Translate this page into:

Genetic diversity and antifungal activities of the genera Streptomyces and Nocardiopsis inhabiting agricultural fields of Tamil Nadu, India

⁎Corresponding authors. kumar.m@icar.gov.in (Murugan Kumar), saxena461@yahoo.com (Anil Kumar Saxena)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Actinomycetes receives much attention as plant-beneficial bacteria due to their distinct morpho-physiological, plant growth promoting and antifungal properties. Among the actinomycetes, members of the genus Streptomyces are of specific interest due to their metabolic versatility and ubiquity. The diversity of Streptomyces in different crop fields of Tamil Nadu has not been explored early. In this study, we explored phylogenetic diversity, morphological heterogeneity, and antifungal properties of cultivable actinomycetes isolated from the rhizosphere and bulk soils of different crops collected from 20 distinct districts of Tamil Nadu. A total of 65 actinomycetes were isolated from 40 soil samples including rhizosphere and bulk soils of different crops, and their diversity was analyzed using the 16S rRNA gene sequence. They were then characterized for cultural characteristics and antifungal activity against four fungal strains Fusarium udum, Fusarium oxysporum f.sp. ciceri, Macrophomina phaseolina and Sclerotium rolfsii. Out of the 65 isolates sequenced, 45 were found to be closely related to Streptomyces spp. while the remaining 20 showed similarities with Nocardiopsis spp. Cultural characterization on four different ISP media showed immense diversity among the members of the genera Streptomyces and Nocardiopsis. The strains of Streptomyces spp. and Nocardiopsis spp. showed varying levels of antifungal activity with all strains found antagonistic against both Fusarium udum and Fusarium oxysporum f.sp. ciceris. All the strains obtained in this study have been accessioned at the National Agriculturally Important Microbial Culture Collection (NAIMCC) to increase the database of characterized strains belonging to these two genera in the collection.

Keywords

Actinomycetes

Antifungal activity

Streptomyces spp.

Nocardiopsis spp.

1 Introduction

Actinomycetes are an important group of soil bacteria that are found to be more prevalent in dry soils than wet soils. Soil actinomycetes are known for their plant growth promotional activity as they exhibit various useful traits (Ma et al., 2020). They can also produce a variety of secondary metabolites, many of which are antibacterial or antifungal (Olanrewaju and Babalola, 2019). Most antibiotics used in human medicine are metabolites of actinomycetes, with many of them originating from Streptomyces spp. (Ma et al., 2020). The ability to synthesize a variety of chemical substances such as antibiotics, enzymes, and anti-tumor medicines, made Streptomyces spp. most common genus used in the pharma industry (Chaudhary et al., 2013). In soil, they grow as substrate mycelium and produce a range of enzymes including chitinase, xylanase and cellulase that breakdown complex organic polymers into constituent simple sugars (Seipke et al., 2012) thereby playing a direct role in biogeochemical cycles. They are significant candidates for natural fertilizers because of their ability to cycle nutrients. They are effective colonizers of rhizosphere and rhizoplane tissues with the potential to enhance plant growth, and development and boost yield (Dias et al., 2017). Streptomyces spp. promote plant growth through the production of phytohormones like auxins, cytokinins, and gibberellins, additionally they produce 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate (ACC) deaminase whose activity is important in the suppression of plant stress (Sadeghi et al., 2012; Verma et al., 2011). They are implicated in phosphate solubilization (Jog et al., 2014) and siderophore production (Verma et al., 2011) as well. Yet the most important role of Streptomyces spp. in agriculture is their ability to control phytopathogens owing to their traits; siderophore production, antibiotics production and volatile compounds secretion (Olanrewaju and Babalola, 2019).

Isolation, morphological, biochemical, physiological, and molecular characterization of Streptomyces spp. are reported in many studies (Taddei et al., 2006). Taddei et al. (2006) studied the biochemical and morphological characterization of 71 Streptomyces spp. isolated from soil samples of Venezuela, of them 67 isolates were new strains. In a recent study, Kaur et al. (2019) tested a potent Streptomyces strain MR14 with antifungal and plant growth promoting properties. Cell free extracts of MR14 showed potent antagonistic activity against 13 different fungal phytopathogens. Despite their multifarious role, Streptomyces found beneficial to plants and agriculture overall, received lesser interest as compared to Streptomyces spp. studied for their role in pharmaceuticals (Rey and Dumas, 2017). It is only imperative, that the exploration of the phylogenetic and morphological diversity of this group of bacteria and enriching their cultural database could lead to identifying strains with unique potential. Agricultural fields especially plant rhizosphere is an important source of potent Streptomyces spp. with antagonistic activity against plant pathogens. In the present study, an attempt was made to isolate Streptomyces spp. from different crop rhizosphere and bulk soil samples collected from Tamil Nadu, India. The resultant isolates were characterized for morphological diversity, genetic diversity, and antagonistic potential against select phytopathogenic fungi. All the actinomycetes isolated in this study were submitted to the National Agriculturally Important Microbial Culture Collection (NAIMCC), a constituent unit of ICAR-National Bureau of Agriculturally Important Microorganisms, Mau India.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Sample collection

A total of 40 soil samples including rhizosphere of different crops and bulk soils were collected in sterile bags from various locations in Tamil Nadu, India, details of the samples are depicted in Table 1. For rhizosphere samples, standing crops were uprooted at five random sites in a field and soils adhered to the roots were collected in a sterile poly bag. For bulk soil, the top 15 cm soil core was collected from five random sites in a sterile poly bag from each site. The samples once brought to the laboratory were shade dried aseptically and stored in a cold room (4 °C) until further processing.

GPS location

Address

Sample type

Strain no

9°53′22.0″N 78°09′22.0″E

Chinthamani, District Madurai, Tamil Nadu

Bulk soil coconut field

TN1, TN2

9°40′9.0″N 78°05′34.0″E

Kariapatti, District Virudhunagar, Tamil Nadu

Bulk soil after harvest of maize

TN3, TN4

9°29′37.0″N 78°06′25.0″E

Aruppukkottai, District Virudhunagar, Tamil Nadu

Bulk soil castor field

TN5, TN7

9°23′30.0N 78°07′40.0 E

Pandalgudi, District Virudhunagar, Tamil Nadu

Sunflower rhizosphere

TN6, TN8

9°08′50.0″N 78°00′23.0″E

Ettaiyapuram, District Thoothukkudi, Tamil Nadu

Bulk soil Jatropha field

TN9, TN10

8°51′04.0″N 78°07′15.0″E

Thoothukudi, Thoothukkudi District, Tamil Nadu

Sorghum rhizosphere

TN11, TN12

9°00′24.0″N 78°12′04.0″E

Vaippar, District Thoothukkudi, Tamil Nadu

Chilli rhizosphere

TN13, TN14

9°07′13.0″N 78°24′32.0″E

Sayalkudi, District Ramanathapuram, Tamil Nadu

Palm field bulk soil

TN15, TN16

9°13′17.0″N 78°36′37.0″E

Keerandai, District Ramanathapuram,Tamil Nadu

Rice rhizosphere

TN17, TN18

9°18′01.0″N 78°49′19.0″E

Pallamerkkulam, District Ramanathapuram, Tamil Nadu

Rice rhizosphere

TN19, TN20

9°22′57.0″N 78°50′08.0″E

Veethi, District Ramanathapuram, Tamil Nadu

Rice rhizosphere

TN21, TN22

9°37′21.0″N 78°55′50.0″E

Uppur, District Ramanathapuram, Tamil Nadu

Rice rhizosphere

TN23, TN24

10°03′58.0″N 79°13′48.0″E

Mumpalai, District Pudukkottai Tamil Nadu

Rice rhizosphere

TN25, TN26

10°18′10.0″N 79°20′27.0″E

Chinnaavudaiyarkoil, District Thanjavur, Tamil Nadu

Rice rhizosphere

TN27, TN28

10°25′32.0″N 79°32′52.0″E

Udayamarthandapuram, District Thiruvarur, Tamil Nadu

Rice rhizosphere

TN29, TN30

10°25′09.0″N 79°47′33.0″E

Kuravapulam, Nagapattinam District, Tamil Nadu

Rice rhizosphere

TN31, TN32

10°37′47.0″N 79°47′08.0″E

Meenamanallur, Nagapattinam District, Tamil Nadu

Rice rhizosphere

TN33, TN34

11°06′06.0″N 79°49′57.0″E

Chinnamedu, Mayiladuthurai District, Tamil Nadu

Rice rhizosphere

TN35, TN36

11°13′36.0″N 79°43′24.0″E

Sirkali, Mayiladuthurai District, Tamil Nadu

Rice rhizosphere

TN37, TN38

11°30′45.0″N 79°43′11.0″E

Chinnakomatti, District Cuddalore, Tamil Nadu

Rice rhizosphere

TN39, TN40

12°43′37.0″N 80°11′23.0″E

Thiruporu, District Chengalpattu, Tamil Nadu

Rice rhizosphere

TN41, TN42

12°53′48.0″N 80°14′50.0″E

Panaiyur, District Chennai, Tamil Nadu

Bulk soil coconut field

TN43, TN44

12°39′32.0″N 79°57′01.0″E

Grand Southern Trunk Road, Chengalpattu District Tamil Nadu

Rice rhizosphere

TN45, TN46

12°22′20.0″N 79°47′39.0″E

Kadamalaiputhur, District Kanchipuram, Tamil Nadu

Groundnut rhizosphere

TN47, TN48

12°11′02.0″N 79°37′25.0″E

Tindivanam, District Viluppuram, Tamil Nadu

Bhendi rhizosphere

TN49, TN50

11°40′51.0″N 79°17′18.0″E

Ulundurpet, District Kallakurichi, Tamil Nadu

Grassland

TN51

11°30′47.0″N 79°06′03.0″E

Kalpadi North, District Perambalur, Tamil Nadu

Brinjal rhizosphere

TN52

11°12′42.0″N 78°52′56.0″E

Pichandarkovil, District Tiruchirappalli, Tamil Nadu

Rice rhizosphere

TN53

10°54′11.0″N 78°43′30.0″E

Melapachchakudi, District Pudukkottai, Tamil Nadu

Rice rhizosphere

TN54

10°39′33.0″N 78°35′33.0″E

Kallupatti, District Tiruchirappalli, Tamil Nadu

Sorghum rhizosphere

TN55

10°25′40.0″N 78°26′07.0″E

Karungalakudi, District Madurai, Tamil Nadu

Brinjal rhizosphere

TN56

10°08′35.0″N 78°21′17.0″E

Kalikulam, District Tirunelveli, Tamil Nadu

Rice rhizosphere

TN57

9°59′50.0″N 78°15′23.0″E

Kalligudi, District Madurai, Tamil Nadu

Rice rhizosphere

TN58

9°43′33.0″N 77°58′46.0″E

Maniparaipatti, District Virudhunagar, Tamil Nadu

Redgram rhizosphere

TN59

9°25′23.0″N 77°55′08.0″E

Tenkasi, District Tenkasi, Tamil Nadu

Maize rhizosphere

TN60

9°12′41.0″N 77°47′45.0″E

Sankarankovil, District Tenkasi, Tamil Nadu

Rice rhizosphere

TN61

9°15′24.0″N 77°39′57.0″E

Alagiapandiapuram,District Tirunelveli, Tamil Nadu

Lemon rhizosphere

TN62

8°55′33.0″N 77°38′41.0″E

Palayamkottai, District Tirunelveli, Tamil Nadu

Rice rhizosphere

TN63

8°44′38.0″N 77°44′54.0″E

Amarapuram, District Thoothukudi, Tamil Nadu

Bulk soil banana field

TN64

8°32′31.0″N 78°06′43.0″E

Amarapuram, District Thoothukudi, Tamil Nadu

Bulk soil coconut field

TN66

2.2 Isolation of actinomycetes from soil

A selective media containing basal nutrients and antibiotics was used for the isolation of Streptomyces. Starch casein agar (SCA) containing soluble starch 10 gL-1, casein 0.3 gL-1, KNO3 2.0 gL-1, MgSO4·7H2O 0.05 gL-1, K2HPO4 2.0 gL-1, NaCl 2.0 gL-1, CaCO3 0.02 gL-1, FeSO4·7H2O 0.01 gL-1 and Agar 20.0 gL-1 supplemented with cycloheximide (50 mg/L), nystatin (50 mg/L) and rifampicin (50 mg/L) was used as the selective media (Nolan and Cross, 1988). The pH of the media was adjusted to 7. Standard serial dilution and plating method was followed to isolate Streptomyces. Aliquots (100 µL) of dilutions, 1/1000 and 1/10000 were plated on the selective media and incubated at 30 ± 1 °C for 7–10 days. Plates were observed regularly for the growth of the actinomycetes population. Different morphotypes from each of the samples were picked and purified in the selective media. The isolates were then stored as glycerol stocks (20 %) at −80 °C and slants at 4 °C until further study.

2.3 DNA isolation and 16S rRNA gene sequence amplification

Total DNA was extracted from fully grown actinomycetes cultures using Nucleo-pore gDNA Fungal Bacterial Mini Kit employing the manufacturer’s protocol. The quality of DNA was checked and ensured both by gel electrophoresis and nanodrop. Universal primers pA (AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG) and pH (AAGGAGGTGATCCAGCCGCA) were used for the amplification of the 16S rRNA gene. The PCR reactions were carried out in a peqSTAR thermal cycler by following the protocols of Kumar et al. (2014) with slight modifications. Briefly, the reactions were carried out in 25 μL volume comprising 12.5 μL Go Taq green Master Mix 2X (Promega, USA), 100 ng of primers (pA and pH), 50 ng DNA template and nuclease free water to adjust the volume. PCR conditions used were as follows; initial denaturation-95 °C for 5 min followed by 35 cycles of denaturation-95 °C for 30 s, annealing-52 °C for 40 s and extension-72 °C for 60 s; and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. The amplified PCR products were visualized in 1.5 % agarose gel electrophoresis (stained with ethidium bromide) using a gel documentation system (Bio Rad, USA).

2.4 16S rRNA gene sequencing and phylogenetic analysis

PCR products were purified using Gene JET PCR Purification Kit (Thermo Fisher, USA) and sequenced using the primer 1100R (GGGTTGCGCTCGTTG) (Engelbrektson et al., 2010) at GeneMatrix sequencing facility by following sanger dideoxy sequencing method in an ABI 3130xl Genetic Analyzer. Resultant sequences were then quality filtered in FinchTV and trimmed for better quality sequences (Stucky, 2012). Quality ensured sequences were then used to run a BLAST search against 16S rRNA gene sequences of type species available in EZ Biocloud to identify the isolates (https://www.ezbiocloud.net). Sequences were aligned and compared using the multiple sequence alignment tool, CLUSTAL W and a phylogenetic tree was constructed employing the neighbour joining method (Saitou and Nei, 1987). The Program used for phylogenetic tree construction is MEGA X (Kumar et al., 2018).

2.5 Characterization of soil actinomycetes based on pigment formation, growth pattern and mycelium formation

Cultural characteristics of all the actinomycete isolates were examined on four different ISP (International Streptomyces Project) media viz., ISP1, 2, 3 and 7, incubated at 28 ± 2 °C for 14 days. Morphological characteristics like pigment formation, growth pattern (recorded under three categories viz., poor, moderate and Good) and the colour of aerial and substrate mycelium were recorded.

2.6 Antifungal activity against phytopathogenic fungi

Four phytopathogenic fungi viz., Fusarium udum (NAIMCC-F-02017), Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceris (NAIMCC-F-00889), Macrophomina phaseolina (NAIMCC-F-01260) and Sclerotium rolfsii (NAIMCC-F-01638) were collected from NAIMCC. They were grown on potato dextrose agar plates with an incubation at 28 ± 2 °C for 24–120 h and maintained on PDA slants and mineral oil for further use. Freshly grown cultures were used for antifungal assays. A dual culture assay was employed to test the antagonistic activity of Streptomyces spp. against four selected phytopathogens. SCA and PDA in the ratio of 1:1 was used as a medium to test the antagonistic activity. Fresh cultures of the bacterium were inoculated on two sides of the plate with the selected medium. The centre of the plate was inoculated with fresh mycelium of the test pathogens and the plates were incubated at 28 ± 2 °C for 96 h. Plates were observed twice a day during incubation for inhibition zones. Plates inoculated with test pathogen alone were also incubated simultaneously as a control. The zone of inhibition and percent inhibition of fungi were calculated using the following formula. where F = radius of fungal growth from the centre (cm) in the control plate.

A = the radius of radial fungal growth from the centre (cm) in the dual culture plate.

3 Results

3.1 Actinomycetes community composition

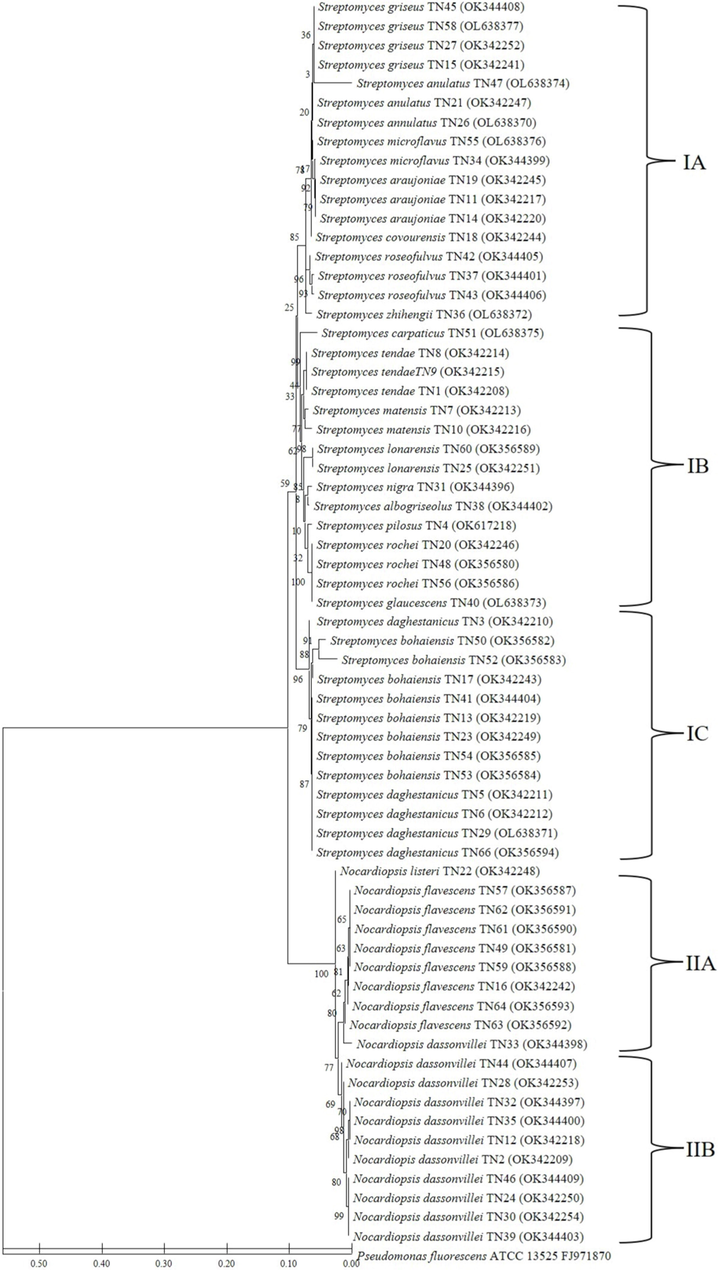

Isolation on the selective media resulted in a total of sixty-five isolates from 40 samples collected from Tamil Nadu (Table 1). Identification based on 16S rRNA gene sequencing and blast search against type species database revealed that these 65 isolates were affiliated to two genera belonging to Streptomyces and Nocardiopsis (Fig. 1).

Neighbour-joining phylogenetic tree based on 16S rRNA gene sequences showing the relationship between the 45 Streptomyces and 20 Nocardiopsis strains. Bootstrap value based on 1000 resampled datasets are shown at branch nodes.

3.2 Streptomyces

The genus Streptomyces represents 45 isolates accounting for 67.69 % of the total isolates. It was represented by 18 species viz., S griseus (4), S. anulatus (3), S. microflavus (2), S. covourensis (1), S.araujoniae (3), S. zhihengii (1), S. roseofulvus (3), S. daghestanicus (5), S. carpaticus (1), S. matensis (2), S. glaucescens (1), S. tendae (3), S. nigra (1), S. albogriseolus (1), S. pilosus (1), S. rochei (3), S. bohaiensis (8), S. lonarensis (2).

3.3 Nocardiopsis

Identified isolates include Nocardiopsis representing 32.31 % of the total isolates. Isolates belonging to Nocardiopsis are not as diverse as Streptomyces representing only three species viz., Nocardiopsis dassonvillei (11), Nocardiopsis flavescens (8) and Nocardiopsis listeria (1).

3.4 Phylogenetic diversity of actinomycetes based on 16S rRNA gene sequences

The relationship between the two genera obtained in the present study demonstrated through a phylogenetic tree is presented in Fig. 1. All the 65 strains were grouped into two genera Streptomyces and Nocardiopsis; the upper side of the dendrogram representing Streptomyces with 18 species, S. griseus, S. anulatus, S. microflavus, S. covourensis, S. araujoniae, S. zhihengii, S. roseofulvus, S. daghestanicus, S. carpaticus, S. matensis, S. glaucescens, S. tendae, S. nigra, S. albogriseolus, S. pilosus, S. rochei, S. bohaiensis and S. lonarensis. Streptomyces griseus, S. anulatus, S. microflavus and S. araujoniae separate in sub cluster 1A; Streptomyces griseus showed more close similarity with S. anulatus. Streptomyces covourensis, S. zhihengii, S. carpaticus, S. matensis, S. glaucescens, S. nigra, S. albogriseolus, and S. pilosus, were represented by single nodes which separate in different sub cluster. The larger cluster was represented by Streptomyces bohaiensis which separates in subcluster 1C, which is also represented by S. daghestanicus. Major cluster 2 is represented by the genus Nocardiopsis and it has been divided into two sub clusters, 2A and 2B. Sub cluster 2A presents all Nocardiopsis flavescens and single node Nocardiopsis listeria while sub cluster 2B represents all Nocardiopsis dassonvillei.

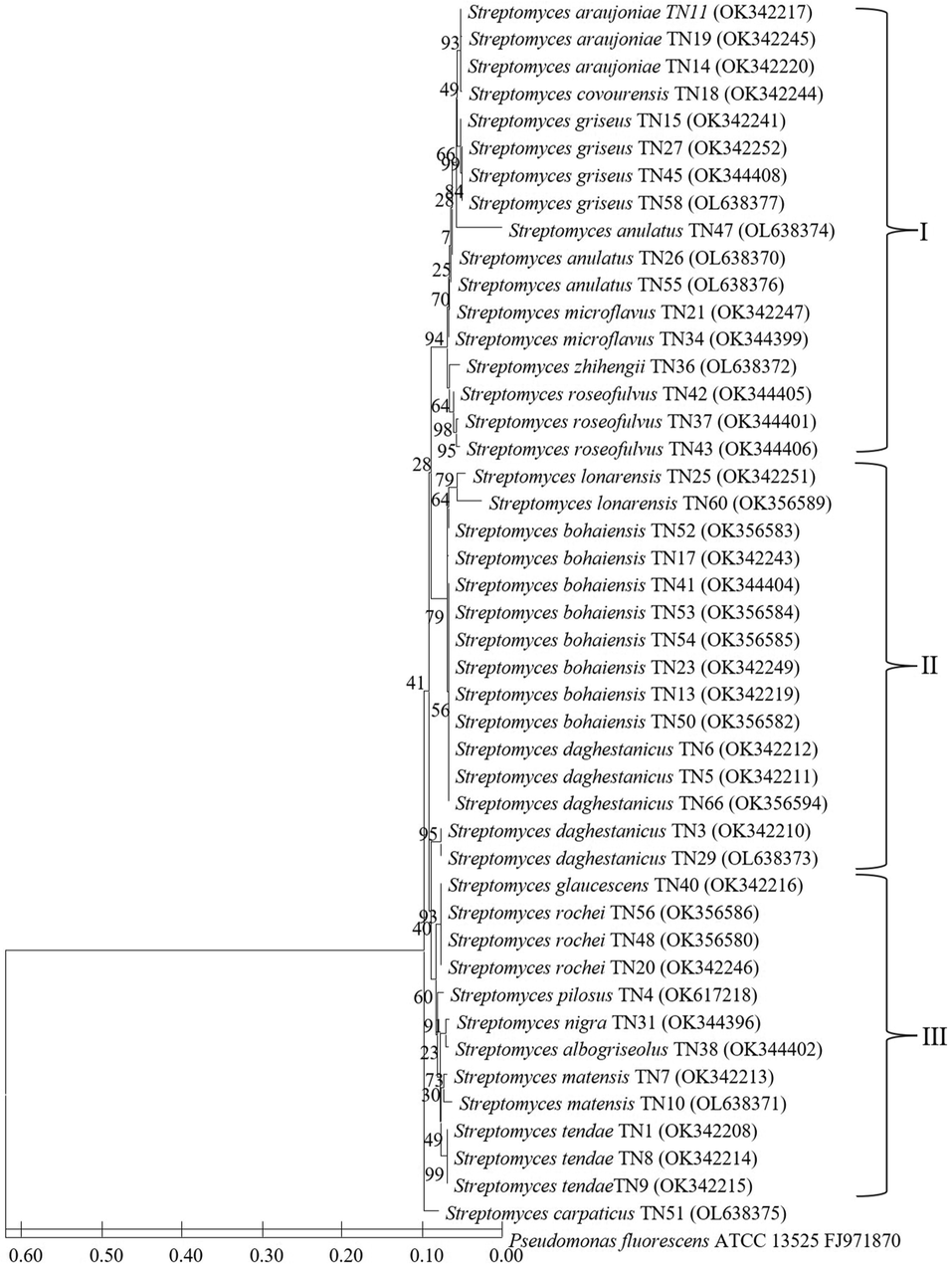

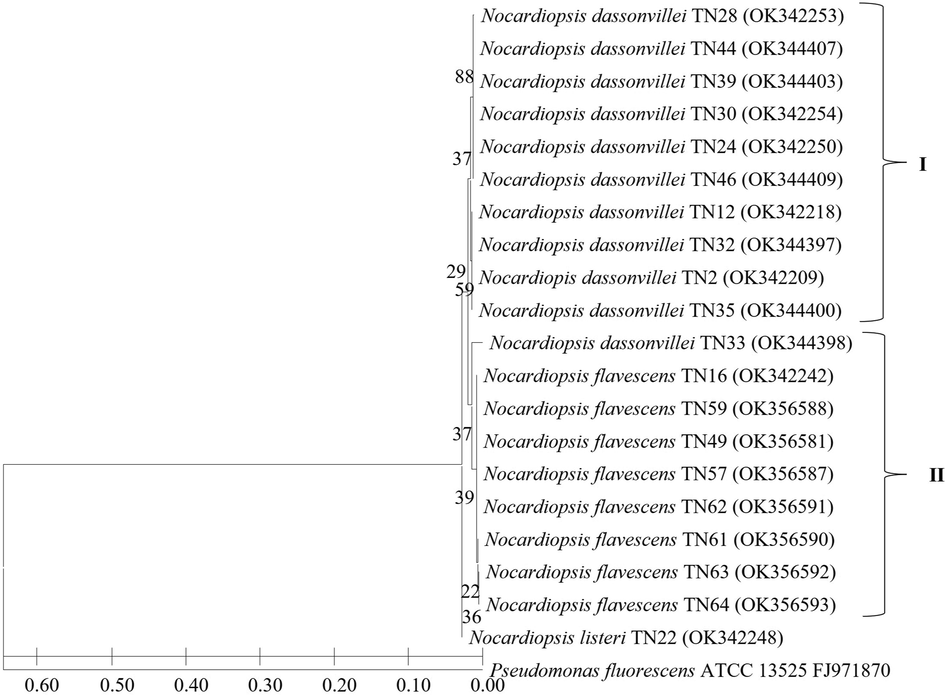

The phylogenetic tree presenting the relationship among the 45 strains of the genus Streptomyces is presented in Fig. 2. It showed the grouping of sequences into three distinct groups I, II, and III. Group I present a maximum of 17 Streptomyces strains; all three strains of S.araujoniae isolated from three different crop fields which showed 99 % sequence similarity formed a distinct branch in this group. Similarly, in this group S. griseus, S. anulatus, S. microflavus and S. roseofulvus forms separate cluster; these were isolated from different crop fields and showed more than 99 % sequence similarities. One strain of S. covourensis and S. zhihengii in cluster I were collected from the rice rhizosphere. Two strains of S. lonarensis separated in cluster II which showed 99–100 % similarity with respective species and were collected from rice and maize rhizosphere. Interestingly major cluster II comprises 15 strains separated into three subclusters, with a maximum of eight strains that belong to S. bohaiensis, followed by S. daghestanicus. Cluster III presents five species with single isolates of each which includes S. glaucescens, S. pilosus, S. nigra, S. albogriseolus and S. carpaticus; these strains were collected from rice, bulk soil, and grass field as presented in Table 1. Additionally, this cluster also presents 3 strains each of S. rochei and S. tendae; all these six strains were isolated from six different crop fields. Fig. 3 presents the relationship among the members of Nocardiopsis which exhibits the grouping of sequences in two major groups; cluster I comprise a maximum of 10 strains which showed 99–100 % sequence similarities with Nocardiopsis dassonvillei. Out of these 10 strains, seven were isolated from rice rhizosphere, two from coconut fields and one from sorghum rhizosphere. Further cluster II comprises eight strains that showed 99 % sequence similarities with Nocardiopsis flavescens these isolates were from six different crop fields which includes palm, okra, rice, redgram, lemon, and banana. Additionally in this cluster, 1 strain showed 99 % sequence similarities with Nocardiopsis listeri isolated from rice rhizosphere grouped as a separate subgroup.

Neighbour-joining phylogenetic tree based on 16S rRNA gene sequences showing the relationship among the 45 Streptomyces strains. Bootstrap value based on 1000 resampled datasets are shown at branch nodes.

Neighbour-joining phylogenetic tree based on 16S rRNA gene sequences showing the relationship among the 20 Nocardiopsis strains. Bootstrap value based on 1000 resampled datasets are shown at branch nodes.

3.5 Morphological characteristics of actinomycetes

The morphological properties of all 65 actinomycetes strains are presented in Supplementary Table 1. The strains showed differential growth patterns on different ISP media. Six strains viz., S. daghestanicus TN6, S. araujoniae TN14, N. flavescens TN14, S.bohaiensis TN17, S. griseus TN27 and N. dassonvillei TN33 were characterized as showing good growth in all the four ISP media. Twenty-one strains were characterized as showing good growth in atleast three ISP media while seventeen strains showed good growth in atleast two ISP media. Pigment production was observed in twenty strains in atleast one media. S. zhihengii TN 36 produced pigment on all four ISP media and S. araujoniae TN19 produced pigments on three ISP media while the strains S. araujoniae TN11, S. araunoniae TN14 and S. anulatus TN55 produced pigments on atleast two ISP media. The Media ISP-3 facilitated the production of pigment by 18 strains TN1, TN3, TN6, TN8, TN9, T11, TN13, TN14, TN16, TN17, TN19, TN28, TN31, TN35, TN38, TN55, TN63, and TN66; Six strains which include TN1, TN8, TN9, TN11, TN19, and TN28, exhibit pigment formation on ISP-1 media. Five strains showed pigmentation on ISP-4 media which includes TN4, TN5, TN9, TN14, and TN19 while ISP-7 facilitated pigment formation by only one strain (TN9). The colour of aerial and substrate mycelium of all the 65 actinomycetes strains was also recorded which includes white, brown, pale green, pale yellow, yellow, grey, greenish-yellow, light green, green, light yellow and dark green.

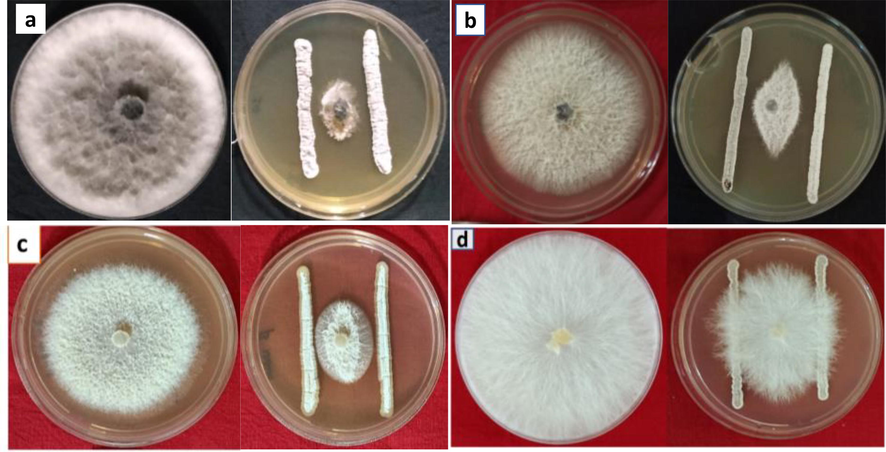

3.6 Antifungal activity of actinomycetes strains

Antifungal activities of all the 65 actinomycetes strains against four fungal strains, F. udum, F. oxysporum f.sp. ciceris, M. phaseolina and S. rolfsii. are represented in Table 3. All 65 strains showed antifungal activity against F. udum with inhibition ranging from 1.96 to 63.99 %. S. daghestanicus TN3, N. dassonvillei TN12 and S. araujoniae TN19 showed maximum inhibition with respective inhibition percentages of 63.99, 63.96 and 63.96. Twenty strains showed more than 50 % inhibition against F. udum. Similarly, all the strains exhibited antifungal activity against F. oxysporum f.sp. ciceris with inhibition ranging from 1.79 to 63.81 %. Nine strains showed more than 50 % inhibition against F. oxysporum while strains S. araujoniae TN11 and S. daghestanicus TN3 showed maximum inhibition with a percent inhibition of 63.81 and 61.33, respectively. Out of 65 strains, 48 showed the ability to inhibit Macrophomina phaseolina on plates with inhibitions ranging from 3.75 to 82.50 %. Twenty strains in the study have shown inhibition percent of 70 and above against M. phaseolina while strains S. rochei TN56, N. flavescens TN49 and S. daghestanicus TN 66 showed maximum inhibitions with percent inhibitions of 82.50, 81.67 and 79.17 respectively. Against S. rolfsii 39 strains showed inhibition and inhibition percent was recorded between 3.33 and 52.50. Only three strains viz., S. araujoniae TN11, S. araujoniae TN19 and S. griseus TN27 showed more than 40 % inhibition. A total of 27 strains showed antifungal activity against all four fungal strains, with six strains viz., S. pilosus TN4 (Fig. 4), S. tendae TN8, S. araujoniae TN11, N. dassonvillei TN12 S. araujoniae TN19 and S. griseus TN27 showing considerable percent inhibition against all the four pathogens tested, while 33 strain showed antifungal activity against atleast three fungal strains.

Antifungal activity of Streptomyces pilosus TN4 against different fungal pathogens; Macrophomina phaseolina (a), Fusarium oxysporum (b), Fusarium udum (c) and Sclerotium rolfsii (d).

3.7 Nucleotide sequence accession numbers

The 16S rRNA gene sequences of 65 strains identified in the current study have been submitted to the GenBank nucleotide sequence database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nucleotide). All the strains isolated and characterized in this study were submitted to NAIMCC (National Agriculturally Important Microbial Culture Collection, ICAR-NBAIM, India (Table 2).

Strain No

Identity

NAIMCC accession number

NCBI accession number

TN1

Streptomyces tendae

NAIMCC-B-02880

OK342208

TN2

Nocardiopis dassonvillei

NAIMCC-B-02865

OK342209

TN3

Streptomyces daghestanicus

NAIMCC-B-02874

OK342210

TN4

Streptomyces pilosus

NAIMCC-B-03007

OK617218

TN5

Streptomyces daghestanicus

NAIMCC-B-02875

OK342211

TN6

Streptomyces daghestanicus

NAIMCC-B-02876

OK342212

TN7

Streptomyces matensis

NAIMCC-B-02878

OK342213

TN8

Streptomyces tendae

NAIMCC-B-02881

OK342214

TN9

Streptomyces tendae

NAIMCC-B-02882

OK342215

TN10

Streptomyces matensis

NAIMCC-B-02879

OK342216

TN11

Streptomyces araujoniae

NAIMCC-B-02868

OK342217

TN12

Nocardiopsis dassonvillei

NAIMCC-B-02866

OK342218

TN13

“Streptomyces bohaiensis

NAIMCC-B-02871

OK342219

TN14

Streptomyces araujoniae

NAIMCC-B-02869

OK342220

TN15

Streptomyces griseus

NAIMCC-B-02877

OK342241

TN16

Nocardiopsis flavescens

NAIMCC-B-02867

OK342242

TN17

Streptomyces bohaiensis

NAIMCC-B-02872

OK342243

TN18

Streptomyces covourensis

NAIMCC-B-02873

OK342244

TN19

Streptomyces araujoniae

NAIMCC-B-02870

OK342245

TN20

Streptomyces rochei

NAIMCC-B-02904

OK342246

TN21

Streptomyces microflavus

NAIMCC-B-02901

OK342247

TN22

Nocardiopsis listeri

NAIMCC-B-02908

OK342248

TN23

Streptomyces bohaiensis

NAIMCC-B-02897

OK342249

TN24

Nocardiopsis dassonvillei

NAIMCC-B-02889

OK342250

TN25

Streptomyces lonarensis

NAIMCC-B-02900

OK342251

TN26

Streptomyces anulatus

NAIMCC-B-02894

OL638370

TN27

Streptomyces griseus

NAIMCC-B-02899

OK342252

TN28

Nocardiopsis dassonvillei

NAIMCC-B-02890

OK342253

TN29

Streptomyces daghestanicus

NAIMCC-B-03002

OL638371

TN30

Nocardiopsis dassonvillei

NAIMCC-B-02891

OK342254

TN31

Steptomyces nigra

NAIMCC-B-02903

OK344396

TN32

Nocardiopsis dassonvillei

NAIMCC-B-02892

OK344397

TN33

Nocardiopsis dassonvillei

NAIMCC-B-02893

OK344398

TN34

Streptomyces microflavus

NAIMCC-B-02902

OK344399

TN35

Nocardiopsis dassonvillei

NAIMCC-B-02894

OK344400

TN36

Streptomyces zhihengii

NAIMCC-B-03010

OL638372

TN37

Streptomyces roseofulvus

NAIMCC-B-02905

OK344401

TN38

Streptomyces albogriseolus

NAIMCC-B-02896

OK344402

TN39

Nocardiopsis dassonvillei

NAIMCC-B-02895

OK344403

TN40

Streptomyces glaucescens

NAIMCC-B-03003

OL638373

TN41

Streptomyces bohaiensis

NAIMCC-B-02898

OK344404

TN42

Streptomyces roseofulvus

NAIMCC-B-02906

OK344405

TN43

Streptomyces roseofulvus

NAIMCC-B-02907

OK344406

TN44

Nocardiopsis dassonvillei

NAIMCC-B-02985

OK344407

TN45

Streptomyces griseus

NAIMCC-B-03004

OK344408

TN46

Nocardiopsis dassonvillei

NAIMCC-B-02986

OK344409

TN47

Streptomyces anulatus

NAIMCC-B-02995

OL638374

TN48

Streptomyces rochei

NAIMCC-B-03008

OK356580

TN49

Nocardiopsis flavescens

NAIMCC-B-02992

OK356581

TN50

Streptomyces bohaiensis

NAIMCC-B-02997

OK356582

TN51

Streptomyces carpaticus

NAIMCC-B-03001

OL638375

TN52

Streptomyces bohaiensis

NAIMCC-B-02998

OK356583

TN53

Streptomyces bohaiensis

NAIMCC-B-02999

OK356584

TN54

Streptomyces bohaiensis

NAIMCC-B-03000

OK356585

TN55

Streptomyces anulatus

NAIMCC-B-02996

OL638376

TN56

Streptomyces rochei

NAIMCC-B-03009

OK356586

TN57

Nocardiopsis flavescens

NAIMCC-B-02987

OK356587

TN58

Streptomyces griseus

NAIMCC-B-03005

OL638377

TN59

Nocardiopsis flavescens

NAIMCC-B-02988

OK356588

TN60

Streptomyces lonarensis

NAIMCC-B-03006

OK356589

TN61

Nocardiopsis flavescens

NAIMCC-B-02989

OK356590

TN62

Nocardiopsis flavescens

NAIMCC-B-02990

OK356591

TN63

Nocardiopsis flavescens

NAIMCC-B-02991

OK356592

TN64

Nocardiopsis flavescens

NAIMCC-B-02993

OK356593

TN66

Streptomyces daghestanicus

*Submitted to NAIMCC

OK356594

Strain

F. udum

F. oxysporum

Macrophomina phaseolina

S. rolfsii

TN1

51.04 ± 9.11

12.50 ± 0.634

40.00 ± 2.04

14.17 ± 0.393

TN2

52.02 ± 1.89

42.38 ± 2.36

71.67 ± 3.12

20.83 ± 1.42

TN3

63.99 ± 2.53

61.33 ± 2.20

63.33 ± 3.12

0.00

TN4

49.05 ± 4.28

51.79 ± 3.78

75.00 ± 4.08

38.33 ± 2.47

TN5

29.03 ± 3.06

5.36 ± 0.186

0.00

21.67 ± 1.57

TN6

1.96 ± 0.080

8.93 ± 0.493

16.25 ± 2.04

0.00

TN7

42.01 ± 2.54

41.71 ± 6.88

45.00 ± 3.06

4.17 ± 0.393

TN8

47.98 ± 3.98

42.05 ± 4.37

47.50 ± 2.04

38.33 ± 5.96

TN9

57.99 ± 4.98

12.50 ± 0.892

23.75 ± 1.02

15.83 ± 1.44

TN10

37.05 ± 4.14

56.95 ± 3.15

71.67 ± 3.12

0.00

TN11

62.03 ± 3.36

63.81 ± 4.38

75.00 ± 4.25

52.50 ± 6.29

TN12

63.96 ± 2.88

49.81 ± 2.69

76.67 ± 4.38

36.67 ± 2.33

TN13

10.01 ± 1.02

5.90 ± 0.224

0.00

0.00

TN14

59.00 ± 3.71

53.57 ± 2.92

74.17 ± 2.36

0.00

TN15

6.98 ± 0.322

5.36 ± 0.148

0.00

0.00

TN16

29.03 ± 3.06

32.62 ± 2.36

32.50 ± 2.04

0.00

TN17

57.96 ± 2.96

46.14 ± 3.27

77.50 ± 4.78

15.00 ± 1.02

TN18

13.01 ± 1.09

37.14 ± 5.31

75.00 ± 3.88

0.00

TN19

63.96 ± 2.88

53.57 ± 3.79

78.75 ± 8.66

44.17 ± 2.85

TN20

50.98 ± 3.96

16.07 ± 0.835

0.00

0.00

TN21

5.98 ± 0.072

4.52 ± 0.124

67.50 ± 5.10

7.50 ± 0.282

TN22

16.04 ± 1.03

23.21 ± 1.86

31.25 ± 2.04

11.67 ± 0.632

TN23

10.01 ± 0.672

20.21 ± 2.77

60.83 ± 5.62

0.00

TN24

51.99 ± 2.56

22.43 ± 1.59

65.42 ± 2.36

12.50 ± 0.552

TN25

36.99 ± 2.63

21.43 ± 1.08

10.00 ± 1.32

0.00

TN26

7.01 ± 0.470

43.10 ± 2.63

0.00

10.83 ± 0.447

TN27

35.23 ± 2.71

45.81 ± 3.70

72.50 ± 6.42

44.17 ± 3.88

TN28

48.93 ± 2.98

46.14 ± 3.27

0.00

25.00 ± 1.65

TN29

1.99 ± 0.090

42.38 ± 2.36

3.75 ± 0.18

10.00 ± 0.435

TN30

3.95 ± 0.230

42.43 ± 3.45

70.00 ± 4.08

10.00 ± 0.242

TN31

46.94 ± 5.64

37.50 ± 2.69

45.00 ± 2.04

0.83 ± 0

TN32

6.98 ± 0.19

46.43 ± 2.92

75.00 ± 6.62

0.00

TN33

5.02 ± 0.185

42.38 ± 2.36

0.00

12.50 ± 0.752

TN34

37.82 ± 2.88

47.10 ± 3.76

65.83 ± 3.12

0.00

TN35

6.98 ± 0.183

50.81 ± 3.95

76.67 ± 5.32

11.67 ± 0.668

TN36

7.01 ± 0.292

8.93 ± 0.672

0.00

8.33 ± 0.244

TN37

7.01 ± 0.578

32.62 ± 2.36

0.00

8.33 ± 0.435

TN38

53.00 ± 4.24

46.14 ± 3.27

66.67 ± 5.65

24.17 ± 1.18

TN39

56.00 ± 3.71

47.00 ± 4.24

0.00

11.67 ± 0.662

TN40

6.98 ± 0.468

32.14 ± 2.92

0.00

10.83 ± 0.543

TN41

4.99 ± 0.178

11.67 ± 0.578

70.00 ± 2.88

0.00

TN42

8.02 ± 0.541

12.50 ± 0.449

0.00

12.50 ± 0.652

TN43

11.02 ± 0.672

9.29 ± 0.326

0.00

5.83 ± 0.432

TN44

6.98 ± 0.135

8.93 ± 0.552

0.00

20.83 ± 1.88

TN45

6.00 ± 0.224

10.71 ± 0.637

77.50 ± 7.72

14.17 ± 0.542

TN46

57.99 ± 2.54

41.07 ± 2.89

73.33 ± 5.36

0.00

TN47

8.02 ± 0.376

8.93 ± 0.472

38.75 ± 2.76

0.00

TN48

57.99 ± 2.54

42.71 ± 2.74

70.83 ± 7.32

17.50 ± 1.12

TN49

59.98 ± 3.92

50.19 ± 2.69

81.67 ± 9.12

0.00

TN50

10.99 ± 1.08

5.36 ± 0.154

67.50 ± 1.98

0.00

TN51

1.96 ± 0.073

8.93 ± 0.438

0.00

0.00

TN52

6.00 ± 0.080

1.79 ± 0.052

0.00

0.00

TN53

2.97 ± 0.240

12.50 ± 0.472

40.00 ± 2.66

10.83 ± 0.242

TN54

44.98 ± 1.92

46.76 ± 3.33

74.17 ± 4.65

0.00

TN55

60.01 ± 2.84

48.67 ± 5.79

75.83 ± 8.44

5.00 ± 0.680

TN56

57.96 ± 2.96

47.14 ± 2.10

82.50 ± 6.35

0.00

TN57

1.96 ± 0.177

8.93 ± 0.558

64.17 ± 5.42

3.33 ± 0.182

TN58

3.98 ± 0.134

12.50 ± 0.738

6.25 ± 0.252

0.00

TN59

4.96 ± 0.273

16.07 ± 1.19

67.50 ± 3.44

5.00 ± 0.152

TN60

6.00 ± 0.082

8.93 ± 0.662

65.00 ± 5.88

12.50 ± 0.822

TN61

7.93 ± 0.495

5.36 ± 0.293

40.00 ± 3.77

10.00 ± 0.680

TN62

56.16 ± 3.52

8.93 ± 0.548

47.50 ± 4.29

0.00

TN63

7.96 ± 0.269

8.93 ± 0.437

0.00

9.17 ± 0.393

TN64

9.95 ± 0.358

23.21 ± 1.79

67.50 ± 5.32

0.00

TN66

63.09 ± 3.96

55.76 ± 3.51

79.17 ± 7.98

14.17 ± 1.35

4 Discussion

Actinomycetes are endowed with metabolic potential to survive and prosper in varied environments including agricultural fields where their presence impacts the survival and growth of other bacteria, as well as plants (Verma et al., 2011; Sadeghi et al., 2012; Bennur et al., 2016; Olanrewaju and Babalola, 2019; Ma et al., 2020). Among the actinomycetes, the genus Streptomyces is endowed with a plethora of metabolic capabilities and hence considered as bacteria of immense importance both in natural environments and Industry. To explore the potential of this group of bacteria it is necessary to understand their diversity, physiology, and ecology (Ma et al., 2020). The aim of this study was to specifically isolate Streptomyces and study their genetic and cultural diversity and explore their antifungal potential against various phytopathogens. A selective media was used to isolate Streptomyces spp. from crops’ rhizosphere and bulk soil collected from different fields and different regions of Tamil Nadu, India. A total of 65 putative Streptomyces isolates were collected, characterized, and identified. Identification based on 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity revealed the isolates fall under two genera viz., Streptomyces and Nocardiopsis. It's worth noting that the 16S rRNA gene sequence's utility as a phylogenetic and taxonomy identifier is restricted. The core genome divergence between Streptomyces strains with 97 percent 16S rRNA gene sequence identity can be as high as 30 %, with an ANI of 100–78.3 % (van Bergeijk et al., 2020). 16S rRNA gene sequence identity of 98.6 % is widely used for bacterial species identification and delineation (Chun et al., 2018); however, for actinomycetes, this threshold is raised to 99 % based on comparative studies between 16S rRNA gene sequences (Guo et al., 2015). As a result, we used a 99–100 % threshold to assign actinomycetes isolates to distinct clusters. Since more than 30 % of the isolates obtained in the study belonged to Nocordiopsis we have taken those isolates too in further analysis. Like Streptomyces spp. members of the genus Nocardiopsis too can survive under different environmental conditions and produce a range of bioactive compounds (Bennur et al., 2016). In the current study, 45 isolates were assigned to Streptomyces spp., and 20 isolates to Nocardiopsis spp. based on 16S rRNA gene sequences. Streptomyces spp. is reported to have advanced adaptability to exist in different extreme environments and habitant of diverse conditions like frozen soils, deserts, and oceans (Okoro et al., 2009; Passari et al., 2018). The findings of this study have shown that there is a high level of diversity within Streptomyces spp. present in the agriculture fields of Tamil Nadu. The isolates collected from different crop rhizosphere and bulk soils of agriculture fields fell under 18 species forming three clades. A similar study on the diversity of streptomycetes in prairie soils resulted in 34 different OTUs, albeit the 16S rRNA gene sequence used for diversity analysis is less than 300 bp in the study (Davelos et al., 2004). In our earlier study with soils of Meghalaya, India the diversity of Streptomyces spp. is higher representing 26 different species (Singh et al., 2022).

Streptomyces bohaiensis is the most abundant (8 isolates) among the 45 Streptomyces spp. isolates found in the rhizosphere of rice, okra, brinjal and chilli and in bulk soil, while S. daghestanicus is the second most abundant isolate (5 isolates). A study earlier has shown the presence of Streptomyces spp. in 20 different plant communities (Adil et al., 2017). In the present study, we have isolated Streptomyces spp. from 34 samples among the 40, representing rhizosphere of different crops like rice, maize, sorghum, groundnut, sunflower, castor, brinjal, okra and chilli, bulk soils of coconut, jatropha and palm fields, thus confirming their ubiquity in soils. Cultural characterization on different ISP media is a routine study involved in the characterization of actinomycetes. In our study, cultural characterization on four different ISP media has shown immense diversity among the soil actinomycetes. Isolates belonging to the same species gave different characterizations among themselves reiterating the fact that there are strain level differences. More than twenty strains showed pigment production in various ISP media used. Earlier many researchers reported similar pigmentation by different actinomycetes strains (Fernandes et al., 2021; Amsaveni et al., 2015).

Antifungal activity of actinomycetes especially, Streptomyces spp. are reported in various studies (Rey and Dumas, 2017; Tamreihao et al., 2018; Marimuthu et al., 2020; Sholkamy et al., 2020; Gebily et al., 2021). They have been found to protect a variety of plants from soil-borne fungal diseases to varying degrees. Similarly, the members of the genus Nocardiopsis are known for their antifungal activity against different phytopathogens (Bennur et al., 2016). The inherent problems of resistance development by the target fungi and residue in the environment, associated with disease control measures by chemical fungicides led to the search for alternative plant protection measures. Due to the lack of novel antimicrobial metabolites, more and more researchers are focusing their efforts on different ecosystems. In the present study, antifungal activity assay against four fungal pathogens has shown that all 65 actinomycetes strains showed antifungal activity against both F. udum and F. oxysporum f. sp. ciceris. This is consistent with the results of Amini et al. 2016 who reported all 112 actinobacteria isolated as antifungal against F. oxysporum f.sp. ciceris. In the current study, 74.25 % strain showed antifungal activity against M. phaseolina and 60.60 % against S. rolfsii. Singh et al. (2016) tested the antifungal properties of 80 actinomycetes strains against Rhizoctonia solani, Fusarium solani, Macrophomina phaseolina, Sclerotium rolfsii, and Colletotrichum truncatum, and found various level of antifungal properties of different strains. Kamara and Gangwar (2015) isolated 100 actinomycetes strains from 30 rhizospheric soil samples of Catharanthus roseus and Withania somnifera from different locations of Ludhiana, India, and tested their antifungal activity against viz: Sclerotium rolfsii, Rhizoctonia solani, Helminthosporium oryzae, Macrophomina phaseolina, Penicillium sp., Fusarium oxysporum and Alternaria alternata. These findings along with our results suggest that rhizospheric soils have the prospective to identify actinomycetes with potent antifungal activity. To the best of our understanding, the present study offers for the first time a prelude about the unexplored streptomycetes and Nocardiposis diversity associated with different crop root rhizosphere and bulk soil from different locations in Tamil Nadu, India.

5 Conclusion

Our findings suggest that there exists a higher level of diversity among the members of the genera Streptomyces and Nocardiopsis in agricultural fields of Tamil Nadu although the latter is less diverse as compared to Streptomyces spp. The study also demonstrates that members of these genera inhabiting the rhizosphere and bulk soils of the study area possess great potential as antifungal agents. Their utilities as biocontrol agents are to be explored in further studies.

Authors contributions

PT, MTZ and SCK performed isolation, morphological characterization, and antifungal activity assay. WAA performed the phylogenetic analysis and compiled the data. MK planned and supervised the experiments and prepared the first draft. HC and AKS collected samples, planned experiments, and improved the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Authors are grateful for Indian Soil Microbiome Project, ICAR-NBAIM, Mau, India, for providing funds required for sample collection and experimentation. Authors also express sincere gratitude to the Director ICAR-NBAIM, for providing infrastructure facility.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Plant community richness mediates inhibitory interactions and resource competition between Streptomyces and Fusarium populations in the rhizosphere. Microbiol. Ecol.. 2017;74:157-167.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of Streptomyces spp. against Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceris for the management of chickpea wilt. J. Plant. Prot. Res.. 2016;56(3):1-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Screening and isolation of pigment producing Actinomycetes from soil samples. J. Biosci. Nanosci. 2015;2(2):24-28.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nocardiopsis species: a potential source of bioactive compounds. J. Appl. Microbiol.. 2016;120(1):1-16.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diversity and versatility of actinomycetes and its role in antibiotic production. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci.. 2013;3(8):S83-S94.

- [Google Scholar]

- Proposed minimal standards for the use of genome data for the taxonomy of prokaryotes. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol.. 2018;68(1):461-466.

- [Google Scholar]

- Spatial variation in Streptomyces genetic composition and diversity in a prairie soil. Microbial Ecol.. 2004;48(4):601-612.

- [Google Scholar]

- Plant growth and resistance promoted by Streptomyces spp. in tomato. Plant Physiol. Biochem.. 2017;118:479-493.

- [Google Scholar]

- Experimental factors affecting PCR-based estimates of microbial species richness and evenness. ISME J.. 2010;4(5):642-647.

- [Google Scholar]

- Isolation and identification of pigment producing actinomycete Saccharomonospora azurea SJCJABS01. Biomed. Pharmacol. J.. 2021;14(4):2261-2269.

- [Google Scholar]

- Characterization and potential antifungal activities of three Streptomyces spp. as biocontrol agents against Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (Lib.) de Bary infecting green bean. Egyptian J. Biol. Pest Control. 2021;31(1):1-15.

- [Google Scholar]

- Red soils harbor diverse culturable actinomycetes that are promising sources of novel secondary metabolites. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.. 2015;81(9):3086-3103.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mechanism of phosphate solubilization and antifungal activity of Streptomyces spp. isolated from wheat roots and rhizosphere and their application in improving plant growth. Microbiol.. 2014;160(4):778-788.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antifungal Activity of Actinomycetes from Rhizospheric Soil of Medicinal plants against phytopathogenic fungi. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci.. 2015;4(3):182-187.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biocontrol and plant growth promoting potential of phylogenetically new Streptomyces sp. MR14 of rhizospheric origin. AMB Express. 2019;9(1):1-14.

- [Google Scholar]

- MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol.. 2018;35:1547-1549.

- [Google Scholar]

- Deciphering the diversity of culturable thermotolerant bacteria from Manikaran hot springs. Annals Microbiol.. 2014;64(2):741-751.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phylogenetic and physiological diversity of cultivable actinomycetes isolated from alpine habitats on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Front. Microbiol. 2020:2218.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antifungal activity of Streptomyces sp. SLR03 against tea fungal plant pathogen Pestalotiopsis theae. J. King Saud Univ. Sci.. 2020;32(8):3258-3264.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diversity of culturable actinomycetes in hyper-arid soils of the Atacama Desert, Chile. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2009;95(2):121-133.

- [Google Scholar]

- Streptomyces: implications and interactions in plant growth promotion. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol.. 2019;103(3):1179-1188.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bioprospection of actinobacteria derived from freshwater sediments for their potential to produce antimicrobial compounds. Microb. Cell Factories. 2018;17(1):1-14.

- [Google Scholar]

- Plenty is no plague: Streptomyces symbiosis with crops. Trends Plant Sci.. 2017;22(1):30-37.

- [Google Scholar]

- Plant growth promoting activity of an auxin and siderophore producing isolate of Streptomyces under saline soil conditions. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol.. 2012;28(4):1503-1509.

- [Google Scholar]

- The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol.. 1987;4(4):406-425.

- [Google Scholar]

- Streptomyces as symbionts: an emerging and widespread theme? FEMS Microbiol. Rev.. 2012;36(4):862-876.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial quercetin 3-O-glucoside derivative isolated from Streptomyces antibioticus strain ess_amA8. J. King Saud Univ. Sci.. 2020;32(3):1838-1844.

- [Google Scholar]

- Genetic Diversity and Anti-Oxidative Potential of Streptomyces spp. Isolated from Unexplored Niches of Meghalaya, India. Curr. Microbiol.. 2022;79(12):379.

- [Google Scholar]

- Characterization of actinomycetes against phytopathogenic fungi of Glycine max. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res.. 2016;9(Suppl 1):216-219.

- [Google Scholar]

- SeqTrace: a graphical tool for rapidly processing DNA sequencing chromatograms. J. Biomol. Tech.. 2012;23(3):90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Isolation and identification of Streptomyces spp. from Venezuelan soils: morphological and biochemical studies. Microbiol. Res.. 2006;161(3):222-231.

- [Google Scholar]

- Acidotolerant Streptomyces sp. MBRL 10 from limestone quarry site showing antagonism against fungal pathogens and growth promotion in rice plants. J. King Saud Univ. Sci.. 2018;30(2):143-152.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ecology and genomics of Actinobacteria: new concepts for natural product discovery. Nat. Rev. Microbiol.. 2020;18(10):546-558.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bio-control and plant growth promotion potential of siderophore producing endophytic Streptomyces from Azadirachta indica A. Juss. J. Basic Microbiol.. 2011;51(5):550-556.

- [Google Scholar]

Appendix A

Supplementary material

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2023.102619.

Appendix A

Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article: