Corn oil based cinnamate amide/Fe2O3 nanocomposite anticorrosive coating material

⁎Corresponding author. maalam@ksu.edu.sa (Manawwer Alam)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Objectives

The efforts are being focused to utilise sustainable resources such as vegetable oils, which are amenable to chemical transformations producing monomers and polymers yielding protective coatings. The present manuscript describes the preparation of nanocomposite coatings from corn oil (CO).

Methods

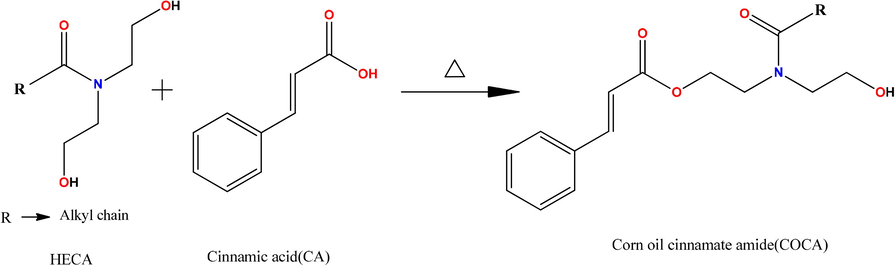

CO was subjected to amidation followed by esterification by cinnamic acid producing CO cinnamate-amide (COCA). COCA was next enriched with Fe2O3 nanoparticles (COCA/ Fe2O3) and crosslinked with phenol formaldehyde to produce polymeric coatings on mild steel panels.

Results

COCA obtained was rich in functional groups: benzene ring, conjugated with an acrylic group, ester and amide functional group with pendant alkyl chain, and terminal hydroxyl group. The multiple functional groups and nanoparticles offered good adhesion, scratch resistance and flexibility to the resulting nanocomposite coatings. COCA/Fe2O3 coatings showed good physico-mechanical properties and corrosion resistance performance in 3.5 wt% NaCl medium and can be safely used upto 225 °C.

Keywords

Corn oil

Cinnamic acid

Coatings

Corrosion

1 Introduction

The sustainable and green processes and products are the continuous demands of coatings industry worldwide. The utilization of renewable raw materials such as vegetable oils, lignin, cellulose, chitosan, starch and others in the field of coatings has been in trend, of late (Pourhashem, 2020; Rather et al., 2022). Vegetable oils (VO) are cheaper, abundantly available, environment friendly and are rich in functional groups that are amenable to several chemical transformations such as epoxidation, hydroxylation, esterification, amidation, urethanation and others. Thus, VO are derivatized as epoxies, polyols, esters, ester-amides, ether-amides, urethanes and are widely formulated into coatings and paints (Sharmin et al., 2015). The introduction of functional groups such as ester, amide, urethane and others in VO coatings’ backbone contributes good acid, alkali resistance to the coatings, improves drying behavior, mechanical strength, and adhesion of the coatings (Zhang et al., 2017), which can be further augmented by the development of VO based nanocomposites (Ghosal and Ahmad, 2017; Ghosal et al., 2019; Ghosal et al., 2015).

Corn oil (CO) predominantly consists of linoleic acid, along with tocopherols and phytosterols. The worldwide production of CO is about 2.4 million metric tons annually (Ni et al., 2016). In the past, CO has been used to develop ether, ester, amide and urethane functional group incorporated coatings (Alam and Alandis, 2014; Alam et al., 2017). These coatings have shown good physico-mechanical properties and flexibility retention characteristics as well as good adhesion performance. CO coatings comprising of urethane, ester, ether or amide functional groups, reinforced with fumed silica have shown good anticorrosion performance in 3.5 wt%NaCl solution after several days of exposure (Alam, 2019; Alam et al., 2020). In another work, epoxidized CO incorporating silane (-Si-OCH2CH3) groups has been used to fabricate hydrophobic and moisture-resistant coating for paper substrate (Thakur et al., 2019).

Cinnamic acid (CA) is a phenolic compound obtained from the cinnamon bark, with a double bond and acrylic acid functional group, which render it suitable for severable modifications (Ruwizhi and Aderibigbe, 2020). It is used as an antioxidant and antimicrobial agent in coatings to protect food and conserve shelf life (Cai et al., 2019; Letsididi et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2019). It has been categorized as “Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) compound”. CA coatings on kiwi fruits, melon slices, pears, tomatoes have extended their shelf-life (Adeniji et al., 2020; Azmai et al., 2019; Sharma and Rao, 2015).

Iron oxide nanoparticles have been used as pigments and as anticorrosive agents in several polymeric coatings. Jeyasubramanian et al developed Fe2O3 /alkyd nanocomposite coatings for industrial applications (Jeyasubramanian et al., 2019). Dhoke et al studied the electrochemical behavior of Fe2O3/ alkyd coatings exposed to 3.5 wt% NaCl for several days that were abrasion and scratch resistant and had shown UV-blocking properties (Dhoke et al., 2009). Rahman and Ahmad prepared Fe2O3/Soy alkyd nanocomposite coatings cured with melamine formaldehyde, that exhibited good thermal stability and hydrophobicity, enhanced physico-mechanical performance and corrosion inhibition of carbon steel (Rahman & Ahmad, 2014).

In this research work, CO was derivatized as amide diol followed by esterification with CA producing CO cinnamate-amide (COCA). COCA was reinforced with nanosized Fe2O3 (COCA/ Fe2O3) to prepare COCA nanocomposite. COCA and COCA/ Fe2O3 were cured with phenol formaldehyde, applied on mild steel panels, to prepare coatings. COCA and COCA/ Fe2O3 coatings were subjected to physico-mechanical and corrosion resistance in saline medium. COCA/ Fe2O3 coatings performed well relative to COCA coatings in terms of their physico-mechanical and corrosion resistance performance. COCA/ Fe2O3 showed higher thermal stability and can be safely used upto 225 °C. The approach can be considered as relatively greener and environmentally safe since we have attempted to develop a relatively greener material, without the formation of any side product or wastes, and by using renewable resources (CO and CA) (Alam et al., 2020b).

2 Materials

Corn oil [CO] (Afia International Company, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia), diethanolamine, sodium metal, sodium chloride, cinnamic acid [CA] (Analytical grade, BDH Chemicals, Ltd. Poole, England), iron oxide [Fe2O3] nanoparticles (size 28–32 nm, Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany), phenol formaldehyde [PF] (Synthetic & Polymer Industries, Ahmadabad, Gujarat, India) were used as received.

2.1 Synthesis

2.1.1 Synthesis of N,N’ bis-2-hydroxyethyl corn amide [HECA]

HECA was prepared according to a our previously reported method (Alam and Alandis, 2014; Alam et al., 2020a).

2.1.2 Synthesis of COCA

HECA (0.08 mol, 28 g) and CA (0.08 mol, 11.85 g) were placed over a magnetic stirrer, in three-necked flask equipped with condenser, thermometer, and 1 ml sulfuric acid (1:1 diluted in distilled water) was added dropwise to the reaction mixture under stirring. The contents were heated and stirred at temperature 150 °C for 6 h. The reaction was monitored by FTIR at regular intervals until FTIR confirmed the formation of COCA.

2.1.3 Synthesis of COCA/ Fe2O3 nanocomposite

To COCA was added Fe2O3 nanoparticle (1 wt%; based on the weight of HECA) and mixed thoroughly at room temperature for1h, yielding COCA/ Fe2O3 nanocomposite.

Both COCA and COCA/ Fe2O3 nanocomposite were treated with PF to produce thermally stable, crosslinked thermoset coatings on mild steel (MS) panels as described in proceeding section.

2.2 Preparation of coatings

The mild steel panels of appropriate sizes and shapes (circular panels, diameter 1 cm, thickness 150 µm for SEM analysis; 70mmX25mmX1mm for physico-mechanical and gloss measurements of coatings; 25mmX25mmX1mm for corrosion tests) were cleaned by rubbing with polishing paper, then degreased by washing with double distilled water, methanol and acetone, one by one, and followed by drying in an oven. COCA and COCA/Fe2O3 were treated with phenol formaldehyde [PF], applied by brush on clean mild steel panels and then placed in hot air oven at different temperatures for different time periods and at different loading of PF (at 45,50,55 phr), to ascertain the appropriate drying temperature, time and loading (phr) of PF that could result in the formation of adequate coating material.

The ideal curing/drying temperature and time period was found as 200 °C, 3 h for COCA and 180 °C, 3 h for COCA/Fe2O3 nanocomposite at 45phr loading of PF.

2.3 Characterization

The spectral analyses of the samples were recorded on FTIR spectrophotometer (Spectrum 100,Perkin Elmer Cetus Instrument, Norwalk, CT, USA) and Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) (1H NMR and 13C NMR; JEOL DPX400MHz, Japan) using deuterated chloroform and dimethyl suphoxide as solvents and tetramethylsilane as internal standard. X-ray analysis was performed on X-ray Powder Diffractometer (XRD) ULTIMA IV, RIGAKU Inc, Japan. The morphology was studied by Transmission electron microscopy (JEOL JEM, 2010; Hitachi, Japan), Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM; JSM 7600F, JEOL, Japan.) and Energy dispersive X- ray spectroscopy (EDX; Oxford, UK. Acid value: AV (ASTM D555–61). XPS spectrometer (JEOL, JPS-9030, Japan) was used with a Mg Kα (1253.6 eV) X-ray source at 10 mA and 12 kV in ultrahigh vacuum (<10−7 Pa) to quantify the surface and functional groups of developed materials. Thermal stability of COCA and COCA/Fe2O3 were assessed by thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) (Mettler Toledo AG, Analytical CH-8603, Schwerzenbach, Switzerland).

Thickness measurements (ASTM D 1186-B), scratch hardness test (BS 3900), crosshatch (ASTM D3359-02), pencil hardness test (ASTM D3363-05), impact resistance test (IS 101 part 5 s-1,1988), flexibility/bending test (ASTM D3281-84), gloss (Gloss meter, Model: KSJ MG6-F1, KSJ Photoelectrical Instruments Co., ltd. Quanzhou, China), and contact angle measurements (CAM200 Attention goniometer) were performed by standard methods.

For corrosion resistance test, the specimens were attended as working electrode. An exposed surface area of 1.0 cm2 was fixed by PortHoles electrochemical sample mask, with Pt electrode as counter electrode, and 3 M KCl filled Ag electrode as reference electrode (Auto lab Potentiostat/galvanostat, PGSTAT204-FRA32, with NOVA 2.1 software; Metrohom Autolab B.V. Kanaalweg 29-G, 3526 KM, Utrecht, Switzerland).

3 Results and discussion

VO contains various functional groups that can be chemically transformed producing different types of monomers and polymers. To increase the functional attributes and enhance applicational value of CO, it was chemically transformed into amide diol [HECA] by amidation reaction, resulting in HECA monomer which contained two hydroxyl groups, an amide group and long hydrocarbon chain. The hydroxyl group of HECA reacted with carboxylic group of CA, by condensation reaction (Scheme 1), introducing ester functional group, producing cinnamate amide of CO [COCA]. COCA contained a benzene ring, conjugated with an acrylic group, ester and amide functional group with pendant alkyl chain, and terminal hydroxyl group. Thus, COCA had plurality of functional groups, however it needed to be polymerized/crosslinked to obtain thermoset coating material. Thus, to obtain polymeric coating material from COCA, it was treated with PF and baked in oven at appropriate temperature for desirable time period. Further, in another reaction, COCA was reinforced with Fe2O3 nanoparticles and treated with PF, to further enrich COCA with adequate physico-mechanical and corrosion protective properties and to obtain thermally stable, crosslinked nanocomposite polymeric coatings (Jadhav et al., 2011).

- Synthesis of COCA.

HECA, COCA and COCA/ Fe2O3 nanocomposite were subjected to spectral analysis for structure elucidation, morphology and thermal stability analysis, as well as to investigate their coating performance.

3.1 Spectral analysis

To elucidate the structure of HECA, COCA and COCA nanocomposite, it is necessary to study the spectral analysis of CO which has been described in our previous publication (Alam and Alandis, 2014). FTIR spectrum of CO shows the presence of absorption bands at 3008 cm−1, 2926 cm−1, 2854 cm−1, 1746 cm−1, 1654 cm−1, 1238 cm−1, 1163 cm−1 and 1100 cm−1 corresponding to -C—H stretching absorption bands of carbon–carbon double bonds, –CH2 and –CH3 (sym and asym str), >C⚌O (ester), -C⚌C- and > C(=O)-O- (ester) absorption bands. FTIR spectrum of HECA showed the presence of bands of hydroxyl at 3425 cm−1, and amide (>C⚌O and-CN-) at 1623 cm−1 and 1464 cm−1, respectively, along with the presence of the functional group absorption bands as in CO. FTIR spectrum of HECA has not shown the presence of > C⚌O (ester) absorption band, which had occurred as a prominent band in CO, because > C⚌O (ester) of CO was consumed during amidation reaction, which had resulted in the appearance of amide bands (>C⚌O and -C—N) and hydroxyl bands in HECA.

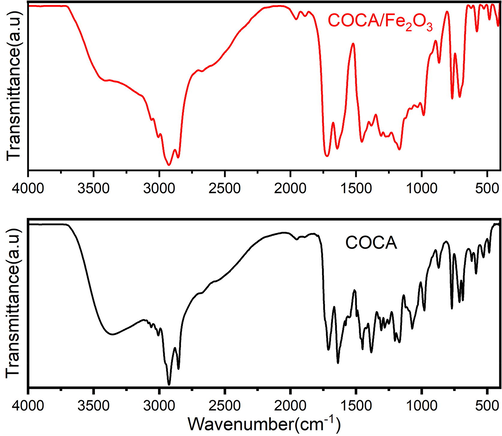

FTIR spectrum of COCA showed the band appearing at 1711 cm−1 for ester group and the bands for hydroxyl functional group appeared at 3357 cm−1 as a depressed band relative to that in HECA, which confirmed the introduction of ester by reaction with hydroxyl group. Additional bands appeared for amide bands (>C⚌O and -C—N) at 1638 cm−1 and 1450 cm−1. The introduction of benzene ring of CA is confirmed by the presence of new bands at 3061 cm−1 (Ar-C⚌C–H), 1579 cm−1, 1496 cm−1, 770 cm−1 and 686 cm−1 (Ar-C⚌C–H). The broad absorption band for hydroxyl group supported that these occur as hydrogen bonded groups. In the FTIR spectrum (Fig. 1) of COCA/Fe2O3, when compared with the spectrum of COCA, absorption band for hydroxyl appears suppressed, amide bands (>C⚌O and -C—N) are observed at 1642 cm−1 and 1455 cm−1, and ester group at 1718 cm−1, that support the interaction of COCA functional groups with nanoparticles (Alam et al., 202a,b).

- FTIR spectra of COCA and COCA/Fe2O3 nanocomposite.

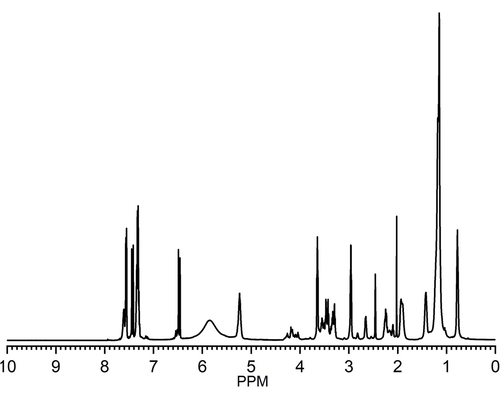

1H NMR spectrum (Fig. 2) of COCA showed peak for OH (5.8 ppm) and for –CH2OH (3.28–3.50 ppm). The peak for –CH = CH– as in HECA (Alam and Alandis, 2014) appeared at 5.23–5.24 ppm, while additional peak beyond 5.60 ppm is correlated to –CH = CH– of CA. The peaks are also observed at 4.0–4.4 ppm (–CH2—O—C(=O)-), 3.63–3.65 ppm (-N-CH2-CH2—O—C(=O)-), 3.41–3.48 ppm (-N-CH2-CH2-OH), 2.95–2.97 ppm (-N-CH2-CH2-OH), 2.23–2.26 ppm (–CH2-C(=O)-N-), 2.02 ppm (CH2 attached to double bond), 1.15–1.42 ppm (CH2), 0.77–0.78 ppm (CH3).

-

1H NMR spectra of COCA.

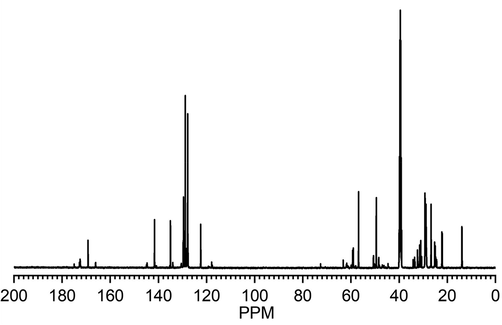

13C NMR spectrum (Fig. 3) of COCA showed peaks at 172.76 (>N-C⚌O), 169.22 (>C = Oester), 122.43–135.00 ppm (carbons ArCA), 129.60–129.73 (–CH = CH–), 59.04–59.30 (>N-CH2CH2-OH), 48.49–49.49 (>N-CH2CH2-OH), 22.11–34.22 (CH2chain), 13.93(–CH3) that confirmed the formation of COCA by reaction with CA.

-

13C NMR spectra of COCA.

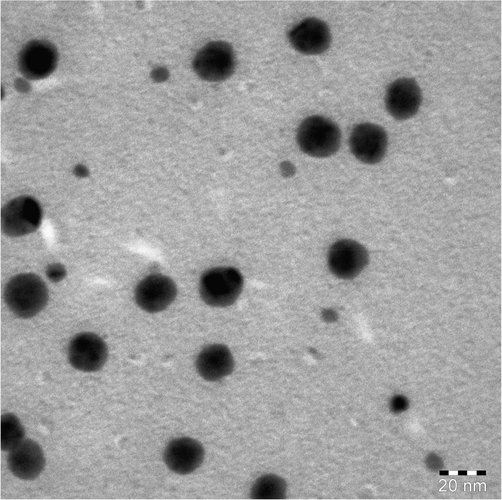

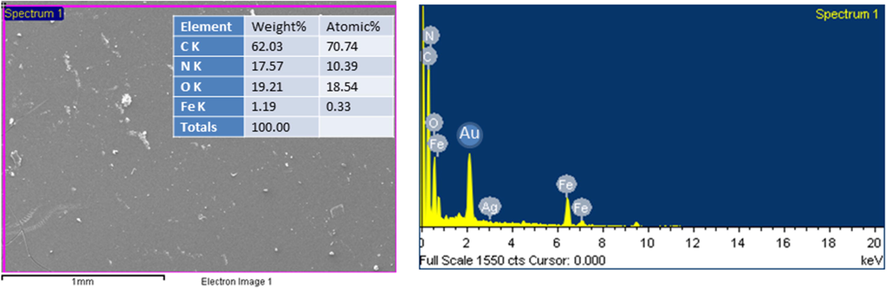

3.2 Morphology

TEM micrograph (Fig. 4) of COCA/Fe2O3 revealed the distribution of Fe2O3 of size 5–15 nm in COCA matrix. These nanoparticles can be observed as unagglomerated spherical particles with distinct boundaries, appearing as dark globules in grey COCA background. From the SEM micrograph (Fig. 5) of COCA/Fe2O3 coating, it is evident that there are no cracks or pinholes in the coating and it appears free from any defects. The EDX (Fig. 5) peaks belonging to C (62.03 %), N (15.57 %), O (19.21 %) and Fe (1.19 %) were seen and confirmed the presence of Fe2O3 in COCA/Fe2O3.

- TEM of COCA/Fe2O3 nanocomposite.

- SEM-EDX of COCA/Fe2O3 nanocomposite.

XRD Analysis: XRD pattern of COCA and COCA/Fe2O3 nanocomposite are similar because Fe2O3 nanoparticles are embedded within the polymer matrix of COCA so that COCA and COCA/Fe2O3 are shown amorphous in nature. XRD pattern has not shown any remarkable difference in presence of Fe2O3 in COCA (Fig. S1).

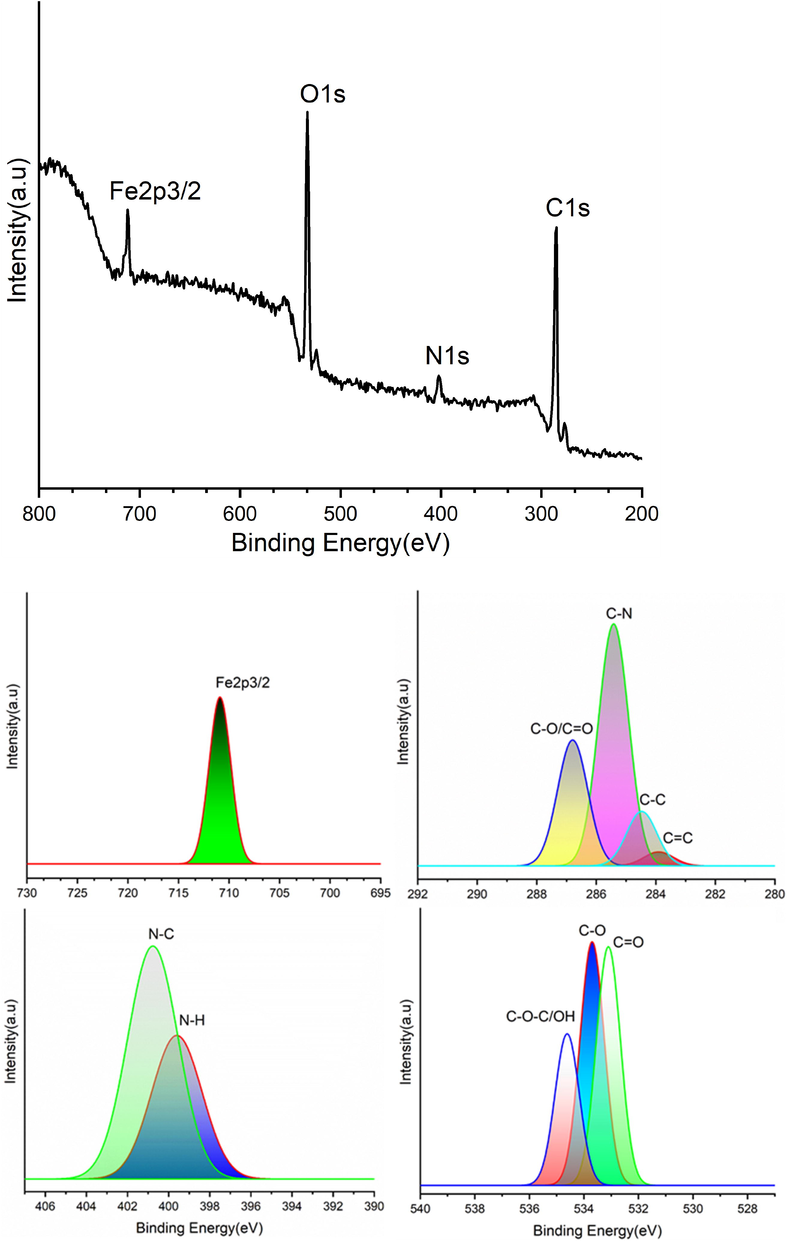

XPS Analysis: The surface composition of COCA/Fe2O3 nanocomposite was analysed by XPS that showed the deconvoluted peaks of COCA/Fe2O3: C1s, N1s, O1s, and Fe 2p as evident in Fig. 6 and also summarized below, with respective binding energies that supported the structure of COCA/Fe2O3 nanocomposite (Ghosh and Karak, 2020; Zhu et al., 2017): carbons [283.89(C⚌C), 284.45(C—C), 285.41(C—N), 286.84 (C—O/C⚌O)], nitrogens [399.56(N—H), 400.79(N—C)], oxygens [533.09 (C⚌O), 533.71 (C—O)], 534.61C-O/OH, Fe [Fe2p3/2 (710.96 eV)].

- XPS of COCA/Fe2O3 nanocomposite(survey and deconvoluted).

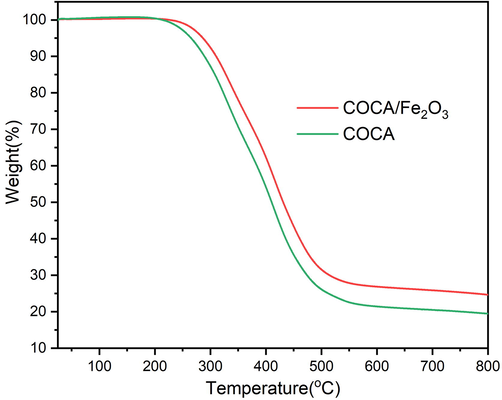

3.3 Thermogravimetric analysis

DTG thermograms of COCA and COCA/Fe2O3 (Fig. S2) displayed two endothermic events: from 300 °C to 350 °C, followed by the next event until 500 °C, which corresponds to the thermal degradation stages that are however not distinct in TGA (Fig. 7). The thermal stability of COCA/Fe2O3 was found to be improved compared to COCA due to the homogenous dispersion of Fe2O3 nanoparticles in COCA matrix. TGA thermogram showed that 5 wt% loss occurred at 262 °C and 286 °C in COCA and COCA/Fe2O3, respectively. In COCA and COCA/Fe2O3, 20 wt%, 50 wt% and 75 % losses occurred at 326 °C, 410 °C and 501 °C and 345 °C, 431 °C and 700 °C, respectively. Both COCA and COCA/Fe2O3 showed variation in thermal degradation temperatures, however, the degradation pattern/ramp of both remained the same.

- TGA thermogram of COCA and COCA/Fe2O3 nanocomposite.

3.4 Coating properties

COCA/Fe2O3 coating showed improved physico-mechanical properties and hydrophobicity compared to the plain COCA coating (Table 1). The nanocomposite coating showed improved scratch hardness (3.2 kg), pencil hardness (3H) and cross hatch adhesion test (100 %) compared to COCA coating. COCA/Fe2O3 coating was more flexibility retentive as it passed 1/8 in. conical mandrel bend test than COCA that failed the said test, however, both the coatings passed impact resistance test (100 lb/inch). The improved performance of the nanocomposite coating over its plain counterpart can be attributed to the presence of nanoparticles. The contact angle (Fig. S3) measurements were performed on the coated panels to ascertain their hydrophobic nature. COCA/Fe2O3 coating showed contact angle value (79°) which was relatively higher than in case of COCA (73°). Hydrophobicity of the coating plays an important role to combat the attack of corrosive media, by disallowing the seepage of corrosive ions. The higher contact angle value of nanocomposite coating evidently points towards the higher hydrophobicity characteristic of the nanocomposite coating that complements the overall coating performance in corrosive media.

| Properties | COCA | COCA/Fe2O3 |

|---|---|---|

| Scratch hardness(Kg) | 3.0 | 3.2 |

| Cross hatch | 97 | 100 |

| Pencil Hardness | 2H | 3H |

| Bending(1/8″) | fail | pass |

| Impact(100 lb) | pass | pass |

| Gloss at 60o | 90 | 95 |

| Thickness (microm) | 150 | 150 |

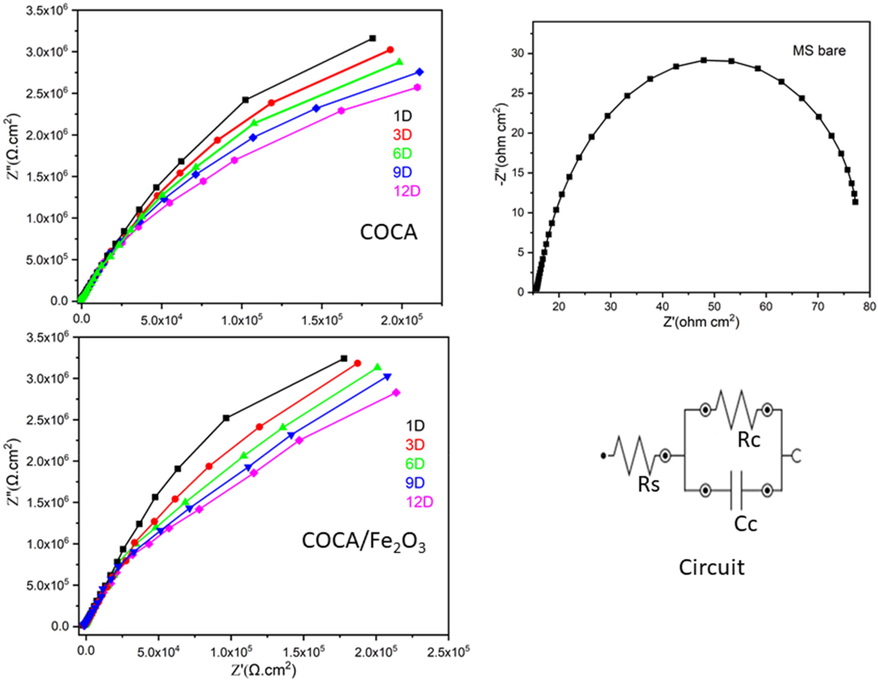

3.5 Electrochemical impedance spectroscopic studies

The electrochemical performance of the bare MS, COCA, and COCA/Fe2O3 nanocomposite coating panel immersed in 3.5 wt% NaCl solution is depicted in Fig. 8. It is seen that the maximum resistance is obtained for COCA/Fe2O3 nanocomposite coated MS as compared to COCA. Hence COCA/Fe2O3 nanocomposite showed better adhesion to the surfaces of bare MS. As the immersion days are increased, the decrease in resistance is observed due to permeation of corrosive ions through the coating artefacts. Fig. 8 displayed the equivalent circuit model which is used to fit the resultant Nyquist plots. EIS spectra fitted with corresponding parameters of the fitted graphs are shown in Table 2. The bare MS showed Rs, Rc value for one day immersion as 13.8 Ω, 9.28 KΩ, respectively, and Cc value 34.1pF. COCA coated MS and COCA/Fe2O3 nanocomposite MS displayed high Rs, Rc values as 768 Ω, 45.2MΩ and 786 Ω, 114 MΩ, and low Cc values as 111 pF, 114pF, respectively, for 1 day immersion. Hence, the results displayed less corrosion protection ability of COCA as compared to COCA/Fe2O3 nanocomposite coatings. The higher hydrophobicity of COCA/Fe2O3 does not allow the corrosive medium to pass through the coating material, while COCA coating being less hydrophobic is attacked by corrosive ions, leading to the formation of pores in the coating and reduced bonding strength of the coating with MS surface. The values of Rs, Rc after 12 days immersion decrease to 716 Ω, 51.3 MΩ (COCA) and 625 Ω, 35.0 MΩ (COCA/Fe2O3 nanocomposite) and Cc value increases to 122 pF (COCA), 126 pF (COCA/Fe2O3 nanocomposite). The enhanced Rs, Rc values and low Cc values are displayed for the COCA/Fe2O3 nanocomposite coated MS due to the uniform dispersion of nano Fe2O3 in COCA, which could contribute to the strong bonding formation to the metal interface, lock and key ability of nanoparticles to fill the pores in the polymeric structure, and oxidation stability of Fe2O3. Thus COCA/Fe2O3 nanocomposite provided superior adhesion to the MS interface as compared to COCA, resulting in the enhanced corrosion resistance of the coated MS for 12 days of immersion in NaCl solution.

- EIS spectra of COCA, COCA/Fe2O3 nanocomposite and bare MS in 3.5wt %NaCl solution.

|

Immersion Times (Days) |

Solution Resistance Rs(Ω) |

Coating resistance, Rc (Ω) x105 |

Coating Capacitance, Cc(pF) | χ2 | PE(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 768 | 45.2 | 114 | 1.80 | 99.97 |

| 3 | 742 | 38.2 | 116 | 1.59 | 99.97 |

| 6 | 697 | 38.0 | 124 | 1.35 | 99.97 |

| 9 | 694 | 37.6 | 125 | 1.76 | 99.97 |

| 12 | 625 | 35.0 | 126 | 1.60 | 99.97 |

| COCA/Fe2O3 nanocomposite coating | |||||

| 1 | 786 | 114 | 111 | 1.63 | 99.99 |

| 3 | 759 | 86.2 | 114 | 1.55 | 99.98 |

| 6 | 745 | 53.7 | 116 | 1.66 | 99.98 |

| 9 | 732 | 51.8 | 121 | 1.63 | 99.98 |

| 12 | 716 | 51.3 | 122 | 1.61 | 99.98 |

| Bare MS 1D |

13.8 | 0.0928 | 34.1 | 1.58 | – |

4 Conclusion

Corn oil based cinnamate-amide nanocomposite coating material was reinforced with Fe2O3 nanoparticles. The nanocomposite coating was prepared on mild steel panels by curing with phenol formaldehyde at appropriate temperature for desirable time period. The incorporation of nanoparticles augmented the coating performance, thermal stability as well as corrosion resistance of coating in saline medium, due to higher stability of Fe2O3 nanoparticles under corrosive conditions. The coatings obtained were scratch resistant, impact resistant, flexibility retentive with safe usage upto 225 °C. The reaction path is simple and time-saving and the material is applicable in commercial coatings.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSP-2021/113), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia for the support.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Quantitative structure–activity relationship and molecular docking of 4-Alkoxy-Cinnamic analogues as anti-mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. King Saud Univ. – Sci.. 2020;32(1):67-74.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Corn oil based poly(urethane-ether-amide)/fumed silica nanocomposite coatings for anticorrosion application. Int. J. Polym. Anal. Charact.. 2019;24(6):533-547.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Corn oil based poly(ether amide urethane) coating material—Synthesis, characterization and coating properties. Ind. Crops Prod.. 2014;57:17-28.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Development of poly(urethane-ester)amide from corn oil and their anticorrosive studies. Int. J. Polym. Anal. Charact.. 2017;22(4):281-293.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Corn Oil-Derived Poly (Urethane-Glutaric-Esteramide)/Fumed Silica Nanocomposite Coatings for Anticorrosive Applications. J. Polym. Environ.. 2020;28(3):1010-1020.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mechanically Strong, Hydrophobic, Antimicrobial, and Corrosion Protective Polyesteramide Nanocomposite Coatings from Leucaena leucocephala Oil: A Sustainable Resource. ACS Omega. 2020;5(47):30383-30394.

- [Google Scholar]

- Formulation of silica-based corn oil transformed polyester acryl amide-phenol formaldehyde corrosion resistant coating material. J. Appl. Polym. Sci.. 2022;139(7):51651.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Rapeseed oil gallate-amide-urethane coating material: Synthesis and evaluation of coating properties. e-Polymers. 2022;22(1):190-202.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Efficiency of edible coating chitosan and cinnamic acid to prolong the shelf life of tomatoes. J. Trop. Resour. Sustain. Sci.. 2019;7(1):47-52.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antibacterial activity and mechanism of cinnamic acid and chlorogenic acid against Alicyclobacillus acidoterrestris vegetative cells in apple juice. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol.. 2019;54(5):1697-1705.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effect of nano-ZnO particles on the corrosion behavior of alkyd-based waterborne coatings. Prog. Org. Coat.. 2009;64(4):371-382.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- High performance anti-corrosive epoxy–titania hybrid nanocomposite coatings. New J. Chem.. 2017;41(11):4599-4610.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- High-Performance Soya Polyurethane Networked Silica Hybrid Nanocomposite Coatings. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res.. 2015;54(51):12770-12787.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- NiO nanofiller dispersed hybrid Soy epoxy anticorrosive coatings. Prog. Org. Coatings. 2019;133:61-76.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mechanically robust hydrophobic interpenetrating polymer network-based nanocomposite of hyperbranched polyurethane and polystyrene as an effective anticorrosive coating. New J. Chem.. 2020;44(15):5980-5994.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and characterization of phenol–formaldehyde microcapsules containing linseed oil and its use in epoxy for self-healing and anticorrosive coating. J. Appl. Polym. Sci.. 2011;119(5):2911-2916.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Nano iron oxide dispersed alkyd coating as an efficient anticorrosive coating for industrial structures. Prog. Org. Coat.. 2019;132:76-85.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial and antibiofilm effects of trans-cinnamic acid nanoemulsion and its potential application on lettuce. LWT. 2018;94:25-32.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Efficient and eco-friendly extraction of corn germ oil using aqueous ethanol solution assisted by steam explosion. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol.. 2016;53(4):2108-2116.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Physico-mechanical and electrochemical corrosion behavior of soy alkyd/Fe3O4 nanocomposite coatings. RSC Adv.. 2014;4(29):14936-14947.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bioenergy: a foundation to environmental sustainability in a changing global climate scenario. J. King Saud Univ. – Sci.. 2022;34(1)

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cinnamic Acid Derivatives and Their Biological Efficacy. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(16):5712-5742.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Xanthan gum based edible coating enriched with cinnamic acid prevents browning and extends the shelf-life of fresh-cut pears. LWT - Food Sci. Technol.. 2015;62(1):791-800.

- [Google Scholar]

- Recent advances in vegetable oils based environment friendly coatings: A review. Ind. Crops Prod.. 2015;76:215-229.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sustainable Hydrophobic and Moisture-Resistant Coating Derived from Downstream Corn Oil. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng.. 2019;7(9):8766-8774.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Recent advances in vegetable oil-based polymers and their composites. Prog. Polym. Sci.. 2017;71:91-143.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Structure-Dependent Inhibition of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia by Polyphenol and Its Impact on Cell Membrane. Front. Microbiol.. 2019;10:2646.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Electrochemical and anti-corrosion behaviors of water dispersible graphene/acrylic modified alkyd resin latex composites coated carbon steel. J. Appl. Polym. Sci.. 2017;134(11)

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Appendix A

Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2022.102365.

Appendix A

Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article: