Translate this page into:

Comparative studies of thermophysical and physicochemical properties of shea butter prepared from cold press and solvent extraction methods

⁎Corresponding author. mabdul-hammed@lautech.edu.ng (Misbaudeen Abdul-Hammed)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Shea nuts are good sources of nutritional proteins and fats. Shea butter from Soxhlet extraction method has higher unsaturated fats than that from cold press method. Higher thermal stability was displayed by the shea butter from cold press methods as measured from activation energies calculation.

Abstract

Over the years, the importance of shea butter, for its exceptional use in food and cosmetics industries, has been over-emphasized. This work compares the qualities of shea butter produced from two methods of extraction with respect to thermal stability and physicochemical properties. Two different extractions; Soxhlet extraction (SBSE) and cold press (SBCP) methods were carried out, and proximate analysis, viscosity, specific gravity and refractive index of the butter were equally analyzed. The activation energies (Ea) were determined from Arrhenius-type plots, and the enthalpy, entropy as well as Gibb’s free energy were obtained from Eyring plots. Proximate analysis showed that the nuts contains 5.30% moisture, 16.45% crude protein, 4.51% ash, 46.50% crude fats, 4.45% crude fibre and 23.24% carbohydrate. Peroxide values of 4.00 and 6.50 Meq/kg, acid values of 3.50 and 9.54 mg KOH/g, iodine values of 53.82 and 54.93 g/100 g and saponification values of 172.2 and 185.7 mg/KOH were obtained for the shea butter from Soxhlet extraction (SBSE) and cold press (SBCP) methods, respectively. SBSE contains higher level of unsaturated fatty acid, oleic and linoleic acids, than SBCP, while the trend was reversed in relation to the saturated fatty acid contents. The viscosity, specific gravity and refractive index of both SBCP and SBSE are within the same range. The viscosities of the butters decrease with temperature and the activation energies (Ea) determined from Arrhenius-type plots are 170.19 and 190.97 J/mol for SBSE and SBCP, respectively, as a measure of their thermal stability. The enthalpy, entropy and Gibb’s free energy of activation obtained from Eyring plots are approximately the same for the butters from the two extraction methods and have the values of approximately 2900 J mol−1, −165 J mol−1 K−1 and 52.10 kJ mol−1, respectively, showing that the processes involved are endothermic and of non-spontaneous nature. The butter extracts exhibit good thermophysical and chemical properties and could be used as valuable industrial raw materials.

Keywords

Shea butter

Proximate analysis

Arrhenius plot

Eyring plot

Viscosity

Activationenergy

Thermodynamics

1 Introduction

There is an increasing trend of the worldwide demand for oils and fats from vegetable origins in food and cosmetics industries, as they are excellent sources of antioxidants and dietary energy as well as good raw materials for industrial products including biofuels (Ramadan et al., 2015). One of these highly demanding fat is shea butter which is obtained from shea tree (Vitellaria paradoxa, C.F. Gaertn), an indigenous wild tree popularly grown in the parklands of African Savannah (Hall et al., 1996).

Shea nut is known as Kandayi, Osisi and Èmí among the Hausa, Igbo and Yoruba people of Nigeria, respectively. It is obtained from the fruits of shea tree, which is made up of a green epicarp, a fleshy pulp and a relatively hard shell enclosing the shea kernel (Olaniyan and Oke, 2007b). Shea butter has been used as far back as ancient Egypt, as a local healer for rheumatism, inflammation of nostrils, nasal congestion, leprosy and minor bone dislocation (Israel, 2014; Olaniyan and Oke, 2007b; Goreja, 2005; Badifu, 1989; Tella, 1979). It is used for body massaging, as insects repellant, for protecting the sensitive skin of the new born baby from irritants and in accelerating healing after circumcision as well as for the protection of body against stimulus infection (Goreja, 2005; Israel, 2014). Shea butter is also used in local cooking and as a raw material in cosmetic and pharmaceutical products as well as a substitute for cocoa butter in confectioneries and chocolate industries (Maranz et al., 2004). Studies on the physical properties of shea butter revealed a high oil content ranging from 17.4 to 59.1% respectively (Honfo et al., 2014; Okullo et al., 2010).

The technology used for extracting shea butter is mostly the traditional boiling (cold press) method involving roasting, pressing of the nuts, churning the extracted liquid with water followed by boiling, sieving and finally cooling. Other methods of shea butter production include mechanical pressing and solvent extraction which are used industrially (Olaniyan and Oje, 2007a; Abdul-Mumeen et al., 2013). Solvent extraction method is done using n-hexane (Ikya et al., 2013) and this process has been optimized recently (Ajala et al., 2016). However, there is a need to compare the physicochemical and thermophysical properties as well as the fatty acid profiles of the shea butter produced using the cold press and solvent extraction methods, in order to ascertain whether the shea butter from the two methods are comparably the same or not. This work investigates the proximate composition of shea nut before extraction, and compares the physico-chemical properties, fatty acid profile and thermophysical properties of the shea butter obtained by cold press and Soxhlet extraction processes.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Sample preparation

Fresh shea (Vitellaria paradoxa) nuts were collected from Banni village of Kaiama Local Government Area of Kwara State, Nigeria. Samples were de-pulped manually to separate the nut from pulp, washed with water and sundried for 3 weeks. About 500 g of the sample (shea kernel) were ground, packed in a low density polythene bag and stored in a refrigerator for further analysis.

2.2 Determination of proximate composition

Proximate analysis was carried out using a previously reported method (AOAC, 2010). The moisture content was determined by drying 2 g of the sample in an oven (MINO/75/SS/F, Genlab, UK) at 110 °C for 3 h until constant weight was obtained. The ash content was determined from 2 g of the sample placed in a muffle furnace which is maintained at 550 °C for 5 h, while crude fibre content was estimated by consecutive acid and alkali digestion followed by washing, drying, ashing at 600 °C. Crude fat was obtained by exhaustively extracting about 30 g of the sample in a Soxhlet apparatus using n-hexane solvent. Crude protein (% total Nitrogen × 6.25) was determined by Kjeldah method. The carbohydrate content was determined by difference.

2.3 Production of the shea butter from cold press and solvent extraction methods

Shea butter from cold press (traditional) method, SBCP, was obtained by roasting and manually pounding the nuts into a paste. The lipid fraction (shea butter) was removed by manually mixing and squeezing the oil from the kernel paste with alternate admixture of warm and cold water. The kernel fragments and other impurities, which settle to the bottom of the dried liquid, were coagulated, by boiling out residual moisture. The liquid shea butter was then poured through a filter cloth and left to cool and solidify. The production of shea butter from the solvent extraction procedure, SBSE, was carried out in a 500 ml Soxhlet extractor using n-hexane as the solvent (Ajala et al., 2016).

2.4 Chemical and physical analysis of crude fats

2.4.1 Chemical analysis

Determinations of peroxide, iodine, saponification and acid values for the two methods of extraction were carried out using AOAC (2010) methods.

2.4.2 Fatty acid analysis and quantification

Fatty acid analysis was carried out as described previously (Joslyn, 1970) with modifications and methylation of the ether extract of the oil was done using AOAC (2010) procedure. 100 mg of the extracted fat was weighed, 1 ml of 0.5 M KOH in methanol and 1 ml boron trifloride in methanol were added separately. The tube was shaken in a vortex mixer and transferred to a COD reactor for 1 h at 100 °C. The tubes were then allowed to cool and 2 ml of 10% NaCl and 2 ml of hexane were added, the mixture was shaken vigorously and left to settle for the separation of phases subsequently. An aliquot of 1 ml was taken from the supernatant, deposited in a hermetically sealed amber vial with 9 ml of hexane and frozen at 26 °C until injection into the GC (Model 7693, Agilent Technologies, USA, with auto sampler) equipped with flame ionization detector (FID). HP5 capillary column (30 m long by 0.25 mm, internal diameter and 0.25 µm phase thickness) was used. The temperature of the injection and detector was 26–27 °C respectively. The flow rate of the carrier gas (N2) was 2 ml/min, oven temperature programming was as follows: 100 °C (initial) to 180 °C (5 °C/min) and finally increasing to 220 °C (0.8 °C/min). Injection volume was 0.5 µl of each sample; fatty acid methyl ester (FAME) peaks were identified by comparison of retention times to the standard mixture (GLC-10, GLC-20, GLC-40) and GLC-80 sepms (Manufactured by St Louis, MO, USA). The peak areas were computed and the percentage of FAME was obtained as area percentages by direct normalization data and is expressed as normalized peak area percent.

2.4.3 Specific gravity and refractive index measurement

A clean and dry density bottle was used to determine the specific gravity of the butter after been melted. The empty density bottle was weighed then filled with oil, and water. The value for the weighed density bottle when filled with oil and when filled with water was then compared with that of empty density bottle and the specific gravity was then calculated. A refractometer was used to determine the refractive index at 35 °C.

2.4.4 Viscosity measurements

A rheometer method previously described (Nzikou et al., 2009) was used to measure the viscosities of the butter when heated. By this procedure a concentric cylinder system was submerged in the oil and the force necessary to overcome the resistance of the viscosity to the rotation is measured. The viscosity value, in mPa.s is automatically calculated on the basis of the speed and the geometry of the probe. The temperatures (30–75 °C) were controlled with water bath connected to the rheometer. The experiments were carried out by placing 3 ml of the sample in a concentric cylinder system using a shear rate of 100 s−1.

2.5 Viscosity-temperature dependency

The relationship between the viscosity and temperature has been shown in an Arrhenius-type equation previously (Singh and Heldman, 2001) and this is expressed in Eqs. (1) and (2) as follows:

This equation can further be re-written in the form shown in Eq. (2) below:

However, the enthalpy, entropy and Gibbs free energy of activation are calculated from Eyring-type equation, similar to Arrhenius-type equation but based on transition state theory, given as follows:

This can also be rewritten as:

The enthalpy and entropy of activation could be obtained from the slope and intercept of the plot of against respectively, while the Gibb’s free energy of activation () could be obtained from the Eq. (5) below:

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Proximate composition of the shea nut

The proximate composition of the shea nut was reported in Table 1. The moisture content of the nut was 5.30%. This is closer to that of Jatropha curcas seed (5.12%) (Nzikou et al., 2009), but lower than that reported for Moringa oleifera seed (8.30%) (Anwar and Rashid, 2007). This low moisture content could enhance the nut shelf life and prevents microbial infection. The ash content of the shea nuts was 4.51% dry matter (DM) in the same range with that of Sesamum indicum L. (4.20%) (Nzikou et al., 2009). Lower ash content is desirable because of its effect on biomass energy value, although it is also used as a measure of the mineral contents of the original food materials. The protein content was 15.45% which is lower than 20% and 25% reported earlier for Sesamum indicum L. and Jatropha currcas, respectively (Nzikou et al., 2009). Crude fat (45.50%) was the highest component present in the shea nut under study with its value in agreement with a previous report stating the crude fat of various shea nuts ranging from 41.00 to 53.56% (Okullo et al., 2010). The value is slightly lower than that in Jatropha curcas (48.50%) (Nzikou et al., 2009). The crude fibre for the shea nut was 7.50% which is lower than the reported value in Jatropha curcas (9.40%), but higher than the reported values in most of the domesticated nuts such as groundnut (3.50%), soya beans (5.30%), cashew (3.20%) and melon (2.20%). The major constituents of crude fibre are cellulose and little lignin, with lignin being indigestible in humans (Dhingra et al., 2011).

Parameters

Composition (%)

Moisture content

5.30 ± 0.15

Ash content

4.57 ± 0.11

Crude proteins

15.45 ± 0.40

Crude fat

45.50 ± 2.37

Crude fibre

7.50 ± 0.22

Carbohydrate

22.50 ± 1.96

3.2 Chemical properties of the shea butter from the two methods

The % oil yield of the shea butter obtained from Soxhlet extraction (SBSE) and cold press methods (SBCP) are 44.65% and 33.34%, respectively (Table 2) showing that shea butter obtained from solvent extraction has higher yield, but costlier as it involved the use of expensive chemical reagents, which may not be easily accessible for small scale production. The values for the oil yield are similar to what have been observed earlier (Ikya et al., 2013).

Chemical Properties

Butter type

SBSE

SBCP

% Oil Yield

44.65 ± 0.99

33.34 ± 1.12

Peroxide Value (Meq/kg)

4.00 ± 0.18

6.50 ± 0.53

Acid value (Mg KOH/ g)

3.50 ± 0.02

9.54 ± 0.40

Free fatty acid (%)

1.62 ± 0.12

4.80 ± 0.02

Iodine value (g/100 g)

53.76 ± 0.53

54.93 ± 0.14

Saponification value (mg/g KOH)

172.20 ± 1.40

185.70 ± 1.0.35

Physical Properties

Refractive index

1.465 ± 0.002

1.466 ± 0.004

Specific gravity

0.901 ± 0.004

0.911 ± 0.003

Viscosity (mPa.s)

46.98 ± 1.22

47.02 ± 2.35

Peroxide values of 4.00 and 6.50 Meq/kg were obtained for the butter from shea nuts obtained by Soxhlet extraction (SBSE) and cold press methods (SBCP), respectively (Table 2). The peroxide value is used in assessing the extent of oil spoilage. The obtained values indicate that the shea butter in both methods were recently prepared, since the value were less than 10 Meq/kg compared to the range of between 30 and 40 Meq/kg for rancid oils and fats as the detection of higher peroxide value usually give the initial evidence of oil rancidity in an unsaturated fat and oils. It also gives a measure of the extent to which an oil sample has undergone primary oxidation. The obtained value (6.50) for SBCP suggested that butter obtained from cold press method contains no detectable level of vitamin E (a powerful antioxidant) and has higher value of peroxides (5.00–8.30 Meq/kg), this supports the fact that cold press method of extraction of shea butter is susceptible to oxidation (Dermiş et al., 2012) when compare to Soxhlet extraction method, although both are edible since the peroxide values are less than 10 Meq/kg in both materials.

The acid value of the shea butter obtained from the nuts of Vitellaria paradoxa were 3.50 and 9.50 (mg KOH/g) for SBSE and SBCP, respectively (Table 2). Acid values express the quantity of free fatty acid present in the oils and its value is often used as a general indication of the condition and usability of the oil. The reported acid values of shea butter varied from 0.1 to 21.2 mg KOH/g (Nkouam et al., 2007) with an average of 8.1 mg KOH/g. The butters obtained for SBSE satisfied the requirement for soap, food and industrial application as the required acid values for butter that is to be used for cosmetics and food industries are in the range of 0.3–9.0 mg KOH/g of oil respectively (Ghadge and Raheman, 2005). However, the acid value obtained for SBCP was slightly higher than the required average, although, such slight difference may have little or no effect on its usage for that purpose.

Iodine value is a measure of the degree of unsaturation of oils and expresses the susceptibility of the oil to oxidation and the extent of its contamination (Zuleta et al., 2012). The iodine values for SBSE and SBCP, 53.31 and 54.95 g/100 g, respectively (Table 2), compare well with average iodine values of 51.4 g/100 g for non-drying oils (Honfo et al., 2014). The relatively closed values obtained for both methods were slightly higher than the average values reported, which could be traced to genetic substitution as well as environmental factors (Sonau et al., 2006). These shea butters could be useful for soap production because of its low degree of unsaturation and non-drying oil properties, but are not applicable for the production of paint where drying oils, such as linseed oil, of higher iodine values are desired.

The saponification values of 172.2 and 185.7 mg KOH/g were obtained for SBSE and SBCP, respectively. Shea butter extracted via cold press method (SBCP) contained a higher molecular weight fatty acid when compared with SBSE. However, these values from both methods were in close range when compared with those of palm oil (190–209 mg KOH/g), olive oil (190–192 mg KOH/g), soya beans (185–195 mg KOH/g) and cotton seed oil (184–198 mg KOH/g) which are commonly used for soap making (Anhwange et al., 2004; Adepoju et al., 2013). Saponification value is an indication of average molecular weight of the fatty acid in an acylglycerol (Akhtar et al., 2009).

3.3 Fatty acid profiles of the shea butter from the two methods

The Fatty acid compositions of the fat extracted from Vitellaria paradoxa are depicted in Table 3. The major saturated fatty acids for SBCP and SBSE were stearic acid (49.47 and 40.09%) and palmitic acid (6.5 and 4.87%), respectively. The main unsaturated fatty acids were oleic (37.61 and 47.81%) and linoleic (2.10 and 2.19%) for SBCP and SBSE, respectively. Slightly higher total saturated fatty acids (56.04%) accounted for in the shea butter obtained from the traditional method (SBCP) may be responsible for its slightly higher viscosity compared to the shea butter from the Soxhlet extraction method (SBSE) with a total saturated fatty acid of 44.90%. Meanwhile, lowering the consumption of saturated fats, minimizing or eliminating trans-fat and increasing the polyunsaturated and monounsaturated fatty acid consumptionhave been recommended, in order to improve the integrity of cardiovascular system (Siri-Tarino et al., 2010). Higher polyunsaturated and monounsaturated fatty acids could rather be obtained from other vegetable sources such as sunflower, soya beans and olives. The minor components observed may be a group of other compounds which are known to provide stability to oils and fats against oxidation.

Fatty acids content (%)

SBSE

SBCP

Palmitic acid (C16:0)

4.87 ± 0.02

6.57 ± 0.05

Stearic acid (C18:0)

40.09 ± 0.19

49.47 ± 0.60

Total Saturated

44.96 ± 0.20

56.04 ± 0.62

Oleic acid (C18.1)

47.81 ± 0.08

37.61 ± 0.14

Linoleic acid (C18.2)

2.91 ± 0.02

2.10 ± 0.02

Total unsaturated

50.72 ± 0.08

39.71 ± 0.14

Other compounds/Minor Components

4.32 ± 0.19

4.25 ± 0.47

3.4 Physical properties of the butter

Apart from using the chemical properties to describe the quality of oils and fats, physical properties, such as refractive index, specific gravity and viscosity, among others, are of paramount importance and the values obtained for the shea butter are reported in Table 2. The refractive index values of 1.465 and 1.466 were obtained for SBSE and SBCP, respectively. The refractive index is the ratio of the speed of light in a vacuum to that of the oil under examination. It can be related to the degree of unsaturation, and therefore used for sorting fats and oils that are suspected to be adulterated (Olaniyan and Oke, 2007b). The values obtained fall within the physical range of a typical refractive index for shea butter, 1.463–1.467 (Okullo et al., 2010). The specific gravity of shea butter for cold press method (SBCP) was 0.911 while that from Soxhlet extraction method (SBSE) was 0.900. This reflects that molecules of the shea butter from the traditional method are slightly more closely packed than those from Soxhlet extraction method, probably as a result of the mechanical press involved in the former.

Viscosity is a measure of resistance of fluid to deform under shear stress. It is commonly perceived as the thickness or resistance to pouring as it describes the fluid internal resistance to flow and may be thought of as a measure of fluid friction (Geller and Goodrum, 2000; Akhtar et al., 2009). The larger the molecular size of triglycerides (especially the one with saturated fatty acids) present in vegetable oils, the higher the viscosity, the higher the density and the lower the volatility, although these may not be the same in the case of diesel (Selim, 2009). At room temperature, the viscosities of SBCP and SBSE are 47.02 and 46.98 mPa.s, respectively (Table 2), and are quite similar in values. The viscosities of shea butters obtained here are higher than that observed for walnut oil (42.9 mPa.s) but lower than that of rice ban oil (59.3 mPa.s), respectively at room temperature (Diamante and Lan, 2014) This could be attributed to higher saturated fatty acid contents of the shea butters (44.96% for SBSE and 56.04% for SBCP, Table 3) observed in this work compared to 22.3% and 9.0% in the rice ban and walnut oils, respectively (Diamante and Lan, 2014).

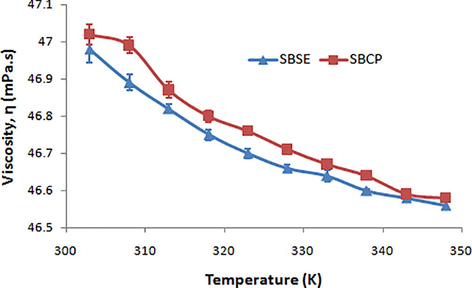

3.5 Activation energy as a measure of the thermal stability of the butter

In order to determine the rheological properties of the shea butters (SBSE and SBCP), the influence of temperature on their viscosities was studied. As the temperature increases, the viscosities of the butters decrease exponentially (Fig. 1), thus confirming previous assertions (Fasina and Colley, 2008). There is no significant difference between the viscosities (or with the trend of viscosities changes with temperature) in the two shea butters, either from Soxhlet extraction or from cold press methods.

The viscosities of the shea butters from Soxhlet extraction (SBSE) and cold press (SBCP) methods decrease exponentially with increasing temperature.

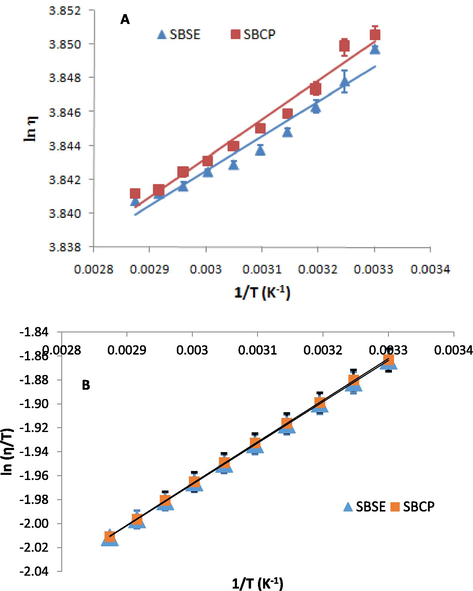

In an attempt to examine the thermal stability of the shea butters, the activation energy of the process was calculated from the Arrhenius-type equation (Equation (2)). The slopes, coefficients of determination and the activation energies obtained from the plot of against (Fig. 2A) for the shea butters from Soxhlet extraction (SBSE) and cold press (SBCP) methods are summarized in Table 4. From Table 4, the activation energies of SBCP and SBSE are 190.97 and 170.19 kJ mol−1 with determination coefficients (R2 values) of 0.9711 and 0.9579, respectively. The higher the activation energy, the greater the energy needed to effect a viscosity change and, hence, the greater the stability of the oil. A significant difference of about 20% exists between the activation energies of the shea butters and this is significant enough to conclude that the shea butter from the cold press method tend to be slightly more stable than that from Soxhlet extraction method. It has been shown previously that the processes involved in rapeseed oil extraction affected the rheological properties of the oil (Liu et al., 2012) and the higher the unsaturation degree in chemical chain of an oil, the lower its stability and hence the lower the activation energy (Litwinienko et al., 2000). Therefore the slightly lower activation energy in the shea butter from Soxhlet extraction might be attributed to its higher content of unsaturated fatty acids than the one obtained from cold press method.

(A) Arrhenius-like; (B) Eyring-like plots for the viscosity-temperature changes in the shea butters from Soxhlet extraction (SBSE) and cold press (SBCP) methods.

Parameters from Arrhenius-type plot

Activation energy, Ea (kJ mol−1)

Viscosity Pre-exponential factor, (mPa.s)

Coefficients of determination (R2)

SBCP

190.97

43.55

0.971

SBSE

170.19

43.86

0.957

Parameters from Eyring-type plot

Enthalpy of Activation, (J mol−1)

Entropy of Activation, (J mol−1 K−1)

Gibb’s free energy of Activation, at 298 K (kJ mol−1)

Coefficients of determination (R2)

SBCP

2868

−165

52.1

1.000

SBSE

2889

−165

52.1

0.9999

However, it could be concluded that shea butters obtained in this study is far more stable than many vegetable oils, as the activation energy values obtained for shea butter oil are much higher when compared with those of peanut (21 kJ mol−1) and safflower (30 kJ mol−1) oils, respectively (Diamante and Lan, 2014). Oils with high activation energy (Ea) are desirable in biodiesel production as various researchers have reported different values for biodiesel from different sources. The activation energy of biodiesel from jatropha which contained pyrogallol was 103.96 kJ mol−1 (Chen et al., 2011), 97.02 kJ mol−1 was obtained for biodiesel from safflower with propyl gallate (Xin et al., 2009), 72.01 kJ mol−1 for the biodiesel from ternary mixture of soybean oil, beef tallow and poultry fat (Galvan et al., 2013), and 85.68 kJ mol−1 for biodiesel obtained from free fatty acids (FFAs) with antioxidant Ethanox 4760E (Chen and Luo, 2011). Also 65.08 and 36.11 kJ mol−1 have been obtained for soybean biodiesel, with and without antioxidant, respectively (Borsato et al., 2012). The high activation energy from the shea butter might have been responsible for its use in biodiesel production (Ajala et al., 2016).

3.6 Comparison between the enthalpies, entropies and Gibb’s free energies of the butter from the two methods

The thermodynamic parameters during the process of viscosity changes with increasing temperature could be calculated from Eyring-type equation, derived from activation complex theory, as shown in Eq. (3). A plot of against (Fig. 2B) gives a slope and an intercept, from which the enthalpy () and entropy of activation, could be calculated, respectively (Table 4).

As shown in Table 4, the thermodynamic activation parameters, enthalpy and entropy of activation, evaluated based on activation complex theory (ACT), are closed at about 2900 J mol−1 and −165.20 J mol−1, for both cold press and Soxhlet extraction methods. The Gibb’s free energy of activation (), determined at room temperature by the thermodynamic fundamental Eq. (5), was estimated to be 52.1 kJ mol−1.

The positive values of indicates that the process is endothermic while the negative values of indicate that entropy decreases on forming the transition state, which often indicates an associative mechanism in which the combining molecules form a single activated complex (Espenson, 2002). However, the positive showed the non-spontaneity of the two processes.

4 Conclusion

This study shows that Vitellaria paradoxa nuts contain high level of crude fat, proteins and carbohydrates which make it a valuable ingredient with high nutritional and health benefits. The physico-chemical characteristics and fatty acid profiles exhibited qualify the butter as potential raw materials for cosmetics, soap and food processing industries. The high activation energy, as a result of high saturated fatty acids in the shea butter, might make it valuable in the biodiesel production, while the thermodynamic activation parameters show that the temperature related changes in viscosity process is endothermic and non-spontaneous and the molecules in shea butter undergo associative mechanism based on activation complex theory. However, the trend observed from the physico-chemical parameters of the butter showed that butter extracted via cold press method exhibit higher acid value, saponification value and viscosity when compared with that from solvent extraction method whereas higher iodine value in the latter may subject it to oxidative instability. The specific gravity reveals that the molecules in cold pressed shea butter are more closely packed than those of the Soxhlet method. The lower activation energy (Ea) obtained from fitting the parameters from Soxhlet method could result from its higher unsaturated fatty acid profile.

Acknowledgements

The authors are greatly indebted to the Abdus Salam International Centre for Theoretical Physics (ICTP), Italy for the award of Junior Associateship to Dr. Abdul-Hammed, M. and for the use of the institutional facilities which aid the preparation of this manuscript.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Biochemical and microbiological analysis of shea nut cake: a waste product from shea butter processing. J. Agric. Biotechnol. Sustain. Dev.. 2013;5(4):61-68.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparative studies of the chemical parameters of the oil extracted from the seed of ripe and unripe fruits of Blighia sapida (ackee) J. Chem. Pharm. Res.. 2013;5(10):386-390.

- [Google Scholar]

- Optimization of solvent extraction of shea butter (Vitellaria paradoxa) using response surface methodology and its characterization. J. Food Sci. Technol.. 2016;53(1):730-738.

- [Google Scholar]

- Rheological studies and characteristics of different oils. J. Chem. Soc. Pak.. 2009;31(2):201-206.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chemical Studies of the Seeds of Moringa oleifera (Lam) and Detarium microcarpum (Guill and Sperr) J. Biol. Sci.. 2004;4(6):711-715.

- [Google Scholar]

- Physico-chemical characteristics of Moringa oleifera seeds and seed oil from a wild provenance of Pakistan. Pak. J. Bot.. 2007;39(5):1443.

- [Google Scholar]

- AOAC, 2010. Association of Official Analytical Chemists. Official Methods of Analysis, 18th ed. Washington D.C., USA.

- Lipid composition of Nigerian Butyrospermum paradoxum kernel. J. Food Compos. Anal.. 1989;2(3):238-244.

- [Google Scholar]

- Kinetics of oxidation of biodiesel from soybean oil mixed with TBHQ: determination of storage time. New Chem.. 2012;35:733-737.

- [Google Scholar]

- Property modification of jatropha oil biodiesel by blending with other biodiesels or adding antioxidants. Energy. 2011;36:4415-4421.

- [Google Scholar]

- Oxidation stability of biodiesel derived from free fatty acids associated with kinetics of antioxidants. Fuel Process. Technol.. 2011;92:1387-1393.

- [Google Scholar]

- Determination of peroxide values of some fixed oils by using the mFOX method. Spectrosc. Lett.. 2012;45(5):359-363.

- [Google Scholar]

- Absolute viscosities of vegetable oils at different temperatures and shear rate range of 64.5 to 4835 s−1. J. Food Process.. 2014;2014:6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chemical Kinetics and Reaction Mechanisms (second ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Education; 2002. p. :296.

- Viscosity and specific heat of vegetable oils as a function of temperature: 35 °C to 180 °C. Int. J. Food Prop.. 2008;11(4):738-746.

- [Google Scholar]

- Determination of the kinetics and thermodynamics parameters of biodiesel oxidation reaction obtained from an optimized mixture of vegetable oil and animal fat. Energy Fuels. 2013;27(11):6866-6871.

- [Google Scholar]

- Rheology of vegetable oil analogs and triglycerides. J. Am. Oil. Chem. Soc.. 2000;77(2):111-114.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biodiesel production from mahua (Madhuca indica) oil having high free fatty acids. Biomass Bioenergy. 2005;28(6):601-605.

- [Google Scholar]

- Shea Butter: The Nourishing Properties of Africa’s Best-Kept Natural Beauty. New York: Amazing Herbs Press; 2005. p. :53.

- Vitellaria paradoxa: A Monograph. Bangor U.K.: School of Agricultural and Forest Sciences, University of Wales; 1996. p. :105.

- Nutritional composition of shea products and chemical properties of shea butter: a review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr.. 2014;54(5):673-686.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of extraction methods on the yield and quality characteristics of oils from shea nut. J. Food Resour. Sci.. 2013;2:1-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of oral and topical use of the oil from the nut of Vitellaria paradoxa. J. Nutr. Food Sci.. 2014;4:32.

- [Google Scholar]

- Methods in Food Analysis: Physical, Chemical, and Instrumental Methods of Analysis (second edition). New York: Academic Press; 1970. p. :845.

- Study on autoxidation kinetics of fats by differential scanning calorimetry. 1. Saturated C12–C18 fatty acids and their esters. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res.. 2000;39(1):7-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Influence of extraction processing on rheological properties of rapeseed oils. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc.. 2012;89(1):73-78.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nutritional values and indigenous preferences for Shea fruits (Vitellaria paradoxa C.F. Gaertn. F.) in African agroforestry parklands. Econ. Bot.. 2004;58:588-600.

- [Google Scholar]

- Oil extraction from Shea Kernel (Vitellaria paradoxa Gaertn) and Canarium pulp (Canarium schweinfurthi, Engl.) using supercritical CO2 and hexane. A comparative study. Res. J. Appl. Sci.. 2007;2:646-652.

- [Google Scholar]

- Characterization of Moringa oleifera seed oil variety in Congo-Brazzaville. J. Food Technol.. 2009;7:59-65.

- [Google Scholar]

- Physico-chemical characteristics of shea butter (Vitellaria paradoxa C.F. Gaertn.) oil from the Shea district of Uganda. Afr. J. Food Agric. Nutr. Dev.. 2010;10(1):2070-2084.

- [Google Scholar]

- Development of mechanical expression rig for dry extraction of shea butter from shea kernel. J. Food Sci. Technol.. 2007;44:465-470.

- [Google Scholar]

- Quality characteristics of shea butter recovered from shea kernel through dry extraction process. J. Food Technol.. 2007;44:404-407.

- [Google Scholar]

- Functional characteristics, nutritional value and industrial applications of Madhuca longifolia seeds: an overview. J. Food Sci. Technol.. 2015;53(5):2149-2157.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reducing the viscosity of jojoba methyl ester diesel fuel and effects on diesel engine performance and roughness. Energy Convers. Manage.. 2009;50(7):1781-1788.

- [Google Scholar]

- Introduction to Food Engineering. London: Academic Press; 2001. p. :153-154.

- Saturated fat, carbohydrate, and cardiovascular disease. Am. J. Clin. Nutr.. 2010;91(3):502-509.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phenotypic variation of agromorphological traits of the shea tree, Vitellaria paradoxa C.F. Gaertn, in Mali. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol.. 2006;53:145-161.

- [Google Scholar]

- Preliminary studies on nasal decongestant activity from the seed of the shea butter tree. Butyrospermumparkii. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol.. 1979;7(5):495-497.

- [Google Scholar]

- Kinetics on the oxidation of biodiesel stabilized with antioxidant. Fuel. 2009;88:282-286.

- [Google Scholar]

- The oxidative stability of biodiesel and its impact on the deterioration of metallic and polymeric materials: a review. J. Braz. Chem. Soc.. 2012;23(12):2159-2175.

- [Google Scholar]