Translate this page into:

In vitro and in silico evaluation of anti-quorum sensing activity of marine red seaweeds-Portieria hornemannii and Halymenia dilatata

⁎Corresponding author. nv12507@annamalaiuniversity.ac.in (Natesan Vijayakumar)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

The bacterial cell communicates from one cell to another by binding Auto-Inducers to specific receptors and their virulence factors, which are all products of their expression system. Therefore, this pathogenesis is controlled by disrupting the signal-response system. The current study assesses three maritime red seaweeds, including Portieria hornemannii and Halymenia dilatata, for their anti-Quorum Sensing (QS) activity against four bacteria. Those opportunistic pathogens cause severe QS-dependent biofilm formation and other virulences. In vitro, the study showed that biofilm formation in S. aureus was inhibited with 43.3%, 55% in Acinetobacter sp, 48% in E. coli, and 39. 2 % in K. pneumoniae by red seaweed extracts. The EPS production was also highly inhibited in Acinetobacter sp. with 41 % more than other bacteria. The efflux pump expressions and QS-dependent swimming motility were also effectively reduced. The present study targets the receptor proteins to prevent from binding of QS signals. Correspondingly, the in silico research predicts the binding affinity of bioactive compounds of seaweed extracts to the QS receptor proteins. The Hexamethyl Cyclotrisiloxane, Benzo[h]quinoline, 2,4-dimethyl, and 5-Methyl-2-phenylindolizine compounds from H. dilatata, P. hornemannii, respectively, showed a higher binding affinity with receptor proteins such as AgrC (PDB ID: 4BXI) of S. aureus, SdiA (PDB ID:4LFU) of E. coli, Modelled SdiA protein of K. pneumoniae and Modelled AbaR protein of Acinetobacter sp. This study demonstrates the potential of seaweed against virulence and antibiotic resistance of pathogenic bacteria.

Keywords

Quorum sensing

Antibiotic-resistant

Biofilm inhibition

Efflux pump

Protein modeling

Molecular docking

1 Introduction

Multiple drug resistance of pathogenic bacteria and their biofilms associated with QS are rapid arrivals. Developing antipathogenic and anti-QS agents is necessary to control this virulence (Haddadin et al., 2019). Bacteria use QS, a molecular communication mechanism that depends on cell density (Rashiya et al., 2021) that was first reported in marine bacteria; within a biofilm, bacteria have a much-increased chance of surviving in the face of famine, drought, and antibiotic use. Quorum quenching, which has garnered much interest, inhibits the collection of virulence factors previously stated. It may include the breakdown of signal molecules bacteria use to coordinate behavior within colonies. Additionally, leaf extraction and biofilms based on nanoparticles are crucial for biological applications (Talla et al., 2023; Tamfu et al., 2023; Tamfu et al., 2022; Ikome et al., 2023; Doğaç et al., 2023).

A membrane-bound inducer molecule and a kinase receptor comprise the two halves of the gram-positive QS system. The QS target gene transcription factor is phosphorylated and activated by the receptor kinase. The signaling molecules like 4-hydroxy-5-methyl-3(2H)-furanone, Auto inducing peptides (AIP), Gelatinase biosynthesis activating pheromone, γ-butyral lactone, PI, and M-factors from various species, respectively, are investigated—each gram-positive hydroxy four quinolone (PQS). The AgrD protein activates the membrane-bound AgrB and secretes AIPs that bind to AgrA. RNA III transcript was then started, altering gene expressions, including biofilm development and Virulence factor production (Huang et al., 2021).

LuxI/LuxR QS system is most common in gram-negative bacteria that use N-Acyl homoserine lactones as signaling molecules (Nguyen et al., 2015). A recent study revealed that SdiA, which is a homolog of LuxR, is used as a QS receptor by E. coli and K. pneumoniae (Wang et al., 1991).

QS-dependent biofilm formation has a multi-step cyclic process involving intra and inter-bacterial species communication. Extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) are vital in producing biofilms, which QS mediates. Efflux pumps are chromosomally encoded, increasing resistance to these specific mechanisms. QS also has a role in pathogenicity, biofilm formation, and antibiotic resistance.

The molecular communication should be interrupted to control Biofilm formation, Sporulation, Motility, and release of virulence from pathogenic bacteria, Pigmentation, and Bacteria-plant interactions. Three main mechanisms inhibited the QS. They are the inhibition of AIs synthase, Inactivation or enzymatic degradation of signaling molecules -Quorum quenching, and Blocking the signal receptor (Paluch et al., 2020).

The anti-biofilm and anti-QS action of marine red seaweed extracts is investigated in this study because of bio-active and unique structural chemicals in marine environment products. Klebsiella pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, and Acinetobacter sp., are used as test organism that forms pathogenic biofilms and resists some antibiotics. QS inhibiting compounds may apply in different fields like marine environments as anti-fouling agents, controlling biofilms in medical devices like catheters, ventilators, and Membrane Bioreactor (Piruthivraj et al., 2024). The repeated use of antibiotics may cause resistance in pathogenic bacteria and biofilms. Therefore, the novel QS-inhibiting compounds may block their communication without harming good bacteria.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Gathering of marine red seaweeds

Portieria hornemannii and Halymenia dilatata (100 g each of dried samples) were acquired from the RK Algae project center located in Mandapam, Ramanathapuram, Tamil Nadu, India, as illustrated in Supplementary Figure S1.

2.1.1 Authenticating marine red seaweeds

The red seaweeds are identified as Portieria hornemannii (Lyng.) P.C. Silva –Rhizophyllidaceae (BSI/SRC/5/23/2022/Tech/470) and Halymenia dilatata Zanardini– Halymeniaceae (BSI/SRC/5/23/2022/Tech/469). Dr. S.S. Hameed, The Scientist- E & Head of Office, Botanical Survey of India, TNAU Campus, Coimbatore, India, confirmed this identification of the red seaweed samples.

2.2 Extraction of red seaweeds

2.2.1 Methanol extraction

At room temperature, 15 g of dried algae were each ground up and soaked in 300 mL of methanol for three days on a rotating shaker that turned 75 times per minute. The mixtures that were made were filtered with Whatman No. 1 filter paper. When identical amounts of cold diethyl ether were added to the filtering liquid, protein residues began to form. At 80 °C, a rotating evaporator was used to remove the solvents. The dried extracts were using further process.

2.2.2 Aqueous extraction

Algal powder (20 g) was added to 100 mL of sterile distilled water, and the mixture was shaken at 140 rpm for two days while being kept at room temperature. Freeze-drying was performed in a Lyophilizer after filtering the slurry with Whatman no. 1 filter paper (Kulshreshtha et al., 2016).

2.2.3 Extraction yield

The extraction yield of Portieria hornemannii and Halymenia dilatata obtained from Methanolic and sterile distilled water extraction are shown in Table 1. The highest value was obtained in distilled water extraction than in methanolic extraction. These yields were calculated in percentage using the formula obtained from (Mansuya et al., 2010).

S.No

Red seaweeds withDry weight of seaweed powder

(g)Types of extracts [initial samples(g)]

Extracts yield

Extract yield in %

Aqueous

Methanol

Aqueous (g)

Methanol

(mg)Aqueous

Methanol

1

Halymenia dilatata −75.8

20

15

6

2300

30

18

2

Portieriachornemannii- 58

20

15

3.6

700

18

4.6

The collected samples are authenticated in the Botanical Survey of India, Coimbatore, India.

2.3 Strains of bacteria and conditions for culturing

The bacterial strains used in this study are Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 13883, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 1690, Escherichia coli ATCC 15224, and Acinetobacter sp. ATCC 49139. All bacterial cultures were sourced from Bishop Heber College, located in Trichy, India. Each bacterial strain underwent culturing at 37 °C for 24 h.

2.4 Antibacterial assay

The antibacterial activity was tested for all algal extracts against ATCC Bacterial Strains No. 15224, 1690, 49139, and 13883. In nutrient medium, the overnight culture of all test pathogens was inoculated. Following turbidity, the cultures were swabbed onto Muller–Hinton agar plates. The plates were then incubated at 30 °C for 24 h, after which a sterile disc containing 20 mg of algal extract was placed on top of each plate (Packiavathy et al., 2012).

2.5 Anti-Biofilm assay

The effects of algal extracts at different concentrations (20–100 mg/mL) on the biofilm formation by Klebsiella pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, and Acinetobacter sp. were studied in 96 Well plates. 2 percent of test organisms are inoculated with extracts in a fresh nutrient medium. As a control, the culture broth without extract was used. Planktonic cells were removed by washing the medium with phosphate-buffered saline after 24 h of incubation at 37 °C. The biofilms were stained with 100 μL of 0.1 % crystal violet for 10 min, followed by rinsing with distilled water to remove excess stain. Subsequently, 100 μL of 95 % ethanol was added to each well to dissolve the biofilm, and its quantification was performed using a microplate reader at 570 nm (Al-kafaween et al., 2019). The formula used to determine the percentage of biofilm inhibition was:

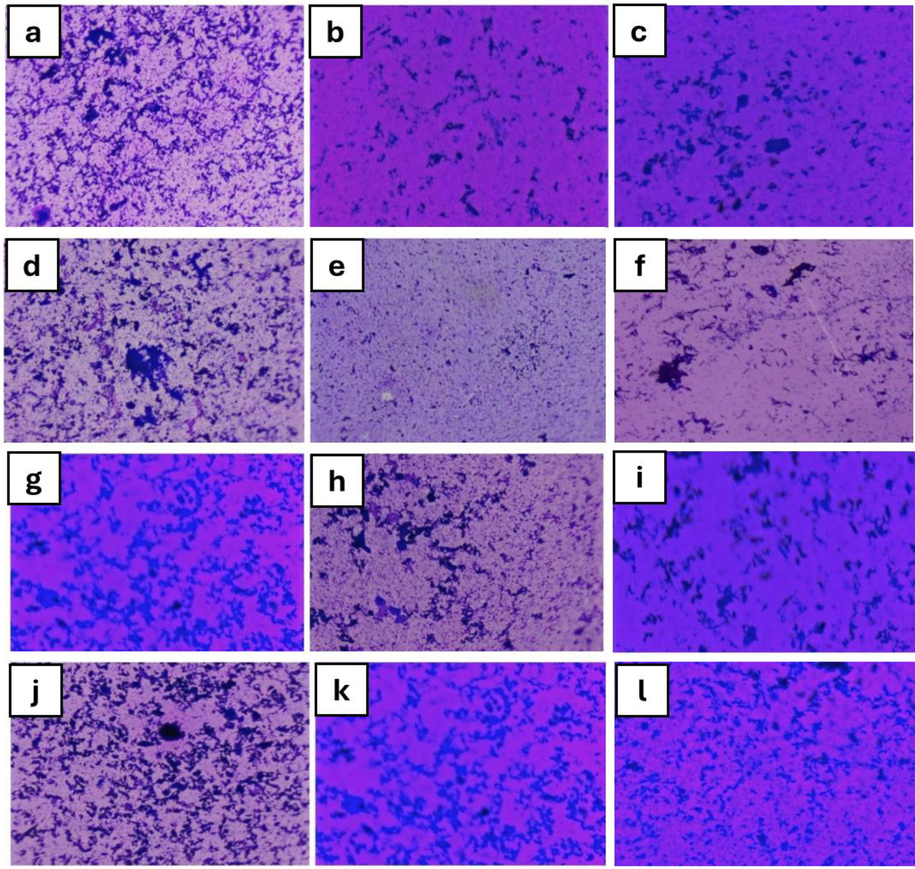

2.5.1 Light Microscopic analysis

1 % of overnight cultures of the test pathogens were inoculated into 3 mL of fresh nutrient medium containing cover glass along with and without algal extracts (50 mg/mL) and incubated for 24 h. After incubation, the cover glasses were rinsed with sterile distilled water to remove the planktonic cells, and 0.2 % CV was added. Stained cover glasses were placed on slides and visualized using a light microscope (Packiavathy et al., 2012).

2.5.2 Visualization of biofilm using tube method

Test tubes containing 5 mL of nutrient broth and 1 % glucose containing 25 mg of algal extracts were added with test microorganisms. Culture test tubes without extracts are maintained as a control. Crystal violet (0.1 %) was added after incubation at 37 °C for 24 h, and the tubes were rinsed with phosphate buffer saline. The extra stains were washed away with distilled water and dried (Freeman et al., 1989).

2.6 EPS extraction and quantification

In the presence and absence of methanolic extract of Halymenia dilatata and lyophilized extracts of Portieria hornemannii, with 100 mg/mL concentration, test pathogens ATCC Bacterial Strains No. 15224, 1690, 49139, and 13,883 were allowed for biofilm formation using cover slip in a 6-well microtiter plate (MTP) which was incubated at 37 °C for 18 h. One hour of dark incubation followed by cleaning with 0.9 % NaCl (0.5 mL), 5 % phenol (0.5 mL), and five volumes of concentrated H2SO4. Then, the absorbance at 490 nm was recorded on a UV–VIS spectrophotometer (Favre-Bonte et al., 2003). The percentage of EPS inhibition was calculated using the formula,

EPS inhibition percentage = [(Control OD- Test OD) / Control OD] × 100.

2.7 Swimming assay

A suitable medium was created by combining 1 % tryptone, 0.5 % NaCl, and 0.3 % agar with a 25 mg concentration of algal extracts. As a control, a swim plate without algal extract was used. In addition, test pathogens were grown in point-inoculated cultures in the middle of the medium overnight. For 18 h, the plates were incubated upright at 37 °C (Musthafa et al., 2012).

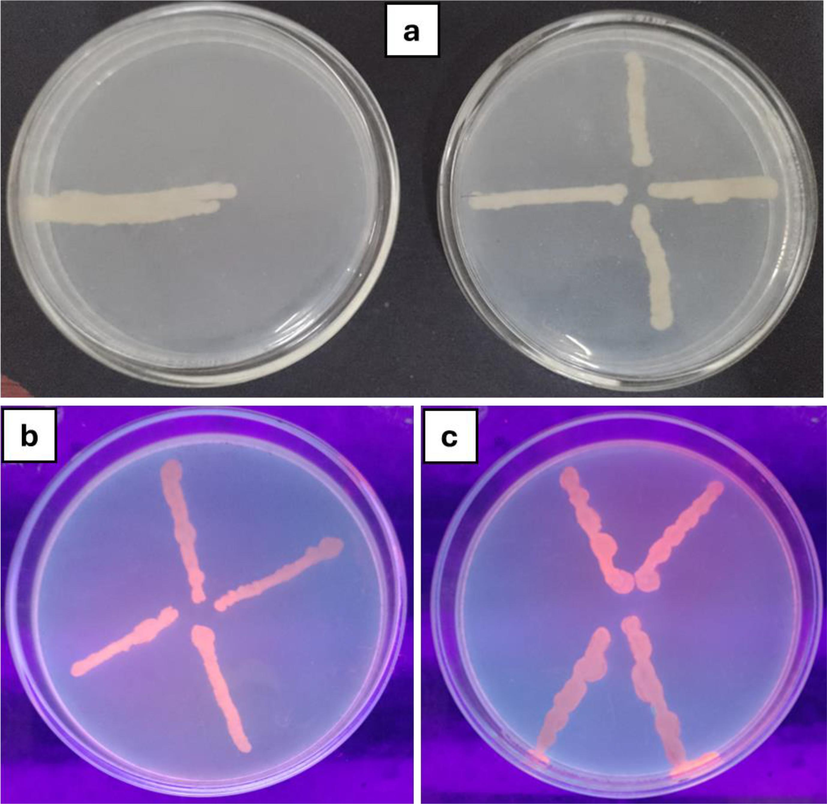

2.7.1 Ethidium Bromide-Agar cartwheel assay

The presence of efflux pumps was discovered with this test due to the accumulation of EtBr inside the cells, which causes enhanced fluorescence. Before culture, EtBr (2 mg/mL) and algal extracts (25 mg) were applied to MH agar plates. The bacterial cultures were then cartwheeled onto agar plates. Plates were incubated at 37 °C for 16 h before being examined with a UV transilluminator for EtBr accumulation (Eleftheriadou et al., 2021).

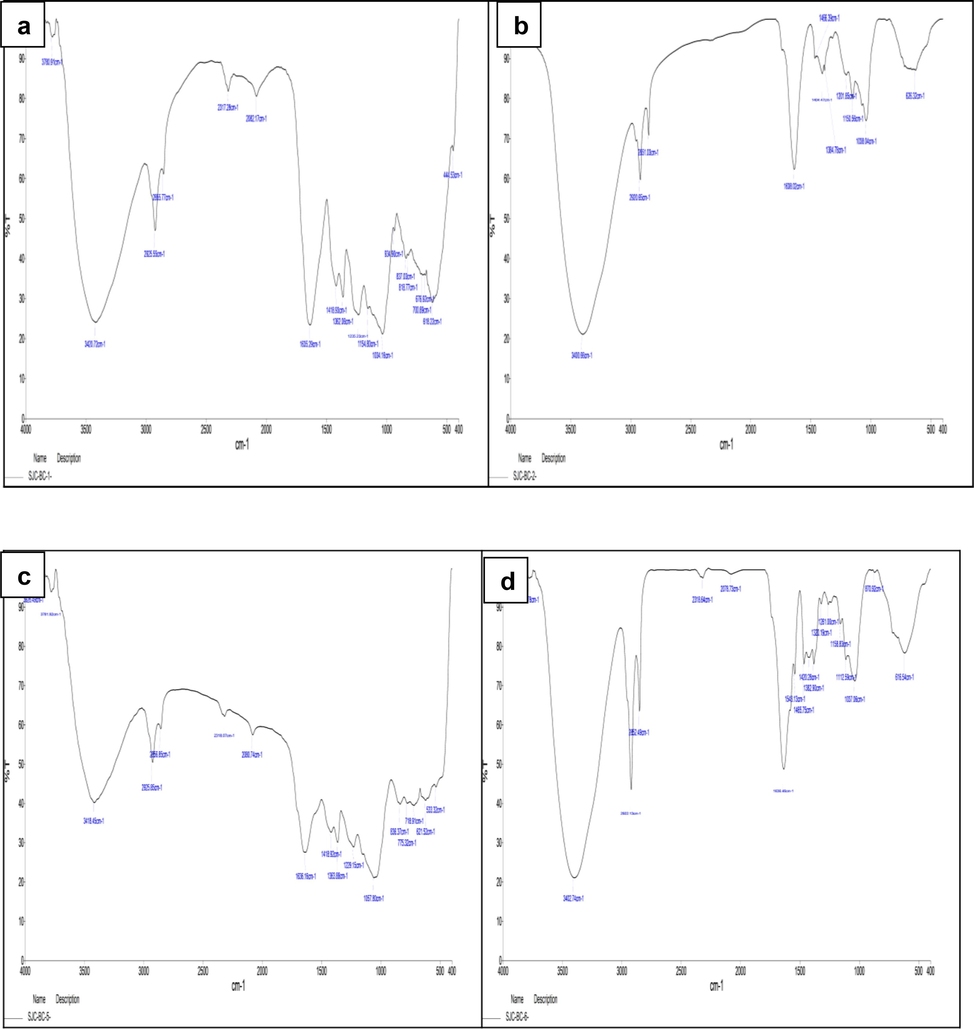

2.8 FTIR analysis

The methanolic and aqueous extract of Portieria hornemannii and Halymenia dilatata are analyzed by FTIR in St. Joseph College, Trichy. This parameter is used to identify the structure and functional groups of compounds present in extracts.

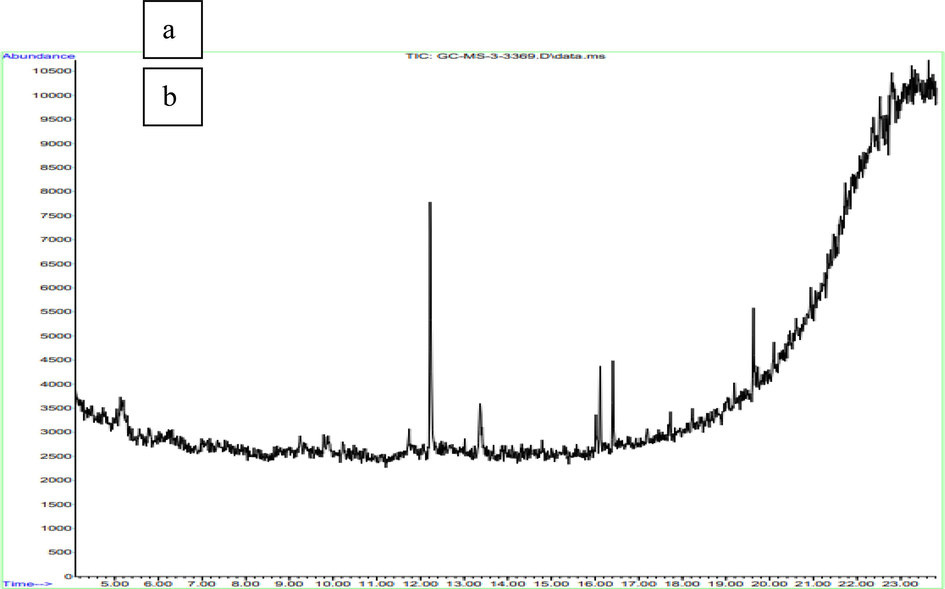

2.9 Recognition of compounds by GC − MS

GC–MS analysis was conducted on the methanolic extract of Halymenia dilatata and aqueous extracts of Portieria hornemannii at TUV SUD South Asia Pvt. Ltd, Tirupur, This analysis aimed to identify the bio-active compounds present in the algal extracts.

2.10 Evaluation of Anti-Qs activity through molecular docking Analysis

The ten compounds from Halymenia dilatate, and 15 compounds from Portieria hornemannii reported in GC–MS analysis. Based on high peak area and peak percentage, three compounds from Halymenia dilatate and two from Portieria hornemannii were selected separately as ligands for molecular docking analysis. The structure of these compounds is obtained from PubChem databases. Then, the QS receptor proteins, including SdiA (PDB ID: 4LFU) for ATCC strain NO. 15224 and 13883 (Kim et al., 2014). AgrC (PDB ID: 4BXI) and AbaR are selected for ATCC strain NO. 1690 and 49139 (Srivastava et al., 2014; Saleem et al., 2020) respectively. The SdiA of K. pneumoniae ATCC 13883 (Ahamad et al., 2020) and AbaR of Acinetobacter sp. ATCC 49139 was modeled for further docking studies to predict binding scores along with protein–ligand interactions (Singh et al., 2016).

2.10.1 UNIPROT

To access up-to-date, comprehensive, freely available, and central resources on protein sequences and functional annotation, visit the Universal Protein Resource (Uniprot) at https://www.uniprot.org. The SdiA of K. pneumoniae was modeled using PDB ID: 4LFU as a template as well as for Acinetobacter sp., Swiss-model codes A0A2C9TFV2 of AbaR is used for homology modeling (Ahmad et al., 2020; Seleem et al., 2020). These protein sequences were retrieved using Uniprot.

2.10.2 BLAST

In 1990, Stephen Altschul developed the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST). BLAST is useful for determining the degree of local sequence similarity. BlastP compares the query sequence to the template sequence, providing the query coverage score, identity score, and E-value of the target sequence for SdiA of K. pneumoniae and AbaR of Acinetobacter sp.

2.10.3 Prime – Homology modelling (Schrodinger)

By comparing a protein's sequence to those of known proteins, homology modeling may be used to predict the structure of a protein. An alternative term for this method is comparative modeling. The theory states that proteins with similar sequences would also have similar three-dimensional structures. If one of the protein sequences' structures is known, it may be confidently assigned to the unidentified protein. The homology modeling-derived all-atom model is based on alignment with template proteins. The homology modeling procedure is divided into a total of six steps. The first step is template selection, which comprises searching the protein structure database for comparable sequences that might serve as models. The target sequence must then be lined up with the template sequence. The third step is building a main chain atom framework for the desired protein. The fourth step of model creation involves adding and optimizing side chain atoms and loops. The model is refined and optimized regarding energy concerns in the fifth step. An evaluation of the final model's overall quality is the last step.

2.10.4 Model Validation

The final homology model of AbaR and SdiA must be evaluated to guarantee that its structural parts are consistent with physics and chemistry. This necessitates inspecting several structural features, such as bond lengths, near contacts, and -angles, for discrepancies. The correctness of a protein model may also be determined by explicitly considering these stereochemical properties. Experimentally measured structures may be mined for statistical profiles of spatial characteristics and interaction energy, which may reveal defects. This method compares the sequence's statistical properties with the resulting model to ascertain which parts have folded correctly and which do not. If any oddities in the area's structure are found, it will be assumed that there are errors and refined further.

The UNIX tool Procheck (available at https://servicesn.mbi.ucla.edu/PROCHECK/) can verify various physicochemical properties. The model's parameters are then compared against a database of known high-resolution structures. When an abnormality is discovered, the program alerts the user to the areas that need attention.

2.11 Molecular docking

PDB complexes were used to derive receptor structures of AgrC, AbaR, and SdiA proteins by choosing a single protein component and eliminating all fluids and co-factors. To add hydrogens, compute Gasteiger charges, and produce PDBQT files, AutoDock Tools was utilized. The spacing between grid points may be adjusted using one thumbwheel. The standard deviation is 0.375, about the length of a single carbon–carbon bond. This tool lets you explore massive volumes by setting grid spacing values up to 1.0. Before running AutoGrid, you may use a text editor to make changes to the GPF that will allow for more extensive grid spacing options. The grid box's center may be moved using entries and thumbwheels (Morris et al., 1998).

All the five selected ligands and target QS receptor proteins of ATCC Stains No. 1690, 49139, 13883, and 49,139 were optimized and docked. The docking parameter file (DPF) in AutoDock is generated and visualized using Discovery Studio.

3 Results

3.1 Antibacterial assay

The antibacterial activity of methanolic and distilled water extracts of Portieria hornemannii and Halymenia dilatata was tested, and there was no activity found against any of the four strains tested, E. coli, K. pneumoniae, Acinetobacter sp., and S. aureus. Since then, bacteria such as S. aureus and K. pneumoniae have developed resistance to antibiotics such as ampicillin. The zone of inhibition was detected in discs containing ampicillin and algal extracts at a concentration of 20 mg, reported in Table 2 with zone measurements.

s. no

Test microbes

Control with ampicillin disc (10mg)

20mg algal extractsZone of inhibition (in mm)

ampicillin+20 mg extracts

Halymenia dilatata

Portieria hornemanni

Methanol

Distilled water

Methanol

Distilled water

1

K. pneumoniae

Resistant

No zone

–

–

–

–

2

S. aureus

Resistant

No zone

8

8

8

8

3

Acinetobacter sp

Sensitive −1.4 cm zone

No zone

18

20

18

16

4

E. coli

Sensitive-1.0 cm zone

No zone

14

14

10

18

3.2 Anti-biofilm assay

At dosages between 20 and 100 mg/mL, the Halymenia dilatata methanolic extract and the lyophilized Portieria hornemannii extracts prevented biofilm formation in test bacterial pathogens. Therefore, in this assay, the OD value and percentage of biofilm reduction are shown in Table 3.

S.No

Seaweeds

20 mg

40 mg

60 mg

80 mg

100 mg

Control

S. aureus

1

H. dilatata

0.162

0.150

0.138

0.132

0.099

0.177

2

P. hornemannii

0.153

0.151

0.148

0.135

0.098

0.174

E. coli

1

H. dilatata

0.124

0.110

0.099

0.093

0.086

0.173

2

P. hornemannii

0.140

0.126

0.108

0.094

0.082

0.152

K. pneumoniae

1

H. dilatata

0.101

0.095

0.089

0.085

0.077

0.119

2

P. hornemannii

0.095

0.084

0.077

0.075

0.065

0.101

Acinetobacter sp.

1

H. dilatata

0.120

0.100

0.092

0.082

0.072

0.138

2

P. hornemannii

0.116

0.103

0.083

0.077

0.061

0.135

3.2.1 EPS quantification

The methanol extract of Halymenia dilatata and lyophilized extracts of Portieria hornemannii were used against the EPS production of test organisms, which was quantified and revealed decreased EPS production. Untreated test cultures are maintained as control. The 100 mg/mL extracts exhibited 41 %, 35 %, 25 %, and 18 % decrease in EPS production in E. coli, S. aureus, K. pneumoniae, and Acinetobacter sp., respectively.

3.2.2 Visualization of biofilm using tube method

Using this method, biofilm formation by test organisms is easily detected as a visible thick film coating on the inner surface of the tube. In the presence of seaweed extracts, biofilm production was slightly inhibited.

3.2.3 Light Microscopic analysis

Biofilms were seen under a light microscope, as illustrated in Fig. 1, by placing stained cover glasses over slides with the biofilm facing upward. Microscopic observation shows that Acinetobacter sp biofilms were reduced compared to the control.

(a) Acinetobacter sp. biofilm H. dilatata (b) control (c) P. hornemannii (d) E. coli biofilm control (e) P. hornemannii (f) H. dilatata, (g) S. aureus biofilm H. dilatata (h) control (i) P. hornemannii, (j) K. pneumoniae biofilm control (k) P. hornemannii (l) H. dilatata.

3.3 Swimming assay

The swimming ability of test organisms decreased in the presence of 25 mg/mL of extracts. Then, the control plate shows non-motile K. pneumoniae. Further, the maximum inhibition of QS-dependent swimming migration was observed in treatment with S. aureus, Acinetobacter sp, and E. coli extracts.

3.4 Ethidium Bromide-Agar cart wheel assay

Seaweed extracts (25 mg/mL) were tested for their efflux pump inhibitory activity against Acinetobacter sp., E. coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Staphylococcus aureus on MHA agar plates containing 2 mg/L doses of EtBr using the cartwheel assay. The standard of care was a non-seaweed treatment. It's interesting to note that E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and S. aureus all have active efflux in regulation. Lyophilized Portieria hornemannii and Halymenia dilatata methanol extracts block these active efflux pumps. Higher fluorescence intensity relative to the control (Fig. 2) indicated elevated EtBr concentrations.

Efflux pump inhibition assay (a) Control; (b) Treated with methanolic extract (c) Treated with lyophilized extract.

3.5 FTIR Analysis

The methanolic and aqueous extracts of red seaweeds, Portieria hornemannii, and Halymenia dilatata (Fig. 3) are investigated with FTIR, showing different functional groups' presence. The results are interpreted in Table. 4.

FTIR analysis of H. dilatata (a) Aqueous extract (b) Methanolic extract; FTIR analysis P. hornemannii (c) Aqueous extract (d) Methanolic extract.

Methanolic Extracts

Functional Groups

Aqueous Extracts

Functional Groups

P.

hornemanni

Amines, alkanes, aldehydes, phosphines, alkenes, nitro-compounds, alcohols, aromatic compounds, halo compoinds and alkyl aryl ether.

P. hornemanni

Amides, alkanes, phosphines, alkenes, alkyls, alkynes, nitro-compounds, alcohols, aromatic compounds and alkyl halides

H. dilatata

Amides, alkanes, alkenes, alkyls, alcohols, alkyl halides and ethers

H.dilatata

Amides, alkanes, alkyls, phosphines, alkenes, ether, nitro-compounds, alcohols, aromatic compounds and alkyl halides

3.6 GC–MS analysis

The methanolic extracts of Halymenia dilatate and aqueous extracts of Portieria hornemannii were analyzed (Fig. 4) for GC MS. The GC–MS interpretation is shown in the Supplementary Table. S1 and S2. Based on the peak percentage and peak area, the compounds are selected for molecular docking shown in Supplementary Table. S3.

GC–MS analysis of (a) methanolic extracts of H. dilatata, (b) aqueous extracts of P. hornemannii.

3.7 In silico evaluation of Anti-Qs activity

3.7.1 Template identification and homology modeling

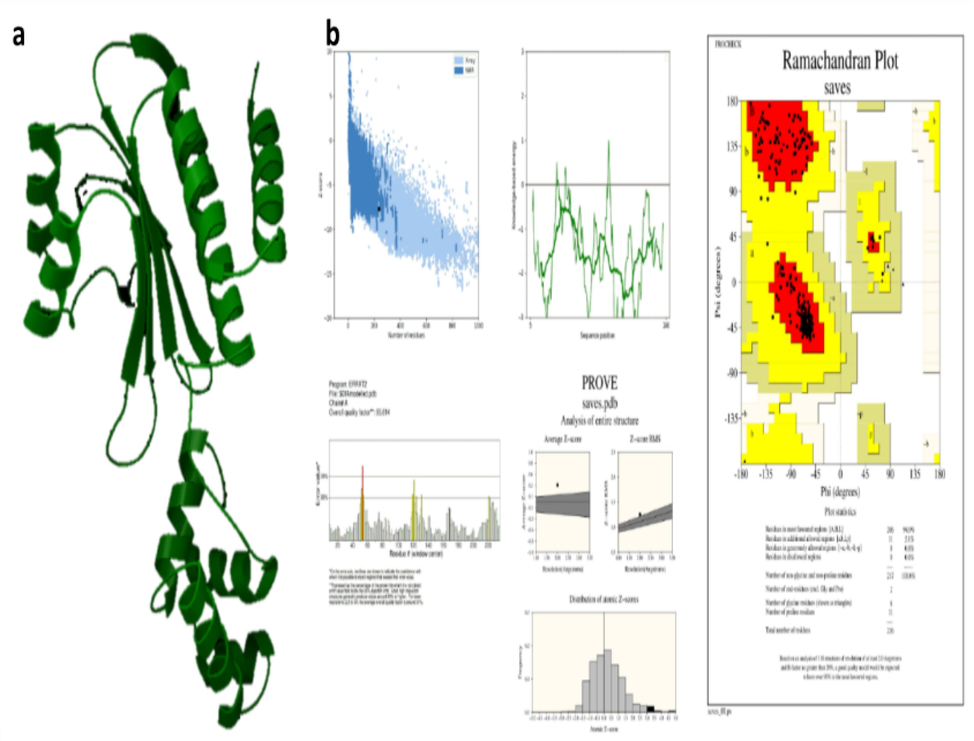

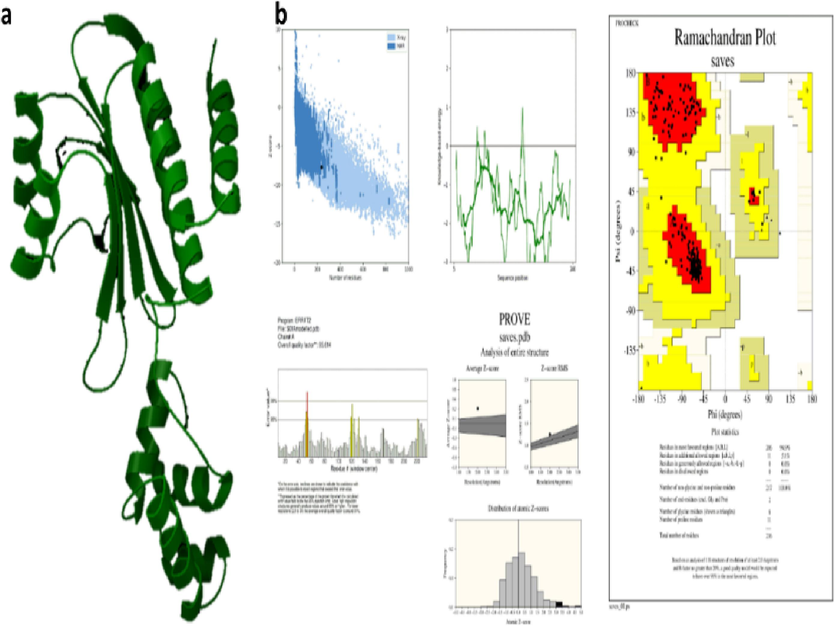

The template structures for SdiA of K.pneumoniae were identified as 4LFU with 100 % identity through BlastP. Likewise, the AbaR protein of the Acinetobacter sp. template was also recognized as 5DIR with 42.03 % similarity. Thus, these proteins are further modeled using Schrodinger (Figs. 5 and 6). Then, the modeled proteins are used to predict the quality using Ramachandran scores and Procheck, which showed 94 % in SdiA and 91 % of AbaR residues in favorable regions. The Z-score is −8––4 in SdiA and AbaR, respectively. Thus, the model protein has good quality.

SdiA modelling (a) Modelled protein structure (b) Validation of SdiA.

AbaR modelling (a) Modelled protein structure (b) Validation of AbaR.

3.7.2 Molecular docking

All five selected compounds from red seaweed extracts are docked with each QS receptor protein of test pathogens (Supplementary Figure S2, S3, S4, and S5). The docking scores and protein–ligand interactions are shown in (Supplementary Tables. S4, S5, S6, and S7). The compounds such as Hexamethyl Cyclotrisiloxane, Benzo[h]quinoline, 2,4-dimethyl, and 5-Methyl-2-phenylindolizine from H. dilatata and P. hornemannii, respectively, showed adequate binding energy along with inhibitor constant. Then, 5-methyl-2-phenylindolizine has H-bonding with Trp 67 and Thr 298 amino acid residues in 4LFU, 4BXI, and modelled SdiA protein.

4 Discussion

The present study investigates the potential of red seaweeds such as Portieria hornemannii and Halymenia dilatata for anti-QS activity and to control the virulence of Klebsiella pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, and Acinetobacter sp. The QS autoinducers, synthase, and receptors are responsible for the virulence expressions, mainly including biofilm formation and motility. The antibacterial activity of the seaweed extracts was tested against test pathogens, and Staphylococcus aureus and Klebsiella pneumoniae showed resistance even to ampicillin. Then, the extracts were again tested in combination with ampicillin antibiotics that showed large zone formation in bacterial strains other than Klebsiella pneumoniae when compared to control ampicillin discs. Weigel et al., 2007 revealed that some pathogenic microorganisms like S. aureus resist antibacterial, and their biofilms are essential for MDR. The QS system will not affect the bacterial growth (Tay and Yew, 2013). Therefore, targeting QS is another way to resolve antibiotic resistance and virulence.

Bhuyar et al. (2019) employed the red seaweed Kappaphycus alvarezii to evaluate its anti-oxidant and antibacterial activities against B. cereus. They used hot water and ethanol extraction methods, yielding 33 % and 17 %, respectively. Likewise, the present study showed a higher yield in aqueous extract of H. dilatata (30 %) and P. hornemannii (18 %). However, the yield in the methanolic extract obtained a lower quantity, such as 18 % in H. dilatata and 4.6 % in P. hornemannii.

Similarly, in this study, red seaweeds such as P. hornemannii and H. dilatata reduced the biofilm formation, EPS production, swimming motility, and efflux pump production, which is one of the essential factors affecting antibiotic resistance of pathogenic bacteria. In microbial cells, drug blockage is caused by efflux pump expression. The current study on inhibiting efflux pumps utilized EtBr as a marker. It showed that efflux pumps present in S. aureus strain ATCC 1690, K. pneumoniae, and E. coli were effectively inhibited by the red seaweed extracts.

Singh et al., 2016 performed molecular docking studies for anti-QS of ginger rhizome. Their findings showed that polyphenolic compounds have the best affinity with CviR and LasR QS receptors. Seleem et al., 2020) researched anti-QS against Acinetobacter sp. using erythromycin, chloroquine, and levamisole drugs. They used both AbaI and AbaR for docking studies.

Therefore, in silico study in the present work results showed that all the QS receptor proteins of K. pneumoniae, E. coli, Acinetobacter sp., and S. aureus effectively bound with the compounds of P. hornemannii and H. dilatata more similarly, these extracts functionally reduced the QS dependent biofilm formation in vitro studies. Thus, these compounds from marine red seaweeds interfere with the QS network to combat the virulence that pathogenic bacteria express. Public health is at risk from diseases brought on by harmful microbes, including bacteria, viruses, and yeasts. The majority can infect medical equipment and high-touch surfaces, increasing and forming resistant biofilms, making it difficult to remove using disinfectants altogether. It is, therefore, essential to create anti-microbial materials with anti-QS and anti-biofilm properties since quorum sensing-mediated processes, including swarming motilities and biofilm formation, aid in developing resistance and spreading these microorganisms.

5 Conclusion

Portieria hornemannii and Halymenia dilatata have bioactive compounds against the QS mechanism of pathogenic organisms such as K. pneumoniae, E. coli, Acinetobacter sp., and S. aureus. Targeting the receptor of QS will block the signals from binding to the receptors. Therefore, the virulence expressions are controlled by the QS inhibitors. Correspondingly, these compounds can inhibit efflux pumps. Thus, the virulence and antibiotic resistance of bacteria were influenced by these marine red seaweeds, confirmed by in vitro and silico studies. These QS inhibition techniques could be used to treat pathogens that cause nosocomial infections, pathogenicity, and biofilms. As a result, this method can manage QS without interfering with bacterial development. QS Inhibitors have been applied in different fields, such as marine environments, agriculture, food processing, membrane bioreactors, and medical devices to prevent bacterial biofilm infections.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Prakash Piruthivraj: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Software. B.R. Maha Swetha: . A. Anita Margret: . A. Sherlin Rosita: Methodology, Software. Parthasarathi Rengasamy: Writing – review & editing. Rajapandiyan Krishnamoorthy: Resources. Mansour K. Gatasheh: Resources. Khalid Elfaki Ibrahim: Resources. Sekhu Ansari: Resources. Natesan Vijayakumar: Formal analysis, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Acknowledgment

We thank the Researchers Supporting Project (RSP2024R393), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Determination of optimum incubation time for formation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and biofilms in microtiter plate. Bull. Natl. Res. Centre. 2019;43(1):1-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cocktail of CuO, ZnO, or CuZn Nanoparticles and Antibiotics for Combating Multidrug-Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa via Efflux Pump Inhibition. ACS Appl. Nano Mater.. 2021;4(9):9799-9810.

- [Google Scholar]

- New method for detecting slime production by coagulase negative staphylococci. J. Clin. Pathol.. 1989;42(8):872-874.

- [Google Scholar]

- The cytoplasmic loops of AgrC contribute to the quorum-sensing activity of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Microbiol.. 2021;59(1):92-100.

- [Google Scholar]

- Structural insights into the molecular mechanism of Escherichia coli SdiA, a quorum-sensing receptor. Acta Crystallographica Section D: Biol. Crystallogr.. 2014;70(3):694-707.

- [Google Scholar]

- Automated docking using a Lamarckian genetic algorithm and an empirical binding free energy function. J. Comput. Chem.. 1998;19(14):1639-1662.

- [Google Scholar]

- 2, 5-Piperazinedione inhibits quorum sensing-dependent factor production in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. J. Basic Microbiol.. 2012;52(6):679-686.

- [Google Scholar]

- Structural and mechanistic roles of novel chemical ligands on the SdiA quorum-sensing transcription regulator. MBio. 2015;6(2):e02429-e2514.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antibiofilm and quorum sensing inhibitory potential of Cuminum cyminum and its secondary metabolite methyl eugenol against Gram negative bacterial pathogens. Food Res. Int.. 2012;45(1):85-92.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevention of biofilm formation by quorum quenching. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol.. 2020;104(5):1871-1881.

- [Google Scholar]

- Exploring the potential: Inhibiting quorum sensing through marine red seaweed extracts–A study on Amphiroa fragilissima. J. King Saud Univ.-Sci.. 2024;103118

- [Google Scholar]

- Inhibition of biofilm formation and quorum sensing mediated virulence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa by marine sponge symbiont Brevibacteriumcasei strain Alu 1. Microb. Pathog.. 2021;150:104693

- [Google Scholar]

- Drugs with new lease of life as quorum sensing inhibitors: for combating MDR Acinetobacter baumannii infections. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis.. 2020;39(9):1687-1702.

- [Google Scholar]

- In silico identification of polyphenolic compounds from the grape fruit as quorum sensing inhibitors. J Chem Pharm Res. 2016;8(5):411-419.

- [Google Scholar]

- Influence of the AgrC-AgrA complex on the response time of Staphylococcus aureus quorum sensing. J. Bacteriol.. 2014;196(15):2876-2888.

- [Google Scholar]

- Development of quorum-based anti-virulence therapeutics targeting Gram-negative bacterial pathogens. Int. J. Mol. Sci.. 2013;14(8):16570-16599.

- [Google Scholar]

- A factor that positively regulates cell division by activating transcription of the major cluster of essential cell division genes of Escherichia coli. EMBO J.. 1991;10(11):3363-3372.

- [Google Scholar]

- High-level vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates associated with a polymicrobial biofilm. Anti-microbial Agents Chemother.. 2007;51(1):231-238.

- [Google Scholar]

Appendix A

Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2024.103188.

Appendix A

Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article: