Translate this page into:

Sustainable nanoparticles of Non-Zero-valent iron (nZVI) production from various biological wastes

⁎Corresponding authors. Sathish.sailer@gmail.com (T. Sathish), mohd.yusuf@uregina.ca (Mohammad Yusuf) yusufshaikh.amu@gmail.com (Mohammad Yusuf)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

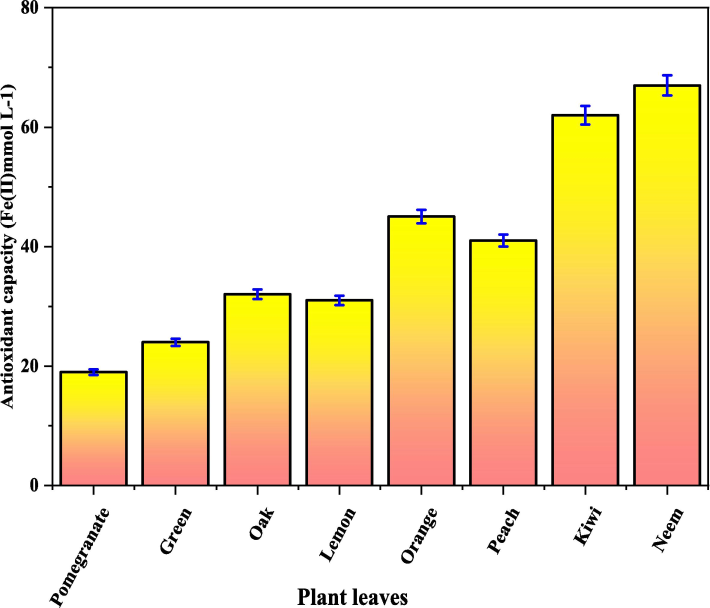

Given the growing importance of biological wastes (such as leaves from pomegranate, green tea, oak, lemon, orange, peach, kiwi, and neem) based iron nanoparticles over the past ten years and their applications in the environment, it is important to investigate new methods for nanoparticle production. Significant research has been conducted in this field as synthesizing these materials now requires careful consideration of green chemistry principles, minimization of disposal, cleaner solvents, energy efficiency, and caring precursor ingredients. The goal of this work is to evaluate the characteristics of environmentally friendly, sustainable non-zero-valent Iron (nZVI) nanoparticle production from different tree’s’ leaves. The requirements required for a product for environmental cleanup were taken into consideration when examining size, form, reactivity, and aggregation propensity. Three categories can be formed from the results of extracts in terms of antioxidant measurements (reported concentration of Fe (II)): >60 mmol/L, 20 mmol/L to 40 mmol/L, and 2 mmol/L to 5 mmol/L. Neem, oak, and green tea leaves yield the highest effects when compared to other tree leaves. It is possible to inject a different emulsion into the contaminated zone that contains nZVI, vegetable oil, and water. The best leaf extracts and operating conditions for generating sustainable nanoparticles from the bio-wastes of plant leaves must be chosen in order to use green nZVIs in environmental cleanup. These environmentally friendly nZVI nanoparticles can be used to treat impure waters to get rid of heavy metals and can use as an emulsion for paints.

Keywords

Sustainable

Waste

Environment

Pollution

Nanoparticles

Antioxidant capacity

Volume of solvent

Leaf mass ratio

Energy

1 Introduction

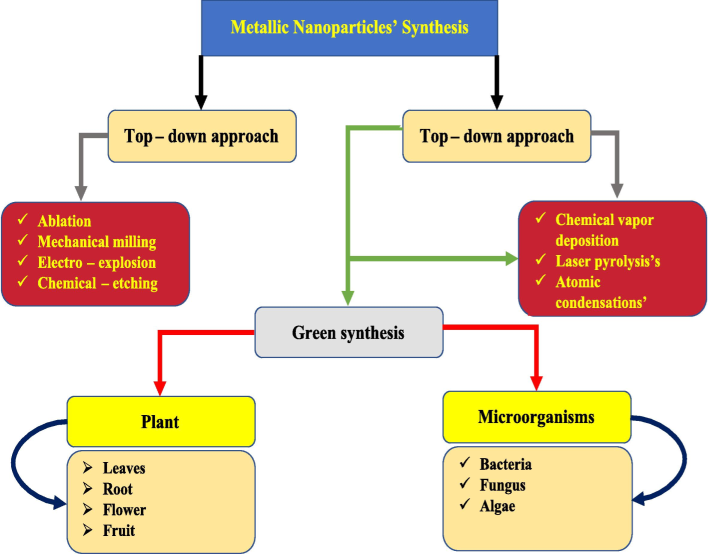

Carbon nanotubes (CNTs), graphene, metal nanoparticles, quantum dots, and other nanomaterials were all synthesised in the last ten years using a variety of cutting-edge synthesis methods. Take an interesting approach in global sustainable nanotechnology alongside these composites. Recently, a variety of technologies have been used to produce a sustainable nanomaterial with the required forms, sizes, and characteristics. The current literature examines two distinct essential moralities for the production of nanomaterials: they are top-down and bottom-up approaches. Fig. 1 illustrates the creation of nanoparticles via top/down and bottom/up metallic synthesis techniques. (see Table 1).

Making of nanoparticles by distinct synthesis approaches.

Aspect

Green Fabrication

Hydrothermal and Other Conventional Methods

Synthesis Process

Plant leaf extracts, or biological wastes, are used in Green Fabrication as stabilizing and reducing agents in place of harmful chemicals.

It functions in ambient pressure and temperature conditions, increasing the energy efficiency of the process.

It focuses on using environmentally friendly solvents and minimizing waste, adhering to the principles of green chemistry.It usually requires specialized equipment due to the high pressures and temperatures (between 150 °C and 300 °C).

It may be toxic because it makes use of organic solvents and chemical precursors.

It can create nanoparticles with exact morphological control, but the chemicals used in their production come with a higher energy cost and environmental risks.

Environmental Impact

minimal impact on the environment because it only uses ineffective solvents, water, and plant-based waste.

The procedure is in line with sustainability objectives and produces no hazardous byproducts.

It is an environmentally friendly substitute to produce nanoparticles because it significantly reduces chemical waste and carbon emissions.It uses hazardous chemicals and solvents, which, if improperly handled, can pollute the environment.

The process has a high energy requirement, which increases its carbon footprint.

It produces chemical waste, which needs to be further treated before being disposed of safely.

Cost Efficiency

cheap because only basic equipment and easily obtained plant leaves are used.

lowers operating costs by requiring less energy and equipment.

Ideal for large-scale production in settings with limited resources.Setup costs are high because high-temperature and high-pressure reactors are required.

Production costs are raised by the cost of energy and chemicals needed to maintain these conditions.

The high capital investment required may make large-scale applications less feasible in developing nations.

Nanoparticle Properties

It creates biocompatible, non-toxic nanoparticles that are perfect for use in environmental applications like water filtration.

The type of plant extract used can affect the size, shape, and reactivity of the nanoparticles, but this may lead to less uniformity when compared to chemical methods.

Although there may be differences in aggregation tendencies, plant-based stabilizers can provide some control.It produces extremely homogenous nanoparticles with exact control over size and shape, which makes it appropriate for a number of industrial and medicinal uses.

In this method, a high crystallinity in nanoparticles can increase reactivity, but it can also cause unintended toxicity in environmental applications.

Chemical surfactants can be used to control aggregation more precisely, but they may leave residues behind.

Scalability and Practical Application

Simple to scale up for large-scale production, especially in areas with a surplus of plant resources.

It can be utilized in paints and coatings without leaving behind extra chemical residues, as well as in actual environmental cleanup projects like the removal of heavy metals from contaminated water.

It is Ideal for decentralized or community-level nanoparticle production, particularly in remote or low-resource areas.The requirement for controlled environments (temperature and pressure) makes scaling up difficult.

It is mainly employed for high-value applications (such as electronics and pharmaceuticals) as opposed to extensive environmental cleanup because of the complexity and costs involved.

To guarantee that nanoparticles are free of chemical contaminants for use in the environment or in biomedicine, more post-processing may be recommended.

Comparing sustainable nZVIs with other types of nanomaterials, they are crucial to nanotechnology. (Bhattacharya et al., 2013) The use of nZVIs in Permeable Reactivity Barriers (PRBs) for groundwater, wastewater treatment, gaseous streams, soil, and sediments in coastal areas began in the early 1980s. Thats why heavy chromium metals, organochlorine insecticides, and trichloroethylene among the chlorinated compound are frequently found contaminated with nZVIs. As the field of nanotechnology has gained prominence, more studies and applications of nanoscale zero-valent iron have been conducted.

Li et al. (2006) investigated bottom/up methods linked with a top/down approach for safety concerns resulting from sodium borohydride's toxicity. The outcome of their propensity to form huge agglomerates rapidly and to a great degree, they have a diminished reactivity and degradation rate. The utilization of appropriate capping agents, such as 'greener' solvents and dropping agents, was experimentally investigated by Hoag et al. (2009). The creation of nZVI was established, and tree leaf gives more efficient nanoparticles than wood waste.

Prasad and Elumalai (2011) examined nanoparticle preparation (silver) by utilizing leaf extraction of Polyalthia, 212 longifolia, for nanoparticle production. As a result, an average particle size of 58 nm was determined to have been attained. The process of silver nanoparticle extraction from pelargonium leaf and geranium was investigated by Shankar et al. (2003). This allowed for the rapid creation of nanoparticles with dimensions that were generally stable between 16 nm and 40 nm.

Safaepour et al. (2009) examined the monoterpene alcohol origin of different leaves of plants, and geraniol (C10H18O) was used to extract the nanoparticles. The silver nitrate from the plants produces homogeneously formed nanoparticles of silver in size difference of about 1–10 nm. Kaviya et al. (2011) Investigated a nanomaterial synthesis through Crossandra leaf extract. The result of the leaf concentration of leaf affects nanoparticle production.

Pasinszki and Krebsz (2020) investigated the synthesis and application of nZVI nanoparticles from the plant leaf. Hence the different sizes of nanoparticles are accomplished through an exciting segment on particle poisonousness. The category and nature of electronegativity of impurities that need to be eliminated. These primary factors need to determine how nZVI will go about cleaning the location was carried out (Palani et al., 2023).

Valipour et al. (2016) experimentally investigated whether rock of phosphate, triple superphosphate (TS), and two phosphorus amendments clean up lead, cadmium, nickel, and copper in four. The result of TS system was reducing the Pb and Cd in the nanoparticles, hence greater the availability of Ni. Yadegari et al. (2018) Examined the impact Over two seasons on developing purslane plants to minimize heavy metal contamination in lands with Nickel and Cadmium. These all influence the soil with impacts on purslane's physical and morphological characteristics.

De et al. (2017) used the existing marketable nZVI Nanofer 25S to change depending on coastal soils polluted through heavy metals in coastal zones. Heavy metals polluted the sediments, and nZVI had the potential to effectively lower levels of heavy metal pollution in sediments. Vasarevicius et al. (2019) investigated the possibility of clearing contamination of lead, nickel, copper, and cadmium from soil samples. The results of remediation stages for individual and successive mixes of metals such as Copper, nickel, and lead as well as mixtures of cadmium, copper, nickel, and lead using different combinations through nZVI weights.

Wang and Zhang (1997) experimentally investigated a production method using biological synthesis and Borohydride overreaction using iron two and three salts. They concluded that the flammable hydrogen was produced during the investigation; hence they reduced the extraction reaction, and the degradation efficiency was greater. Using greener solvent for the extraction of green tea leaves, pomegranate leaves, and oolong tea leaves with high antioxidant capacities was investigated by Chrysochoou et al. (2012). The presence of antioxidant capacities of the leaves suitable for dipping agent for nZVI production

Smuleac et al. (2011) Proposed a synthesis mechanism for Fe2+ along with polyphenol and different compounds. Result of Fe3+ synthesis with polyphenols via following wide-ranging reaction (1). Nadagouda et al. (2010) Suggested a synthesis of Fe nanoparticles dropped with polyphenol and additional compounds. Hence the antioxidant capacities of nanoparticles were increased, and system efficiency was greater than in other studies.

Machado et al. (2013) Experimentally investigated an extraction procedure for nanoparticle production by utilizing tree leaves. 3.7 g of a leaf was weighed and added with 100 mL of water. Therefore, the cherry and oak leaves in the flask need to be heated to 80 °C for an hour. It is the result of efforts to create a nanoparticle with high efficiency. Nadagouda et al. (2008) Investigated a synthesis of nZVI at different sizes. The greater specific surface area of iron nanoparticles, which could lead to more reactive sites and better reactivity, is demonstrated by their smaller size.

Wang et al. (2014) examined an As (III) adsorption on modified composites with embedded iron nanoparticles made of nZVI reduced graphite oxide. Orange peel pith's findings suggest that the Langmuir model rather than the Freundlich model better matches the adsorption data. The stabilized nZVI value with montmorillonite was examined by Bhowmick et al. (2014). The leaves extract with maximum acidity is nearly 2.0 for oak. Similarly, maximum acidity of 4.0 was obtained by extracts of cherry and mulberry.

Researchers from Fajardo et al. (2012) found that introduction to nZVI nanoparticles needed minimal effect on the cellular survival of microorganisms and soil organic activities. According to Chandini et al. (2011), contact periods that are more than 60 min might lead to the degradation of alevins and impact the extraction of catechins. Raja et al., (2024) utilized Banyan Aerial Root waste to produce nanoparticles. Sathiyamoorthi et al., (2024) green synthesized the CuO nanoparticles and Palani et al. (2023) used the Ag2O nanoparticles for effective photodegradation of organic water pollutants in this research produced non-zero-valent iron (nZVI) nanoparticles from the biological wastes such as leaves Pomegranate, Green tea, Oak, Lemon Orange, Peach, Kiwi, and Neem to treat the water.

Hence the research gap is despite the growing interest in using biological waste for the production of iron nanoparticles, specifically non-zero-valent iron (nZVI), (Jasrotia et al., 2024) the research in this domain remains underdeveloped in certain key areas. There is a lack of comprehensive studies comparing the efficiency and properties of nZVI synthesized from different plant species. Additionally, while various synthesis methods have been explored, the application of green chemistry principles in producing nZVI using plant leaves has not been thoroughly investigated in terms of optimizing nanoparticle size, shape, and reactivity.

(Vasudevan et al., 2024) This study offers an eco-friendly, low-cost method of synthesizing iron nanoparticles, contributing to sustainable nanotechnology and cleaner environmental remediation practices. This study introduces an innovative approach to producing Non-Zero-Valent Iron (nZVI) nanoparticles using green synthesis techniques from biological wastes, specifically plant leaves. Utilizing biological waste species like neem, oak, and green tea as a precursor for nanoparticle production. Emphasis on green chemistry principles by reducing reliance on harmful chemicals traditionally used in nanoparticle synthesis. This novel investigation of alternative emulsion systems that involve vegetable oil and water, aims to improve their deployment in polluted areas.

The primary motivation behind conducting this study was the need for additional prior research and data regarding the synthesis of nZVI nanoparticles using various tree leaf extracts. (Yuvarajan et al., 2024) The purpose of this study was to ascertain whether or not various tree leaf varieties are suitable for the production of extracts that can reduce iron (III) to produce nanoparticles of zero-valent iron (nZVI). The following were the objectives of this study: i) to determine the optimal extraction conditions by examining the extraction process in terms of contact hours, solvent volume, and leaf molar ratio; ii) to identify tree leaf extracts with the highest antioxidant capacity; and iii) to use the extracts to start the production of nZVIs nanoparticles; iv) to determine the parameters of the adsorption kinetics for Fe(II); v) to acquire adsorbates on greens nZVI, and vi) to analyse the influence of pH on nanotechnology.

2 Materials and methods

We successfully extracted the bioactive components for a sustainable synthesis of nZVI nanoparticles from the biological wastes of various tree leaves. It can be obtained from plant waste like leaves, back relies, and stems. So, the plat components contain organic acid, vitamins, polyphenols, polysaccharides, and saponins. Thus, the components of plants are solvable (in water) and organic solvents (methanol and acetone). Then, the performance as stopping and dropping agents when responded using a solution composed mostly of iron (III) chloride as a precursor. The oxidation–reduction reaction of Fe3 + to Fe0 outcomes in the establishment of non-Zerovalent ion nanoparticles. Water: ethanol solution mixture was used as a reactant for this experiment.

2.1 Leaf preparation

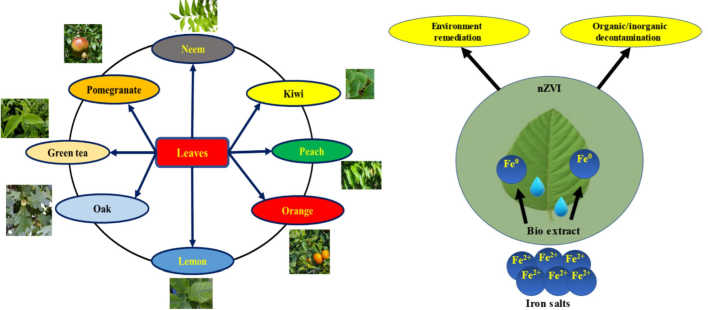

The leaves of eight distinct tree species (Neem, orange, Pomegranate, Lemon, Peach, Oak, Kiwi, and green tea) were analyzed in the fall (Fig. 2).

Eight different biological wastes of tree leaves and the Non-Zero-Valent Iron (nZVI) nanoparticle production.

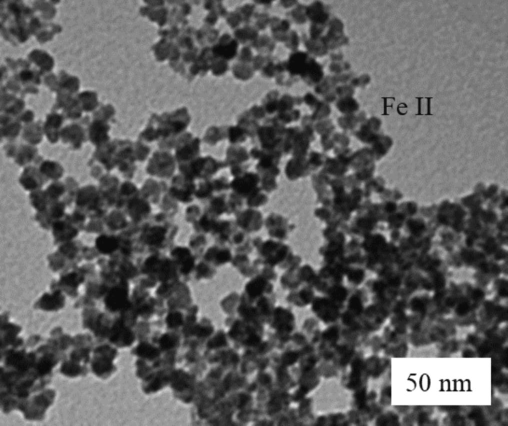

Thus, a commercial kitchen chopper milled the leaf wastage from a sustainable environment. A 4-mm sieve separated the chopped leaves below 4 mm sizes used for this investigation. Each leaf sample checks the moisture content using a Kern MLS50-3 moisture Analyzer for gives before extraction. Nanoparticle morphology and size were characterized after synthesis employing Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) as shown in Fig. 3. The plant leaves are pre-heated up to 50 ℃ for 24 h.

TEM image of the nanoparticles.

2.2 Energy of extract

Greater the energy of all leaf extractions was familiar to a similar rate (via dilution) to ensure the manufacture of similar quantities of nZVI, which allowed the value of nZVIs for different types of leaves to be compared. Therefore, to lessen the effectiveness of the leaf extracts, the “ferric reducing antioxidant power” (FRAP) method was employed. To determine how long the reaction took, the absorbance at 595 nm was measured after 30 min. The calibration curve (r = 0.8) was made using six iron (II) samples ranging in value from 10 to 3500 mol/L. Because polyphenols have a major impact on the antioxidant properties of ISO:2005, the total phenolic concentration in the extracts made using improved techniques was evaluated using the Folin-Ciocalteu method. Three gallic acid standards (ranging from 5 to 70 mol/L; r = 0.8) were used to create the calibration curve.

2.3 Nanoparticles synthesis

Hence, two approaches to creating nanoparticles from a sustainable environment are typically involved. They are top/down and bottom/up approaches. The reduced size is suitable for starting material for creating the nZVIs Nanoparticles. Size can be reduced by a variety of chemical and physical processes. Since a nanoparticle's structure greatly affects the particle's surface chemistry and other physical features, top/down production methods significantly impair the product's surface structure. The leaves used to create metal nanoparticles are depicted in Fig. 2.

2.4 pH analysis

The Digital pH meter Systronics was used to measure the solutions pH values and the leaves extraction. The pH of the reduced solution of Nanoparticle synthesized extraction was about 3.1.

2.5 Reactivity of nZVI

nZVI's capacity to breakdown some toxins in a sustainable environment for environmental cleanup is dependent on its reactivity. In order to assess and forecast the performance of the nZVI, this parameter is therefore crucial. Each reactivity was analyzed by tracking the extent of each nZVI's reaction with a mixture containing 2 mg /L chromium (VI). The diphenyl carbazide method measured the quantity of chromium (VI) (EPA,1992). Twelve chromium (VI) values with absorptions ranging from 0.05 to 2.5 mg /L (r = 0.9) were used to establish a calibration plot. By incorporating two mL of extracts in 150 L of an iron (III) solution, the ability of extracts to create nZVIs was measured and compared based on nanoparticle size. For testing the efficacy of nZVI production from a sustainable environment, one extract was selected from each of the three groups (Neem, Pomegranate, Green tea, and Lemon) described above.

3 Results and discussions

Eight different plant leaves were extracted in this experiment to create nZVI nanoparticles. As a result, when plant leaves are combined with solutions, the Fe2+ ions are reduced into Fe0+ ions. Accordingly, the structure of the recycled aggregate is affected by the physiochemical properties of the solution (the natural extract). It implies that detected nanostructures are associated with leaf type, specifically its origin, development period, moisture levels, soil fertility, pH, and stress factors such as light intensity and temperature. The amount of moisture on a plant's leaves is crucial in extracting the reaction's solution.

3.1 Moisture content in leaves

The achievement of an affordable and efficient process is just as important as the environmental objective. It is important to investigate how the moisture content of each leaf influences the extraction's antioxidant capacity. After the leaves were pre-dried for 24 h at 50 °C, measurements were taken to ascertain their moisture content. According to Table 2′s second column, pre-dried leaves had moisture content ranging from 1.5 to 80 %.

Plant leaves Samples

Interaction duration (Min)

Solvent Volume; leaf mass ratio

Moisture content (%± SD)

Pomegranate

50

0.7

3.2 ± 0.5

Green tea

30

0.9

10.1 ± 0.5

Oak

50

1.2

5.8 ± 2

Lemon

30

2.9

7.5 ± 0.8

Orange

20

0.8

5.9 ± 0.3

Peach

30

2.1

8.5 ± 0.6

Kiwi

40

2.4

10.2 ± 2.5

Neem

20

0.8

9.1 ± 0.1

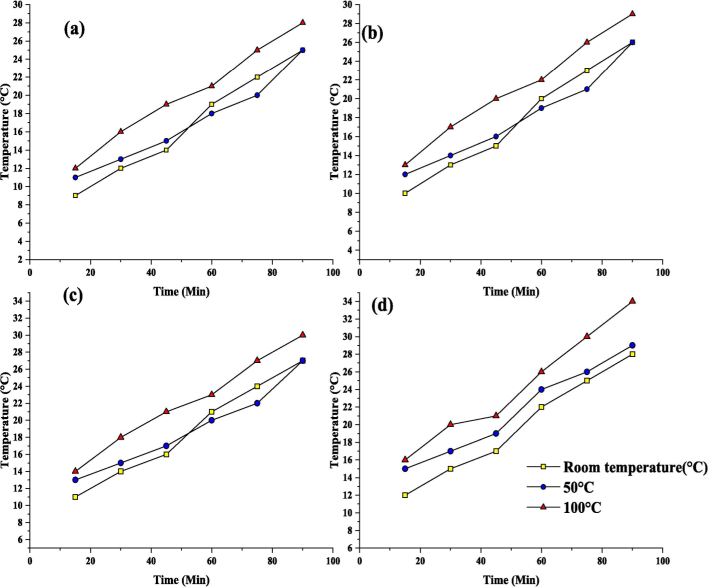

2.5 g of a leaf was weighed for these experiments, then transported to 200 mL (in an Erlenmeyer flask) with 60 mL water. The flask was subjected to 100 min at room temperature, 50 °C, and 100 °C. Samples were taken for this experiment every 15 min to show the variation of the various plant leaves

Extractions were performed at three various temperatures ranging from room temperature, 50 °C, and 100 °C for 100 min. It was predicted that the greatest extraction results would be at the highest temperature since, at this point in the process, antioxidants would not be degraded significantly. In terms of extraction time, a 15-minute treatment was adequate to extract almost all of the antioxidants from eight various plant leaves. There is no benefit to be gained by extracting for more than 15 min in terms of antioxidant capacity.

In fact, contact durations longer than 60 min may deteriorate the quality of alevins, reducing the efficiency with which the catechins are extracted. Fig. 4 and Fig. 5 show the variation of antioxidant capacity concerning the time duration for Pologrande, Green tea, Oak, Lemon, Orange, Peach, Kiwi, and Neem leaves. Such extended contact durations may be attributable to variables that restrict mass transfer, solid form internal barriers, and chemicals from leaves to an aqueous medium. “Shape” refers to the morphology of the nanoparticles formed during the extraction process. In nanoparticle synthesis, morphology can be spherical, cubic, rod-shaped, or irregular, and it plays a crucial role in determining the properties of the particles such as surface area, reactivity, and stability.

Extraction shapes for (a) Pomegranate, (b) Green tea, (c) Oak, and (d) Lemon.

Extraction shapes for (a) Orange, (b) Peach, (c) Kiwi, and (d) Neem.

It considered the consequences of extractions that used plant leaves in a dry environment. Leaves may be classified into one of three groups based on the level of antioxidants they contain: >35 mmol/L for leaves pre-dried. Compared with the leaves of other plants, the antioxidant capacity of the Neem and Green Tea extracts was the greatest, suggesting that these two plant leaves would be better for the sustainability of nZVIs.

3.2 The volume of solvent; leaf mass ratio

Using chosen extracted temperatures and interaction time, various Volumes of solvent; leaf mass ratio was investigated to categorize which ratio leads to a more effective extraction from eight different plant leaves. These extractions will be carried out in batch operations. It is crucial to determine the lowest effective concentration at which the weight of leaves produces the greatest extractions to enhance the global process regarding nZVI nanoparticle production. Four Volumes of solvent; leaf mass ratios were studied at a leaf of: 0.5; 1; 1.5; and 2 g per 60 mL water.

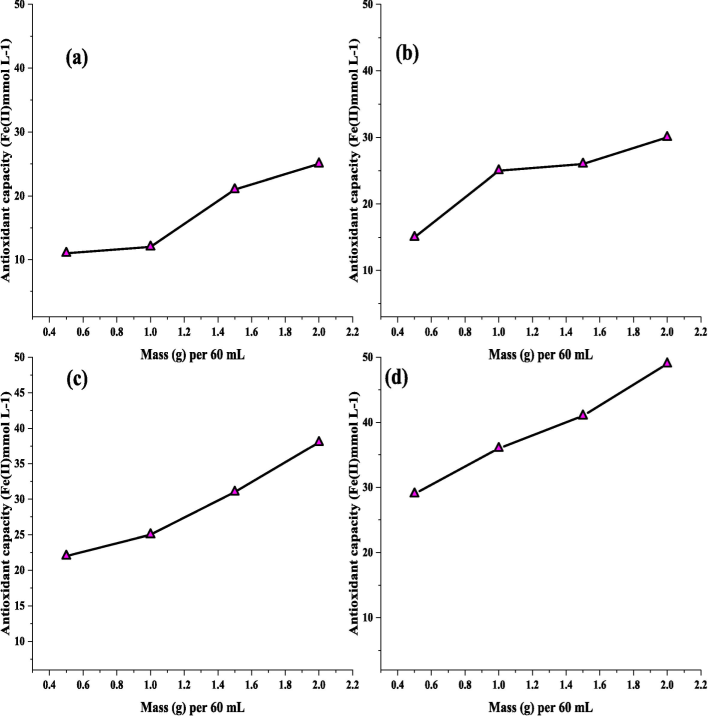

Fig. 6 and Fig. 7 show that the antioxidant capacity was varied with respect to the mass volume of the leaf per 60 mL. A relation between the volume and mass ratio along with antioxidant capacity was detected over the entire study. The Orange, Peach, Kiwi, and Neem tree leaves demonstrate a ratio is more than a certain threshold, a minor there is dispersion from linearity, which predicts that efficiency will be marginally reduced.

Extraction shapes by various Volumes of solvent; mass of leaf ratio for; (a) Pomegranate, (b) Green tea, (c) Oak, and (d) Lemon.

Extraction profiles using different Volumes of solvent; leaf mass ratio (a) Orange, (b) Peach, (c) Kiwi, and (d) Neem.

A similar explanation can be ended for outlines. Following this stage of work, it’s feasible to determine the most advantageous abstraction situations for manufacturing the richest abstracts utilizing selected leaves to form a greater number of nZVI nanoparticles, as demonstrated in the third and fourth columns of Table 2. In summary, for most of the leaves, abstractions were further effective at 100 °C for altogether leaves with 30-min contact. The mass: volume ratios showed a larger dispersion, with the most common values being 4.36 and 0.9.

When compared to other leaves, the antioxidant capacity of Neem leaves is about 48 mmo/L at 2 g in the extraction. The maximal antioxidant capacity of Pomegranate, Green Tea, Oak, Lemon, Orange, Peach, and Kiwi is around 14, 16, 19, 22, 25, 27, and 38. mmo/L. Fig. 8 depicts the extraction profiles for pomegranate, green tea, oak, and lemon leaves using varied volumes of solvent; leaf mass ratios of around 00.5; 1; 1.5; and 2 g (leaf) per 60 mL water. Similarly, the extraction profiles for Orange, Peach, Kiwi, and Neem using varying volumes of solvent and leaf mass ratios.

Antioxidant capacity of the extracts for various tree leaves.

Tree leaf extractions that were better were achieved by using a water:ethanol mixture as the reactant. The largest percentage increases were seen in green tea leaves (80 %) and oak tree leaves (93 %). The antioxidant capacity improvements in the remaining six leaves, which had undergone greater extractions, ranged from roughly 22 % to 72 %. Based on these results, a viable option for establishing greens and an affordable way to produce nZVI is to use water with Neem leaves as an abstraction solvent. Neem leaves therefore generate nZVI more effectively than leaves from other trees.

3.3 Application of nZVI nanoparticles

Numerous businesses use recycled materials to create and market nZVI nanoparticles. These highly concentrated nanoparticles have a primary particle size of less than 100 nm. They are employed in groundwater treatment to eliminate biological contaminants and render inorganic contaminants immobile. nZVI breaks down halogenated solvents in groundwater, including poly-chlorinated hydrocarbons and methane that has been chlorinated and brominated, according to multiple studies. Certain dyes, heavy metals, and herbicides were also shown to be resistant to nZVI. nZVI can be distributed into the subsurface using a variety of carrying fluids. Among the most common are water, N2 gas, and vegetable oil. Water slurries and nZVI powder were vaccinated in a polluted area using N2 as a carrier. It makes iron powder easier to disperse underground and makes iron more easily interacting with other substances. Injecting water and vegetable oil into the contaminated zone can be combined with an alternative nZVI emulsion.

4 Conclusion

The results of this investigation showed that low-moisture, sustainable leaves yielded better extractions, indicating that the use of fallen leaves may have positive effects on procedure efficiency and cost. The best results were obtained when the extraction was conducted at 100 °C. Other factors that affected the extraction process included the optimal contact duration, leaf volume of solvent, and leaf mass ratio, which varied depending on the type of leaf. Thus, the solvent containing sustainable neem leaves yields the best results when compared to other leaves.. That is better extractions of tree leaves were obtained when a mixture of water and ethanol was used as the reactant. The largest percentage increases were seen in green tea leaves (80 %) and oak tree leaves (93 %). The antioxidant capacity improvements in the remaining six leaves, which had undergone greater extractions, ranged from roughly 22 % to 72 %. Based on these results, a viable option for establishing greens and an affordable way to produce nZVI is to use water with Neem leaves as an abstraction solvent. Neem leaves therefore generate nZVI more effectively than leaves from other trees.

As a result, the selected sustainable leaves have nanoscale dimensions, demonstrating the capability of this technology to produce sustainable nZVI nanoparticles and demonstrating its superiority over traditional manufacturing techniques in terms of cost and environmental friendliness. This nanoparticle can be used to treat impure waters, emulsify paints, and other applications.

The study only focused on a few plant species, such as neem, oak, and green tea leaves, limiting the understanding of how other plant leaves might influence nanoparticle characteristics. Future studies should investigate the potential of other plant species in producing nZVI nanoparticles with enhanced properties, broadening the scope of available sustainable resources. While the study proposes using nZVI in environmental cleanup and paints, the practical implementation and field testing of these nanoparticles in real-world scenarios are not fully explored in this phase of research. Future studies should focus on field trials of nZVI nanoparticles for environmental cleanup, such as heavy metal removal from contaminated water sources, and examine their long-term environmental and health impacts.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

T. Sathish: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. Jolly Masih: Writing – original draft, Methodology. Anirudh Gupta: Writing – review & editing, Data curation. Anuj Kumar: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation. L. Raja: Writing – review & editing, Visualization. Vikash Singh: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. Abdullah M. Al-Enizi: Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Funding acquisition. Bidhan Pandit: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis. Manish Gupta: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis. N. Senthilkumar: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis. Mohammad Yusuf: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Supervision, Formal analysis.

Acknowledgement

The authors extend their sincere appreciation to the Researchers, Supporting Project number (RSP2024R55), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia., for their support.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Role of nanotechnology in water treatment and purification: Potential applications and implications. Int. J. Chem. Sci. Technol.. 2013;3:59-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- Montmorillonite-supported nanoscale zero-valen iron removal of arsenic from aqueous solution: kinetics and mechanism. Chem. Eng. J.. 2014;243:14-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- Influence of extraction conditions on polyphenols content and cream constituents in black tea extracts. Int J Food Sci Technol. 2011;46:879-886.

- [Google Scholar]

- A comparative evaluation of hexavalent chromium treatment in contaminated soil by calcium polysulfide and green tea nanoscale zero-valent iron. J. Hazard. Mater.. 2012;43:5243-5251.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nano-scale zero valent iron (nZVI) treatment of marine sediments slightly polluted by heavy metals. Chem. Eng. Trans.. 2017;60(139–144):24.

- [Google Scholar]

- Assessing the impact of zero-valent iron (ZVI) nanotechnology on soil microbial structure and functionality: a molecular approach. Chemosphere. 2012;86:802-808.

- [Google Scholar]

- Degradation of bromothymol blue by ‘greener’ nano-scale zero-valent iron synthesized using tea polyphenols. J Mater Chem. 2009;19:8671-8677.

- [Google Scholar]

- High performance Sm substituted Ni-Zn catalysts for green hydrogen generation via Photo/Electro catalytic water splitting processes. Journal of King Saud University-Science. 2024;36(9):103426

- [Google Scholar]

- Effective photodegradation of organic water pollutants by the facile synthesis of Ag2O nanoparticles. Surfaces and Interfaces. 2023;40:103088

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Biosynthesis 703 of silver nanoparticles using Citrus sinensis peel extract and its antibacterial activ704 ity. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2011;79:594-598.

- [Google Scholar]

- Zero-valent iron nanoparticles for abatement of environmental pollutants: materials and engineering aspects. Crit Rev Solid State Mater Sci. 2006;31:111-122.

- [Google Scholar]

- Green production of zero-valent iron nanoparticles using tree leaf extracts. Sci. Total Environ.. 2013;445–446:1-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- In vitro biocompatibility of nanoscale zero valent iron particles (NZVI) synthesized using tea polyphenols. Green Chem.. 2010;12:114-122.

- [Google Scholar]

- Green synthesis of silver and palladium nanoparticles at room temperature using coffee and tea extract. Green Chem.. 2008;10:859-862.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and Application of Zero-Valent Iron Nanoparticles in Water Treatment, Environmental Remediation, Catalysis, and Their Biological Effects. Nanomaterials. 2020;10:917.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biofabrication of Ag nanoparticles using Moringa oleifera leaf extract and their antimicrobial activity. Asian Pac. J Trop Biomed. 2011;1:439-442.

- [Google Scholar]

- Study on the Effect of Nanoparticles Extracted from Banyan Aerial Root Reinforced Porcelain Filler Blended PMMA Composite. J. Inst. Eng. India Ser. D 2024

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Dinesh Babu Munuswamy, Yuvarajan Devarajan, Combustion enhancement and emission reduction in RCCI engine using green synthesized CuO nanoparticles with Cymbopogon martinii methyl ester and phytol blends. Industrial Crops and Products. 2024;218:118969

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Green synthesis of small silver nanoparticles using geraniol and its cytotoxicity against Fibrosarcoma–Wehi 164. Avicenna J Med Biotechnol. 2009;1:111-115.

- [Google Scholar]

- Geranium leaf assisted biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles. Biotechnol Prog. 2003;19:1627-1631.

- [Google Scholar]

- Green synthesis of Fe and Fe/Pd bimetallic nanoparticles in membranes for reductive degradation of chlorinated organics. J. Memb. Sci.. 2011;379:131-137.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chemical immobilization of lead, cadmium, copper, and nickel in contaminated soils by phosphate amendments. CLEAN Soil Air Water. 2016;44:572-578.

- [Google Scholar]

- Application of stabilized nano Zero Valent Iron particles for immobilization of available Cd2+, Cu2+, Ni2+, and Pb2+ ions in soil. Int. J. Environ. Res.. 2019;13:465-474.

- [Google Scholar]

- Experimental study, modeling, and parametric optimization on abrasive waterjet drilling of YSZ-coated Inconel 718 superalloy. Journal of Materials Research and Technology. 2024;29:4662-4675.

- [Google Scholar]

- Removal of As(III) and As(V) from aqueous solution using nanoscale zero valent iron-reduced graphite oxide modified composites. J. Hazard. Mater.. 2014;268:124-131.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesizing nanoscale iron particles for rapid and complete dechlorination of TCE and PCBs. Environ. Sci. Technol.. 1997;31:2154-2156.

- [Google Scholar]

- Performance of purslane (Portulaca oleracea) in nickel and cadmium contaminated soil as a heavy metals-removing crop. Iran. J. Plant Physiol.. 2018;8:2447-2455.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biodiesel Production from Shrimp Shell Lipids: Evaluating ZnO Nanoparticles as a Catalyst. Results in Engineering. 2024;4:103453

- [Google Scholar]

Appendix A

Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2024.103553.

Appendix A

Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article: