Translate this page into:

Depositional environments of Danian/Selandian of Kurkur Formation, Kurkur Oasis, south Western Desert, Egypt

⁎Corresponding author. mymohamed@ksu.edu.sa (Mohamed Youssef)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

In order to document the depositional environments of the Kurkur Formation in Southwestern Desert, Egypt, four surface sections measured in this region from north to south as follows: Gebel Garra, Wadi Abu-Sayal, Kurkur Oasis, and Sinn El-Kaddab. Planktonic foraminifera indicate that the age of Kurkur Formation in the study area is Danian to Selandian. Microfacies analysis shows graduation from wackestones, floatstones, and packstones in the lower part to oolitic and bioclastic grainstones in the upper section. The lower part of Kurkur Formation characterized by calcareous foraminifera assemblages, whereas arenaceous types are concentrated toward the uppermost part. Bivalves, gastropods, and echinoids are the most abundant macrofossils. Using the microfacies analyses and fossil content, the Kurkur Formation in the studied area deposited in middle neritic zone for the lower part, which is synchronous with the beginning of the Cenozoic transgression in the study area, and changed upward to inner neritic and supratidal environments.

Keywords

Microfacies

Benthic foraminifera

Paleoenvironments

Kurkur

south Western Desert

Egypt

1 Introduction

The Paleogene succession in Egypt spans a vast expanse of land. These rocks span from the border between Sudan and Egypt in the Western Desert. The region of southern Egypt had multiple maritime transgressions throughout the Paleogene period. The region that experienced the most significant Transgression, which persisted until the Early Eocene (Luger 1988). These violations were intermittently interrupted by modest regressive episodes. The transgressions in southern Egypt were not widespread, but rather limited to the Dakhla basin, mostly because to tectonic factors. During the Maastrichtian-Paleocene period, the southern region of the Upper Nile Platform was characterized by marginal marine facies, as described by Luger in 1988.

The geological formations in southern Egypt during the upper Cretaceous-lower Eocene period show a gradual separation of the Nile Valley and the Garra El Arbain facies from the oases of Dakhla, Kharga, and Paris to the oases of Kurkur and Dungul. The Nile Valley facies is separated into four units: the Dakhla Formation, Tarawan Formation, Esna Formation, and Thebes Formation. The Garra El Arbain facies is found in the western and southern regions of Aswan, as well as in the southern region of Kharga Oasis along Darb El Arbain (Isaawi 1972). The examined area contains the Cretaceous-Paleogene succession, namely the Garra El Arbain facies. This succession is divided into four units: the Dakhala Formation, the Kurkur Formation, the Garra Formation, and the Dungul Formation (Issawi 1972). The Paleogene succession in the research area has been investigated by several authors, including Hendriks et al. (1984, 1987), Hewaidy (1994), Faris and Hewaidy (1995), and Hewaidy et al. (2014).

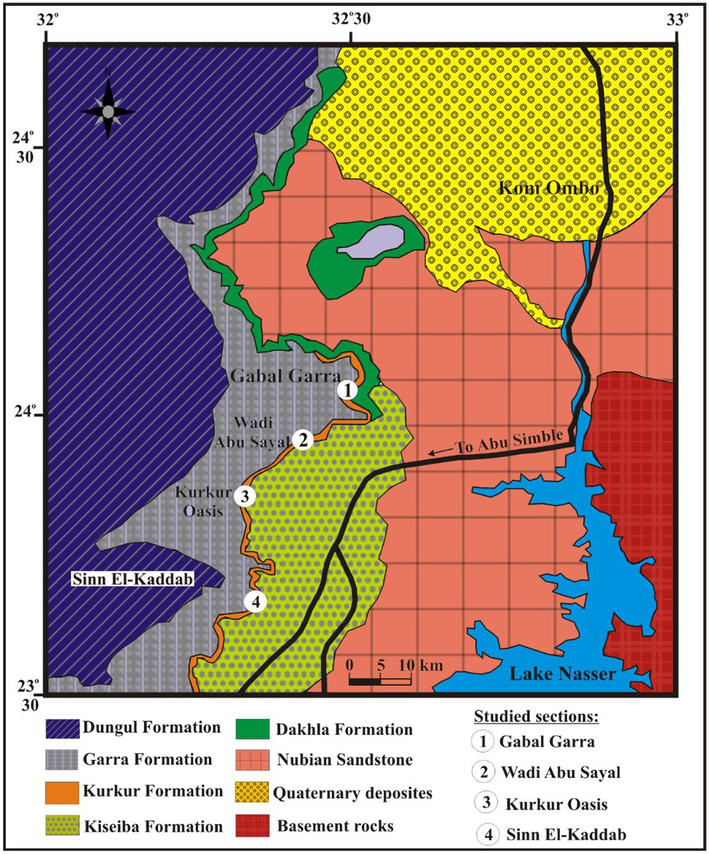

The Kurkur Formation has garnered significant attention from numerous authors. The paleoenvironments of the Kurkur Formation were examined by analyzing several fossil groups, as documented by Schrank (1983), Hewaidy and Soliman (1993), Strugo and Hewaidy (1993), Tantawy (1994), Ouda and Tantawy (1996), Hewaidy and Azab (2002), Youssef (2003), Aref and Youssef (2004), and Youssef and Mutterlose (2004). Previous research did not focus on using microfacies analysis to interpret the depositional conditions that existed during the sedimentary sequence deposition. Hence, the primary objective of this study is to utilize a combination of microfacies analysis and foraminiferal content to determine the depositional environments of the Kurkur Formations in the Southwestern Desert of Egypt (Fig. 1).

Geological map and locations of the studied sections.

2 Geological setting

The Arabian craton, which formed during the late Paleozoic era, experienced the intrusion of shallow seas that originated from parts of the Tethys system, likely located north of Egypt. There is a consensus on a distinct separation between the Arabian nucleus (Arabo Nubian massive) and the shelf areas, however the boundaries between the various units of the shelf area are poorly defined (Said, 1961). The shelf area of Egypt, which surrounds the Arabo-Nubian massif, can be separated into two parts throughout the Late Cretaceous and Early Paleocene periods: the Stable Shelf and the Unstable Shelf (Said, 1962) as shown in Fig. 1. The Stable Shelf, located in southern Egypt, is characterized by indistinct boundaries and is covered by a layer of sediments measuring less than 1000 m in thickness. This encompasses the extensively spread Nubia sandstone, which is overlain, in places that are not basins, by shallow marine deposits from the significant Late Cretaceous-Early Tertiary transgression. The Stable Shelf encompasses the basement exposures of the Arabo Nubian craton in eastern Egypt. To the west, it forms a large tectonically low region (Kerdany and Cherif, 1990). This region can be divided into two primary intracratonic basins that generally extend in a north–south direction. The Dakhla Basin spans the western region of the country and has a significant opening towards the north in the Western Desert. The upper Nile Basin spans the eastern regions of the country, stretching from a longitude between Kharga and Dakhla to the west, perhaps reaching even further east beyond the current coastline of the Red Sea. The basin likely covered the area where the current basement exposures of the Red Sea range are located. These exposures were raised during the late Paleocene and subsequent periods (Bisewski, 1982). The basins are bounded on the southwest by the Calanscio-Uweinat-Gilf El Kebir High and on the south by a series of uplifts known as the Uweinat-Aswan High. These uplifts extend eastwards to the Eastern Desert basement exposures. The elevation of this landform, which is covered by a thin layer of sedimentary rock from the Mesozoic era, is believed to have been created from the late Paleozoic to early Mesozoic periods through the upward movement along significant faults that run from east to west.

The initial extensive marine advance of the Mesozoic period over the upper Nile basin took place during the Cenomanian epoch and extended to at least the latitude of Aswan. The Turonian regression had an impact on the upper Nile basin. The Coniacian period signifies a transgression event (Said, 1990) that resulted in the sea advancing inland, reaching as far as Nubia and beyond, and submerging the entire Nile basin. The Santonian period was characterized by a regression, during which the sea was limited to the tectonic basins of northern Egypt. A significant violation occurred in the Campanian period, during which a shallow sea engulfed the majority of Egypt. Following a brief period of regression in the early Maastrichtian, the sea progressed and engulfed more extensive regions of Egypt than at any other period. The depth of the sea increased significantly. In the northern regions, there was a buildup of pristine chalk deposits in the Sudr area (Sinai and Gulf of Suez) and the Khoman area (north Western Desert). The southern region experienced the deposition of shales, specifically in the lower part of the Dakhla formation. During the Paleocene, a significant portion of the Stable Shelf experienced flooding from the sea due to the greatest transgression. The identification of a maritime Paleocene outcrop in Gebel Abyad, located in northern Sudan (Barazi and Kuss, 1987), indicates that the shoreline during that time was approximately 400 km further south. The Gebel Abyad facies bears resemblance to the Arbain facies found in the Paleocene of southern Egypt, suggesting the possibility that both were deposited in a single basin. In the Early Eocene, the shoreline moved back to southern Egypt, resulting in the coverage of a large embayment with relatively thin and consistent sediments, measuring less than 500 m in thickness. Sediments thicker than 500 m are only found in a few number of basins.

3 Lithostratigraphy

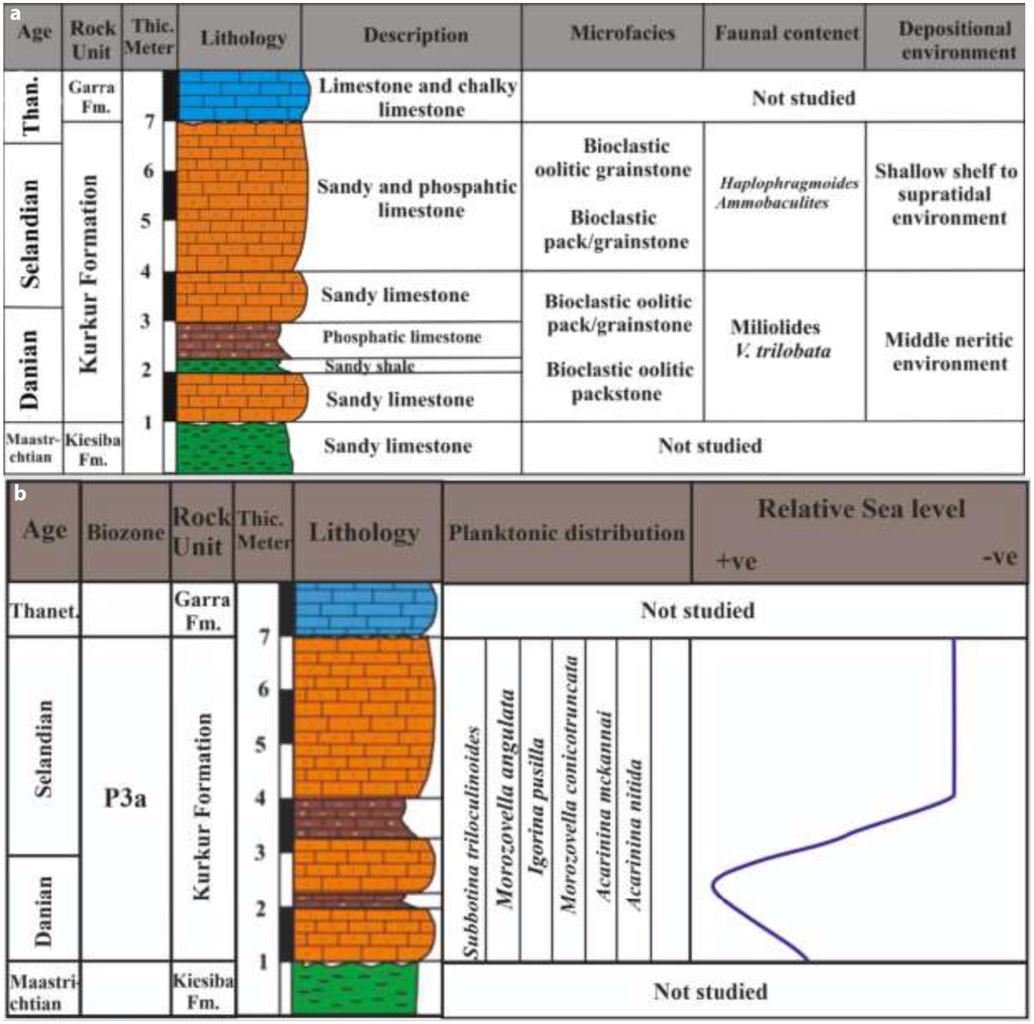

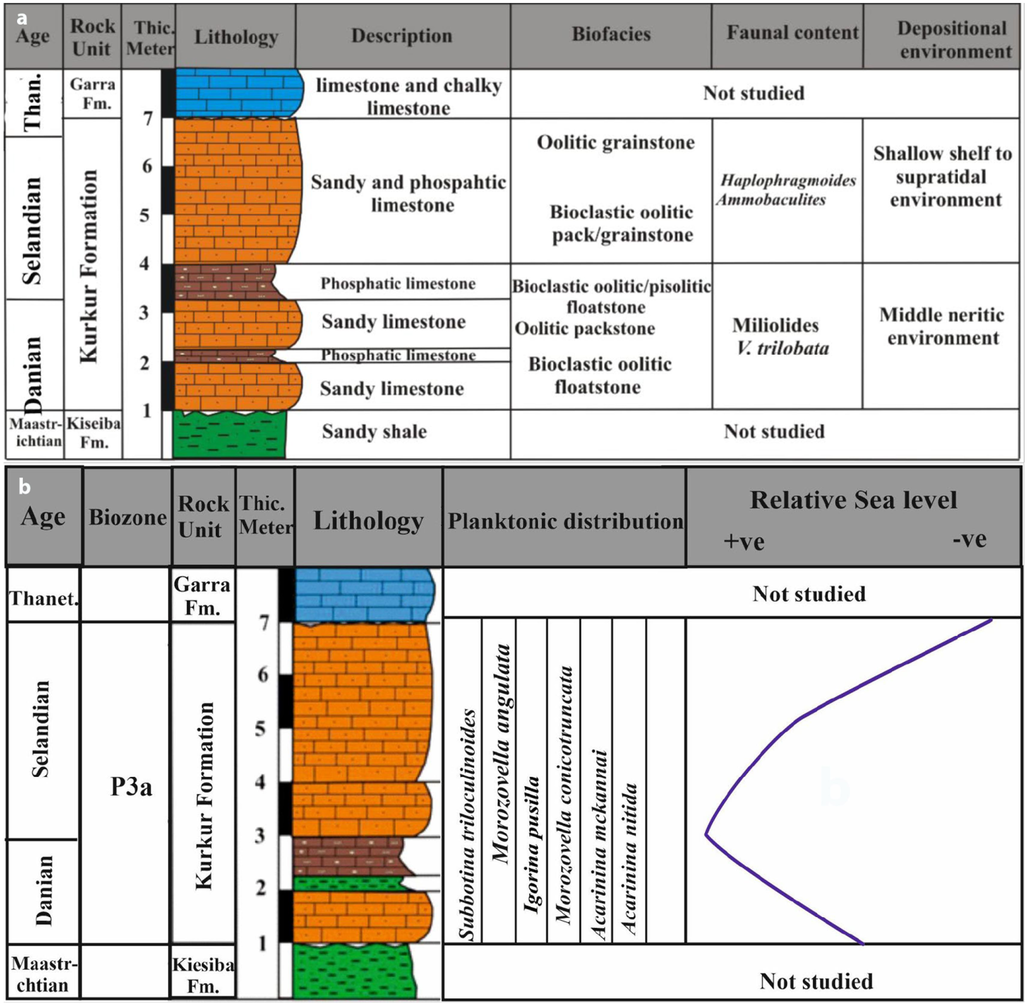

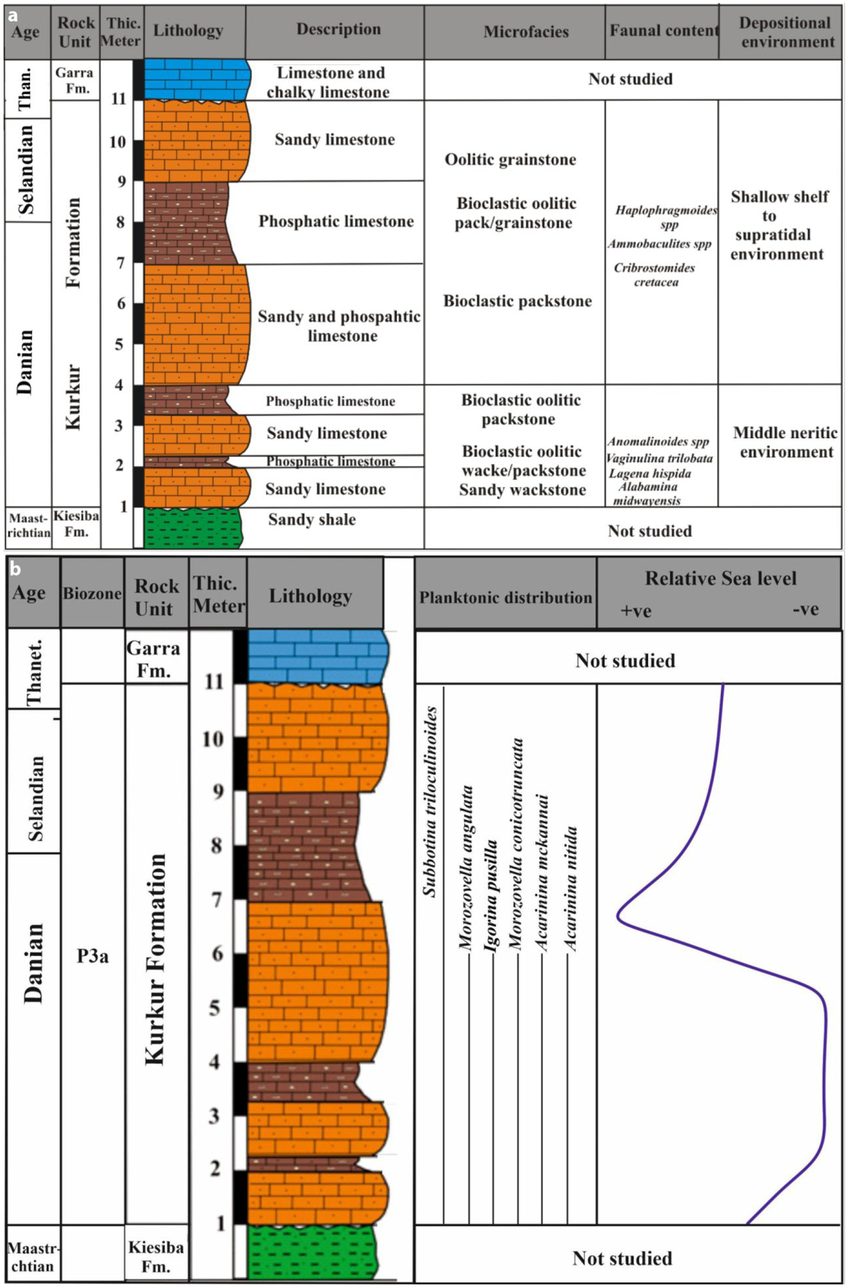

The term “Kurkur Formation” was introduced by Issawi in 1968 to characterize the brownish sediments that consist of at least two carbonate beds separated by shale or sandstone strata, together with sandy clay intercalations. The word “Kurkurstufe,” initially coined by (Blankenhorn 1900) to refer to the fossil-rich layers at Kurkur Oasis, has been supplanted. The Kurkur Formation in the study region is distinguished by its brownish color, which stands out in contrast to the greenish or grayish shale of the Kiseiba Formation below and the white, chalky limestone beds of the Garra Formation above (Table 1: supplementary). The Kurkur Formation consists of brown to dark brown, hard to semi-hard, argillaceous limestone with rich fossil content, phosphatic deposits, and oolitic limestone. It also contains layers of silty shale and marl. The Kurkur Formation is observed on the steep slope of Sinn El Kaddab and forms a noticeable shelf that sits above the Kiseiba Formation in the southern region of Gebel Garra. The Kurkur Formation is located in close proximity to the wadi bottom at Kurkur Oasis due to its specific structural features, as noted by Issawi 1968. The thickness of the rock layers in the Gebel Garra, Wadi Abu-Sayal, Kurkur Oasis, and Sinn El Kaddab portions are 6 m, 6 m, 10 m, and 20 m, respectively. The Kurkur Formation has substantial differences in both thickness and lithology while moving from the southern to the northern regions. The succession has a significant amount of fossils, specifically bivalves, gastropods, and echinoids. The shale intercalations include a large number of microfossils, but in other areas, there is a complete absence of fauna. The comprehensive lithostratigraphic sequence of the Kurkur Formation in the examined sections is outlined in Figs. 2–5 a.

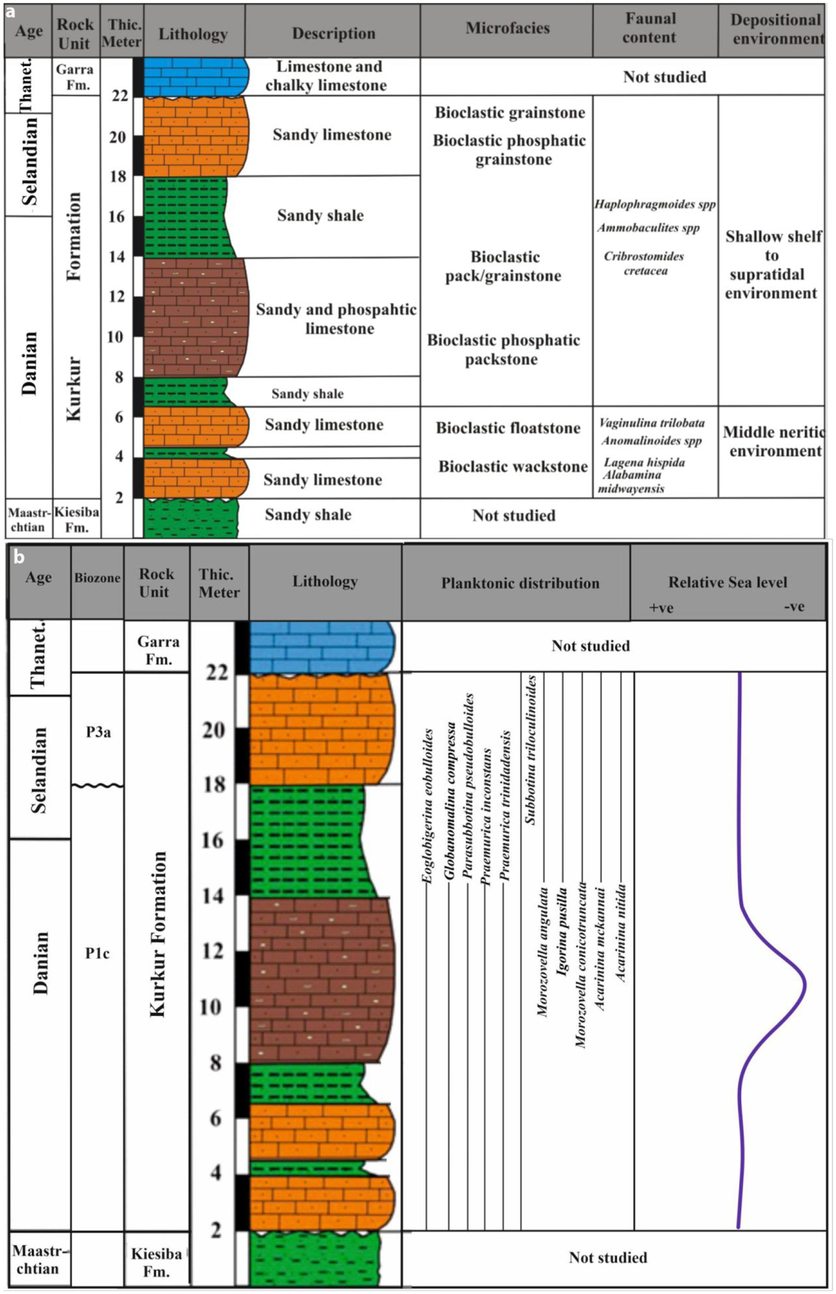

a) Composite lithostratigraphic section of the Kurkur Formation, foraminiferal content, microfacies and depositional environments at Gebel Garra section; b) range chart of planktonic foraminifera and the sea level change of the studied succession at Gebel Garra section.

a) Composite lithostratigraphic section of the Kurkur Formation, foraminiferal content, microfacies and depositional environments at Wadi Abu-Sayal section; b) range chart of planktonic foraminifera and the sea level change of the studied succession at Wadi Abu-Sayal section.

a) Composite lithostratigraphic section of the Kurkur Formation, foraminiferal content, microfacies and depositional environments at Kurkur Oasis section; b) range chart of planktonic foraminifera and the sea level change of the studied succession at Kurkur Oasis section.

a) Composite lithostratigraphic section of the Kurkur Formation, foraminiferal content, microfacies and depositional environments at Sin El-Kaddab section; b) range chart of planktonic foraminifera and the sea level change of the studied succession at Sin El-Kaddab section.

4 Materials and methods

Four stratigraphic outcrops were surveyed, and 25 rock samples including macrofossils were obtained to describe the microfacies analysis and depositional settings of the middle to early late Paleocene Kurkur carbonates in the Southwestern Desert of Egypt. The studied sections, listed in order from north to south, consist of Gebel Garra (32° 30′E, 24° 09′N), Wadi Abu-Sayal (32° 24′E, 23° 58′N), Kurkur Oasis (32° 8′E, 23° 45′N), and Sinn El-Kaddab (32° 19′E, 23° 40′N). A total of twenty-five thin sections were meticulously constructed for the purpose of conducting microfacies study. The microfacies description and interpretation followed the classification of Dunham (1962). The shale intercalations were collected for the purpose of extracting foraminifera. The samples were washed and prepared using the conventional approach (Rückheim et al. 2006) to separate the foraminifera. A twofold treatment was applied to ensure complete disaggregation.

5 Biostratigraphy

The biostratigraphic scheme for the planktonic foraminifera of the Paleocene-Early Eocene is established using the Tethyan zonal concepts proposed by Berggren et al., 1995. Based on the vertical distribution of planktonic foraminifera in the examined sequence, the Kurkur Formation can be divided into two distinct biozones: Praemurica trinidadensis (P1d) and Morozovella angulate (P3a). The age of the succession from the early to late Paleocene period has been determined by studying the planktonic foraminifera found in the Kurkur formation. The presence of planktonic foraminifera in the sediments of the Kurkur Formation was infrequent. Hewaidy and Soliman (1993) determined that the Kurkur Formation (M. uncinata Zone) is of middle Paleocene age. The Early-Late Paleocene is attributed to the Kurkur Formation, as stated by Luger 1985. The Kurkur Formation, specifically the Early-Late Paleocene period, has been identified based on the presence of planktonic foraminifera and calcareous nannofossils (Youssef and Muterlose 2004). The Kurkur Formation in the examined area contains a hiatus that includes Zone P2 (Praemurica uncinata Zone). For the range chart and water depth please (see Figs. 6-9b).

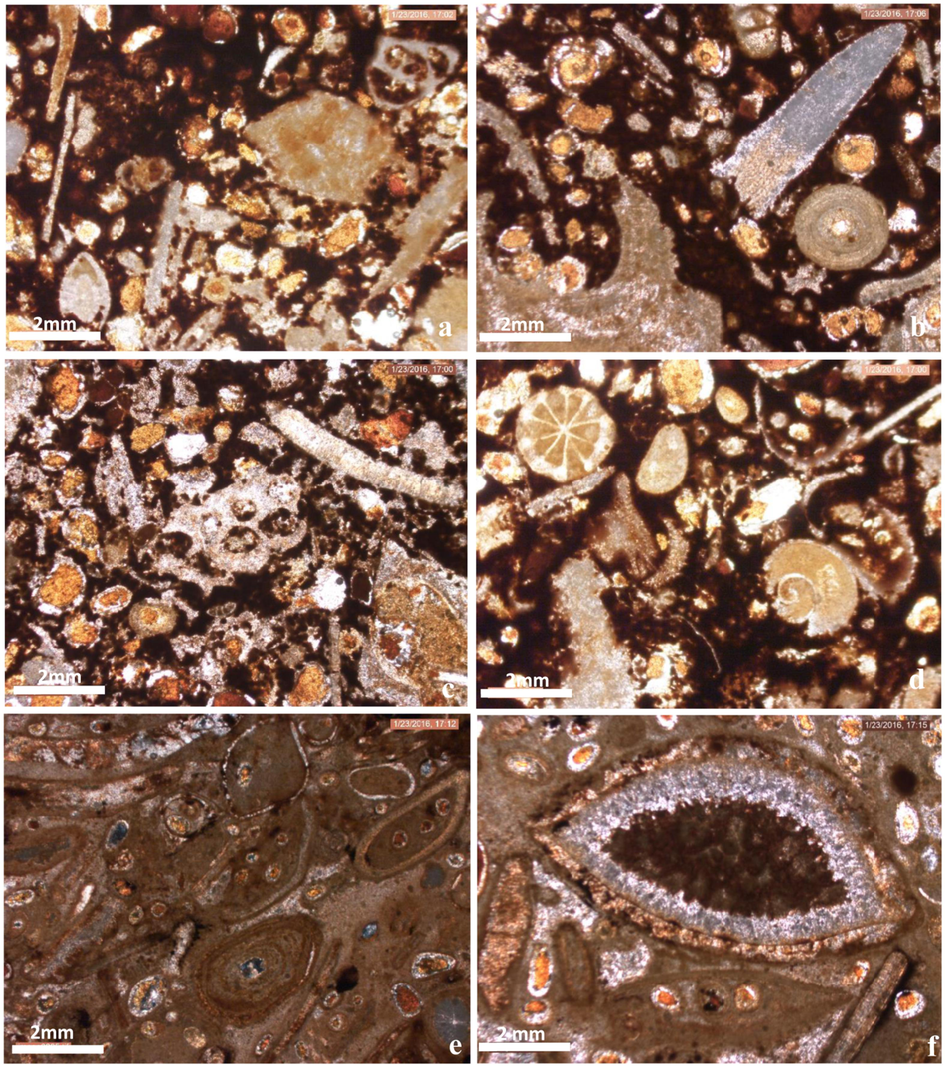

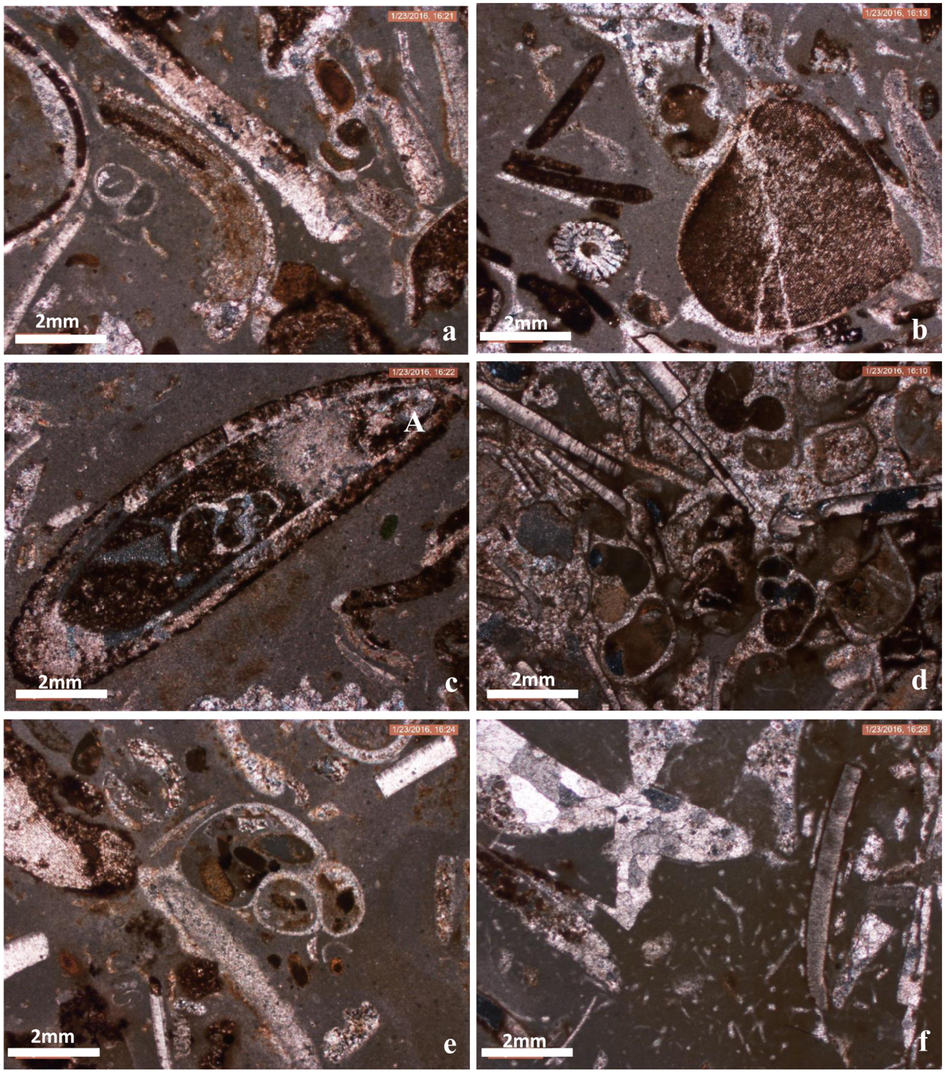

Examples of the microfacies analyses of the Gebel Garra section. A: Foraminifera bioclastic packstone/grainstone with benthic foraminifera and shell fragments, lower part of the section. B: Bioclastic oolitic packstone/grainstone with concentric oolites, echinoids, and shell fragments, lower part of the section. C: Bryozoan bioclastic packstone/grainstone with phosphatic pellets, bryozoans, and shell fragments, lower part of the section. D: Coralline oolitic bioclastic packstone/grainstone with corals, gastropods, and shell fragments, lower part of the section. E: Oolitic grainstone with concentric oolites, upper part of the section. F: Ostracodal oolitic bioclastic grainstone with recrystallized ostracods, concentric oolites, and shell fragments, upper part of the section.

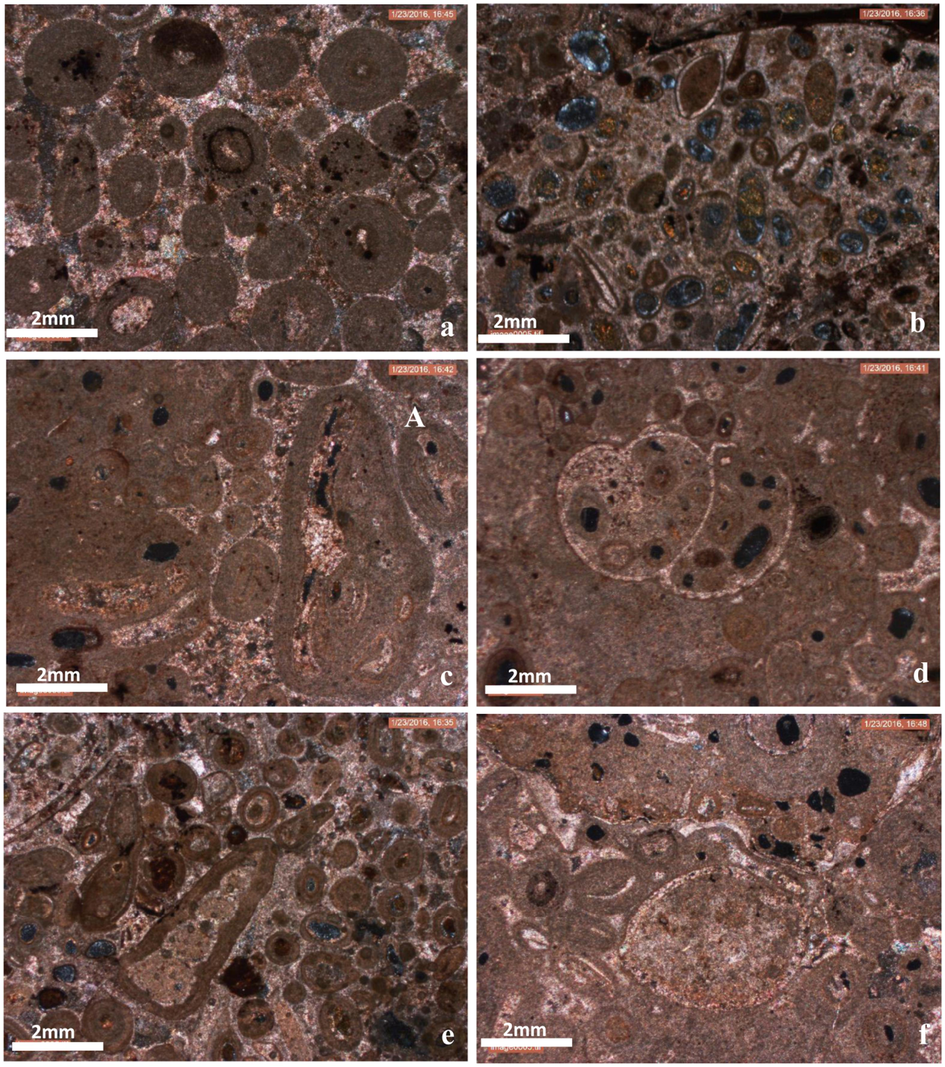

Examples of the microfacies analyses of Wadi Abu-Sayalsection. A: Oolitic grainstone with fine to medium concentric oolites, upper part of the section. B: Ostracodal oolitic packstone/grainstone with ostracods, benthic foraminifera, and oolites, lower part of the section. C: Pisolitic–oolitic packstone/floatstone, lower part of the section. D: Foraminifera wackestone/packstone with planktonic foraminifera and oolites, lower part of the section. E: Oolitic packstone/grainstone with gastropods and concentric oolites, upper part of the section. F: Ostracodal oolitic packstone/grainstone, lower part of the section.

Examples of the microfacies analyses of Kurkur Oasis section. A: Gastropod oolitic bioclastic packstone, upper part of the section. B: Gastropod oolitic bioclastic packstone, upper part of the section. C: Bioclastic packstone, upper part of the section. D: Echinoidal oolitic bioclastic packstone, upper part of the section. E: Oolitic packstone with concentric fine to medium oolites, lower part of the section. F: Bioclastic packstone with shell fragments, upper part of the section.

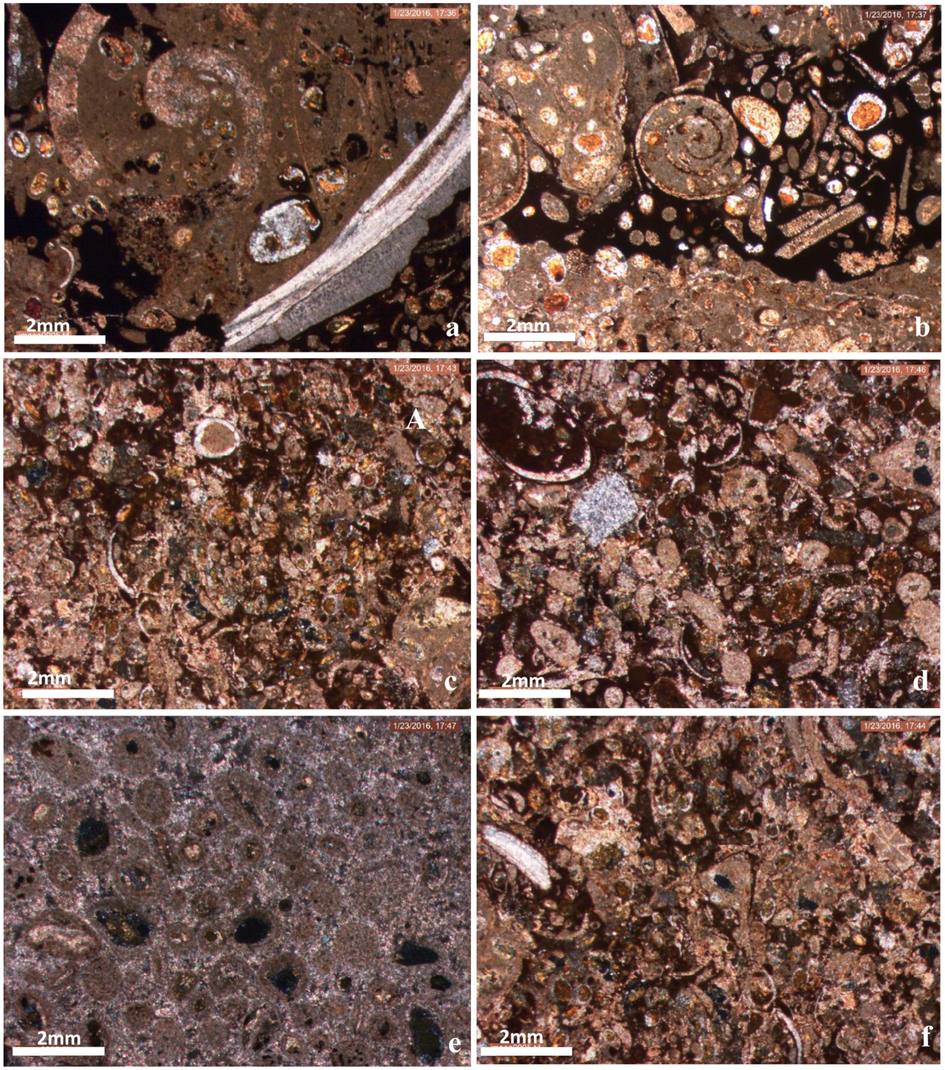

Examples of the microfacies analyses of the Sinn El-Kaddab section. A: Bioclastic wackestone/packstone with planktonic foraminifera and shell fragments, lower part of the section. B: Echinoidal bioclastic packstone/grainstone with echinoid plates and spines, upper part of the section. C: Bioclastic floatstone with pesoids, lower part of the section. D: Bioclastic grainstone, lower part of the section. E: Bioclastic wackestone with planktonic foraminifera, lower part of the section. F: Bioclastic wackestone/packstone with mostly recrystallized shell fragments, upper part of the section.

6 Results

6.1 Microfacies analysis

The Kurkur Formation thin sections from the Garra section north of the study region contained bioclastic oolitic packstones and packstones/grainstones (Figs. 2a and 6). The predominant skeletal grains include primarily of bivalves, echinoids, gastropods, bryozoans, foraminifera, corals, and ostracods. The non-skeletal grains in the top section are characterized by phosphatic and glaucanitic patches, as well as a small number of ooids. All grains are encased within micrite and microsparite in certain areas. The cavities of corals, gastropod whorls, and foraminifera chambers contain micrite and internal sediments. The walls of the ostracod and bryozoan have undergone recrystallization (Fig. 10). The primary microfacies types found in the Wadi Abu Sayalcarbonates are bioclastic oolitic packstones/grainstones, floatstones, and grainstones (Figs. 3a and 7). The skeletal grains consist of bioclasts and biomorphs derived from ostracods, bivalves, gastropods, echinoids, and foraminifera. Non-skeletal grains primarily consist of carbonate nuclei in the form of ooids and pisoids. The primary diagenetic changes that occur in these microfacies types include micritization and silicification of certain ooids, as well as recrystallization of other skeletal grains.

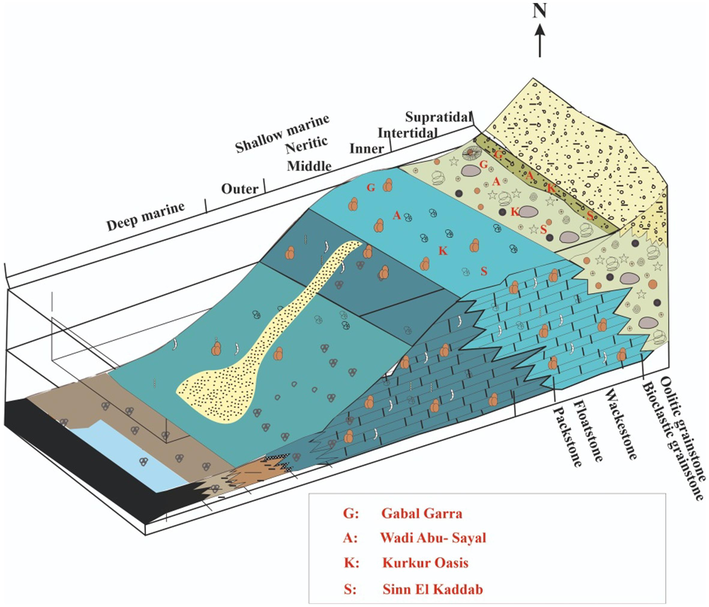

Depositional model with the range of MF types and distribution of biogenic components on a carbonate platform for the mixed siliciclastic/carbonate facies of Kurkur Formation.

The carbonate samples collected from the Kurkur Oasis area contained bioclastic oolitic wackestones, wackestones/packstones, packstones, and floatstones (Figs. 4a and 8). The skeletal grains consist of echinoid plates and spines, gastropods, bivalves, brachiopods, and corals. Certain grains exhibit diagenetic characteristics such as recrystallization, micritization, and stylolites, while others have maintained their initial structures. The non-skeletal grains consist of oolitic grains, phosphatic pellets, and tiny, subrounded quartz grains. The oolitic grains are of small to medium size and have a rounded to subrounded shape. They also include carbonate nuclei. The interstitial material between the grains consists of micrite, which transitions to microsparite in certain areas. The examination of carbonate samples from the Sin El-Kaddab section located south of the study region identified many types of sedimentary rock compositions. These include bioclastic packstones, packstones/grainstones, wackestones, wackestones/packstones, and floatstones (Figs. 5a and 9). The bioclastic grains consist of echinoid plates and spines, as well as fragments of bivalves, gastropods, foraminifera, ostracods, and scleractinian corals. The skeletal grains are primarily enclosed within the micritic matrix and serve as vital components in the formation of the rock. The majority of the skeletal grains underwent recrystallization and micritization, whereas a small number were silicified. The echinoid fragments exhibit syntaxial overgrowth. The inside chambers of gastropods, foraminifera, and ostracods are filled with sediments, micrite, phosphate pellets, and other minute skeletal grains. The non-skeletal grains are found as phosphatic pellets made of apatite, making up 5–10 % of the total grain volume.

6.2 Faunal content of Kurkur Formation

The Kurkur Formation displayed variations in lithology and thickness over the study area, progressing from north to south. The thickness progressively augments as one moves towards the south. The thickness measurements in Gebel Garra, Wadi Abu-Sayal, Kurkur Oasis, and Sinn El-Kaddab sections are 6 m, 6 m, 10 m, and 20 m respectively.

The present study documented the foraminiferal assemblages found in the Kurkur Formation. These include Anomalinoides spp., Lagena sp., miliolides, Textularia cf. farafraensis, Vaginulinopsis midwayana, Vaginulina trilobata, Spiroloculina tenuis, Alabamina midwayensis, and Pseudonodosaria manifesta in the lower part of the formation. In the upper part, the following taxa were recorded: Haplophragmoides spp., Ammobaculites spp., and Cribrostomoides cretacea (Figure 11 supplementary).

The foraminiferal species found to the north of the research region in the Gebel El-Borga section are as follows: Ammobaculites subcretaceus, Trochammina diagonis, Bathysiphon arenaceous, Spiroplectoides clotho, and Ammobaculites texanus were documented by Hewaidy and Soliman in 1993. The Kurkur Formation, located between G. Garra and Barqat Kurkur, is characterized by the presence of the following taxa: Ammobaculites, Haplophragmoides, Textularia, Spiroplectammina, Eponides, Alabamina, Cibcidoides, Quinqueloculina, and Spiroloculina (Hewaidy 1994). The documented fauna is characterized by abundant echinoids, gastropods, pelecypods, cephalopods, and crustaceans. The Kurkur Formation at southwest Aswan contains several macrofossils, namely Modiolus kurkurensis, Felaniella (Zemysia) pygmea, Paraglans altirostris, Phaxas antiquus, and Caryocorbula kurkuriana (Strougo and Hewaidy 1993).

7 Discussion

7.1 Depositional environments

The Kurkur Formation displayed variations in rock type and thickness across the research area, progressing from north to south. As stated in section 4, the thickness progressively increases towards the south, reaching 6 m, 6 m, 10 m, and 20 m at the Gebel Garra, Abu-Sayal, Kurkur Oasis, and Sinn El-Kaddab portions respectively. The depositional environments of the Kurkur Formation were determined by analyzing the microfacies, which showed a transition from wackestones, floatstones, and packstones in the lower part to oolitic and bioclastic grainstones. The foraminifera assemblages, especially the calcareous types, were studied throughout the sequence, with an increase in arenaceous assemblages towards the uppermost part. Additionally, the presence of bivalves, gastropods, and echinoids provided insights into the macrofossil content. Furthermore, the analysis conducted by Flügel, 2010 was taken into account. It revealed that sedimentation on shelves frequently leads to the formation of sequences that gradually get shallower over time, with the rates of subsidence and sea-level rise playing a significant role in this process. Consequently, the upper parts of these sequences exhibit indications of being exposed to both intertidal and supratidal conditions. Based on the findings, it can be concluded that the Kurkur Formation in the examined sections was likely deposited in a middle neritic zone in the lower portions and transitioned to an inner neritic environment that eventually became a supratidal zone in the upper portions.

7.1.1 Middle neritic environment

The depositional environment in question, found in the lower portion of the four examined sections, consists of fossil-rich limestone including glauconite, as well as benthic and planktonic foraminifera, ostracods, and a small number of megafossils. The thin sections obtained from this bottom layer exhibit a plentiful presence of wackestones, floatstones, and packstones, with a small number of packstones/grainstones. This environment is limited at the bottom by a sequence boundary, which is indicated by a regional unconformity documented at the Cretaceous-Paleocene boundary (Hewaidy 1990). Furthermore, it intersects the upper section of the Dakhla/Kiseiba Formation instead of being located at the bottom of the Kurkur (Hewaidy 1994; Tantawy et al. 2001). The regional unconformity aligns with the boundary between the Kiseiba/Kurkur or Dakhla/Kurkur formations. It is characterized by the lack of the most recent Maastrichtian planktonic (CF2) and (CF1) biozones, as well as the earliest Paleocene planktonic (P1a) and (P1b) biozones. This phenomenon seems to be primarily associated with a significant decrease in sea level, and secondarily with local tectonic movements linked to the Bahariya arch (Tantawy et al. 2001; Hewaidy et al. 2016). The field and microfacies investigations revealed the presence of a shelf lagoon characterized by open circulation below the wave base. The particles were generated in a high-energy environment on shallow areas and then moved down nearby slopes before settling in calm water (Flügel 1982). This is associated with facies zone 7 and the typical microfacies types 8, 9, and 10 as described by Wilson (1975) and Flügel (1982).

The lower section of the Kurkur Formation is believed to have had an intermediate neritic environment that coincided with the start of the Paleogene transgression in the research area, as proposed by Hewaidy and Soliman in 1993. The presence of a foraminiferal assemblage with a low ratio of planktonic to benthonic organisms, along with the presence of macrofossils and the occurrence of oolitic sandy and shaly sediments, suggests that the Kurkur Formation was deposited in an open, shallow inner shelf environment (Hewaidy 1994). The documented assemblage of foraminifera is considered as being from an inner-middle neritic to lagoonal habitat (Luger 1988; Aref and Youssef 2004). The lower section of the Kurkur formation was formed in shallow to moderately deep marine environments, as shown by the presence of benthic foraminifera, as reported by Hewaidy et al. in 2014. The high-stress environment in southern Egypt during the Maastrichtian-Paleocene period was mainly caused by the shallow shelf conditions, as well as local tectonic activity and restricted circulation, as stated by Hewaidy et al. (2016).

7.1.2 Inner neritic to supratidal environment

The depositional environment is represented by the middle and top portions of the four sections that were investigated. The composition consists of yellow to brown dense sandy oolitic limestone with occasional thin layers of phosphatic limestone. This sequence contains a variety of fossils, including scattered oyster shells, gastropods, echinoids such as Gitolampas abundanas Mayer Eymer, brachiopods, and corals. The microfacies types present in large quantities include packstones, grainstones, and packstones/grainstones with shell pieces, benthic foraminifera, ostracods, and phosphatic pellets. Hewaidy and Soliman (1993) proposed that the upper part of the formation corresponds to a shallow shelf to supratidal environment, as shown by its lithological and paleontological features. A study by Luger (1985), Youssef (2003), and Hewaidy et al. (2014) proposed the existence of a shallow shelf environment with high salt concentration. In this environment, the following species were found in the Kurkur Formation: Ammobaculites spp., Haplophragmoides spp., Trochammina spp., Anomalinoides sp., and miliolides. Microfacies analyses revealed that oolite shoals and tidal bars were subjected to a vigorous environment characterized by continuous wave action at or above the wave base (Flügel 1982). This is associated with facies zone 6 and the specific microfacies types 11, 12, and 15 as defined by Wilson (1975) and Flügel (1982). This geological zone is distinguished by the lack of planktonic foraminifera and the prevalence of Trochammina rainwateri biofacies, indicating a shallow inner neritic habitat. The composition consists of green gypsiferous shale that is interspersed with a brown argillaceous limestone band (see Fig. 8). A depositional model for the different microfacies in the study area shown in Fig. 10.

8 Conclusion

The analysis of carbonate rocks from the lower portion of the middle to early late Paleocene Kurkur Formation at the Gebel Garra, Abu-Sayal, Kurkur Oasis, and Sinn El-Kaddab sections in the Southwestern Desert showed a significant presence of wackestones, floatstones, and packstones, with a few packstones/grainstones. In contrast, the upper portion contained a large amount of packstones, packstones/grainstones, and grainstones. The lower section of the Kurkur Formation has carbonate deposits that contain a variety of fossils, including benthic and planktonic foraminifera, ostracods, and a small number of macrofossils. The upper section contains a variety of fossils, including dispersed oyster shells, gastropods, echinoids, brachiopods, benthic foraminifera, ostracods, and corals. Based on the analysis of microfacies and fossil material, it can be determined that the Kurkur Formation in the study region was deposited in intermediate neritic habitats. In the lower section, it was below the wave base, but as it moved upwards, it transitioned to shallow shelf and supratidal environments that were at or above the wave base.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Mohamed Youssef: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Abdelbaset El-Sorogy: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Data curation. Bassam A. Abuamarah: Project administration, Investigation. Mahmoud Hefny: Writing – review & editing, Software, Methodology. Saida A. Taha: Software, Methodology, Data curation.

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to Researchers Supporting Project number (RSPD2024R1044), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- The benthic foraminifera perturbation across the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum event (PETM) from Southwestern Nile Valley, Egypt. Neues Jahrbuch Für Geologie Und Paläontologie-Abhandlungen. 2004;234(1–3):261-269.

- [Google Scholar]

- Berggren, W., Kent, D., Swisher, C. Aubry, M. (1995), “A revised Cenozoic Geochronology and Chronostratigraphy”. In Berggren et al. (Eds.) Geochronology, time scales and global stratgraphic correlation, SEPM special publication, 54: 129-212.

- Neues zur Geologie und Paleontologie Aegyptens. II: Das Palaeogen. Z. Dtsch. Geol. Ges.. 1900;52:403-479.

- [Google Scholar]

- Classification of carbonate rocks according to depositional texture. In: Ham W.E., ed. Classification of carbonate rocks. AAPG Memoirs; 1962. p. :108-121.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nannofossil biostratigraphy of the type locality of the Garra El Arbain facies, southwest Aswan, Egypt. Egypt. J. Geol.. 1995;39:361-375.

- [Google Scholar]

- Microfacies analysis of limestones. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1982. p. :633.

- Microfacies of carbonate rocks, analysis, interpretation and application. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer-Verlag; 2010. p. :976.

- Stratigraphical and sedimentological framework of the Kharga-Sinn El Kaddab stretch (western and southern part of the upper Nile Basin), Western Desert, Egypt. Berlilner Geowissenschaftliche Abhandlungen. 1984;50:117-151.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evolution of the depositional environments of SE-Egypt during the Cretaceous and Lower Tertiary. Berliner Geowissenschaftliche Abhandlungen. 1987;A75(1):49-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- Stratigraphy and paleobathymetry of Upper Cretaceous-Lower Tertiary exposures in Beris-Doush area, Kharga Oasis, Western Desert, Egypt. Qatar University Science Bulletin. 1990;10:297-314.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biostratigraphy and paleobathymetry of the Garra-Kurkur area, southwest Aswan, Egypt. Middle East Research Center, Ain Shams University, Earth SciencE, Series. 1994;8:48-73.

- [Google Scholar]

- Paleocene gastropods and nautiloids of southwest Aswan, Egypt. Egypt Journal of Paleontology. 2002;2:199-218.

- [Google Scholar]

- Maastrichtian to Paleocene agglutinated foraminifera from the Dakhla Oasis, Western desert, Egypt. Egyptian J. Paleontol.. 2014;14:1-38.

- [Google Scholar]

- Stratigraphy and paleoecology of Gebel El. Borga, south-west Kom Ombo, Nile Valley, Egypt. Egypt. J. Geol.. 1993;37(2):299-321.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sequence stratigraphy of the Maastrichtian-Paleocene succession at the Dakhla Oasis, Western Desert, Egypt. J. Afr. Earth Sc.. 2016;136:1-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Review of Upper Cretaceous-Lower Tertiary stratigraphy in central and southern Egypt. Bulletin of the American Association of Petroleum Geology. 1972;56:1448-1463.

- [Google Scholar]

- Stratigraphie der marinen Oberkreide and des Alttertiarsim sudwestlichen Obernil-Becken (SW-Agypten) unter besonderer Berudcksichtigung der Mikropalaontologie, Pal kologie.und Paläogeographie. Berlilner Geowissenschaftliche Abhandlungen. 1985;63:1-151.

- [Google Scholar]

- Maastrichtian to Paleocene facies evolution and Cretaceous/Tertiary boundary in Middle and Southern Egypt. Revista Espanola De Paleontologia, N.o Extraordinario 1988:83-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Stratigraphy of the Late Cretaceous-Early Tertiary sediments of Sinn El Kaddab-Wadi Abu Ghurra stretch, southwest of the Nile Valley, Egypt. the Cretaceous of Egypt. Geological Society of Egypt Special Publications. 1996;No. 2

- [Google Scholar]

- Planktic foraminifera from the mid-Cretaceous (Barremian–Early Albian) of the North Sea Basin: Palaeoecological and palaeoceanographic implications. Mar. Micropaleontol.. 2006;58(2):83-102.

- [Google Scholar]

- Scanning electron and light microscopic investigations of angiosperm pollen from the Lower Cretaceous of Egypt. Pollen Spores. 1983;25:213-242.

- [Google Scholar]

- On some Kurkurian bivalves from southwest Aswan. Middle East Research Center, Ain Shams University, Earth Science, Series. 1993;7:190-208.

- [Google Scholar]

- Maastrichtian to Paleocene depositional environment of the Dakhla Formation, Western Desert, Egypt: sedimentology, mineralogy, and integrated micro- and macrofossil biostratigraphies. Cretac. Res.. 2001;22:795-827.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tantawy, A. (1994), “Paleontological and sedimentological studies on the Late Cretaceous/Early Tertiary succession at Wadi Abu Ghurra–Gebel El Kaddab stretch, South Western Desert, Egypt”, Master of Science Thesis, Aswan Faculty of Science, Assiut University, Egypt.

- Carbonate facies in geologic history. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1975. p. :456.

- The calcareous nannofossil turnover across the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum Event (PETM) in the southwestern Nile Valley, Egypt. Neues Jahrbuch Für Geologie Und Paläontologie-Abhandlungen. 2004;234(1–3):291-309.

- [Google Scholar]

- Youssef, M. (2003), “Micropaleontological and stratigraphical analyses of the Late Cretaceous/Early Tertiary succession of the Southern Nile Valley (Egypt)”, Ph.D. Thesis, Ruhr-Universität Bochum, Germany. 197 pp.

Appendix A

Supplementary material

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2024.103347.

Appendix A

Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article: