reaction rate increases when the concentration of O2 and C7H8 increases. According to the principle of L-H model, when the C7H8 and O2 are supplied to reactor with low level, increasing the concentration of C7H8 and O2 will also increase the reaction rate. This phenomenon takes place if the adsorption positions of reactants are different, the reaction rate will increase. In contrast, the same adsorption positions may lead to competitive adsorption among reactants, resulting in the reduction of the reaction rate. In terms of the MVK model, increasing O2 concentration improves the reaction rate because more activation sites with oxygen vacancies are supplied on the metal oxide surface for toluene coupling and oxidation (Zhao et al., 2019).

3.1.3 Flow rate

The change in the catalytic reaction efficiency under different flow rates was tested at different temperatures, while the ratio between C7H8 and O2 were kept constant. Fig. 1c shows that the reaction efficiency decreases when the flow rate increases. This result can be assigned to the overload of limited active catalyst surface due to the higher content of toluene in the reactor caused by the higher flow rate. Obviously, the catalytic oxidation of toluene over Mn,Cu-Fe2O3 is the surface-supported reaction. Hence, the limited surface of Mn,Cu-Fe2O3 catalyst cannot accommodate all toluene to be adsorbed on the Mn,Cu-Fe2O3 catalyst surface, resulting in efficiency decrease. Moreover, at the flow rate of 200, 300, 400, and 500 mL min−1, the empty-bed residence time (EBRT), a fraction of catalyst volume (12 cm3) and flow rate (cm3/min), is calculated as 3.6, 2.4, 1.8, and 1.4 s, respectively. Decreasing EBRT from 3.6 s to 2.4 s caused a decrease in toluene removal efficiency by 13.2%, demonstrating that shorter residence time is not favorable for toluene to be adsorbed and decomposed on the Mn,Cu-Fe2O3 catalyst surface, thereby reducing the reaction efficiency (Brandt et al., 2016). In overall, it is concluded that flow rate is conversely proportional to the conversion rate.

3.1.4 Mass balance

In order to determine the catalytic oxidation conversion of toluene over Mn,Cu-Fe2O3 catalyst in the reaction process, the change in concentration of both toluene and CO2 was measured simultaneously through GC/FID. A converting system was used to confirm if other intermediates are generated during the catalytic reaction. As presented in Fig. 1d, toluene is totally converted to CO2 without the generation of any intermediate products. Furthermore, the concentration of C7H8 and CO2 are divided by the total carbon content (summary of C7H8 and CO2) to find the individual conversion rate. Fig. S2 illustrates that the conversion of C7H8 and production of CO2 approximately intersects at 50%, indicating that C7H8 is completely oxidized to CO2. Therefore, the relationship between the reactant (C7H8) and product (CO2) suggests that the possible steps affecting the reaction rate are in the following order: C7H8 adsorption, O2 adsorption, C7H8 oxidation reaction, and product desorption.

3.2 Kinetic modelling

The process to carry out the modeling can be separated into two cases depending on the alteration of C7H8 and O2 concentrations. In the first case, the initial concentration of C7H8 is changed while the concentration of oxygen and flow rate are kept constant, the reaction rate at each investigated temperature point can be obtained using Eq. (1). The results are substituted to Eq. (3) for P-L model, substituted to Eq. (7) to derive reaction orders and reaction rate constants for MVK (ke) models, and substituted to Eq. (13) to get mixed rate constant K′ and K″ for L-H model. Subsequently, by using the Arrhenius equation (Eq. (16)), the activation energy (Ea) can be determined. In the second case, the inlet oxygen concentration is changed while the concentration of toluene and flow rate are kept constant, the reaction rate at investigated temperature points can be obtained using Eq. (1). After that, the results are substituted to Eqs. 17 and 18 to get the reaction rate constants (K1′, K1″) and (K2′, K2″) for L-H models, respectively. From the linear plot of Arrhenius equation, the activation energy can be obtained using the reaction rate constants (K1′, K1″) and (K2′, K2″) against different temperatures (1000/T). The pairs (K1′, K1″) and (K2′, K2″) are used to calculate k, Ke, and KO2 for a reaction involving O2 and O adsorption, respectively. The best fit giving model can be specified based on determination coefficient (R2) and their activation energies.

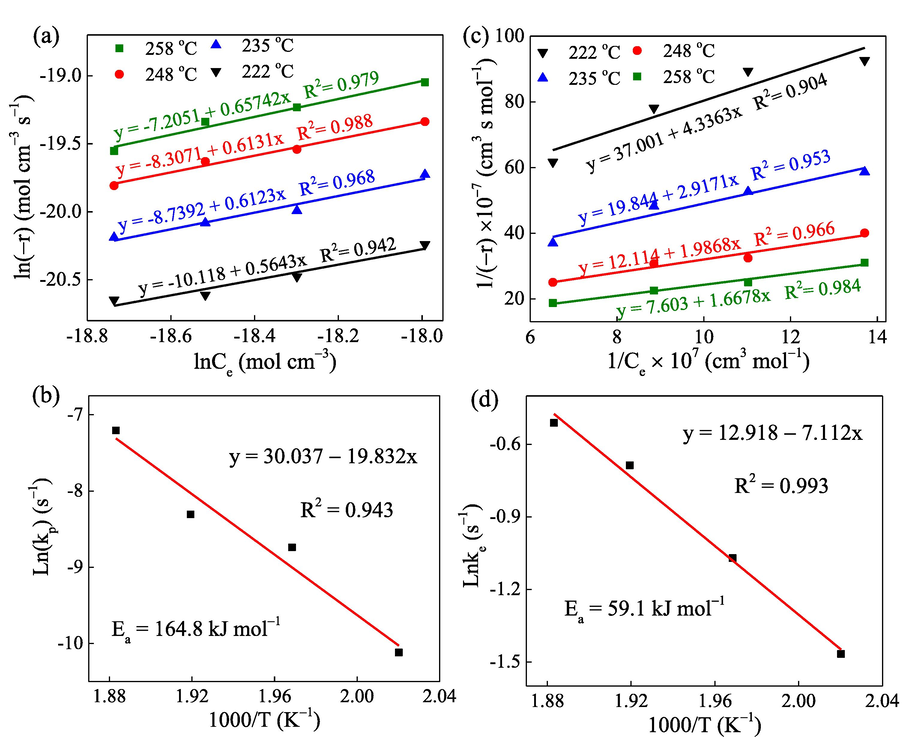

3.2.1 Power-law model

As displayed in Table S2, under constant oxygen concentration (10%), the reaction rate of toluene oxidation over Mn,Cu-Fe2O3 catalyst increases as the reaction temperature increases. The linear regression fittings for the P-L model are shown in Fig. 2a, in which the slope represents the reaction order, whereas the intercepts symbolize the rate constant kp. The Arrhenius fitting graph is exhibited in Fig. 2b with R2 = 0.943. The activation energy is calculated to be 164.8 kJ mol−1, and the frequency factor is 11.1 × 1012 s−1. Since the R2 value is low, the PL model is not suggested to be feasible for the catalytic oxidation of C7H8 over Mn,Cu-Fe2O3 catalyst. In general, the Power-law model mainly assumes a heterogeneous catalytic reaction mode based on homogeneous mode (Pandhare et al., 2018). Therefore, it is less applicable when complex reactions, such as adsorption or multi-molecular reactions, are involved. According to the catalytic reaction data results, the low catalytic reaction is more complicated and may include the mechanism of the reactant or product adsorption.

(a) and (b) linear fitting of C7H8 oxidation for the PL model and corresponded Arrhenius equation, respectively; (c) and (d) linear fitting of C7H8 oxidation for the MVK model and corresponded Arrhenius equation, respectively.

3.2.2 Mars-van Krevelen model

Generally, the mechanism of MVK is explained that the adsorption of one molecule occurs on top of the previous adsorbed one. Specifically, MVK model clarifies a redox reaction cycle of surface lattice oxygen, reactants, and oxygen, focusing on surface redox reactions, i.e., the source of oxygen required for toluene oxidation is lattice oxygen. Fig. 2c illustrates the linearity data fitted by the MVK model at each temperature point. The reaction rate constants derived from the slope for temperature points were then collected and plotted linearity using Arrhenius equation. As shown in Fig. 2d, the results show the R2 value is 0.993 and the activation energy Ea was obtained as 59.1 kJ/mol and frequency factor A of 0.41 × 106 s−1. Based on chemical mechanism, the MVK consists of the two stages occurred in the catalytic reaction between the catalyst and C7H8 (Wang et al., 2018). The first stage is the interaction of C7H8 with the lattice oxygen on the surface of the metal oxide, resulting in the formation of CO2 and H2O, which was proved in mass balance discussion part. The followed stage relates to the supplement of lattice oxygen by adsorbed oxygen in the gas phase for the next cycle of reactions.

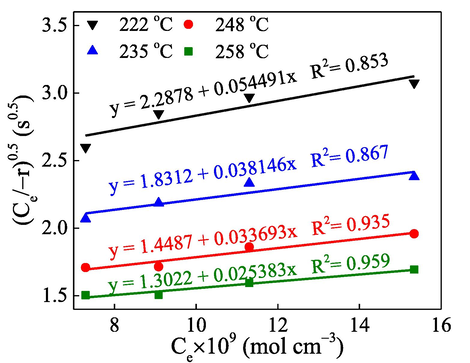

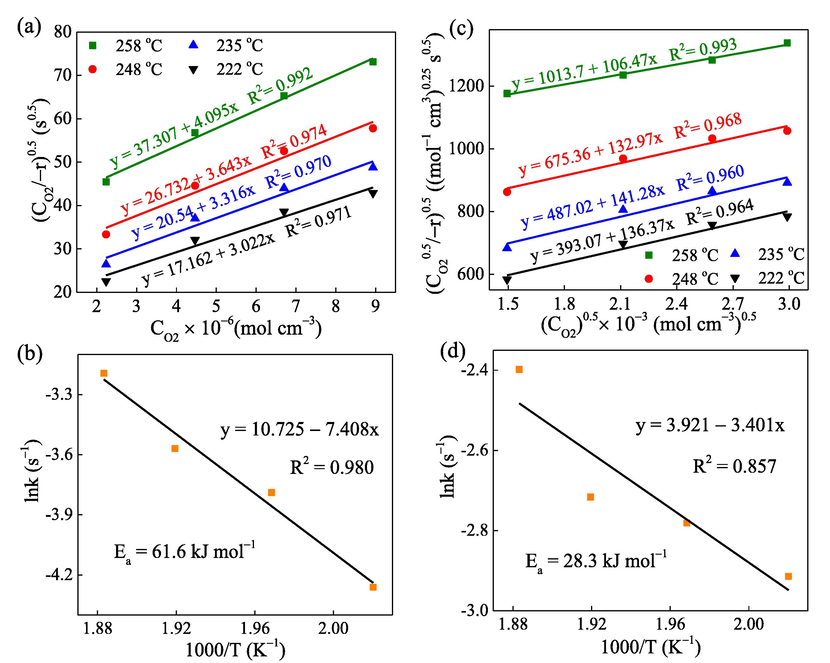

3.2.3 Langmuir Hinshelwood model

From the result of the MVK model, the oxygen concentration is assumed to have no effect on the catalytic reactions; it can therefore be a constant. However, the L-H model shows that the oxygen concentration has a higher correlation with the catalytic reaction rate than the C7H8 concentration. Fig. 3 illustrated the linearity curves with high R2 values fitted by L-H model. The K′ and

values for each line can be derived from the slope and intercept and shown in Table S3. Even though the O2 concentration is greater than C7H8 concentration, its influence on the catalytic oxidation of C7H8 should be put in a deep consideration to get more understanding of the oxidation kinetics and mechanism as well. Typically, the interaction of reactants (toluene) and O2 on the catalyst surface can be described by L-H model. If we assume that C7H8 and O2 adsorb at the same activation position, the progress of the catalytic reaction should then be discussed. In other words, both lattice oxygen and adsorbed oxygen participate in the C7H8 oxidation reaction, which also agrees with previous studies (Tang et al., 2018; Gao et al., 2018). The reaction rate in the case of fixed C7H8 concentration and altered O2 concentration is shown in Table S4.

Linear fitting of C7H8 oxidation for the L-H model.

The result data are then substituted to Eq. (14) and plotted the linear regression at various heating temperatures (Fig. 4a) to show the dependence of reaction rate on the oxygen molecules (O2). Subsequently, K1′ and K1″ at each temperature point can be derived from the intercept and slope of the linear equation (Table S5). When temperature increases, both K1′ and K1″ decrease. The obtained data of K', K“, K1′, and K1″ are combined with the known values of Ce and CO2 to compute the value of k, Ke, KO2 for the O2 adsorption. Fig. 4b exhibits the rate constant k fitted by the Arrhenius plot and the obtained activation energy of 61.6 kJ mol−1, which is within the range for the catalytic reaction (Tseng and Chu, 2001). Previous studies have also proved that the adsorption of oxygen molecules on the catalyst surface is a vital step during the catalytic process of pollutants oxidation (Tseng and Chu, 2001; Chu et al., 2001).

(a) and (b) kinetic linear fitting of C7H8 oxidation in the case of K1′, K1″ by the L-H model and Arrhenius equation, respectively; (c) and (d) kinetic linear fitting of C7H8 oxidation in the case of K2′, K2″ by the L-H model and Arrhenius equation, respectively.

Similarly, by substituting the achieved data to Eq. (15), a linear regression at various heating temperatures can be plotted (Fig. 4c) to show the dependence of reaction rate on the oxygen atoms (O). Herein, K2′ and K2″ at each temperature point can be derived from the intercept and slope of the linear equation (Table S6). The values of K', K“, K2′, and K2″ are combined with the known values of Ce and CO2, the value of k, Ke, KO2 for the reaction involved with O adsorption can also be estimated from their definition. Fig. 4d exhibits the Arrhenius equation fitting of rate constant and activation energy of 28.3 kJ mol−1. In both cases, the plot for calculating K′ and K″ shows that the catalytic reaction has a lower correlation with the adsorption of reactants, while K1′, K1″ and K2′, K2″ plotting show high linearity of the attributable oxygen concentration. Therefore, the L-H model indicates that the main influencing factors of the catalytic reaction have a low correlation with the reactant adsorption but a high correlation with the redox properties of metal oxides. This redox ability may come from the metal itself or be affected by the desorption of the product on the surface.

3.3 The change of chemical compositions and states after catalytic reaction

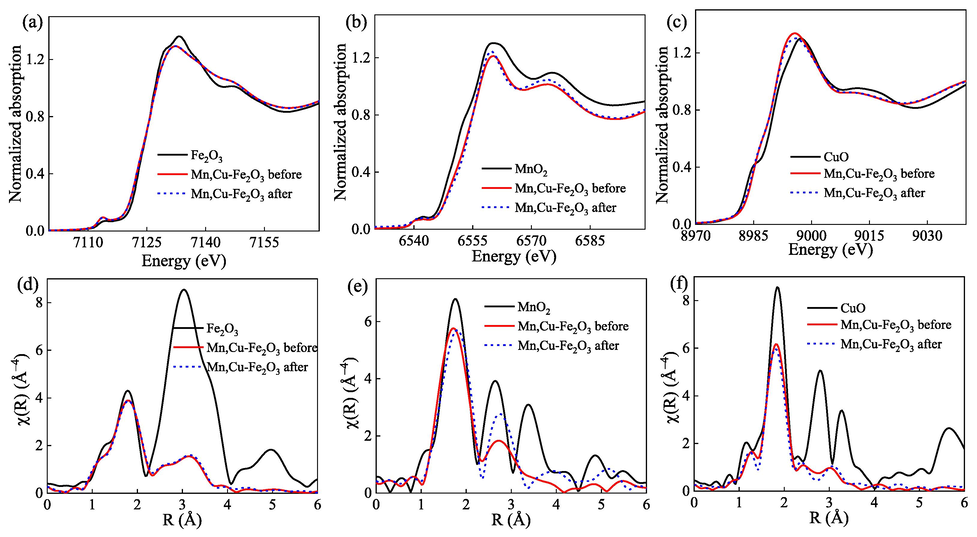

3.3.1 XANES

Fig. 5a shows that there is almost no change in the valence and structure of the spectrum of Fe before and after the reaction. Therefore, it can be inferred that Fe2O3 plays a role as an electron balance, transfer, and structure stability in the catalytic reaction of the toluene oxidation process.

XANES (a, b,c) and EXAFS (d, e, f) of Fe, Mn, and Cu before and after catalytic oxidation, respectively.

In Fig. 5b, the XANES spectrum of Mn reduced slightly, from 14.891 eV before the reaction to 13.996 eV after the reaction (set E0 = 6542 eV), indicating that part of Mn might be reduced from Mn4+ to Mn3+ state (Manceau et al., 2012). This result suggests the establishment of oxygen vacancies to compensate for the charge loss. In Fig. 5c, the spectra of Cu before and after the catalytic reaction are slightly different, indicating that the structure and the valence did not change. Hence, it can be estimated that Cu may also serve as an active center, but the effect is not as good as Mn.

In summary, the XANES results show the reduction of Fe, Mn, and Cu. The activation of Mn4+ was documented to be more active than noble metal oxides and gives better catalytic performance (Wu et al., 2013). It was also reported that a synergistic combination of copper and manganese provides more active sites than individual ones (Aguilera et al., 2011). Einaga et al. demonstrated the incorporation of Cu into Mn oxides can build up the average oxidation state of Mn on the surface sites higher than bulk sites, resulting in higher activity compared to single-metal oxides (Einaga et al., 2014).

3.3.2 EXAFS

As shown in Fig. 5d, there is almost no difference in Fe structure between before and after the reaction. Therefore, it can be determined that Fe may act as an electron balance or transfer or a carrier in the catalytic reaction. The formation of Fe/CuOx composite reduces the phase shift of Mn oxide. In Mn K-edge EXAFS (Fig. 5e), the 1–2 Å Mn-O in the first layer is slightly shifted, and the second layer Mn-O-Mn has more obvious changes, indicating that Mn may be the main reaction activation center of the catalyst (Kou et al., 1998). Hence, it can be concluded that the activation center of Mn could be the formation of a complex structure from Mn3+ and Mn4+. The results show that it may be part of the partial reduction process of Mn4+ to Mn3+. The change in Mn-O-Mn structure of the second layer about 2–3 Å might come from the adsorption of reactants and products on the catalyst surface (Yang et al., 2020). This interference signal is generated by Mn-O-C, which superimposes with the original layer.

Accordingly, Mn-O-Mn will cause the change and compensation of the signal and become significant changes after 3 Å. The results of the EXAFS analysis of Cu in Fig. 5f show a slight change in the structure of the catalyst after the catalytic reaction. Hence, the activation center is formed by co-doping of Mn and Cu the composite structure of Mn3+ and Mn4+, resulting in higher catalytic reaction activity. Therefore, the formation of part of the Mn and Cu structures in Mn,Cu-Fe2O3 can also improve the reactivity. Li et al. have demonstrated the existence of Cu2+/Mn3+ ↔ Cu+/Mn4+ in the reaction system (Li et al., 2021). The authors also stated that in the metal oxide catalyst, the reaction is based on the redox of the metals and the interaction between the lattice O and oxygen. The effect of Cu2+/Mn3+ ↔ Cu+/Mn4+ can reduce the hindrance of the aforementioned reaction, resulting in the improvement of the catalytic efficiency. Besides, the mixed structure of Mn3+ and Mn4+ accelerates the electron transfer and speeds up the catalytic reaction. Therefore, the formation of Mn/Cu structure in Mn,Cu-Fe2O3 composite can also improve the reactivity.

3.4 Catalytic reaction mechanism

The reaction mechanism of gas catalytic oxidation is examined and demonstrated by the hypothetical computation and analysis of the reaction kinetic models. The calculation results of the activation energy of each catalytic reaction are shown in Table S7. The P-L model represents a relationship between two quantities, in which one changes as a power other. Therefore, it is only applied for heterogeneous reactions in high-temperature condition. In this case, the calculated Ea is 164.8 kJ mol−1, which is the highest compared to other models. Meanwhile, the MVK model mainly discusses the redox cycle between the C7H8 and the lattice oxygen of the metal oxide surface in the catalytic reaction, forming oxygen vacancies. This theory matches the calculated Ea (59.1 kJ mol−1). In contrast, based on the kinetic data that both oxygen species participate in the oxidation reaction, the L-H model demonstrates that oxygen concentration has a high correlation with the reaction rate, i.e., the reaction is also supported by O or O2 binding of metal oxides on the catalyst surface. Therefore, the L-H model is appropriate for the catalytic reaction involving molecular (Ea = 61.6 kJ mol−1) and atomic oxygen adsorption (Ea = 28.3 kJ mol−1). The Ea values calculated by MVK and O2 adsorption-related L-H models are almost the same, which indicates that both models correspond to the participation of adsorbed oxygen on the catalyst surface. Therefore, it can be concluded that the calculation results in MVK and L-H models consolidate the reactions proposed in Eqs. (4), 5, 8, 9, and 10. The lowest Ea obtained in the case of the O adsorption-related L-H model demonstrates that atomic oxygen is easy to be adsorbed on the catalyst surface and then triggers the oxidation reaction to happen faster, compared to molecular oxygen. In summary, the MVK model can be the most workable for the description of toluene catalytic oxidation over Mn,Cu-Fe2O3 composite, whereas the L-H model could be feasible to describe the kinetics of oxygen adsorption and oxygen-involved reaction mechanism.

Moreover, characterization analysis after the catalytic test confirms that the change of Mn,Cu-Fe2O3 during the catalytic oxidation of toluene is related to the reduction of Mn,Cu-Fe2O3 catalyst. Based on the results of XAS (XANES and EXAFS) analysis, combined with kinetic models, it can be inferred that the reaction process is as follows:

At lower energy, C7H8 is first partially oxidized to form an intermediate product of Mn,Cu-Fe2O3—CO. Some of the electrons are transferred to Mn4+ to reduce Mn4+ to form Mn3+. After breaking the Mn,Cu-Fe2O3 from Mn,Cu-Fe2O3—CO, the —CO bond is completely oxidized to form CO2 and desorbed from the surface. Fe2+/Mn3+/Cu+ reacts with oxygen and is then oxidized to Mn4+, forming a catalytic reaction cycle.

4 Conclusion

A new approach to the linearity of the kinetic models for evaluating the reaction mechanism versus experimental data of toluene catalytic oxidation in a continuous-flow reactor was developed based on the consideration of reactant fluctuation. The conversion rate of toluene oxidation over Mn,Cu-Fe2O3 is proportional to C7H8 and O2 concentration and temperature. However, the toluene conversion rate is disproportional to the flow rate due to the limit of active sites on the catalyst surface and correlative reaction between C7H8 and O2. The enhancement of C7H8 adsorption on the Mn,Cu-Fe2O3 catalyst surface with high redox property induces the complete oxidation of C7H8 to CO2. As a result, the initial concentrations of toluene of 165 ppmv and oxygen of 10% at a flow rate of 200 mL min−1 give the highest catalytic performance of Mn,Cu-Fe2O3. The Mars-van Krevelen model fitting data indicate the majority of the toluene catalytic oxidation process regards the interaction between C7H8 and lattice oxygen on the surface of Mn,Cu-Fe2O3. Furthermore, L-H model fitting demonstrates that adsorbed oxygen species also participated in the catalytic reactions. The surface reaction mechanism of toluene oxidation over Mn,Cu-Fe2O3 catalyst was proposed through the newly developed kinetic models and surface characterization (XANES and EXAFS) of the catalyst after the reaction. Overall, the importance of our findings is the applicability of kinetic models and characterization to the direct identification of catalytic reaction mechanism of gas removal process over metal oxides-based catalysts in continuous flow catalytic systems.

Acknowledgements

Author acknowledges the CONEX-Plus programme funded by Universidad Carlos III de Madrid (UC3M) and the European Commission through the Marie-Sklodowska Curie COFUND Action (Grant Agreement No 801538). The authors extend their sincere appreciation to the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSPD2023R682), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia for the support.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Cu–Mn and Co–Mn catalysts synthesized from hydrotalcites and their use in the oxidation of VOCs. Appl. Catal. B-Environ.. 2011;104:144-150.

- [Google Scholar]

- Kinetics and selectivity of methyl-ethyl-ketone combustion in air over alumina-supported PdOx–MnOx catalysts. J. Catal.. 2009;261:50-59.

- [Google Scholar]

- Kinetics of methane combustion over CVD-made cobalt oxide catalysts. Appl. Catal. B-Environ.. 2006;67:168-176.

- [Google Scholar]

- The use of novel packing material for improving methane oxidation in biofilters. J. Environ. Manage.. 2016;182:412-420.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chapter 1 - Introduction. In: Wang X., Chen X., eds. Novel Nanomaterials for Biomedical, Environmental and Energy Applications. Elsevier; 2019. p. :1-36.

- [Google Scholar]

- The kinetics of catalytic incineration of dimethyl sulfide and dimethyl disulfide over an MnO/Fe2O3 catalyst. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc.. 2001;51:574-581.

- [Google Scholar]

- Indirect Z-scheme nitrogen-doped carbon dot decorated Bi2MoO6/g-C3N4 photocatalyst for enhanced visible-light-driven degradation of ciprofloxacin. Chem. Eng. J. 2021;422:130103

- [Google Scholar]

- Catalytic properties of copper–manganese mixed oxides prepared by coprecipitation using tetramethylammonium hydroxide. Catal. Sci. Technol.. 2014;4:3713-3722.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cerium–copper–manganese oxides synthesized via solution combustion synthesis (SCS) for total oxidation of VOCs. Catal. Lett.. 2020;150:1821-1840.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ru/MnXCe1OY catalysts with enhanced oxygen mobility and strong metal-support interaction: exceptional performances in 5-hydroxymethylfurfural base-free aerobic oxidation. J. Catal.. 2018;368:53-68.

- [Google Scholar]

- Investigation of reaction mechanism and kinetic modelling for the toluene total oxidation in presence of CoAlCe catalyst. Catal. Today. 2019;333:28-35.

- [Google Scholar]

- Factors affecting CO oxidation over nanosized Fe2O3. Mater. Res. Bull.. 2007;42:731-741.

- [Google Scholar]

- A review on catalytic methane combustion at low temperatures: Catalysts, mechanisms, reaction conditions and reactor designs. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev.. 2020;119:109589

- [Google Scholar]

- Catalytic combustion kinetics of acetone and toluene over Cu0.13Ce0.87Oy catalyst. Chem. Eng. J.. 2011;168:1185-1192.

- [Google Scholar]

- Amorphous features of working catalysts: XAFS and XPS characterization of Mn/Na2WO4/SiO2 as used for the oxidative coupling of methane. J. Catal.. 1998;173:399-408.

- [Google Scholar]

- Efficient defect engineering in Co-Mn binary oxides for low-temperature propane oxidation. Appl. Catal. B-Environ.. 2021;282:119512

- [Google Scholar]

- Insight into the catalytic performance and reaction routes for toluene total oxidation over facilely prepared Mn-Cu bimetallic oxide catalysts. Appl. Surf. Sci.. 2021;550:149179

- [Google Scholar]

- Atomically dispersed Ti-O clusters anchored on NH2-UiO-66(Zr) as efficient and deactivation-resistant photocatalyst for abatement of gaseous toluene under visible light. J. Colloid Interface Sci.. 2023;635:323-335.

- [Google Scholar]

- Catalytic oxidation of VOCs over SmMnO3 perovskites: catalyst synthesis, change mechanism of active species, and degradation path of toluene. Inorg. Chem.. 2019;58:14275-14283.

- [Google Scholar]

- Degradation behavior of mixed and isolated aromatic ring containing VOCs: Langmuir-Hinshelwood kinetics, photodegradation, in-situ FTIR and DFT studies. J. Environ. Chem. Eng.. 2021;9:105069

- [Google Scholar]

- Determination of Mn valence states in mixed-valent manganates by XANES spectroscopy. Am. Mineral.. 2012;97:816-827.

- [Google Scholar]

- Computational kinetic study on atmospheric oxidation reaction mechanism of 1-fluoro-2-methoxypropane with OH and ClO radicals. J. King Saud Univ. Sci.. 2020;32:587-594.

- [Google Scholar]

- Development of kinetic model for hydrogenolysis of glycerol over Cu/MgO catalyst in a slurry reactor. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res.. 2018;57:101-110.

- [Google Scholar]

- A detailed reaction kinetic model of light naphtha isomerization on Pt/zeolite catalyst. J. King Saud Univ. - Eng. Sci.. 2022;34:303-308.

- [Google Scholar]

- Roles of oxygen vacancies in the bulk and surface of CeO2 for toluene catalytic combustion. Environ. Sci. Technol.. 2020;54:12684-12692.

- [Google Scholar]

- Enhanced lattice oxygen reactivity over Fe2O3/Al2O3 redox catalyst for chemical-looping dry (CO2) reforming of CH4: Synergistic La-Ce effect. J. Catal.. 2018;368:38-52.

- [Google Scholar]

- EXAFS: Basic Principles and Data Analysis. Springer Science & Business Media; 2012.

- The kinetics of catalytic incineration of styrene over a MnO/Fe2O3 catalyst. Sci. Total Environ.. 2001;275:83-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- An analysis of the Mars–van Krevelen rate expression. Catal. Today. 2007;123:18-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- The kinetics of catalytic incineration of (CH3)2S2 over the CuO–MoO3/γ-Al2O3 catalyst. J. Environ. Sci. Health A. 2002;37:1649-1663.

- [Google Scholar]

- Roles of oxygen vacancy and Ox− in oxidation reactions over CeO2 and Ag/CeO2 nanorod model catalysts. J. Catal.. 2018;368:365-378.

- [Google Scholar]

- A novel redox-precipitation method for the preparation of α-MnO2 with a high surface Mn4+ concentration and its activity toward complete catalytic oxidation of o-xylene. Catal. Today. 2013;201:32-39.

- [Google Scholar]

- Kinetic study of highly efficient CO2 fixation into propylene carbonate using a continuous-flow reactor. Chem. Eng. Process.: Process Intensif.. 2021;159:108235

- [Google Scholar]

- Photocatalytic degradation of air pollutant by modified nano titanium oxide (TiO2)in a fluidized bed photoreactor: Optimizing and kinetic modeling. Chemosphere. 2023;319:137995

- [Google Scholar]

- Single Mn atom anchored on N-doped porous carbon as highly efficient Fenton-like catalyst for the degradation of organic contaminants. Appl. Catal. B-Environ.. 2020;279:119363

- [Google Scholar]

- A review of recent advances in catalytic combustion of VOCs on perovskite-type catalysts. J. Saudi Chem. Soc.. 2019;23:645-654.

- [Google Scholar]

- Indoor occurrence and health risk of formaldehyde, toluene, xylene and total volatile organic compounds derived from an extensive monitoring campaign in Harbin, a megacity of China. Chemosphere. 2020;250:126324

- [Google Scholar]

- EXAFS characterization of palladium-on-gold catalysts before and after glycerol oxidation. Top. Catal.. 2015;58:302-313.

- [Google Scholar]

- The activation of oxygen through oxygen vacancies in BiOCl/PPy to inhibit toxic intermediates and enhance the activity of photocatalytic nitric oxide removal. Nanoscale. 2019;11:6360-6367.

- [Google Scholar]

- Integrated adsorption and photocatalytic degradation of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) using carbon-based nanocomposites: a critical review. Chemosphere. 2019;218:845-859.

- [Google Scholar]

Appendix A

Supplementary material

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2023.102812.

Appendix A

Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article: