Translate this page into:

Isolation and molecular characterization of novel Streptomyces sp. ACT2 from marine mangrove sediments with antidermatophytic potentials

⁎Corresponding author at: China – US (Henan) Hormel Cancer Institute, Zhengzhou, People’s Republic of China. moses10c@gmail.com (M. Fredimoses)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

The present work accomplished with the aim of examination of anti-dermatophytic efficiency of Streptomyces isolates against dermatophytic fungi from mangrove estuary area of Tamil Nadu. Five hundred and six actinomycete isolates were retrieved from the sediment soil samples in Manakudi mangrove estuary, south west coast of Tamil Nadu, India. Among 506, 138 isolated were identified and categorized based on their structural similarity and cultural conditions. Selected actinomycete strains were screened for anti-dermatopytic fungal activity by cross streak and agar well diffusion methods. The cultural, biochemical and molecular features of the 10 antagonistic isolates were belongs to Streptomyces species (60%) and other non-Streptomyces (40%) Among, Streptomyces sp. ACT2 strains exhibited significant activity against selected dermatophytes. The most promising Streptomyces sp. ACT2 (GQ478247) was identified and analyzed further of their bioactive compounds. The anti-dermatophytic compounds were identified as bahamaolides and polyenepolyol from the active fraction ADF4 by GC–MS analysis.

Keywords

Mangrove

Antidermatophytic fungal activity

Streptomyces

GC–MS

1 Introduction

Dermatomycoses, a kind of external fungal infection for human beings are provoked by dermatophytic fungus. It is a group of filamentous fungi attacking and accruing nutrients from the skin, hair and nails, which is composed by keratin tissues (White et al., 2014; Kim et al., 2016). Dermatophytoses are spread worldwide particularly with more prevalent in tropical and sub-tropical countries because of the hot and humid environment which favours their growth (Janardhan and Vani, 2017). In general, the dermatophytic fungus was categorized into three genera viz., Trichophyton, Microsporum and Epidermophyton (Coulibaly et al., 2016). The association of dermatophytic infection may extent from slight to severe as an effect of the hosts’ immune systems by fungus metabolic products. Remarkably India is a largest sub-continent with diverse geography, located within the world tropical and subtropical belts. Hence, this climatic condition is favorable to the procurement and supporting the fungal infections in India (Chakrabarti et al., 2008; Ghannoum and Isham, 2009).

The frequency of antimicrobial resistance amongst fungal pathogens is keep increasing and also frightening the entire world (Lestari et al., 2012; Cowen et al., 2014). Antifungal medicines such as imidazole are presently used to treat the dermatophytic fungal infections, even-though it causes detrimental side effects and/or also develops resistance (Vandeputte et al., 2012). As a result, new antifungal compounds desirably existing with unique mode of action and without side effects are required to expand the treatment of dermatophytic fungal infections (Spadari et al., 2013). The compound antimycin (non-polyenic) antifungal compound was isolated from S. albidoflavus AS25 (Nafis et al., 2018).

Actinomycetes are Gram-positive bacteria with high G + C content in the genome and dominant in marine mangrove sediments (Gong et al., 2018). It produces a series of bioactive metabolites, many of which possessed antibacterial, antifungal and antitumor properties (Raghava Rao et al., 2012; Kavitha and Vijayalakshmi, 2013). Since, over 60% of naturally occurring antibiotics are recovered from actinomycetes (Zotchev, 2012). Among, streptomycetes are well known as antibiotic producers and represent about 75–80% of important commercially available antibiotic producer (Singh et al., 2012). They are reviewed highly valuable, as they produce countless chemical compounds including antibiotics, enzymes, vitamins, growth hormones, antitumor agents and other pharmaceutically effective compounds with varied biological activities (Gharaibeh et al., 2003). Study of such kind of economically viable actinomycetes more particularly Streptomyces could offer an insight into the formulation of new antifungal antibiotics to the support of human health by overwhelming the complications created by the drug resistant pathogenic fungus. Hence, the present works were explored to screening and isolation of effective antidermatophytic fungal bioactive compounds from actinomycetes associated with marine mangrove sediment.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Sampling site and collections

The sediment soil samples were collected from different mangrove sites at different depths from Manakudy estuary (8°088′N, 77°486′E) located in Kanyakumar district, Tamil Nadu, India for the period of one year. The samples were composed with Vanveen grab sampler (Ravikumar et al., 2011) and it was collected with sterile plastic containers from the field and were transferred to the laboratory with proper labeling and stored prior to studies.

2.2 Isolation and characterization of actinomycetes

The soil sediment samples were processed according to method described by Singh et al. (2016). One gram of sediment samples was serially diluted with 5 ml of sterilized sea water (dilution 2 × 10−1), mixing and further diluting 1:10 with sterilized sea water (dilutions 2 × 10−4). The dilution procedure was repeated in triplicate for each sample. One ml of each sample was inoculated by spreading over the surface of starch casein nitrate (SCN) agar plates added with Nalidixic acid (20 µg/ml), Nystatin (25 µg/ml) and Cycloheximide (50 µg/ml) to minimize the other microbial contaminations respectively. All media were prepared by using 50% of sea water and distilled water. The plates were incubated at 28 °C for 5 days.

2.3 Screening of actinomycete isolates for antidermatophytic fungal activity

The pure cultures of actinomycetes were screened for antidermatophytic fungal activity by cross streaking and well diffusion method described by CLSI (2004). SCN agar plates were prepared and inoculated with pure culture of actinomycetes and incubated at 28 °C for 7 days. After adequate growth of the isolates, the test fungal pathogens viz., Trichophyton rubrum, Trichophyton mentagrophytes, Epidermophyton floccosum, and Microsporum canis were inoculated at perpendicular to the actinomycetes streak and incubated for 3 days at 28 °C. After 3 days of inhibition zone was measured. Fluconazole as positive and DMSO as negative control were used for evaluation.

2.4 Characterization of actinomycetes

2.4.1 Cultural and biochemical characters

The medium used for morphological studies was SCN and ISP2 (yeast extract malt extract agar) (Shirling and Gottlieb, 1966) and the incubation time of pure cultures were 3–5 days at 28 °C. Morphological characterizes were observed by microscopy techniques. Cultural and biochemical characteristics of strain ACT2 were studied as per the methods described by Holt et al. (1994) and Williams et al. (1989).

2.4.2 Molecular characters

The DNA was isolated with standard protocol described by Hopwood (1985) and 16S rRNA gene were amplified by PCR with forward primer- F243 (5′GGATGAGCCCGCGGCCTA-3′) and reverse primer R513 GC (5′-CGGCCGCGGCTGCTGGCACGTA- 3′). The PCR reaction mixture consists of 50 ng of DNA, PCR buffer, 1.5 Mm MgCl2, 10 Mm deoxynucleoside triphosphate mixture, 50 pmol of each primer, and 0.5 U of ExTaq polymerase. The PCR reaction conditions consisted of an initial denaturation at 94 °C for 5 mins; 30 cycles at 94 °C for 1 min, annealing 63 °C for 1 min and 72 °C for 1 min; and final 5 mins extension at 72 °C. The amplified 16S rRNA product were observed by DNA gel electrophoresis and purified by using a QIA quick PCR clean up kit (Qiagen Inc., USA). The clarified gene products were sequenced and the evolutionary tree was generated using neighbor-joining method (Saitou and Nei, 1987) and using MEGA X (Kumar et al., 2018).

2.5 Fermentation of antagonistic isolate ACT2

The pure culture of Streptomyces sp. ACT2 was inoculated in to 100 ml Erlenmeyer flasks containing 25 ml of starch yeast peptone (SYP) broth. For large scale fermentations, 25 ml of the seed culture were transferred to a 1000 ml Erlenmeyer flask contained 500 ml of SYP medium. The flasks were incubated for 7 days at 28 °C. The total 5 L volumes of fermented broth were collected for separation of antifungal compounds.

2.6 Extraction and purification of bioactive metabolites

The filtered fermented broth (pH 7.2) was adjusted to pH 5.0 using 1 N HCl. The equal volume of ethyl acetate was used for complete extraction of compound. The upper solvent phase was concentrated with rotary vacuum evaporator at 50 °C room temperature. This vacuum evaporator extraction process was repeated for three times to obtain complete extraction of active principles and then the crude extracts were used for further purification. 3.8 g of crude extract was subjected to purification by silica gel column chromatography (22 × 5 cm, Silica gel 60, Merck). Chloroform and methanol were used as an eluting solvent. Total twelve fractions were collected i.e., ADF1-ADF12 and further evaluated for their antidermatophytic fungal activities. The active fraction of ADF4 was further analyzed by GC–MS.

2.7 Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) determination of fraction ADF4

The MIC for active fraction ADF4 was determined by standard broth micro-dilution method (24). Muller Hinton Broth (MHB) was prepared and autoclaved at 121 °C for 15 min. In the 96 well micro-titer plate first 0.1 ml broth was added and then different concentrations of ADF4 i.e., 500 μg/ml, 250 μg/ml, 125 μg/ml, 62.5 μg/ml, 31.25 μg/ml, 15.62 μg/ml and 7.81 μg/ml were added to their respective wells. Three ml of fungal culture (1 × 105 PFU/ml) was transferred into the corresponding wells. The micro-titer plate was incubated for 2 days at 28 °C. DMSO and fluconazole were included as a negative and positive control respectively. Later five ml of the test broth was inoculated on Muller Hinton Agar (MHA) plates to observe the sustainability of the fungus. MIC was determined at a low concentration of the ADF4 fraction needed to complete growth inhibition of fungus. The experiments were done in triplicate (Duraipandiyan et al., 2009).

2.8 GC–MS analysis

The partially refined ADF4 fraction was examined by GC–MS in Indian Institute of Technology (IIT), Chennai. GC–MS system equipped with a fused silica capillary column (CW- amine 60 × 0.25 mm I.D., Film thickness 0.5 μm) was used to analyze the compounds from the active fraction. The total GC–MS conditions were programmed described by Roy et al. (2006). The peaks of the fraction in gas chromatography were analyzed with mass spectroscopy. The spectrum was evaluated with NIST library data (Version 2.0).

3 Results

3.1 Isolation of actinomycetes

Manakudy mangrove ecosystem is one of the artificially regenerated mangroves in south west cost of Tamil Nadu, India. Which is 8 years old, exploration of microbial diversity in the Manakudy mangroves ecosystem are not attempted so far. Hence, the present study has been undertaken to isolates Actinomycetes and their antifungal properties against dermatophytes. The sediment soil samples from different depths at various sites were collected monthly for a period of one year and all the samples were subjected to actinomycetes isolation. The isolated actinomycetes in AIM (Actinomycetes Isolation Medium) were showed different colony morphology. After three days of incubation period, the plates with chalky white spots colonies were selected and extended for two more days and it were showed slight difference in morphology with variation in aerial mycelia colour with white, pale pink, grey, yellow, orange, brown and black.

3.2 Screening actinomycete isolates for anti-dermatopytic fungal activity

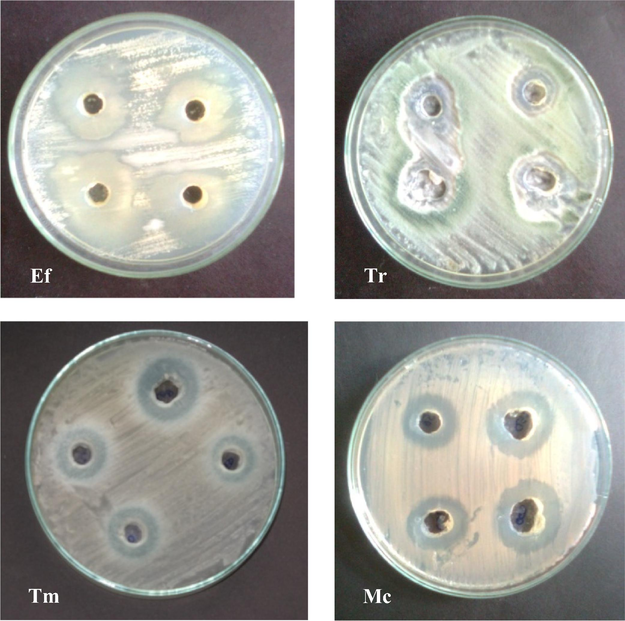

About 506 actinomycetes strains were obtained from various sites of marine mangrove sediments in our previous studies (Ravikumar et al., 2011). 138 morphologically different actinomycetes were screened for antidermatophytic fungal activity by cross streak assay. Out of 138 isolates, most effective 10 isolates were selected for further screening and fermentation process. The ethyl acetate crude extract was collected after 10 days of incubation and it was used for antidermatophytic activity. All the 10 isolates were exhibited significant antidermatophytic activities against four tested dermatophytes such as T. rubrum, T. mentagrophytes, E. floccosum, M. canis. The isolate ACT2 exhibited maximum antifungal activity than the other actinomycete isolates (Table 1). Among 10, ACT2 isolate was observed to be most prominent isolate and showed maximum zone of inhibition (23 mm) against E. floccosum in comparison with standard fluconazole (30 µg/well) zone of inhibition (35 mm), followed by 19 mm (T. mentagrophytes), 16 mm (T. rubrum) and 14 mm (M. canis) (Fig. 1). (–); no zone of inhibition. @all data are the average of three replicates. * Fluconazole as a positive control. # DMSO as a negative control.

Tested dermatophytic fungal pathogens

Actinomycete isolates/Zone of inhibition (mm)@

ACT1

ACT2

ACT3

ACT 4

ACT 5

ACT 6

ACT 7

ACT 8

ACT 9

ACT 10

Fl* (30 µg)

Epidermophyton floccosum

12.00±0.4

23.00 ± 0.4

14.00 ± 0.4

-

–

11.00 ± 0.4

–

–

10.00 ± 0.4

–

35.00 ± 0.8

Trichophyton rubrum

–

16.00 ± 0.4

12.00 ± 0.4

13.00 ± 0.4

–

–

13.00 ± 0.4

15.00 ± 0.4

12.00 ± 0.4

14.00 ± 0.4

21.00 ± 0.4

Trichophyton mentagrophytes

13.00 ± 0.4

19.00 ± 0.4

–

11.00 ± 0.4

12.00 ± 0.4

12.00 ± 0.4

14.00 ± 0.4

13.00 ± 0.4

–

13.00 ± 0.4

30.00 ± 1.2

Microsporum canis

–

14.00 ± 0.4

12.00 ± 0.4

10.00 ± 0.4

13.00 ± 0.4

–

–

10.00 ± 0.4

12.00 ± 0.4

–

18.00 ± 0.5

Antifungal activities of actinomycete isolate ACT2 against dermatophytic fungal pathogens (Ef - Epidermophyton floccosum; Tr - Trichophyton rubrum; Tm - Trichophyton mentagrophytes; Mc - Microsporum canis).

3.3 Characterization of efficacious isolate ACT2

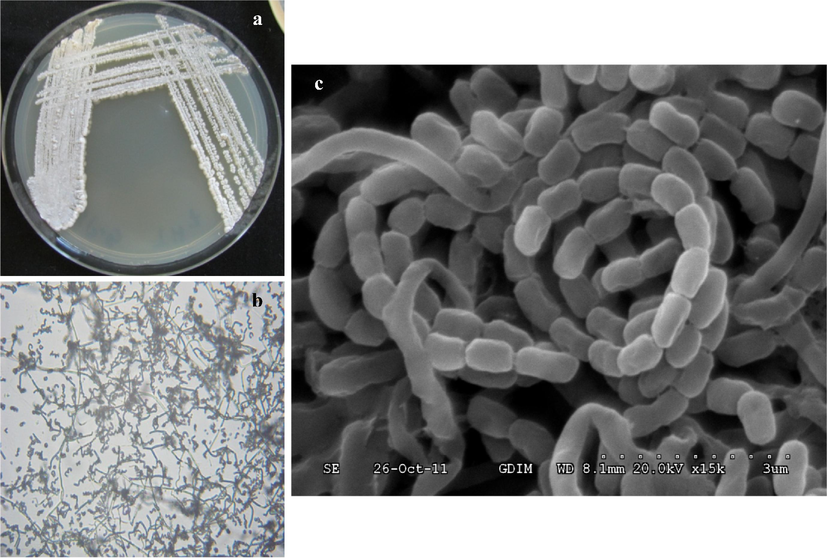

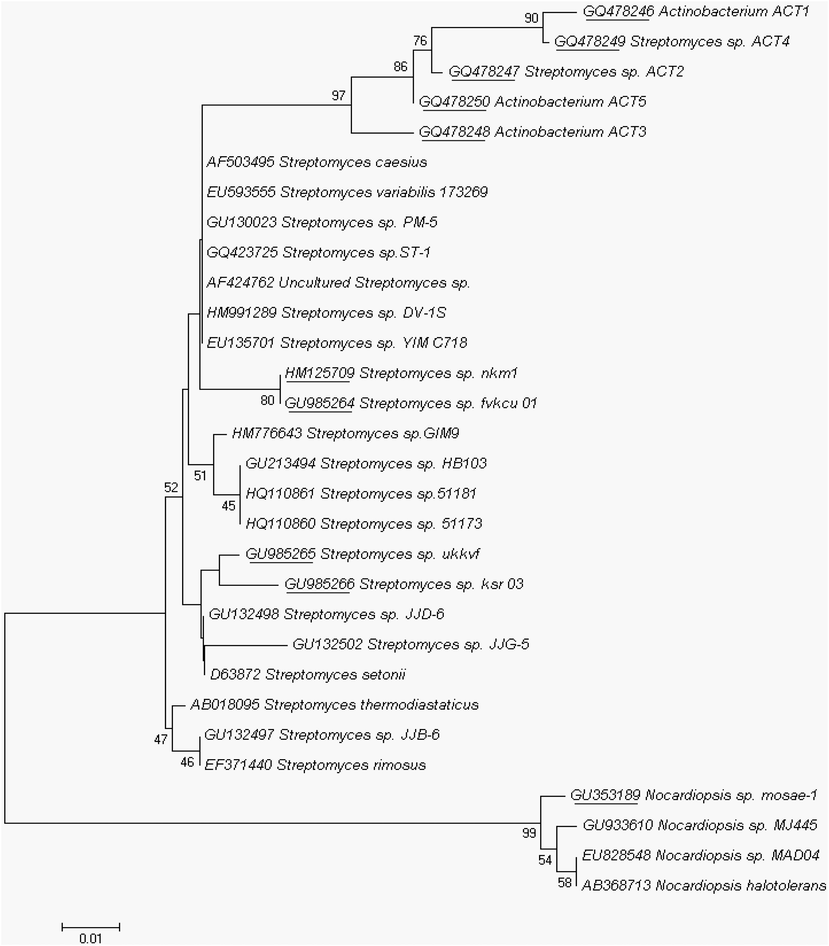

The external and biochemical features of isolate ACT2 were depicted in Table 2 and Fig. 2. The genomic DNA were extracted from the selected actinomycetes and followed by PCR amplification of gene 16S rRNA. The resulted sequences were aligned with BLAST analysis through GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Phylogenetic analysis of the isolated actinomycetes was revealed that 6 isolates out of ten are the members of the genus belongs to Streptomyces, which was dominant actinomycetes genus of the marine mangrove sediments (Fig. 3). Three isolates were either member of uncultured Actinobaterium and Nocardiopsis, with the closest 16S rDNA gene sequence similarity of 98% uncultured Actinobacterium and 100% similarity with Streptomyces sp. and its accession number were showed in the Table 3. +: presence; −: absence.

Characteristics

ACT2

Gram reaction

Positive

Mycelium

Aerial mycelium

Color of the mycelium

White

Production of diffusible pigment

−

Range of temperature for growth

26 °C–30 °C

Optimum temperature for growth

28 °C

Range of pH for growth

5.0–7.5

Optimum pH for growth

7.0

Protease Hydrolysis

−

Strach Hydrolysis

+

Lipase Hydrolysis

+

Gelatinase Hydrolysis

−

Utilization of Sugars

L-Arabinose

−

Fructose

+

Galactose

+

D-Mannitol

+

Rhamnose

−

Sucrose

+

Xylose

−

Cellulose

−

Glucose

+

(a) Colony morphology of isolate ACT2 on SCN agar; (b) Microscopic observation of isolate ACT2 mycelium and spores (100×); (c) Scanning electron micrograph of Streptomyces sp. ACT2 spore grown on SCN agar at 28 °C for 10 days.

The evolutionary history was inferred using the Neighbor-Joining method. The percentage of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (1000 replicates) was shown next to the branches (frequencies below 40% disregarded). The GenBank accession number together with the culture collection number for each isolate was listed; the accession numbers were underlined, which are our isolates.

Isolates No.

Name of the isolates

Accession number

Identity (%)

Act1

Actinobacterium sp.ACT1

GQ478246

98

Act2

Streptomyces sp. ACT2

GQ478247

100

Act3

Actinobacterium sp. ACT3

GQ478248

98

Act4

Streptomyces sp. ACT4

GQ478249

100

Act5

Actinobacterium sp. ACT5

GQ478250

98

Act6

Streptomyces sp. fvkcu01

GU985264

100

Act7

Streptomyces sp. ukkvf

GU985265

100

Act8

Streptomyces sp. ksr03

GU985266

100

Act9

Streptomyces sp. nkm1

HM125709

100

Act10

Nocardiopsis sp. mosae1

GU353189

98

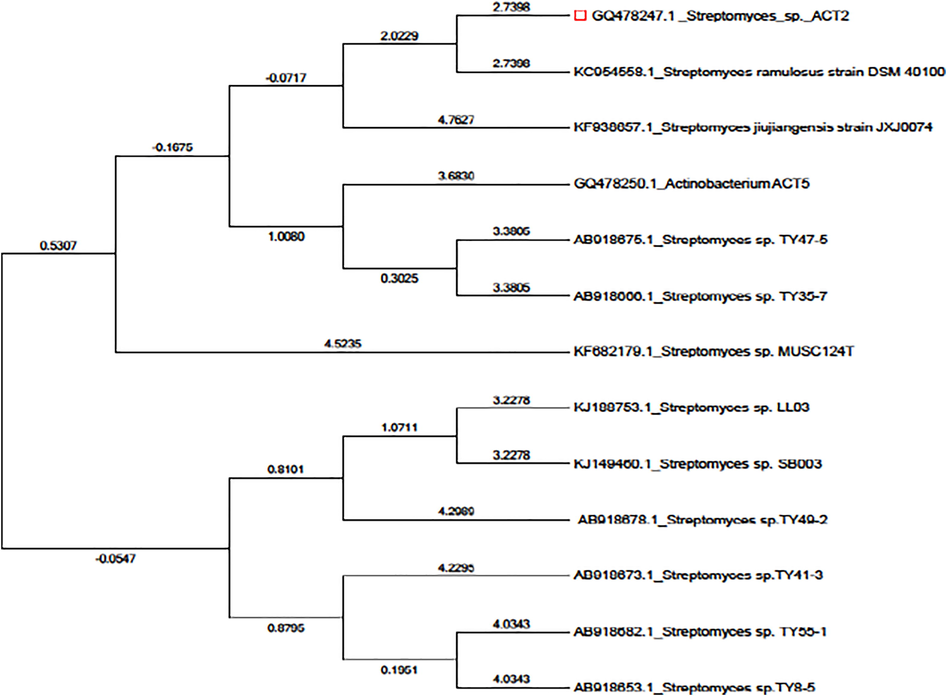

The partially sequenced ACT2 isolate was deposited in GenBank with accession number GQ478247 and it consists of 266 bp in length. Phylogenetic relationships were constructed with the alignment and cladistics analysis of homologous nucleotide sequence of known 12 Streptomyces sp. The approximate phylogenetic position of the isolate ACT2 is displayed in Fig. 4. According to the 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis, ACT2 was found similar to S. ramulosus strain DSM 40,100 (KC954558) (homology 100%) and identified our isolate belongs to Streptomyces sp.

Phylogenetic tree showing relationships between the representatives isolate ACT2 and other marker strains belonging to Streptomyces sp. clad based on its 16S rDNA gene sequence by neighbor-joining method.

3.4 MIC determination of fraction ADF4

MIC was determined only with active fraction of ADF4. Fraction ADF4 displayed MIC values of 15.62 μg/ml against E. floccosum, 62.5 μg/ml against T. rubrum and M. canis and 31.25 μg/ml against T. mentagrophytes. Whereas MIC values of standard fluconazole were also determined and low concentration was observed in E. floccosum (15.0 μg/ml), followed by T. mentagrophytes (20.0 μg/ml) and 25.0 μg/ml for T. rubrum and M. canis (Table 4).

Tested fungal dermatophytes

MIC (µg/ml)

AF 4

Fluconazole

Epidermophyton floccosum

>15.625

15

Trichophyton rubrum

>62.5

25

Trichophyton mentagrophytes

>31.25

20

Microsporum canis

>62.5

25

3.5 Purification and GC–MS analysis

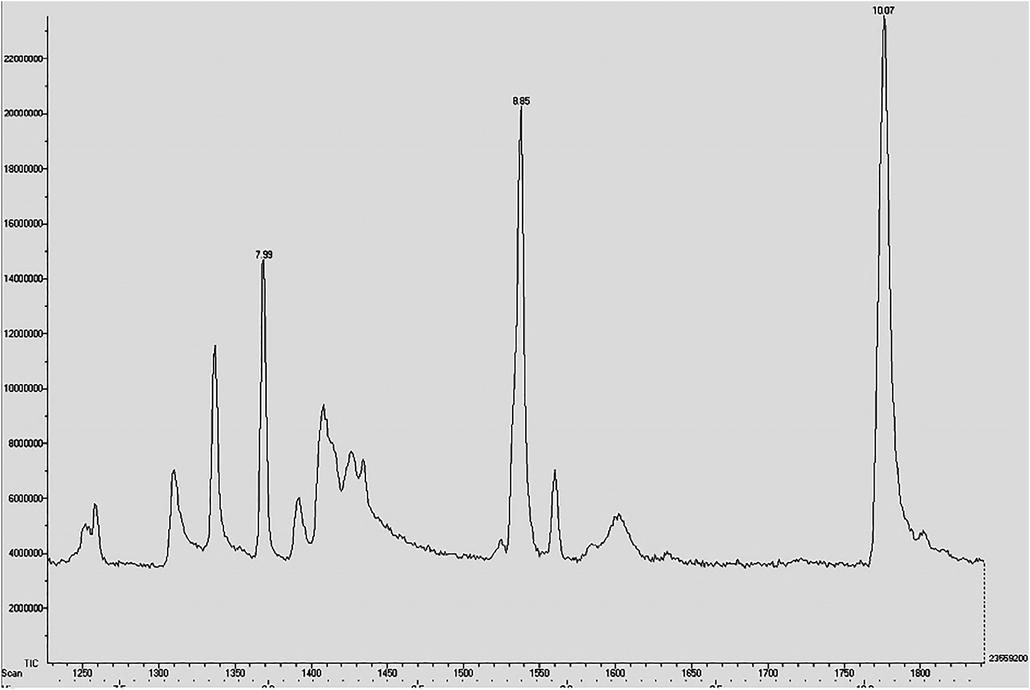

The twelve fractions (ADF1 to ADF12) were obtained through column chromatography purification process with silica gel and eluting solvent composed of chloroform and methanol CHCl3/MeOH in linear gradient (90:10, 80:20, 70:30, 60:40, 0:100). The significant inhibitory activity was observed for ADF4 fraction and partially purified ADF4 fraction was further analyzed by GC–MS. Two peaks were observed with retention time of 7.99 and 8.85 min respectively. Compared with available NIST library and above peaks were showed as bahamaolides (7.99) and polyene polyol macrolides (8.85) respectively and both compounds were antifungal compounds as per earlier literature (Fig. 5).

GC–MS spectrum of partially purified ethyl acetate extracts of isolate ACT2 and the peaks indicate active antifungal metabolic compounds.

4 Discussion

Marine environment and ecology has been confirmed that remarkable and fascinating expedient for inventing new and potent bioactive compounds producing organisms. Among, actinomycete includes 10% of the total colonizing in marine collections. There have been forty new bioactive microbial metabolites from marine organisms in the late 1990 (Bernan et al., 1997) to present years, and near 50 percent of them be found in actinomycetes (Kasanah and Triyanto, 2019; Subramani and Sipkema, 2019). It clearly demonstrated that the hit rate of new antibiotics from marine actinomycetes was higher than the other microorganisms.

In our screening of actinomycetes from Manakudy marine mangrove sediments, which are exhibiting potential antidermatophytic fungal activities, the culture colony morphology of our isolates were related to that earlier work reported by Sengupta et al. (2015) it evidently shows that it’s belonged to the genus Streptomyces. The marine actinomycetes were sources of new antibacterial compounds viz., marinomycin, abyssomicin, marinopyrrole, and lipoxazolidinone. The marine actinomycetes based antifungal metabolites are very lower than antibacterial compounds. Although, the antifungal compounds such as polyketides, spiroketals, reveromycins, bafilomycin derivatives, were recently isolated from marine Streptomyces strains (Aiab et al., 2014). Our present investigations were revealed Streptomyces sp. ACT2 produce antifungal compounds such as bahamaolides (7.99) and polyenepolyol macrolides (8.85) were analyzed by GC–MS. This research study, showed prospective antifungal principal compounds were found in Streptomyces sp. ACT2 isolated from Manakudy marine sediments.

5 Conclusions

The present work presented that, antifungal bioactive compounds from Streptomycetes sp. ACT2 fermentation broth exhibited significant inhibition activity against dermatophytic fungi such as E. floccosum, T. mentagrophytes, T. rubrum and M. canis. The GC–MS analysis results revealed two antifungal compounds i.e., bahamaolides and polyenepolyol were owned in the active fraction of the strains ACT2. The Manakudy marine mangrove sediments of Kanyakumari, south west coast of India, consists utmost biodiversity of actinomycetes and possess biological active compounds more specifically against with fungal pathogens.

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to the Researchers Supporting Project Number (RSP-2019/36) King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The corresponding author would like to thank for K.S.Rangasamy College of Arts and Science for faculty and other assistance for completion of this project.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Axinelline A, a new COX-2 inhibitor from Streptomyces axinellae SCSIO02208. Nat. Prod. Res.. 2014;28:1219-1224.

- [Google Scholar]

- Marine microorganisms as a source of new natural products. Adv. Appl. Microbiol.. 1997;43:57-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Overview of opportunistic fungal infections in India. Jpn. J. Med. Mycol.. 2008;49:165-172.

- [Google Scholar]

- CLSI, 2004. Method for Antifungal Disk Diffusion Susceptibility Testing of Yeasts, Approved Guideline. CLSI document M44-A. CLSI, 940 West Valley Road, Suite 1400, Wayne, Pennsylvania 19087-1898, USA.

- Dermatophytosis among Schoolchildren in three Eco-climatic Zones of Mali. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis.. 2016;10:e0004675

- [Google Scholar]

- Mechanisms of antifungal drug resistance. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med.. 2014;5:a019752

- [Google Scholar]

- Ghannoum, M.A., Isham, N.C., 2009, Clinical Mycology. 2nd ed. Dermatophytes and dermatophytoses; pp. 375–384.

- Antibacterial and antifungal activity of Flindersine isolated from the traditional medicinal plant, Toddalia asiatica (L.) Lam. J. Ethnopharmacol.. 2009;123:494-498.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of combined 16S rDNA and strb1 gene targeted PCR to identify and detect streptomycin-producing Streptomyces. J. Basic Microbiol.. 2003;43:301-311.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antibacterial and antitumor potential of actinomycetes isolated from Mangrove Soil in the Maowei Sea of the Southern Coast of China. Iran J. Pharm. Res.. 2018;17:1339-1346.

- [Google Scholar]

- Holt, J.G., Krieg, N.R., Sneath, P.H.A., Staley, J.T., Williams, S.T., 1994. Bergey's Manual of Determinative Bacteriology, 9th Ed. Baltimore, MD; Philadelphia; Hong Kong; London; Munch; Sydney; Tokyo: William and Wilkins.

- Hopwood, D.A., 1985. Genetic manipulation of Streptomyces. A laboratory manual.

- Clinico-mycological study of dermatophytosis. Int. J. Res. Med. Sci.. 2017;5:31-39.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bioactivities of halometabolites from marine actinobacteria. Biomolecules. 2019;9:225.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of bioactive compounds produced by Nocardia levis MK-VL113 & Streptomyces tendae TK-VL333 for cytotoxic activity. Indian J. Med. Res.. 2013;137:391-393.

- [Google Scholar]

- Dermatophyte abscesses caused by Trichophyton rubrum in a patient without pre-existing superficial dermatophytosis: a case report. BMC Infect. Dis.. 2016;16:298.

- [Google Scholar]

- MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across Computing Platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol.. 2018;35(6):1547-1549.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial resistance among pathogenic bacteria in Southeast Asia. Southeast Asian. J. Trop. Med. Public Health. 2012;43:385-422.

- [Google Scholar]

- Screening for Non-polyenic Antifungal Produced by Actinobacteria from Moroccan Habitats: assessment of Antimycin A19 Production by Streptomyces albidoflavus AS25. Int. J. Mol. Cell Med.. 2018;7:133-145.

- [Google Scholar]

- Isolation and characterization of antagonistic actinobacteria from mangrove soil. J. Biochem. Tech.. 2012;3:361-365.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biodiversity of actinomycetes in manakkudi mangrove ecosystem, South West Coast of Tamilnadu. Ann. Biol. Res.. 2011;2:76-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- Dibutyl phthalate, the bioactive compound produced by Streptomyces albidoflavus 321.2. Microbiol. Res.. 2006;161:121-126.

- [Google Scholar]

- The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol.. 1987;4:406-425.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial activities of actinomycetes isolated from unexplored regions of Sundarbans mangrove ecosystem. BMC Microbiol.. 2015;15:170.

- [Google Scholar]

- Methods of characterization of Steptomyces sp. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol.. 1966;16:313-340.

- [Google Scholar]

- Isolation, Screening, and Identification of Novel Isolates of Actinomycetes from India for Antimicrobial Applications. Front. Microbiol.. 2016;7:1921.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antifungal antibiotic production by Streptomyces sp. isolated from soil. Int. J. Curr. Res. Rev.. 2012;4:7-16.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antifungal activity of actinobacteria against fungus isolates of clinical importance. R. Bras. Bioci. Porto. Alegre.. 2013;11:439-443.

- [Google Scholar]

- Marine rare actinomycetes: a promising source of structurally diverse and unique novel natural products. Mar. Drugs. 2019;17:249.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antifungal resistance and new strategies to control fungal infections. Int. J. Microbiol. 2012:26.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fungi on the skin: dermatophytes and Malassezia. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med.. 2014;4:a019802

- [Google Scholar]

- Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology. In: Williams S.T., Sharpe M.E., Holt J.G., eds. Genus Streptomyces Waksman and Henrici 1943, 339AL. Baltimore, MD: Williams and Wilkins; 1989. p. :2452-2492.

- [Google Scholar]

- Marine actinomycetes as an emerging resource for the drug development pipelines. J. Biotechnol.. 2012;158:168-175.

- [Google Scholar]