Translate this page into:

Activities of antioxidant enzymes in three species of Ludwigia weeds on feeding by Altica cyanea

⁎Corresponding author. anandamaybarik@yahoo.co.in (A. Barik)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Objectives

Altica cyanea (Weber) (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) is a potential biocontrol agent of rice-field weeds, Ludwigia adscendens (L.) Hara, L. parviflora Roxb., and L. octovalvis (Jacq.) Raven (Onagraceae) in India. Damage on leaf tissue causes stress on plants. Hence, this study aims to observe how the three Ludwigia species are trying to cope with the stress caused by feeding of A. cyanea adults at different time intervals.

Materials

Uninfested L. adscendens, L. parviflora, and L. octovalvis, and each Ludwigia species on which 5 adult A. cyanea females had fed on continuously for 6 h or 48 h were used for collection of leaf tissues. The amounts of total ROS, H2O2, activity of enzymatic antioxidants [superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), glutathione S-transferase (GST), activity of peroxidases towards phenolic substances {guaiacol peroxidase (GPX) and pyrogallol peroxidase (PPX)}, and ascorbate peroxidase (APOX)] and non-enzymatic antioxidants (phenolics and thiols) were estimated from leaf tissues of undamaged and insect damaged Ludwigia species using standard protocols.

Results

The amounts of total ROS and H2O2 were higher in each Ludwigia species after 48 h feeding by A. cyanea followed by plants after 6 h feeding by A. cyanea and undamaged plants. The activities of antioxidant enzymes such as CAT, SOD, GST, APOX, PPX, and GPX were higher in each Ludwigia species after 48 h feeding by A. cyanea compared to undamaged plants. Total proteins and thiols were higher in each undamaged Ludwigia species compared to insect damaged plants; whereas total phenols were higher in each insect damaged Ludwigia species compared to undamaged plants.

Conclusions

Higher amounts of total ROS and H2O2 in each insect damaged Ludwigia species compared to undamaged plants suggested that A. cyanea feeding resulted stress in the insect damaged plants. Higher amounts of CAT, SOD, GST, and APOX in insect damaged Ludwigia species compared to undamaged plants suggested that these four enzymes were acting as antioxidants to reduce the stress created in plants due to insect herbivory.

Keywords

Ludwigia adscendens

L. parviflora

L. octovalvis

Total ROS

H2O2

Enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidants

1 Introduction

Weeds exert a direct negative effect on rice production by competing for resources with rice in rice-fields. Ludwigia is a pantropical genus represented by 82 species, is the only member of Ludwigioideae of the family Onagraceae (Wagner et al., 2007), and is native to South America (Hernández and Walsh, 2014). Seven species and one infraspecific taxon of Ludwigia are available in India (Barua, 2010). In West Bengal, Ludwigia adscendens (L.) Hara, L. parviflora Roxb., and L. octovalvis (Jacq.) Raven are abundant in rice-fields. Rice-growers apply herbicides (bensulfuron, butachlor, fenoprop, imidazolinone, propanil, MCPA, 2,4-D, quinclorac, and thiobencarb) to control these weeds in rice-fields (Chin et al., 2007).

Altica cyanea Weber (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) consumes L. adscendens and L. octovalvis, while A. litigata Fall feeds on L. hexapetala (Maulik, 1936; Nayek and Banerjee, 1987; Mitra et al., 2017a,b). The insect, A. cyanea has been recorded in rice-fields of tropical and subtropical regions where Ludwigia species are available, and the insect is harmless on rice (Nayek and Banerjee, 1987; Xiao-Shui, 1990; Azad et al., 2015). Three instars of A. cyanea voraciously consume leaves and stems of L. adscendens for 3 weeks, while adults feed on L. adscendens for 7–8 weeks (Nayek and Banerjee, 1987; Xiao-Shui, 1990). The insect has also been recorded from Bangladesh, Thailand, Vietnam, Pakistan, China, Japan, and Malaysia (Maulik, 1936; Nayek and Banerjee, 1987; Xiao-Shui, 1990; Azad et al., 2015).

An inherent property of living organism is to defense against stress. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are generated in plants to cope with the stress caused by abiotic (temperature and light) and biotic (pathogen attack and herbivore feeding) factors. Superoxide and hydrogen peroxide are important ROS, which are stored in plants following abiotic and biotic stresses. ROS production may lead to oxidation burst, and plants employ a network of signal transduction pathways through complex mechanisms to scavenge ROS (Bhattacharjee, 2012; Llorent-Martínez et al., 2017; Picot et al., 2017; Zengin et al., 2017). Enzymatic antioxidants: superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), glutathione S-transferase (GST), activity of peroxidases towards phenolic substances [guaiacol peroxidase (GPX) and pyrogallol peroxidase (PPX)], and ascorbate peroxidase (APOX), while non-enzymatic antioxidants such as phenolics and thiols are involved in scavenging or destroying ROS (Bi and Felton, 1995; Liu et al., 2010; Bhattacharjee, 2012).

Therefore in the current study, we have compared the activities of antioxidant enzymes such as SOD, CAT, GST, peroxidases towards phenolic substances (GPX and PPX), APOX, and non-enzymatic antioxidants (phenols and thiols) from three Ludwigia species (L. adscendens, L. parviflora, and L. octovalvis) fed by the adults of A. cyanea against undamaged plants to comment on how enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidants are involved in scavenging or destroying ROS in the three Ludwigia species.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Insect

Altica cyanea adults were collected by light trap from Ammannia baccifera L. (Lythraceae) and Trapa natans L. (Lythraceae) growing in the Crop Research Farm (CRF), The University of Burdwan, (23°16′ N, 87°54′ E), West Bengal, India. The insects were reared on T. natans in an environmental chamber at 27 ± 1 °C, 65 ± 10% relative humidity and photoperiod 12 l: 12 D. F2 females (between 1 and 2-wk-old) were used for feeding experiments and 12 h prior to feeding experiments, the insects were not provided food but with water.

2.2 Plants

Uninfested L. adscendens, L. parviflora, and L. octovalvis (ca. 6 cm height) plants were collected from the CRF, University of Burdwan, and each plant was separately put in a 12 cm diameter earthen pot containing ca. 1500 cm3 of soil. Plants were kept in natural condition during March–April 2018 (25–30 °C). To prevent insect attacks and unintentional infections, fine mesh nylon net [50 cm (height) × 30 cm (diameter)] was placed over each pot containing the experimental plant. Plants (4 and 5-wk-old) containing 15 fully expanded leaves were used for collection of samples.

2.3 Extraction of enzymes

Each experimental plant (L. adscendens or L. parviflora or L. octovalvis) was used for collection of leaf tissues from undamaged (UD) and insect damaged (ID) plants, i.e., plants on which 5 adult females had fed on continuously for 6 h or 48 h. Insect damaged plants (immediately after feeding by adults) were used for collection of leaf tissues.

Infested leaves of plants after insect feeding were abscised from of each Ludwigia species (L. adscendens or L. parviflora or L. octovalvis) followed by removal of main veins from the leaves. Leaves of undamaged plants were sampled as controls. Separate plants from each of the feeding damage treatment (plants 6 h or 48 h after feeding by A. cyanea) and the undamaged plants (control) were individually assayed throughout the experiment.

2.4 Extraction and determination of enzymatic antioxidants

CAT, SOD, and APOX were estimated according to Snell and Snell (1971), Giannopolitis and Ries (1977), and Nakano and Asada (1981), respectively, and the enzyme activities were expressed as enzyme Unit min−1 g−1 dry leaf tissue according to Fick and Qualset (1975).

Glutathione-S-tranferases (GST) activity was determined using 1-chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene (CDNB) as a substrate by the method described by Habig et al. (1974), and activity of GST was expressed as nmol CDNB min−1 g−1 dry leaf tissue.

2.5 Extraction and estimation of peroxidase to phenolic substrates

The activity of peroxidases was measured using phenolic substrates such as pyrogallol (PPX) by measurement of the purpurogallin (Nakano and Asada, 1981) and guaiacol (GPX) via determination of the tetraguaiacol – a colored product of guaiacol oxidation (Maehly and Chance, 1954). Results were expressed as enzyme Unit min−1 g−1 dry leaf tissue.

2.6 Determination of protein

Protein content was determined by the method described by Bradford (1976) using bovine serum albumin as a standard.

2.7 Extraction and estimation of total thiol content

Total thiol content was measured according to the procedure of Tietze (1969).

2.8 Determination of total ROS

Total ROS was estimated by placing leaf tissue of each treatment (50 mg) in 8 mL 40 mM tris–HCl buffer (pH 7) in presence of 100 M 2′7′-dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCFDA, Sigma) at 30 °C. Supernatant was removed after 60 min and fluorescence was monitored in a fluorescence spectrometer (Perkin Elmer, Model LS 55) with excitation at 488 nm and emission at 521 nm (Simontacchi et al., 1993). In order to differentiate ROS from other long-lived substances able to react with DCFDA, additional controls were performed. For additional control, leaf tissues of each treatment were incubated without DCFDA for 60 min before fluorescence was determined. This fluorescence values was subtracted from all readings to assess the fluorescence that depend on ROS.

2.9 Determination of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)

Hydrogen peroxide was measured by the spectrophotometric method (MacNevin and Urone, 1953).

2.10 Extraction and estimation of total phenols

Total phenol content was measured by the procedure of Bray and Thorpe (1954) using catechol as a standard.

2.11 Statistical analysis

Data on total ROS, H2O2, antioxidant enzymes and biochemical parameters of UD and ID plants were analysed with one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s test (Zar, 1999).

3 Results

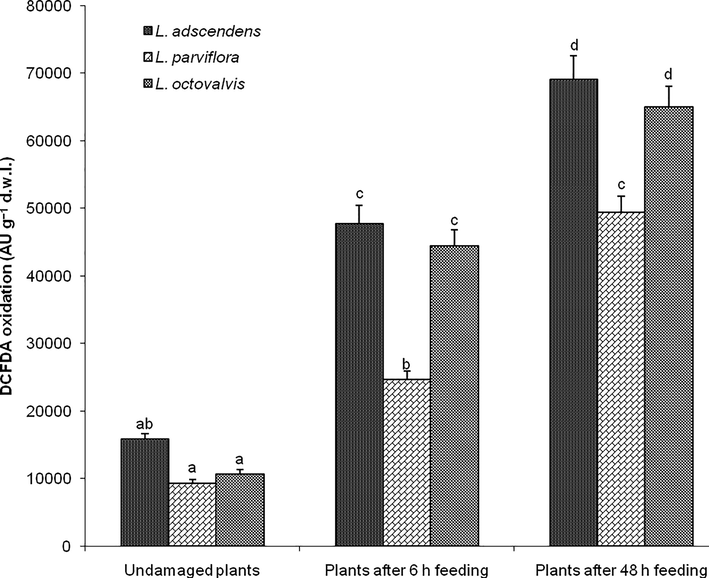

Insect feeding had a significant effect in the accumulation of total ROS in the three Ludwigia species during experimental time (F8, 36 = 109.848, P < 0.0001). Total ROS was significantly higher in the three Ludwigia species after 48 h insect feeding followed by plants after 6 h insect feeding and undamaged plants. There was no significant change in the accumulation of total ROS among the three undamaged Ludwigia species [for L. adscendens, L. parviflora, and L. octovalvis were 15865.09 ± 823.36, 9333.27 ± 501.64, and 10609.64 ± 754.14 DCFDA oxidation (AU g−1 dry leaf tissue), respectively]; whereas among the three Ludwigia species after 6 h insect feeding, total ROS was higher in L. adscendens [47758.36 ± 2619.10 DCFDA oxidation (AU g−1 dry leaf tissue)] and L. octovalvis [44486.46 ± 2358.14 DCFDA oxidation (AU g−1 dry leaf tissue)] compared to L. parviflora [24639.87 ± 1247.65 DCFDA oxidation (AU g−1 dry leaf tissue)]. Similarly among the three Ludwigia species after 48 h insect feeding, total ROS was higher in L. adscendens [69041.93 ± 3475.70 DCFDA oxidation (AU g−1 dry leaf tissue)] and L. octovalvis [65002.78 ± 3072.05 DCFDA oxidation (AU g−1 dry leaf tissue)] compared to L. parviflora [49394.37 ± 2446.40 DCFDA oxidation (AU g−1 dry leaf tissue)] (Fig. 1).

Total reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the three undamaged Ludwigia species and plants after feeding by Altica cyanea females. Bars (N = 5, Mean ± SE) with similar alphabets are not statistically different at P < 0.05; d.w.l. = dry weight of leaf tissue.

Insect feeding had a significant effect in the content of endogenous hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) in leaves of L. adscendens, L. parviflora, and L. octovalvis during experimental time (Table 1). The H2O2 content was higher in L. adscendens or L. parviflora or L. octovalvis after 48 h insect feeding followed by plants after 6 h insect feeding and undamaged plants (Table 1). Among the three undamaged Ludwigia species, H2O2 was higher in L. adscendens and L. octovalvis compared to L. parviflora. Similarly, H2O2 was higher in L. adscendens and L. octovalvis after 48 h insect feeding compared to L. parviflora after 48 h insect feeding (Table 1). CAT, SOD, APOX, GPX, and PPX were expressed in Unit g−1 d.w.l. min−1. H2O2 and thiol were expressed as µmol g−1 d.w.l. Protein was expressed as mg g−1 d.w.l. d.w.l. means of dry weight of leaf tissue.

Control

Plants after 6 h feeding by A. cyanea

Plants after 48 h feeding by A. cyanea

Parameters

L. adscendens

L. parviflora

L. octovalvis

L. adscendens

L. parviflora

L. octovalvis

L. adscendens

L. parviflora

L. octovalvis

F 8,36

P

CAT

3.88 ± 0.09a

3.10 ± 0.06bc

2.94 ± 0.05c

4.36 ± 0.07d

3.48 ± 0.11b

3.51 ± 0.09b

5.90 ± 0.23e

4.64 ± 0.22d

4.63 ± 0.24d

38.961

0.0001

SOD

4.90 ± 0.19a

1.49 ± 0.09b

2.35 ± 0.19c

7.06 ± 0.30d

2.20 ± 0.19c

4.31 ± 0.38a

9.63 ± 0.60e

5.54 ± 0.16a

5.61 ± 0.23a

63.548

0.0001

APOX

2.11 ± 0.10a

1.83 ± 0.13a

1.74 ± 0.09a

3.18 ± 0.13b

3.19 ± 0.08b

2.60 ± 0.08c

4.19 ± 0.10d

3.89 ± 0.11d

3.76 ± 0.11d

74.163

0.0001

GPX

0.48 ± 0.07a

0.42 ± 0.05a

0.39 ± 0.03a

0.58 ± 0.04ac

0.48 ± 0.04a

0.45 ± 0.02a

0.72 ± 0.05b

0.62 ± 0.04bc

0.52 ± 0.04ac

5.364

0.0001

PPX

3.19 ± 0.15a

2.44 ± 0.15b

2.07 ± 0.16b

4.15 ± 0.21c

3.40 ± 0.14a

3.07 ± 0.13a

5.69 ± 0.16d

5.65 ± 0.15d

5.10 ± 0.14d

75.109

0.0001

H2O2

72.29 ± 5.78ad

42.91 ± 3.29b

66.18 ± 2.23a

143.39 ± 8.34c

86.83 ± 5.62d

165.92 ± 8.18c

218.67 ± 15.27e

161.05 ± 6.65c

211.47 ± 7.71e

18.853

0.0001

Thiol

6.90 ± 0.32a

7.57 ± 0.37af

10.89 ± 0.52b

5.14 ± 0.27c

6.36 ± 0.24a

9.05 ± 0.15d

3.45 ± 0.28e

5.05 ± 0.23c

8.10 ± 0.19f

55.499

0.0001

Protein

69.18 ± 2.68a

55.53 ± 2.41bd

64.12 ± 3.21ab

60.44 ± 4.46ab

48.91 ± 2.06cd

62.47 ± 3.99ab

48.09 ± 2.69cd

42.51 ± 2.68c

47.32 ± 2.96cd

8.693

0.0001

Phenol

3.29 ± 0.32a

3.13 ± 0.22a

3.03 ± 0.16a

5.43 ± 0.20bd

4.75 ± 0.17b

5.06 ± 0.28bd

6.77 ± 0.39c

5.76 ± 0.22d

6.79 ± 0.36c

28.081

0.0001

The activities of CAT, SOD, and APOX were higher in L. adscendens or L. parviflora or L. octovalvis after 48 h insect feeding compared to undamaged plants (Table 1). Among the three undamaged Ludwigia species, CAT and SOD were higher in L. adscendens compared to L. parviflora and L. octovalvis. Similarly, CAT and SOD were higher in L. adscendens after 48 h insect feeding compared to L. parviflora and L. octovalvis after 48 h insect feeding, while APOX was similar in the three Ludwigia species after 48 h insect feeding (Table 1).

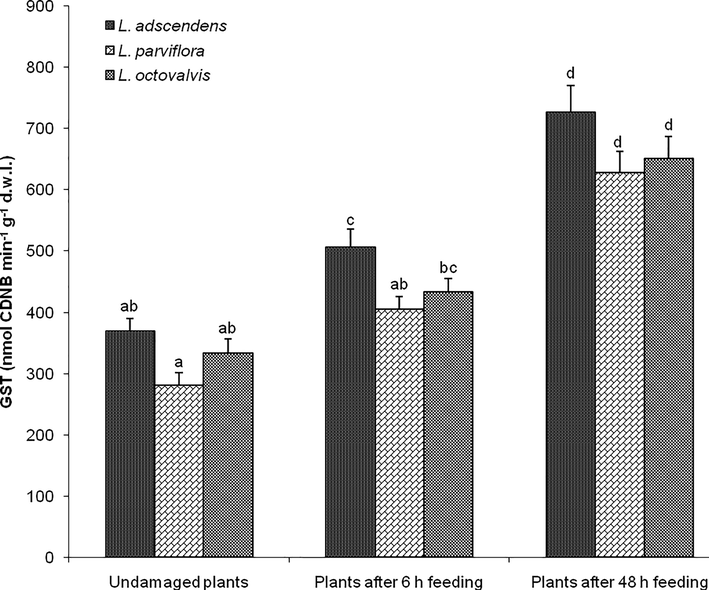

The activity of GST among the three Ludwigia species was significantly affected by insect feeding treatments compared to undamaged plants (F8, 36 = 29.054, P < 0.0001) (Fig. 2). There was no significant change in the activity of GST among the three undamaged Ludwigia species (for L. adscendens, L. parviflora, and L. octovalvis were 370.02 ± 19.73, 281.47 ± 19.52, and 334.05 ± 22.31 nmol CDNB min−1 g−1 dry leaf tissue, respectively). However, the activity of GST was higher in the three Ludwigia species after 48 h insect feeding (for L. adscendens, L. parviflora, and L. octovalvis were 726.29 ± 44.57, 628.24 ± 34.54, and 651.51 ± 35.71 nmol CDNB min−1 g−1 dry leaf tissue, respectively) compared to undamaged plants (Fig. 2).

Activity of glutathione S-transferase (GST) in the three undamaged Ludwigia species and plants after feeding by Altica cyanea females. Bars (N = 5, Mean ± SE) with similar alphabets are not statistically different at P < 0.05; d.w.l. = dry weight of leaf tissue.

Activity of peroxidase-oxidized phenolic substrates such as pyrogallol (PPX) and guaiacol (GPX) were higher in each Ludwigia species after 48 h insect feeding compared to undamaged plants (Table 1); whereas GPX were similar in the three Ludwigia species after 6 h insect feeding and undamaged plants, but PPX was higher in undamaged and insect damaged L. adscendens after 6 h insect feeding compared to L. octovalvis and L. parviflora (Table 1).

The thiol content gradually decreased from the three undamaged Ludwigia species to plants after insect feeding during experimental time (Table 1). The concentration of thiol content was lowest in plants 48 h after insect feeding followed by plants after 6 h insect feeding and undamaged plants (Table 1). Among the three undamaged Ludwigia species, thiol content was higher in L. octovalvis compared to L. adscendens and L. parviflora. Similarly among the three species of Ludwigia after 48 h insect feeding, thiol content was higher in L. octovalvis compared to L. parviflora and L. adscendens (Table 1).

The concentration of protein was lower in each Ludwigia species after 48 h insect feeding compared to undamaged plants (Table 1). The concentration of phenols was highest in the three Ludwigia species after 48 h insect feeding followed by plants after 6 h insect feeding and undamaged plants (Table 1). Among the three undamaged Ludwigia species, the concentration of phenols did not differ significantly; whereas the concentration of phenols were higher in L. adscendens and L. octovalvis after 48 h insect feeding compared to L. parviflora after 48 h insect feeding (Table 1).

4 Discussion

ROS are generated as a byproduct of natural metabolism in plant cells and a steady level is maintained for the normal metabolism of plants. But, insect attack on plants results in the accumulation of ROS (Liu et al., 2010). The present study also revealed higher amount of ROS accumulation in each insect damaged Ludwigia species compared to undamaged plants, suggesting that ROS is involved in plant defense against A. cyanea attack. Liu et al. (2010) observed an increase of ROS in susceptible wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) and rice (Oryza sativa L.) plants when attacked by Hessian fly (Mayetiola destructor Say) larvae. Further, the wounding caused by A. cyanea feeding on each Ludwigia species resulted in over production of H2O2 in plants, which might be local and systemic. The present study revealed that feeding by the adults of A. cyanea on L. adscendens, L. parviflora, and L. octovalvis resulted a significant increase of H2O2 in the insect damaged plants compared to undamaged plants, indicating that these three Ludwigia species are trying to activate the defence mechanism against insect herbivory as endogenous level of H2O2 is an important indicator of redox status of plant tissues and its ability to diffuse freely allows H2O2 to play as a central role in plant defence responses. This study is in good agreement with an earlier study of feeding by the adults of Aulacophora foveicollis Lucas (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) on Solena amplexicaulis plants resulted significant increase of H2O2 to activate the defence mechanism in plants (Karmakar et al., 2018). Furthermore, Helicoverpa zea Boddie (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) larval feeding on soybean leaves (cv. Forrest or Hutcheson) resulted significant increase of H2O2 in soybean plant (Bi and Felton, 1995). This study demonstrated that among the three Ludwigia species after 48 h feeding by A. cyanea, L. adscendens and L. octovalvis had higher level of ROS and H2O2 compared to L. parviflora, indicating that A. cyanea feeding caused more stress on L. adscendens and L. octovalvis compared to L. parviflora.

SOD, the first line of defence, catalyzes the superoxide into oxygen and H2O2, and scavenges toxic free radicals generated in plants during herbivory. CAT converts the toxic and unstable ROS into less toxic and more stable components such as O2 and water (Bhattacharjee, 2012), and enhanced CAT activity in plants increases cell wall resistance, and acts as a signal for induction of defensive genes (Caverzan et al., 2012). In the present study, CAT and SOD were higher in L. adscendens after 48 h insect feeding compared to L. octovalvis or L. parviflora after 48 h insect feeding, indicating that A. cyanea caused more stress on L. adscendens compared to the other two Ludwigia species, and subsequently, L. adscendens plants generated more CAT and SOD to cope with the stress resulted due to insect herbivory. GST reduces H2O2 through ascorbate-independent thiol-mediated pathways using glutathione (GSH), thioredoxin (TRX) or glutaredoxin (GRX) as nucleophile (Meyer et al., 2012). This study revealed higher amount of GST in the three Ludwigia species after 48 h feeding by A. cyanea compared to undamaged plants, implicating that these three Ludwigia species are trying to cope with the stress resulted due to insect feeding. Higher amount of APOX in the insect damaged plants reduces in the availability of ascorbate in leaf tissues, which results in retardation of insect growth and development (Caverzan et al., 2012). Furthermore, APOX scavenges H2O2 to water, and oxidizes phenolic compounds to quinones, which deters insect feeding (Felton et al., 1994). We recorded higher amount of APOX in the three Ludwigia species after 48 h insect feeding compared to undamaged plants, indicating that these three Ludwigia species tested in this study are trying to cope with the stress resulted due to A. cyanea feeding. Cell wall peroxidase, acts as a major enzymatic system to control cellular damage, employs H2O2 during the oxidation of NADH to NAD+ and reduces toxicity of H2O2 to water (Mai et al., 2016). We observed higher activity of PPX and GPX in the three Ludwigia species after 48 h insect feeding compared to undamaged plants, which was in parallel with the accumulation of H2O2 content in plants after feeding by A. cyanea indicating that these three Ludwigia species are trying to cope with the stress caused by insect herbivory. Thiol content was higher in undamaged L. adscendens, L. parviflora, and L. octovalvis compared to insect damaged plants, indicating that H2O2 might inactivate enzymes by oxidizing their thiol groups (Bi and Felton, 1995). The depletion of thiol compounds is considered as biochemical markers of oxidative stress (Bi and Felton, 1995). We observed lower amount of protein in the three Ludwigia species after 48 h feeding by A. cyanea compared to undamaged plants, indicating that decrease in protein concentration in the damaged plants are due to insect herbivory (Sandhyarani and Usha Rani, 2013).

Plants vary widely in qualitative and quantitative differences in phenolic compounds (Awika and Rooney, 2004). Plants produce antioxidant agents caused by insect herbivory to cope with the cellular oxidative damage by detoxifying the reactive oxygen species. Phenolic compounds act as antioxidants by inactivating lipid free radicals or inhibiting hydroperoxides to break down into free radicals (Bhonwong et al., 2009). Quinones formed by oxidation of phenols bind covalently to leaf proteins, and inhibit the protein digestion in herbivores (Bhonwong et al., 2009; Gill et al., 2010; Gulsen et al., 2010). Furthermore, plants have evolved enzymes such as ascorbate peroxidases and other peroxidases by oxidizing mono- or dihydroxyphenols, which results to the formation of reactive o-quinones, and subsequently, polymerizes or forms covalent adducts with the nucleophilic groups of proteins (Bhonwong et al., 2009; Mocan et al., 2016; Mollica et al., 2017). In our study, the tolerance of three Ludwigia species after 48 h feeding by A. cyanea coincided with the leaf enrichment in total phenols while their tolerance to damage by insect feeding paralleled with an increase of activities of the enzymes, CAT, SOD, GST, APOX, GPX, and PPX. These results show concomitant stimulations in both phenolic biosynthesis and antioxidant activity in the leaf tissues of three Ludwigia species when they are attacked by A. cyanea.

5 Conclusion

The present study summarizes that an increase in the activities of CAT, SOD, GST, APOX, and peroxidases (GPX and PPX) in the three Ludwigia species (L. adscendens, L. parviflora, and L. octovalvis) after 48 h feeding by the adults of A. cyanea, while a significant increase in the accumulation of total ROS and H2O2 was observed in the damaged leaves with an increase of feeding time by A. cyanea, suggesting that these three Ludwigia species are trying to cope with the stress caused by insect herbivory. The thiol content decreased in the insect damaged Ludwigia species compared to undamaged Ludwigia species, implicating that plants are trying to cope with the stress. The concentration of phenols increased from each undamaged Ludwigia species (L. adscendens, L. parviflora, and L. octovalvis) to insect damaged Ludwigia species, suggesting that plants are trying to defence against insect herbivory as increased amount of phenols in plant tissues deter insect feeding.

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Ambarish Mukherjee and Prof. Soumen Bhattacharjee, Department of Botany, The University of Burdwan for identification of these plants and for helping in determination of ROS, respectively. This study was supported by the University Grants Commission, New Delhi, India [F. No. – 43-578/2014(SR)]. We are thankful to DST PURSE Phase-II for providing necessary instrumental facilities.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Sorghum phytochemicals and their potential impact on human health. Phytochemistry. 2004;65:1199-1221.

- [Google Scholar]

- New locality records of Chrysomelidae (Coleoptera) from Pothowar tract of the Punjab. Asian J. Agri. Biol.. 2015;3:41-45.

- [Google Scholar]

- The language of reactive oxygen species signaling in plants. J. Bot.. 2012;985298

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Defensive role of tomato polyphenol oxidases against cotton bollworm (Helicoverpa armigera) and beet armyworm (Spodoptera exigua) J. Chem. Ecol.. 2009;35:28-38.

- [Google Scholar]

- Foliar oxidative stress and insect herbivory: primary compounds, secondary metabolites, and reactive oxygen species as components of induced resistance. J. Chem. Ecol.. 1995;21:1511-1530.

- [Google Scholar]

- A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem.. 1976;72:248-254.

- [Google Scholar]

- Analysis of phenolic compounds of interest in metabolism. Meth. Biochem. Anal.. 1954;1:27-52.

- [Google Scholar]

- Plant responses to stresses: role of ascorbate peroxidase in the antioxidant protection. Genet. Mol. Biol.. 2012;35:1011-1019.

- [Google Scholar]

- Study on weed and weedy rice control by imidazolinone herbicides in CLEARFIELD™ paddy grown by imi-tolerance indica rice variety. Omonrice. 2007;15:63-67.

- [Google Scholar]

- Oxidative responses in soybean foliage to herbivory by bean leaf beetle and three-cornered alfalfa hopper. J. Chem. Ecol.. 1994;20:639-650.

- [Google Scholar]

- Genetic control of endosperm amylase activity and gibberellic acid responses in standard-height and short-statured wheats. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.. 1975;72:892-895.

- [Google Scholar]

- Superoxide dismutase: I. Occurrence in higher plants. Plant Physiol.. 1977;59:309-314.

- [Google Scholar]

- Role of oxidative enzymes in plant defenses against insect herbivory. Acta Phytopathol. Entomol. Hung.. 2010;45:277-290.

- [Google Scholar]

- Characterization of peroxidase changes in resistant and susceptible warm-season turfgrasses challenged by Blissus occiduus. Arthropod-Plant Interact.. 2010;4:45-55.

- [Google Scholar]

- Glutathione S-transferases. The first enzymatic step in mercapturic acid formation. J. Biol. Chem.. 1974;249:7130-7139.

- [Google Scholar]

- Insect herbivores associated with Ludwigia species, Oligospermum section, in their Argentine distribution. J. Insect Sci.. 2014;14:201.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antioxidant enzymes in Solena amplexicaulis (Lam.) Gandhi plants against Aulacophora foveicollis Lucas. Allelopathy J.. 2018;44:285-298.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reactive oxygen species are involved in plant defense against a gall midge. Plant Physiol.. 2010;152:985-999.

- [Google Scholar]

- Traditionally used Lathyrus species: phytochemical composition, antioxidant activity, enzyme inhibitory properties, cytotoxic effects, and in silico studies of L. czeczottianus and L. nissolia. Front. Pharmacol.. 2017;8:83.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Separation of hydrogen peroxide from organic hydroperoxides. Anal. Chem.. 1953;25:1760-1761.

- [Google Scholar]

- The involvement of peroxidases in soybean seedlings’ defense against infestation of cowpea aphid. Arthropod-Plant Interact.. 2016;10:283-292.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Fauna of British India, Including Ceylon and Burma. Coleoptera. Chrysomelidae (Galerucinae). London: Taylor and Francis; 1936.

- A high-coverage genome sequence from an archaic Denisovan individual. Science. 2012;338:222-226.

- [Google Scholar]

- The role of leaf volatiles of Ludwigia octovalvis (Jacq.) Raven in the attraction of Altica cyanea (Weber) (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) J. Chem. Ecol.. 2017;43:679-692.

- [Google Scholar]

- Long-chain alkanes and fatty acids from Ludwigia octovalvis weed leaf surface waxes as short-range attractant and ovipositional stimulant to Altica cyanea (Weber) (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) Bull. Entomol. Res.. 2017;107:391-400.

- [Google Scholar]

- Enzymatic assays and molecular modeling studies of Schisandra chinensis lignans and phenolics from fruit and leaf extracts. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem.. 2016;31:200-210.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anti-diabetic and anti-hyperlipidemic properties of Capparis spinosa L.: in vivo and in vitro evaluation of its nutraceutical potential. J. Funct. Foods. 2017;35:32-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hydrogen peroxide is scavenged by ascorbate-specific peroxidase in spinach chloroplasts. Plant Cell Physiol.. 1981;22:867-880.

- [Google Scholar]

- Life history and host specificity of Altica cyanea (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae), a potential biological control agent for water primrose, Ludwigia adscendens. Entomophaga. 1987;32:407-414.

- [Google Scholar]

- In vitro and in silico studies of mangiferin from Aphloia theiformis on key enzymes linked to diabetes type 2 and associated complications. Med. Chem.. 2017;13:633-640.

- [Google Scholar]

- Insect herbivory induced foliar oxidative stress: changes in primary compounds, secondary metabolites and reactive oxygen species in sweet potato Ipomoea batata (L) Allelopathy J.. 2013;31:157-168.

- [Google Scholar]

- Oxidative stress affects α-tocopherol content in soybean embryonic axes upon imbibition and following germination. Plant Physiol.. 1993;103:949-953.

- [Google Scholar]

- Colorimetric Methods of Analysis. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold Co.; 1971.

- Enzymic method for quantitative determination of nanogram amounts of total and oxidized glutathione: applications to mammalian blood and other tissues. Anal. Biochem.. 1969;27:502-522.

- [Google Scholar]

- Altica cyanea (Col: Chrysomelidae) for the biological control of Ludwigia prostrata (Onagraceae) in China. Trop. Pest Manag.. 1990;36:368-370.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biostatistical Analysis. New Jersey: Prentice Hall; 1999.

- Combining in vitro, in vivo and in silico approaches to evaluate nutraceutical potentials and chemical fingerprints of Moltkia aurea and Moltkia coerulea. Food Chem. Toxicol.. 2017;107:540-553.

- [Google Scholar]