Translate this page into:

Toxicity of different insecticides against the dwarf honey bee, Apis florea Fabricius (Hymenoptera: Apidae)

⁎Corresponding author: Institute of Plant Protection, MNS University of Agriculture, Multan, Pakistan. naeem.iqbal@mnsuam.edu.pk (Naeem Iqbal), khalidtalpur@hotmail.com (Khalid Ali Khan)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Honey bees are considered as critical beneficial insects in the term of honey production and pollination of crops. One of the essential honey bee species in Pakistan is Apis florea Fabricius (Hymenoptera: Apidae). These make nests on trees near human dwellings and agriculture crops. During foraging in the field for nectar and pollen collection from agriculture flowering plants, honey bees may be exposed to pesticide sprays which may cause a change in their foraging behavior and the death of their workers. The current study evaluates the toxicity of six insecticides (emamectin benzoate, spinetoram, chlorantraniliprole, fipronil, flonicamid, and imidacloprid) against workers of A. florea. There were six concentrations of each insecticide (causing > 0% to < 100 % mortality) prepared in water, and each concentration was replicated four times. The experiment was conducted using the diet incorporation method in a plastic container. Emamectin benzoate was found the most toxic insecticide with lower LC50 values (1.02 µg/mL) followed by spinetoram (1.10 µg/mL), chlorantraniliprole (2.74 µg/mL), imidacloprid (3.09 µg/mL), flonicamid (3.94 µg/mL), fipronil (6.00 µg/mL) after 48 h of exposure. The results showed that insecticides are very toxic to A. florea and should be used on agriculture crops with great care and during less activity.

Keywords

Bee keeping

Beneficial insects

Ecotoxicity

Pesticides

Pollinators

1 Introduction

Commercial production in Agriculture usually depends on pesticides such as herbicides, fungicides, insecticides, and other biological controls, including entomopathogenic fungi (Ngowi et al., 2007; Qasim et al., 2018; Qasim et al., 2021). Most of these synthetic pesticides are broad-spectrum and have been extensively used in agriculture since the 1940s (Coats, 2012). This over-reliance on pesticides had not only caused environmental contamination but also negatively affected biodiversity (Desneux et al., 2007; Khan, 2021).

Pollination is the essential ecosystem service that animals mainly provide. Among animals, insect arthropods occupy a significant place because they contribute more to farmlands in terms of pollination (Ahmad et al., 2021; Khan and Ghramh, 2021; Klein et al., 2007). Insect pollination is worth €153 billion a year globally (Gallai et al., 2009). When it comes to pollination, bees, especially honey bees, are the most important, as they account for more than 80% of the process (Hu et al., 2008; Suwannapong et al., 2011). Honey bees are also important because they provide many other valuable products such as bee wax and royal jelly and bee pollen and honey (Ghramh et al., 2020; Ghramh et al., 2019; Khan et al., 2016; Nieh, 1998).

Among honey bees, dwarf honey bee, Apis florea Fabricius (Hymenoptera: Apidae) is an essential pollinator of vegetables, fruits, and other flowering plants (Abrol, 2010) and is mainly found in the Indian subcontinent, Iran, and Oman (Hepburn and Hepburn, 2005). It also has a higher temperature tolerance than other honeybee species (Bhattacharyya et al., 2019), but its population decreases drastically near agriculture farms. According to Sihag (2021), the foraging populations of this species had declined in Raya (Brassica juncea Czern & Coss) and Carrot (Daucus carota L.) from 31.20 ± 3 bees/m2 to 9.20 ± 2 bees/m2 in crops. As a result of the colony and forager surveys, it appeared that A. florea was in danger of extermination, resulting in a pollination crisis (Sihag, 2021). It is believed that insecticides constitute a significant factor in the current decline of A. florae populations (Klein et al., 2007) because honeybees have a slower detoxification system that leads to bees' death (Husain et al., 2014; Jung et al., 2020). Moreover, insecticide residues have also been reported in hive products such as wax, honey, and pollen which may cause bio-magnification of residues at higher trophic levels (Gómez-Ramos et al., 2016).

Many studies report the effects of various pesticides on different species of honey bees, but there are a few studies from Pakistan reporting lethal effects on A. florea. In the current study, we aimed to evaluate the toxicity of six insecticides against A. florea. The insecticides were selected based on their different mode of action. Spinetoram affects postsynaptic acetylcholine receptors and GABA receptors and is a broad-spectrum insecticide (Shimokawatoko et al., 2012). In insects, emamectin benzoate (avermectins) may bind to multiple sites in chloride channels such as glutamate and GABA, resulting in generalized cell dysfunction and nerve impulse disruption (Jansson et al., 1997). Activator of insect ryanodine receptors, chlorantraniliprole causes muscle dysfunction and paralysis (Hannig et al., 2009). The nAChR-binding to neonicotinoids has been studied, while fipronil has been reported as binding to GABA-receptors in the nervous systems (Simon-Delso et al., 2015).

The farmers have extensively used these insecticides on-field and fruit crops. Hence, the purpose of the study was to find out the most toxic and harmful insecticide for A. florea so that the recommendations can be made on their proper and judicious use to conserve A. florea in the area.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Collection of Apis florea

The research was conducted at MNS University of Agriculture, Multan, Punjab, Pakistan. The experts collected three hives of A. florea from the trees located at Multan and Lodhran districts, placed them in the plastic bucket, and shifted them to the laboratory. They were placed in the laboratory for one day for acclimatization before use. During this time, they were fed a 20% sugar-water solution.

2.2 Insecticides

The insecticide used in the study include Emamectin benzoate 1.5%, Spinetoram 12% SC, Chlorantraniliprole 20% SC, Fipronil 5% SC, Flonicamid 50% DF and Imidacloprid 20% SL. These insecticides were purchased from the commercial market.

2.3 Lethal concentration and lethal time estimation

No-choice feeding bioassays were performed to determine the trends in mortality of A. florea by following the methodology of Laurino et al. (2011) with slight modification. Six concentrations (causing > 0% and < 100 % mortality) were prepared by serial dilution in 50% sugar solution for each of the six insecticides. Five healthy foraging workers were introduced into the box (0.5 L). Each concentration was repeated four times. There were four control boxes for each insecticide. The boxes were then placed at 25 ± 2 °C, and 70% ± 5 % R.H. A filter paper underneath the box's cover was wetted with distilled water daily during the treatment. Mortality was recorded after 12, 24, 36, and 48 h of exposure. Workers were considered dead when they showed no movement upon probing with a fine brush. From this data, lethal time was also calculated.

2.4 Data analysis

Abbott’s formula (1925) was used for corrected mortality if the mortality in control was more than 5%. Data were analyzed by probit analysis using SPSS software (Version 23.0 for windows, SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA) to determine median lethal concentrations (LC50) and lethal time (LT50).

3 Results

3.1 Lethal concentration estimation (LC50)

Emamectin benzoate was found more toxic due to low value of LC50 followed by spinetoram, chlorantraniliprole, imidacloprid, flonicamid and fipronil. The LC50 value of emamectin benzoate was 2.01, 1.67, 1.02 and 0.81 µg/mL after 12, 24, and 36 h, respectively. The LC50 of imidacloprid ranged from 6.82 to 1.05 µg/mL during 24–48 h (Table 1). c = Chi-square.

Insecticide

Time (hr)

LC50a

(95%CLb)

d.f

χ2 c

P

nd

Chlorantraniliprole

12

4.95

3.90–9.16

5

0.75

0.98

120

Emamectin benzoate

2.01

0.39–3.55

4

0.62

0.96

120

Fipronil

11.57

6.63–17.08

3

0.83

0.84

120

Flonicamid

12.67

4.56–47.99

5

0.36

0.99

120

Imidacloprid

16.61

11.26–26.23

5

4.11

0.53

120

Spinetoram

4.91

3.64–11.20

4

0.5

0.97

120

Chlorantraniliprole

24

3.3

1.92–4.90

5

0.94

0.96

120

Emamectin benzoate

1.67

0.52–2.76

4

1.41

0.84

120

Fipronil

8.41

4.22–12.58

3

0.09

0.99

120

Flonicamid

6.09

2.27–12.17

5

0.25

0.99

120

Imidacloprid

6.82

3.90–11.01

5

4.68

0.45

120

Spinetoram

4.75

3.54–10.35

4

0.21

0.99

120

Chlorantraniliprole

36

2.74

1.50–4.14

5

1.38

0.92

120

Emamectin benzoate

1.02

0.36–2.05

4

2.97

0.56

120

Fipronil

6

3.77–9.69

3

0.81

0.84

120

Flonicamid

3.94

1.84–6.57

5

1.28

0.93

120

Imidacloprid

3.09

1.81–4.56

5

0.58

0.9

120

Spinetoram

1.1

0.19–2.21

4

0.26

0.99

120

Chlorantraniliprole

48

1.47

0.53–2.51

5

0.77

0.98

120

Emamectin benzoate

0.81

0.14–1.53

4

1.13

0.89

120

Fipronil

3.52

0.99–6.14

3

0.24

0.97

120

Flonicamid

1.34

0.34–2.58

5

1.36

0.92

120

Imidacloprid

1.05

0.28–1.91

5

1.38

0.92

120

Spinetoram

0.97

0.26–1.62

4

0.44

0.97

120

3.2 Percentage mortality

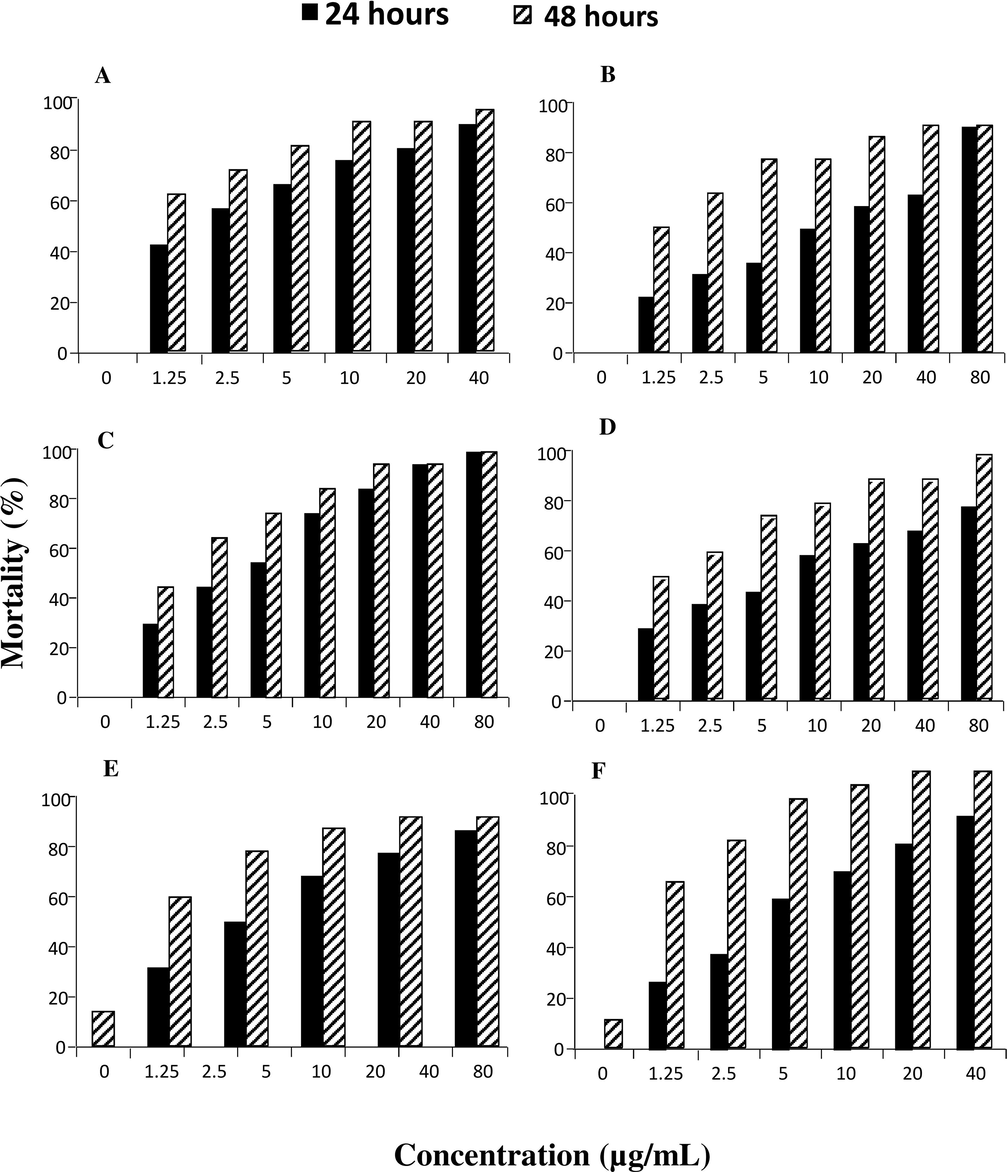

Percent mortality of the A. florea population exposed to emamectin benzoate is shown in Fig. 1A. Mortality was ranged between 45.00 and 95.00% after 24 h of exposure. While, mortality range observed after 48 h of exposure was 65.00–100.00%. After 24 h of exposure, lower mortality i.e. 45.00% was observed in case of the lowest concentration viz. 1.25 µg/mL. It increased to the highest i.e. 95.00% after 24 h of exposure to emamectin benzoate. Similarly, after 48 h of exposure the mortality was low i.e. 65.00% which gradually increased to maximum (100.00%) in the highest concentration viz. 40 µg/mL. Fig. 1B shows the percent mortality of A. florea subjected to imidacloprid. After 24 h of exposure, the mortality rate ranged from 25.00 to 95.00%. After 48 h of exposure, percent mortality varied from 55.00 to 100.00%. The lowest concentration of 1.25 µg/mL resulted in 25.00 percent mortality after 24 h of exposure. After 24 h of exposure to the highest dose of imidacloprid (80 µg/mL), it reached to the maximum of 100.00%. Mortality was reduced to 55.00% after 48 h of exposure, but reached a maximum (100.00%) at the highest concentration of 80 µg/mL. In Fig. 1C, the chlorantraniliprole-induced mortality rate of A. florea is depicted. The mortality varied from 30.00 to 95.00% after 24 h of exposure. Similarly, mortality rates ranged from 45 to 100% after 48 h of exposure. Even at the lowest dosage of 1.25 µg/mL, the mortality rate after 24 h was 30.00%. Chlorantraniliprole (80 µg/mL) exposure for 24 h resulted in a maximum of 100.00%. Mortality was 45.00% at the lowest concentration after 48 h of exposure and 100.00% at the highest concentration of 80 µg/mL.

Mortality (%) of A. florea after 24 and 48 hours of exposure to emamectin benzoate (A), imidacloprid (B), chlorantraniliprole (C), flonicamid (D), fipronil (E) and spinetoram (F).

Percent mortality of the A. florea populations have been shown in Fig. 1D, after exposure to flonicamid. After 24 h of exposure, mortality rate ranged between 30.00 and 77.00%. While, mortality range was ranged between 50.00% and 100.00% after 48 h of treatment. After 24 h, the lowest percent mortality (30.00%) was found at the lowest concentration viz. 1.25 µg/mL. The highest i.e. 77.00% mortality rate was observed after 24 h of exposure to flonicamid. Similarly after 48 h, percent mortality was the lowest (50.00%) which reached to the highest (100.00%) at the maximum concentration viz. 80 µg/mL. Fig. 1E is showed the percent mortality of A. florea subjected to fipronil. After 24 h of exposure, the percent mortality ranged from 35.00 to 95.00%. After 48 h of exposure, percent mortality varied from 65.00 to 100.00%. The lowest concentration of 5.00 µg/mL resulted in 35.00% mortality after 24 h of exposure. After 24 h of exposure to the highest concentration of fipronil (40 µg/mL), it reached a maximum of 100.00%. Mortality was 65.00% at the lowest concentration after 48 h of exposure, but reached to maximum (100.00%) at the highest concentration of 40 µg/mL. In Fig. 1F, the spinetoram-induced mortality rate of A. florea is depicted. The mortality varied from 0.00 to 85.00% after 24 h of exposure. Similarly, mortality rates ranged from 10 to 100% after 48 h of exposure. Even at the lowest dosage of 1.25 µg/mL, the mortality rate after 24 h was 25.00%. The highest concentration of spinetoram (40 µg/mL) showed 85.00% mortality rate after 24 h. The mortality was 60.00% at the lowest concentration after 48 h of exposure and 100.00% at the highest concentration of 40 µg/mL.

3.3 Lethal time estimation (LT50)

A decrease in LT50 values was observed as the concentration of insecticide increased. The minimum recorded LT50 values for Emamectin benzoate was 5.09 h at 10 µg/ml and 5.63 h at 40 µg/mL and followed by spinetoram with LT50 values of 8.99 h at 10 µg/mL and 6.46 h at 20 µg/mL. The LT50 value of spinetoram was 5.22 h at 40 µg/ml, and no LT50 value was calculated at 80 µg/mL because all individuals died. For Chlorantraniliprole, the LT50 values were 14.11 h at 10 µg/mL and 5.16 h at 80 µg/mL. The LT50 values for other insecticides are given in Table 2. c = Chi-square. d = Numbers of workers exposed.

Insecticide

Concentration (µg/mL)

LT50a

(95%CLb)

d.f

χ2 c

P

Chlorantraniliprole

10

14.11

0.00–23.20

2

0.54

0.76

Emamectin benzoate

5.09

0.00–12.41

2

0.29

0.86

Fipronil

15.89

4.74–22.89

2

0.86

0.65

Flonicamid

14.97

1.96–22.68

2

0.13

0.93

Imidacloprid

18.71

10.52–25.02

2

0.31

0.86

Spinetoram

8.99

0.15–15.45

2

2.58

0.28

Chlorantraniliprole

20

8.17

0.01–17.02

2

1.81

0.4

Emamectin benzoate

5.87

0.00–12.74

2

0.61

0.74

Fipronil

8.05

0.07–14.38

2

0.79

0.67

Flonicamid

11.46

0.97–18.06

2

0.75

0.68

Imidacloprid

13.29

6.16–18.09

2

1.52

0.46

Spinetoram

6.46

0.00–12.48

2

3.23

0.19

Chlorantraniliprole

40

5.87

1.62–12.74

2

0.61

0.73

Emamectin benzoate

5.63

1.27–10.83

2

0.54

0.76

Fipronil

6.76

0.17–11.85

2

1.15

0.56

Flonicamid

9.07

0.01–16.23

2

0.49

0.78

Imidacloprid

11.29

4.58–15.53

2

3.58

0.17

Spinetoram

5.22

0.00–10.88

2

1.49

0.48

Chlorantraniliprole

80

5.16

0.00–11.50

2

0.68

0.71

Emamectin benzoate

–

–

–

–

–

Fipronil

5.19

0.00–10.38

2

0.77

0.68

Flonicamid

9.52

2.65–13.91

2

1.49

0.47

Imidacloprid

–

–

–

–

–

Spinetoram

–

–

–

–

–

4 Discussion

Different insecticides pose varying risks to dwarf honey bees, as shown in the present study. The present study also identifies which insecticide has the most negligible impact on honey. Our research shows that the toxic effects of Emamectin benzoate are more significant on beneficial arthropods, especially on pollinators and honeybees, and are well-documented in the literature (Ioriatti et al., 2009). The emamectin benzoate LC50 was 2.01, 1.67, and 1.02 g/mL after 12 h, 24 h, and 48 h. These findings are comparable to the findings of Cang (2007), who have reported that emamectin benzoate was the most toxic against bees among different insecticides. Emamectin benzoate is more toxic because of its lower detoxification during metabolism, and it can penetrate more. The absorption coefficient of avermectins is high, and due to this reason, avermectin is considered highly toxic to bees (Abdu-Allah, 2011; Lumaret et al., 2012). However, field trials conducted on emamectin benzoate have depicted a low half-life in the sunlight. So, it can be added to the IPM program depending on the location (Lumaret et al., 2012). The LC50 values for fipronil were 8.41, 6.00, and 3.52 µg/mL after 24, 48, and 72 h respectively. The value is higher compared to other LC50 values of other insecticides. It is less toxic because of higher LC50 results; following the findings of Castro-Janer (2010), fipronil effectiveness against many organisms has decreased due to its overuse in the field. Many arthropods like houseflies, diamondback moths, cockroaches, etc., have developed resistance (Kristensen et al., 2004; Li et al., 2006; Khan, 2021). However, it has been proven that fipronil degradation varies with plant species. A single enantiomer of fipronil is unlikely to decrease the harm fipronil causes to honeybees. If researchers reduce the use of fipronil, they should improve the application methods based on the safest time and bloom circumstances (Li et al., 2009).

Emamectin benzoate depicted lower LT50 value than any other insecticides used in the study. At 10, 20, and 40 µg/mL, the LT50 values of emamectin benzoate were 5.09, 5.87, and 5.63 h, respectively. The LT50 could not be ascertained for 80 µg/mL because all 20 exposed individuals died. According to Jansson (1997), emamectin benzoate has shown different results under different conditions. Different conditions, such as in the labaoratory and field, produced different results during his experiment. For example, emamectin benzoate is less toxic during field trials than in laboratory experiments. When applied topically, emamectin benzoate killed insects at a rate of 100 percent (Reynolds, 2017). Imidacloprid had a long half-life (LT50) when compared to other insecticides. LT50 values were found for imidacloprid at 10, 20, and 40 ug/mL: 18.70, 13.28, and 11.21 h. Honey bees' acute response to imidacloprid has been documented in the past (Suchail, 2000). As Roy et al. (2016) found, the LT50 value in our study was about 10 h and 100 ug/mL, and the fiducial limit was around 9.30–12.20. A low concentration of 40 µg/mL provided the LT50 value of 11.22 h. These values showed that honey bees are susceptible to insecticidal exposures. In the present study, fipronil and chlorantraniliprole were the least toxic insecticides, while emamectin benzoate was the most toxic insecticide against A. florea. The low toxicity of chlorantraniliprole can be attributed to the fact that it is unlikely to reach and affect the target sites, ryanodine receptors, in honey bees when dissolved in watery solutions (Dinter et al. 2010). Hence, care should be taken while using pesticides in agriculture area by taking into account the foraging time of bees.

5 Conclusion

The A. florea is one of the essential pollinators in Southeast Asia and the most common dwarf honeybee. Its importance is due to its services like pollination and honey production. But insecticides are toxic to A. florea, which in turn significantly reducing their numbers. Insecticides residues in pollen grains result in physiological changes, behavioral changes, and also mortality; as a result, decreased colony performance is observed. Honeybees have minor adaptation and are essential as well, so care should be taken during pesticide application. And steps should be taken to conserve this vital creature.

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to MNS University of Agriculture, Multan, for their support during this research work. The authors also appreciate the support of the Research Center for Advanced Materials Science (RCAMS) at King Khalid University Abha, Saudi Arabia, through project number KKU/RCAMS/G-002-21

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Potency and residual activity of emamectin benzoate and spinetoram on Spodoptera littoralis (Boisd.) African Entomol.. 2011;19:733-737.

- [Google Scholar]

- Foraging behaviour of Apis florea F., an important pollinator of Allium cepa L. J. Apic. Res.. 2010;49(4):318-325.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of native pollinator communities on the physiological and chemical parameters of loquat tree (Eriobotrya japonica) under open field condition. Saudi J. Biol. Sci.. 2021;28(6):3235-3241.

- [Google Scholar]

- Proboscis extension reflex in Apis florea (Hymenoptera: Apidae) in response to temperature. J. Entomol. Sci.. 2019;54(3):238-249.

- [Google Scholar]

- Toxicity and Safety Evaluation of Emamectin benzoate on Four Types of Non-target Organism. Pesticides-Shenyang-. 2007;46(7):481.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnoses of fipronil resistance in Brazilian cattle ticks (Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) microplus) using in vitro larval bioassays. Vet. Parasitol.. 2010;173(3-4):300-306.

- [Google Scholar]

- Insecticide Mode of Action. Academic Press; 2012.

- The sublethal effects of pesticides on beneficial arthropods. Annu. Rev. Entomol.. 2007;52(1):81-106.

- [Google Scholar]

- Economic valuation of the vulnerability of world agriculture confronted with pollinator decline. Ecol. Econ.. 2009;68(3):810-821.

- [Google Scholar]

- Quality evaluation of Saudi honey harvested from the Asir province by using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) Saudi J. Biol. Sci.. 2020;27(8):2097-2105.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antibacterial potential of some Saudi honeys from Asir region against selected pathogenic bacteria. Saudi J. Biol. Sci.. 2019;26(6):1278-1284.

- [Google Scholar]

- Screening of environmental contaminants in honey bee wax comb using gas chromatography–high-resolution time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res.. 2016;23(5):4609-4620.

- [Google Scholar]

- Feeding cessation effects of chlorantraniliprole, a new anthranilic diamide insecticide, in comparison with several insecticides in distinct chemical classes and mode-of-action groups. Pest Manag. Sci. formerly Pestic Sci.. 2009;65(9):969-974.

- [Google Scholar]

- Early steps of angiosperm–pollinator coevolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.. 2008;105(1):240-245.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bioassay of insecticides against three honey bee species in laboratory conditions. Cercetări Agronomice în Moldova.. 2014;47(2) 158:69-79.

- [Google Scholar]

- Toxicity of emamectin benzoate to Cydia pomonella (L.) and Cydia molesta (Busck) (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae): laboratory and field tests. Pest Manag. Sci. formerly. Pestic. Sci.. 2009;65(3):306-312.

- [Google Scholar]

- Jansson, R.K., Brown, R., Cartwright, B., Cox, D., Dunbar, D.M., Dybas, R.A., Eckel, C., Lasota, J.A., Mookerjee, P.K., Norton, J.A., 1996 Emamectin benzoate : A novel avermectin derivative for control of lepidopterous pests. In The Management of Diamondback Moth and Other Crucifer Pests: Proceedings of the Third International Workshop, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 29 October–1 November, Sivapragasam, A., Loke, W.H., Hussan, A.K., Lim, G.S., Eds.; Malaysian Agricultural Research and Development Institute, Malaysian Plant Protection Society: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 1997; pp. 171–177.

- October. Emamectin benzoate: a novel avermectin derivative for control of lepidopterous pests. In: In Proceedings of the 3rd International Workshop on Management of Diamondback Moth and Other Crucifer Pests. MARDI, Kuala Lumpur. 1997. p. :1-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Jansson, R.K., Brown, R., Cartwright, B., Cox, D., Dunbar, D.M., Dybas, R.A., Eckel, C., Lasota, J.A., Mookerjee, P.K., Norton, J.A. and Peterson, R.F., 1997, October. Emamectin benzoate: a novel avermectin derivative for control of lepidopterous pests. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Workshop on Management of Diamondback Moth and Other Crucifer Pests. MARDI, Kuala

- Safety of Dwarf Honeybee, Apis florea in Relation with Agricultural Pest Management. In: The Future Role of Dwarf Honeybees in Natural and Agricultural Systems. CRC Press; 2020. p. :125-136.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pyriproxyfen induces lethal and sublethal effects on biological traits and demographic growth parameters in Musca domestica. Ecotoxicology. 2021;30:610-621.

- [Google Scholar]

- Permethrin resistance associated with inherited genes in a near-isogenic line of Musca domestica. Pest Management Science. 2021;77:963-969.

- [Google Scholar]

- The characterization of blossom honeys from two provinces of Pakistan. Italian J. Food Sci.. 2016;28:625-638.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pollen source preferences and pollination efficacy of honey bee, Apis mellifera (Apidae: Hymenoptera) on Brassica napus crop. J. King Saud Univ. Sci.. 2021;33(6):101487.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Importance of pollinators in changing landscapes for world crops. Proc. R. Soc.. 2007;274(1608):303-313.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cross-resistance potential of fipronil in Musca domestica. Pest Manag. Sci.. 2004;60(9):894-900.

- [Google Scholar]

- Toxicity of neonicotinoid insecticides to honey bees: laboratory tests. Bull. Insectol.. 2011;64(1):107-113.

- [Google Scholar]

- A Review on the Toxicity and Non-Target Effects of Macrocyclic Lactones in Terrestrial and Aquatic. Environ.. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol.. 2012;13:1004-1060.

- [Google Scholar]

- Smallholder Vegetable Farmers in Northern Tanzania: Pesticides Use Practices, Perceptions. Cost Health Effects. Crop Protec.. 2007;26(11):1617-1624.

- [Google Scholar]

- The role of scent beacon in the communication of food location by the stingless bee, Melipona panamica. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol.. 1998;43:47-58.

- [Google Scholar]

- Temperature-dependent development of Asian citrus psyllid on various hosts, and mortality by two strains of Isaria. Microb. Pathog.. 2018;119:109-118.

- [Google Scholar]

- Host-pathogen interaction between Asian citrus psyllid and entomopathogenic fungus (Cordyceps fumosorosea) is regulated by modulations in gene expression, enzymatic activity and HLB-bacterial population of the host. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C: Toxicol. Pharmacol.. 2021;248:109112

- [Google Scholar]

- Efficacy of chemicals for the potential management of the Queensland fruit fly Bactrocera tryoni (Froggatt) (Diptera: Tephritidae) Insects. 2017;8(2):49.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparative bioefficacy of some systemic insecticides against Lipaphis erysimi K. infesting mustard vis-à-vis laboratory evaluation for their toxicity on Apis mellifera L. The Bioscan.. 2016;11:741-746.

- [Google Scholar]

- Development of the novel insecticide spinetoram (Diana®). Ltd, Tokyo: Sumitomo Chemical Co.; 2012.

- The red dwarf honey bee (Apis florea F.) faces the threat of extirpation in Northwest India. Ukr. J. Ecol.. 2021;11(2):1-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- Systemic insecticides (neonicotinoids and fipronil): trends, uses, mode of action and metabolites. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res.. 2015;22(1):5-34.

- [Google Scholar]

- Characteristics of imidacloprid toxicity in two Apis mellifera subspecies. Environ. Toxicol. Chem.. 2000;19:1901-1905.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nosema ceranae, a new parasite in Thai honeybees. J. Invertebr. Pathol.. 2011;106(2):236-241.

- [Google Scholar]