Translate this page into:

Antibacterial Efficacy of AgNPs synthesized from Aloe vera extract and Staphylococcus aureus Culture Supernatant

⁎Corresponding author. kalarjani@ksu.edu.sa (Khaloud Mohammed Alarjani)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Biological synthesis of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) is an emerging method that avoids the need for costly equipment and hazardous chemicals. Therefore, in this study, Aloe vera (AV) extract and culture supernatant of Staphylococcus aureus (CS-S. aureus) were used to reduce and stabilise silver nanoparticles. The NPs were characterized using UV–vis spectrophotometry at 445 nm for AV-AgNP and 444.5 nm for CS-S.aureus AgNP, and the presence of silver was confirmed by energy dispersive X-ray (EDX). Furthermore, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) revealed that the AV-CS of S. aureus-AgNPs had irregular and spherical shapes, with average sizes of 18.5 nm for AvAgNPs and 7.03 nm for CS-S. aureus-AgNPs. Additionally, the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of both AgNPs showed a similar reaction. K. pneumoniae, P. aeruginosa, and S. epidermidis were more sensitive to the AgNPs compared to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). In conclusion, our study used a green method to synthesise silver nanoparticles using AV extract and CS of S. aureus. The NPs showed a remarkable antibacterial effect, especially CS-S. aureus-AgNP, which could have application as a treatment against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria.

Keywords

Staphylococcus aureus

Aloe vera extract

Cell-free supernatant

AgNPs

AvNPs

Antibacterial activity

1 Introduction

The problem of human pathogens that are resistant to antibiotics is a major concern and a health issue; there is a pressing need for a solution (Anandaradje et al., 2020). The problem of resistance has emerged due to inappropriate use of commercial antimicrobial drugs for treating infectious diseases (Salayová et al., 2021). These resistance mechanisms emerge in bacteria are due to several enzymatic and genetic mutations (Singh et al., 2018; Deljou and Goudarzi, 2016). This situation has forced scientists to look for new antimicrobial therapeutic drugs from different bio-sources, such as medicinal plants and microorganisms, which have been proven to be the best sources (Arbab et al., 2021). Therefore, it is essential to develop novel biological nanomedicine (Radulescu et al., 2023). Nanotechnology is the manufacturing of material at the nanoscale level. It is a rapidly growing platform, as it has applications in science and technology (Singh et al., 2018). Nanoparticles (NPs) are distinguished by their small size (1–100 nm), their unique properties, large surface areas, increased reactivity and ability to enter the human body easily (Huq, 2020). In addition, they have applications in multiple fields such as medicine, deliver of drugs and genes, cosmetics, electronics, biosensors and environmental remediation (R. El Shanshoury et al., 2020). Though there are many types of metal nanoparticles, silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) are of particular interest due to their distinct features, such as chemical stability, catalytic activity and optical behaviour (Al Zoubi et al., 2024). They also exhibit broad-spectrum bactericidal and fungicidal activity (Jadoun et al., 2021). Various techniques of synthesising nanoparticles, such as chemical and physical methods, have been documented as being expensive and consisting of hazardous and toxic substances, like stabilisers that are potentially harmful to the environment and biological systems (Radulescu et al., 2023). Hence, an alternative eco-friendly and safe synthesis method was required, which led to the green synthesis of nanoparticles using plants, microorganisms including fungi, yeast, algae and bacteria (Xu et al., 2020). The biological synthesis of AgNPs is considered to be an effective solution, because it is unlikely that pathogens are able to develop resistance against nano-silver without developing a broad range of mutations simultaneously in order to protect themselves (Singh et al., 2018). Using microorganisms to safeguard the environment is an appropriate method. (Saeed et al., 2020). They are also a rich source of bioactive chemicals that are crucial for the manufacture of nanomedicines (Singh et al., 2020). Plant-mediated synthesis of AgNPs has several advantages since it is quick, repeatable and ecologically sound. It is also economical and easy to apply on an industrial scale (Rónavári et al., 2021). Moreover, plants have intricate structures that can be employed to stabilise and produce nanoparticles. Plant parts, such as leaves, fruits, stems, seeds and roots, can all be used to make metal nanoparticles (Vanlalveni et al., 2021). Extracts of Lavandula angustifolia and Origanum vulgare have been used to synthesise AgNPs (Mustapha et al., 2022). Some plant’s phyto-constituents, specifically polyphenols, proteins and organic acids, may serve as reducing and capping agents for the surface of nanoparticles (Arshad et al., 2022).Fig S1.

In this study, two distinct biological methods, which are Staphylococcus aureus cell-free culture supernatant and AV plant extract, were used to synthesise silver nanoparticles. Then the antibacterial efficacy against pathogenic bacteria of the nanoparticles generated by these approaches was investigated.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Collection of experimental materials

AR-grade silver nitrate, AgNO3 (Sigma-Aldrich Chemicals, USA) and Aloe vera plant extract were used as the starting materials. Fresh Aloe vera (AV) plant was purchased from a local market in Riyadh. Mueller-Hinton agar (MHA) and Mueller-Hinton broth (MHB), sterilised distilled water and chloramphenicol (50 μg) were used. Meanwhile, bacterial strains including Gram-positive Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) [ATCC 29213], MRSA [ATCC 43300], Staphylococcus epidermidis (S. epidermidis) [ATCC 12228], and Gram-negative Klebsiella pneumoniae (K. pneumoniae) [ATCC 700603], Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa) [ATCC 27853] were obtained from the King Khalid University Hospital in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

2.2 Preparing the plant extract

The chopped AV leaves were boiled in 100 ml of sterilised distilled water for 15 min and allowed to cool overnight. The AV extract was filtered then stored at 4℃.

2.3 Preparing the cell- free culture supernatant (CFCS)

S. aureus was cultivated on MHA plates and incubated for 24 h at 37℃ then subcultured in MHB medium under the same previous incubation conditions. The culture was then centrifuged for 10 to 15 min at 8000 rpm, after which the supernatant was harvested and the pellet discarded. CS-S.aureus was preserved at 4℃.

2.4 Chemical composition assessment using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC/MS)

2.4.1 GC –MS analysis of AV extract

To analyse the AV extract, the leaf broth was air dried then the residue was dissolved in ethanol and then subjected to GC–MS analysis (Agilent Technologies 7890B Gas Detector, Santa Clara, CA, USA). These settings were used for a full scan of the sample (Research Center, Princess Noura University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia).

2.4.2 GC −MS analysis of CS-S. Aureus

To analyse the CS-S. aureus by GC–MS, the recovered supernatant was evaporated then the dried residue was dissolved in methanol, before being subjected to GC–MS. The GC–MS analysis conditions were the same as those used for the Av extract.

2.5 Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles

2.5.1 Using AV extract

Mixture of AV extract and AgNO3 solutions were placed in the sunlight and mixed continuously until a colour change was observed; it was then covered to prevent any oxidation.

2.5.2 Using CFCS of S. Aureus

20 Ml of AgNO3 (4 mM of AgNO3 in 50 ml of sterilised distilled water) was mixed with 10 ml of CFCS of S.aureus (pH:6.7and left in sunlight and mixed continuously until a colour change observed

2.6 Characterisation of silver nanoparticles

The AgNPs biosynthesised with Av extract and CS- S. aureus were characterised.

2.6.1 Uv–visible spectrophotometer

The UV–visible spectrophotometer (UV-1800, Shimadzu) was used to measure the absorption peaks of the AV extract and CS-S. aureus containing reduced silver ions. The spectra were recorded at (200–900 nm).

2.6.2 Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR)

The functional groups in charge of stabilising and capping AgNPs are shown by FT-IR spectrum analyses. With a resolution of 4 cm−1, the spectra were captured using FT-IR (IR Prestige-21 – Shimadzu) within 400–4000 cm−1 range.

2.6.3 Energy dispersive X-ray (EDX) analysis

The elemental investigation of the sample was carried out using EDX. It was recorded using a scanning electron microscope coupled with EDX (JSM-6380 LA).

2.6.4 Scanning electron microscope (SEM)

The shape and size of the AgNPs were observed using SEM. SEM was also used to examine the damage to the bacterial cell caused by the synthesised AgNPs. The images were captured using SEM (JSM-6380 LA) and field emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM-JSM 7610F-Japan) at different magnifications for detailed analysis. (Electron Microscope Unit, Central laboratory, Science College, King Saud University − Central Research Laboratory, Female Campus, King Saud University).

2.6.5 Transmission electron microscope (TEM)

TEM (JEOL-JEM-1011) was used to characterise the internal morphology and crystallographic data. (Electron Microscope Unit, Central laboratory, Science College, King Saud University).

2.7 Minimum inhibitory and bactericidal concentration (MIC − MBC) assessment

The Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute's standard broth dilution method (CLSI M07-A11) used to assess the antibacterial potential of the silver nanoparticles (Weinstein et al., 2018). Using an adjusted bacterial concentration (0.5 McFarland's standard) with Ag-NPs serial two-fold dilution at concentrations ranging from 500 μg/ml to 3.906µg/ml, the MIC was performed in MHB.

2.8 Determining antibacterial efficacy of nanoparticles using well-diffusion assay

The antibacterial activity testing was carried out by using an agar well-diffusion assay according to CLSI M02-A12 (Patel et al., 2015).

2.9 Statistical analysis

The data presented in the figures and tables in this study are values from triplicate experiments (± SD). To identify significant differences, One-Way-Analysis of variance (ANOVA) (p ≤ 0.05) was conducted using Origin 2024.

3 Results and Discussion

This study compared the antibacterial effectiveness of AgNPs manufactured using AV extract and CS-S. aureus against drug-resistant bacteria. The initial substance and the resultant mixtures were identified through the use of GC–MS, UV–vis spectrophotometry, FT-IR, EDX, SEM and TEM. Also, FE-SEM was used to visualise bacterial cell damage. To establish antibacterial susceptibility, the MIC, MBC and well agar diffusion techniques were employed.

3.1 Chemical composition assessment using GC–MS

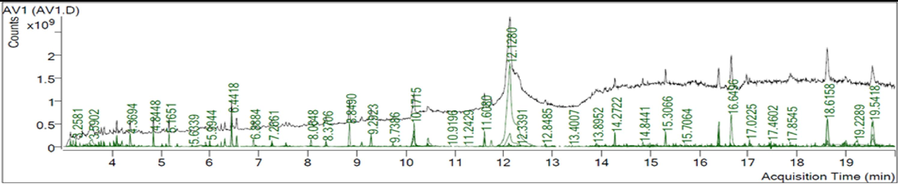

3.1.1 GC −MS analysis of AV extract

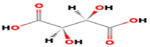

GC–MS analysis identified twenty- three active phytochemical compounds in the AV extract Table 1 lists several of the active compounds discovered. GC–MS analysis showed a variety of organic acids. Some of these organic acids such as oleic acid, 16-octadecenoic acid, phthalic acid and benzoic acid, which are known to possess antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial capabilities (Ngurah et al., 2020; Zahara et al., 2022).

RT (min)

Compound Name

Formula

Area

Structure

3.5515

(R,R)-Tartaric acid

C4H6O6

117,674,363

5.9207

Benzoic acid, 3,5-dihydroxy

C7H6O4

33,331,645

8.5507

Phthalic acid, butyl cyclobutyl ester

C19H26O4

8,455,539

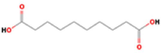

10.4565

Decanedioic acid

C10H18O4

926,532,760

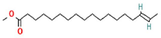

11.6080

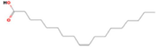

16-Octadecenoic acid, methyl ester

C19H36O2

507,171,941

12.1280

Oleic Acid

C18H34O2

17,259,234,829

15.7064

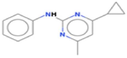

Cyprodinil

C14H15N3

32,768,685

16.0453

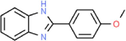

2-(4-Methoxy-phenyl)-1H-benzoimidazole

C14H12N2O

32,194,148

17.0225

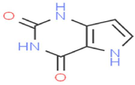

Pyrolo[3,2-d]pyrimidin-2,4(1H,3H)-dione

C6H5N3O2

236,483,815

17.8593

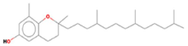

δ-Tocopherol

C27H46O2

85,691,761

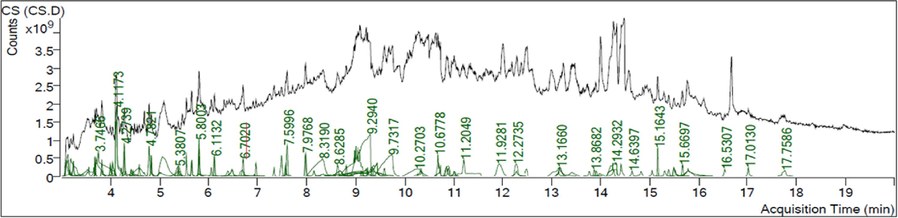

3.1.2 CS-S. Aureus GC −MS

Few studies investigated the components of CS-S. aureus and none of them match our results presented in Table 2. Twenty- five chemical compounds of CS-S. aureus were determined by GC–MS analysis. Table 2 displays a selection of the chemical compounds that were detected. Most of them, including 1H-indazole, 2,3-dihydro-1H-pyrrolo[1,2-a]benzimidazole, quinazoline and 4-dimethylamino-2(5H)-furanone, possess a significant antimicrobial, antitumor and anti-inflammatory activity (Alagarsamy et al., 2018; Siwach and Verma, 2021; Sulaiman et al., 2023).

RT (min)

Compound Name

Formula

Area

Structure

3.2368

Piperidine

C5H11N

733,754,457

3.7466

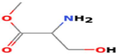

Serine, methyl ester

C4H9NO3

6,954,140,744

4.8249

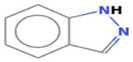

1H-Indazole

C7H6N2

493,740,511

5.8003

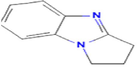

2,3-dihydro-1H-pyrrolo[1,2-a]benzimidazole

C10H10N2

1,311,393,575

5.8009

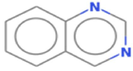

Quinazoline

C8H6N2

700,040,100

7.5675

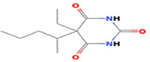

Pentobarbital

C11H18N2O3

555,198,321

8.3190

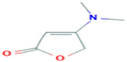

4-Dimethylamino-2(5H)-furanone

C6H9NO2

6,646,490,736

14.2652

2-Phenyl-3-methyl-pyrrolo(2,3-b) pyrazine

C13H11N3

428,223,218

14.2932

Naphyrone

C19H23NO

2,741,401,772

16.5307

Benzalphthalide

C15H10O2

367,395,119

3.2 Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles

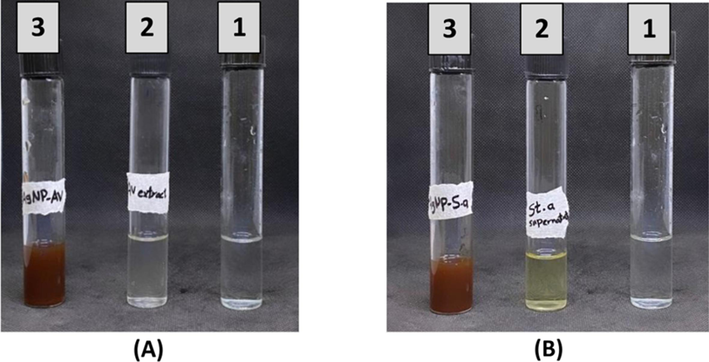

The Av extract and CS-S. aureus were used for AgNP synthesis since they possess a broad range of metabolites that may help in the reduction of AgNPs. The colour change of reaction mixtures from colourless or pale yellow to dark brown (Fig. 1) was indicated by visual observation.Fig. 2..

Production of AgNPs-AV (A3) and AgNPs-CS of S. aureus (B3). A1 and A2 were AgNO3 and Av extract, while B1 and B2 were AgNO3 and CS of S. aureus.

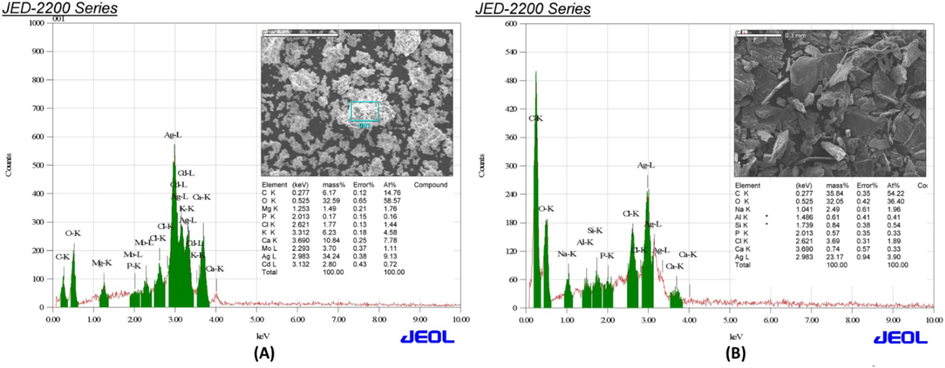

EDX images of synthesised AvAgNPs (A) and CS of S. aureus-AgNPs (B).

3.3 Silver nanoparticles characterisation

3.3.1 Uv–vis spectrophotometer examination

Figure S1: UV–vis spectrophotometry results of the synthesised AvAgNPs at 445 nm (A) and CS- S. aureus-AgNPs at 444.5 nm (B) at different time intervals (0 h, 24 h, 48 h and 72 h) at room temperature.

3.3.2 FT-IR results

The study used FT-IR to identify functional groups involved in the bio-reduction of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) by AV extract and their roles in stabilization. The spectrum of AV extract revealed peaks indicating the presence of alcohols, alkanes, amines, and phenols, confirming its capability as a reducing agent for AgNPs synthesis. After AgNPs formation, shifts in the peaks suggested the formation of a capping layer to prevent agglomeration. Additionally, FT-IR analysis of CS-S. aureus showed the presence of various biomolecules, which are essential for stabilizing AgNPs and reducing metal salts (Figure S2).

3.3.3 EDX findings

The EDX spectrum of AvAgNPs and CS-S. aureus-AgNPs shows a strong peak at 3 keV, indicating the presence of silver. AvAgNPs contain magnesium, phosphorus, chlorine, potassium, calcium, molybdenum, and cadmium, while CS-S. aureus-AgNPs include aluminum, sodium, chlorine, silicon, calcium, and phosphorus. These elements are believed to originate from the AV extract and CS-S. aureus used in the synthesis. Previous studies by Ansar et al. (2020) and Desai et al. (2020) also noted that these non-silver elements likely served as capping agents in biogenic synthesis.

3.3.4 SEM and TEM results

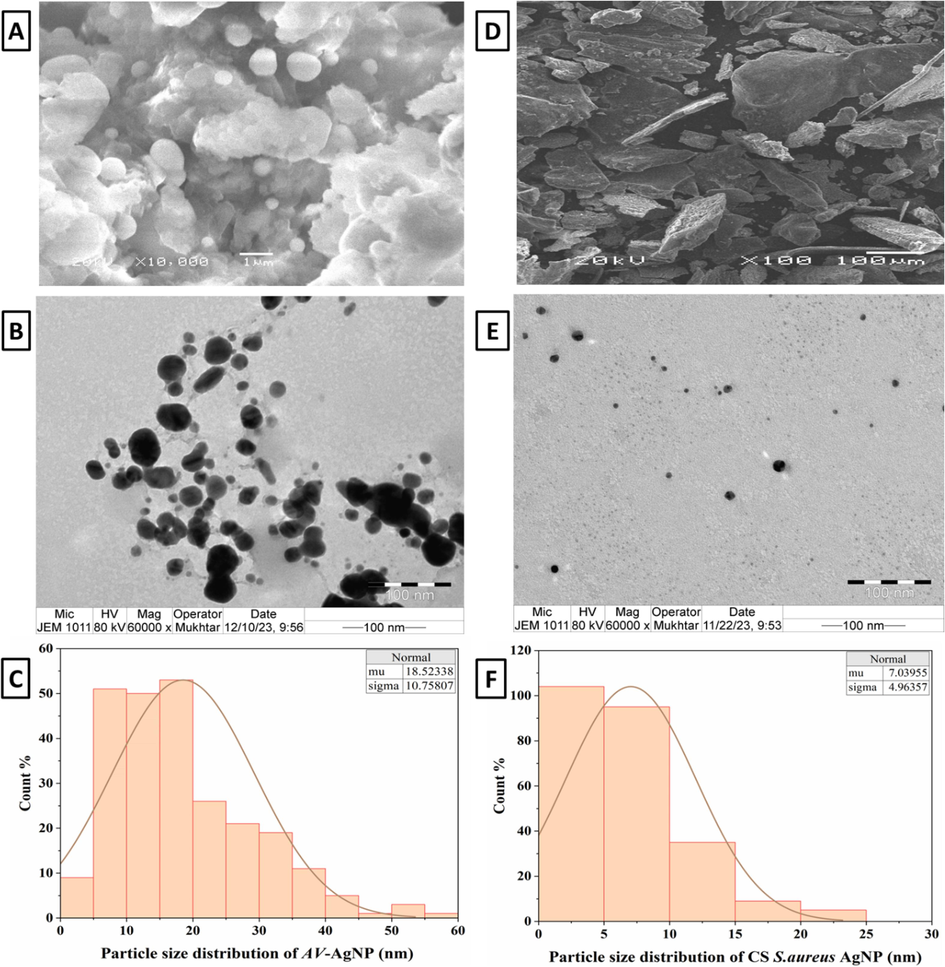

SEM and TEM were performed to examine the size and the nanostructure of the AgNPs. Images of AvAgNPs appear as spherical in shape and ranging in size from 3.1 to 59.2 nm (Fig. 3A and B). Meanwhile, CS of S. aureus-AgNPs was in the range of 1.2–23.4 nm and was spherical to irregular (Fig. 3D and E). Therefore, CS of S. aureus-AgNPs has a special size range compared with AvAgNPs. The histograms (Fig. 3C and F) show the average of 200 particles calculated using (Image J software incorporated with Origin software). It presents the average size of AV-AgNPs to be 18.5 nm, while the average size of CS of S. aureus-AgNPs was 7.03 nm.

SEM and TEM images of synthesised AvAgNPs (A and B) and CS of S. aureus-AgNPs (D and E), histograms of the particle size distribution (C and F).

3.4 MIC and MBC assessment

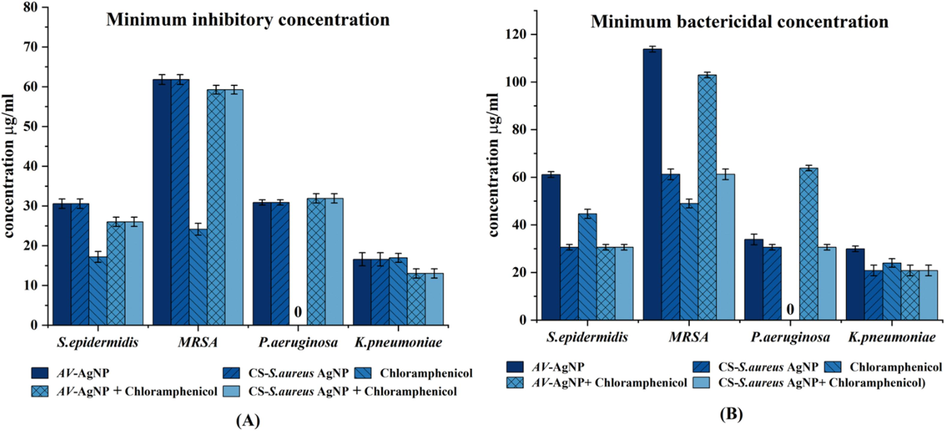

Since the MIC is the lowest amount of antibacterial substance that inhibits microbial growth, the tube's visual turbidity used as a marker for the MIC. It was observed that both types of AgNPs exhibited the same MIC activity. The highest sensitivity was for K. pneumoniae (15.625 µg/ml followed by P. aeruginosa and S. epidermidis. MRSA showed the lowest sensitivity at 62.5 µg/ml (Fig. 4A). The MIC test was also performed using chloramphenicol (50

g/ml). The findings indicated that P. aeruginosa was resistant, while MRSA had MIC of 25

g/ml. K. pneumoniae and S. epidermidis were highly sensitive, each with a MIC of 12.5 µg/ml. In addition, chloramphenicol was tested synergically with both types of AgNPs; the results are shown in Fig. 4A.

(A) MIC and (B) MBC values of synthesised AV-AgNPs, CS of S. aureus-AgNPs and chloramphenicol (in µg/ml). The values expressed are the mean of triplicate experiments (± SD) and carried out using one-way ANOVA (p ≤ 0.05).

Fig. 4B shows the MBC values for the tested bacteria; however, the interesting point is that the MBC values for AgNPs vary. The MBC for K. pneumoniae was 15.625 g/ml for CS-S. aureusAgNPs, while for AvAgNPs, it was 31.25 g/ml. This was followed by P. aeruginosa, S. epidermidis and lastly MRSA = 62.5 g/ml, 125 g/ml. Farouk et al. (2020) has reported that S. aureus was the most resistant with low MIC, MBC to AgNPs than Gram-negative S. typhi.

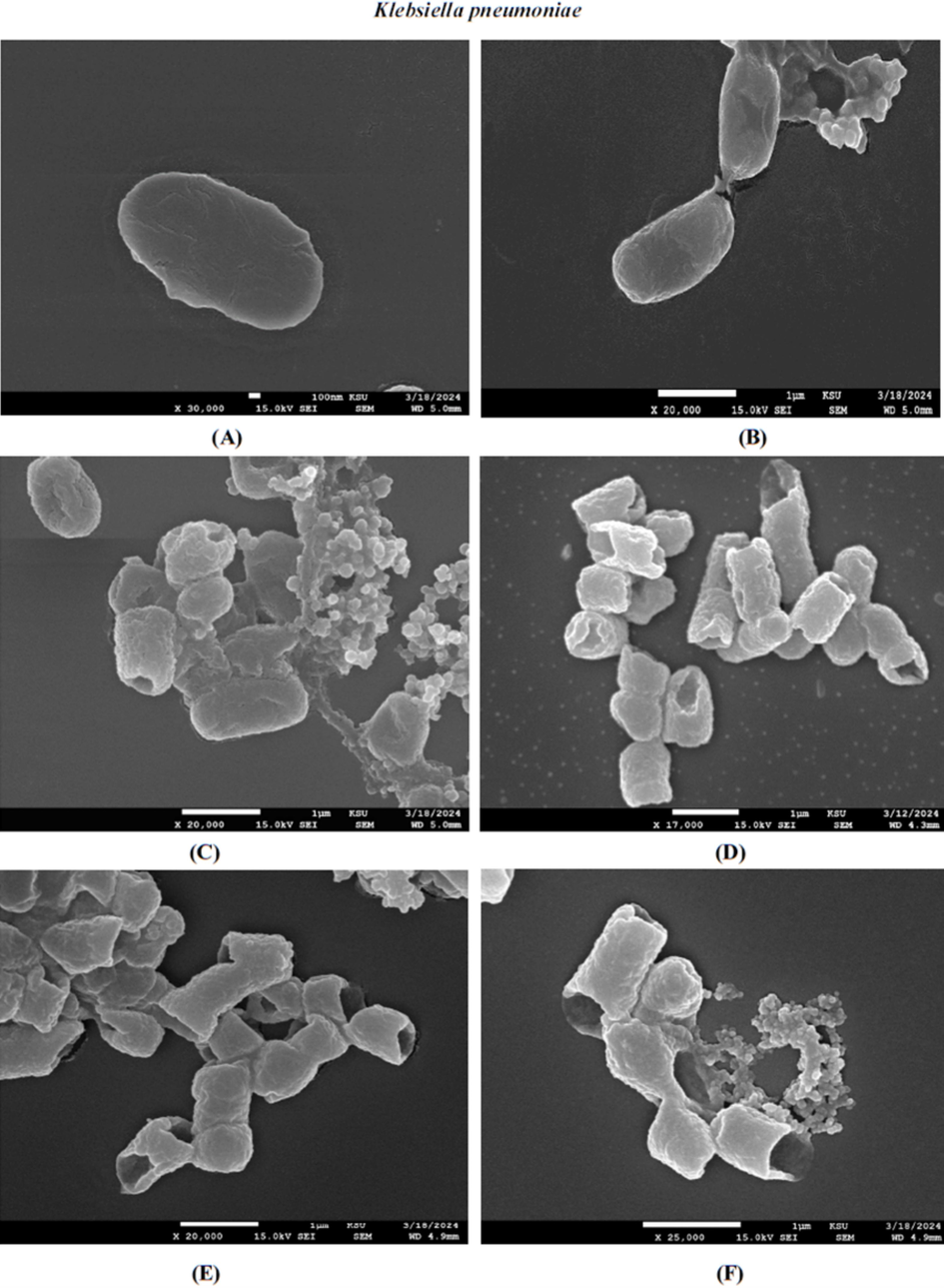

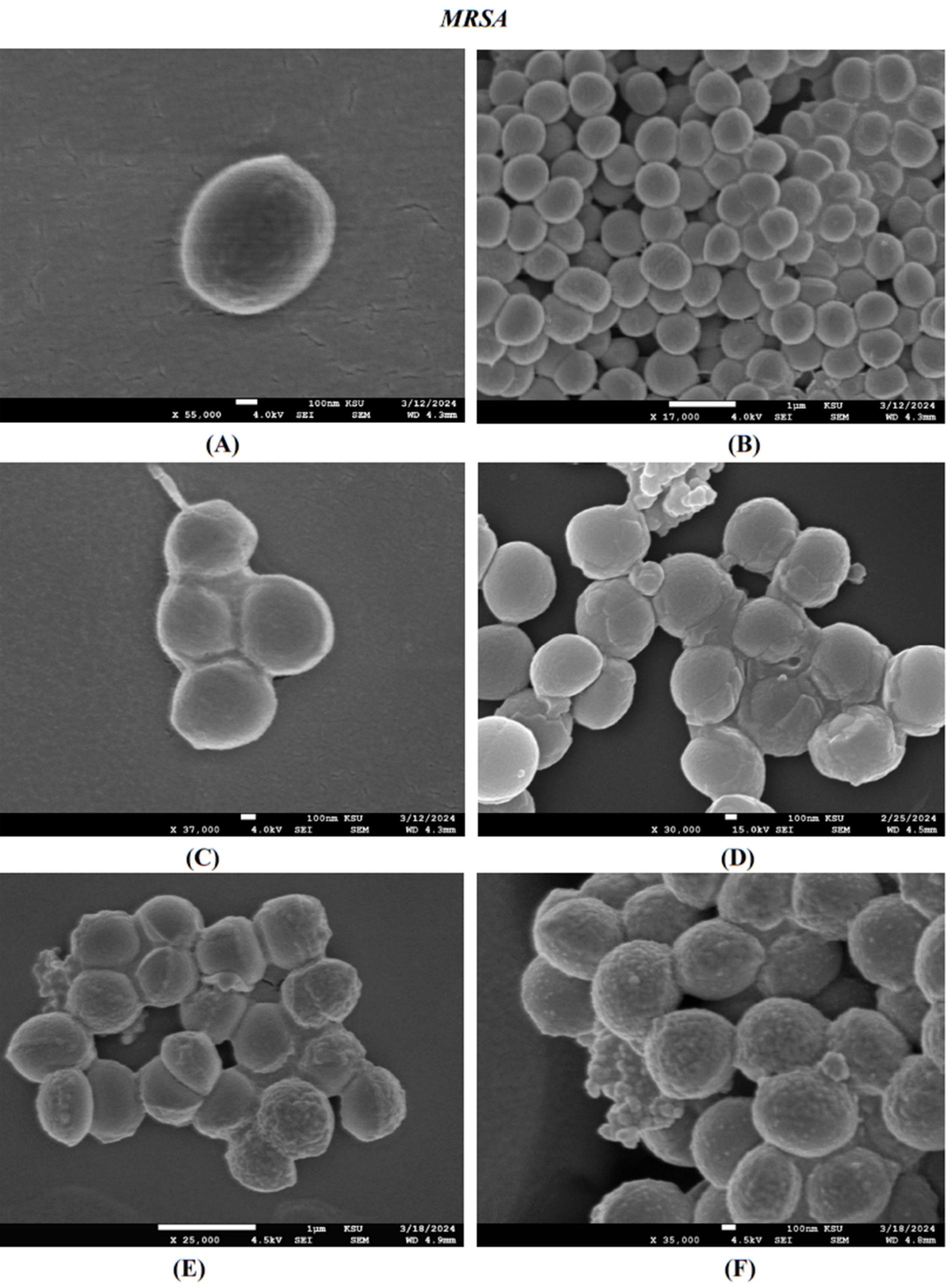

3.5 Cell damage screening using FE-SEM

We used FE-SEM to assess the surface morphological changes caused by the AgNPs and chloramphenicol on K. pneumoniae; and the changes were compared to untreated bacteria. The tested samples were taken at their MIC concentrations and K. pneumoniae considered as the most sensitive due to MIC results. Fig. 5C and D show the damage to the cell after exposure to AvAgNPs and CS-S. aureus-AgNPs. Treatment led to cellular changes, with clear signs of deformation, shrinkage and fracture. In addition, the walls of K. pneumoniae ruptured, causing intracellular components to leak out, which could be observed surrounding the cell, leading to cell death, especially when treated with CS-S. aureus-AgNPs (Fig. 5D). These NPs have a greater bactericidal effect than AvAgNPs, in which some intact cells were observed (Fig. 5C). Further investigation was conducted to determine the MIC of chloramphenicol + CS-S. aureus-AgNPs; a synergic effect was observed. Fig. 5F reveals the K. pneumoniae cells were severely damaged. Whereas Fig. 5A and B presents the untreated cells as having intact cell wall and being within a normal size range.

FE-SEM images of the resulting effect upon K. pneumoniae of untreated (A and B), synthesised AvAgNPs (C), CS of S. aureus-AgNPs (D), chloramphenicol (E), chloramphenicol with CS of S. aureus-AgNPs (F).

According to the MIC results, MRSA was the most resistant bacteria. Fig. 6A and B show the untreated cells have a smooth surface and intact cell wall. In contrast, Fig. 6C and D show a misshapen cell wall after being treated with AvAgNPs and CS-S. aureus-AgNPs. A greater effect was observed in with CS-S. aureus-AgNPs, where there was clear surface damage and minor internal leakage. Additionally, chloramphenicol was scanned both separately and with CS-S. aureus-AgNPs (Fig. 6E and F).

FE-SEM images of the resulting effect upon MRSA of untreated (A and B), synthesised AvAgNPs (C), CS of S. aureus-AgNPs (D), chloramphenicol (E), chloramphenicol with CS of S. aureus-AgNPs (F).

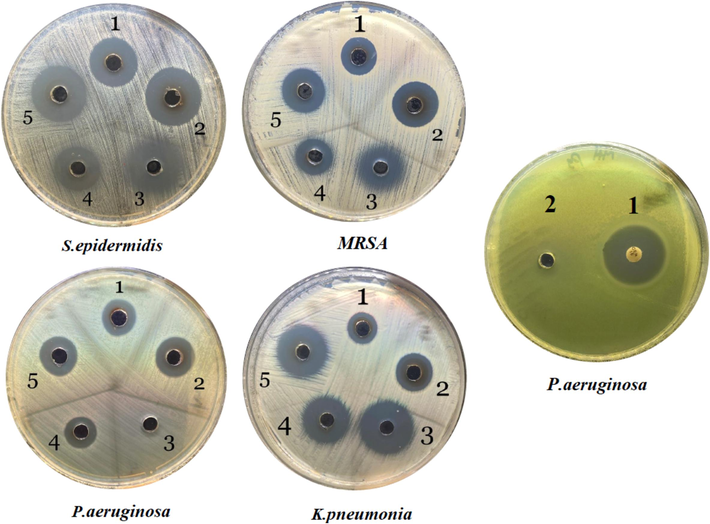

3.6 Assessment of the antibacterial activity of the synthesised silver nanoparticles using a well-diffusion assay

Our results showed that AvAgNPs and CS-S. aureus-AgNPs have different antibacterial activity against all the tested bacteria (Fig. 7). The presence of an inhibition zone allowed for the quantitative evaluation of antibacterial activity. MRSA showed a large diameter of inhibition zone (DIZ) (18.6

0.6 mm) for CS-S. aureus-AgNP and (14.3

mm) for AV-AgNP. However, S.epidermidis had the largest DIZ (22.3

0.6 mm) and (18.3

0.6 mm) (Table 3). According to Al Mutairi et al. (2022), who manufactured AgNPs and evaluated them against some drug-resistant bacteria found that it had an impressive antibacterial capacity specifically against S. aureus.

Zone of inhibition (mm)

Tested bacteria

AV-AgNP (well 1)

CS-S.aureus- AgNP

(well 2)Chloramphenicol (50 µg)

(well 3)

AV-AgNP + Chloramphenicol

(well 4)CS-S.aureus- AgNP + chloramphenicol

(well 5)

Methicillin-

resistant Staphylococcus aureus

14.3

18.6

0.6

19.5

0.5

15.1

0.2

18.2

0.5

Staphylococcus epidermidis

18.3

0.6

22.3

0.6

19.8

0.3

18.1

0.4

21.8

0.3

Klebsiella pneumoniae

13.2

0.3

15

0.2

22.1

0.3

20.3

0.3

21.2

0.3

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

13.1

0.4

15.1

0.2

0

13.1

0.1

15

0.5

Moreover, AgNPs were evaluated in combination with chloramphenicol, it emerged that the combination was not potent against all bacteria, only K. pneumoniae. However, when chloramphenicol was tested individually, it exhibited moderate antibacterial activity against all bacteria, except P. aeruginosa, in which it was found to be resistant. To confirm its resistance, a gentamicin disc was tested only on P. aeruginosa (Fig. 7), which demonstrated that it was susceptible to it. Other investigations reported by Lorusso et al. (2022) have demonstrated that P. aeruginosa has a remarkably low susceptibility to antibiotics.

The antibacterial effect upon different bacterial strains treated with AV-AgNP (1), CS of S. aureus-AgNP (2), chloramphenicol (3), AV-AgNP + chloramphenicol (4), CS of S. aureus-AgNP + chloramphenicol (5).

Some factors affecting the antibacterial activity of AgNPs such as, size, shape, surface modification and the techniques applied for synthesis (Nie et al., 2023).

Yousaf et al. (2020) revealed that the size of NPs has a significant impact upon their antibacterial efficacy. Smaller size particles have shown stronger antibacterial activity, reflecting that they have greater capability to enter into bacteria. The smaller size NPs have a larger surface area than bigger NPs, resulting in higher antibacterial activity. That study agrees with our results, which found that the nanoparticle size generated by CS − S. aureus was smaller than the size produced by AV and the former exhibited greater antibacterial activity against bacteria in our tests.

4 Conclusion

Our study successfully produced silver nanoparticle using AV extract and CS of S.aureus, which are known as a green, eco-friendly and biological substances. The synthesised AgNPs showed a noticeable effect as an antibacterial agent against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Further investigations will assure that AgNPs of AV extracts and CS of S. aureus are applicable as treatments for bacterial infections.

Funding

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deputyship for Research & Innovation, Ministry of Education in Saudi Arabia for funding this research work through the project no. (IFKSUDR_H260).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Asma Ahmed Al-mehdhar: . Khaloud Mohammed Alarjani: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Noura Salem Aldosari: . Mai Ahmed Alghamdi: Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft.

Acknowledgment

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deputyship for Research & Innovation, Ministry of Education in Saudi Arabia for funding this research work through the project no. (IFKSUDR_H260).

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Antimicrobial Activity of Green Silver Nanoparticles Synthesized by Different Extracts from the Leaves of Saudi Palm Tree (Phoenix Dactylifera L.) Molecules. 2022;27:3113.

- [Google Scholar]

- Green Nanofertilizers: the Need for Modern Agriculture, Intelligent, and Environmentally-Friendly Approaches. Ecol. Eng. Environ. Technol.. 2024;25:1-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- An overview of quinazolines: Pharmacological significance and recent developments. Eur. J. Med. Chem.. 2018;151:628-685.

- [Google Scholar]

- Microbial Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles and Their Biological Potential. In: Shukla A.K., ed. Nanoparticles in Medicine. Singapore: Springer; 2020. p. :99-133.

- [Google Scholar]

- Eco friendly silver nanoparticles synthesis by Brassica oleracea and its antibacterial, anticancer and antioxidant properties. Sci. Rep.. 2020;10:18564.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparative study of antimicrobial action of aloe vera and antibiotics against different bacterial isolates from skin infection. Vet. Med. Sci.. 2021;7:2061-2067.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis of Aloe vera-conjugated silver nanoparticles for use against multidrug-resistant microorganisms. Electron. J. Biotechnol.. 2022;55:55-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- Green Extracellular Synthesis of the Silver Nanoparticles Using Thermophilic Bacillus Sp. AZ1 and its Antimicrobial Activity Against Several Human Pathogenetic Bacteria. Iran. J. Biotechnol.. 2016;14:25-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- R. El Shanshoury, A.E., Z. Sabae, S., A. El Shouny, W., M. Abu Shady, A., M. Badr, H., 2020. Extracellular Biosynthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Aquatic Bacterial Isolate and its Antibacterial and Antioxidant Potentials. Egypt. J. Aquat. Biol. Fish. 24, 183–201.

- The Role of Silver Nanoparticles in a Treatment Approach for Multidrug-Resistant Salmonella Species Isolates. Int. J. Nanomedicine. 2020;15:6993-7011.

- [Google Scholar]

- Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Pseudoduganella eburnea MAHUQ-39 and Their Antimicrobial Mechanisms Investigation against Drug Resistant Human Pathogens. Int. J. Mol. Sci.. 2020;21:1510.

- [Google Scholar]

- Role of Efflux Pumps on Antimicrobial Resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Int. J. Mol. Sci.. 2022;23:15779.

- [Google Scholar]

- A Review on Plants and Microorganisms Mediated Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles, Role of Plants Metabolites and Applications. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 2022;19:674.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antibacterial evaluation of 2,4-dihidroxy benzoic acid on Escherichia coli and Vibrio alginolyticus. J. Phys. Conf. Ser.. 2020;1503:012027

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, applications, toxicity and toxicity mechanisms of silver nanoparticles: A review. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf.. 2023;253:114636

- [Google Scholar]

- Performance standards for antimicrobial disk susceptibility test; approved standards, 12 (ed. ed). Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2015.

- Green Synthesis of Metal and Metal Oxide Nanoparticles: A Review of the Principles and Biomedical Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci.. 2023;24:15397.

- [Google Scholar]

- Green Silver and Gold Nanoparticles: Biological Synthesis Approaches and Potentials for Biomedical Applications. Molecules. 2021;26:844.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bacterial-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their significant effect against pathogens. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res.. 2020;27:37347-37356.

- [Google Scholar]

- Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles with Antibacterial Activity Using Various Medicinal Plant Extracts: Morphology and Antibacterial Efficacy. Nanomaterials. 2021;11:1005.

- [Google Scholar]

- Singh, H., Du, J., Singh, P., Yi, T.H., 2018. Extracellular synthesis of silver nanoparticles by Pseudomonas sp. THG-LS1.4 and their antimicrobial application. J. Pharm. Anal., Advances in Pharmaceutical Analysis 2017 8, 258–264.

- Antimicrobial and Biofilm-Preventing Activity of l-Borneol Possessing 2(5H)-Furanone Derivative F131 against S. aureus—C. albicans Mixed Cultures. Pathogens. 2023;12:26.

- [Google Scholar]

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using plant extracts and their antimicrobial activities: a review of recent literature. RSC Adv.. 2021;11:2804-2837.

- [Google Scholar]

- Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically: M07–A11, 11 (edition. ed). Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2018.

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their applications as an alternative antibacterial and antioxidant agent. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 2020;112:110901

- [Google Scholar]

- In-vitro examination and isolation of antidiarrheal compounds using five bacterial strains from invasive species Bidens bipinnata L. Saudi J. Biol. Sci.. 2022;29:472-479.

- [Google Scholar]

Appendix A

Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2024.103464.

Appendix A

Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article: