Zoonotic risk and public health hazards of companion animals in the transmission of Helicobacter species

⁎Corresponding author at: Department of Botany and Microbiology, College of Science, King Saud University, P.O. Box 2455, Riyadh 11451, Saudi Arabia. imoussa1@ksu.edu.sa (Ihab M. Moussa)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Objective

Helicobacteriosis is worldwide infection caused by Helicobacter species that affects both humans and animals. The current work correlated the zoonotic and public health repertoire of Helicobacter species in companion animals (dogs and cats).

Methods

Samples were collected from apparently healthy dogs (70), cats (65), and 70 human patients who had been in contact with these animals in the Cairo and Giza governorates. The samples included serum, feces, and stool samples and biopsies of gastric fundus fragments (∼5 mm). All samples were examined by culture, biochemical analysis, serology, and molecular identification.

Results

Helicobacter species were detected at a rate of 43.4% by PCR. H. heilmannii was more predominant, with a rate of 16%, whereas H. pylori was detected at 6%. H. pylori and H. heilmannii were isolated from both human and companion samples, whereas all samples were negative for H. felis.

Conclusion

Dogs and cats were reservoirs and played a major source in human helicobacters infection.

Keywords

Helicobacteriosis

H. heilmannii

H. pylori

H. felis

Gastric ulcer

1 Introduction

The bacteria of dog were firstly found in the stomach mucosa and named as Spirillum (Rappin, 1958); subsequently, they were called Spirochete, then Campylobacter, and currently they are grouped in the Helicobacter genus (Lockard and Boler, 1970; Owen, 1998). The work was also documented by Bizzozero and Salomon in dogs, cats, and rats (Bizzozero, 1893; Salomon, 1896). The Helicobacter genus comprises approximately 21 species with gastric, intestinal, or hepatic distribution. The gastric Helicobacter species include H. felis, H. bizzozeronii, H. salomonis, “H. heilmannii,” “Flexispira rappini,” and H. bilis in dogs and cats and H. pylori in humans. The intestinal forms includes H. fennelliae, H. cinaedi, H. canis, and “F. rappini” in humans, dogs, and cats and H. hepaticus, H. bilis, H. rodentium, H. muridarum, and “F rappini” in mice. H. hepaticus and H. bilis in mice, H. canis in dogs, and possibly H. pylori in humans are hepatic Helicobacter species (Shinozaki et al. 2002).

Many studies have concluded that gastric Helicobacter infections are present in both apparently healthy dogs and in those with clinically apparent gastric disease (Okubo et al. 2017). Helicobacter species vary according to geographic region and exhibit a prevalence of 86% to 100% in healthy dogs, 41% to100% in healthy cats, up to 82% in diseased dogs, and up to76% in affected cats. H. pylori infection is a worldwide, common, and lifelong infection (Crow et al., 2019). The Helicobacter species identified in gastritis and gastric ulcer pathogenic samples were incriminated as the inducing agents of gastric carcinoma in humans (Morgner et al. 2000). The degree of their colonization is not correlated the severity of gastritis in cats and dogs, although these bacteria were a predominant feature in the histopathology of the stomach (Ladeira et al. 2003).

Pigs, dogs, and cats constitute reservoir hosts for gastric Helicobacter species with zoonotic potential. Moreover, H. pylori is a zoonotic pathogen that has been suggested to be transmitted from companion animals to humans (Ladeira et al. 1994), as similar morphological patterns of bacteria were detected in animals and humans with gastritis (Bulck et al. 2005). However, the exact transmission route remains unknown and many studies have reinforced the transmission hypothesis of oro-oral or oro-fecal routes, as Helicobacter spp. were isolated from the mouth and feces of infected dogs and cats (Hu et al. 2017).

Some Helicobacter species are non-culturable and different techniques depend on cultured organisms for accurate diagnosis (Cattoli et al. 1999). Serological tests for veterinary application to detect Helicobacter species are not yet clinically available. The detection of fecal H pylori antigens is possible. PCR assay is a noninvasive, faster, simple, specific, and sensitive diagnostic test that will help recognize Helicobacter infection in humans and companion animals (Ford and Moayyedi, 2014).

The present investigation aimed at evaluating the incidence of Helicobacter spp. in companion animals and to assess their transmission role as a zoonotic risk.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Ethics approval

2.1.1 Animal ethics

Animal samples were obtained according to the principles of the Declaration of Egypt and approved by the Veterinary Medicine Cairo University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Ref; VETCU1022109045).

2.1.2 Human ethics

This study had full ethical approval from the Faculty of Medicine Ethics Committee based on the principles of the Declaration of Egypt.

2.2 Samples

Samples were collected from apparently healthy companion animals in the Cairo and Giza governorates. They included 70 dogs (30 serum samples, 30 feces samples, and 10 biopsies of gastric fundus fragments (∼5 mm)), 65 cats (30 serum samples, 30 feces samples, and five biopsies of gastric fundus fragments (∼3 mm)).

Seventy samples were collected from human patients who had been in contact with the companion animals under study and suffered from dyspepsia, chronic vomiting, and perforated peptic ulcer (30 serum samples, 30 stool samples, and 10 biopsies of gastric fundus fragments (∼5 mm)).

All samples were collected over the period of March 2016 to March 2019 and were examined for the presence of Helicobacter species.

2.3 Microbiological identification of Helicobacter species

Five grams of feces, stool, and biopsy samples were bacteriologically homogenized separately with 15 ml of Brucella broth (Sigma, USA) containing 20% glycerol (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) and 0.5 g of cholestyramine (Sigma, USA). A loop-full was streaked onto Columbia blood agar plates (Oxoid) supplemented with Helicobacter selective supplement (SR0147E, Oxoid). All plates were incubated under microaerophilic conditions at 37 °C for 3–5 days. Purified colonies underwent Gram staining for microscopic examination, followed by biotyping based on catalase production, oxidase production, urea hydrolysis, nitrate reduction, and salt tolerance (Forbes et al., 2007).

2.4 Serological analysis of Helicobacter pylori

Feces and stool samples were serologically analyzed for the presence of H. pylori antigens using Asan Easy Test H. pylori Ag (REF:24111, Korea), whereas serum samples were assessed for H. pylori antibodies using Asan Easy Test H. pylori Ab (REF:14131, Korea). The procedure and result reading were carried out according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.5 Molecular identification

DNA was extracted from samples using a modified QIAamp mini kit (Qiagen, Switzerland). A 25-μl PCR reaction containing 6 μl of template, 1 μl of each primer (20 pmol concentration), 12.5 μl of PCR Master Mix (Emerland, Japan), and 4.5 μl of deionized water was prepared and applied to a thermal cycler (Biometra, Germany). The sequence and thermal profile of each primer are listed in Table 1. The PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis (Sambrook et al. 1989) and a gel documentation system (Biometra BDA digital, Germany).

| Gene | Sequence | Amplified product | Thermal profile | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary denaturation | Secondary denaturation | Annealing | Extension | Cycles No. | Final extension | References | |||

| H. felis urea, ureB | GTG AAG CGA CTA AAG ATA AAC AAT | 241 bp | 94˚C/ 5 min. | 94˚C/ 30 sec. | 62˚C/ 30 sec. | 72˚C/ 30 sec. | 35 | 72˚C/ 7 min. | Camargo et al. 2003 |

| GCA CCA AAT CTA ATT CAT AAG AGC | |||||||||

| H. heilmannii ureB | GGG CGA TAA AGT GCG CTT G | 580 bp | 58˚C/ 40 sec. | 72˚C/ 45 sec. | 72˚C/ 10 min. | Arfaee et al. 2014 | |||

| CTG GTC AAT GAG AGC AGG | |||||||||

| H. pylori glmM | GGA TAA GCT TTT AGG GGT GTT AGG GG | 296 bp | 57˚C/ 40 sec. | 72˚C/ 45 sec. | 72˚C/ 10 min. | ||||

| GCT TAC TTT CTA ACA CTA ACG CGC | |||||||||

| Helicobacter spp. 16S rRNA | AAG GAT GAA GCT TCT AGC TTG CTA | 398 bp | 50˚C/ 40 sec. | 72˚C/ 40 sec. | 72˚C/ 10 min. | Tabrizi et al. 2015 | |||

| GTG CTT ATT CGT GAG ATA CCG TCA T | |||||||||

3 Results

3.1 Microbiological results

Twenty samples out of 115 feces, stool, and biopsy samples exhibited round, small, and translucent colonies at culture with an incidence of 17.4%. Gram staining showed the presence of Gram-negative, spiral, helical, or curved with blunt ends non-spore-forming microorganisms. The biochemical profile was positive for catalase, positive for oxidase, positive for urea hydrolysis, negative for nitrate reduction, and tolerant to 1.25% NaCl. The distribution of positive culture had a high prevalence in dogs (22.5% (9/40; 6 from feces and 3 from gastric biopsies)). The incidence in cats was 14.3% (5/35; 4 from feces and 1 from fundus biopsy), whereas the rate detected in humans was 15% (6/40; 3 from stool and 3 from fundus biopsy).

3.2 Serological result of Helicobacter pylori

Seventy serum samples had a positive antibody reaction using the Asan Easy Test H. pylori Ab. The dog serum exhibited a high prevalence (100%) of H. pylori, whereas the serum positivity in humans and cats was 83% (25/30) and 50% (15/30), respectively. A total of 58 H. pylori Ag were detected in feces and stool samples by Asan Easy Test H. pylori Ag. The rates of H. pylori Ag were 93% (28/30), 73% (22/30), and 26.6% (8/30) in dog feces, human stool, and cat feces, respectively.

3.3 Prevalence of Helicobacter species based on PCR

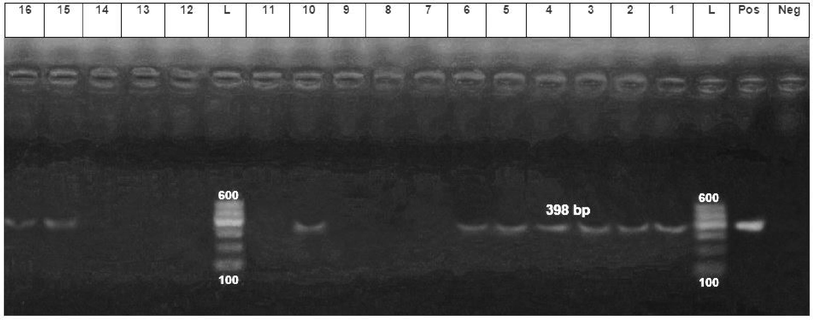

Fifty out of 115 samples (43.4%) exhibited an amplification band of 398 bp by PCR based on the 16S rRNA primer that was indicative of Helicobacter species (Fig. 1).

- PCR amplification from dogs, cats and human using 16S rRNA primer. The expected size of the product is 398 bp. Lanes: L, 100–600 bp DNA ladder; Neg, reagent control (no DNA); Pos, DNA extracted from a known positive dog feaces sample; 1–4, DNA extracted from dog feaces and gastric biopsy; ,5,6, DNA extracted from cat feaces and gastric biopsy and 10, 15, 16, DNA extracted from human stool and gastric biopsy.

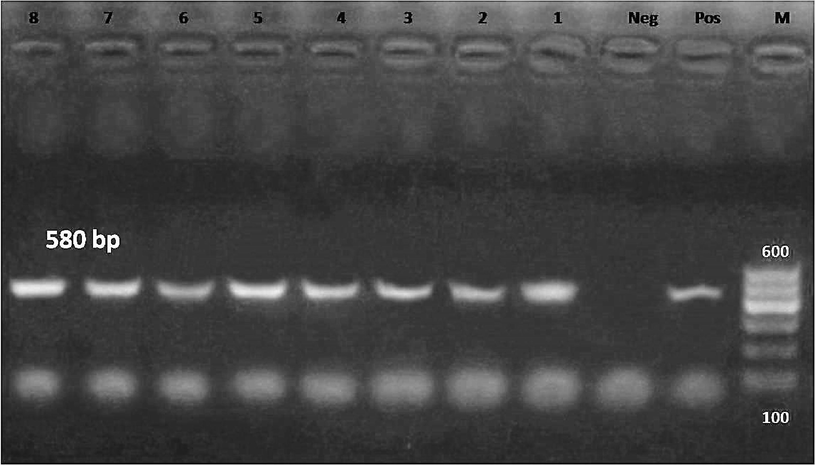

At the species level, and based on the primers listed in Table 1, H. heilmannii was more prevalent (amplification fragments at 580 bp), with a ratio of 16% (8/50). H. heilmannii was detected in four dog feces, one dog fundus, one human stool, one human fundus, and one cat fundus samples (Fig. 2).

- PCR amplification using H. heilmannii ureB primer. The expected size of the product is 580 bp. Lanes: L, 100–600 bp DNA ladder; Pos, DNA extracted from a known positive dog feaces sample; Neg, reagent control (no DNA); 1–4, DNA extracted from dog feaces and 5, from dog fundus biopsy; 6, DNA extracted from human stool; 7, DNA extracted from fundus biopsy; 8, DNA extracted from cat fundus biopsy.

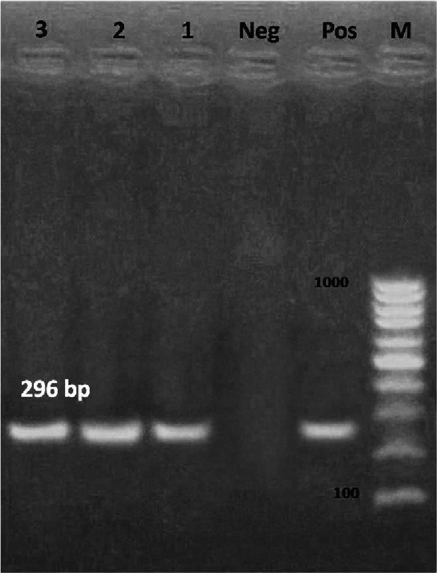

Three DNA samples yielded a positive amplified fragments at 296 bp corresponding to H. pylori based on the H. pylori glmM primer, with a prevalence of 6% (3/50); two from human fundus and one from dog fundus biopsies (Fig. 3). All samples were negative for H. felis. Different unidentified Helicobacter species were detectable with an incidence of 78% (39/50), which warrants further investigation.

- PCR amplification using H. pylori glmM primer. The expected size of the product is 296 bp. Lanes: L, 100–1000 bp DNA ladder; Pos, DNA extracted from a known positive dog feaces sample; Neg, reagent control (no DNA); 1, DNA extracted from dog fundus biopsy; 2, 3 DNA extracted from human fundus biopsy.

4 Discussion

Helicobacter infection is a worldwide zoonotic infection. The incidence of Helicobacter infection is very high in Egypt and is attributed mainly to H. pylori (Hooi et al. 2017). Helicobacter spp. can attack the mucosa of the gastrointestinal tract in humans, wild animals (such as monkeys), and domestic animals (Abdi et al., 2014; Hong et al., 2015). The present investigation detected different Helicobacter spp. in companion animals (dogs and cats) in correlation to zoonotic and public health repertoires. We collected 205 samples from apparently healthy companion animals and human patients who suffered from gastrointestinal disturbances and had been in contact with the animals sampled in the Cairo and Giza governorates. All collected samples were similar to those reported previously, including feces, serum, and fundus biopsies from companion animals, as well as human stool and fundus biopsies (Hu et al. 2017).

The diagnostic methods for gastric Helicobacter species have been classified as noninvasive or invasive. The noninvasive methods include the detection of bacteria, serologic methods, urea breath test, and bacterial DNA test. The invasive methods include gastric biopsy specimens or brush cytology, histological examination, electron microscopy, urease test, PCR, and in situ hybridization (ISH) (Jankowski et al. 2016). The present work revealed a culture prevalence of 17.4% in 115 different samples, with a biochemical profile that was positive for catalase, positive for oxidase, positive for urea hydrolysis, negative for nitrate reduction, and tolerant to 1.25% NaCl, which confirmed the non-culturable results of some Helicobacter species (Okubo et al. 2017).

Serodetection of H. pylori antigens or antibodies is common in human laboratory analyses, and seroconversion does not correlate with the degree of inflammation or colonization density (Shinozaki et al., 2002). Serologic tests for helicobacteriosis in a veterinary setting are not yet clinically available. The detection of fecal H pylori antigens, although possible, has not been adapted for use in veterinary patients. The present study revealed a high detection rate of both H. pylori antigens and antibodies in dog feces, followed by human stool and cat feces. The sensitivity and specificity of stool antigen testing for H. pylori typically exceed 92%, whereas H. pylori IgG serologic testing has a specificity of less than 80% and cross reaction may occur (Crow et al., 2019).

The pathogenesis and therapeutic questions regarding Helicobacter species require a simple, sensitive, noninvasive, and readily available specific diagnostic test. PCR analysis would allow Helicobacter documentation in dog and cat feces and human stool, as well as in human and animal biopsies (Shinozaki et al., 2002). The authors investigated Helicobacter species in dog and cat feces and human stool using PCR of H. heilmannii ureB, H. felis ureB, and H. pylori glmM (against 16S rRNA), with amplification of fragments of 398, 580, 241, and 296 bp, respectively. The rate of detection of Helicobacter species was 43.4%. Moreover, H. heilmannii was identified in 16% and H. pylori was identified in 6% of samples. The detection of H. heilmannii in human samples and the presence of H. pylori in companion animals (dogs and cats) suggest that those animals act as reservoirs of Helicobacter species; some studies have suggested that animals are natural hosts of these species. This implies that H. pylori is present in the stomach mucosa with a mild or absent inflammatory response (Hatakeyama, 2014). Moreover, these results support the importance of dogs and cats in the transmission of Helicobacter species to humans, especially to the patients who were in contact with the companion animals under investigation. Many authors documented this theory of zoonotic and public health hazard but did not explain the mode of transmission; they only suggested oral or oro-fecal transmission (Shinozaki et al., 2002; Crow et al., 2019).

All samples were H. felis negative, and 78% of Helicobacter species were unidentified, which warrants further investigation. Gastric Helicobacter infections are present in both apparently healthy dogs and dogs presenting with clinical gastric disease, based on many studies (Shinozaki et al., 2002; Saleh et al., 2020).

5 Conclusion

This study confirmed that the serological technique is a screening test, and that PCR is a reliable, sensitive, and diagnostic test for the detection of Helicobacter species. Companion animals, including dogs and cats, play a major source as a zoonotic and public health hazard. Finally, dogs and cats act as reservoirs with mild or no clinical signs.

Acknowledgment

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Saud University for supporting the work through the research group project No.: (RG-162).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Detection of Helicobacter spp. DNA in the colonic biopsies of stray dogs: molecular and histopathological investigation. Diagn. Pathol.. 2014;9:50.

- [Google Scholar]

- PCR-based diagnosis of Helicobacter species in the gastric and oral samples of stray dogs. Comp. Clin. Pathol.. 2014;23:135-139.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sulleghiandoletubulari del tubogastroenterico e sui rapporti del lorocol Pepiteliodi rivestimentodella mucosa. Arch. MikrAnat.. 1893;42:82.

- [Google Scholar]

- Identification of non-Helicobacter pylori spiral organisms in gastric samples from humans, dogs, and Cats. J. Clin. Microbiol.. 2005;43:2256-2260.

- [Google Scholar]

- Use of polymerase chain reaction and enzymatic cleavage in the identification of Helicobacter spp. in gastric mucosa of human beings from North Paraná, Brazil. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 2003;98:265-268.

- [Google Scholar]

- Occurrence and characterization of gastric Helicobacter spp. in naturally infected dogs. Vet. Microbiol.. 1999;70:239-250.

- [Google Scholar]

- Forbes, B.A., Sahm, D.F., Weissfeld, A.S., 2007. Bailey & Scott’s Diagnostic Microbiology. (Mosby-Elsevier 2007).

- Helicobacter pylori cagA and gastric cancer: a paradigm for hit-and-run carcinogenesis. Cell Host Microbe.. 2014;15:306-316.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of three diagnostic assays for the identification of Helicobacter spp. in laboratory dogs. Lab. Anim. Res.. 2015;31:86-92.

- [Google Scholar]

- Global Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology.. 2017;153:420-429.

- [Google Scholar]

- Systematic review with metaanalysis: the global recurrence rate of Helicobacter pylori. Aliment Pharmacol. Ther.. 2017;46:773-779.

- [Google Scholar]

- Detection of gastric Helicobacter spp. in stool samples of dogs with gastritis. Pol. J. Vet. Sci.. 2016;19:237-243.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ultrastructure of a spiraled microorganism in the gastric mucosa of dogs. Am. J. Vet. Res.. 1970;31:1453-1461.

- [Google Scholar]

- Helicobacter heilmannii- associated primary gastric low-grade MALT lymphoma: complete remission after curing the infection. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:821-828.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of Helicobacter spp. in dogs from Campo Grande-MS. Cienc. Anim. Bras Goiânia. 2017;18:1-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Helicobacter-species classification and identification. Br. Med. Bull.. 1998;54:17-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Rappin, J., 1958. Contribution á l'étude des bactéries de la bouche á létat normal et dans la fièvre typhoide. Ph.D Thesis, Collège de France, Nantes, 1881. Ref. Am. J. Vet. Res. 19, 677–680.

- Increased production of matrix metalloproteinases in Helicobacter pylori infection that stimulates gastric cancer stem cells. Int. J. Vet. Sci.. 2020;9:355-360.

- [Google Scholar]

- Salomon, H., 1896. Ueber das Spirillum des Säugetiermagens und sein Verhalten zu den Belegzellen. Zentralbl. Bakteriol. Parasitenkd. Infectionskrankh. 1. Abt. 19, 433–442.

- Molecular coloning. A laboratory manual.Vol!. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratotry Press; 1989.

- Fecal polymerase chain reaction with 16S ribosomal RNA primers can detect the presence of gastrointestinal Helicobacter in dogs. J. Vet. Intern. Med.. 2002;16:426-432.

- [Google Scholar]

- Identification of Helicobacter spp. in gastrointestinal tract, pancreas and hepatobiliary system of stray cats. Iran J. Vet. Res.. 2015;16:374-376.

- [Google Scholar]