A simple and efficient method for Taq DNA polymerase purification based on heat denaturation and affinity chromatography

⁎Corresponding author at: Medical Research Core Facility and Platforms, King Abdullah International Medical Research Center, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. nehdiat@ngha.med.sa (Atef Nehdi)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Taq DNA polymerase from Thermus aquaticus (Taq) is a widely used enzyme in molecular biology research and clinical diagnostics because of its utility in DNA amplification and sequencing assays. For laboratory large-scale production of enzymes, effort, time and cost are crucial factors. Here we describe a simple and efficient method for the production of high-quality recombinant Taq DNA polymerase using a combined method based on heat denaturation and nickel affinity chromatography. His-tagged Taq DNA polymerase was overexpressed in Escherichia coli and isolated in a first step by heat denaturation of the bacterial lysate, since Taq DNA polymerase is a thermo-resistant protein, it remains in the soluble fraction with a few bacterial protein contaminants. The isolated His-tagged Taq DNA polymerase was further purified by nickel-NTA chromatography leading to a high quality and purity enzyme with a comparable activity to most of commercially available counterparts. DNA-contaminated Taq DNA polymerases constitute a major concern especially during DNA amplification because they can lead to generation of non-specific products. Since Taq DNA polymerase is a DNA binding protein, it carries during purification process bacterial DNA contaminants. We treated the purified Taq DNA polymerase with DNase to end up with a high-quality DNA-free Taq DNA polymerase.

Keywords

Recombinant Taq DNA polymerase

Heat-denaturation

Affinity purification

Homegrown Taq

His-tagged Taq

1 Introduction

Since its isolation, thermo-resistant DNA polymerase from Thermus aquaticus (Taq) has been widely utilized in several molecular biology techniques: PCR, RT-qPCR and TA cloning. The high thermo-stability of the enzyme allows it to withstand repeated cycles of elevated temperatures, with a half-life of 1.6 h at 95 °C (Oktem, 2007; Pluthero, 1993). In addition, the enzyme has a high temperature optimum of 72–80 °C, thereby, increasing primers specificity and reducing production of primer dimers and non-specific PCR products (Innis, et al., 1988).

Full-length Taq DNA polymerase comprise an inherent 5′-3′ activity that enables the polymerase to cleave 5′ terminal nucleoside of double stranded DNA releasing mono and oligonucleosides (Holland, et al., 1991). This activity of the enzyme was exploited to devise real-time quantitative PCR assay systems, in which PCR product detection is achieved concomitantly with target amplification. In these assays, a non-extendable oligonucleotide probe (i.e. TaqMan probe), designed to hybridize to the PCR product, is labeled with a quencher fluorescent dye at the 3′ end and a reporter fluorescent dye at the 5′ end. When the probe is intact, the reporter and the quencher dyes are in close proximity therefore the reporter dye emission is quenched and no fluorescence signal is generated. When the probe anneals to its target sequence, it generates a substrate for Taq DNA polymerase that is cleaved by the 5′ exonuclease activity, during polymerization, releasing fluorescence. Released fluorescence increases each cycle, proportional to the amount of probe cleavage and is monitored in real-time during the PCR (Estalilla, 2000; Livak, 1995). Full-length and truncated forms (e.g. stoffel fragment) of the enzyme were efficiently cloned and expressed in Escherichia coli (E. coli) and several purification methods have been established (Pluthero, 1993; Chen, 2015; Engelke, 1990; Lawyer, 1993; Lawyer, 1989). This has dramatically reduced the cost of the enzyme; nonetheless, the expense of the enzyme to many laboratories and institutions may remain to be a burden, so in-house production of Taq DNA polymerase could be of interest especially to those conducting a large number of PCRs and sequencing assays.

For laboratory large-scale production of recombinant enzymes, effort, time and cost are crucial factors. The most widely used method of in-house production, relied on ammonium sulphate precipitation of the enzyme; the Pluthero method (Pluthero, 1993). This method saved effort but jeopardized enzyme activity; a significant amount (30–40 %) of enzyme was reported to be lost during salting out, in addition, the end product contained some bacterial DNA contamination (Chen, 2015). Bacterial DNA contamination may be a cause for the generation of false-positive PCR products. Since Taq DNA polymerase is a DNA binding enzyme, removal of residual DNA must be considered during purification. Chen and colleagues reported an improvement on the Pluthero method, they substituted ammonium sulphate for ethanol to precipitate the enzyme from the bacterial lysate and then directly resuspended the pellet in storage buffer instead of dialysis, thereby increasing yield and saving time (Chen, 2015). The group also treated the extracted Taq DNA polymerase with DNase and RNase to remove residual nucleic acid contamination. In our study, we describe an efficient, simple, rapid and low-cost purification method, based on combining heat denaturation and nickel affinity chromatography, to produce a DNA-free high-quality and purity Taq DNA polymerase with comparable activity to commercial counterparts.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Cloning, expression and purification of the His-tagged Taq

The full-length cDNA of Taq DNA polymerase (Thermus Aquaticus) (GenBank_AAA27507.1) with a C-terminal His-tag was cloned into pET28a (+) using SalI and NcoI restriction enzymes. The construct of His-Taq-pET28a (+) was transformed into BL21 (DE3) plysS E. coli strain. A single colony was inoculated into Luria-Bertani (LB) broth containing kanamycin (50ug/ml) and chloramphenicol (34ug/ml) and cultured overnight at 37 °C under shaking. Large scale culture was inoculated by adding 25 ml of the overnight culture per liter of LB broth containing antibiotics and allowed to grow at 37 °C to OD600 = 0.6. The culture was induced with 0.5 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and growth was continued for 6 h. The culture was centrifuged at 7,000 X g for 15 min, the cell pellet was re-suspended in PBS, the NaCl concentration of PBS was adjusted at a final concentration of 300 mM. The re-suspended cells were lysed by 3–5 cycles of 1 min sonication. The bacterial lysate was centrifuged at 20,000 X g for 20 min. Supernatant was treated with 5000 units TURBO DNase (Invitrogen) and 640 ug RNAse A solution (Promega) per liter and incubated at 37 °C for one hour, heated inactivation at 75 °C for 30 min was used to denature bacterial proteins and to denature DNase. Precipitation of denatured bacterial proteins was achieved by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 15 min. Supernatant containing soluble His-tagged Taq DNA polymerase was passed through a nickel-NTA (Ni-NTA Agarose, Invitrogen, USA, cat number R90115) column then washed with PBS (300 mM NaCl) containing 15 mM imidazole. This step is also important to get rid of heat-resistant RNase traces. His-tagged Taq DNA polymerase was eluted using PBS (300 mM NaCl) containing 500 mM imidazole and collected in 1 ml fractions. Optical density at 280 nm was measured to confirm the presence of protein. Fractions with OD280 = 0.2 and above were pooled together and dialyzed overnight at 4 °C against storage buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.2), 50 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM PMSF, 1 mM DTT, 0.05 % CHAPS and 50 % glycerol). Aliquots from each step of the expression and purification were collected and loaded onto SDS-PAGE (10 % Acrylamide, acrylamide:bis [29:1]) to confirm expression and to analyze the purity of the His-tagged Taq.

2.2 PCR

A DNA oligonucleotide of 100 bp was used as a template to quantify the polymerization yield of the purified His-tagged Taq DNA polymerase in comparison to a commercial Taq DNA polymerase (Taq PCR Core Kit from Qiagen, Cat #: 201225). To assess the ability of our purified Taq DNA polymerase in amplifying different length DNA fragments we carried out PCR reactions using templates of different lengths 1–4 kb DNA. The purified enzyme was diluted in storage buffer and the dilutions were used in the PCR under standard conditions. The PCR reaction contained: 0.1 uM template, 2 uM of Forward and Reverse primers, 3 uM dNTPs (Taq PCR Core Kit from Qiagen, cat #:201225), homemade PCR reaction buffer at final concentrations of 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH8), 10 mM KCl, 10 mM (NH4)2SO4, 1ug/ml BSA, 4.5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 % Triton-X100, the volume was adjusted at 100 μl with DNase-free water. The thermo-cycling program used started with 1 cycle at 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 65 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s.

PCR assays to amplify 1 Kb, 1.5 Kb, 2 Kb, 2.5 Kb 3 Kb, 3.5 Kb, and 4 Kb DNA fragments from a plasmid template were performed in the presence of 2.5 % DMSO. These reactions were subjected to 30 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, annealing for and extension at 72 °C for 6 min and a last final cycle of extension at 72 °C for 1 min.

2.3 RNA extraction and cDNA reverse transcription

Total RNA from HEK293T cells (ATCC) was isolated using Ambion RNA Isolation Kit (Ambion, cat #: 12183020) following manufacturer instructions and RNA quantified with Nanodrop 8000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific). Isolated total RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystemns cat #: 4368814) following manufacturer instructions. The cDNA was used for subsequent quantitative PCR (qPCR) assays.

2.4 Real time quantitative PCR

The activity of the purified His-tagged Taq DNA polymerase was tested by Real-time qPCR against commercial Taq (Taq PCR Core Kit from Qiagen, cat #: 201225) and untagged Taq in homemade qPCR buffer (see above) and TaqMan Gene Expression Master mix (Applied Biosystems, cat #: 4369016). The Taq DNA polymerase in the TaqMan Master Mix was removed by filtration and this was confirmed by qPCR. qPCR assays were performed in triplicates for each sample at a total volume of 10 ul using GAPDH predesigned TaqMan Gene expression assay (Applied Biosystemns, cat #: 4,331,182 Hs02758991_g1) in MicroAmp Optical 96-well Reaction Plate. The plate was sealed and PCR amplification was performed on a QuantStudio 6 Flex Fast Real-time PCR System (Applied Biosystems).

3 Results and discussion

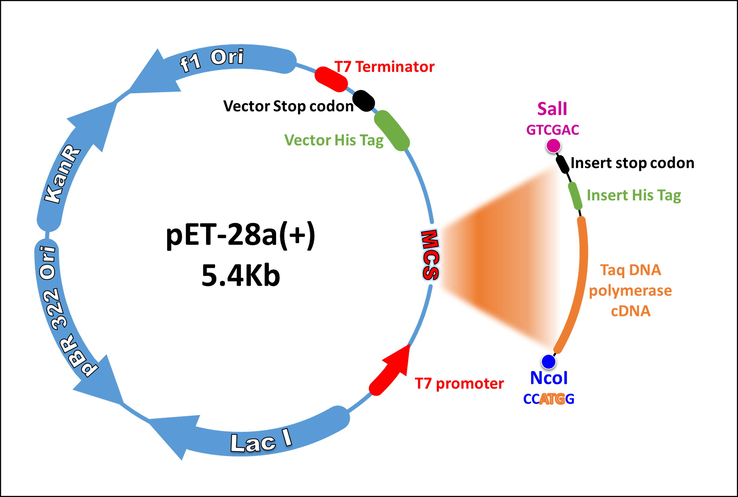

Since the discovery of Taq DNA polymerase, several methods for the expression and purification of the enzyme from E. coli have been reported (Pluthero, 1993; Engelke, 1990; Lawyer, 1993; Lawyer, 1989; Liu, 2012). In this study, we describe a purification method that lead to the production of high quantity/quality Taq. We designed a Taq DNA polymerase construct in which a DNA sequence coding for a His-tag was inserted C-terminally downstream of the full-length Taq DNA polymerase cDNA gene, followed by a stop codon and this was cloned into pET28a (+) expression vector using SalI and NcoI restriction sites (Addgene) (Fig. 1, and supplementary document 1). We chose to insert the His-tag at the C-terminus for two reasons i) to avoid the selection of truncated forms of the protein due to incomplete translation and ii) to avoid interfering with N-terminus domain that harbors the 5′-3′ exonuclease activity needed for TaqMan-based real-time qPCR. The construct was transformed into BL21 pLysS E. coli strain and overexpression of the enzyme was induced by IPTG. The full-length Taq DNA polymerase gene encodes a 94 KDa protein. SDS-PAGE analysis of aliquots from the transformed E. coli before (Fig. 2: Lane 1) and after 6 h of growth at 37 °C after IPTG induction (Fig. 2: lane 2) confirm the overproduction of Taq DNA polymerase as indicated by higher intensity band at the expected size.

-

His-Taq- pET28(a) construct map. The full-length cDNA of Taq DNA polymerase with C-terminal histidine tag sequence was cloned into pET28a (+) vector using SalI and NcoI restriction sites (Addgene).

-

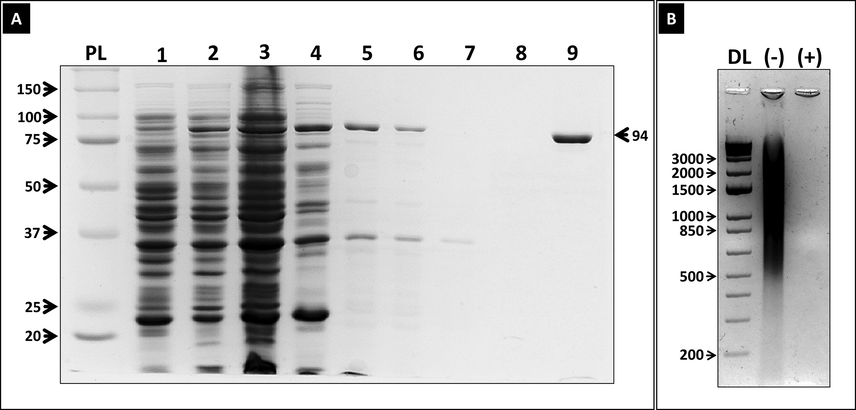

His-Tagged Taq DNA polymerase expression in BL21 pLysS and purification by heat treatment and Ni-NTA chromatography vs purification by ethanol precipitation. (A) SDS-PAGE (10 %) analysis with Coomassie staining to visualize the protein expression in Taq-His-pET28 transformed BL21pLysS from several stages of purification. (Lane 1): protein expression in Taq-His-pET28 transformed BL21pLysS before IPTG induction. (Lane 2): protein expression 6 h after IPTG induction. (Lane 3): crude lysate, (Lane 4): soluble fraction of crude lysate after centrifugation. (Lane 5): soluble fraction following 30 min heat denaturation at 75 °C of soluble lysate. (Lane 6): His-tagged Taq DNA polymerase purified by ethanol precipitation method; (Lane 7): flow through fraction after passing the heat denatured soluble fraction (in lane 5) through Ni-NTA column; (lane 8): wash with 15 mM imidazole; (lane 9): eluted fraction with 500 mM imidazole. PM: Protein Markers (B) 1 % agarose gel to stained with SybrSafe showing DNase and RNase treatment of the purified His-tagged Taq. (-): before treatment; (+): after treatment; DL: 1 Kb DNA ladder.

After 6 h of IPTG induction at 37 °C, the cells were lysed by sonication. Reported purification methods utilized the thermostability of the enzyme in order to heat denature protein contaminants, leaving Taq DNA polymerase intact in the supernatant. However, it was shown that other heat-resistant bacterial protein contaminants also remained soluble together with the Taq DNA polymerase. In this study, we combined this with affinity-based purification. In a first step, we incubated the bacterial lysate in a 75 °C water bath for 30 min to denature bacterial protein contaminants. The soluble fraction however still contained a significant amount of contaminants (Fig. 2A lanes 4: soluble fraction of crude lysate and 5: soluble fraction of heat-resistant proteins). A previously reported purification technique of the Taq DNA polymerase employed 55 % ethanol to precipitate the enzyme from the remaining contaminants (Chen, 2015). In our hands, this technique resulted in a significantly reduced yield of the enzyme with noticeable impurities (Fig. 2: lane 6). Instead, we employed a histidine affinity tag and nickel-NTA chromatography to further purify the isolated Taq. Our purification strategy based on the combined method of heat denaturation followed by affinity chromatography (Lanes 7–9) resulted in the recovery of most of the overexpressed Taq DNA polymerase yet with a high purity (Fig. 2: lane 9). The purified Taq DNA polymerase was dialyzed overnight against its storage buffer.

Since Taq DNA polymerase is a DNA binding protein, it carries during the purification process bacterial DNA contaminants. DNA contaminated Taq DNA polymerases constitute a major concern especially during DNA amplification because they can lead to generation of non-specific products. In order to eliminate DNA contamination, we treated the bacterial lysate with DNase and RNase for 1 h at 37 °C leading to a high-quality DNA-free Taq DNA polymerase (Fig. 2B). A reported method included this step (ie DNase treatment) on the soluble supernatant after an initial 75–80 °C incubation of the lysate, a second heat denaturation step was performed to denature DNAse and RNase (Chen, 2015). However, when we used the same protocol (two heat denaturation steps) we noticed loss in enzyme yield and activity so we performed DNase digestion directly on the bacterial lysate before proceeding with any of the aforementioned purification steps. In other words, heat denaturation was applied only once to denature both DNase and RNase enzymes and bacterial protein contaminants, thereby avoiding possible unnecessary loss in yield and activity of the Taq DNA polymerase from repeated thermal exposure.

The full-lengh Taq DNA polymerase constitutes two functional activities: a polymerase activity within the C-terminal domain and a 5′-3′ exonuclease activity within the N-terminal domain (Innis, et al., 1988). Both activities were tested in the purified His-tagged Taq DNA polymerase in comparison with commercial Taq.

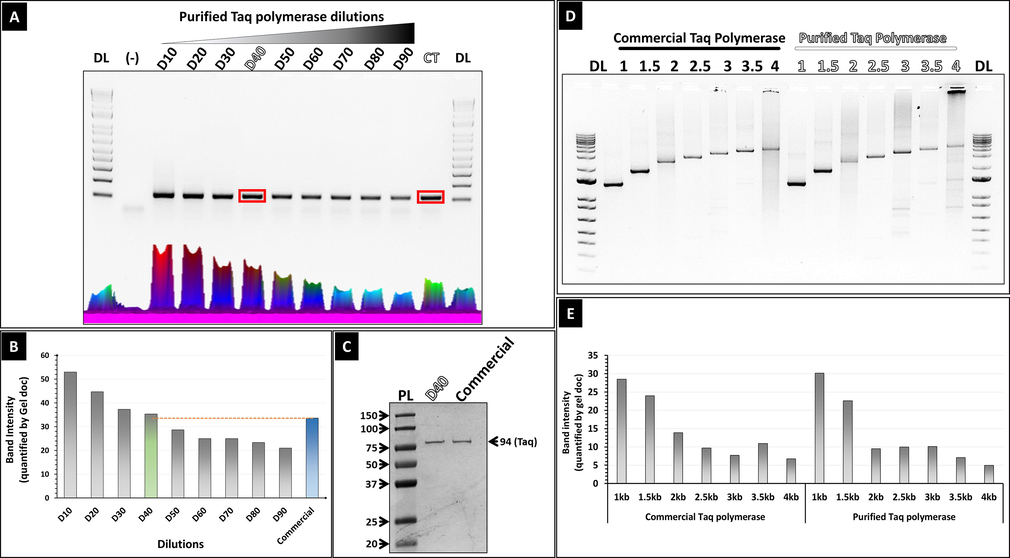

The polymerase activity of the purified enzyme was compared to commercial Taq DNA polymerase (Fig. 3) to amplify a 100 bp DNA template in a standard PCR. The purified His-tagged Taq DNA polymerase was used at multiple dilutions in the reaction mix. Agarose gel analysis (Fig. 3A) of the PCR products and subsequent quantification of the 100 bp band intensities showed that at a 1 in 40 dilution, the purified His-tagged Taq DNA polymerase gives a similar 100 bp band intensity to the commercial Taq DNA polymerase (Fig. 3B). The 1 in 40 dilution of our purified enzyme corresponds to a concentration of 100 ng/ul. SDS-PAGE analysis of equivalent volume (2 ul) of the commercial Taq polymerase and the 1 in 40 dilution of the purified His-tagged polymerase shows similar band intensities indicating similar concentration (Fig. 3C).

-

Assessment of the amplification activity of the purified His-tagged Taq. (A) Assessment of the purified His-tagged Taq DNA polymerase to amplify a short (100 bp) DNA fragment. (DL): 1 Kb DNA ladder (invitrogen); (-): negative control (PCR without the DNA template). (Lanes 1–9): PCR product using different dilutions (1/10; 1/20; 1/30; 1/40; 1/50; 1/60; 1/70; 1/80 and 1/90) of the purified His-tagged Taq; (CT): PCR product using commercial Taq. (B) Band intensity quantification of 100 bp PCR product generated in (A). (C) SDS-PAGE gel (10 %) showing the purified his-tagged Taq polymerase at 1 in 40 dilution and the commercial counterpart, loaded at equal volumes (2ul). (D) Assessment of purified His-tagged Taq, at 1 in 40 dilution, to amplify long fragments of DNA (1 Kb-4 Kb) DNA fragments from a plasmid template. (E) Band intensity quantification of PCR product generated in (D).

The polymerization ability of the purified Taq DNA polymerase was further assayed to amplify longer fragments of DNA (Fig. 3D). Agarose gel analysis of the PCR products generated from the amplification reactions using the purified his-tagged Taq DNA polymerase versus commercial Taq DNA polymerase demonstrated comparable activity as shown by band intensity quantification in Fig. 3E. The purified Taq DNA polymerase had successfully amplified DNA fragments of sizes 1 up to 4 Kb in the presence of 2.5 % DMSO.

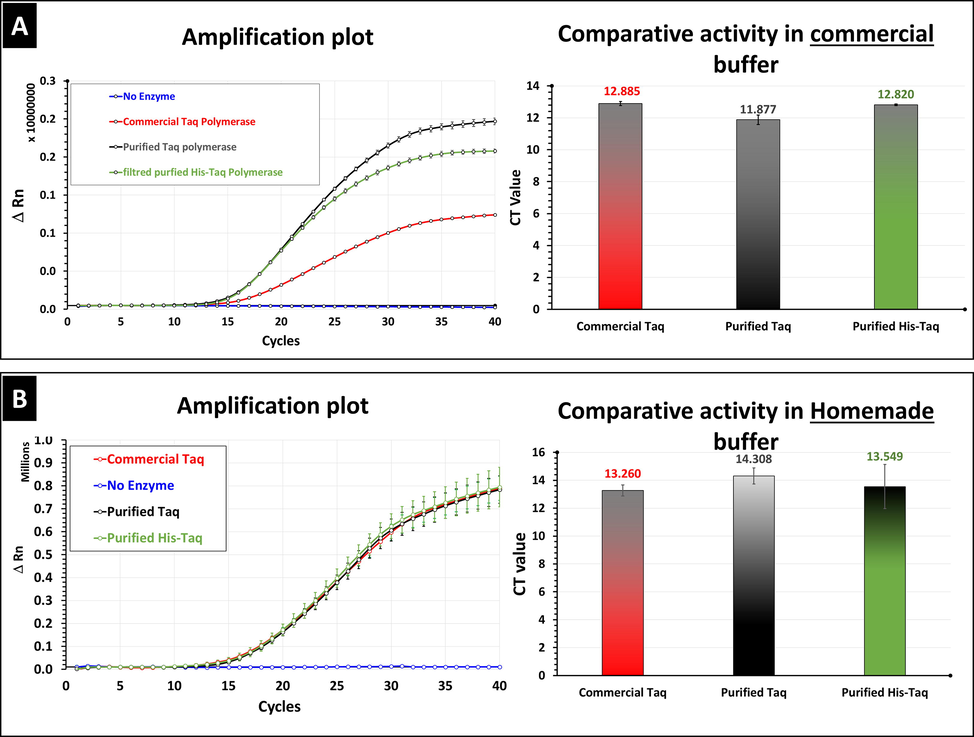

The 5′-3′ exonuclease activity of Taq DNA polymerase is crucial for TaqMan-based real-time qPCR, it is required for the cleavage of the TaqMan probe from its complementary template, during polymerization, releasing fluorescence (Holland, et al., 1991). We tested this activity in lab purified untagged and His-tagged Taq DNA polymerase in comparison with two different commercial counterparts i)Taq DNA polymerase from Qiagen and ii) Taq DNA polymerase used in TaqMan Gene Expression Master Mix. In all qPCR reactions, we used predesigned TaqMan probe and GAPDH primers. In order to compare the activity of our purified Taq DNA polymerases with the activity of Taq DNA polymerase within the TaqMan Gene Expression Master Mix (Applied Biosystems), the lab purified polymerases were added to the commercial master mix previously depleted from the commercial Taq DNA polymerase using a filter of 50KDa molecular weight cut-off. To confirm depletion, we performed a qPCR reaction with the Taq-depleted Master-Mix without addition of external Taq. The results showed no GAPDH amplification. This indicates that the master mix was successfully depleted (Fig. 4A blue line in amplification plot on the left side). This depleted Master-Mix was used to assess the activity of lab-purified polymerases alongside with a positive control reaction (non Taq-depleted TaqManMaster Mix). The reactions resulted in quite similar amplification plots and Ct values (12.885, 11.877 and 12.820) for the positive control (Commercial Taq DNA polymerase from Applied Biosystems), lab-purified untagged and His-tagged Taq DNA polymerase respectively (Fig. 4A).

-

Assessment of the 5′-3′ exonuclease activity of purified His-tagged Taq DNA polymerase using TaqMan based real-time qPCR. Comparative activity of purified his-tagged Taq DNA polymerase (green), purified untagged Taq DNA polymerase (black) and commercial Taq DNA polymerase (red) in homemade buffer represented by (A) an amplification plot curve and (B) a bar chart of the generated Ct values.

We compared also qPCR results obtained when using our purified Taq DNA polymerase to results obtained using another commercial counterpart (Taq DNA polymerase from Qiagen). In this experiment, homemade reaction buffer was used.

The qPCR reactions performed resulted in superposed amplification curves for GAPDH (Fig. 4B). Analysis of these amplification plots generated Ct values of 13.260, 14.308 and 13.549 for the positive control (Qiagen Taq DNA polymerase), lab purified untagged and His-tagged Taq DNA polymerases respectively (Fig. 4B).

These results emphasize that the purified Taq DNA polymerase have a similar activity as their commercial counterparts, moreover the added His-tag, used during affinity purification, does not seem to jeopardize neither the polymerase nor the 5′-3′ exonuclease activities. Even though the price for commercial Taq has become affordable, it may still be a burden for certain laboratories. Our developed methodology is simple, cost-effective and can be scaled up to generate large quantities of Taq polymerase. These criteria have reduced dramatically the cost of enzyme per reaction (supplementary Table 1).

4 Conclusion

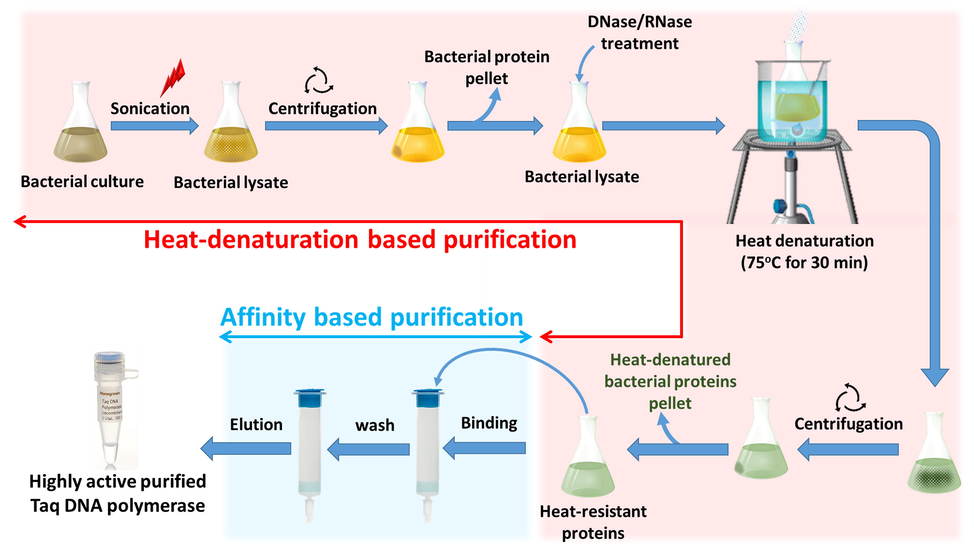

Our developed method of purification based on a combination of thermo-denaturation and affinity purification as summarized in (Fig. 5) lead to the production of a high quality and purity Taq DNA polymerase. When used in PCR and qPCR, our purified Taq polymerase gave the comparable results to commercially available counterparts in terms of double strand DNA production and Ct value. Our purification method can be of interest to laboratories and institutes, which are interested in an easy and efficient large-scale in-house production of Taq DNA polymerase without a need for expensive equipment.

- Graphical summary of the combined purification method Heat-denaturation based purification steps are shown with red background, affinity-based purification steps are shown with a blue background.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Thadeo Trivilegio for his technical assistance.

Funding

This work was supported by King Abdullah International Medical Research Center (KAIMRC) Institutional Research Grant (Grant No RC20/266/R) to AN.

Author contributions

AN conceived and designed the study and performed the overall editing of the manuscript. AN, NS and KAM performed the experiments, collected the experimental data, performed data analysis and wrote the manuscript. AN oversaw the project.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- A simple and efficient method for extraction of Taq DNA polymerase. Electron. J. Biotechnol.. 2015;18(5):355-358.

- [Google Scholar]

- Purification of Thermus aquaticus DNA polymerase expressed in Escherichia coli. Anal. Biochem.. 1990;191(2):396-400.

- [Google Scholar]

- 5′ → 3′ exonuclease-based real-time PCR assays for detecting the t(14;18)(q32;21): a survey of 162 malignant lymphomas and reactive specimens. Mod. Pathol.. 2000;13(6):661-666.

- [Google Scholar]

- Holland, P.M., et al., 1991. Detection of specific polymerase chain reaction product by utilizing the 5'----3' exonuclease activity of Thermus aquaticus DNA polymerase. In: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 88(16), pp. 7276-7280.

- Innis, M.A., et al., 1988. DNA sequencing with Thermus aquaticus DNA polymerase and direct sequencing of polymerase chain reaction-amplified DNA. In: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, vol. 85(24), pp. 9436-9440.

- Isolation, characterization, and expression in Escherichia coli of the DNA polymerase gene from Thermus aquaticus. J. Biol. Chem.. 1989;264(11):6427-6437.

- [Google Scholar]

- High-level expression, purification, and enzymatic characterization of full-length Thermus aquaticus DNA polymerase and a truncated form deficient in 5' to 3' exonuclease activity. Genome Res.. 1993;2(4):275-287.

- [Google Scholar]

- Purification of Taq DNA polymerase expressed in Escherichia coli. Yi Chuan. 2012;34(3):371-378.

- [Google Scholar]

- Oligonucleotides with fluorescent dyes at opposite ends provide a quenched probe system useful for detecting PCR product and nucleic acid hybridization. Genome Res.. 1995;4(6):357-362.

- [Google Scholar]

- Single-step purification of recombinant Thermus aquaticus DNA polymerase using DNA-aptamer immobilized novel affinity magnetic beads. Biotechnol. Prog.. 2007;23(1):146-154.

- [Google Scholar]

- Rapid purification of high-activity Taq DNA polymerase. Nucleic Acids Res.. 1993;21(20):4850-4851.

- [Google Scholar]

Appendix A

Supplementary material

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2023.102565.

Appendix A

Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article: