Translate this page into:

High performance of pyrochlore like Sm2Ti2O7 heterojunction photocatalyst for efficient degradation of rhodamine-B dye with waste water under visible light irradiation

⁎Corresponding author at: UNESCO-UNISA Africa Chair in Nanoscience’s/Nanotechnology Laboratories, College of Graduate Studies, University of South Africa (UNISA), Muckleneuk Ridge, P O Box 392, Pretoria, South Africa. kaviyarasuloyolacollege@gmail.com (K. Kaviyarasu)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Binary metal oxide heterojunctions possibly will exclude the recombination of photogenerated charge carriers via interfacial charge transfer in assessment among the single-component photocatalytic material. Highly ordered samarium doped titania nanosphere have paid more attention to the exclusion of toxic organic pollutants. Tuning the shape, size, morphology, bandgap and defect optimization of titanium oxides (Sm2Ti2O7) improved as an enhanced catalyst which was synthesized by using the capping agent also acts as a reducing agent. Herein, we examine an environmentally pleasant Sm2Ti2O7 nanosphere with its various properties via assorted characterization techniques and wrapping of nanosphere makes them appropriate catalysts for the degradation of toxic dyes and show the highest efficiency via irradiation of visible light by declining the option of the exciton-recombination process. Therefore, the photocatalyst was found to produce reactive oxygen species (ROS) both in the presence and absence of light, which is responsible for the decomposition of dyes into small fractions. In addition, HRTEM study reveals that the nanospheres are highly porous nature with high active surface area and small grain size are reported in detail.

Keywords

Sm2Ti2O7 nanosphere

Optical properties

Electron spectroscopy

Rhodamine-B dye

Photocatalytic activity

1 Introduction

Toxic organic dyes with highly complex structures play an elemental function in textile industries (Maria Magdalane et al., 2017). During the past few years, specifically industries like textile, leather, printing inks, paints, rubber, art and craft, paper, plastics, drug and cosmetics, food, utilize verity of synthetic organic dyes and pigments for the colouring purposes (Chen et al., 2010). Among all industries, the major quantity of dyes is released from the textile industries and pollute the water nearly 17–20% observed by the world bank (Amanulla et al., 2018). All these dyes are highly carcinogenic and toxic to the environment, which leads to major damages to the living organisms (Miao et al., 2018). Degradation of dyes is quite difficult by common methods like coagulation-flocculation, filtration, precipitation, solvent extraction, electrochemical treatment, ion exchange and adsorption due to the complicated chemical structure and more thermal stability of the dye effluent (Maria Magdalane et al., 2017). Titania (TiO2) is a glowing and significant n-type semiconductor metal oxide for the degradation of organic dye effluent due to its towering stability (Binas et al., 2018). Pure titania has the minimum quantum efficiency and the wider bandgap of TiO2 confines its catalytic applications on the illumination of various light sources (Maria Magdalane et al., 2017). Recently, researches followed advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) which are ozonisation, Fenton, TiO2 photocatalysis, photo-Fenton and photolysis using H2O2, etc (Manjunath et al., 2018). Among all the type of catalyst, AOPs with TiO2 (anatase), becomes a most frequently used important semiconductor photocatalyst on irradiation of UV light source for the detoxification of pollutants (Magdalane et al., 2016). Also, a least amount percentage of light sources were used by the catalyst which leads to incomplete degradation of dyes in the industrial wastewater (Koivistoa et al., 2018). Hence, all the catalysts have been to modify for the development of high-quality catalysts like metal oxide/metal oxide, metal/TiO2, chalcogenides, etc in order to use the wide spectrum of visible light (IyyappaRajan et al., 2017). In the current literature work, the transition metal oxide and rear earth metal oxide doped titania has been carried out to stabilize the bandgap acting a major task in the photocatalytic properties of titania on the illumination of visible light (Maria Magdalane et al., 2018). The rare earth metal doped titania is developed in recent times and shows the enhanced rate of degradation efficiency on risky organic chemicals in the wastewater (Deilynazar et al., 2015).

In current research, many works have been committed for upgrading the photocatalytic activities of TiO2, like depositing non-metal ions or noble metals (Nakamura et al., 2016). Commonly, the doping of other foreign ions is capable for the configuration of a new energy level in between the high energy conduction band and low energy valence bands of titania (Magdalane et al., 2018). Besides of titania nanostructures, A2B2O7 pyrochlore is have great attention among the researches due to its multifunctional nature like radiation damage resistance, more ionic conductivity, Li-ion battery, ferroelectricity, photoluminescence, superconductivity, laser materials, fuel cells and geometrically perturbed magnetism (Reddy et al., 2018). Most of these nanostructures have high-temperature piezoelectric property, since it has high curie points and superior thermal stability like Bi2Ti2O7, La2Ti2O7, Nd2Ti2O7, Pr2Ti2O7, Ln2Zr2O7 (Wang et al., 2011). Furthermore, the defects in the structure, intrinsic carrier effects and disorder on oxygen diffusion on ionic conductivity in pyrochlores. The DFT calculations of various pyrochlore structure ofrare earth metal oxide was investigated apparently (Hector and Wiggin, 2004).

Many new technologies have been utilised to achieve active Sm2Ti2O7 pyrochlore nanostructure, like hydrothermal processing (Lelievre and Marchet, 2017), co precipitation, sol-gel method and solution combustion method. In general, among all the methods the sol-gel method is a dominant approach to fabricate inorganic materials in recent times. In the above method, a solid precursor is hydrolysed to form a colloidal sol solution. On further reaction process the new bonds were formed along with the sol particles, these results in an immeasurable network of gel particles which yield the active nanomaterials on heating. The important advantages of this method over the other conventional method are high-purity materials and homogeneous crystalline structures can be prepared even at low temperatures. In our present work, we report the samarium doped TiO2 with a great deal of significance due to its exceptional electrons in the f and d orbital structures. Herein we synthesis samarium doped TiO2 by the biopolymer-mediated method and effectively applied as the competent catalyst for the degradation of dye under visible-light illumination. The rare earth metal oxide doped titania increase the distinctive UV absorption capability, high electrical conductivity, stability and huge oxygen storage space aptitude of samarium which appreciably improve the photocatalytic efficiency of TiO2.

2 Experimental work

2.1 Synthesis ofSm2Ti2O7 nanospheres

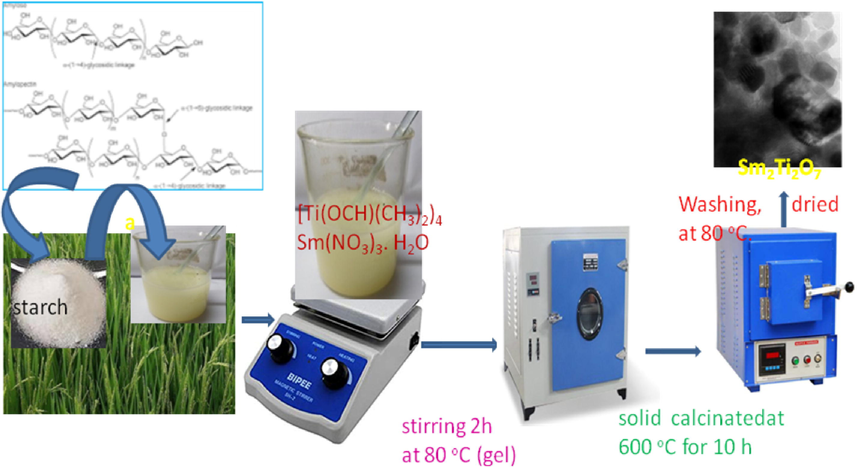

Titanium isopropoxide [Ti(OCH)(CH3)2)4], Samarium nitrate [Sm(NO3)3·H2O], ethanol were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (E-Merck 99.99%) and utilised as analytical grade without any further purification. Sm2Ti2O7 nanosphere was synthesised by using starch as a chelating agent. In the synthesis process, 5 g of starch was dissolved in 50 mL of pure water in the hot condition. 0.1 M Titanium isopropoxide (TIP) was prepared by using ethanol as solvent and 0.11 M samarium nitrate [Sm(NO3)3·H2O] solution was prepared with double deionised water. From the above solution, 2:1 ratio Titanium isopropoxide and samarium nitrate was mixed with constant stirring. To this mixture, the solution of starch was added with continuous stirring for 2 h at 60 °C. The resulting transparent sol was cooled and boiled again in water bath at 80 °C to form a gel. The obtained gel was heated at 150 °C in a hot air oven for 10 h to get a solid. Finally, the sponge like solid was obtained which was ground in the motor and pestle to get a fine powder and this powder sample was calcinated at 600 °C for 10 h in the high temperature box furnace. The obtained solid sample was cooled, and the impurity removed by using ethanol and dried out in the oven 80 °C. The schematic representation for the synthesis of Sm2Ti2O7nanosphere as shown in Fig. 1.

Schematic representation for the synthesis of Sm2Ti2O7 nanosphere.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Crystalline structural determination for Sm2Ti2O7

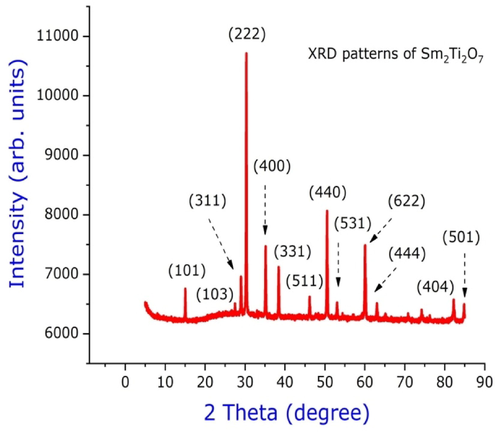

The crystalline phases of Sm2Ti2O7 nanosphere were investigated via powder XRD as shown in the Fig. 2. The crystallization of Sm2Ti2O7 nanosphere was depends on its calcination’s temperature. Samarium doped Titania calcined at 600 °C was found to be pyrochlore structure with Fd3m crystal lattice. The intensities of the diffraction peaks in accordence with (JCPDS No.73–1699) becomes more at this calcination temperature. Furthermore, the homogenous pyrochlore strucutre of the sample were observed at this calcinations temperature without any other phases transformations and impurities in the samples. The crystallite size of Sm2Ti2O7 nanosphere was calculated from the Scherrer formula for the samples. The pyrochlore Sm2Ti2O7 samples crystallite sizes were found to be 23 nm for the samples calcined at 600 °C (Angel Ezhilarasi et al., 2018).

XRD of Sm2Ti2O7 nanosphere annealed at 600 °C.

3.2 Optical properties of Sm2Ti2O7

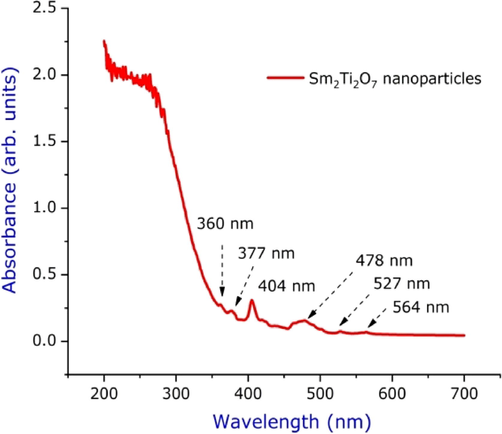

The optical properties of Sm2Ti2O7 nanosphere were examined by UV–vis absorption spectrum as shown in the Fig. 3. The maximum absorption peaks appear at 404 and 478 nm, the shift in the absorption peak towards red shift is due to the formation of smaller size of Sm2Ti2O7 nanosphere when compared to the bulk titania Eg = 3.2 eV (Valsalam et al., 2019). The appearance of red shift is due to quantum size effect and confinement effects size. The bandgap of the Sm2Ti2O7 nanosphere were found to be 2.6 eV (Gao et al., 2016). The bandgap of the Sm2Ti2O7 nanosphere was reduced due to its calcination’s temperature. The reduction in the bandgap provides the samples to absorption of higher energy photons from the visible light.

UV spectrum of Sm2Ti2O7 nanosphere annealed at 600 °C.

3.3 Microstructure analysis of Sm2Ti2O7

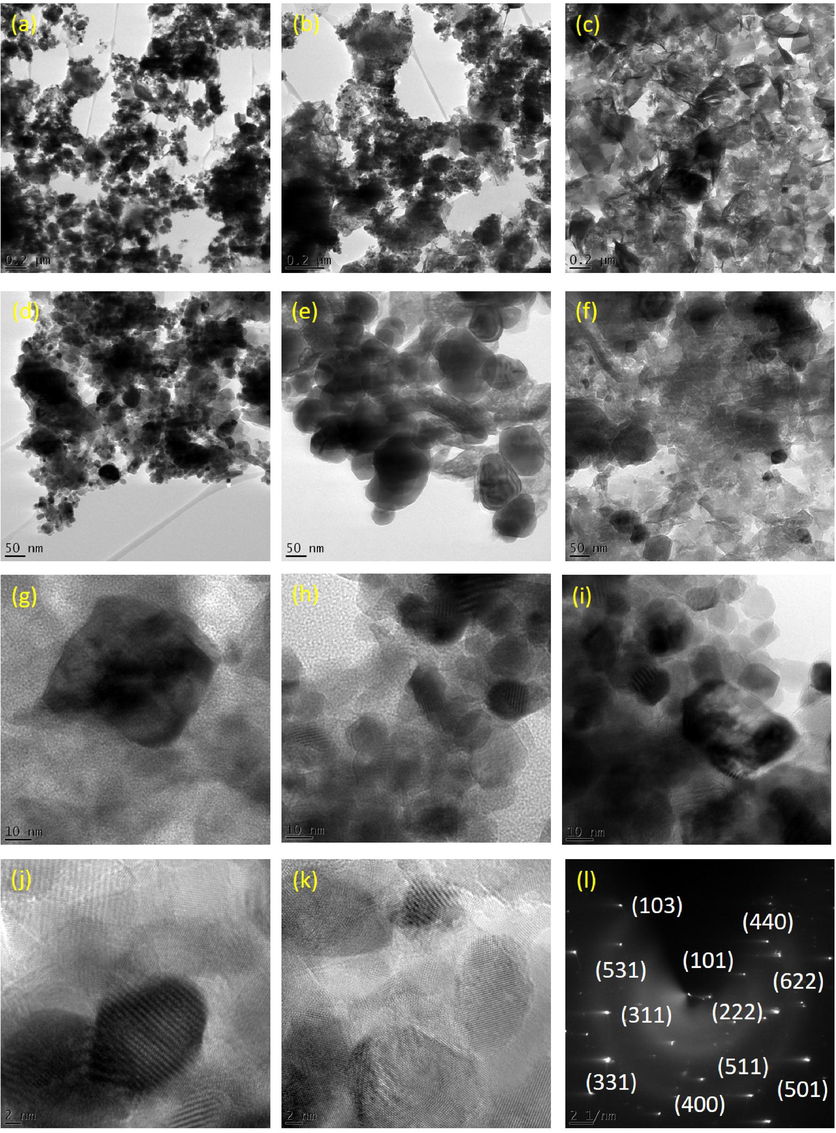

The morphological analysis of Sm2Ti2O7 was investigated by HRTEM images at different magnifications. The porous structures of Sm2Ti2O7 nanosphere have large specific surface area at all magnifications (Nanamats et al., 1974). The images of HRTEM appeared as an agglomerated and not exactly spherical and the average grain size is about 12 nm, which agrees with results of XRD analysis, while the morphology of oxide provided using FESEM and the results emphasize agreement with HRTEM about the agglomeration of particles as shown in Fig. 4(a-l). The samples were additional deeply magnified, and this proved an agglomerated spherical nanosphere-like morphology (Ning et al., 2010). This type of interrelated sphere-shaped porous nanostructure provides distinctive pores with a more specific active surface area. Such a crystalline structure must afford as an enhanced catalytic property (Gao et al., 2012). The morphology of nanosphere described that it may be used for recovering catalytic performance for high energy storage application (Anand et al., 2017). As evident from the literature, the size, shape and dimensions of nanostructures determines the various properties of the samples (Shao et al., 2012). As a result, by modification of the size, morphology and optical properties of the nanomaterials, the catalytic nature and selectivity can be extensively improved (Rabanal et al., 1999). The SAED pattern of Sm2Ti2O7 nanosphere proves the polycrystalline nature of the nanostructure (Magdalane et al., 2019).

(a-l) HRTEM images of Sm2Ti2O7 nanosphere annealed at 600 °C.

3.4 Photocatalytic activity tests Sm2Ti2O7

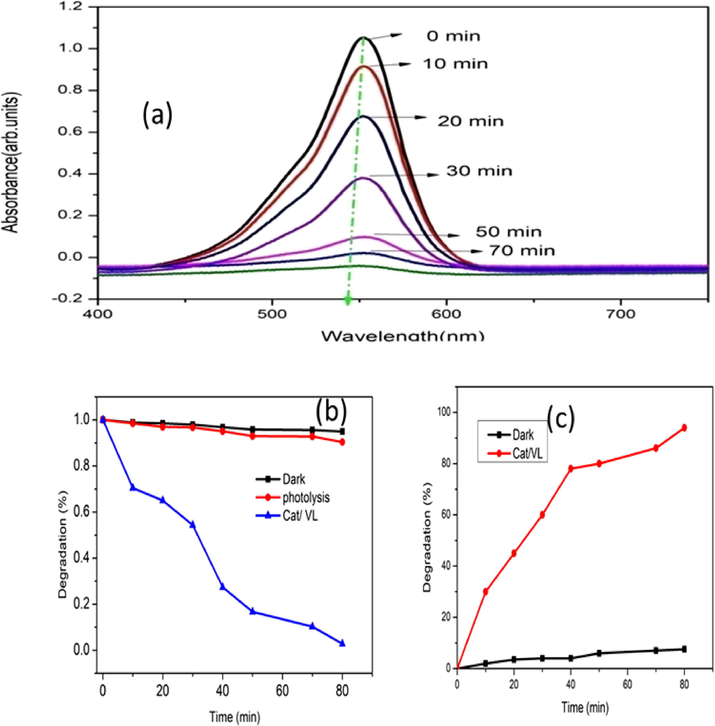

The photocatalytic decomposition of industrial pollutant like synthetic RhB dye was investigated using synthesised Sm2Ti2O7 nanosphere on irradiation of visible light. The decomposition efficiency of the synthesised samples was carried out and the absorption spectra of the resulted solution with Sm2Ti2O7 nanosphere and blank were plotted with time (min) on illumination of visible light shown in the Fig. 5(a–c) (Nadjia et al., 2018). The synthetic RhB dye shows the absorption peaks at 498 nm with the colour change from red to colourless, which proves the decomposition of dye. The ratios between the initial concentration (Co) and the concentration at time (C) of the dye (C/Co) plotted vs time, to evaluate the effectiveness of the degradation in diverse condition (Kaviyarasu et al., 2017). The degradation efficiency of the synthesised samples found to be 94% is shown in the Fig. 5(c). The photodecomposition competence is superior for Sm2Ti2O7 nanosphere sample. This photocatalytic experiment with the catalyst has better effect due to the more active surface area, advanced capability in the direction of absorption of visible light, lesser size effect with prominent diffusion. These extraordinary qualities of the Sm2Ti2O7 nanosphere typically direct to an enhanced the photodegradation efficiently.

(a) UV–vis absorption spectra of RhB, (dye concentration 5 mg/L, pH 9/40 mg Cat, 80 min for the reaction completion) (b) C/Co vs irradiation time (c) degradation % vs irradiation time.

3.5 Mechanism of decomposition of RhB via Sm2Ti2O7 nanosphere

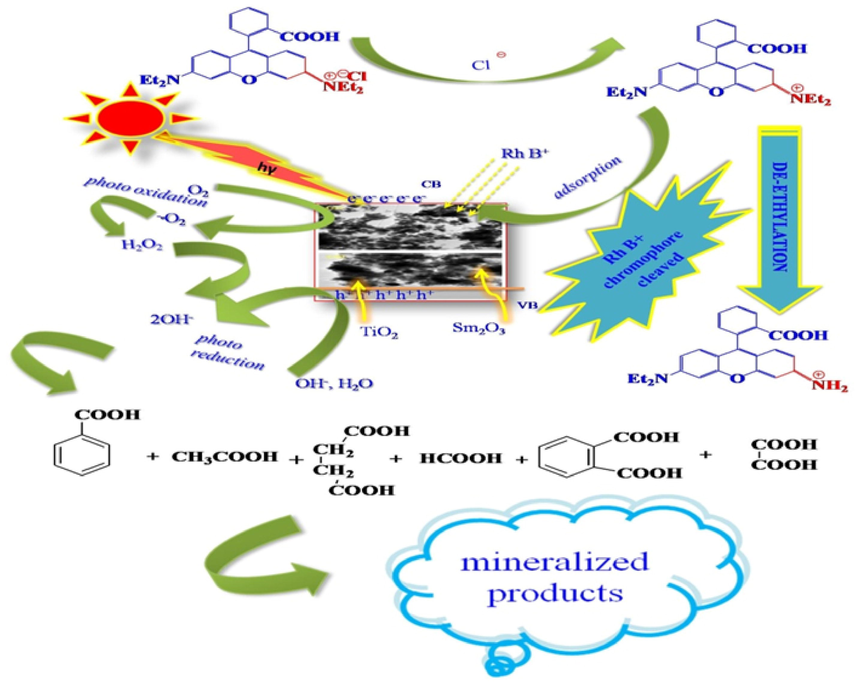

The reaction mechanism involved in the degradation process of RhB dye with a photocatalyst via irradiation of visible light discussed in detail; Excitons are created on the surface of the photocatalyst as shown in Fig. 6. The mixture of dye solution and photocatalyst is expose via excess of visible light, the partition of electron hole can be ascribed, when the electron from valence band is absorbs photons with high energy (hv > Eg) and gets excited to conduction band.

General mechanism in degradation process of RhB dye with a photocatalyst via irradiation of visible light.

The proposed mechanism in the decomposition reaction is a generation of photogenerated holes and electrons during the illumination of light in the mixture solution. The photogenerated holes oxidise the surface hydroxyl ions to its corresponding hydroxyl radicals (OH.) and the photogenerated electrons takes the surface oxygen molecule produce superoxide radical (O2−), which is again reduced to hydroperoxyl radical followed by highly oxidising agent hydrogen peroxide and finally hydroxyl radicals (OH.). In the photocatalytic reaction the organic pollutant RhB dye initially adsorbed on the catalytic surface and simultaneously it adsorbed the reactive oxygen species. During the reaction process successive intermediates are oxidized in numerous steps until mineralization to inorganic acids, water and carbon dioxide by the oxidizing species generated in the process. Many literature works reported that the unadulterated metal oxides nanoparticles show the way to quicker recombination of excition pairs, leads to minimise the degradation of toxic dyes were as binary metal oxides drawn out the recombination process and superior relocation effectiveness of e+/holes, ensuing enrichment photodegradation of toxic organic dyes. RhB + hν(visible light) → RhB* RhB*+TiO2 → RhB•++TiO2(e–) TiO2 + hν → TiO2(e–+h+) Sm2O3 + hν → Sm2O3(e–+h+) e–(CB,TiO2) + O2 → O2•– h+(VB,TiO2) + H2O → TiO2 + H+ +HO•– RhB/RhB•++(O2•–+h++HO•–)(ROS) → mineralized products → CO2 + H2O

4 Conclusion

Samarium doped Titania were successfully developed by biopolymer - mediated method for deterioration of Rhodamine-B dye from the polluted waste water. Sm2Ti2O7 nanosphere were analysed by a different characterisation analysis to describe their various properties like active surface morphology, size and optical activity. The XRD reveals that the synthesised Sm2Ti2O7 nanospheres have the high purity and smaller grain size with good crystallinity. The degradation of Rhodamine-B dye was carried out at different parameters and photocatalytic efficiency was observed nearly 94% owing to the smaller grain size, high active surface area, and better absorption of light source with prominent diffusion of dyes. These extraordinary qualities of the samples typically direct to an enhanced photodegradation efficiently. Interestingly, prepared nanostructures revealed the promising growth inhibition of bacteria. The mutual effect of excitons pair recombination, crystallinity and active surface area accountable for the superior photocatalytic and antibacterial activity.

Acknowledgment

The authors extend their appreciation to The Researchers supporting project number (RSP-2019/108) King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Antibacterial, magnetic, optical and humidity sensor studies of β-CoMoO4 – Co3O4 nanocomposites and its synthesis and characterization. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B: Biology 2018

- [Google Scholar]

- Bio-synthesis of silver nanoparticles using agroforestry residue and their catalytic degradation for sustainable waste management. J. Cluster Sci.. 2017;28:2279-2291.

- [Google Scholar]

- Green, synthesis of NiO nanoparticles using Aegle marmelos leaf extract for the evaluation of in-vitro cytotoxicity, antibacterial and photocatalytic properties. J. Photoch. Photobiol. B: Biology.. 2018;180:39-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- Study of innovative photocatalytic cement – based coatings: the effect of supporting materials. Constr. Build. Mater.. 2018;168:923-930.

- [Google Scholar]

- Semiconductor-based Photocatalytic Hydrogen Generation. Chem. Rev.. 2010;110:6503-6570.

- [Google Scholar]

- First-principles insight sint of magnetism: a case study on some magnetic pyrochlores. J. Magn. Magn. Mater.. 2015;393:127-131.

- [Google Scholar]

- The anisotropic conductivity of ferroelectric La2Ti2O7ceramics. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc.. 2016;89:121-135.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ferroelectricity of Pr2Ti2O7 ceramics with super-high curie point. Adv. Appl. Ceram.. 2012;112:69-74.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and structural study of stoichiometric Bi2Ti2O7 pyrochlore. J. Solid State Chem.. 2004;177:139-145.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mansoor-Ali Vaali-Mohammed, Green-fuel-mediated synthesis of self-assembled NiO nano-sticks for dual applications - photocatalytic activity on Rose Bengal dye and antimicrobial action on bacterial strains. Mater. Res. Express. 2017;4(8):085030

- [Google Scholar]

- Antiproliferative effects on human lung cell lines A549 activity of cadmium selenide nanoparticles extracted from cytotoxic effects: investigation of bio-electronic application. Mater. Sci. Eng., C. 2017;76:1012-1025.

- [Google Scholar]

- Particle emission rates during electrostatic spray deposition of TiO2 nanoparticle-based photoactive coating. J. Hazard. Mater.. 2018;341:218-227.

- [Google Scholar]

- Structure and properties of Bi2Ti2O7 pyrochloretype phase stabilized by lithium. J. Alloys Compd.. 2017;45:45-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- Self-cleaning mechanism of synthesized SnO2/TiO2 nanostructure for photocatalytic activity application for waste water treatment. Surf. Interfaces. 2019;17:100346

- [Google Scholar]

- Photocatalytic activity of binary metal oxide nanocomposites of CeO2/CdO nanospheres: investigation of optical and antimicrobial activity. J. Photochem. Photobiol., B. 2016;163:77-86.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation on La2O3 garlanded ceria heterostructured binary metal oxide nanoplates for UV/ Visible light induced removal of organic dye from urban wastewater. S. Afr. J. Chem. Eng.. 2018;26:49-60.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ionic liquid assisted hydrothermal synthesis ofTiO2 nanoparticles: photocatalytic and antibacterialActivity. J. Mater. Res. Technol.. 2018;7(1):7-13.

- [Google Scholar]

- Photocatalytic decomposition effect of erbium doped cerium oxide nanostructures driven by visible light irradiation: Investigation of cytotoxicity, antibacterial growth inhibition using catalyst. J. Photochem. Photobiol., B. 2018;185:275-282.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation on the heterostructured CeO2/Y2O3 binary metal oxide nanocomposites for UV/Vis light induced photocatalytic degradation of Rhodamine-B dye for textile engineering applications. J. Alloys Compd.. 2017;727:1324-1337.

- [Google Scholar]

- Facile synthesis of heterostructured cerium oxide/yttrium oxide nanocomposite in UV light induced photocatalytic degradation and catalytic reduction: Synergistic effect of antimicrobial studies. J. Photochem. Photobiol., B. 2017;173:23-34.

- [Google Scholar]

- Photocatalytic degradation effect of malachite green and catalytic hydrogenation by UV–illuminated CeO2/CdO multilayered nanoplatelet arrays: Investigation of antifungal and antimicrobial activities. J. Photochem. Photobiol., B. 2017;169:110-123.

- [Google Scholar]

- Photocatalytic degradations of three dyes with different chemical structures using ball-milled TiO2. Mater. Res. Bull.. 2018;97:109-114.

- [Google Scholar]

- CeO2 nanoscale particles: Synthesis, characterization and photocatalytic activity under UVA light irradiation. J. Rare Earths.. 2018;87:1-13.

- [Google Scholar]

- Theoretical and experimental investigation of defect formation / migration in Gd2Ti2O7: General rule of oxide-ion migration in A2B2O7 pyrochlore. AIPAdvances. 2016;6:115003

- [Google Scholar]

- Piezoelectric strontium niobate and calciumniobate ceramics with super – high curie points. J. Am. Ceram. Soc.. 2010;93:1409-1413.

- [Google Scholar]

- Structure and reaction with lithium of tetragonal pyrochlore-like compound Sm2Ti2O7. J. Mater. Process. Technol.. 1999;92:529-533.

- [Google Scholar]

- Equilibrium and kinetic studies of the adsorption of acid blue 9 and Safranin O from aqueous solutions by MgO decked FLG coated Fuller's earth. J. Phys. Chem. Solids. 2018;123:43-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- Investigation of microstructure in ferroelectric lead-free La2Ti2O7 thin film grown on (001)SrTiO3 substrate. Cryst. Eng. Comm.. 2012;14:6524-6533.

- [Google Scholar]

- Rapid biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from the leaf extract of Tropaeolummajus L. and its enhanced in-vitro antibacterial, antifungal, antioxidant and anticancer properties. J. Photochem. Photobiol., B. 2019;191:65-74.

- [Google Scholar]

- Energetics and concentration of defects in Gd2Ti2O7 and Gd2Zr2O7 pyrochlore at high pressure. Acta Mater.. 2011;59:1607-1618.

- [Google Scholar]