Translate this page into:

Dissolution of clotted blood from slaughtered cattle by alkaline protease produced by Streptomyces violaceoruber isolated from saline soil in Saudi Arabia

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Saudi Arabia suffers from the spread of diseases linked to clotted blood leaking from slaughtered livestock. Anticoagulant proteases produced by Streptomyces are used to safely dissolve clotted blood. Halophilic Streptomyces isolates were extracted from saline soil in Saudi Arabia and tested to dissolve clotted blood by protease. The most protease-producing isolate was identified using classical and genetic methods. The protease was precipitated with saturated ammonium sulfate from a batch of blood clots inoculated with the most protease-producing isolates. Streptomyces isolates (410) were recovered from thirty saline soil samples collected from Dammam (170 isolates, 41.4 %), Al-Khobar (126 isolates, 30.8 %) and Al-Ahsa (114 isolates, 27.8 %). Proteolytic activity was observed in 305 isolates including the most protease-producing isolate S295, which showed the highest activity (33.8 mm), and was identified as S. violaceoruber (99 % similarity). Among all isolates, 241 showed partial hemolysis (alpha) and 64 showed complete hemolysis (beta), including isolate S295 that presented the highest hemolytic activity (0.58 %). The alkaline protease was precipitated with saturated ammonium sulfate (60 %), and it was found that its activity was 5.2 U/ml, total activity 24,960 U/ml, specific activity 463 U/mg, purification fold 15.2 and yield 78 %. The purified alkaline protease was electrophoresed as a single band at 45 kDa.

Keywords

Alkaline protease

Anticoagulants

Fibrinolytic enzymes

Streptomyces

- MRSA

-

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

- BLV

-

Bovine leukemia virus

- RNA

-

Ribonucleic acid

- PCR

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- BLAST

-

Basic local alignment search tool

- RBCs

-

Red blood cells

- UV–visible

-

Ultraviolet visible

- rpm

-

Rotation per minute

- CFU

-

Colony forming unit

- PAGE

-

Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- SDS

-

Sodium dodecyl sulfate

- DAP

-

Diaminopimelic acid

- ISP

-

International Streptomyces project

- kDa

-

Kilo dalton

Abbreviations

1 Introduction

During the slaughter of livestock and blood transfusion, the blood coagulates, because fibrinogen is oxidized in the air into fibrin fibers. Clotted blood poses a major problem, as pathogenic bacteria grow and spread, causing serious diseases. Therefore, dissolving clotted blood is an essential biotechnological approach to prevent the proliferation of pathogenic bacteria and the spread of related diseases. Anticoagulant proteases are produced by various microbes, including actinomycetes, especially Streptomyces that effectively dissolve clotted blood in a safe and hygienic manner (Kearney et al., 2022). Protease is the first line of anticoagulation even before heparin and its derivatives, because it directly dissolves blood clots in a short time (Farwa et al., 2021). Leaving or improperly disposing of clotted blood leads to overgrowth of pathogenic bacteria and outbreaks of infectious diseases. Moreover, the slaughter of sick livestock suffering from septicemia leads to the spread of zoonotic diseases, especially if the blood is not treated (Gummow, 2023). Clotted blood is usually associated with chronic diseases that aren't diagnosed during examination (Rustem and John, 2023). Escherichia coli and Mycobacterium paratuberculosis as Gram-negative bacteria and Bacillus anthracis and MRSA as Gram-positive bacteria are the most common pathogenic bacteria associated with untreated clotted blood. Cloning of the encoded gene in E. coli through ideal environmental conditions led to large-scale production on a large industrial scale (Chitte et al., 2011). Untreated clotted blood contaminated with BLV leads to transmission of infection to animals and humans, causing leukemia in livestock and breast and lung cancer in humans (Gertrude et al., 2019).

Proteases are usually the first anticoagulants among fibrinolytic enzymes, because they do not cause adverse effects, such as bleeding, immunostimulants, and are expensive (Asha et al., 2022). Other fibrinolytic enzymes degrade fibrin fibers either indirectly such as urokinase or directly such as lumbrokinase (Nakae et al., 2022). S. rimosus produces a peak of fibrinolytic enzymes within three days and declines with a prolonged period (Rui et al., 2019). S. megasporus produces a thermostable actinokinase that remains active over a wide pH range and dissolves blood clots in a short time. Hence, proteases are of great importance in the medical field, because they are used as powerful anticoagulants, which effectively prevent or treat cardiovascular diseases which are the primary cause of blood clots (Yusuf et al., 2020). This study aims to dissolve clotted blood from slaughtered cattle using the alkaline protease produced by Streptomyces as one of the effective fibrinolytic enzymes.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Soil sampling

Dammam, Al-Khobar and Al-Ahsa in Saudi Arabia were targeted as saline areas, where 30 soil samples were collected. The surface layer of soil was removed and the soil sample was taken to a depth of 10 cm and placed in a sterile polyethylene bag. Soil samples were air-dried for 48 h at room temperature and then mixed with calcium carbonate as a lignin peroxidase mediator and salt buffer.

2.2 Isolation and identification of Streptomyces

2.2.1 Isolation

Streptomyces isolates were recovered from saline soil samples using the dilution plate technique (Waksman, 1961). Ten grams of dry soil were suspended in 100 ml of sterile distilled water and shaken vigorously. The soil suspension was filtered through a sterile cotton cloth, and the filtrate was serially diluted to 10−4. Starch nitrate agar plates (pH 8.0) were inoculated with a ring of each diluted aliquot and then incubated at 35 °C for 7 days. Each separate colony was picked independently and cultured on a starch nitrate agar plate and incubated at 35 °C for 7 days. Pure cultures were kept at 4 °C for 1 month and then cultured periodically to avoid loss of the cultures.

2.2.2 Classical identification

Classical identification of Streptomyces was performed according to Cowan and Steel (1974). Streptomyces isolate was grown on inorganic salt starch agar (ISP4) for scanning electron micrograph. The culture was fixed in glutaraldehyde (2.5 % w/v), washed with water, and then fixed in osmium tetroxide (1 % w/v) for 1 h. The sample was washed twice with water and dehydrated in ascending ethanol before drying in a critical point dryer (Polaron E3000) and finally coated with gold and examined in a JEOLISM 541OLV scanning electron microscope at 15 kV.

2.2.2.1 Diaminopimelic acid detection

Ten mg of dried cells of a Streptomyces isolate were lysed for 18 h in 1 ml of 6 N HCl in a sealed Pyrex tube at 100 °C in a sand bath. After cooling, the tubes were opened and their contents were filtered through filter paper (Whatman No. 1). The sediment was washed with 3 drops of distilled water and the filtrate was dried 3 successive times in a water bath to remove hydrochloric acid, the remaining material was taken into 0.3 ml of distilled water and 20 μl of the liquid was loaded onto the filter paper (Whatman No. 1). A 10 μl spot of a 0.01 M mixture of meso-DAP and L-DAP was loaded onto chromatographic paper to run alongside the sample to serve as a reference standard. Stepdown chromatography was performed overnight using a solvent system (methanol–water-10 N HCl-pyridine) at a ratio of 80:175:2.5:10 (v/v). Amino acids were detected by air-dried spray chromatography with 0.2 % (w/v) ethanolic ninhydrin followed by heating for 2 min at 100 °C. DAP stains olive green to yellow, while other amino acids in the hydrolase give purple stains with this reagent and DAP agitation. L-DAP moves faster than meso-DAP (Becker et al., 1964).

2.2.3 Genetic identification

The 16S rRNA gene was sequenced using PCR and phylogeny was performed using BLAST analysis. Universal primers of 27f (5′-AGA GTT TGA TCC TGG CTC AG −3′) and 1525r (5′-AAG GAG GTG ATC CAG CC-3′) were used for 16S rRNA gene sequencing, where specific conditions exist; 35 cycles of 94 °C for 5 min and 60 s, followed by 55 °C for 60 s, 72 °C for 90 s and 72 °C for 5 min. For phylogeny, the Ribosomal Database Project's CHECK CHIMERA (https://rdp.cme.msu.edu/html/) programme was used to check for potential chimeric artefacts. Sequence data were analyzed using the ARB software package version.

2.3 Screening of Streptomyces isolates

Streptomyces isolates were screened for proteolytic activity, and protease production was detected by casein hydrolysis on skim milk agar (Mihara et al., 1991).

2.4 Blood sampling

Ten blood samples were drawn from cattle during slaughter, with each 10 cm sample drawn using a syringe, which was immediately sealed, placed in an ice bag, and transported to the laboratory.

2.5 Blood hemolysis

One hundred millimeters of nutrient agar (Difco, USA) was prepared in Erlenmeyer flasks and autoclaved. A sterile blood sample (10 ml) was added to each Erlenmeyer flask, gently shaken to avoid bubble formation, then poured into Petri dishes, and left overnight at room temperature. Uncontaminated plates were inoculated with the Streptomyces isolate, and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Hemolysis was observed as clear or green zones around the colonies (Collins and Lynee, 1995).

2.6 Hemolytic activity assay

The percentage hemolytic activity was evaluated according to Heidarian et al. (2019). The blood sample was centrifuged at 3500g for 15 min, the pellet containing RBCs was pooled and washed three times with phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). Bacterial suspensions were prepared at different concentrations (40, 20, 10, 5.0, 2.5 mg/ml). The bacterial suspension (500 µl) was added to RBCs, and the mixtures were incubated for 1 h at 37 °C and centrifuged at 1500g for 5 min. The optical density of the supernatants was measured at 545 nm using a UV–visible-spectrophotometer. Ferrous sulfate solution (65 mM) was used as a positive control, while phosphate buffer solution was used as a negative control (Chalasani et al., 2015).

2.7 Protease production

Extracellular protease produced by Streptomyces isolate was extracted using a sterile blood batch during submerged fermentation at 37 °C and 140 rpm for 48 h. Streptomyces isolate was grown on glucose peptone yeast-extract agar (glucose 5 g, peptone 5 g, yeast extract 3 g, distilled water 1000 ml, pH 8.0). The autoclaved medium was poured into Petri plates and left to solidify. Agar plates were blotted with 1 ml of homogenized suspension of Streptomyces isolate and incubated at 30 °C for 7 days. Five liters of blood were distributed into five flasks (2 L), each flask containing 1 L. All flasks were inoculated with 7-day-old Streptomyces culture (2 × 104 CFU/ml) and incubated with shaking at 37 °C and 140 rpm for 48 h. Streptomyces suspensions were pooled and filtered through a sterile cotton swab to harvest dense mycelia. The crude extract was centrifuged at 4 °C and 5000 rpm for 10 min to remove the cell-containing pellet and retain the protease-containing supernatant (cell free extract) (Chitte et al., 2011).

2.8 Protease purification

Different concentrations of saturated ammonium sulfate (10 % to 90 %) were added to the cell free extract containing protease. In each concentration fraction of saturated ammonium sulfate, the required parameters were evaluated including protease activity (U/ml), total activity (U/ml), total protein content (mg/ml), specific activity (U/mg), purification fold and yield (%) (Lowry et al., 1951; Abdulkhair, 2012). The protease-containing fraction was dialyzed overnight against phosphate buffer (pH 8.0) at 4 °C and then delivered to compact ion exchange column chromatography using diethyl aminoethyl cellulose (DEAE). Elution was performed using the same buffer and with a NaCl gradient (0.1 M to 0.6 M) (Andrews, 1964). The protease activity of the dilution fractions (each) was tested, and the active fractions were pooled, dialyzed against the same buffer overnight at 4 °C, and then delivered to a compact gel filtration column chromatography using Sephadex G-200 (Hames and Richwood, 1985). The active fractions were pooled and dialyzed under the same conditions to concentrate the protease. Electrophoresis of purified protease was determined using PAGE after staining with Coomassie brilliant blue (Laemmli, 1970).

3 Results

Thirty saline soil samples were collected from Dammam, Al-Khobar and Al-Ahsa in Saudi Arabia. The recovered Streptomyces isolates (410) were found to have various colored mycelial masses (Table 1). In Dammam, 170 isolates (41.4 %) were recovered, including 72 Gy isolates (42.4 %), 49 white (28.8 %), 24 green (14.1 %), 17 red (10 %) and 8 yellow (4.7 %). In Al-Khobar, 126 isolates (30.8 %) were recovered, including 43 Gy isolates (34.1 %), 47 white (37.3 %), 10 green (7.9 %), 8 red (6.3 %) and 18 yellow (14.3 %). In Al-Ahsa, 114 isolates (27.8 %) were recovered from, including 40 Gy isolates (35.1 %), 31 white (27.2 %), 20 green (17.5 %), 14 red (12.2 %) and 9 yellow (8.0 %). Halophilic Streptomyces bacteria showed a dense community in saline soil during winter due to high relative humidity and low temperature. It was found that gray isolates were more abundant (35.1 %) than white (27.2 %), green (17.5 %), red (12.2 %) and yellow (8.0 %) isolates.

District

Total no. of isolates

Color series of aerial mycelia

Gray

White

Green

Red

Yellow

Dammam

170 (41.4 %)

72 (42.4 %)

49 (28.8 %)

24 (14.1 %)

17 (10 %)

8.0 (4.7 %)

Al-Khobar

126 (30.8 %)

43 (34.1 %)

47 (37.3 %)

10 (7.9 %)

8.0 (6.3 %)

18 (14.3 %)

Al-Ahsa

114 (27.8 %)

40 (35.1 %)

31 (27.2 %)

20 (17.5 %)

14 (12.2 %)

9.0 (8 %)

Total Number

410 (100 %)

155 (37.8 %)

127 (31 %)

54 (13.2 %)

39 (9.5 %)

35 (8.5 %)

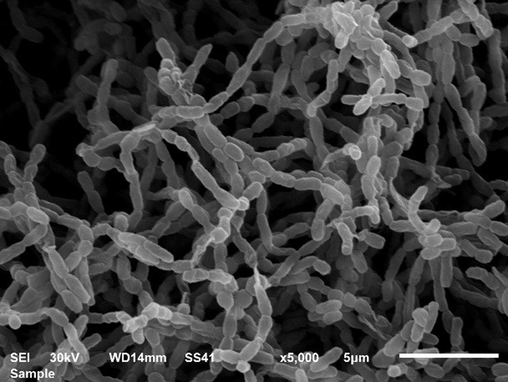

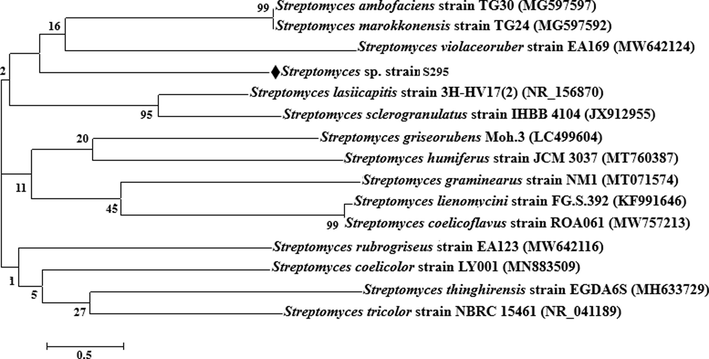

Streptomyces isolates (410) were screened for their proteolytic activity using skim milk agar, where 305 isolates showed proteolytic activity (Table 2). The lowest proteolytic activity (4.6 mm) appeared in isolates (S61 to S83) and (S126 to S189), while the highest proteolytic activity (33.8 mm) appeared in isolate S295. It was found that the proteolytic activity of isolates (S2 to S7), (S212 to S266) and (S296 to S305) was 12.4 mm, 12.6 mm and 12.8 mm, respectively. It was found that the proteolytic activity of isolates S84, S8, (S190 to S211), (S267 to S294), (S33 to S60), (S85 to S117), S1, (S118 to S125) and (S9 to S32) was 29.8 mm, 21.8 mm, 20 mm, 16.6 mm, 15.4 mm, 11.2 mm, 9.6 mm, 8.0 mm and 7.2 mm, respectively. The most effective isolate, S295, showed a gray mycelial mass (Fig. 1) on the surface of starch nitrate agar and was identified using the classical method by which cultural, morphological and physiological characteristics were determined (Table 3). In tryptone yeast extract broth (ISP1), good gray growth with colorless substrate mycelia and non-diffusible pigment appeared. On yeast-malt extract agar (ISP2), good gray growth with brown substrate mycelia and a creamy diffusible pigment appeared. Isolate S295 showed good gray growth with brown substrate mycelia and a light-brown diffusible pigment on oatmeal extract agar (ISP3) and inorganic salt starch agar (ISP4). On glycerol asparagine agar (ISP5), isolate showed poor white growth with brown substrate mycelia and non-diffusible pigment. On peptone yeast extract iron agar (ISP6) and tyrosine agar (ISP7), isolate showed good gray growth with brown substrate mycelia and a brown diffusible pigment. Isolate S295 showed spiral spore chains containing elliptical spores with a smooth surface (Fig. 2). It was observed that the isolate was non-motile and produced amylase, protease, catalase and nitrate reductase, while it was unable to produce lipase. It was found that isolate S295 was unable to produce melanoid pigment and hydrogen sulfide, and was unable to degrade xanthine and esculin. It was observed that the isolate contained LL-DAP in its cell wall and grew well on agar medium containing up to 15 % NaCl. Growth of the isolate was inhibited by streptomycin and amoxicillin (250 µg/ml) due to the absence of chromosomal and extrachromosomal resistance genes. D-glucose, D-fructose, D-galactose and sucrose as carbon sources and L-valine, L-alanine, L-lysine and L-proline as nitrogen sources were assimilated by isolate S295, while mannitol and L-histidine were not assimilated. Based on classical methods, isolate S295 was identified as S. violaceoruber, and based on the genetic method represented by 16S rRNA gene sequencing, isolate S295 was observed to be 99 % similar to S. violaceoruber EA169 (MW642124) as described in GenBank (Fig. 3).

Isolate

Proteolytic activity (mm) on skim milk agar

Plate 1

Plate 2

Plate 3

Plate 4

Plate 5

Mean

S1

10

8

12

10

8

9.6

S2 − S7

15

10

10

12

15

12.4

S8

22

22

20

25

20

21.8

S9 − S32

5.0

8.0

8.0

10

5.0

7.2

S33 − S60

17

15

17

13

15

15.4

S61 − S83

3.0

5.0

5.0

3.0

7.0

4.6

S84

30

25

32

32

30

29.8

S85 − S117

11.0

15.0

12.0

11.0

7.0

11.2

S118 − S125

7.0

10

11

5.0

7.0

8.0

S126 − S189

3.0

5.0

5.0

7.0

3.0

4.6

S190 − S211

20

18

22

20

20

20

S212 − S266

10

15

15

15

8.0

12.6

S267 − S294

15

18

18

20

12

16.6

S295

35

32

32

35

35

33.8

S296 − 305

10

12

12

15

15

12.8

Vertical view of a Streptomyces isolate S295 on starch nitrate agar.

Item

Test

Result

Growth rate

Color of mycelia

Color of the diffusible pigment

Aerial

Substrate

Cultural characteristics

Growth on ISP-1

Good

Gray

None

Not produced

Growth on ISP-2

Good

Gray

Brown

Cream

Growth on ISP-3

Good

Gray

Brown

Light brown

Growth on ISP-4

Good

Gray

Brown

Light brown

Growth on ISP-5

Poor

White

Brown

Not produced

Growth on ISP-6

Good

Grey

Brown

Brown

Growth on ISP-7

Good

Grey

Brown

Brown

Morphological characteristics

Gram staining

Positive

Spore chain color

Light gray

Spore chain shape

Spiral

Spore shape

Ellipsoidal

Spore surface

Smooth

Motility

Not motile

Physiological characteristics

Amylase, protease, catalase, nitrate reductase

Positive

Lipase, melanoid pigment, hydrogen sulfide

Negative

Xanthine and esculin degradation

Negative

Diaminopimelic acid (DAP)

LL-DAP

NaCl tolerance (up to 15 %)

Positive

Streptomycin and amoxicillin resistance

Negative

D-glucose, D-fructose, D-galactose, Sucrose

Positive

Mannitol

Negative

L-valine, L-alanine, L-lysine, L-proline

Positive

L-histidine

Negative

Scanning electron micrograph showing the morphological characteristics of Streptomyces isolate S295.

Phylogenetic tree of Streptomyces isolate S295.

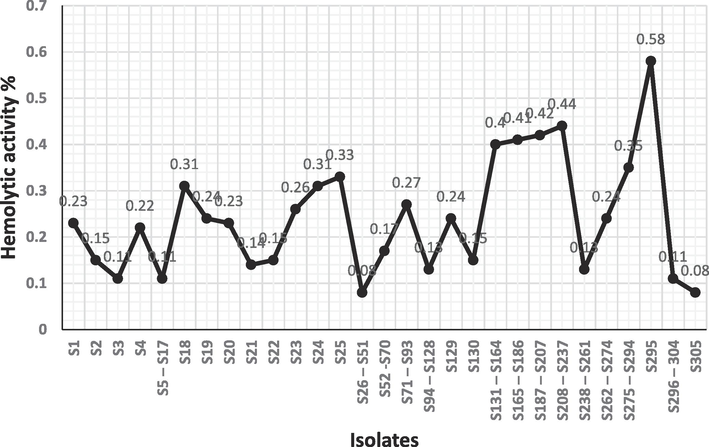

Of all the protease-producing isolates, 241 showed α-hemolysis and 64 showed β-hemolysis, including isolate S295. Protease-producing isolates showed varying ratios of hemolytic activity (Fig. 4). Isolates S1 and S2 showed 0.23 % hemolytic activity, while isolates S19, S129 and (S262 to S274) showed 0.24 % hemolytic activity. Isolates S4, S23, and (S71 to S93) showed hemolytic activity of 0.22 %, 26 %, and 0.27 %, respectively. Isolates S2, S22 and S130 showed hemolytic activity of 0.15 %, while isolates (S94 to S128) and (S238 to S261) showed hemolytic activity of 0.13 %. Isolates S21 and (S52 to S70) showed hemolytic activity of 0.14 % and 0.17 %, respectively. Isolates S3, (S5 to S17) and (S296 to S304) showed hemolytic activity of 0.11 %, while isolates S18 and S24 showed hemolytic activity of 0.31 %. Isolates S25 and (S275 to S294) showed hemolytic activity of 0.33 % and 0.35 %, respectively. The lowest percentage of hemolytic activity (0.08 %) was produced by isolates (S26 to S51) and S305. The highest percentage of hemolytic activity (0.58 %) was produced by isolate S295 followed by isolates (S208 to S237) (0.44 %), (S187 to S207) (0.42 %), (S165 to S186) (0.41 %) and (S131 to S164) (0.40 %).

Hemolytic activity percent of Streptomyces isolates.

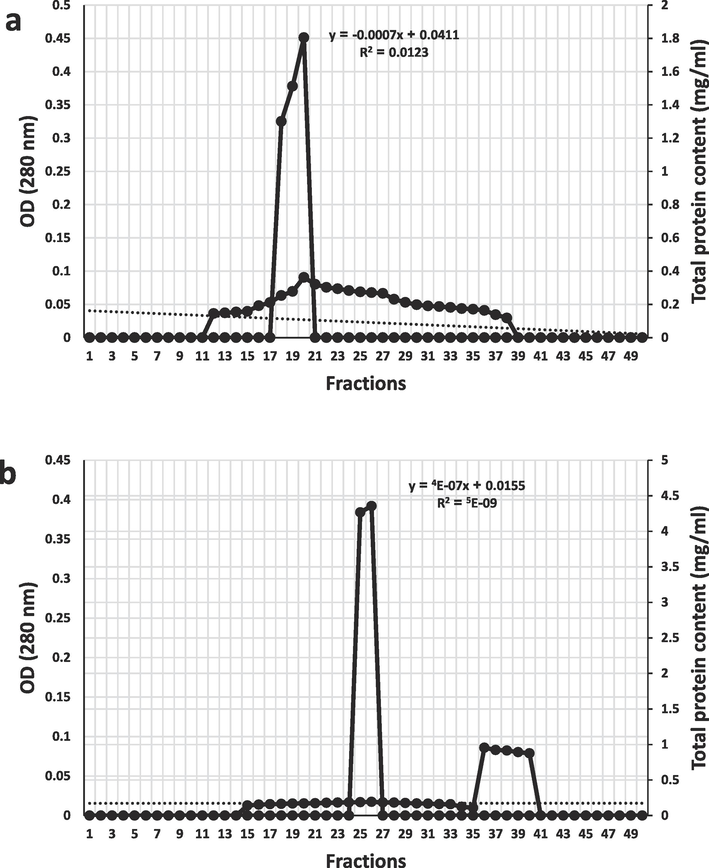

The protease was precipitated with 60 % saturated ammonium sulfate (Table 4), with an activity of 5.2 U/ml, total activity of 24,960 U/ml, specific activity of 463 U/mg, purification fold of 15.2, and yield of 78 %. The specific activity of the homogenate was low (30.4 U/mg) due to the presence of impurities, while the specific activity of the precipitated protease was high (463 U/mg) indicating high purity associated with a 15.2-fold and 78 % yield. The fraction containing the precipitated protease was dialyzed overnight at 4 °C against phosphate buffer (pH 8.0), purified using ion-exchange column chromatography (Fig. 5a) and eluted by phosphate buffer (pH 8.0). It was found that the active fractions were numbered from 18 to 20, pooled, dialyzed and purified using gel filtration column chromatography filled with sephadex G-200 (Fig. 5b) and eluted by phosphate buffer (pH 8.0). It was found that the active fractions were numbered 25 and 26, and they were pooled and dialyzed to concentrate. The purified protease was electrophoresed as a single band at 45 kDa.

Aliquots

Activity (U/ml)

Total activity (U/ml)

Total protein (mg/ml)

Specific activity (U/mg)

Purification fold

Yield %

Lysate

6.4

32,000

1050

30.4

1.0

100

10 %

0.0

0.0

40.2

0.0

0.0

0.0

20 %

0.0

0.0

40.9

0.0

0.0

0.0

30 %

0.0

0.0

50.7

0.0

0.0

0.0

40 %

0.0

0.0

51.3

0.0

0.0

0.0

50 %

0.0

0.0

52.4

0.0

0.0

0.0

60 %

5.2

24,960

53.9

463

15.2

78

70 %

0.0

0.0

52.1

0.0

0.0

0.0

80 %

0.0

0.0

50.8

0.0

0.0

0.0

90 %

0.0

0.0

48.6

0.0

0.0

0.0

Purification of alkaline protease (a) by ion-exchange column chromatography, (b) by gel filtration column chromatography.

4 Discussion

Halophilic Streptomyces isolates recovered from saline soils in Saudi Arabia showed variable distribution and diverse cultural characteristics based on collection site and mycelial mass color, respectively. Verma et al. (2022) reported that robust microbes that survive in extreme environments, including saline soil are a key aspect of new biotechnology, due to their ability to produce active metabolites with unique features. Actinobacteria reproduce intensively in soil during winter due to high relative humidity and low temperature. Meklat et al. (2020) demonstrated that a large and diverse community of actinobacteria, especially Streptomyces habits of saline soil. Halophilic Streptomyces displays unique physiological characteristics due to the harsh environmental conditions. Halophilic Streptomyces produces robust metabolites, such as hydrolytic enzymes and antimicrobial agents (Tong et al., 2016). Yamei et al. (2022) stated that, halophilic S. paradoxus D2-8 exhibits several activities, including promoting plant growth and providing halotolerance activity and alkalinity tolerance to sensitive plants to be able to grow under high salinity and alkalinity.

Several halophilic Streptomyces isolates (305) showed proteolytic activity, and the most powerful isolate S295 was identified as S. violaceoruber. A novel Streptomyces strain exhibits a peak proteolytic activity on skim milk agar at 40 °C and pH 8.0 (Boughachiche et al., 2016). Sufficient production of alkali metalloprotease by S. griseoflavus PTCC1130 is induced on medium containing zinc ion which stimulates proteolytic activity (Singhal et al., 2012). Proteolytic activity and productivity are directly proportional to the concentration of casein as the nitrogen source. It was observed that isolate S295 produced protease at 24 h and peaked at 96 h, while the highest biomass was observed at 120 h. These findings are similar to those of Nadeem et al. (2008), where S. pulvereceus MTCC 8374 produces the highest activity and productivity of alkaline protease at 40 °C and pH 9.0 and begins to gradually decrease beyond these limits until it disappears. He et al. (2023) reported that alkaline protease acts as an anticoagulant and is widely used in medical applications, as it effectively dissolves fibrin fibers that form blood clots. Therefore, alkaline protease is the first-line treatment of thrombosis and cardiovascular diseases. Streptomyces strain 214L-11 that is similar to S. fumanus NBRC 13042 T (98.88 %) produces a protease that extensively dissolves blood clots and is an important thrombolytic therapy.

The protease-producing isolates (241) showed α-hemolysis, while 64 showed β-hemolysis, including the most robust isolate S295. SudeshWarma et al. (2017) reported that primary fibrinolysis is the breakdown of blood clots, but with an overdose or prolonged period it may extend to the breakdown of RBCs and cause a serious problem. S. gulbargensis produces alkaline thermoprotease that is used to improve surgical instruments by degrading bound blood droplets. Different Streptomyces species are abundant producers of fibrinolytic enzymes, including proteases, which dissolve blood clots in a timely manner (SudeshWarma et al., 2017). Streptomyces showing alpha or beta hemolysis indicate proteolytic activity expressed by protease or other fibrinolytic enzymes. Actinobacteria, especially Streptomyces and halophiles in particular, produce bioactive compounds, including fibrinolytic enzymes such as protease with unique features, given the harsh conditions they endure and survive. These bioactive compounds are usually used in clinical and pharmaceutical fields (Suga et al., 2018; Amin et al., 2020).

Submerged fermentation was used to produce alkaline protease by Streptomyces isolate S295 on a small-scale. Alkaline protease was precipitated with 60 % saturated ammonium sulfate with 463 U/mg specific activity, 15.2 purification fold, and 78 % yield, indicating high purity, because harmful impurities were removed. The purified alkaline protease was found to have a high molecular weight, as it was electrophoresed as a single band at 45 kDa. Naira et al. (2014) reported that submerged fermentation relies on cheap natural materials as the primary batch, and is suitable for the production of alkaline protease by S. ambofaciens NRRL 2420 in immobilized form, which shows peak productivity (344 U/ml) with starch as carbon source and yeast extract as nitrogen source and at 30 °C, pH 8.5 and for 72 h. A global drug discovery and development program relies on the use of natural materials during submerged fermentation to produce bioactive compounds, especially those produced by actinomycetes due to their low cost, high efficacy, productivity and ecofriendly stance (Cortés-Albayay et al., 2019). The small alkaline protease (20.1 kDa) is produced by Streptomyces sp. LCJ12A and is precipitated with 70 % saturated ammonium sulfate (Parthasarathy and Gnanadoss, 2020). The partially purified protease shows activity as high as 100 % at 35 °C and pH 10 with casein, gradually decreasing to 90 % above the pH limit, 78 % at 45 °C and 60 % at 50 °C. Alkaline proteases have a wide range of molecular weight (15–45 kDa), such as those produced by S. albidoflavus (Bressollier et al., 1999) and Streptomyces sp. M30 (Xin et al., 2015) that have a molecular mass of 18 kDa and 37.1 kDa, respectively. Although submerged fermentation is widely used in the production of bioactive compounds, solid-state fermentation is also used, such as obtaining peak protease production by solid-state fermentation of wheat bran at 45 °C and pH 9.0 with casein as the substrate (Vishalakshi et al., 2009). Wild microorganisms, actinobacteria and Streptomyces in particular, are present in saline soils in Dammam, Khobar and Al-Ahsa in Saudi Arabia, but most of them are unexploited. Halophilic Streptomyces produces an active alkaline protease that dissolves blood clots (Park et al., 2007).

5 Conclusion

Various microorganisms, including actinobacteria can recover from extreme habitats, including saline soil. Halophilic actinobacteria, especially Streptomyces produce many active metabolites with unique features, including fibrinolytic enzymes which are used in industrial and medical fields. Alkaline protease is one of the fibrinolytic enzymes and is the first choice in treating cardiovascular diseases and dissolving blood clots. S. violaceoruber is a powerful producer of alkaline protease through which blood clots are dissolved in a timely manner. In Saudi Arabia, during the Hajj, a large amount of livestock is slaughtered because it is a religious ritual, which leads to the leakage of a huge amount of blood, which may clot if left without immediate treatment. Protease is considered the best way to treat blood clots resulting from the slaughter of livestock. Alkaline protease can be produced on an industrial scale using Streptomyces bacteria, which provide abundant quantities without the environmental pollution of those produced by chemical industries.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Fahad A. Al-Dhabaan: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Acknowledgments

The author sincerely thanks Head and members of Shaqra University and Head and members of Science and Humanities College for their great support to this work.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- The inhibitory effect of Streptomyces chromofuscus on β-lactamase of Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC-10145. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res.. 2012;6:1844-1854.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Microbiological and molecular insights on rare actinobacteria harboring bioactive prospective. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent.. 2020;44:1-12.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Estimation of the molecular weights of proteins by sephadex gel-filtration. Biochem. J.. 1964;91:222-233.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A comparative study on fibrinolytic enzymes extracted from six Bacillus spp. isolated from fruit-vegetable waste biomass. Food Biosci.. 2022;50:102149

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Measuring utility by a single-response sequential method. J. Soc. General Sys. Res.. 1964;9:226-232.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Optimization of alkaline protease production by Streptomyces sp. strain isolated from saltpan environment. Afr. J. Biotechnol.. 2016;15:1401-1412.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Purification and characterization of a keratinolytic serine proteinase from Streptomyces albidoflavus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.. 1999;65:2570-2576.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- An antimicrobial metabolite from Bacillus sp.: significant activity against pathogenic bacteria including multidrug-resistant clinical strains. Front. Microbiol. 2015;6:1335.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Production, purification, and biochemical characterization of a fibrinolytic enzyme from thermophilic Streptomyces sp. MCMB-379. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol.. 2011;165:1406-1413.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Microbiological Methods (seventh ed.). Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann Ltd.; 1995.

- The polyextreme ecosystem, salar de huasco at the Chilean Altiplano of the Atacama Desert houses diverse Streptomyces spp. with promising pharmaceutical potentials. Divers. 2019;11:69.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Manual for Identification of Medical Bacteria (third ed.). Cambridge shire: Cambridge University Press; 1974.

- Role of fibrinolytic enzymes in anti-thrombosis therapy. Front. Mol. Biosci.. 2021;8:680397

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bovine leukemia virus discovered in human blood. BMC Inf. Dis.. 2019;19:3891-3899.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A survey of zoonotic diseases contracted by South African veterinarians. J. s. Afr. Vet. Assoc.. 2023;74:72-76.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Gel Electrophoresis of Proteins. A Practical Approach (third ed.). London: Oxford University Press; 1985.

- Screening of a novel fibrinolytic enzyme-producing Streptomyces from a hyper-arid area and optimization of its fibrinolytic enzyme production. Ferment.. 2023;9:410.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Anti-microfouling activity of Glycomyces sediminimaris UTMC 2460 on dominant fouling bacteria of Iran marine habitats. Front. Microbiol. 2019;9:3148.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The role of fibrin (ogen) in wound healing and infection control. Semin. Thromb. Hemost.. 2022;48:174-187.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the band of bacteriophage T4. Nat.. 1970;227:680-685.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Protein measurements with the folin phenol reagent. Biol. Chem.. 1951;193:265-275.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Isolation, classification and antagonistic properties of alkali tolerant actinobacteria from Algerian Saharan soils. Geomicrobiol. J. Taylor. Franc.. 2020;37:826-836. Doi: 1080/01490451.2020.1786865

- [Google Scholar]

- A novel fibrinolytic enzyme extracted from the earthworm, Lumbricus rubellus. Jpn. J. Physiol.. 1991;41:461-472.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effect of medium composition on commercially important alkaline protease production by Bacillus licheniformis N-2. Food Technol. Biotechnol.. 2008;46:388-394.

- [Google Scholar]

- Optimization of alkaline protease production by Streptomyces ambofaciens in free and immobilized form. Am. J. Biochem. Biotechnol.. 2014;10:1-13.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Nakae, R., Murai, Y., Yokobori, S., 2022. Biomarkers in neurological injury: Fibrinogen, fibrinogen/fibrin degradation products (FDPs), and d-dimer. In: Biomarkers in Trauma, Injury and Critical Care. Rajendram, R., Preedy, V.R., Patel, V.B. (eds). Biom. Dis. Meth. Disc. Appl. Springer, Cham. Pp. 1-15. Doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-87302-8_3-1.

- Park, S., Mei-Hong, L.I., Kim, J., Sapkota, K., KIM, J.E., Choi, B.S., Yoon, Y.H., Lee, J.C., Lee, H.H., Kim, C.S., Kim, S.J., 2007. Purification and characterization of a fibrinolytic protease from a culture supernatant of Flammulina velutipes Mycelia. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 71, 2214–2222. Doi: 10.1271/bbb.70193.

- Purification and characterization of extracellular alkaline protease from Streptomyces sp. LCJ12A isolated from Pichavaram mangroves. J. Appl. Biol. Biotechnol.. 2020;8:15-20.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Rui, wu., Guiguang, C., Shihan, P., Jingjiang, Z., Zhiqun, L., 2019. Cost-effective fibrinolytic enzyme production by Bacillus subtilis WR350 using medium supplemented with corn steep powder and sucrose. Sci. Rep. 9, 6824. Doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-43371-8.

- Blood clot contraction: Mechanisms, pathophysiology, and disease. Res. Pract. Thromb. Haemost.. 2023;7:100023

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Studies on production, characterization and applications of microbial alkaline proteases. Int. J. Adv. Biotechnol. Res.. 2012;3:653-669.

- [Google Scholar]

- Production of fibrinolytic protease from Streptomyces lusitanus isolated from marine sediments. Mat. Sci. Eng. 2017;263:022048

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hamuramicins A and B, 22-membered macrolides, produced by an endophytic actinomycete Allostreptomyces sp. K12–0794. J. Antibiot.. 2018;71:619-625.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Streptomyces daqingensis sp. nov., isolated from saline–alkaline soil. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol.. 2016;66:1358-1363.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Verma, J., Sourirajan, A., Dev, K., 2022. Bacterial diversity in 110 thermal hot springs of Indian Himalayan region (IHR). 3 Biotech. 12, 238.

- Production of alkaline protease from Streptomyces gulbargensis and its application in removal of blood stains. Ind. J. Biotechnol.. 2009;8:280-285.

- [Google Scholar]

- Waksman, S.A., 1961. The Actinomycetes. Vol. II. Classification, Identification and Description of Genera and Species, second ed. Baillière, Tindall and Cox, Ltd., London.

- Purification and characterization of a novel extracellular thermostable alkaline protease from Streptomyces sp. M30. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol.. 2015;25:1944-1953.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A salt-tolerant Streptomyces paradoxus D2–8 from rhizosphere soil of Phragmites communis augments soybean tolerance to soda saline-alkali stress. Pol. J. Microbiol.. 2022;71:43-53.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Modifiable risk factors, cardiovascular disease, and mortality in 155 722 individuals from 21 high-income, middle-income, and low-income countries (PURE): a prospective cohort study. Lancet.. 2020;7:795-808.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]