Zinc based iron mixed oxide catalyst for biodiesel production from Entermorpha intestinalis, Caulerpa racemosa and Hypnea musicoformisis and antibiofilm analysis using leftover catalyst after transesterification

⁎Corresponding author. arunalacha@gmail.com (A. Arun)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

The focus of this study is to produce zinc-based iron oxide nanocomposite as a catalyst for biodiesel and antibiofilm applications, which were characterized by using X-ray diffraction (XRD) and Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FE-SEM). The nanocomposite was evaluated as a catalyst for biodiesel production by using lipid extracted from Entermorpha intestinalis, Caulerpa racemosa, and Hypnea musicoformisis. All were highly yielding saturated, monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids. Traditional transesterification methods have proven in alcoholysis with methanol yields reasonably in the presence of a heterogeneous catalyst. Moreover, heterogeneous catalyst exhibits potential conversion in the reaction and having reliable reusability. The presence of metal ions from zinc oxides exhibits from the catalyst minimized the course of the reaction. H. musicoformisis shown the topmost conversion of 78% and C. racemosa, E. intestinalis shows reliable conversions of 72% and 70.5%, respectively. In the optimization of different parameters. The methyl ester presence was determined by FT-IR and GCMS analysis. In reusability aspects, we utilized Fe2ZnO4 composite after transesterification for antibiofilm analysis also. The results indicate that leftover nanoparticles have strong antibiofilm properties and could be applied as an efficient osteoconductive functional material.

Keywords

Entermorpha intestinalis

Caulerpa racemosa

Hypnea musicoformisis

Fe2ZnO4

Antibiofilm

1 Introduction

The major concern of research, development, and commercialization are turned towards algal oil (lipid) products having properties in nutraceutical fields, good alternation of fish oils, industrial chemical feedstock, the main biofuels production emphasis through transesterification process (Gosch et al., 2012; Sivaprakash et al., 2019). Biodiesel overcomes the general environmental issues like less carbon monoxide, Food demand, life span, lower yield, higher utilization are some limitations for using such oils as a fossil fuel alternation (Mata et al., 2010). Researches nowadays focus on marine products for biofuel production (Singh and Gu, 2010; Williams and Laurens, 2010) because of enriching lipid contents, renewable in nature, large scale production compatibility and environmental friendly (Carvalho et al., 2011). Seaweeds are having to attract properties with potential bioactive components that exhibit applications in pharmaceutical, biomedical, nutraceutical fields & food preparations (Kumar et al., 2008; Veena et al., 2007). Many seaweed species are having more than 10% of lipid content in dry weight, which can predominantly be used for the production of oil-based products (Gosch et al., 2012). P. kumara (2010) et al. revealed the vital importance of health, nutrition from Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) where get from 27 macroalgal species that produce both lipid and fatty acids (Kumari et al., 2010). Fatty acid methyl esters are called biodiesel, derived from triglycerides via the transesterification process by adding methanol and getting glycerol as a by-product (Singh and Singh, 2010). The essential need of transesterification in vegetable oil is increasing volatility and reducing viscosity because direct usage with highly viscous poses some embarrassment in engines (Ryan et al., 1984; Xie and Li, 2006). From fatty acid methyl esters, the main products of long-chain carboxylic acids, alternative diesel oils, detergents, mono, di, and triglycerides were manufactured commercially (Ahn et al., 1995; Mazzocchia et al., 2004). Biodiesel efficiency is based on physical and chemical properties, and it should be similar to petroleum-derived diesel (Shuit et al., 2013). The cost of biodiesel (depends upon using raw material and processing) is still high than petroleum diesel (Ma and Hanna, 1999). The cost issue would be reduced by using unutilized raw materials (like seaweed), simple processing techniques, and waste utilization (Bournay et al., 2005; Demirbas, 2007; Huber et al., 2006). Commercially used homogenous catalysts (H2SO4, HCl, NaOH, or KOH) (Taufiq-Yap et al., 2011), yields very less, because of the base catalyst consumption during saponification and in case of the acid catalyst leads to corrosion in engines(Baskar et al., 2017). The solid heterogeneous catalyst introduction in biodiesel production could decrease cost and effective replacement for diesel, which leads to financial benefits(Sivaprakash et al., 2019). Transesterification using heterogeneous catalytic system is considered as a green technology, because of attracting properties such as reusability(Suppes et al., 2004), least wastewater excretion (Chouhan and Sarma, 2011), simple separation of glycerol and biodiesel (Chouhan, and Sarma, 2011; Lee and Saka, 2010). Currently, heterogeneous catalyst research focusing on sulfated zirconia (Kansedo and Lee, 2012; Rattanaphra et al., 2012), Zr-SBA-15 (Iglesias et al., 2011), carboxylic zinc salts, Fe2O3-doped sulfated tin oxide, and sulfated iron-tin mixed oxide. In those metallic components, we focus on Fe2ZnO4 because of iron oxide (magnetic), which exhibits high activity in transesterification (Zhai et al., 2011); moreover, it has high adsorption for carboxylic acids, including FFA (Cano et al., 2012). The plain ZnO has some constraint, and it would be solved by adding some metals (Mn, Ni, Fe, Co, Cr), which deserves several applications because of the least particle size and enhancement in basicity, surface area. Amphoteric oxide, like ZnO, performs good transesterification of free fatty acids in both acid-base sites of by functional system (Peterson and Scarrah, 1984). The fatty acid chain X-3 PUFAs, as eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosa-hexenoic (DHA) are present in several seaweed species (Kumari et al., 2010) which are easy to harvesting & cultivation, moreover having several nutritional benefits (Ginzberg et al., 2000). Antibiofilm effects of metal coated ZnO were reported recently (Morsi et al., 2016). This motivated us to do efficient reusability of Fe2ZnO4 nanocomposite it tested as an antibiofilm agent against bacterial pathogens.

With this background, the present work aimed to produce biodiesel from E. intestinalis C. racemosa & H. musicoformisis through the transesterification process by using Fe2ZnO4 as a heterogeneous catalyst. The reaction parameters of oil molar ratio, catalysts concentration, temperature, and time were fully optimized to get the best biodiesel yield. FT-IR & Gas chromatography analysis characterized the biodiesel. The remaining catalyst after transesterification was tested to found antibiofilm efficiency against ATCC stains.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

Ferric chloride, Zinc chloride, Potassium ferricyanide were the chemicals used for the synthesis of Fe2ZnO4 nanocomposite, and methanol applied for biodiesel production was purchased from SRL chemicals, India. All the chemicals applied for the synthesis were the analytical grade used without any further purification. The seaweed species E. intestinalis C. racemosa & H. musicoformisis were originally collected from Mandapam coastal area (78° 8′ E, 9° 17′ N), India. After collection, they were thoroughly cleaned to remove epiphytes and were dried under shade.

2.2 Lipid extraction

For the complete lipid extraction, we applied the AFNOR (1983) method (Guillot et al., 1983). 4 g of ground algal powder was homogenized with 15 ml of (1:2 ratio) formic acid and HCl. This mixer was heated for 20 mins at 70 °C. After attaining room temperature, 30 ml of chloroform and ethanol (1:2) were mixed vigorously for 30 mins in stirrer. All the extracts were filtered, and organic phases were collected then evaporated in a rotary evaporator at 60 °C. The collected total lipid content was determined gravimetrically.

2.3 Synthesis of Fe2ZnO4 catalyst

Ferric chloride and zinc chloride are the precursors used in the synthesis, equal ratio (1:1) of ferric chloride and zinc chloride were dissolved in distilled water then mixer was subsequently stirred. Above this solution, the same volume of potassium ferricyanide was added dropwise to form the Iron zinc hexacyanoferrate complex. After that formation, 100 ml of 1 M NaOH solution was added dropwise to break the hexacyanoferrate complex to get precipitate.

2.4 Characterization of catalyst and biodiesel

Synthesized Fe2ZnO4 was characterized by X-ray diffraction (XRD) to found the phase identification of crystalline structure by using X’Pert Pro analytical diffractometer, Japan, using monochromatic nickel-filtered Cu Ka radiation (k = 0.15405 nm). Diffractograms have recorded the ranges between (4° and 90°), and the generator runs at 40 kV and 30 mA. In order to find the magnetic measurements of Fe2ZnO4 nanocomposite, we used Quantum design MPMS SQUID Magnetometer and a Vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM).

2.5 Characterization of biodiesel

Gas chromatography analysis was recorded by Shimadzu 2014, Japan) equipped with flame ionization detector (FID) and capillary column 105 m, 0.32 mm ID, 0.20 μm film thicknesses) with a carrier gas of Nitrogen. The injector, column, detector temperature maintained at 220 °C, 100 °C and 250 °C respectively. 1 μl of the FAME sample was injected in split mode (35:1) at a flow rate of 27.8 ml/min. The capillary column length was calculated as 105 M and the total run time was 70 min. GC solution software was applied to analyze peak areas of FAME with internal standards. The major physiochemical properties of biodiesel were consists of Saponification value, Iodine value, acid value, higher heating value, cetane number, water content, sulfated ash and density were analyzed by ASTM standards.

2.6 Experimental setup of transesterification and optimization

Transesterification reaction was conducted using a three-neck round bottom flask fixed with a reflux container fixed on an oil bath above the magnetic stirrer. The reaction was started by mixing the required amount of methanol and seaweed lipids. Above the appropriate mixer amount of catalyst was added, and the desired temperature was maintained. The reflux container used to recollect the evaporated methanol from the mixer.

2.7 Antibiofilm assay against biofilm-forming bacteria

2.7.1 Selection of biofilm-forming bacterial strains

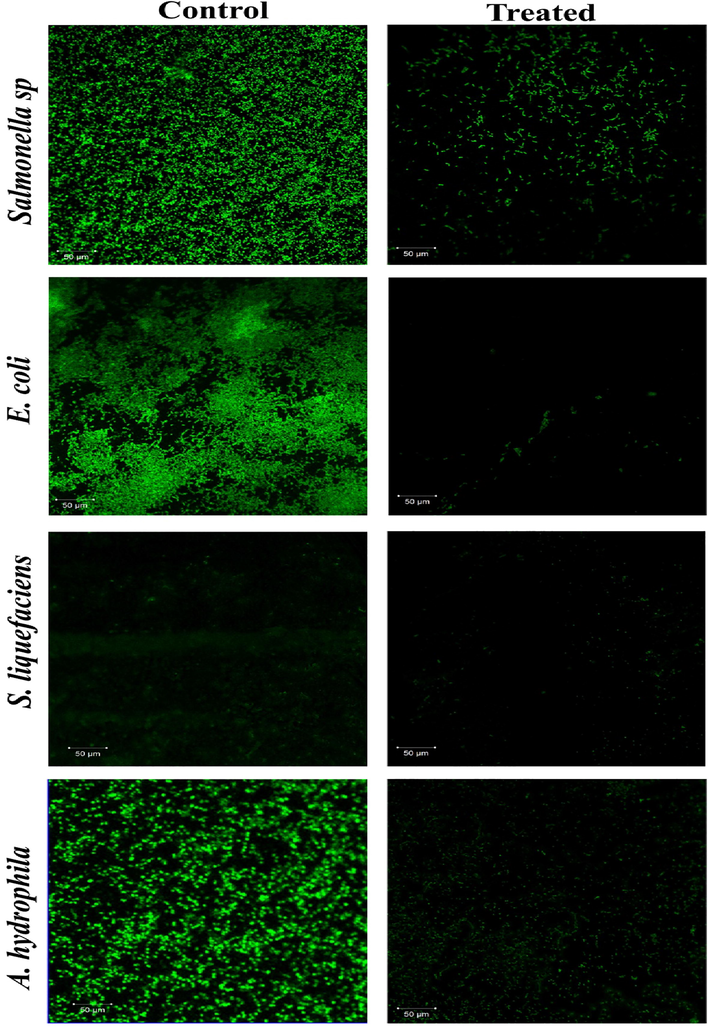

Biofilm forming four different microbial strains such as Salmonella sp. (JN596113), E. coli (JN585664), S. liquefaciens (JN596115), and A. hydrophila (JN561697), were used to study the antibiofilm analysis of remaining Fe2ZnO4 after transesterification.

2.7.2 Confocal laser Scanning microscopic (CLSM) analysis

As reported by Nithya et al., 2010, the CLSM analysis of Fe2ZnO4 has been performed and recorded.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Characterisation of zinc iron oxide nanocatalyst

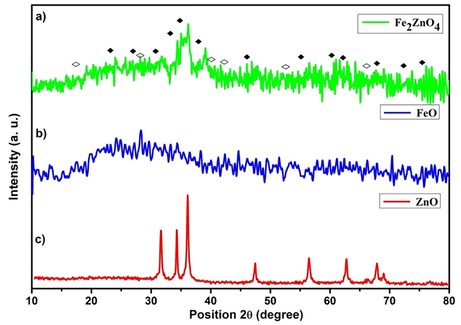

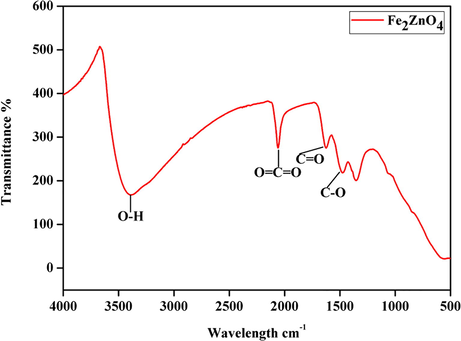

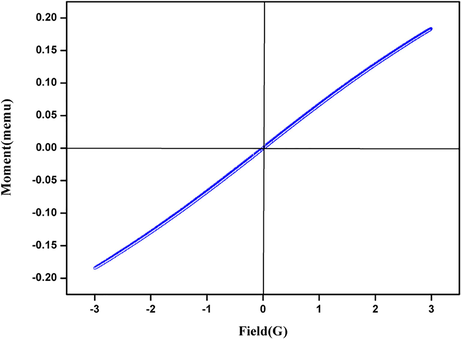

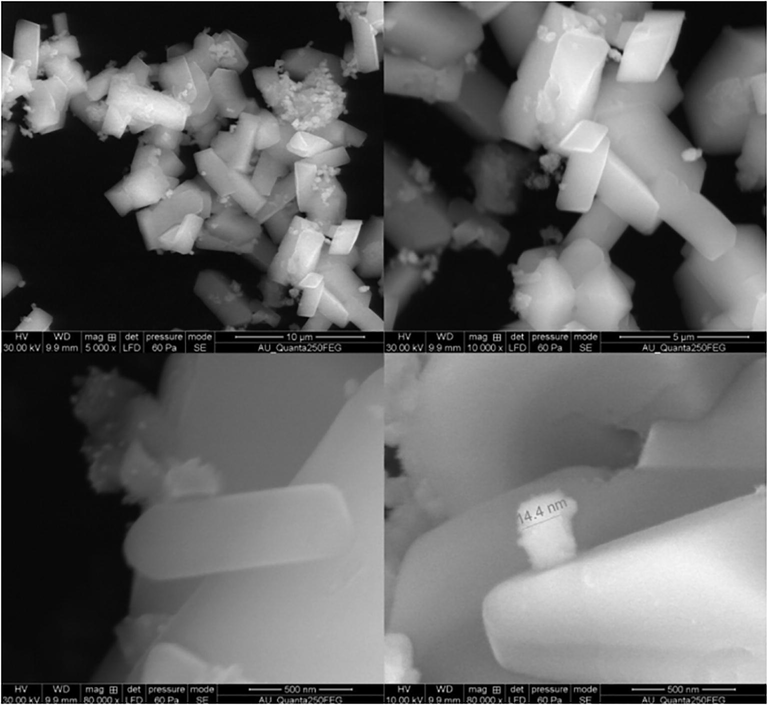

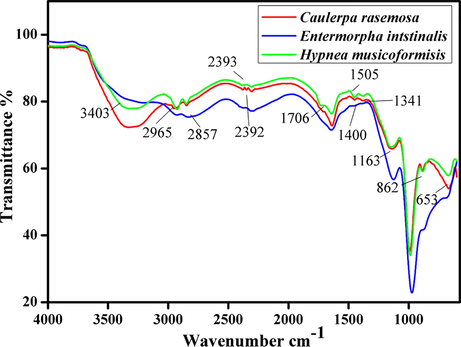

We have prepared a nanomagnetic solid Fe2ZnO4 catalyst by a simple co-precipitation method and were probed by structural characterizations with powder XRD, FT-IR, VSM, and TEM. In XRD, results show a clear nanocrystalline phase was achieved without any segregated impurity Fig. 1. The sample was noted as a polycrystalline material and minor peaks from Fe2ZnO4 are indicated in the figure. The profile fitting of the data was performed by XPert high score plus. The diffraction has a good agreement for Fe2ZnO4 (ICDD: 01-079-1150) moreover, some peaks observed in diffractogram for Fe2ZnO4 related to cubic and hexagonal structure. The XRD results confirm that Iron is perfectly encapsulated with ZnO. Some reports stated that increasing the quantity of ZnO precursors will lead to an impact in XRD intensity. FTIR spectroscopy gives detail information about the presented functional groups in the catalyst. We noted the peaks similarity obtained over the transmittance and vibration mode (Lippincott, 1963). Fig. 2 clearly shows the peaks obtained at the range of 3500 cm−1 is O–H. The vibration mode between 1400 and 2300 cm−1 peaks were obtained C=O, C–H, C-O. The observation of the magnetic mechanism in the nanocrystalline system has been criticized due to the surface volume ratio leads to the behavior of individual atomic moments. The magnetic property of the Fe2ZnO4 was analyzed by VSM. Fig. 3 indicates the magnetic moment at the different magnetic fields. The higher concentration of Fe precursors leads to the impact of magnetic property in the catalyst (Saleh et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2008). FE-SEM image (Fig. 4) of Fe2ZnO4 shows broad particle size distribution with size ranging from 14 to 50 nm. The micrograph reveals that all the nanoparticles are single crystalline does not affect any lattice inadequacy.

- X-ray diffractogram of Fe2ZnO4 nanocomposite.

- FT-IR spectrum of Fe2ZnO4 nanocomposite.

- VSM analysis of Fe2ZnO4 nanocomposite.

- Morphological characterizations by FE-SEM Fe2ZnO4 nanocomposite.

3.2 Optimisation parameters applied for FAME

3.2.1 Effect of catalyst concentration

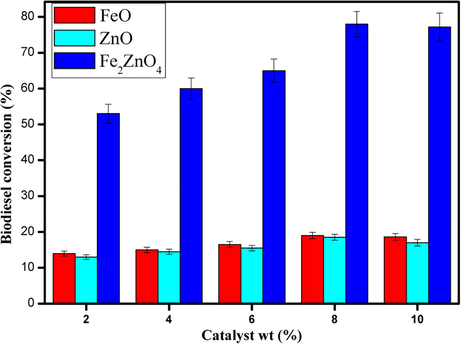

Catalyst concentration is the primary factor force towards significant yield, which induces the reaction rate and affects directly in transesterification (Baskar et al., 2017). Generally, the surface of nano zinc oxide owing primary site, which makes the efficient conversion in biodiesel (Baskar and Soumiya, 2016). Doping of Fe2O3 on zinc can ameliorate catalytic activity because of the presence of a large number of active acid sites. In Fe2ZnO4 we can get both acid sites and basic sites, which enhance the catalytic performance in transesterification. Fig. 5 shows the evolution (2–10 wt%) of catalytic activity in transesterification with a 1:13 ratio of methanol: oil, 80 °C of the reaction temperature in 80 mins of reaction time. The maximum conversion was achieved at 8 wt% of catalyst Fe2ZnO4 catalyst, and we checked the plain FeO and ZnO, which exhibits less conversion. Moreover, the further increment of the catalyst leads to a slight reduction in conversion which caused by slurry formation(Jagadale et al., 2012).

- Effect of Fe, ZnO and Fe2ZnO4 nanocomposite concentration on biodiesel yield.

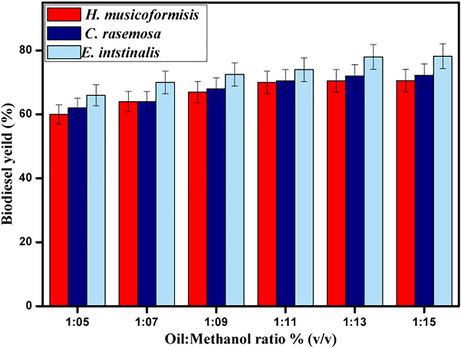

3.2.2 Effect of oil to methanol ratio

The continues process of biodiesel production leads to the reaction reversible; it would be subsequent towards culmination by adding an excess amount of alcohol (Talebian-Kiakalaieh et al., 2013). Simultaneously biodiesel yield would be favor by adding an excess amount of methanol (Wu et al., 2012) because of increasing good contact between reactants (Maceiras et al., 2011). It can be seen from Fig. 6 simultaneous yields of biodiesel while increasing oil to methanol ratio from 1:5–1:15 %w/v. The high yield of 78% for H. musicoformisis was reached when oil to methanol ratio is close to 1:13, which was higher yield by comparing (Maceiras et al., 2011) with applying similar oil to methanol ratio. C. racemosa & E. intestinalis seaweed extracts achieved 72.5%, 70%, respectively. The constant reaction parameters were maintained at 80 °C temperature, 80 mins of reaction time, and 8 wt% of catalyst. However, Fig. 6 shows beyond the excessive amount of methanol increase the yield, moreover adding methanol after attaining higher yield cause issues in separation and purification(Wu et al., 2012). From the optimization of stoichiometric values, we determined that 1:13 oil to methanol ratio delivers the highest yield in all seaweeds, and additional methanol decreases yield due to the accumulation of methanol (Baskar and Soumiya, 2016). Additionally, it would be essential to varying other parameters reaction temperature and time to improve topmost yield.

- Effect of oil-methanol ratio on biodiesel yield by Fe2ZnO4 nanocomposite.

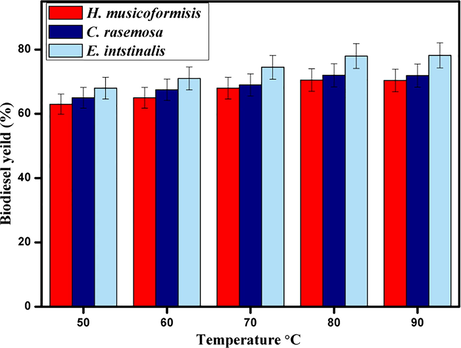

3.2.3 Effect of reaction temperature

Reaction temperature deals considerable influence in biodiesel production because limited temperature must be given in reaction for methanol to attain atmospheric pressure (Zhao et al., 2013). High temperature enhances the solubility of solvents, which tends to increase the diffusion rate (Baskar and Soumiya, 2016). All experiments were carried out for 80 mins of reaction time, with 8 wt% of catalyst and 1:13 oil to methanol ratio. Fig. 7 shows an increment of yield at different temperatures. From the results, we can able to decide that the lower temperature deserves less yield. Biodiesel conversion was achieved at 78% in H. musicoformisis 80 °C, and the rest of the species shows similar results for the same temperature. Further increment in temperature causes fewer yields due to significant methanol loss.

- Effect of reaction temperature on biodiesel yield by Fe2ZnO4 nanocomposite.

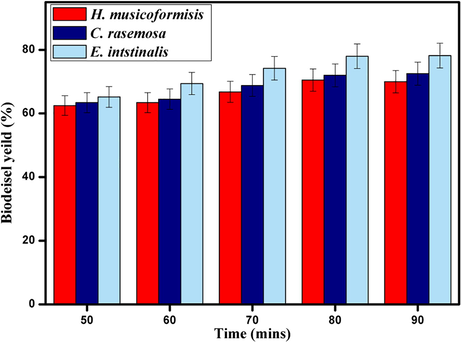

3.2.4 Effect of reaction time

Methyl ester content in macroalgae is low; to manage this issue, reaction time optimization is needed (Maceiras et al., 2011). Moreover, in the case of nano catalytic conversion, methyl ester yield is directly proportional to reaction time (Baskar et al., 2017). All the experiments in reaction time optimization were conducted in the same reaction conditions, 1:13 oil to methanol ratio, 8 wt% of catalyst and 80 °C of reaction temperature. From different parameters, Fig. 8 indicates 80 mins of reaction time is enough for maximum yield of 78% in H. musicoformisis and after it stays practically constant. Moreover, the reaction was carried out by varying temperatures to find a linear relationship between reaction temperature and time.

- Effect of reaction time on biodiesel yield by Fe2ZnO4 nanocomposite.

3.2.5 Effect of reusability of the catalyst

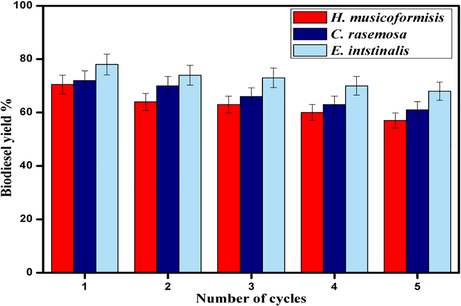

According to find the stability and efficiency of catalyst reusability is a significant feature after transesterification. Separation and simple purification are necessary for nanocatalyst to regenerate in transesterification under the same parameters. The activity of the catalyst reveals from Fig. 9, which tends stability of the catalyst, is similar to the initial yield after five cycles. Whether the yield was decreased because of the performance of the active site might be reduced.

- Reusability of Fe2ZnO4 Nanocomposite for biodiesel yield.

3.3 Characterisation of biodiesel E. intestinalis, C. Racemosa & H. Musicoformisis

3.3.1 FT-IR characterization of FAME

FT-IR spectra biodiesel was measured in the mid-infrared region between 400 and 4000 cm−1 for identifying the functional properties of corresponding bands with different stretching and bending vibrations. The major spectrum of FAME discrimination appears in the range between 1500 and 900 cm−1 and which mentioned as the fingerprint region (Rabelo et al., 2015). FT-IR spectra of E. intestinalis, C. racemosa & H. musicoformisis species were observed with similar variations in Fig. 10. The respective bands were assigned with basic biochemical standards (Stehfest et al., 2005). Carbonyl group presence in FT-IR data was to determine the substituent effects and structure of the molecule. In methyl ester characterization, two active absorption bands were shown from carbonyl (ʋC=O) around 1750–1730 cm−1, moreover C–O stretching. The primary band lipids and fatty acids were associated with (ʋC=O) ester groups found at ∼1740 cm−1(Dean et al., 2010).

- FT-IR analysis of biodiesel produced form Entermorpha intstinalis, Caulerpa racemosa & Hypnea musicoformisis.

3.3.2 FAME characterisation by Gas chromatography mass spectroscopy

Extracted lipid was quantified and tabulated (Table 1). To know the fatty acid profiling, all the lipid classes were quantified, and most of the samples contain saturated, monounsaturated and polyunsaturated between C-8 to C-24 methyl esters (Table 2). Total saturated fatty acids (SFA) determined by GCMS for E. intestinalis (14.93%), C. racemosa (32.47%), and H. musicoformisis (52.56) of total FAMEs. In saturated fatty acids, the most bounded profile was noted as palmitic acid (C16:0). A considerable amount of myristic acid (C14:0) was detected range from 4.53% to 18.17% for C. racemosa, H. musicoformisis, and absent in E. intestinalis (See Table 3).

| Algae Classification | Algae | (mg/g fr.wt) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dry weight | Total lipid fraction (Afnor (1983) method) | Maximum FAME Conversion (after optimisation) (%) | ||

| Green (chlorophycea) | Enteromorpha intestinalis | 20.5 ± 0.6 | 8.5 ± 0.6 | 70.5% |

| Caulerpa racemosa | 15 ± 0.8 | 7.4 ± 0.4 | 72% | |

| Red (Rhodophyceae) | Hypnea musciformis | 7 ± 0.2 | 4.4 ± 0.3 | 78% |

Values are means of maximum 5 replicates ± standard deviation at 95% confidence interval

| Fatty acid | E. intstinalis | C. racemosa | H. musicoformisis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Butyric acid (C4:0) | – | 4.53% | 2.8453% |

| Caprylic acid (C8:0) | 7.648% | 12.53% | 8.7011% |

| Myristic acid (C14:0) | – | 8.7011% | 3.19% |

| Pentadecanoic acid (C15:0) | – | 18.17% | 6.941% |

| Palmitic acid (C16:0) | 7.8011% | 3.941% | 44.7234% |

| Heptadecanoic acid (C17:0) | 28.32% | – | 3.5921% |

| Octadecenoic(C18:1) | – | 55.5921% | 2.4543% |

| Hexadecenoic(C16:1) | – | 6.941% | 15.4% |

| Eicosapentenoic acid(C20:4) | 55.5921% | 7.43% | 3.32% |

| Stearidonic acid (C18:4x3) | – | 2.39% | 8.79% |

| Linoleic acid (C18:2) | – | 4.45% | 2.8453% |

| Total Saturated fatty acid | 55.6% | 67.8% | 72.98% |

| Monounsaturated fatty acid | 43.4% | 27.3% | 17.78% |

| Polyunsaturated fatty acid | 1.32% | 5.2% | 8.94% |

| Parameters of Extracted algal oil | Enteromorpha intestinalis | Caulerpa racemosa | Hypnea musciformis | Units |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average molecular weight | 780 | 780 | 780 | g/mol |

| Saponification value | 175 | 180 | 190 | ml of H3PO4 /g |

| Iodine value | 88 | 87 | 89 | – |

| Acid value | 13 | 14 | 12 | ml of H3PO4/g |

| Higher Heating Value | 24.4 | 12.6 | 37.4 | (MJ/Kg) |

| Cetane number | 33.2 | 45.4 | 66.3 | |

| Water content | 3.4 | 3.3 | 3.2 | %/ml |

| Sulphated ash | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.006 | %/ml |

| Density | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.84 | %/ml |

| Average molecular weight | 780 | 780 | 780 | g/mol |

| Saponification value | 175 | 180 | 190 | ml of H3PO4 /g |

| Iodine value | 88 | 87 | 89 | – |

| Acid value | 13 | 14 | 12 | ml of H3PO4/g |

3.4 Antibiofilm activity of metal oxide nanoparticles after transesterification

The strong dense of biofilm formation was noticed on the control glass pieces (Fig. 11). Thus, AgNps were highly active against the adherence of strains, and biofilm formations were proven by the CLSM study (Martinez-Gutierrez et al., 2013). Shrestha et al. (2010)stated that CS-Np and ZnO-Np composite's own consequent antibiofilm property ruptured the multilayered, 3-dimensional biofilm architecture of bacterial pathogens. Vinoj et al., 2013)demonstrated that biofilm formation by B. licheniformis and V. parahaemolyticus were entirely disrupted by the CS/ZnO composite from 40 mg/ml and 60 mg/ml concentrations, respectively. It also examined that protein stabilized AgNPs coated surface of polycaprolactam has enhanced the antifouling activity against the pathogens (Prabhawathi et al., 2012; Al-Dhabi et al., 2018; Al-Dhabi et al., 2019). In our findings, the results of CLSM supported the antibiofilm property, and Fe2ZnO4 was a remarkably higher potential antifouling agent against biofilm-forming strains.

- Visualization of bacterial biofilm inhibition of Fe2ZnO4 nanocomposite by CLSM.

4 Conclusion

Fe2ZnO4 catalysts had shown a compelling performance in transesterification of E. intestinalis, C. racemosa & H. Musicoformisis lipids. Fe2ZnO4 shows a broad spectrum in X-ray diffraction analysis and exhibits the particle size distribution with size ranging from 14 to 50 nm. From the FT-IR spectrum and Gas chromatography analysis, we found the different ratios of saturated, monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids. In the reusability aspect, the Fe2ZnO4 composite effectively controlled the biofilm growth of bacterial strains. Thus, we conclude that the Fe2ZnO4 composite is suitable for biodiesel production from H. Musicoformisis and a successful antibiofilm agent.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Department of Science and Technology-Promotion of University Research and Scientific Excellence (DST-PURSE) [DST letter No.SR/PURSE phase 2/38(G), dt.21.02.2017], India; RUSA – Phase 2.0 grant [Letter No. F.24-51/2014-U, Policy (TN Multi-Gen), Dept. of Edn. Govt. of India, Dt. 09.10.2018]; Scheme for Promotion of Academic and Research Collaboration (SPARC) (No. SPARC/2018-2019/P485/SL; Dated: 15.03.2019) and University Science Instrumentation Centre (USIC), Alagappa University, Karaikudi, Tamil Nadu, India. The authors extend their appreciation to The Researchers supporting project number (RSP-2019/108) King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The authors are also grateful for the collaborative research conducted by the institutes and universities.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Green biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles produced from marine Streptomyces sp. Al-Dhabi-89 and their potential applications against wound infection and drug resistant clinical pathogens. J. Photochem. Photobiol., B 2019111529

- [Google Scholar]

- Environmental friendly synthesis of silver nanomaterials from the promising Streptomyces parvus strain Al-Dhabi-91 recovered from the Saudi Arabian marine regions for antimicrobial and antioxidant properties. J. Photochem. Photobiol B. 2018;189:176-184.

- [Google Scholar]

- A Low-Waste Process for the Production of Biodiesel. Sep. Sci. Technol.. 1995;30:2021-2033.

- [Google Scholar]

- Optimization and kinetics of biodiesel production from Mahua oil using manganese doped zinc oxide nanocatalyst. Renew. Energy. 2017;103:641-646.

- [Google Scholar]

- Production of biodiesel from castor oil using iron (II) doped zinc oxide nanocatalyst. Renew. Energy. 2016;98:101-107.

- [Google Scholar]

- New heterogeneous process for biodiesel production: A way to improve the quality and the value of the crude glycerin produced by biodiesel plants. Catalysis Today 2005:190-192.

- [Google Scholar]

- Magnetic separation of fatty acids with iron oxide nanoparticles and application to extractive deacidification of vegetable oils. Green Chem.. 2012;14:1786.

- [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, J., Ribeiro, a, Castro, J., Vilarinho, C., Castro, F., 2011. Biodiesel Production By Microalgae and Macroalgae From North Littoral Portuguese Coast 5–10.

- Modern heterogeneous catalysts for biodiesel production: a comprehensive review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev.. 2011;15:4378-4399.

- [Google Scholar]

- Using FTIR spectroscopy for rapid determination of lipid accumulation in response to nitrogen limitation in freshwater microalgae. Bioresour. Technol.. 2010;101:4499-4507.

- [Google Scholar]

- Progress and recent trends in biofuels. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci.; 2007.

- Chickens fed with biomass of the red microalga Porphyridium sp. have reduced blood cholesterol level and modified fatty acid composition in egg yolk. J. Appl. Phycol.. 2000;12:325-330.

- [Google Scholar]

- Total lipid and fatty acid composition of seaweeds for the selection of species for oil-based biofuel and bioproducts. GCB Bioenergy. 2012;4:919-930.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparative study of methods chosen by the Association Française de Normalisation (AFNOR) for evaluating sensitizing potential in the albino guinea-pig. Food Chem. Toxicol.. 1983;21:795-805.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis of transportation fuels from biomass: Chemistry, catalysts, and engineering. Chem. Rev.; 2006.

- Zr-SBA-15 as an efficient acid catalyst for FAME production from crude palm oil. Catal. Today. 2011;167:46-55.

- [Google Scholar]

- Review of Various Reaction Parameters and Other Factors Affecting on Production of Chicken Fat Based Biodiesel. Int. J. Mod. Eng. Res.. 2012;2:407-411.

- [Google Scholar]

- Transesterification of palm oil and crude sea mango (Cerbera odollam) oil: the active role of simplified sulfated zirconia catalyst. Biomass Bioenergy. 2012;40:96-104.

- [Google Scholar]

- Seaweeds as a source of nutritionally beneficial compounds - a review. J. Food Sci. Technol.. 2008;45:1-13.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tropical marine macroalgae as potential sources of nutritionally important PUFAs. Food Chem.. 2010;120:749-757.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biodiesel production by heterogeneous catalysts and supercritical technologies. Bioresour. Technol.. 2010;101:7191-7200.

- [Google Scholar]

- Infrared Spectra of Inorganic and Coordination Compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1963

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Biodiesel production: a review. Bioresour. Technol.; 1999.

- Macroalgae: raw material for biodiesel production. Appl. Energy. 2011;88:3318-3323.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anti-biofilm activity of silver nanoparticles against different microorganisms. Biofouling 2013

- [Google Scholar]

- Microalgae for biodiesel production and other applications: a review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev.; 2010.

- Fatty acid methyl esters synthesis from triglycerides over heterogeneous catalysts in the presence of microwaves. Comptes Rendus Chim.. 2004;7:601-605.

- [Google Scholar]

- Core/shell (ZnO/polyacrylamide) nanocomposite: in-situ emulsion polymerization, corrosion inhibition, anti-microbial and anti-biofilm characteristics. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng.. 2016;63:512-522.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bacillus pumilus of Palk Bay origin inhibits quorum-sensing-mediated virulence factors in Gram-negative bacteria. Res. Microbiol.. 2010;161:293-304.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Rapeseed oil transesterification by heterogeneous catalysis. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc.. 1984;61:1593-1597.

- [Google Scholar]

- Green synthesis of protein stabilized silver nanoparticles using Pseudomonas fluorescens, a marine bacterium, and its biomedical applications when coated on polycaprolactam. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2012

- [Google Scholar]

- FTIR Analysis for Quantification of Fatty Acid Methyl Esters in Biodiesel Produced by Microwave-Assisted Transesterification. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Dev.. 2015;6:964-969.

- [Google Scholar]

- Simultaneous transesterification and esterification for biodiesel production with and without a sulphated zirconia catalyst. Fuel. 2012;97:467-475.

- [Google Scholar]

- The effects of vegetable oil properties on injection and combustion in two different diesel engines. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc.. 1984;61:1610-1619.

- [Google Scholar]

- The influence of Fe doping on the structural, magnetic and optical properties of nanocrystalline ZnO particles. J. Magn. Magn. Mater.; 2012.

- Nanoparticulates for antibiofilm treatment and effect of aging on its antibacterial activity. J. Endod. 2010

- [Google Scholar]

- Evolution towards the utilisation of functionalised carbon nanotubes as a new generation catalyst support in biodiesel production: an overview. RSC Adv.. 2013;3:9070.

- [Google Scholar]

- Commercialization potential of microalgae for biofuels production. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev.. 2010;14:2596-2610.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biodiesel production through the use of different sources and characterization of oils and their esters as the substitute of diesel: a review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev.. 2010;14:200-216.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biodiesel production from Ulva linza, Ulva tubulosa, Ulva fasciata, Ulva rigida, Ulva reticulate by using Mn2ZnO4 heterogenous nanocatalysts. Fuel. 2019;255:115744

- [Google Scholar]

- The application of micro-FTIR spectroscopy to analyze nutrient stress-related changes in biomass composition of phytoplankton algae. Plant Physiol. Biochem.. 2005;43:717-726.

- [Google Scholar]

- Transesterification of soybean oil with zeolite and metal catalysts. Appl. Catal. A Gen.. 2004;257:213-223.

- [Google Scholar]

- A review on novel processes of biodiesel production from waste cooking oil. Appl. Energy. 2013

- [Google Scholar]

- Calcium-based mixed oxide catalysts for methanolysis of Jatropha curcas oil to biodiesel. Biomass Bioenergy. 2011;35:827-834.

- [Google Scholar]

- Beneficial role of sulfated polysaccharides from edible seaweed Fucus vesiculosus in experimental hyperoxaluria. Food Chem.. 2007;100:1552-1559.

- [Google Scholar]

- Inhibitory effects of Bacillus licheniformis (DAB1) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (DAP1) against Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolated from Fenneropenaeus indicus. Int: Aquac; 2013.

- Ferromagnetism in Fe-doped ZnO bulk samples. J. Magn. Magn. Mater.; 2008.

- Microalgae as biodiesel & biomass feedstocks: review & analysis of the biochemistry, energetics & economics. Energy Environ. Sci.. 2010;3:554.

- [Google Scholar]

- Transesterification of soybean oil to biodiesel using zeolite supported CaO as strong base catalysts. Fuel Process. Technol.. 2012;109:13-18.

- [Google Scholar]

- Alumina-supported potassium iodide as a heterogeneous catalyst for biodiesel production from soybean oil. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem.. 2006;255:1-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Esterification and transesterification on Fe2O3-doped sulfated tin oxide catalysts. Catal. Commun.. 2011;12:593-596.

- [Google Scholar]

- Transesterification of canola oil catalyzed by nanopowder calcium oxide. Fuel Process. Technol.. 2013;114:154-162.

- [Google Scholar]