Translate this page into:

HPTLC estimation and anticancer potential of Aloe perryi petroleum ether extract (APPeE): A mechanistic study on human breast cancer cells (MDA-MB-231)

⁎Corresponding authors at: Chair for DNA Research, Zoology Department, College of Science, King Saud University, P.O. Box 2455, Riyadh 11451, Saudi Arabia. nidachem@gmail.com (Nida Nayyar Farshori), maqsoodahmads@gmail.com (Maqsood Ahmed Siddiqui)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Abstract

Objectives

Aloe perryi plant in the genus Aloe (family: Asphodelaceae), have been used in traditional medicine systems. Herein, we aimed to analyze the anticancer effects of A. perryi petroleum ether extract (APPeE) against human breast cancer (MDA-MB-231) and normal (HEK-293) cell lines. Further the biomarker stigmasterol, isolated from A. perryi extract was quantified by a densitometric high-performance thin layer chromatography (HPTLC) method.

Methods

The cytotoxic potential of APPeE was measured by MTT assay, neutral red uptake (NRU) assay, and morphological identification.

Results

APPeE-induced a concentration dependent strong cytotoxic effects on MDA-MB-231 cells with an IC50 value of 24.5 μg/ml in contrast to HEK-293 (IC50 value of > 100 μg/ml). Similar results were obtained by NRU assay. Further cytotoxic concentrations of APPeE increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and activated caspase-3 and −9, leading to apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 cells. Additionally, a significant augment in the expression of p53, Bax, caspase-3 and −9 with a decline in Bcl-2 gene expression confirmed the involvement of apoptosis pathway in MDA-MB-231 cell death. In HPTLC analysis, the solvent system hexane: ethylacetate (8:2 v/v) furnished a sharp peak for stigmasterol (Rf = 0.19 ± 0.001). The low value of % relative standard deviation (RSD) (0.97–1.39) proposed the method is robust. The limit of detection (LOD) and limit of quantification (LOQ) were established as 13.82 and 41.89 ng, respectively. The stigmasterol in APPeE was quantified as 0.238% w/w of dried APPeE.

Conclusions

Hence, this study concludes the promising anticancer effect of APPeE, which might be endorsed to the existence of known anticancer biomarker stigmasterol.

Keywords

Aloe perryi

Anticancer activity

Cytotoxicity

ROS generation

Caspase activity

Apoptosis

1 Introduction

Cancer is the second leading cause of mortality following cardiovascular diseases, and has been globally documented as a key community health dilemma (Xiaomei and Herbert, 2006). Altogether, breast cancer (BC) is recognized as the most common cancer detected in female and is the second most cause of death (GLOBOCAN, 2018). On the basis of BC occurrences and forecast of population, the yearly global BC cases will increase nearly 3.2 million by 2050 (Hortobagyi et al., 2005). Through previous time, cancer treatment has revealed countless developments at operational and theoretical stage with novel advance medicines and vastly effective procedures. But available treatments cause undesirable side-effects and are less effective to some patient, therefore searching alternative and therapeutic novel anticancer agents with less toxicity and high efficacy is need of the day. For thousands of years, herbal medicines have been used as primary source of medical treatment in old remedy system. Because they are originated from nature, herbal medicines have gained a strong attention in the discovery of new phytochemical anticancer agents. Plants are favorite for this purpose because of their abundant availability, environment friendly, economical, and non-toxic nature (Jaffri and Ahmad, 2018a; Jaffri and Ahmad, 2019). Different parts of the plants such as fruits, seeds, and leaves have been utilized intensively for pharmacological purposes (Jaffri and Ahmad, 2018b; Ahmad and Jaffri, 2018; Jaffri and Ahmad, 2018c; Shaheen et al., 2021; Zahra et al., 2021). The medicinal plants signify one of the major progressions of effective agents with anticancer and antiproliferative activities (Makrane et al., 2018). A number of plant extracts have been shown to possess anticancer properties (Wang et al., 2019). Aloe genus plants (Aloe L.), belonging to Asphodelaceae family are dispersed in old world (Klopper and Smith, 2007). The Aloe plants are commonly recognized for their medicinal and health care properties (Salehi et al., 2018). Numerous Aloe plant extracts and their constituents have also been shown to possess anticancer activities (Harlev et al., 2012; Candoken et al., 2017). Aloe perryi (species of genus Aloe), known as Socotrine aloe, is endemic to Socotra Yemen island. The pharmacological and beneficial properties such as antioxidant, antibacterial, and antimicrobial of extracts of A. perryi have been reported (Mothana et al., 2009; Ali et al., 2001). The cytotoxic potential of A. perryi have also been reported against human lung (A-427), urinary bladder (5637), and breast (MCF-7) cancer cells (Mothana et al., 2009). The antiproliferative activities of A. perryi extracts against hepatocellular (HepG2), colon (HT-116), breast (MCF-7), lung (A-549), epithelial (HEp-2), cervical (HeLa), and prostate (PC-3) cancer cells have also been reported by us (Al-Oqail et al., 2016). Among the all tested extracts, petroleum ether extract has shown highest cytotoxic activity. Our literature survey revealed that mechanism of cytotoxic activities and the anticancer phytoconstituent of A. perryi plant has not been extensively studied. Therefore, the aim of this investigation was to examine the mechanisms of APPeE-induced cell death in MDA-MB-231 and normal human embryonic (HEK-293) cell lines. Further a robust validated HPTLC method for quantification of biomarker stigmasterol isolated from APPeE was developed.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Extraction and isolation

Air dried A. perryi flowers (250 g) were crushed and extracted with petroleum ether by cold maceration method at room temperature. The obtained petroleum extract was named as APPeE (14 g). The APPeE was diluted in dimethyl sulfoxide for bioassays. A part of APPeE was subjected to column chromatography over silica gel 60 using chloroform: methanol gradients to obtain 10 subfractions (Fr1 - Fr10). Subfraction Fr5 was re-chromatographed (CHCl3: MeOH) and the fraction eluted at 3% methanol yielded about 25 mg compound 1 upon direct crystallization. The APPeE was stored at 4 °C until use.

2.2 Cell viability assays (MTT and NRU assay)

The MDA-MB-231 and HEK-293 cell lines obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA), were cultured in a CO2 incubator (5% CO2, 95% air, high humidity) at 37 °C. The cell viability was determined following standard protocol for MTT assay (Mosmann, 1983) and NRU assay (Borenfreund and Puerner, 1985). The MDA-MB-231 and HEK-293 cells were treated with various APPeE concentrations (0–100 μg/ml) for 24 h. The cytotoxic effects of APPeE on cell viability of MDA-MB-231 and HEK-293 was calculated as: absorbance of treated group divided by absorbance of control group then multiplying the ratio by 100 to obtained the percent cell viability.

2.3 Cell morphological assay

Cell morphological identification of cytotoxicity induced by APPeE in MDA-MB-231 and HEK-293 was analyzed under optical microscope at 20× magnification. For this assay, cells treated with APPeE at 0–100 μg/ml for 24 h, were observed under inverted contrast microscope.

2.4 ROS generation

Intercellular ROS generation was measured using fluorogenic probe 2′,7′-dichloroflourescen diacetate (DCFH-DA) (Al-Oqail et al., 2019). MDA-MB-231 cells were platted in 48-well plate in the number of 2 × 104 cells/well. The cells exposed to 0, 10, 25, and 50 μg/ml of APPeE for 24 h, were incubated with 20 μM of DCF-DA dye for 60 min. After washing, the quantitative fluorometric detection of DCF was measured using fluorescent microplate reader. The qualitative fluorescence was also observed under inverted fluorescent microscope (Olympus, CKX41, Japan).

2.5 Caspase-3 and -9 activity

Caspase-3 and -9 activity was determined using commercially available colorimetric assay kits (Bio-Vison, USA). Briefly, after respective exposure, cells were lysed and assay reagent 50 μL was added. Then, further incubated in dark for 2 h at 37 °C. The absorbance was read at 400 nm. Compared to control, the results are expressed as fold change in caspase-3 and −9 activities.

2.6 Apoptosis gene expression by quantitative real time PCR (qPCR)

Using commercially available RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, USA), RNA was extracted from untreated and 25 μg/ml of APPeE treated MDA-MB-231 cells for 24 h. About 50% cells were inhibited at 25 μg/ml of APPeE, therefore this concentration was used for apoptosis gene expression study. The quality of the RNA was checked by gel electrophoresis and total RNA was measured using Nano Drop (Bio Rad). Total RNA (1 μg) was then reversed transcribed into cDNA using M−MLV and oligo (dT) primers (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). qPCR analysis was preformed to analyze the relative changes in apoptosis marker genes (p53, caspase-3 and -9, Bax, Bcl-2) using LightCycler® 480 (Roche Diagnostic, Switzerland) (Al-Oqail et al., 2017).

2.7 HPTLC instrumentation and chromatographic conditions

The HPTLC analysis was done on 10 × 10 cm glass backed silica gel 60 F254 HPTLC plates. Automatic TLC Sampler 4 (ATS4) (CAMAG) fitted with a Hamilton Gastight Syringe (25 µL; 1700 Series) was used to apply the samples and standard on the HPTLC plate and the application rate was 160 nL/s. The plate was developed in previously saturated (For 20 min at 22 °C with mobile phase vapour) automatic developing chamber-2 (ADC-2) in linear ascending mode with n-hexane: ethyl acetate (8:2, v/v) as mobile phases. Camag TLC scanner IV was used to scan the developed and derivatized (p-anisaldehyde) plates in the visible range at 540 nm wavelength in absorbance mode by using the deuterium lamp. The slit dimensions were 4.00 × 0.45 mm and the scanning speed was 20 mm/s.

2.7.1 Preparation of standard stock solution

Stock solution of stigmasterol (1 mg/ml) was made by dissolving 1 mg of it in 1 ml methanol. Again, 1 ml of the stock solution was taken and 9 ml methanol was added to it to make the final concentration of standard 100 µg/ml. HPTLC method development, validation, and assay of stigmasterol has been provided in the Supplementary file.

2.8 Statistical analysis

Student’s t-test was employed to analyze the significant differences between control and treated group. Data were expressed as mean ± S.D. and the difference were statistically significant at p < 0.05 compared to control.

3 Results

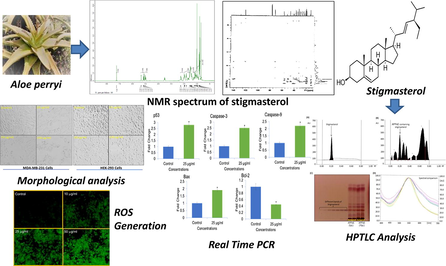

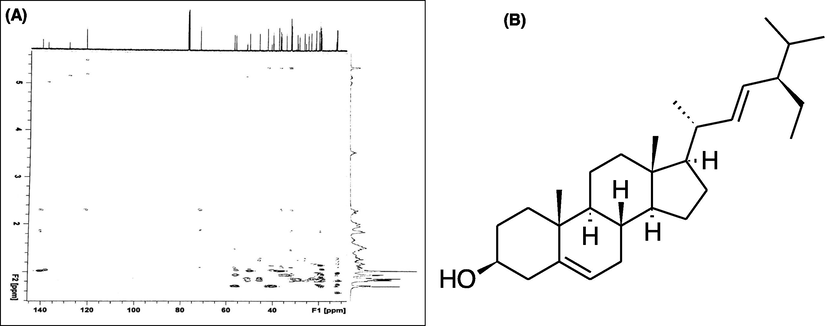

3.1 Identification of isolated compound

The structure of isolated compound was elucidated by its spectroscopic study (1H NMR, 13C NMR, 2D-NMR) (Figs. 1 and 2). Further the structure was confirmed by comparing the data with literature (Kasahara et al., 1994).![(A) 1H NMR spectrum of stigmasterol [400 MHz, CDCl3]; (B)13C NMR spectrum of stigmasterol [125 MHz, CDCl3].](/content/185/2022/34/4/img/10.1016_j.jksus.2022.101968-fig2.png)

(A) 1H NMR spectrum of stigmasterol [400 MHz, CDCl3]; (B)13C NMR spectrum of stigmasterol [125 MHz, CDCl3].

(A) 2D-NMR spectrum of stigmasterol; (B) Chemical structure of compound isolated from A. perryi.

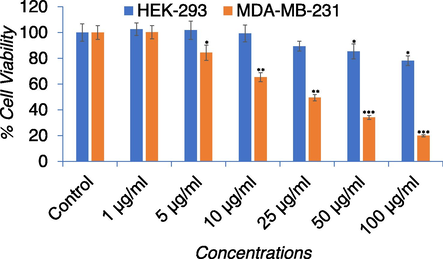

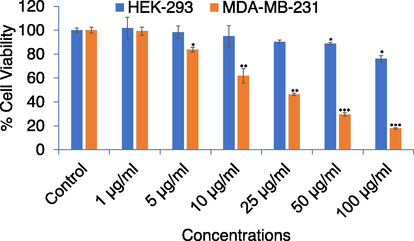

3.2 Cell viability assays (MTT and NRU assay)

As shown in Fig. 3, compared to the control APPeE significantly decreased cell viability of MDA-MB-231 cells in a concentration-dependent way, while APPeE have shown less cytotoxic effect on HEK-293 cells. The NRU assay also exhibited a concentration dependent decrease in MDA-MB-231 cell viability (Fig. 4). The MTT and NRU assays clearly indicated that APPeE revealed higher cytotoxicity on MDA-MB-231 than the normal HEK-293 cells (Figs. 3 and 4).

Percent cell viability by MTT assay in MDA-MB-231 and HEK-293 cell lines. Cells were exposed to varying concentrations (0–100 μg/ml) for 24 h. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 vs control for both cell lines.

Percent cell viability by NRU assay in MDA-MB-231 and HEK-293 cell lines. Cells were exposed to varying concentrations (0–100 μg/ml) for 24 h. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 vs control for both cell lines.

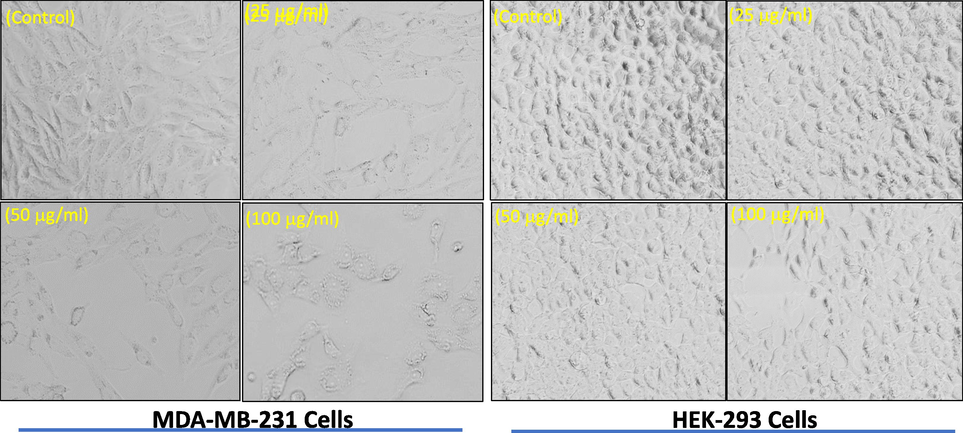

3.3 Cell morphological assay

Treatment of MDA-MB-231 cells with the increasing concentrations of APPeE caused morphological changes as observed by a decline in the number of cells, detachment, rounded shape, and hammering of anchor properties in comparison to regular shape in control (Fig. 5). Whereas, no pronounce effects was seen in the regular morphology of HEK-293 cells exposed to APPeE.

Morphological study of apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 and HEK-293 cells induced by APPeE. Images were acquired by phase contrast light microscopy (Olympus, CKX41, Japan).

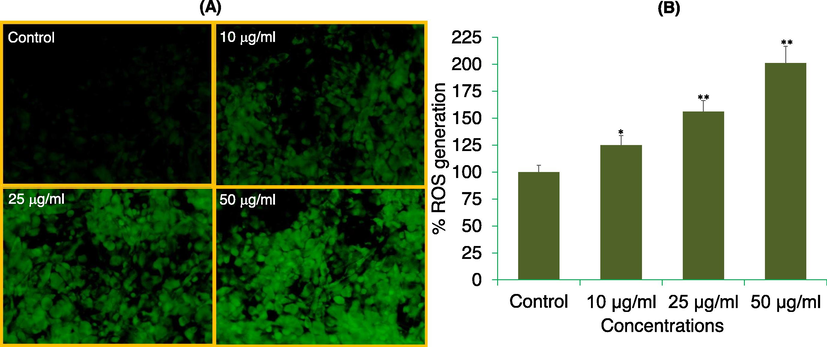

3.4 ROS generation

The production of ROS in APPeE exposed MDA-MB-231 cells at 0, 10, 25 and 50 μg/ml are shown in Fig. 6. As shown in Fig. 6A, in contrast to control, APPeE treatment resulted in a concentration dependent increase in ROS as observed under florescence microscope. As compared to control, an enhance of 25%, 56% and 101% in ROS was observed at 10, 25 and 50 μg/ml of APPeE, respectively after quantitative measurement (Fig. 6B).

ROS generation analysis by DCF-DA dye in MDA-MB-231 cells. (A) Fluorescence of DCF dye in cells treated with 10, 25, and 50 μg/ml of APPeE for 24 h. (B) The graph is illustrating the percent induction in the ROS as compare to control group. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 vs control.

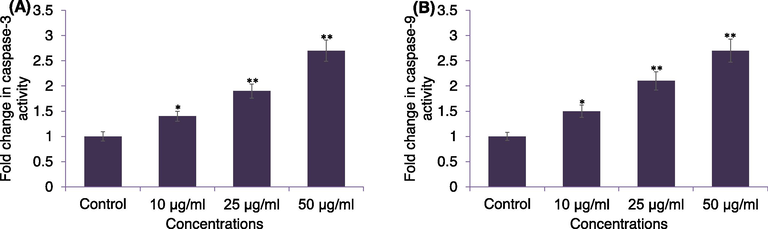

3.5 Caspase-3 and -9 assays

The results of caspase-3 and -9 activity in response to APPeE is shown in Fig. 7. The caspase-3 and −9 was activated significantly (*p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01) by APPeE in a dose dependent manner. The MDA-MB-231 cells exposed to APPeE at 10, 25 and 50 μg/ml was found to increase by 1.4, 1.9- and 2.4-fold in caspase-3 and 1.5-, 2.1- and 2.7-fold in caspase-9 activities as compared to untreated control.

Caspase-3 (A) and casapse-9 (B) enzyme activities in MDA-MB-231 cells exposed to APPeE. Cells were exposed to 10–50 μg/ml of APPeE for 24 h. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 compared to control.

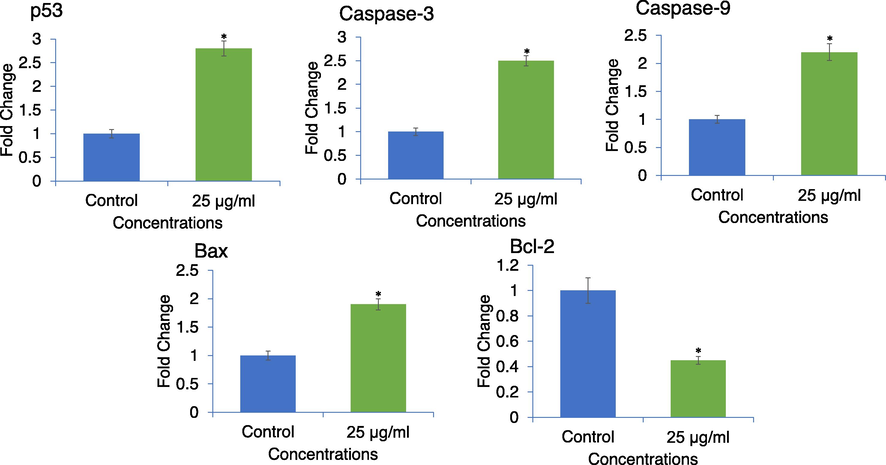

3.6 Apoptosis gene expression by qPCR

The fold change in the expression of apoptosis related genes (p53, caspase-3 and -9, Bax, Bcl-2) evaluated using RT-qPCR are summarized in Fig. 8. APPeE treated MDA-MB-231 cells showed upregulation of proapoptotic p53, Bax, caspase-3 and -9 genes and downregulation of antiapoptotic gene Bcl-2. With APPeE treatment, the expression of p53, Bax, caspase-3 and -9 was increased by 2.8-, 1.9-, 2.5- and 2.2-fold, respectively, and Bcl-2 was decreased by 1.55-fold as compared to control (Fig. 8).

Expression of apoptotic related genes in MDA-MB-231 cells analyzed by qPCR. Cells were exposed to 25 μg/ml of APPeE for 24 h. *p < 0.05 vs control.

3.7 HPTLC method development, validation and analysis of stigmasterol in Aloe perryi petroleum ether extract (APPeE)

The results of HPTLC method development, validation and analysis of stigmasterol in Aloe perryi petroleum ether extract (APPeE) have been provided in the Supplementary data (Supplementary File).

4 Discussion

Herein, we explored the anticancer potential and the mechanisms of APPeE-induced MDA-MB-231 cell death. The results showed that APPeE-induced a dose dependent strong cytotoxic effects on MDA-MB-231 cells with an IC50 value of 24.5 μg/ml and weak cytotoxicity on HEK-293 cells with an IC50 value of > 100 μg/ml after 24 h treatment. The cytotoxic potential of APPeE on decreasing the cancer cell viability has been proven according to our previous study in this concentration range (Al-Oqail et al., 2016). Aloe extracts and a number of Aloe compounds have been shown to ameliorate many diseases including cancer (Sánchez et al., 2020). Aloe vera extracts induced cytotoxicity in MCF-7 and HeLa cells have been reported via modulation of gene expression and induction of apoptosis (Hussain et al., 2015). Furthermore, aloe-emodin and aloesin, an isolated compound has also been possess anticancer activities (Chen et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2017). In this study, the isolated compound (stigmasterol) from A. perryi is amongst the most spread phytochemical in the plant Kingdom. Previously stigmasterol was reported from many plants of Aloe family, but to the best of our knowledge, it is isolated from A. perryi for the first time. The results of HPTLC analysis points towards the fact that the biomarker stigmasterol could be accountable for the cytotoxicity of APPeE. A significant cytotoxic effect of APPeE observed here against MDA-MB-231 cells might be because of the existence of compounds such as stigmasterol in the APPeE as quantified by HPTLC. There are various studies suggested that stigmasterol exert potential cytotoxic potential against various cancer cells (Lu et al., 2018) via apoptotic regulatory genes (Al-Fatlawi, 2019) and proteins such as caspase-3 and-9 (Bae et al., 2020). We have further determined the cytotoxic effect of APPeE on the cell morphology. The morphological alterations induced in MDA-MB-231 including cell shrinkage, reduced cell density, and damage membrane induced by APPeE are some features of apoptosis, as it has been previously suggested on cancer cells (Kanduc et al., 2002). Moreover, APPeE induced cell death in MDA-MB-231 cell line was evaluated by ROS generation after 24 h exposure. Our quantitative and qualitative analyses of ROS production as evident by a concentration-dependent increase in the green fluorescence of DCF-DA dye confirm the role of ROS in APPeE-induced cell death. It is well documented that many chemotherapeutic agents generate ROS, and is one of the mechanisms through which chemotherapeutic agents induced cancer cell death (Yang et al., 2018). Aloe-emodin, an anthraquinone extracted from plant has also been described to possess cancer cell death by ROS generation in MG63 cells (Li et al., 2016). In one of the studies, Tu et al. (2016), has revealed cytotoxic effects of aloe-emodin on human osteosarcoma cell line, MG-63 by increasing the cytochrome c and caspases through ROS signaling pathway. Therefore, we can imagine that overproduction of ROS induced by APPeE could be responsible for MDA-MB-231 cell death. In present investigation, the protein levels of caspase-3 and -9 were also studied. Our results exhibited a concentration-dependent increase in caspase-3 and -9 protein levels in APPeE induced MDA-MB-231 cells. These caspase activations may possibly be the mechanism through which APPeE can add to the cytotoxicity of MDA-MB-231 cells. The damaged mitochondrial membrane releases the cytochrome c which leads to caspase cascade and succeeding to cell death (Ried and Shi, 2004). The results of this study are in the agreement with other reports show that Phaseolus vulgaris plant extract induced caspase activated MDA-MB-231 cell death (Kumar et al., 2017). The human osteosarcoma cell death induced by aloe-emodin due to the increased level of caspase has also been reported (Tu et al., 2016). To examine the mechanism through APPeE exerts the cytotoxicity in MDA-MB-231, we further studied the apoptosis marker genes involved in this process. The effects of cytotoxic concentration of APPeE at molecular level through the expression of apoptosis related genes were measured. This is the first time, quantitative assessment demonstrated that cell exposure to 25 μg/ml of APPeE resulted 2.8-, 1.9-, 2.5-, 2.2 -fold increment in p53, Bax, caspase-3 and -9 genes expression, respectively. The Bcl-2 gene expression was also decreased by 1.55-fold. It is well documented that Bax is regulated by p53 and negatively controls expression of Bcl-2 (Miyashita et al., 1994). The apoptosis regulation is associated with an imbalance of expression of genes involved in cell death and proliferation (Reed, 1999). The gene of Bcl-2 family is reported to be involved in proapoptotic, Bax and antiapoptotic, Bcl-2 (Elmore, 2007). The over expression of pro-apoptotic genes p53, Bax, caspase-3 and -9 and down regulation of anti-apoptotic gene Bcl-2 confirm that APPeE has the capacity to induce MDA-MB-231 cell death through apoptotic pathway.

5 Conclusions

Together, we have shown a probable mechanism(s) by which Aloe perryi extract (APPeE) induced cytotoxicity and apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 cells. APPeE was also found to increase ROS generation, caspase-3 and -9 protein levels. An increase in the expression of p53, Bax, caspase-3 and -9 genes and decrease in Bcl-2 gene confirm that APPeE has the ability to induce apoptotic cell death in MDA-MB-231 cells. This study also provides the percentage of stigmasterol present in the APPeE by HPTLC analysis. The current investigation delivers an evidence of mechanism for in vitro studies by which APPeE-induced breast cancer cell death.

Acknowledgement

The authors are grateful to the Deanship of Scientific Research, King Saud University for funding through Vice Deanship of Scientific Research Chairs.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Phytosynthetic Ag doped ZnO nanoparticles: semiconducting green remediators. Open Chem.. 2018;16:556-570.

- [Google Scholar]

- Stigmasterol inhibits proliferation of cancer cells via apoptotic regulatory genes. Biosci. Res.. 2019;16:695-702.

- [Google Scholar]

- Screening of Yemeni medicinal plants for antibacterial and cytotoxic activities. J. Ethnopharmacol.. 2001;74:173-179.

- [Google Scholar]

- In vitro anti-proliferative activities of Aloe perryi flowers extract on human liver, colon, breast, lung, prostate and epithelial cancer cell lines. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci.. 2016;29:723-729.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nigella sativa seed oil suppresses cell proliferation and induces ROS dependent mitochondrial apoptosis through p53 pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. South Afr. J. Bot.. 2017;112:70-78.

- [Google Scholar]

- Al-Oqail, M.M., Al-Sheddi, E.S., Farshori, N.N., Al-Massarani, S.M., Al-Turki, E.A., Ahmad, J., Al-Khedhairy, A.A., Siddiqui, M.A., 2019. Corn Silk (Zea mays L.) Induced Apoptosis in Human Breast Cancer (MCF-7) Cells via the ROS-Mediated Mitochondrial Pathway. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 9789241.

- Stigmasterol causes ovarian cancer cell apoptosis by inducing endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondrial dysfunction. Pharmaceutics. 2020;12:488.

- [Google Scholar]

- A simple quantitative procedure using monolayer cultures for cytotoxicity assays (HTD/NR-90) J. Tissue Cult. Methods. 1985;9:7-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of the anticancer effects of Aloe vera and aloe emodin on B16F10 murine melanoma and NIH3T3 mouse embryogenic fibroblast cells. J. Fac. Pharm. Ist. Univ.. 2017;47:77-84.

- [Google Scholar]

- Exploring a novel target treatment on breast cancer: aloe-emodin mediated photodynamic therapy induced cell apoptosis and inhibited cell metastasis. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem.. 2016;16:763-770.

- [Google Scholar]

- GLOBOCAN, 2018. International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), World Health Organization (WHO). Estimated cancer incidence, mortality and prevalence worldwide in 2018. https://www.iarc.fr/en/media-centre/pr/2018/pdfs/pr263_E.pdf.

- Anticancer potential of aloes: antioxidant, antiproliferative, and immunostimulatory attributes. Planta Med.. 2012;78:843-852.

- [Google Scholar]

- The global breast cancer burden: variations in epidemiology and survival. Clin. Breast Cancer. 2005;6:391-401.

- [Google Scholar]

- Aloe vera inhibits proliferation of human breast and cervical cancer cells and acts synergistically with cisplatin. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev.. 2015;16:2939-2946.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phytofunctionalized silver nanoparticles: green biomaterial for biomedical and environmental applications. Rev. Inorg. Chem.. 2018;38:127-149.

- [Google Scholar]

- Augmented photocatalytic, antibacterial and antifungal activity of prunosynthetic silver nanoparticles. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol.. 2018;46:127-137.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prunus cerasifera Ehrh. fabricated ZnO nano falcates and its photocatalytic and dose dependent in vitro bio-activity. Open Chem.. 2018;16:141-154.

- [Google Scholar]

- Foliar-mediated Ag: ZnO nanophotocatalysts: green synthesis, characterization, pollutants degradation, and in vitro biocidal activity. Green Proc. Synth.. 2019;8:172-182.

- [Google Scholar]

- Carthami flos extract and its component, stigmasterol, inhibit tumour promotion in mouse skin two-stage carcinogenesis. Phytother. Res.. 1994;8:327-331.

- [Google Scholar]

- The genus ALOE (Asphodelaceae: Alooideae) in namaqualand, South Africa. Haseltonia. 2007;13:38-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antiproliferative and apoptotic effects of black turtle bean extracts on human breast cancer cell line through extrinsic and intrinsic pathway. Chem. Cent. J.. 2017;11:56.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mitochondrial pathway and endoplasmic reticulum stress participate in the photosensitizing effectiveness of AE-PDT in MG 63 cells. Cancer Med.. 2016;5:3186-3193.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and cytotoxicity of new stigmasterol derivatives. J. Chem. Soc. Pak.. 2018;40:715-721.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytotoxicity of the aqueous extract and organic fractions from Origanum majorana on human breast cell line MDA-MB-231 and human colon cell line HT-29. Adv. Pharmacol. Sci.. 2018;2018:3297193.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tumor suppressor p53 is a regulator of bcl-2 and bax gene expression in vitro and in vivo. Oncogene. 1994;9:1799-1805.

- [Google Scholar]

- Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J. Immunol. Methods. 1983;65:55-63.

- [Google Scholar]

- Studies of the in vitro anticancer, antimicrobial and antioxidant potentials of selected Yemeni medicinal plants from the island Soqotra. BMC Complement. Altern. Med.. 2009;9:7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Molecular mechanisms of caspase regulation during apoptosis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol.. 2004;5:897-907.

- [Google Scholar]

- Aloe genus plants: from farm to food applications and phytopharmacotherapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci.. 2018;19:2843.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pharmacological update properties of Aloe vera and its major active constituents. Molecules. 2020;25:1324.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biomimetic [MoO3@ ZnO] semiconducting nanocomposites: chemo-proportional fabrication, characterization and energy storage potential exploration. Renew. Energy. 2021;167:568-579.

- [Google Scholar]

- Aloe-emodin-mediated photodynamic therapy induces autophagy and apoptosis in human osteosarcoma cell line MG–63 through the ROS/JNK signaling pathway. Oncol. Rep.. 2016;35:3209-3215.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytotoxic effects of chlorophyllides in ethanol crude extracts from plant leaves. Evidence-based complement. Altern. Med.. 2019;2019:9494328.

- [Google Scholar]

- The role of cellular reactive oxygen species in cancer chemotherapy. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res.. 2018;37:266.

- [Google Scholar]

- Electro-catalyst [ZrO2/ZnO/PdO]-NPs green functionalization: Fabrication, characterization and water splitting potential assessment. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy.. 2021;46:19347-19362.

- [Google Scholar]

- Aloesin suppresses cell growth and metastasis in ovarian cancer SKOV3 cells through the inhibition of the MAPK signaling pathway. Anal. Cell. Pathol.. 2017;18:8158254.

- [Google Scholar]

Appendix A

Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2022.101968.

Appendix A

Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article: