Translate this page into:

Optical, structural and semiconducting properties of Mn doped TiO2 nanoparticles for cosmetic applications

⁎Corresponding author. leda@imdlaboratories.gr (Leda G. Bousiakou)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticles, have been routinely used in cosmetic and sunscreen applications, due to their ability to absorb in the UV spectrum. Nevertheless, one of the main disadvantages has been the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), especially the hydroxyl radical, upon photoexcitation of titania. In this work, we investigate TiO2 nanoparticles doped with 0.6–0.7% manganese (Mn), based in the more stable rutile polymorph of titania. In particular, while the anatase crystal form has the ability to destroy almost any organic matter under UV illumination, rutile is less photoreactive, and with Mn doping its photoactivity is reduced further. In particular, we study its optical, structural and semiconducting properties via the Seebeck effect and show that the material displays p-type characteristics. This is very significant because it shifts the energy levels with respect to formation of hydroxyl free radicals. This ensures that for Mn doped p-type titania it is not energetically possible for the hole created in the valence band by photoexcitation to create an OH. free radical and this may explain its low photoreactivity. It also means that this material can act as a very effective scavenger for hydroxyl free radicals.

Keywords

Titania

Manganese

TiO2:Mn

Doped

Raman

SEM

TEM

XRD

Seebeck effect

1 Introduction

TiO2 is a semiconducting material that has received wide attention ever since Fujishima and Honda (1972) discovered the photocatalytical splitting of water on a TiO2 electrode under ultraviolet (UV) light. Over the past decades, TiO2 has found applications in many promising areas ranging from photovoltaics and photocatalysis, to pigments and cosmetic applications (Hashimoto et al., 2005, Ahmad et al., 2018). In addition, TiO2 is attractive as it can be mass-produced at a low cost in different sizes, shapes and phase compositions, each possessing unique physiochemical properties. These include microspheres, nanorods, nanotubes and nanowires, for numerous applications (Krishnan et al., 2021).

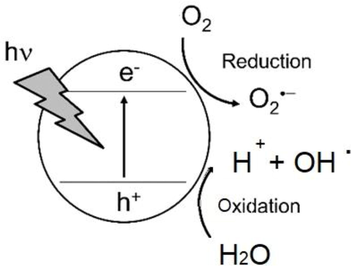

In the field of personal care products and cosmetics, TiO2 can be found in a number of preparations. In particular, titania is incorporated in microcrystalline form in toothpastes, as a whitener and an abrasive as well as in different soaps, hair colours and skin products as a pearlescent colorant and opacifier (Berardinelli and Parisi, 2021). Its bright white appearance, originates from its light scattering properties and large refractive index (Bodurov et al., 2014). Currently it is approved for use in cosmetic and personal care products, both by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA, 2021), as well by the EU Commission via regulation 1857/2019 (EU, 2019). In the area of sunscreen applications, TiO2 has been used in its nanoform for a number of years, considering that at sizes below100nm, its whiteness is displaced by transparency, which creates a favourable appearance when applied to skin (Tanvir et al., 2015). In addition, as a result of particle size reduction, there is a shift of its absorption spectrum from the UVA to the UVB, which is mostly responsible for sunburns and skin cancer. Currently TiO2 is approved in sunscreen formulations, in concentrations between 2% and 15%, while its loading can reach up to 25% in preparations (Morsella et al., 2016). Nevertheless, one of the main disadvantages of TiO2 is the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) upon photoexcitation, including superoxide radicals (O2•−), hydroxyl radicals (OH•), and singlet oxygen 1O2. In particular, reactive oxygen species arise from the transfer of light-initiated carriers to the TiO2 surface and react with oxygen or water (Fig. 1.1), playing an essential role in the photocatalytic nature of titania, which can lead to skin damage Dunford et al. (1997) first identified that it is actually hydroxyl radicals are the most applicable in the area of titania based sunscreen applications.

Reactive oxygen species formation in TiO2 via UV irradiation (Hirakawa, 2015).

Moreover, titania is more photoreactive in its anatase crystal form compared to rutile, which is also more thermodynamically stable (Luttrell et al., 2014). In fact, anatase is capable of destroying virtually any organic matter via the ROS and has therefore been widely exploited in many processes ranging from water and air purification, to self-cleaning surfaces and photodynamic treatment of cancer (Al-Enizi et al., 2020). On the other hand, rutile, is preferred for applications in cosmetic brands, as it ensures minimum skin damage.

One of the production routes for TiO2 nanoparticles towards sunscreen applications is via doping with other elements, in order to fine-tune the TiO2 properties. Manganese has been successfully used to reduce the unwanted photoactivity of nano-sized TiO2 (Wakefield et al., 2013, Wakefield and Stott, 2007). In this study, we investigate the optical, structural and semiconducting nature of Optisol, a commercial TiO2:Mn nanocrystalline powder used in cosmetic applications in an aim to understand how it leads to a less photoactive substance for sunscreen applications (Knowland et al., 1998).

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

Unless otherwise indicated, reagents were obtained from Merck and were used as received. Commercial, TiO2:Mn nanocrystalline powder Optisol (Oxonica Materials Ltd) was used. A thick TiO2:Mn based paste was obtained by mixing Optisol with 70% EtOH before concentrating the mixture in a rotary evaporator. The paste was then doctor bladed on a microscope slide and sintered in a SNOL 3/1100 muffle furnace at 500 °C in order to conduct the Seebeck effect measurements Following this, Raman and XRD measurements were conducted on the same samples.

2.2 Characterizations

The TiO2:Mn nanopowder was examined using an FE-SEM JEOL 7000F- scanning electron microscope (SEM), while transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was performed with an JEM 2100, 200 kV analytical electron microscope. The diffuse reflectance spectra were collected with a Shimadzu UV/VIS/NIR spectrometer (Tokyo, Japan), model UV-3600. For the Seebeck effect measurements, hot plates and a multimeter were used. Following that, the Raman spectra of the samples were recorded using 532 nm excitation from a diode laser using a Jobin Yvon T64000 Raman Spectrometer in the backscattered mode. Finally, the crystal structure for the samples was measured by a Siemens D5000 diffractometer using CuK(alpha) radiation with an operating voltage of 20 V and angle of incidence 3° in all cases.

3 Results and discussions

3.1 Electron microscopy studies and EDS analysis

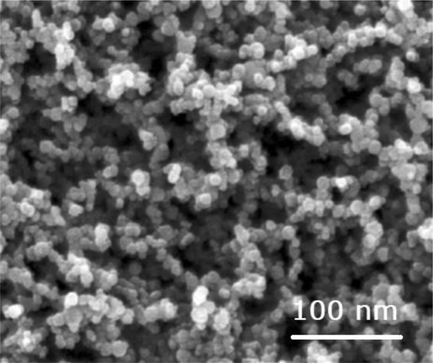

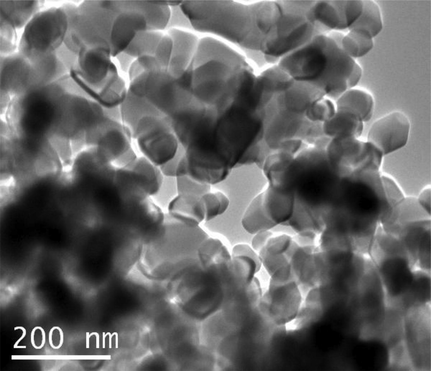

The TiO2:Mn nanopowder, can be seen under scanning electron microscopy (Fig. 3.1a) and TEM (Fig. 3.1b), A primary particle size ranging from approximately 20 nm diameter to approximately 80 nm diameter/length is observed. Additionally, most particles are roughly isometric in shape. The agglomeration observed is an artifact of the method of sample preparation brought about by surface tension effects as the droplets dried on the carbon coated electron microscope grids.

SEM for the TiO2:Mn nanopowder based on the rutile crystalline phase.

TEM analysis of the TiO2:Mn nanopowder sample.

According to Barnard (2010), particle size plays and important role both in transparency, sun protection factor (SPF) and ROS generation. In particular, there is an increase in both transparency and SPF with decreasing size of nanoparticles. Additionally, a peak ROS production is identified at 33 nm in size for undoped TiO2. In this regard, the average size of the engineered TiO2:Mn nanoparticles ensures a balance between good transparency, without enhancing ROS production.

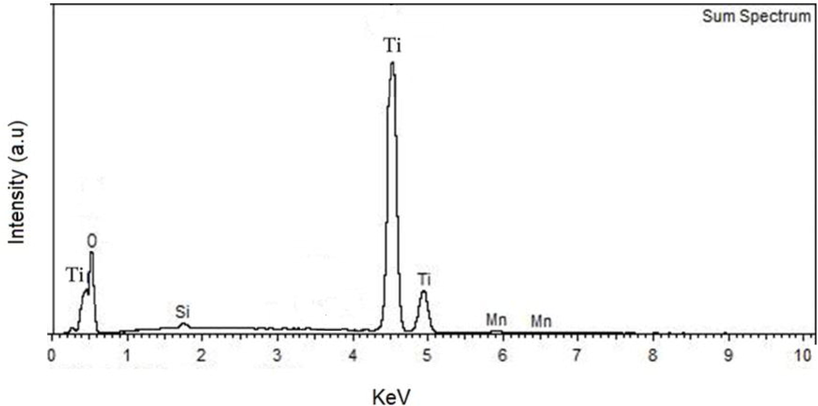

Below in Fig. 3.2 the energy dispersive x-ray spectrum measurements (EDS) of the TiO2:Mn based film on microscope glass can also be seen. The spectrum reveals that the major compositions of the deposited film are titanium (Ti) and oxygen (O), manganese (Mn). Traces of Si can be seen due to the substrate material.

EDS of the deposited TiO2:Mn film on microscope slide.

3.2 XRD and Raman results

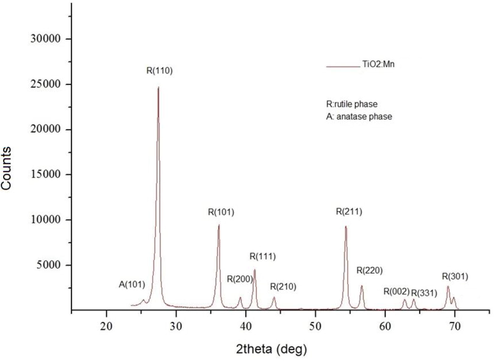

XRD patterns for the films are shown in Fig. 3.3, demonstrating that the samples are predominantly in the rutile phase (Zheng et al., 2015). There are no additional diffraction peaks related to manganese oxides, suggesting Mn exists as a dopant impurity. In particular, characteristic strong peaks related to the rutile phase are observed at 27.35°, 36.01°, and 54.24°, while weaker peaks are seen at the following diffraction angles 39.25°, 41.12°, 44.05°, 54.14°, 56.64°, 62.71°, 64.20° (Thamaphat et al., 2008). A split peak is noted at 68.93° and 69.97°, related to the K(alpha)1 and K(alpha)2 doublet (Joni et al., 2018). It should be noted that the K(alpha) line actually consists of the K(alpha)1 (CuK(alpha)1 = 1.540598 Å) and K(alpha)1 (CuK(alpha)2 = 1.54439 Å) lines that differ slightly in wavelength, leading to such double peaks in the XRD spectrum. All the diffraction angles can be indexed to the tetragonal rutile structure of TiO2 with a good agreement to the standard JCPDS entry code No. 00-001-1292. A weak peak observed at 25.24° can be indexed to the tetragonal anatase structure of TiO2 (JCPDS No. 00-001-0562). Furthermore, we believe that the manganese was uniformly distributed in the rutile, because we did not see any evidence for phases on manganese oxides in the XRD or TEM. Furthermore, the ionic radii are close enough to ensure that uniform distribution of the manganese is likely.

The TiO2:Mn XRD spectra.

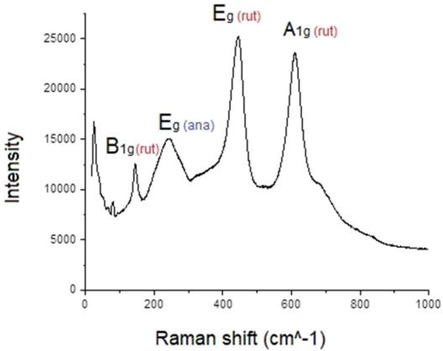

Subsequently Raman spectroscopy was used for further structural investigations as seen in Fig. 3.4. The Raman spectra of titania polymorphs are distinctive enough and they are very useful for identification of various TiO2 phases. According to the literature, rutile TiO2 has four vibrational modes around 145 cm−1 (B1g), 445 cm−1 (Eg), 610 cm−1 (A1g), and 240 cm −1 for second-order effects (Mazza et al., 2007). The analysis of the Raman spectra of theTiO2:Mn sample shows predominantly the presence of the rutile characteristic stretching peaks at 145 cm−1, 445 cm−1, and 611 cm−1 that correspond to the symmetries of B1g, Eg, and A1g, respectively, while a peak at 241 cm−1 accounts for second order effects, such as multiple phonon scattering processes. The results show that there is agreement between the XRD and Raman spectra.

The Raman Spectrum of the TiO2:Mn film.

3.3 Seebeck effect results on the semiconducting nature of Optisol

The Seebeck effect is employed in order to determine whether the nanocrystalline TiO2:Mn paste creates an n- or p-type semiconductor surface. In general, we know that undoped titanium dioxide is an intrinsic, n-type semiconductor as a result of the oxygen vacancies in the TiO2 lattice. The oxygen vacancies act as electron donors, in contrast with p-type semiconductors which contain electron acceptors and where the charge carriers are holes rather than electrons. For this purpose, the Seebeck effect was employed (Jaziri et al., 2020, Hadley, 2020). In general, the Seebeck effect relates the gradient of the electrochemical potential to the temperature gradient as show below:

In order to perform the measurement a small laboratory scissor jack stand at room temperature and a heated surface (hot plate) were used. Two aluminium slabs were placed at each surface where the sample could be placed. The temperature was also measured using a thermocouple. Our set up was calibrated using an n and p doped silicon wafer, establishing that our doped titania showed p-type characteristics. In particular, with the hot plate at 120 °C a negative potential at approximately −50 mV was measured.

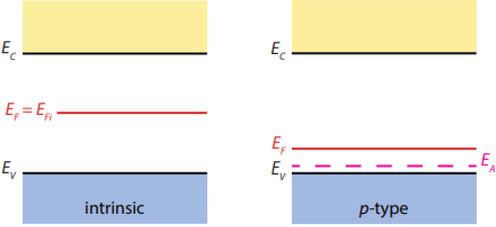

Titania is often doped with other transition metals, in order to impart visible light photocatalytic activity to titania by narrowing its band gap. For this purpose, transition metals are often used with the following redshift effectiveness V > Cr > Mn > Fe > Ni (Moma and Baloyi, 2019). In our case, as rutile TiO2 is doped, the observation that a p-doped behaviour is recorded, implies a shift in the position of the Fermi level towards the valence band. In particular, the substitution of Ti4+ in the TiO2 lattice by transition metal Mn3+ ions leads to the introduction of acceptor energy levels EA and shifting of the Fermi level and band gap as in Fig. 3.5 below:

Shifting of the Fermi level and band gap upon doping.

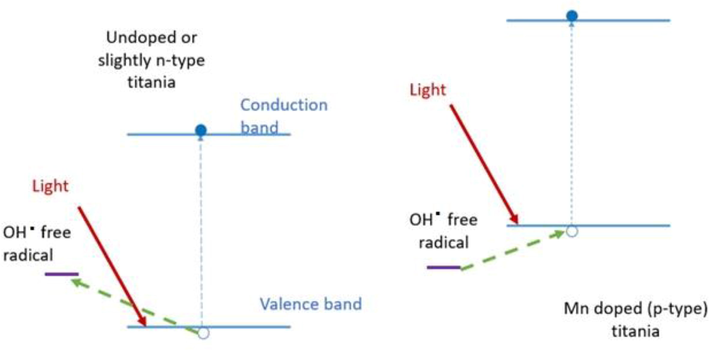

Moreover, this behaviour explains that while upon illumination, undoped titania leads to the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), for Mn doped p-type titania it is not energetically possible for the hole created in the valence band to create an OH. free radical as seen in Fig. 3.6 below:

Energy diagrams showing the process of ROS formation in undoped and p doped titania.

3.4 Energy band gap measurements

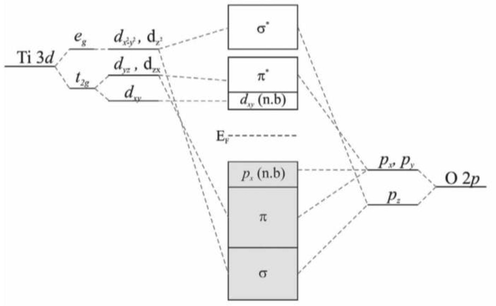

In general, undoped, TiO2 is in itself an intrinsic semiconductor. It’s molecular orbit energy-level diagram is shown in Fig. 3.7, noting that the structure of TiO2 is a result of the hybridisation of the 2p orbitals of oxygen and the 3d ones of titanium.

Titania energy levels (Greiner and Lu, 2013).

It is in general a wide-band gap semiconductor and as a result it absorbs only minimally in the visible. It has three polymorphs: anatase, rutile and brookite (Oi et al., 2016). According to Lance (2018) there is a lack of consistency in the literature with regarding to the band gaps of TiO2 polymorphs (Table 3.1) with values corresponding to both a direct and indirect band gap measured for all rutile, anatase and brookite.

Rutile (eV)

Anatase (eV)

Brookite (eV)

Ref/Year

3.01(I)–3.37(D)

3.20(I)–3.53(D)

3.13(I)–3.56(D)

Reyes-Coronado et al 2008

3.45(D)

Alotaibi et al., 2018

3.0 (I)

3.2(I)

3.03, 0.05, 3.13 (I)

Lin et al., 2012

3.0 (D)

3.2(D)

Kim et al., 2014

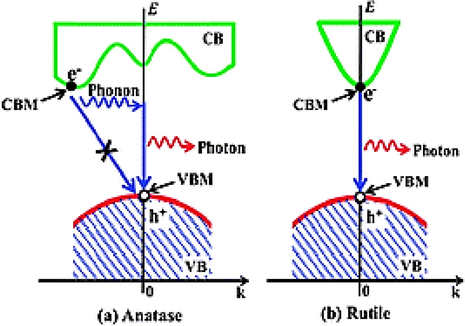

According to Zhang et al (2014), first principle calculations using Density Functional Theory show rutile to be a direct band gap material, whereas anatase, is an indirect band gap semiconductor (Fig. 3.8). In particular, if the minimum point of the conduction band and the maximum point of the valence band appear at the same value of k, then we have a direct energy band gap semiconductor, otherwise the semiconductor is called indirect. In general, as can be seen in Fig. 3.8 electron-hole recombination in indirect semiconductors in low, which in direct semiconductors is immediate with the release of a photon. In this regard, the indirect nature of the anatase bandgap can account for the larger photoexcited carrier lifetimes, thus justifying the more photocatalytic nature of anatase compared to rutile.

The indirect band gap of anatase and the direct band gap of rutile as predicted by Zhang et al (2014).

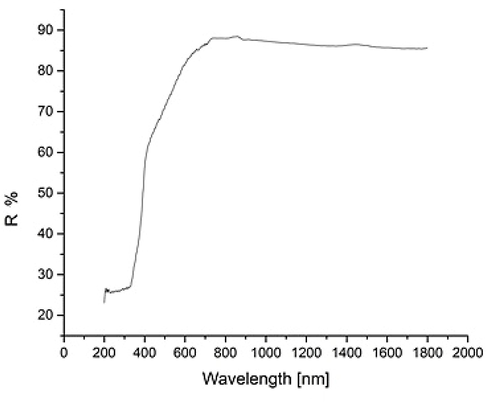

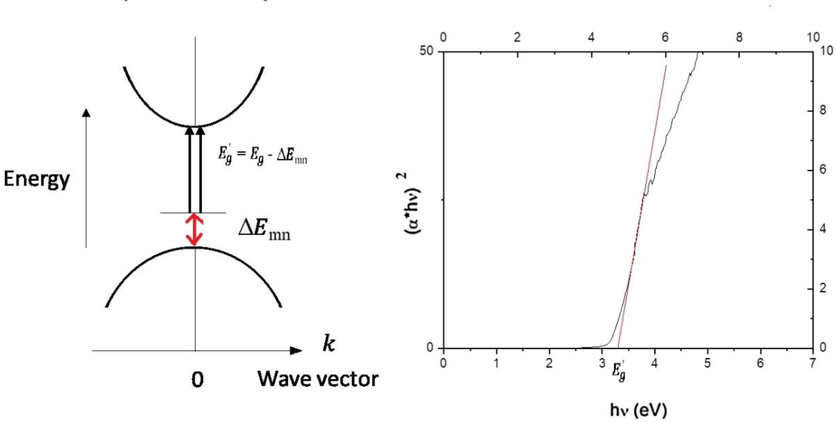

In order to find the band gap of the material in this work, diffuse reflectance spectra (DRS) of TiO2:Mn were studied using a Shimadzu spectrophotometer UV-3600 In particular, relative reflectance measurements were taken from the TiO2:Mn, Optisol nanopowder sample relative to the amount of reflected light measured from a barium sulphate (BaSO4) reference plate. The relative reflectance is calculated based on assuming the reference plate has a reflectance of 100 %. Below, in Fig. 3.9 the DRS of the TiO2:Mn exhibits due to the presence of the dopant visible light absorption below ∼700 nm, in comparison with pure rutile (Praveen et al 2019).

Diffuse UV–Visible Reflectance spectra for the TiO2:Mn sample.

Subsequently the energy band gap for TiO2:Mn is estimated. In particular, Tauc et al (1966) and Davis and Mott (1970) proposed an energy dependent absorption coefficient for obtaining the band gap of a material, i.e.:

The direct band gap for TiO2:Mn.

In particular Mizushima et al. (1979), used photocurrent and electron spin resonance (ESR) measurements to determine, relative to the conduction band, the 3dn manifold energies at substitutional impurities in TiO2:Mn. It was determined that upon doping a band of surface states E1 centered at 2 eV appears below the conduction band edge Ec, as well as a band of bulk native-defect cation-vacancy states extending from near the valence band edge to about 1.9 eV below Ec. In particular, the introduction of manganese into the TiO2 lattice results in Mn3+ ions sitting on the Ti4+ lattice acting as Mn3+ p-type dopants at −1.9 eV. The MnO energy level and the hole associated with it, lie almost exactly in the middle of the band gap, giving a level for any photogenerated charges to de-excite. This reduces free radical generation by more than 95%. Moreover, they showed that an increase of surface electron mobility requires a net transfer of bulk acceptor electrons to surface states that increases with temperature. This requires that the ratio of the E2/E1 electrons photoexcited to the conduction band to be significantly greater than unity for hv 2.5 eV, a character consistent with the p-type nature of the samples.

4 Conclusions

TiO2:Mn nanoparticles as in Optisol, are based on rutile, the most stable form of TiO2 that is also less photoactive than the anatase crystal polymorph. In particular, the average size of the engineered TiO2:Mn nanoparticles, which is as an average of over 30 nm, ensures a balance between sufficient transparency, without enhancing ROS production, a feature essential in cosmetic industry to minimize skin damage. In particular, rutile being a direct semiconductor accounts for shorter photoexcited carrier lifetimes, justifying this less photocatalytic nature, compared to anatase, which is an indirect semiconductor. Furthermore, the introduction of manganese, Mn3+ ions, into the rutile TiO2 lattice results in p-type dopant energy levels. In addition, the MnO energy level and the hole associated with it, lie almost exactly in the middle of the band gap, giving a level for any photogenerated charges to de-excite. Moreover, it can be argued that for Mn doped p-type titania it is not energetically possible for the hole created in the valence band to create an OH. free radical. As a result, above processes reduce free radical generation in TiO2:Mn by more than 95%.

Acknowledgement

This work has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 101007299.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Phase controlled synthesis of bifunctional TiO 2 nanocrystallites via d -mannitol for dye-sensitized solar cells and heterogeneouscatalysis. RSC Adv.. 2020;10(25):14826-14836.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chemical vapor deposition of photocatalytically active pure brookite TiO2 thin films. Chem. Mater. 2018;30(4):1353-1361.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, characterization and dielectric properties of TiO2-CeO2 ceramic nanocomposites at low titania concentration. Bull. Mater. Sci.. 2018;41:99.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- One-to-one comparison of sunscreen efficacy, aesthetics and potential nanotoxicity. Nature Nanotechnol.. 2010;5(4):271-274.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- TiO2 in the food industry and cosmetics. In: Metal Oxides, Titanium Dioxide (TiO₂) and Its Applications. Elsevier; 2021. p. :353-371.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Refractive index investigations of nanoparticles dispersed in water. J. Phys. Conf. Ser.. 2014;558:012062.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Conduction in non-crystalline systems V. Conductivity, optical absorption and photoconductivity in amorphous semiconductors. Philos. Mag.. 1970;22:0903-0922.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chemical oxidation and DNA damage catalysed by inorganic sunscreen ingredients. FEBS Lett.. 1997;418:87-90.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- EU, Commission Regulation 1857/2019 as of 6.11. 2019 amending Annex VI to Regulation (EC) No 1223/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council on cosmetic products, Off. J. Eur. Union. 2019, L286/3.

- FDA, US Food and Drug Administration, 2021, 21-Food and Drugs. Code of Federal Regulations CFR 73.2575.

- Electrochemical photolysis of water at a semiconductor electrode. Nature. 1972;238:37-38.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Thin-film metal oxides in organic semiconductor devices: their electronic structures, work functions and interfaces. NPG Asia Mater.. 2013;5(7)

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hadley P., 2020, Lecture Notes. TU Graz, Austria. Available online from: https://lampx.tugraz.at › ∼hadley › ss2/lectures17/may19.pdf. Accessed on 02.07.2021.

- TiO2 photocatalysis A historical overview and future prospects. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys.. 2005;44(12):8269-8828.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hirakawa K., 2015. Fundamentals of medicinal application of titanium dioxide nanoparticles. In: Mahmood Aliofkhazraei (Eds.), Nanoparticles Technology. https://doi.org/10.5772/61302. Available from: https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/49185.

- A comprehensive review of thermoelectric generators: technologies and common applications. Energy Rep.. 2020;6(7):264-287.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Characteristics of TiO 2 particles prepared by simple solution method using TiCl 3 precursor. J. Phys.: Conf. Ser.. 2018;1080:012042.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Brookite TiO2 thin film epitaxially grown on (110) YSZ substrate by atomic layer deposition. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2014;6(15):11817-11822.

- [Google Scholar]

- Knowland J., Dobson P., Wakefield G., 1998. Ultraviolet Light Screening Compositions, US20060039875A1.

- Noticeable improvement in the toxic gas-sensing activity of the Zn doped TiO2 films for sensing devices. New J. Chem.. 2021;45:10488-10495.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lance, 2018. Optical Analysis of Titania: Band Gaps of Brookite, Rutile and Anatase, Thesis. Oregon State University, USA.

- Synthesis of high-quality brookite TiO2 single-crystalline nanosheets with specific facets exposed: tuning catalysts from inert to highly reactive. J. Am. Chem. Soc.. 2012;134:8328-8331.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Why is anatase a better photocatalyst than rutile? - Model studies on epitaxial TiO2 films. Sci. Rep.. 2014;4:4043.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- How to correctly determine the band gap energy of modified semiconductor photocatalysts based on UV–Vis spectra. J. Phys. Chem. Lett.. 2018;9(23):6814-6817.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mazza T., Barborin E., Piseri P., Milani P., Cattaneo D., Li Bassi A., Bottani C.E., Ducati C., 2007. Raman spectroscopy characterization of TiO2 rutile nanocrystals, Phys. Rev. B 75, 045416. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.75.045416.

- Moma J., Baloyi J., 2018. Modified titanium dioxide for photocatalytic applications, Photocatalysts - Applications and Attributes, Sher Bahadar Khan and Kalsoom Akhtar, IntechOpen, https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.79374. Available from: https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/62303.

- Improving the sunscreen properties of TiO2 through an understanding of its catalytic properties. ACS Omega. 2016;1(3):464-469.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Recent advances of titanium dioxide (TiO2) for green organic synthesis. RSC Adv.. 2016;6(110):108741-108754.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Praveen P., Viruthagirib G., Mugundanc S., Jothibasd M., Prakashc M, Sagayaraja S., 2019. Structural, functional and optical characters of TiO2 nanocrystallites: anatase and rutile phases, St. Joseph’s J. Hum. Sci. 6(1),43–53 https://sjctnc.edu.in/6107-2/.

- Phase-pure TiO2 nanoparticles: anatase, brookite and rutile. Nanotechnology. 2008;19(14):145605.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Toxicity associated with the photo catalytic and photo stable forms of titanium dioxide nanoparticles used in sunscreen. MOJ Toxicol.. 2015;1(3):78-94.

- [Google Scholar]

- Optical properties and electronic structure of amorphous germanium. Phys. Status Solidi B. 1966;15(2):627-637.

- [Google Scholar]

- Thamaphat K., Limsuwan P., Ngotawornchai B., 2008. Phase characterization of TiO2 powder by XRD and TEM kasetsart. J. Nat. Sci. 42 (5) 357-361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. clinbiochem.2011.08.962.

- Wakefield G., Stott J., 2007. Photostabilization of organic UV-absorbing and anti-oxidant cosmetic components in formulations containing micronized manganese doped titanium oxide. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 29, 139–141. .

- Modified titania nanomaterials for sunscreen applications: reducing free radical generation and DNA damage. Mater. Sci. Technol.. 2013;20(8):985-988.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- New understanding of the difference of photocatalytic activity among anatase, rutile and brookite TiO2. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys.. 2014;16(38):20382-20386.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng K., Zhang T.C., Lin P., Han Y.-H., Li H.-Y., Ji R.-J., Zhang H.-Y., 2015. 4-Nitroaniline degradation by TiO2 catalyst doping with manganese. J. Chem. 2015. Article ID 382376. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/382376.