Translate this page into:

Nickel toxicology testing in alternative specimen from farm ruminants in a urban polluted environment

⁎Corresponding authors. hhyang@cyut.edu.tw (Hsi-Hsien Yang), mih786@gmail.com (Muhammad Iftikhar Hussain) iftikhar@uvigo.es (Muhammad Iftikhar Hussain)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

The impact of nickel (Ni) metal toxicity, on public health was assessed analyzing forage samples (Acacia nilotica, Zea mays, Pennisetum glaucum, Capparis decidua and Medicago sativa), soils and blood samples of cow, buffalo and sheep (blood plasma, fecal, and hair) collected from three different agro-ecological zones and analyzed through atomic absorption spectrophotometer. Results showed that nickel values differed in soil samples ranging from 4.49 to 9 to 25 mg/kg, in forages from 3.78 to 9.53 mg/kg and in animal samples from 0.65 to 2.42 mg/kg. Nickel concentration, in soil and forage samples, was below the permitted limits. Soil with the minimum nickel level was found under C. decidua while the maximum concentration was reached under the A. nilotica. Among the animals, nickel was maximum in buffaloes that grazed on the Z. mays fodder. Ni was more accumulated in feces than other body tissues. The sheep and buffaloes showed high vulnerability to Ni pollution due to the highest contamination levels at site II and III. Bioconcentration factor, pollution load index and enrichment factor were found to be higher in buffaloes than cows, respectively. The daily intake and health risk index ranged from 0.0056 to 0.0184 mg/kg/day and 0.186–0.614 mg/kg/day respectively. In short, the results of this study evidenced that Nickel-containing fertilizers should never not be used to grow forage species. Government should to lessen the toxic metal accessibility to animals. Although general values were lower than the admitted limit, nickel can be accumulated and the consume of food containing nickel can increase health risks. General monitoring of soil and vegetation pollution load, as well as the use of other non-conventional water like canal water for forage irrigation could be a sustainable solution to decrease the access of nickel in the food chain.

Keywords

Peri-urban area

Food chain

Human health risk

Livestock

Nickel

1 Introduction

Food and water are essential for the survival and wellbeing of all living organisms. The quality of these resources can have a significant impact on our health and daily life (Hussain and Qureshi 2020; Saqib et al. 2024). Water contaminated with harmful chemicals, microorganisms, or other contaminants can lead to a wide range of health problems, including gastrointestinal illness, skin irritation, and even cancer. Similarly, food products contaminated with pathogens, toxins, or other harmful substances can cause foodborne illnesses, which can be severe and even life-threatening in some cases (Wang et al. 2021; Rizwan et al. 2024). Therefore, it is essential to ensure the quality and safety of food and water to protect public health and prevent the spread of diseases. This can be achieved through various measures, including regular monitoring and testing of food and water sources, implementing strict regulations and guidelines for food and water safety, and educating the public about the importance of safe food and water practices (Ashoori et al. 2022; Ghazzal et al. 2022; Yu et al. 2024).

Nickel is considered a common trace element among emerging contaminants. It is released into the environment from both natural and industrial sources (Shahzad et al., 2018; Rahi et al., 2021; Rizwan et al. 2024). The emission of Ni into the ecosystem, notably its sedimentation in cultivated terrain, stands as a primary issue (Shukla et al., 2015). Its quantities vary between 10 and 40 ppm in the majority of grounds but surpass 1,000 ppm in serpentinite soils or terrains enriched with Ni-laden minerals (Klein et al., 2022; Yu et al. 2024). To counter oxidative damage, plants have evolved natural antioxidant defense strategies, which include the production of antioxidants and a scavenging system to regulate intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels (Kaur et al. 2019). The defense system consists of both enzymatic and non-enzymatic components. Key non-enzymatic antioxidants that play a crucial role in this system include ascorbic acid (AsA), carotenoids, flavonoids, glutathione (GSH), and tocopherols (Hamed et al., 2017; Islam et al., 2016). Several enzymes also contribute significantly to the antioxidant defense, such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), guaiacol peroxidase (GPX), and peroxidase. Enzymes of the AsA–GSH pathway, including ascorbate peroxidase (APX), monodehydroascorbate reductase (MDHAR), dehydroascorbate reductase (DHAR), glutathione S-transferase (GST), and glutathione reductase (GR), also play essential roles (Hasanuzzaman et al. 2017; Rehman et al., 2022; Ali et al., 2020). Metabolomics studies have identified numerous metabolites linked to the effects of various abiotic stress conditions. Recent advancements in biotechnological fields like transcriptomics and metabolomics offer promising insights into understanding the phytoremediation of heavy metal (HM)-contaminated soils. In a wide array of vegetal species, surplus Ni in flora cultivation medium disrupts physiologic operations, yielding harmful consequences on plant development and noxious signs, encompassing chlorosis and necrosis (Valivand et al., 2019; Ishaq et al. 2024). Augmented Ni concentrations diminished leaf aqueous potential, overall dampness content, stomatal conveyance, and vaporization pace in Populus nigra (Velikova et al., 2011). Increased Ni levels in soil disrupted various physiological processes in plants inducing toxic indications such as chlorosis and necrosis in Solanum lycopersicum (Jahan et al., 2020), Brassica oleracea (Shukla et al., 2015), and Cucurbita pepo (Valivand and Amooaghaie, 2021).

Water resources are facing a severe crisis due to various factors, including rapid population growth, industrialization, and climate change. The overexploitation of groundwater and surface water resources, coupled with pollution from human activities, has led to a significant decline in water quality and availability in many parts of the world (Hussain et al. 2020; Ishaq et al. 2024). This has resulted in water scarcity, which can have severe economic, social, and environmental impacts. To address these challenges, it is essential to adopt sustainable water management practices, including conservation, recycling, and efficient use of water resources. Moreover, policymakers and stakeholders need to collaborate in implementing regulations and policies that encourage responsible water use and effective management (Akhtar et al., 2022; Hussain et al., 2020). In the ecological system, stability in the surrounding conditions is required for the viability/continuity of living organism (Khayatzadeh and Abbasi, 2010). Any material that affects the growth and lifespan of living body is pollutant and heavy metals are considered environmental pollutants (Hussain and Qureshi 2020; Ishaq et al. 2024).

Heavy metals are a group of inorganic chemicals characterized by a density at least five times greater than that of water and exhibit metallic properties. While the term 'heavy metals' typically includes certain transition metals (such as lead, mercury, cadmium, and arsenic) and some metalloids, it does not encompass all actinides, lanthanides, and metalloids (Sharma et al., 2014). Moreover, Ali and Khan (2018) suggested that metals with an atomic number greater than 20 can be considered environmental pollutants. Heavy metals include vanadium, lead, zinc, iron, cobalt, manganese, copper, and cadmium. Contamination of food and water by these heavy metals poses significant health risks to both humans and animals. One specific example of such contamination is nickel, which can infiltrate ecosystems through various pathways, leading to serious environmental and health issues (Saqib et al. 2024). This widespread contamination necessitates the evaluation of its sources and impact. In regions like Punjab, Pakistan, where peri-urban livestock farming is prevalent, the issue of heavy metal contamination becomes particularly pertinent. Livestock farming, especially cows, buffaloes, and sheep, serves as a significant income source for smallholder farmers and offers tangible assets for farming families that can be readily converted to cash. Consequently, households engaged in peri-urban livestock farming derive a substantial portion of their earnings from the sale of livestock goods. This situation has contributed to the swift proliferation of cattle colonies near major cities without any regulatory oversight or policy interventions. Further investigation is necessary to comprehensively study the challenges, limitations, and prospects associated with this livestock farming approach at this level (Khan et al., 2013; Khan et al., 2022). Heavy metals are a group of inorganic chemicals characterized by a density at least five times greater than that of water and exhibit metallic properties. While the term 'heavy metals' typically includes certain transition metals (such as lead, mercury, cadmium, and arsenic) and some metalloids, it does not encompass all actinides, lanthanides, and metalloids (Sharma et al., 2014). Moreover, Ali and Khan (2018) suggested that metals with an atomic number greater than 20 can be considered environmental pollutants. Heavy metals include vanadium, lead, zinc, iron cobalt, manganese, copper and cadmium.

Livestock farming, particularly involving cows, buffaloes, and sheep, plays a vital role in the peri-urban regions of Punjab, Pakistan, providing smallholder farmers with significant income and readily convertible assets (Khan et al. 2013; Khan et al. 2022). The rapid expansion of cattle colonies near major cities, often unregulated, highlights the urgent need for a deeper understanding of this growing sector (Farooq, 2016; Khan et al., 2013). While peri-urban livestock farming offers economic benefits, it faces several challenges, such as poor infrastructure, inadequate management practices, low milk quality, and unregulated veterinary drug use, which pose risks to both livestock and human health (Zia et al., 2011). In districts like Jhang, where livestock farming is a primary income source, one overlooked yet critical issue is heavy metal contamination, particularly from wastewater used to irrigate forage crops. Many farmers mistakenly believe that all wastewater is beneficial, unaware of the serious health risks posed by contaminants such as Nickel. To our knowledge, no prior studies have addressed the issue of Nickel contamination in this context, including the extent of pollution, bioaccumulation processes, and potential carcinogenic risks to both livestock and the local community. This research is novel in addressing this gap, focusing on the unstudied impacts of heavy metal contamination in peri-urban livestock systems, specifically within Punjab.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study area

The temperature in study area, District Jhang, Punjab, Pakistan, varies significantly throughout the year. During the summer months, it can reach extreme highs, with temperatures often soaring up to 47 °C (117°F) in June and July. In contrast, the winter months can be quite cool, with temperatures occasionally dropping to around 9 °C (48°F) in December and January (World Weather Online).

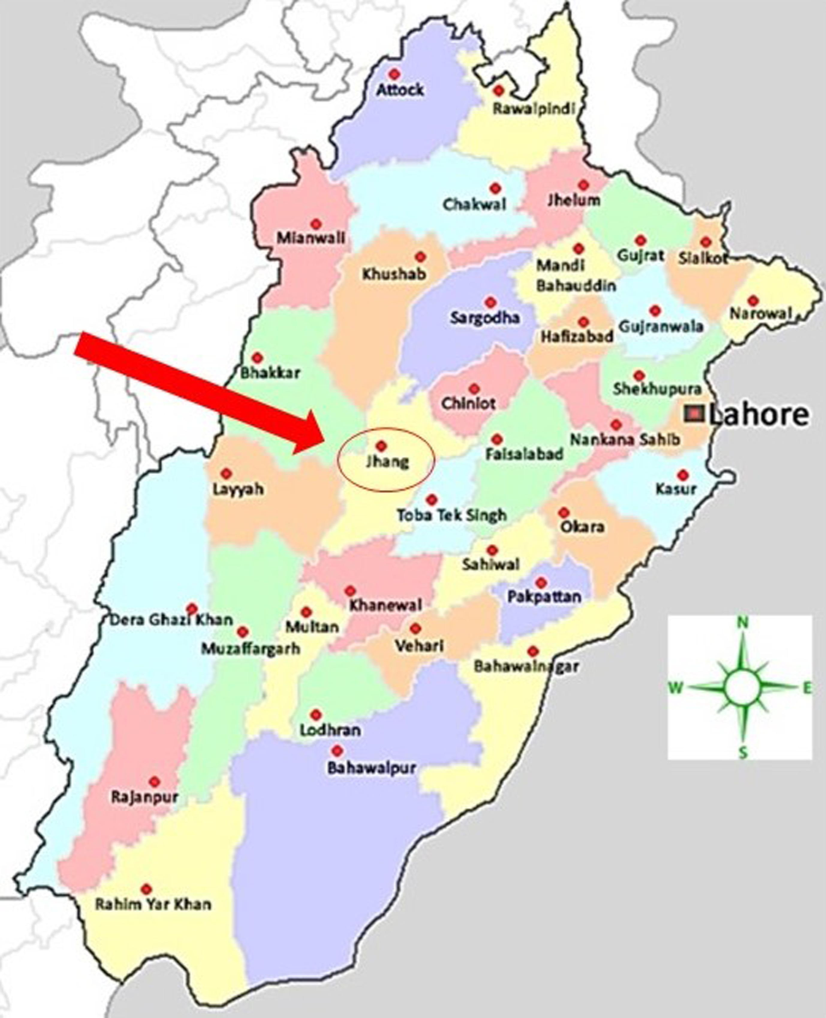

District Jhang is located at 71°-37° to 73°-13° longitudes toward east and 30°-37° to 31°–59° latitude toward North (Fig. 1). Basically three different sites in this district were selected according to the water source used to irrigate these pasture land: ground water irrigated Jhang (Jh-I) area, canal water irrigated Shorkot (Sh-II) area and sewage water irrigated Ahmad Pur Sial (Aps-III) area.

Map of study area.

2.2 Soil and forages collection

The forage plants mainly grown on the selected sites were Gum Arabic tree (Acacia nilotica L.), Corn (Zea mays L.), Pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum L.), Caper bush (Capparis decidua L.), Alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.). Soils used to grow these forage species were also collected from 0-17 cm depth. Five replicates of soil and forages were randomly selected from each site and stored in plastic bags. Forage samples were rinsed with dil. HCl and distilled water to elude the contamination and kept in open air. These open-air-dried samples were subjected to an oven for a week (75 °C) (Chen et al. 2021a).

2.3 Animal samples collection

Basically, three animal groups—cow, buffalo, and sheep were selected at all sites. At each site, 10 randomly selected healthy animals (their age between 3–5 years) from each group were selected to collect their fecal, hair and blood samples. Hair and fecal samples were collected, washed with acetone to remove contamination, and then air-dried. The samples were subjected to oven dried for 5 days (75 °C). Blood samples were collected from the jugular vein of the animals and centrifuged at 3500 rpm (12 min) to obtain blood plasma and saved at −20 °C till digestion (Hussain et al. 2021).

2.4 Wet digestion method

Laboratory equipment, chemicals and glassware such as digestion chamber, digestion tubes, electronic balance, distilled water, H2SO4 (70 %) and H2O2 (50 %), beakers, measuring cylinder, pipette and stirrers were required for this digestion method. First of all, 2 g of powdered samples were weighted through an electronic balance. Sample powder was digested with a mixture of H2SO4 and H2O2 (1:2). The mixture was heated until white fumes started evaporating. Further, drops of H2O2 were added to make a transparent solution. This solution was allowed to cool down at room temperature, and then it was filtered and a final volume of 50 ml was reached adding distilled water. (Chen et al. 2021b).

2.5 Nickel analysis

Wet digested samples of soils, plant and animals, were used to assess Ni concentration by using Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometer (Perkin-Elmer Corp. 1980). All the replicates (the number of replicates of each sample was analyzed to gain accurate results) and their mean values were also compared with international standards.

2.5.1 Bio-concentration factor (BCF)

BCF was applied to determine metal uptake in forage tissues through soil (Cui et al. 2004).

BCF soil-forage = [Ni] Fodder/[Ni] Soil.

2.5.2 Pollution load index (PLI)

PLI was applied to determine metal contamination level in soil (Liu et al. 2005).

PLI = [Ni] Soil/ [Ni] Reference value.

Ni reference value in soil is 46.75 mg/kg (Singh et al., 2010).

2.5.3 Enrichment factor (EF)

EF was applied to determine the extent to which metal enriched in these sites (Buat-Menard and Chesselet 1979)

2.5.4 Daily intake of metals (DIM)

The formula to find the daily intake of metals (DIM) is:

C metal stands for metal concentration in fodder. CF stands for conversion factor which was 0.085. D food intake stands for daily food intake which was 12.5 kg for buffalo, 12 kg for cow and 1.3 kg for sheep (Chen et al. 2021a, b; Hussain et al. 2021).

2.5.5 Health risk index (HRI)

Health risk index is calculated by the Cui et al. (2004) formula:

HRI = DIM/RfD.

DIM = Daily intake of metal.

RfD = Oral reference dose of Ni which is 0.03 mg/kg/day.

2.6 Statistical analysis

The data was statistically analyzed by using Two-way ANOVA and SPSS-16 version. Significant differences have been evaluated in all the samples as reported by Chen et al. (2021b).

3 Results

3.1 Soil analysis

The ANOVA results pointed out the significant effect of nickel in the site (p < 0.01) and the non-significant variations (p > 0.05) in the soil and site × soil (Table 1). The results of Ni concentration in the soil samples ranged from 4.49-9.25 mg/kg. The minimum concentration was present in C. decidua soil watered through ground source while the maximum concentration was present in the A. nilotica of waste watered soil gathered from the site Aps-III (Table 2). The results obtained evidence that nickel did not exceed EU (2002) measured value fixed in75 mg/kg.

Soil

Animal

Source of Variation

Degree of freedom

Mean Square

Source of Variation

Degree of freedom

Mean Square

Site

2

16.247**

Site

2

19.411***

Soil

4

5.192ns

Animal

2

0.029ns

Site * Soil

8

3.081ns

Source

2

3.095*

Forages

Site * Animal

4

1.317ns

Site

2

37.352***

Site * Source

4

1.584ns

Forage

4

13.885*

Animal * source

4

0.224ns

Site * Forage

8

1.846ns

Site * Animal * Source

8

0.553ns

Soil

Sites

A. nilotica

C. decidua

Z. mays

M. sativa

P. glaucum

Jh-I

7.933 ± 0.187

4.49 ± 0.890

8.89 ± 0.480

6.48 ± 0.580

6.03 ± 0.821

Sh-II

9.20 ± 0.350

8.87 ± 0.554

7.95 ± 0.903

8.80 ± 0.461

8.49 ± 0.711

Aps-III

9.25 ± 0.295

7.33 ± 0.456

8.55 ± 0.501

9.14 ± 0.563

8.03 ± 0.310

Forage

Jh-I

4.44 ± 0.237

3.78 ± 0.859

5.15 ± 1.01

4.31 ± 0.997

6.02 ± 0.537

Sh-II

5.37 ± 0.566

6.03 ± 1.04

8.69 ± 0.769

5.97 ± 0.872

7.91 ± 0.374

Aps-III

5.72 ± 0.835

8.31 ± 0.275

9.53 ± 0.520

6.29 ± 1.02

9.37 ± 0.899

3.2 Forage analysis

Analysis of variance evidenced significant variations of nickel in the site (p < 0.001) or forage (p < 0.05) while non-significant effect was attained in site × forage (p > 0.05) (Table 1). The Ni concentration in all the collected forage samples varied from 3.78-9.53 mg/kg. The minimum concentration was observed in the C. decidua plant at Jh-I utilizing ground water source whereas Zea mays plants showed maximum value at Aps-III watered with waste water (Table 2). Present mean concentration was found to be lower than the toxic level (10 mg/kg) of Ni given by the Kabata-Pendias (2001).

3.3 Animal analysis

The nickel analysis of variance highlighted that Site (p < 0.001) and Source (p < 0.05) significantly varied, while Animal, Site*Animal, Site*Source, Animal*Source and Site*Animal*Source didn’t varied in a significant way. (p˃0.05) (Table 1).The Ni concentration in blood plasma was 0.65–2.002 mg/l. The minimum level of nickel was detected in the blood of sheep in the Jh-I. The maximum level was instead observed in the Aps-III in the cow blood. Ni concentration ranged from 0.941-2.30 mg/kg in the hair samples. The upper level of observed range was found in the cow of Aps-III while the cow at Jh-I showed the lowest level of Ni concentration. In the faeces samples the concentration of Ni ranged from 1.01 to 2.42 mg/kg. The lowest value was observed in cow grazing in the Jh-I site, whereas the highest value was found in buffalo grazing in the Sh-(Table 3).

Animal

Sites

Blood

Hair

Feces

Cow

Jh-I

0.922 ± 0.185

0.941 ± 0.228

1.01 ± 0.201

Sh-II

1.08 ± 0.159

1.57 ± 0.255

2.01 ± 0.309

Aps-III

2.002 ± 0.239

2.30 ± 0.253

1.99 ± 0.215

Buffalo

Jh-I

0.927 ± 0.184

1.05 ± 0.177

1.10 ± 0.147

Sh-II

1.44 ± 0.207

1.57 ± 0.211

2.42 ± 0.216

Aps-III

1.22 ± 0.223

2.13 ± 0.250

1.67 ± 0.256

Sheep

Jh-I

0.65 ± 0.126

0.974 ± 0.259

1.27 ± 0.221

Sh-II

1.75 ± 0.290

1.88 ± 0.268

2.02 ± 0.248

Aps-III

1.79 ± 0.233

1.80 ± 0.250

1.48 ± 0.245

3.4 Bio-concentration factor

BCF value of Ni fluctuated in the range of 0.560–1.17. The highest amount was found in the P. glaucum of Aps-III while the lowest BCF value was detected in the A. nilotica grown in the site Jh-I (Table 4).

BCF

Sites

A. nilotica

C. decidua

Z. mays

M. sativa

P. glaucum

Jh-I

0.560

0.842

0.579

0.665

0.998

Sh-II

0.584

0.680

1.09

0.678

0.932

Aps-III

0.618

1.13

1.11

0.688

1.17

EF

Jh-I

0.076

0.114

0.078

0.090

0.135

Sh-II

0.079

0.091

0.148

0.0917

0.126

Aps-III

0.084

0.153

0.151

0.093

0.158

PLI

Jh-I

0.875

0.496

0.981

0.715

0.666

Sh-II

1.015

0.979

0.877

0.971

0.937

Aps-III

1.02

0.809

0.944

1.01

0.886

3.5 Pollution load index

PLI for Nickel ranged between 0.496 and1.02 mg/kg. The PLI index was the lowest at Jh-I location where C. decidua were cultivated, conversely, it was the highest in the site Aps-III where A. nilotica grew (Table 4).

3.6 Enrichment factor

Data analysis of Ni related to EF ranged in the following order: 0.076 to 0.158 mg/kg. The A. nilotica irrigated with ground water was minimally enriched with nickel at Jh-I while, a waste watered P. glaucum grown in Aps-III showed the maximum EF value (Table 4).

3.7 Daily intake of metal & health risk index

Daily intake level of Ni ranges from 0.0056 to 0.0184 mg/kg/day. Data obtained showed the HRI Nickel values were in the range of 0.186–0.614. Minimal intake was revealed by sheep that feed on the ground water irrigated C. decidua. On the other hand, highest intake of nickel was exposed in the buffalo nurtured on the forage Z. mays (Table 5).

Animal

Sites

A. nilotica

C. decidua

Z. mays

M. sativa

P. glaucum

DIM

Cow

Jh-I

0.0075

0.0064

0.0088

0.0073

0.0102

Sh-II

0.0091

0.0103

0.0148

0.0101

0.0134

Aps-III

0.0097

0.0141

0.0162

0.0107

0.0159

Buffalo

Jh-I

0.0086

0.0073

0.0099

0.0083

0.0116

Sh-II

0.0104

0.0116

0.0168

0.0115

0.0153

Aps-III

0.0111

0.0161

0.0184

0.0122

0.0181

Sheep

Jh-I

0.0065

0.0056

0.0076

0.0064

0.0089

Sh-II

0.0079

0.0089

0.0128

0.0088

0.0117

Aps-III

0.0084

0.0122

0.0140

0.0093

0.0138

HRI

Cow

Jh-I

0.252

0.214

0.292

0.244

0.341

Sh-II

0.304

0.342

0.492

0.338

0.448

Aps-III

0.324

0.471

0.540

0.356

0.531

Buffalo

Jh-I

0.286

0.243

0.332

0.278

0.388

Sh-II

0.346

0.388

0.560

0.384

0.509

Aps-III

0.368

0.535

0.614

0.405

0.603

Sheep

Jh-I

0.218

0.186

0.253

0.212

0.296

Sh-II

0.264

0.296

0.427

0.293

0.388

Aps-III

0.281

0.408

0.468

0.309

0.460

4 Discussion

This study highlighted that the concentration of nickel varies significantly depending on the type and composition of water used for irrigation. A lower concentration of Ni was found by Jan et al. (2010) in soil irrigated with industrial waste water (0.152 mg/kg) and by Khan et al. (2015) in soils irrigated through tubewell (0.099 mg/kg) and waste water (0.58 mg/kg). Gebrekidan et al. (2013) found a higher concentration of nickel (26 mg/kg) in soil irrigated with polluted Ginfel river water. In the same way, a great Ni concentration (35.07–160.31 mg/kg) was also detected by Mohammadi et al. (2019) in Neyshabur, Iran. Nickel can pollute ground water mainly in acidic soil that increases its mobility (Raymond et al. 2011). In another study, Rehman (2016) used a waste water (0.27–0.36 mg/kg) and ground water irrigated sites (0.06–0.15 mg/kg) of Sahiwal District that showed lowered amount of Ni distribution in soil samples against this study. Additionally, Ogundele et al. (2015) evidenced that the concentration of nickel in the control (4.33 mg/kg) and polluted sites (1.83–14.87 mg/kg) was greater than current examination. Although, fertilizer amendments and sewage sludge practices add enormous amount of Ni in the soils, the Ni mobility in soil depend upon the forms of Ni ion present in soil, profile of soil (Organic matter, clay and PH content), formation of soluble Ni-complexes and type of water used to irrigate soil (Chauhan et al.2008).

In comparison to the present survey, Reis et al. (2020) showed a lesser concentration (0.50 & 1.11 mg/kg) in two sewage contaminated farms of Brazil whereas Alghobar et al., 2014 research on the sewage irrigated grass crops exhibited a larger concentration of Ni (11–12 mg/kg) in plants. Khawla et al. (2019) studied Ni content ranges from 2.4 to 12.8 mg/kg in sewage irrigated corn that was also above than the concentration explored in this study. Conversely, Raja et al. (2015) mentioned the much lesser amount of Ni (1.75–3.33 mg/kg) accumulated in waste watered crops. Malik et al. (2017) also recorded the least level of Ni (9.433 mg/kg) in fodder crops grown around the Hudiara drain, against this work. The outcomes surpassed the present observed forages concentration were analyzed by the various studies (Ogundele et al., 2015). According to NRC (1980), the determined maximum permissible limit of nickel in forages is 5 mg/kg. The mean concentration of nickel exceeded the maximum permissible limits, recommended by the NRC (1980). Mobile nature of Ni metals induces its corporation into the plant tissues via root absorption (Antonkiewicz et al., 2016; Usman et al., 2019). Ni absorption in the tissues is highly dependent upon the pH level of soil. For example, when pH is greater than 6.7 it exist in poorly soluble form while at pH less than 6.5 its existence as soluble hydroxide can easily take up by plants (Lopez and Magnitski, 2011).

In this context, Aluc and Ekici (2019) obtained the lowered level of Ni in cattle blood as 0.028 to 0.052 mg/L against this research. High blood level of Ni (0.93–10.26) was reported by Tahir et al. (2017) in Pakistan that suggested also that a high presence of Ni in blood seemed due to their elevated concentration in forages and drinking water as take place in this study. Similarly, Orisakwe et al. (2017) conducted his research on various animals of Dareta and Abattoir locations of Nothern Nigeria. This study concluded that blood range of sheep (0.8850–3.1250 mg/kg), cattle (0.0000–2.5000 mg/kg) and goat (0.05–6.72 mg/kg) which was found to be greater than the current investigation. Milam et al. (2017) study evidenced the blood concentration in rabbit (0.012 to 0.023 mg/l) and sheep (0.013 to 0.035 mg/l) as much lower than the Ni found in this study. Similar results were also found by Tomza-Marciniak et al. (2011) in organic (0.007–0.033 μg/mL) and conventional farms (0.034–0.133 μg/mL). Gabryszuk et al. (2010) survey showed the amount of Ni in hairs of cows to be 69.45 ug/kg (0.06945 mg/kg) by raising on the organic farms which was found to be lower than the current results. Gaafar (2008) stated that the hair samples of cattle had the higher amount of Ni than buffalo hair. These findings of Gaafar (2008) were much higher than the present investigated results. Irshad et al. (2013) stated that heavy amount of metals in the feed and age factor controlled excreted amount of metals through faeces. Obtained values of this study are higher than the amount of Ni excreted by cow (0.13) and goat (0.24) collected from Ilorin, Nigeria (Adesoye et al. 2014). The achieved concentration in faecal samples was found to be greater than the Omonona et al. (2019) results detected in both dry and wet season (ND-0.11 mg/kg). Makridis et al. (2012) recorded the highest amount of Ni excreted from cow (13.47 mg/kg) and sheep (24.71 mg/kg) in Central Greece.

A lowered amount of Ni transfer from soil to forage was determined in both waste water (0.20) and treated waste water irrigated plants (0.22), (Alghobar & Suresha, 2015). Taha et al. (2013) find out the readings of Ni as 0.58–0.111 which was poorly concentrated in apropos to explicate in current survey. Current BCF values exceeded the unity level displayed that metals was absorbed by the tissues of forages. On the other hand, interpreted results of this analysis revealed to be much greater than the concluded results of other researchers (Khawla et al., 2019; Reis et al., 2020). The PLI range expressed in this survey was higher than the mean values 0.06 mg/kg given by Ripin et al. (2014). The average content of 0.181 mg/kg also expressed that present range was greater than Fosu-Mensah et al. (2017). The contamination level of Ni was found lower than the studied pollution level in soil of Botswana (Likuku et al. 2013). Reis et al. (2020) determined the lower concentration (0.28 mg/kg and 0.79 mg/kg) in the light of observed readings. Higher PLI values were also stated in Jaharia (0.47–1.68) and Gadoon Amazai (2.041) by the studies of Pandey et al. (2016) and Hussain et al. (2015); respectively. Enrichment standards of Barbieri (2016) documented the insufficient amount of Ni in the study sites, in accordance with the present survey, Inengite et al. (2015) also stated minimal enrichment of Ni in both topsoil (1.20) and bottom soil (1.15) samples but their analyzed values were greater than present outcomes. Ezemokwe et al. (2017) enriched level (1.02–13.06) was also greater than our findings. Pandey et al. (2016) found the lesser enriched value of Ni (0.98) that was lower than the concentration recorded by other researchers (Hussain et al., 2015; Likuku et al., 2013; Taha et al., 2013).

The DIM values gave the estimated amount of metal intake in animals via consumption of forages. Highest intake of Ni was observed in the buffalo animal at Aps-III with regard to cow and sheep. (Khan et al., 2016; 2017) indicated that the DIM values (0.002 to 0.003 mg/kg/day) was higher than our results. On the other hand, Khan et al. (2016) determined the lower HRI level (0.095–0.126 mg/kg/day) with regard to the present investigation, conversely, Khan et al. (2017) reported the higher HRI as 1.414–1.506 mg/kg/day. According to USEPA (2002) standards, all the HRI < 1 indicated that there was no threat to livestock health.

5 Conclusion and Future Perspectives

Nickel pollution is strongly influenced by the quality of water used for irrigation. The data show that soil samples collected from pastoral areas around Jhang had the highest nickel (Ni) concentrations, mainly due to the use of wastewater with high nickel content for irrigation. As a result, plants like Zea mays and Acacia nilotica, which lack the ability to discriminate between ions, absorbed significant amounts of nickel, accumulating it in large quantities. Conversely, the lowest nickel uptake was observed in Capparis decidua irrigated with groundwater. The highest nickel concentrations were detected in cow blood, cow hair, and buffalo feces. Despite the elevated nickel levels, the concentrations in soil and plant samples were below the critical limits set by the European Union (2002). However, the nickel levels in animal blood samples exceeded the standard limit. Although daily intake and health risk index values were below the threshold of one, although, the continuous use of wastewater in these areas poses potential health risks to animals, which could lead to the accumulation of nickel over time and eventual contamination of the food chain, impacting human health.

To mitigate this risk, it is recommended to use nickel-free water for irrigation and to avoid fertilizers, especially phosphate-based fertilizers, which are a major source of nickel contamination in soil. Additionally, providing essential mineral supplements such as copper (Cu), manganese (Mn), magnesium (Mg), zinc (Zn), iron (Fe), and calcium (Ca) can help reduce nickel uptake by plants due to ion competition, thereby preventing its entry into the food chain. Further research should focus on developing advanced bioremediation techniques and sustainable agricultural practices to minimize heavy metal accumulation in soils and crops. Investigating alternative irrigation methods and introducing nickel-resistant plant varieties could also be explored to prevent nickel contamination and protect food safety in affected regions.

Ethical Approval

Institutional Human Ethics Committee of University of Sargodha (Approval No.25-A18 IEC UOS) has allowed all the protocols used in this experiment to the commencement of the study. The authors declare that manuscript has not been published previously.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Zafar Iqbal Khan: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Fatima Ghulam Muhammad: Writing – original draft, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Kafeel Ahmad: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Mona S. Alwahibi: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Hsi-Hsien Yang: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Muhammad Ishfaq: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Methodology, Data curation, Conceptualization. Sumaira Anjum: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Software, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Kishwar Ali: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Software, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Khalid Iqbal: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Software, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Emanuele Radicetti: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Muhammad Iftikhar Hussain: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Methodology, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Funding

This research was funded by the Researchers Supporting Project, number (RSP2024R173), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. We highly appreciate the support and funding received for open access from University of Vigo / CISUG.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to the Researchers supporting project number (RSP2024R173) King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. We highly appreciate the support and funding received for open access from University of Vigo / CISUG.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Evaluation of physical properties and heavy metal composition of manure of some domestic animals. Int. J. Innov Scient. Res.. 2014;9(2):293-296.

- [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of lead toxicity in diverse irrigation regimes and potential health implications of agriculturally grown crops in Pakistan. Agric. Water Manag.. 2022;271:107743

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of sewage water irrigation on soil properties and evaluation of the accumulation of elements in Grass crop in Mysore city, Karnataka. India. Am. J. Environ. Protect.. 2014;3(5):283-291.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of nutrients and trace metals and their enrichment factors in soil and sugarcane crop irrigated with wastewater. J. Geosci. Environ. Protect.. 2015;3(08):46-56.

- [Google Scholar]

- What are heavy metals? Long-standing controversy over the scientific use of the term ‘heavy metals’–proposal of a comprehensive definition. Toxicol. Environ. Chem.. 2018;100(1):6-19.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of rice straw, biochar and calcite on maize plant and Ni bio-availability in acidic Ni contaminated soil. J. Environ. Manage.. 2020;259:109674

- [Google Scholar]

- Investigation of heavy metal levels in blood samples of three cattle breeds in Turkey. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol.. 2019;103(5):739-744.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nickel bioaccumulation by the chosen plant species. Acta Physiol. Plant.. 2016;38(2):40.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The importance of enrichment factor (EF) and geoaccumulation index (Igeo) to evaluate the soil contamination. J. Geol. Geophys.. 2016;5(1)

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Variable influence of the atmospheric flux on the trace metal chemistry of oceanic suspended matter. Earth and Planet Sci. Lett.. 1979;42(3):399-411.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nickel: its availability and reactions in soil. J. Ind. Pollut. Control. 2008;24(1):1-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ecological risk assessment of heavy metal chromium in a contaminated pastureland area in the Central Punjab, Pakistan: soils vs plants vs ruminants. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of potential ecological risk and prediction of zinc accumulation and its transfer in soil plants and ruminants: public health implications. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Transfer of metals from soil to vegetables in an area near a smelter in Nanning. China. Environ. Int.. 2004;30(6):785-791.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of heavy metal contamination of soils alongside Awka-Enugu road, southeastern Nigeria. Asian J. Environ. Ecol.. 2017;4(1):1-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- Heavy metals concentration and distribution in soils and vegetation at Korle Lagoon area in Accra. Ghana. Cogent Environ. Sci.. 2017;3(1):1405887

- [Google Scholar]

- Accumulation of some heavy metals in hair, plasma and milk of cattle and buffaloes grazing berseem or reed plants in Egypt. Egyptian J. Animal Prod.. 2008;45(2):71-78.

- [Google Scholar]

- Toxicological assessment of heavy metals accumulated in vegetables and fruits grown in Ginfel River near Sheba Tannery, Tigray and Northern Ethiopia. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf.. 2013;95:171-178.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chromium poisoning in buffaloes in the vicinity of contaminated pastureland, Punjab. Pakistan. Sustainability. 2022;14(22):15095.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sensitivity of two green microalgae to copper stress: growth, oxidative and antioxidants analyses. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf.. 2017;144:19-25.

- [Google Scholar]

- Exogenous silicon attenuates cadmium-induced oxidative stress in Brassica napus L. by modulating AsA-GSH pathway and glyoxalase system. Front. Plant Sci.. 2017;8:1061.

- [Google Scholar]

- Crop diversification and saline water irrigation as potential strategies to save freshwater resources and reclamation of marginal soils—a review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res.. 2020;27:28695-28729.

- [Google Scholar]

- Blood, hair and feces as an indicator of environmental exposure of sheep, cow and buffalo to cobalt: a health risk perspectives. Sustainability. 2021;13:7873.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Multistatistical approaches for environmental geochemical assessment of pollutants in soils of Gadoon Amazai Industrial Estate. Pakistan. J. Soils Sediments. 2015;15(5):1119-1129.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Health risks of heavy metal exposure and microbial contamination through consumption of vegetables irrigated with treated wastewater at Dubai, UAE. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res.. 2020;27:11213-11226.

- [Google Scholar]

- Application of pollution indices for the assessment of heavy metal pollution in flood impacted soil. Int. Res. J. Pure Appl. Chem. 2015:175-189.

- [Google Scholar]

- Characterization of heavy metals in livestock manures. Pol. J. Environ. Stud.. 2013;22(4)

- [Google Scholar]

- Nickel contamination, toxicity, tolerance, and remediation approaches in terrestrial biota. In: Bio-organic Amendments for Heavy Metal Remediation. Elsevier; 2024. p. :479-497.

- [Google Scholar]

- Copper-resistant bacteria reduces oxidative stress and uptake of copper in lentil plants: potential for bacterial bioremediation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res.. 2016;23:220-233.

- [Google Scholar]

- Multivariate statistical analysis of heavy metals pollution in industrial area and its comparison with relatively less polluted area: a case study from the City of Peshawar and district Dir Lower. J. Hazard. Mater.. 2010;176(1–3):609-616.

- [Google Scholar]

- Trace elements in soil and plants (3rd ed). USA: CRC Press; 2001.

- Effect of heat stress on antioxidative defense system and its amelioration by heat acclimation and salicylic acid pre-treatments in three pigeonpea genotypes. Ind. J. Agri. Biochem.. 2019;32(1):106-110.

- [Google Scholar]

- Current issues and future prospects of dairy sector in Pakistan. Sci. Technol. Dev.. 2013;32(2):126-139.

- [Google Scholar]

- Health risk assessment of heavy metals in wheat using different water qualities: implication for human health. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res.. 2016;24:947-955.

- [Google Scholar]

- High metal accumulation in Bitter gourd irrigated with sewage water can cause health hazards. Fresen. Environ. Bull.. 2017;26(7):4332-4337.

- [Google Scholar]

- Metals uptake by wastewater irrigated vegetables and their daily dietary intake in Peshawar. Pakistan. Ecol. Chem. Eng.. 2015;22(1):125-139.

- [Google Scholar]

- Accumulation of trace elements by corn (Zea mays) under irrigation with treated wastewater using different irrigation methods. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf.. 2019;170:530-537.

- [Google Scholar]

- Khayatzadeh, J. and E. Abbasi. 2010. The effects of heavy metals on aquatic animals. The 1st International Applied Geological Congress, Department of Geology, Islamic Azad University-Mashad Branch, Iran, 1: 26-28.

- Klein, C. B., Costa, M. A. X., Nordberg, G., and Costa, M. (2022). “Nickel,” in Handbook on the Toxicology of Metals, eds G. Nordberg, B. Fowler, and M. Nordberg (Cambridge, MA: Academic Press), 615–637. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.156455.

- Assessment of heavy metal enrichment and degree of contamination around the copper-nickel mine in the Selebi Phikwe Region. Eastern Botswana. Environ. Ecol. Res.. 2013;1(2):32-40.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Impacts of sewage irrigation on heavy metal distribution and contamination in Beijing, China. Environ. Int.. 2005;31:805-812.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nickel: The last of the essential micronutrients. Agronomía Colombiana. 2011;29(1):49-56.

- [Google Scholar]

- Transfer of heavy metal contaminants from animal feed to animal products. J. Agri. Sci. Technol. A. 2012;2(1A):149-154.

- [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of heavy metals in fodder crops leaves being raised with Hudiara drain water (Punjab-Pakistan) Int. J. Adv. Eng. Res. Sci.. 2017;4(5):93-102.

- [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of heavy metals (As, Cd, Cr, Cu, Ni, Pb and Zn) in blood samples of sheep and rabbits from Jimeta-Yola, Adamawa State, Nigeria. Int. J. Adv. Pharm., Biol. Chem.. 2017;6(3):160-166.

- [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of heavy metal pollution and human health risks assessment in soils around an industrial zone in Neyshabur. Iran Biol. Trace Element Res. 2019:1-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council (NRC). 1980. Mineral tolerance of domestic animals. National Research Council/National Academy of Science. Washington D.C, USA: pp. 345-363.

- Heavy metal concentrations in plants and soil along heavy traffic roads in North Central Nigeria. J. Environ. Anal. Toxicol.. 2015;5(6):1.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Heavy metal levels in water, soil, plant and faecal samples collected from the Borgu Sector of Kainji Lake National Park. Nigeria. Open Access J. Toxicol.. 2019;3(5):555625

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Horizontal and vertical distribution of heavy metals in farm produce and livestock around lead-contaminated goldmine in Dareta and Abare, Zamfara State, Northern Nigeria. J. Environ. Public Health. 2017;1–12

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ecological risk assessment of soil contamination by trace elements around coal mining area Bhanu. J. Soil Sediment. 2016;16:159-168.

- [Google Scholar]

- Toxicity of Cadmium and nickel in the context of applied activated carbon biochar for improvement in soil fertility. Saudi J. Biol. Sci.. 2021;29:742-750.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Socio-economic background of wastewater irrigation and bioaccumulation of heavy metals in crops and vegetables. Agric. Water Manag.. 2015;158:26-34.

- [Google Scholar]

- Agricultural and economic development in Pakistan and its comparison with China, India, Japan, Russia and Bangladesh. Andamios. Revista De Investigacion Social. 2016;12(01):180-188.

- [Google Scholar]

- Associative effects of activated carbon biochar and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on wheat for reducing nickel food chain bioavailability. Environ. Technol. Innov.. 2022;26:102539

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Heavy metals in soils and forage grasses irrigated with Vieira River water, Montes Claros, Brazil, contaminated with sewage wastewater. Revista Ambiente & Água. 2020;15(2)

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Analysis and pollution assessment of heavy metal in soil, Perlis. Malaysian J. Anal. Sci.. 2014;18(1):155-161.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ecological impacts and potential hazards of nickel on soil microbes, plants, and human health. Chemosphere 2024142028

- [Google Scholar]

- Alleviating effects of exogenous melatonin on nickel toxicity in two pepper genotypes. Sci. Hortic.. 2024;325:112635

- [Google Scholar]

- Nickel; whether toxic or essential for plants and environment-a review. Plant Physiol. Biochem.. 2018;132:641-651.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Biomedical implication of heavy metals induced imbalances in redox system. Biomed Res. Int. 2014:1-26.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of toxicity level of nickel on growth, photosynthetic efficiency, antioxidative enzyme, and its accumulation in cauliflower. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal.. 2015;46:2866-2876.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Health risk assessment of heavy metals via dietary intake of foodstuffs from the wastewater irrigated site of a dry tropical area of India. Food Chem. Toxicol.. 2010;48(2):611-619.

- [Google Scholar]

- Soil-plant transfer and accumulation factors for trace elements at the Blue and White Niles. J. Appl. Indust. Sci.. 2013;1(2):97-102.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparative study of heavy metals distribution in soil, forage, blood and milk. Acta Ecol. Sin.. 2017;37(3):207-212.

- [Google Scholar]

- Heavy metals and other elements in serum of cattle from organic and conventional farms. Biol. Trace Elem. Res.. 2011;143(2):863-870.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- European Union (EU). 2002. Heavy Metals in Wastes, European Commission on Environment. http://ec.europa.eu/environment/waste/studies/pdf/heavy_metalsreport.pdf.

- United State Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA). 2002. Biosolids applied to land: Advancing standards and practices. National Research Council, National Academy Press, Washinton. DC. 282.

- The assessment of cadmium, chromium, copper, and nickel tolerance and bioaccumulation by shrub plant Tetraena qataranse. Sci. Rep.. 2019;9(1):1-11.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Foliar spray with sodium hydrosulfide and calcium chloride advances dynamic of critical elements and efficiency of nitrogen metabolism in Cucurbita pepo L. under nickel stress. Sci. Hortic.. 2021;283:110052.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Physiological and molecular bases of the nickel toxicity responses in tomato. Stress Biol.. 2024;4(1):1-17.

- [Google Scholar]