Translate this page into:

Development of eco-environmental nano-emulsified active coated packaging material

⁎Corresponding author. msa.nrc@gmail.com (Saber Ibrahim)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Packaging film modified with PLA was prepared and fully characterized. Modified packaging will be extend the shelf life time for food packaging. Treatment of chicken fillet with lactic acid was compared with packaging film. Sensory score of chicken fillet packaged in PLA were significantly higher.

Abstract

Coated packaging film with nano-emulsified polylactic acid (PLA) was prepared as an extended shelf life package for chicken fillet. PLA was prepared by direct polycondensation to be prepared after that nanoparticles by solvent displacement as potential coating for packaging systems. The characterizations of PLA were done by thermo-gravimetric measurement size exclusion chromatography and differential scanning calorimetry. Additionally, the particle size distribution was measured by dynamic light scattering which exhibited narrow particle size distribution with mean particle size ≈70 nm. The effect of PLA nanoparticles coating was evaluated as an active packaging for a chicken fillet stored at 4 °C. An aerobic plate, coliforms counts (APC) and sensory score were also studied. The Low molecular weight PLA (LM-PLA) reduces APC by 1.5 log cfu/g and coliforms count by 75 MPN/g than the control and extended the storage time more than 2 days. Meanwhile, a high molecular weight PLA (HM-PLA) significantly reduces APC by 2.1 log cfu/g and coliforms count by 107 MPN/g lower than the control beside extended the storage time by more than 3 days. Although dipping in lactic acid 1% for 5 min and 2% for 10 min was increased the storage time to 11th and 15th days respectively. Moreover, the sensory score of chicken fillet packaged in PLA were significantly high.

Keywords

Antimicrobial packaging

Biodegradable polymers

Polylactic acid (PLA)

Bioactive packaging films

Chicken fillet shelf life

1 Introduction

Recently, polylactic acid gained a great attention for the preparation of an active coating film for meat, chicken and most of the food protein base (Harshe et al., 2017; Ibrahim et al., 2019). The PLA is an aliphatic linear polymer derived from lactic acid. PLA was certified to be used as biodegradable packaging materials or coating film from the Drug Administration and Food, USA (Xiong and He, 2010).

Azeotropic condensation is one of the most common synthesis methods to prepare PLA as well as ring opening of cyclo-monomer lactide, can be applied to synthesis PLA (Garlotta, 2001) Linearly. The azeotropic condensation, without any chain extender, is performed as good chance to prepare PLA with low polydispersity. The properties of polymer film would enhancement in different medical or packaging applications (Orozco et al., 2017). Various techniques to prepare nano-PLA are reported such as displacement of the solvent, emulsification/evaporation, salting out and emulsion/solvent diffusion (Galindo-Rodriguez et al., 2014; Pinto Reis et al., 2016). The solvent displacement is the most applied technique due to its easily processing and high yield of production (Plapied et al., 2011). The surrounding environment, nature of packaging material and biological activity are the most factors affecting on the shelf life of food products (Robertson, 2010). Food contamination with bacteria can be made changes in odor, sensory and appearance of packaged food (Raouche et al., 2011).

Instant addition of antimicrobials in the polymeric formulation was caused inhibition of non-desired germs. On the other hand, the presence of microbials survivor will be continued growing, which causes several complicated interactions with food or sequence degradation resultant in decrease the shelf life (Kim et al., 2012). In addition, gradual decrease in antimicrobials’ counts may be caused development of the antimicrobial-resistant mutants (Chi-Zhang et al., 2014). There is also an increase in the consumer demand for national, natural and organic goods. This is created new challenges in providing efficient food preservation, specifically in the area of microbial safety (Suppakul et al., 2013).

Active packaging overcomes these former disadvantages that use packaging as a delivery system to release the antimicrobial into packaged food efficiently, resulting extension the product’s features, shelf life and protection. Active packaging system based on enhanced inner environment of the package using novel packaging inhibitors for bacterial activity extends the food shelf life and observed qualities (Quintavalla and Vicini, 2012). Organic acids, plant extracts and bacteriocins are traditional food additives (Hamdy et al., 2015).

Lactic acid is an attractive opportunity for manufacture of poultry products. US department of agriculture, states that lactic acid is a safe substance (GRAS). Antimicrobial polymers prospected to be used in modification of active packaging. The lethality of organic acids against Salmonella enterica and the effect on pathogen from chicken surfaces were stated with lactic acid and others organic acids (Hamdy et al., 2015). The effect of lactic acid on physiological and morphological properties of Salmonella Enteritidis, Escherichia coli and Listeria monocytogenes was studied (Chenjie et al., 2015). In addition, lactic acid/acetic acid blend and peracetic acid to reduce salmonella on packaged chicken parts (Alejandra et al., 2018).

PLA is one of the bio-source polymers beside its eco-environmentally and biodegradation safely (Torres et al., 2014; Becerril et al., 2017). PLA will have more prospective studies in the future with a great attention on improving food quality and safety. Moreover, linear polyethyleneimine was used as antimicrobial polymer to extend the shelf life of chilled fillet (Saber et al., 2016). Thus, microbiological, biochemical and investigation tests could be determining where the antimicrobial goes, in what quantities and the method of antimicrobials growth in testing media that simulate food systems (Becerril et al., 2017).

PLA is one of unique biocompatible, and bioresorbable polymers, which makes it suitable for use in biomedical engineering to form implants in field of reconstruct tissue, and to control the dosage of biologically active substances (Urbaniak-Domagala et al., 2016). In addition, pure PLA fiber did not show any antibacterial activity (Liu et al., 2017). Polylactic acid nanoparticles antimicrobial activity improved by the presence of lemongrass oil which assisted the formation of well-separated NCs and provided enhanced antimicrobial properties, since lemongrass is known for its antimicrobial character (Liakos et al., 2016).

A new trend was recently established by designing active packaging materials without any further additives to food. Although some studies deal with the modification of antimicrobial packaging. A few commercial active packaging products are found in the market, which could be referred to the hygiene considerations as well as the cost considerations (Sung et al., 2013).

Therefore, a developed polyethylene sheet with antimicrobial PLA coating for its suitability as a bio-based active packaging material, antimicrobial film, are employed in this work. The PLA effect or lactic acid release from PLA coating layer were evaluated on inhibition of the bacterial counts in refrigerated chicken fillet to extend its shelf life. Automatic coater technique was applied to combining the desirable properties of polyethylene film and antimicrobial PLA film within less cost than pure antimicrobial PLA film alone, and more antimicrobial efficiency than polyethylene film only.

2 Experimental

2.1 Materials

Lactic acid (LA), 90% was purchased from PURAC bioquimica (Barcelona, Spain) and was purified through further reduce the water content using a molecular distillation method before used. Stannous octoate and p-toluenesulfonic as catalysts were delivered from Sigma (Germany). Chloroform and methanol are used without any further purification. Polyethylene sheets were received as a gift from techno-plastic Co. 6 October city, Egypt.

2.2 Synthesis of polymers

In 50 mL Schlenk tube, (1.03 g) l-lactic acid and two different ratios of catalyst (Stannous octoate) 0.3 wt% and 0.6 wt% were charged. The mixture was stirred for 30 min at room temperature followed by addition of acetone (20 mL). The reaction mixture was immersed in oil bath at 150 °C for 12 h under reduced pressure 10−3 mbar. The Schlenk reaction tube was raised up from oil bath and cooled gradually. The precipitate was filtrated and kept in vacuum oven at 50 °C overnight. Two different molecular weights are prepared (LM-PLA and HM-PLA) according to the catalyst ratios.

2.3 Measurements and analysis

TA Instruments Q100 was used to investigate the thermal behavior of prepared polymers. Recovery from thermal history was carried out through heating cycle up to 200 °C. After that, measurement cycle was applied with heating rate 5 °C/min.

Size exclusion chromatography (SEC) was used to determine the molecular weights by Water’ instrument with differential refractometer as a detector and quaternary pump controller model 600. Waters HT6E and HR4E columns were applied for the assignment of the molecular weights of prepared PLA samples. Polystyrene in THF at 30 °C was used to calculate the molecular weights as standard.

Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) Model Quanta 250 FEG, was used to investigate the morphological structure and particle shape of PLA. In addition, the particle size was carried out with Zetasizer Nano S (Malvern Instr., UK) concepted on dynamic light scattering at incident angle 173°.

2.3.1 Preparation of active packaging materials

Nanoparticles of PLA were prepared by dissolve 25 mg of prepared PLA polymers and then dissolved in 5 mL of acetone. The polymer solution was added to 10 mL of Millipore water in drop wise rate. The mixture was stirred overnight to remove the acetone. Resultant solution containing PLA nanoparticles were coated polyethylene sheets (10 × 10 cm) with automatic coater and dried in vacuum oven at 30 °C over night to be used as active packaging materials.

2.3.2 Preparation of chicken fillet samples

Chicken fillet without skin was obtained from local manufacture as one lot and transported under refrigeration to the laboratory within two hours. Upon arrival, the chicken fillet was divided into 5 groups each consists of 3 parts. The first was the control group which packaged conventionally in polyethylene films. The second and third groups were packaged in (HM-PLA and LM-PLA) films, respectively. The fourth and fifth groups were dipped in lactic acid solutions, 1% for 5 min (LA 1%) and 2% for 10 min (LA 2%), respectively. Then, the fourth and fifth groups were hanged on to be airier drained and stored in polyethylene bags. After that, all samples were stored at 4 °C and examined for sensory and bacteriological characteristics at zero, 2nd, 4th, 6th, 8th, 9th, 11th and 15th day. Samples examination ended by reaching aerobic plate count higher than log 5 cfu/g and/or coliforms count 100 MPN/g according to Egyptian Standards for chilled poultry and rabbits, No. 1651 (Egyptian Standards: ES No. 1651, 2005).

2.3.3 Sensory examination

According to Oral et al. (2009) and Parlapani et al. (2014) a five trained test panel (from the analysts of Food Hygiene Department in Animal Health Research Institute) evaluation of the samples was performed for the color, odor and texture characteristics, then the average was recorded as overall sensory score ranging from 5 = very good, 4 = good, 3 = accepted, 2 = dislike to 1 = very dislike. Each assessor evaluates three trials.

2.3.4 Microbiological examination

According to Downes et al. (2001), samples were homogenized with peptone water (Oxoid) (1:10). Serial dilutions were prepared for further bacterial counts. Aerobic plate count was done using pour plate technique onto plate count agar (Oxoid) and incubating, 35 °C for two days. Coliforms count using most probable number technique on lauryl tryptose broth (Oxoid), 35 °C for two days and confirmed on brilliant green bile (2%) broth (Oxoid) at 35 °C for two days.

2.3.5 Statistical analysis

The experiment was conducted in three repetitions with complete randomized design. Data were analyzed by using the mixed procedure from SPSS software (release 20, IBM CO) after a logarithmic transformation. Means were separated by Fisher’s test with least significant difference at α = 0.05.

3 Results and discussion

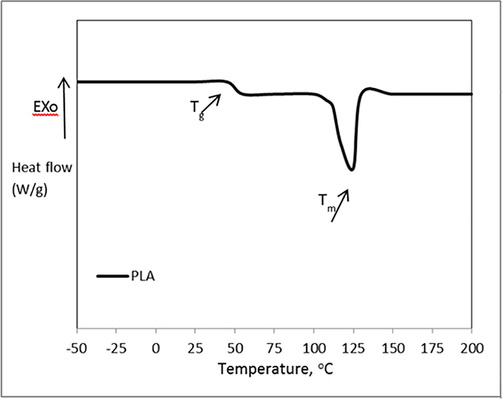

3.1 Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC)

DSC was used for understanding the thermal behavior concepts and determine thermal indices, glass transition temperature (Tg) and melting Temperature (Tm). the measured values were reflected the state of polymer chain within different temperature ranges from room temperature up to high (heating) or low (cooling) temperature.

DSC thermograms are presented in Fig. 1. The measured glass transition temperatures of PLA have high agreement with standard values of PLA homopolymer at this composition (Harshe et al., 2017; Garlotta, 2001), Tg ≈ 48 °C where the melting point Tm ≈ 137. Previous thermal parameters verified the suitability of PLA to be applied as polymer coating for packaging materials sheets. Low melting temperature gives an opportunity to be applied as melted coat through manufacture line or as soluble coat through film coater or even more as spray techniques. These unique multi-coating techniques are open the window of industrial applications in many fields to use PLA coat as antimicrobial film on many substrates according to desirable coating process.

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) thermograms of LM-PLA.

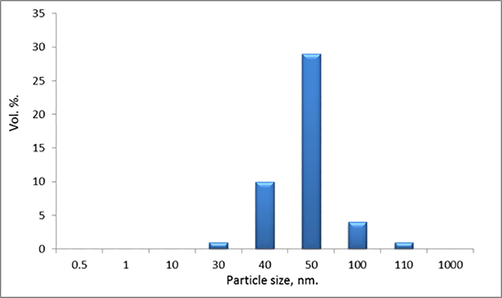

3.2 Particle size

The dynamic light scattering DLS is a unique characterization tool for determining the particle size and hydrodynamic radii in the case of solution state with Brownian motions.

As shown in Fig. 2, particle size distribution of LM-PLA that dispersed in aqueous medium presents relative particle diameter measurement distribution over narrow range from 30 to 110 nm with percentage more than 90% of particles overall volume distribution.

Shows particle size distribution of PLA homopolymers as dispersed in aqueous medium.

Low polydispersity, i.e. narrow distribution of particle size, of PLA was indicated to homogenized distribution of coated film over polyethylene sheet. These are confirmed continuous coating layer with ±70 nm difference in thickness as the mean of particle size. Particle size behavior gives PLA film a range of application from nano-scale to microscale as coating for packaging films.

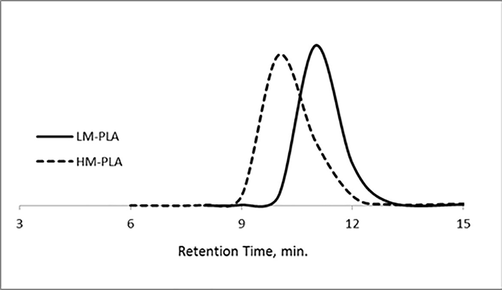

3.3 Size exclusion chromatography

Molar weights have a critical role in the stability of a colloidal, chain length, topography, duration of degradation, thermal stability and capability to cross-linking. The PLA molar ratios (number average molecular weight, Mn and weight average molecular weight, Mw) were measured by size exclusion chromatography (SEC).

Mn, MW, and polydispersity index (PDI) of PLA were tabulated in Table 1. Molar ratios of prepared PLA as a homopolymer coating were investigated. Relatively low polydispersities were detected with a unimodal chromatograph as shown in Fig. 3. The broadness of HM-PLA is higher than of LM-PLA this due to nature of condensation polymerization reaction with increasing the molecular weight. According to polymer behaviors in polycondensation polymerization technique, the resulted polymers have controlled polydispersity as well-defined polymer chain.

Mn, g/mol

Mw, g/mol

PDI (Mw/Mn)

PLA

11.6 × 103

1.5 × 104

1.3

SEC chromatographs of LM-PLA and HM-PLA homopolymers.

Molecular weight plays a vital role in coating behavior and its characteristics. Two targeted molecular weights are exhibited flexible polymer film which considered as the main desirable properties in coating for flexible plastic film. In addition, polydispersity indicates to similarity in chains length which presents equivalent antimicrobial behavior over the coating film.

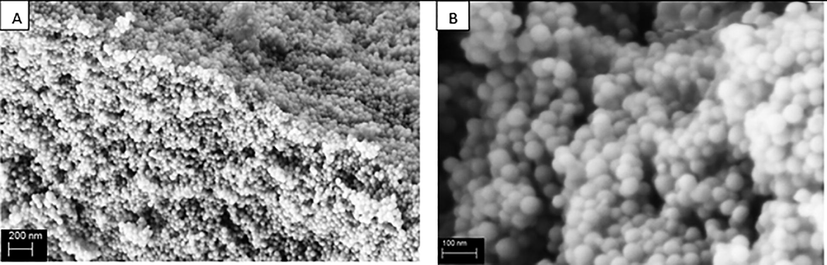

3.4 Scanning electron microscope (SEM)

Fig. 4 illustrates SEM micrographs of LM-PLA copolymer. Spherical polymer particles were detected with narrow particle size distribution with range from 40 to 80 nm. Small nanoparticles of PLA enable continuous prepared film with high volume/area ratio. PLA nano-coating film was produced in excellent behavior with a huge affected surface area.

SEM micrographs of PLA homopolymers with magnifications a) 25 K and b) 100 K with average particle diameter 40-80 nm.

DLS and SEM results are in agreement with terms of particle size plus little deviation due to relative measurement states from liquidity in DLS to solidity state in SEM imaging. Polymer particles can swell or shrink corresponding to nature of homopolymer in solution during DLS measurement. In case of SEM, particle could be extrovert to give large size or highly dried under vacuum conditions to give small size.

3.5 Sensory and microbiological examination

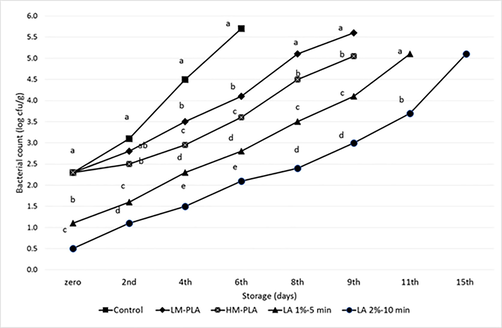

The initial aerobic plate count (APC) level (see Fig. 5) in the chicken fillet was 2.3 log cfu/g, which is lower than that was reported by de Melo et al. (2012). This count significantly (P < 0.05) decreased after dipping in lactic acid 1% for 5 min (LA1%).

The effect of various treatment on the bacterial account with storage intervals, having different letters in the same day are significantly differ (p<0.05).

Furthermore, dipping of chicken fillet in lactic acid 2% for 10 min (LA2%) significantly (P < 0.05) lowered the APC rather than those in both of control and LA1%. On the other hand, this dipping significantly altered the color of chicken fillet, which in turn affected on all sensory score as shown in Table 2 with decrease from 5 in control to 4 in both of dipping treatments. This effect of direct treatment with lactic acid is reported. Bilgili et al. (1997) reported that organic acids treatment may cause bleaching and darkening of carcass. The effect of lactic acid on color mainly depends on its concentration and application method (Grajales-Lagunes et al., 2012). Lactic acid treatment increased the paleness and decreased the redness of beef cuts (Jimenez Villarreal et al., 2003). Means having different letters in the same raw is significantly differ (p < 0.05).

Days

Treatment

Control

LM-PLA

HM-PLA

LA 1%-5 min

LA 2%-10 min

Zero

5a

5 a

5a

4b

4b

2nd

4a

5b

5b

4a

3.5a

4th

4a

5b

5b

3.5a

3c

6th

3a

5b

5b

3.5a

3c

8th

–

4a

4.5ab

3.5c

3c

9th

–

3a

4b

3a

3a

11th

–

–

–

3a

2.5a

15th

–

–

–

–

2.5

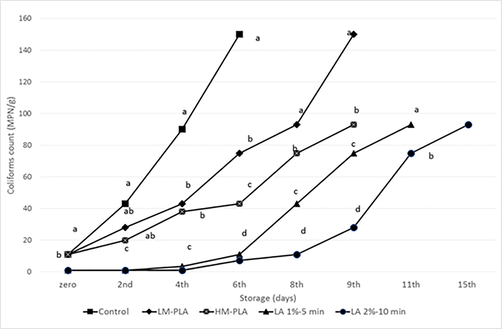

For coliforms counts (see Fig. 6) the counts decreased (P < 0.05) from 11 MPN/g in control to <3 MPN/g in both lactic acid dips. During refrigerated storage, the control samples exceeded the maximum limit of bacterial counts (5 log cfu/g for APC and 100 for coliforms count) before the six day. Nevertheless, the overall sensory score still accepted, the samples considered unfit after 5 storing days, which was significantly (P < 0.05) as the lowest storage period regarding to other treatments.

Coliforms count of Chicken Fillet Stored at 4 °C in Different Treatments and Packaging, means having different letters in the same day are significantly differ (p<0.05).

Inhibition of the microorganism growth rate can be carried out by antimicrobial agents through isolated the contact between microorganism and active agent (Quintavalla and Vicini, 2002). Therefore, the applied treatment with antimicrobial agent would extend the storage period in treated sample than control. Lactic acid is passively diffused through cell wall of bacteria and internalizing into pH 7 dissociating into negative radical and hydrogen cations. Release of the hydrogen cations changed the pH medium to acidic medium which strongly inhibit the bacteria growth (Ricke, 2013).

From the 4th day of storing, the effect of packaging in LM-PLA films begins to be notable. Bacterial counts were reduced (P < 0.05) than control by one log cycle for APC and from 90 to 43 MPN/g for coliforms. The results increased the fitness of the samples till the 8th day of storage. Meanwhile, packaging in HM-PLA films begin to be notable from the 2nd day of storage, reaching 2 log reduction cycles in APC and from 150 to 43 MPN/g in coliforms compared to the control in the 6th day of storing. The former results increased to the fitness of the samples until the 9th day of storage. Packaging in HM-PLA films reduced (P < 0.05) both of bacterial counts lower than in LM-PLA films so that increased the fitness of samples by one day. Overall sensory scores were similar (P > 0.05) in both PLA films till the 8th storage day, although they were the highest (P < 0.05) scores concerning control and dipping treatments.

The concentration of an antimicrobial agent embedded in packaging materials is directly proportional to the inhibition efficacy of a microorganism growth (Zinoviadou et al., 2009). Thus, the account of microorganism can be reflected the activity of antimicrobial agent (Ceylan and Fung, 2014). On the other hand, Ponce et al., concluded that there is a limit of active components with certain concentration of inhibition, and when the count is higher than this limit, the growth rate is unrecognized.

Dipping chicken fillet in lactic acid has a great reduction (P < 0.05) for APC and coliforms counts and extends the storing days more than those of control and PLA films moreover, the increase of fitness of the samples until the 11th day using LA 1%-5 min and 15th day using LA 2%-10 min. On the other hand, overall sensory score was reduced (P < 0.05) by dipping treatments more than control and PLA films packaging due to color changes. This reduction continues through the storing period. Although, dipping in lactic acid decreased the bacterial counts and increased the storage life of samples more than PLA films, the lowered overall sensory characteristics (mainly due to changes in color and texture) give advantage to packaging in PLA films, Thus, the PLA reserved the sensory characteristics of chicken fillet more than control and dipping treatments. On the contrary, the direct addition of PLA to the food which may alter the sensory attribute, incorporation of organic acid in packaging material shows a steady slow and consistent release over the time beside maintain a high concentration in the product (Ponce et al., 2018).

Bautista et al. (1997), reported that 1.24% lactic acid treatment reduced APC by 2.4 log cycles and coliforms by at least 1.5 log compared with initial inoculation levels on turkey carcasses. Whereas, Okolocha et al., observed a 0.6-log CFU/ml reduction in APC and a 1.1-log CFU/ml reduction in Enterobacteriaceae when poultry carcasses were dipped in 1% lactic acid (Okolocha and Ellerbroek, 2005).

The 2% lactic acid rinse was the most effective treatment in the field study, producing a significant 2-log reduction (P < 0.01) in APC and coliform levels in comparison with the untreated carcasses (Killinger et al., 2010).

4 Conclusion

Lactic acid can be incorporated into the bio-based polymer through formation of PLA nanoparticles and retain their inhibitory effect against microbial growth in the chicken fillet. LM-PLA significantly reduced APC by 1.5 log cfu/g and coliforms count by 75 MPN/g more than control and extends the storing time more than 2 days. Meanwhile, HM-PLA significantly reduced APC by 2.1 log cfu/g and coliforms count by 107 MPN/g more than control and extends also the storing time more than 3 days. Although dipping in lactic acid 1% for 5 min and 2% for 10 min increased the storing time to 11th and 15th days respectively, sensory score of chicken fillet packaged in PLA were significantly higher.

Acknowledgements

Authors have deep greeting to Zepter Company, Egypt, which give us packaging bags and weeding bag instrument as a gift. Authors have great thankful for nanomaterial investigation laboratory, Central lab. Network, National Research Centre for technical support and materials investigation.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Efficacy of lactic acid, lactic acid–acetic acid blends, and peracetic acid to reduce salmonella on chicken parts under simulated commercial processing conditions. J. Food Protect.. 2018;81:17.

- [Google Scholar]

- The determination of efficacy of antimicrobial rinses on turkey carcasses using response surface designs. Food Microbiol.. 1997;34:279.

- [Google Scholar]

- Combination of analytical and microbiological techniques to study the antimicrobial activity of a new active food packaging containing cinnamon or oregano against E. coli and S. aureus. Anal. Bioanal. Chem.. 2017;388:1003.

- [Google Scholar]

- Broiler skin color as affected by organic acids: influence of concentration and method of application. Poult. Sci.. 1997;77:752-757.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antibacterial mechanism of lactic acid on physiological and morphological properties of Salmonella Enteritidis, Escherichia coli and Listeria monocytogenes. Food Control. 2015;47:231.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effective control of Listeria monocytogenes by combination of nisin formulated and slowly released into a broth system. Int. J. Food Microbiol.. 2014;90:15.

- [Google Scholar]

- Microbiological quality and other characteristics of refrigerated chicken meat in contact with cellulose acetate-based film incorporated with rosemary essential oil. Braz. J. Microbiol.. 2012;43:1419.

- [Google Scholar]

- Compendium of Methods for the Microbiological Examination of Foods. American Public Health Association; 2001.

- Egyptian Standards: ES No. 1651 for chilled poultry and rabbits, 2005. Egyptian Organization for Standardization and Quality, Arab Republic of Egypt.

- Physicochemical parameters associated with nanoparticle formation in the salting-out, emulsification-diffusion, and nanoprecipitation methods. Pharm. Res.. 2014;21:1428.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of lactic acid on the meat quality properties and the taste of pork serratus ventralis muscle. Agric. Food Sci.. 2012;21:171-181.

- [Google Scholar]

- Improving the antimicrobial efficacy of organic acids against Salmonella enterica attached to chicken skin using SDS with acceptable sensory quality. LWT – Food Sci. Technol.. 2015;64:558.

- [Google Scholar]

- Active paper packaging material based on antimicrobial conjugated nano-polymer/amino acid as edible coating. J. King Saud Univ. Sci.. 2019;31:1095-1102.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lipid, instrumental color and sensory characteristics of ground beef produced using trisodium phosphate, cetylpypiridium chloride, chloride dioxide or lactic acid as multiple antimicrobial interventions. Meat Sci.. 2003;65:885-891.

- [Google Scholar]

- Validation of a 2 percent lactic acid antimicrobial rinse for mobile poultry slaughter operations. J. Food Prot.. 2010;73:2079.

- [Google Scholar]

- Properties of nisin-incorporated polymer coatings as antimicrobial packaging materials. Packag. Technol. Sci.. 2012;15:247.

- [Google Scholar]

- Polylactic acid—lemongrass essential oil nanocapsules with antimicrobial properties. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2016;9(3):42.

- [Google Scholar]

- The influence of acid and alkaline treatments on pathogens and the shelf life of poultry meat. Food Control. 2005;16:217.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of absorbent pads containing oregano essential oil on the shelf life extension of overwrap packed chicken drumsticks stored at four degrees Celsius. Poult. Sci.. 2009;88:1459-1465.

- [Google Scholar]

- Microbiological spoilage and investigation of volatile profile during storage of sea bream fillets under various conditions. Int. J. Food Microbiol.. 2014;189:153-163.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nanoencapsulation I. Methods for preparation of drug-loaded polymeric nanoparticles. Nanomed. Nanotechnol.. 2016;2:8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fate of polymeric nanocarriers for oral drug delivery. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci.. 2011;16:228.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of edible coatings enriched with natural plant extracts: in vitro and in vivo studies. Postharvest Biol. Technol.. 2018;49:294.

- [Google Scholar]

- Combined effect of high pressure treatment and anti-microbial bio-sourced materials on microorganisms’ growth in model food during storage. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol.. 2011;12:426.

- [Google Scholar]

- Perspectives on the use of organic acids and short chain fatty acids as antimicrobials. Poult. Sci.. 2013;82:632.

- [Google Scholar]

- Food packaging and Shelf Life: A Practical Guide. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 2010.

- The effect of active packaging hydrogel based on polyethyleneimine/polyacrylamide on the safety and shelf life of chilled fillet. J. Chem. Pharm. Res.. 2016;8:1100.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial agents for food packaging applications.Trends. Food Sci. Technol.. 2013;33:110.

- [Google Scholar]

- Active packaging technologies with an emphasis on antimicrobial packaging and its applications. J. Food Sci.. 2013;68:408.

- [Google Scholar]

- Near critical and supercritical impregnation and kinetic release of thymol in LLDPE films used for food packaging. J. Supercrit. Fluids. 2014;85:41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Plasma modification of polylactide nonwovens for dressing and sanitary applications. Text. Res. J.. 2016;86:72.

- [Google Scholar]

- Development of poly(lactic acid)/chitosan fibers loaded with essential oil for antimicrobial applications. J. Nanomater.. 2017;7:194.

- [Google Scholar]

- The biological evaluation of the PEG/PLA amphiphilicdiblock copolymer. Polym. Plast. Technol. Eng.. 2010;49:1201.

- [Google Scholar]

- Physico-chemical properties of whey protein isolate films containing oregano oil and their antimicrobial action against spoilage flora of fresh beef. Meat Sci.. 2009;82:338.

- [Google Scholar]