Translate this page into:

Structure-based virtual screening of phytochemicals and repurposing of FDA approved antiviral drugs unravels lead molecules as potential inhibitors of coronavirus 3C-like protease enzyme

⁎Corresponding authors. arunbgurung@gmail.com (Arun Bahadur Gurung), joongku@cnu.ac.kr (Joongku Lee)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Coronaviruses are enveloped positive-strand RNA viruses belonging to family Coronaviridae and order Nidovirales which cause infections in birds and mammals. Among the human coronaviruses, highly pathogenic ones are Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) and the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) which have been implicated in severe respiratory syndrome in humans. There are no approved antiviral drugs or vaccines for the treatment of human CoV infection to date. The recent outbreak of new coronavirus pandemic, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has caused a high mortality rate and infections around the world which necessitates the need for the discovery of novel anti-coronaviral drugs. Among the coronaviruses proteins, 3C-like protease (3CLpro) is an important drug target against coronaviral infection as the auto-cleavage process catalysed by the enzyme is crucial for viral maturation and replication. The present work is aimed at the identification of suitable lead molecules for the inhibition of 3CLpro enzyme via a computational screening of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved antiviral drugs and phytochemicals. Based on binding energies and molecular interaction studies, we shortlisted five lead molecules (both FDA approved drugs and phytochemicals) for each enzyme targets (SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro, SARS-CoV 3CLpro and MERS-CoV 3CLpro). The lead molecules showed higher binding affinity compared to the standard inhibitors and exhibited favourable hydrophobic interactions and a good number of hydrogen bonds with their respective targets. A few promising leads with dual inhibition potential were identified among FDA approved antiviral drugs which include DB13879 (Glecaprevir), DB09102 (Daclatasvir), molecule DB09297 (Paritaprevir) and DB01072 (Atazanavir). Among the phytochemicals, 11,646,359 (Vincapusine), 120,716 (Alloyohimbine) and 10,308,017 (Gummadiol) showed triple inhibition potential against all the three targets and 102,004,710 (18-Hydroxy-3-epi-alpha-yohimbine) exhibited dual inhibition potential. Hence, the proposed lead molecules from our findings can be further investigated through in vitro and in vivo studies to develop into potential drug candidates against human coronaviral infections.

Keywords

Coronaviruses

3C-like protease

SARS-CoV

MERS-CoV

Molecular docking

Virtual screening

FDA approved drugs

Antiviral drugs

Phytochemicals

1 Introduction

Coronaviruses belong to the Coronavirinae subfamily, family Coronaviridae and order Nidovirales. The subfamily members based on genomic structure and phylogenetic study can be classified under four genera — Alpha-, Beta-, Gamma- and Delta-coronavirus (Cui et al., 2019). The first two genera cause infections in only mammals while birds and mammals are commonly infected by Gamma- and Delta-coronaviruses (Woo et al., 2012). While Alpha-coronaviruses and Beta-coronaviruses are known to cause gastroenteritis in animals, in humans, they commonly cause respiratory distress (Cui et al., 2019). There are four human coronaviruses such as HCoV-229E, HKU1, HCoV-NL63 and HCoV-OC43 which induce mild upper respiratory infections and two highly pathogenic ones, such as Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) implicated in severe respiratory syndrome in humans (Forni et al., 2017; Su et al., 2016). All human coronaviruses are reported to have animal origins based on the current sequence studies, for example, SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, HCoV-229E and HCoV-NL63 have been originated in bats while HKU1 and HCoV-OC43 are probably linked to rodents (Forni et al., 2017; Su et al., 2016). The intermediate hosts such as domestic animals may play a significant role in facilitating the easy transfer of viruses from natural hosts to humans (Cui et al., 2019). Furthermore, domestic animals themselves are susceptible to bat-borne or closely related coronavirus diseases (Lacroix et al., 2017; Simas et al., 2015). At present, 7 of 11 species of Alpha-coronavirus specified by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) and 4 of 9 species of Beta-coronavirus have been reported only in bats. Consequently, bats are probably the main natural reservoirs of Alpha- and Beta-coronaviruses (Woo et al., 2012).

Coronaviruses are enveloped viruses of about 80–120 nm in diameter, with round and often pleiomorphic virions. They contain positive-strand RNA, with the largest genome (∼30 kb) known till date (Lai, 2001). A helical capsid found within the viral membrane is composed of genomic RNA complexed with the basic nucleocapsid (N) protein. All coronaviruses display at least three membrane viral proteins. This includes type I glycoprotein, spike (S) protein which forms peplomers on the surface and gives a characteristic crown-like appearance, the membrane (M) protein and a small membrane protein, an envelope protein (E). All coronaviruses have a similar genomic structure (Weiss and Navas-Martin, 2005). The replicase gene located within 5′ region approximately 20–22 kb encodes several enzymatic activities. The gene products of the replicase are encoded within two very large open reading frames, ORFs 1a and 1b, which are translated by a frameshift mechanism into two large polypeptides, pp1a and pp1ab (Gorbalenya, 2001; Lee et al., 1991). With the help of S protein, coronaviruses bind to their specific host cellular receptors. On gaining entry into the cell, pp1a and pp1ab are translated from the viral genome RNA, ORFs 1a and 1b (Bredenbeek et al., 1990; Brian and Baric, 2005). The ORF1a encodes a picornavirus 3C-like protease (3CLpro) and one or two papain-like proteases (PLpro or PLP). These proteases catalyze the processing of viral pp1a and pp1ab into the mature replicase proteins (Lee et al., 1991; Ziebuhr et al., 2001). The enzymes such as RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp), a helicase (1 1 6) and others are encoded in ORF 1b and processed from pp1ab (Gorbalenya, 2001). The metabolism of coronavirus RNA and disruption of host cell processes are believed as a result of the catalytic activities of various enzymes (Ziebuhr, 2005).

As aforementioned, SARS- and MERS-CoVs genome harbours two ORFs: ORF1a and ORF1b wherein ORF1a encodes two cysteine proteases viz; a papain-like protease (PLpro) and a 3C-like protease (3CLpro) also known as main protease (Mpro). While PLpro manages cleavage on the first three cutting sites of its polyprotein, 3CLpro is responsible for cleavage at other eleven positions causing the release of sixteen non-structural proteins (nsp) (Jo et al., 2020). The crystal structures of SARS- and MERS-CoVs 3CLpro reveal the presence of three structural domains in each monomer wherein domains I and II has a characteristic chymotrypsin-like fold with a catalytic cysteine and are linked to a third C-terminal domain by a long loop (Needle et al., 2015). Therefore, 3CLpro is an important drug target against coronaviral infection as the auto-cleavage process is indispensable for viral maturation and replication (Jo et al., 2020).

The recent outbreak of new coronavirus pandemic or coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has caused high mortality rate and infections around the world (Wu et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2020) warrants the need for the discovery of new effective antiviral therapeutics against coronaviral infections. There are no approved antiviral drugs or vaccines for the treatment of human CoV infection to date, though many candidate therapeutics have been investigated in pre-clinical studies (Abd El-Aziz and Stockand, 2020; Dhama et al., 2020; Graham et al., 2013; Lundstrom, 2020; Padron-Regalado, 2020). Although many attempts have been previously made by workers to identify specific inhibitors for 3CLpro enzymes, a few studies have been done to target all the three coronavirus protease enzymes (SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro, SARS-CoV 3CLpro and MERS-CoV 3CLpro) using small molecules. In this study we aimed at finding suitable lead molecules for the inhibition of 3CLpro enzymes through virtual screening of two chemical datasets viz; Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved antiviral drugs and selected phytochemicals. We have proposed five lead molecules as potential inhibitors for each enzyme targets. These lead molecules could be further investigated for developing as drugs against anti-coronaviral infection.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Selection and retrieval of phytochemicals and FDA approved drugs

A total of 263 phytochemicals and 75 FDA approved antiviral drugs were retrieved from the database of Indian Plants, Phytochemistry And Therapeutics (IMPPAT) (Mohanraj et al., 2018) and DrugBank database (Wishart et al., 2008) respectively. The three-dimensional structure of the molecules was downloaded in SDF format and the molecules whose only two-dimensional structures were available, were converted into the three-dimensional form using OpenBabel software version 2.4.1 (O’Boyle et al., 2011) and optimized using the Merck molecular force field (MMFF94) (Halgren, 1996).

2.2 Screening of drug-like compounds:

The drug-like compounds from the phytochemicals set were filtered based on Lipinski’s rule of five (Lipinski, 2004), Veber’s rule (Veber et al., 2002) and Adsorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion and Toxicity (ADMET) physicochemical parameters. The physicochemical properties of the compounds were evaluated using DataWarrior program version 5.0 (Sander et al., 2015).

2.3 Protein-preparation

The high resolution three dimensional X-ray crystal structures of the enzyme target: SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro, SARS-CoV 3CLpro and MERS-CoV 3CLpro were retrieved from protein data bank (PDB) (http://www.rcsb.org/) using their accession IDs 6Y2F, 3TNT and 5WKK at a resolution of 1.95 Å, 1.59 Å and 1.55 Å respectively. The heteroatoms including ions, cocrystal ligands (O6K, G85 and AW4 corresponding to PDB IDs: 6Y2F, 3TNT and 5WKK respectively) and water molecules were removed. Hydrogen atoms and Kolmann charges were added to the protein using AutoDockTools 1.5.6 (Morris et al., 2009) and the proteins were converted into PDBQT format.

2.4 Ligand preparation

The selected compounds were prepared for docking using AutoDockTools 1.5.6 (Morris et al., 2009). Hydrogen atoms and Gasteiger charges were added to the selected compounds and the torsions were defined for each compound. The structures were saved in PDBQT format.

2.5 Molecular docking study

The binding affinity of each selected compound along with the control with the three enzyme targets was determined using molecular docking approach. The binding sites for the docking were defined by placing a grid box of suitable dimensions centred at each cocrystallized ligand (Table 1). Autodock Vina was used for carrying out molecular docking, which performs docking calculations based on sophisticated gradient optimization method (Trott and Olson, 2010). The binding poses were clustered and ranked in the order of their binding affinities. The molecular interactions (hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions between the target proteins and compounds were studied using LigPlot + version 1.4.5 (Laskowski and Swindells, 2011).

Enzyme targets

AutoDock Vina Search Space

Center

Dimensions (Å)

Exhaustiveness

SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro

x: 10.9372, y: −2.0146, z: 18.2692

25 × 25 × 25

8

SARS-CoV 3CLpro

x: 25.1486, y: 44.1145, z: −5.6121

25 × 25 × 25

8

MERS-CoV 3CLpro

x: −21.9860, y: 25.6036, z: 4.0045

25 × 25 × 25

8

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Virtual screening of drug-like compounds:

A set of 75 FDA approved antiviral drugs and 263 phytochemicals belonging to different classes such as prenol lipids, flavonoids, indoles and derivatives, alkaloids, lignans, organooxygen compounds etc. were used for the present study. Since the FDA approved drugs have already undergone the preclinical and clinical trials and tested safe in patients, the drugs were not tested again using in silico drug-like filters. While plant-derived compounds are much safer to use with fewer adverse effects, we subjected them into virtual screening protocol to reduce the drug-attrition rate. We used the rule of five (ROF) and Veber’s rule filters to test the oral bioavailability of the compounds. According to ROF, a compound is considered to be orally bioactive if their physicochemical properties lie within the safe limits (molecular weight ≤ 500 Da, hydrogen bond donors ≤ 5, hydrogen bond acceptors ≤ 10, and an octanol–water partition coefficient log P ≤ 5) (Lipinski, 2004). Veber's rule states that a good oral bioavailable compound possesses number of rotatable bonds ≤ 10 and topological polar surface area ≤ 140 Å2 (Veber et al., 2002). Further, the molecules were also tested for in silico toxicity studies. Out of 263 phytochemicals, 46 molecules were found to be orally bioactive, non-tumorigenic, non-mutagenic, non-irritant and without any side effects on reproductive health. Thus, these 46 phytochemicals and 75 FDA approved drugs were tested further for their inhibitory potential against the three enzyme targets (Tables 2 and 3).

Drugs

DrugBank ID

Therapy

Ombitasvir

DB09296

Chronic Hepatitis C

Elbasvir

DB11574

Chronic Hepatitis C

Sofosbuvir

DB08934

Chronic Hepatitis C

Ledipasvir

DB09027

Chronic Hepatitis C

Famciclovir

DB00426

Herpes virus infections

Simeprevir

DB06290

Chronic hepatitis C virus

Lopinavir

DB01601

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection.

Tecovirimat

DB12020

Smallpox

Oseltamivir

DB00198

Influenza viruses A and B infections

Baloxavir marboxil

DB13997

Influenza A and influenza B infections

Didanosine

DB00900

HIV infection

Bictegravir

DB11799

HIV-1 and HIV-2 infection

Adefovir dipivoxil

DB00718

Hepatitis B

Zalcitabine

DB00943

HIV infection

Emtricitabine

DB00879

HIV-1 infection

Zidovudine

DB00495

HIV infection

Darunavir

DB01264

HIV-1 infection

Nevirapine

DB00238

HIV-1 infection and AIDS.

Valganciclovir

DB01610

Cytomegalovirus infections

Nelfinavir

DB00220

HIV infection

Foscarnet

DB00529

cytomegalovirus retinitis, HIV infection

Boceprevir

DB08873

Chronic Hepatitis C

Inosine pranobex

DB13156

Viral infection

Dolutegravir

DB08930

HIV-1 infection

Abacavir

DB01048

HIV infection and AIDS.

Edoxudine

DB13421

Herpes simplex virus type 1 and 2 infection

Ribavirin

DB00811

Hepatitis C and viral hemorrhagic fevers

Elvitegravir

DB09101

HIV-1 infection

Amantadine

DB00915

Influenza A infection

Vidarabine

DB00194

Herpes viruses, the vaccinia virus and varicella zoster virus infection

Daclatasvir

DB09102

Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) infection

Tenofovir alafenamide

DB09299

Chronic hepatitis B and HIV-1 infection

Ritonavir

DB00503

HIV infection

Trifluridine

DB00432

Keratoconjunctivitis and recurrent epithelial keratitis

Zanamivir

DB00558

Influenza A and B virus infection

Acyclovir

DB00787

Herpes simplex, Varicella zoster, herpes zoster infection

Ganciclovir

DB01004

AIDS-associated cytomegalovirus infections.

Entecavir

DB00442

Hepatitis B infection

Raltegravir

DB06817

HIV infection

Doravirine

DB12301

HIV-1 Infection

Pibrentasvir

DB13878

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection

Fosamprenavir

DB01319

HIV infection

Glecaprevir

DB13879

HCV infection

Tipranavir

DB00932

HIV infection

Etravirine

DB06414

HIV-1 infection

Amprenavir

DB00701

HIV infection.

Letermovir

DB12070

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection

Favipiravir

DB12466

Influenza

Idoxuridine

DB00249

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection

Rimantadine

DB00478

Influenza.

Tromantadine

DB13288

Herpes zoster and simplex virus infection

Telaprevir

DB05521

Chronic Hepatitis C

Dasabuvir

DB09183

Chronic Hepatitis C

Grazoprevir

DB11575

Chronic Hepatitis C

Docosanol

DB00632

HSV infection

Penciclovir

DB00299

HSV infections

Velpatasvir

DB11613

chronic Hepatitis C

Tenofovir disoproxil

DB00300

HIV infection and Hepatitis B

Cidofovir

DB00369

CMV retinitis

Voxilaprevir

DB12026

Chronic Hepatitis C

Asunaprevir

DB11586

HCV infection

Valaciclovir

DB00577

Hepatitis, HIV, and cytomegalovirus infection

Efavirenz

DB00625

HIV-1 infection

Peramivir

DB06614

Influenza A/B.

Brivudine

DB03312

Herpes zoster.

Telbivudine

DB01265

Hepatitis B virus infection

Maraviroc

DB04835

HIV infection

Stavudine

DB00649

HIV infection

Paritaprevir

DB09297

Chronic Hepatitis C

Indinavir

DB00224

HIV infection

Lamivudine

DB00709

HIV-1 and hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection

Atazanavir

DB01072

HIV infection

Rilpivirine

DB08864

HIV-1 infection

Delavirdine

DB00705

HIV-1.infection

Saquinavir

DB01232

HIV-1 and HIV-2 infection

Molecule Name

CASID/CHEMSPIDER/CID

Class

MW

cLogP

cLogS

HBA

HBD

TPSA

RB

Druglikeness

Heterophylloidine

78174–97-7

Prenol lipids

383.486

2.2205

−3.41

5

0

63.68

2

2.7882

Arjunolone

82178–34-5

Flavonoids

284.266

2.6114

−3.17

5

2

75.99

2

0.40331

Rosicine

95690–65-6

Indoles and derivatives

324.379

0.8137

−3.091

5

1

54.1

2

2.2389

Asparagamine A

156798–15-1

Organooxygen compounds

385.458

2.1085

−3.634

6

0

57.23

3

0.7051

Piscrocin B

752225–57-3

Heteroaromatic compounds

198.173

−0.1119

−1.262

5

3

90.9

2

0.20569

6-Acetylheteratisine

10,246,449

Quinolidines

433.543

1.1579

−3.186

7

1

85.3

4

4.6497

Gummadiol

10,308,017

Furanoid lignans

386.355

2.0507

−3.752

8

2

95.84

2

0.1606

Vidolicine

28,288,759

Indoles and derivatives

352.433

1.5661

−3.47

5

1

54.1

3

2.5754

19-Hydroxy-11-methoxytabersonine

57,619,488

Plumeran-type alkaloids

382.458

1.3822

−3.246

6

2

71.03

4

0.90699

Boldine

10,154

Aporphines

327.379

2.7882

−3.129

5

2

62.16

2

4.6712

Indoline

10,328

Indoles and derivatives

119.166

1.3351

−2.025

1

1

12.03

0

0.19917

Tubotaiwine

100,004

Strychnos alkaloids

324.423

2.3452

−3.568

4

1

41.57

3

1.5804

Cinchonidine

101,744

Cinchona alkaloids

294.397

2.6804

−3.079

3

1

36.36

3

0.88095

Tryptoline

107,838

Indoles and derivatives

172.23

1.2188

−2.39

2

2

27.82

0

1.1795

Alloyohimbine

120,716

Yohimbine alkaloids

354.448

2.3512

−3.065

5

2

65.56

2

1.5035

Cuscohygrine

1,201,543

Alkaloids and derivatives

224.347

1.2932

−1.22

3

0

23.55

4

4.2839

Sebiferine

10,405,046

Phenanthrenes and derivatives

341.406

1.9462

−2.753

5

0

48

3

5.7459

Condylocarpine

10,914,255

Strychnos alkaloids

322.407

2.2523

−3.304

4

1

41.57

2

0.29114

19,20-Dihydroakuammicine

11,023,792

Alkaloids and derivatives

324.423

2.3452

−3.568

4

1

41.57

3

2.1615

Lochnericine

11,382,599

Aspidospermatan-type alkaloids

352.433

1.5996

−3.538

5

1

54.1

3

2.3885

3-Isoajmalicine

11,416,867

Yohimbine alkaloids

352.433

2.2674

−3.141

5

1

54.56

2

2.6043

Vindolidin

11,618,751

Plumeran-type alkaloids

426.511

1.3936

−3.098

7

1

79.31

5

3.2845

Vincapusine

11,646,359

Alkaloids and derivatives

368.432

2.6409

−2.695

6

1

63.93

3

2.2856

Epibubbialine

11,830,997

Azaspirodecane derivatives

221.255

−0.1874

−1.424

4

1

49.77

0

1.6204

Vindoline

11,953,805

Plumeran-type alkaloids

456.537

1.3236

−3.116

8

1

88.54

6

3.2845

1,2-Dihydrovomilenine

11,953,964

Ajmaline-sarpagine alkaloids

352.433

1.8244

−3.654

5

2

61.8

2

1.1872

Pericyclivine

11,969,544

Macroline alkaloids

322.407

2.8635

−3.038

4

1

45.33

2

0.20237

Lycoctonine

11,972,492

Prenol lipids

467.601

−0.1645

−1.824

8

3

100.85

6

0.56009

Cathanneine

12,302,545

Aspidospermatan-type alkaloids

426.511

1.3713

−3.408

7

0

68.31

5

2.5051

Anahygrine

12,306,778

Alkaloids and derivatives

224.347

1.3823

−1.852

3

1

32.34

4

3.0573

Tabernaemontanin

12,309,360

Vobasan alkaloids

354.448

2.6197

−3.678

5

1

62.4

3

3.1533

4-Methoxynorsecurinine

101,091,319

Pyrrolizidines

233.266

−0.0349

−1.324

4

0

38.77

1

1.5563

Akuammicine

101,281,350

Strychnos alkaloids

322.407

2.2523

−3.304

4

1

41.57

2

0.87991

Heterophyllisine

101,289,617

Quinolidines

375.507

1.5254

−3.175

5

1

59

2

4.4531

Germacranolide

101,616,641

Prenol lipids

266.336

2.1659

−2.371

4

2

66.76

0

1.5629

Isoajmaline

101,624,670

Ajmaline-sarpagine alkaloids

326.438

1.791

−3.484

4

2

46.94

1

3.4513

Hetidine

101,685,340

Prenol lipids

357.448

0.8838

−2.601

5

2

77.84

0

2.8009

Catharosine

101,686,461

Plumeran-type alkaloids

384.474

0.909

−2.688

6

2

73.24

3

3.3742

Fluorocarpamine

101,688,177

Carboxylic acids and derivatives

339.414

1.8706

−3.095

5

1

58.64

2

0.97774

Ajmalicidine

101,927,009

Indoles and derivatives

370.447

3.0403

−3.438

6

1

63.93

2

2.2403

Hetisinone

101,930,090

Prenol lipids

327.423

1.0959

−2.903

4

2

60.77

0

0.86256

Rhazimol

101,986,486

Corynanthean-type alkaloids

338.406

0.2205

−2.55

5

2

73.13

2

2.6104

18-Hydroxy-3-epi-alpha-yohimbine

102,004,710

Yohimbine alkaloids

370.447

1.4991

−2.666

6

3

85.79

2

2.3334

Sarpagine

102,090,391

Macroline alkaloids

310.396

2.4395

−2.632

4

3

59.49

1

2.0345

Velbanamine

102,399,433

Indoles and derivatives

298.428

3.3453

−3.206

3

2

39.26

1

3.5116

Catharosine

2564–23-0

Plumeran-type alkaloids

384.474

0.909

−2.688

6

2

73.24

3

3.3742

3.2 Top ranked lead molecules for SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro from a set of phytochemicals and FDA approved drugs:

The top five leads-102004710 (18-Hydroxy-3-epi-alpha-yohimbine), 120,716 (Alloyohimbine), 10,308,017 (Gummadiol), 156798–15-1 (Asparagamine A) and 11,646,359 (Vincapusine) for SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro obtained using molecular docking studies of phytochemicals showed binding energies of −8.1 kcal/mol, −8.0 kcal/mol, −7.8 kcal/mol, −7.6 kcal/mol and −7.5 kcal/mol respectively. Molecular docking of FDA approved antiviral drugs yielded top 5 lead molecules-DB06290 (Simeprevir), DB09027 (Ledipasvir), DB09297 (Paritaprevir), DB13879 (Glecaprevir) and DB09102 (Daclatasvir) which showed binding energies of −9.7 kcal/mol, −9.3 kcal/mol, −9.3 kcal/mol, −9.3 kcal/mol and −9.2 kcal/mol respectively. The control α-ketoamide 13a inhibitor (O6K) displayed binding energy of −7.2 kcal/mol. All the lead compounds showed stable interactions with the target through a good number of hydrogen bonds as well as hydrophobic interactions except for 156798–15-1 (Asparagamine A) which exhibited only hydrophobic interactions. Interestingly, compared to the phytochemicals the FDA-approved antiviral drugs showed higher binding affinities to the target. Further, the lead molecules-10308017 (Gummadiol), 11,646,359 (Vincapusine) and DB13879 (Glecaprevir) showed the potential antiviral activity through hydrogen bond interactions with either His41 or Cys145, both of the residues constitute the catalytic dyad of SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro enzyme.

3.3 Top ranked lead molecules for SARS-CoV 3CLpro from a set of phytochemicals and FDA approved drugs:

Among the phytochemicals, top 5 leads-120716 (Alloyohimbine), 10,308,017 (Gummadiol), 11,646,359 (Vincapusine), 82178-34-5 (Arjunolone), 102,004,710 (18-Hydroxy-3-epi-alpha-yohimbine) showed binding energies of −9.0 kcal/mol, −8.4 kcal/mol, −8.3 kcal/mol, −8.1 kcal/mol and −8.0 kcal/mol respectively. Using molecular docking of FDA approved antiviral drugs, top 5 leads-DB13879 (Glecaprevir), DB13878 (Pibrentasvir), DB01072 (Atazanavir), DB09102 (Daclatasvir) and DB11574 (Elbasvir) were shortlisted which displayed binding energies of −9.7 kcal/mol, −9.3 kcal/mol, −9.2 kcal/mol, −9.2 kcal/mol and −8.8 kcal/mol respectively. The molecular binding between these lead compounds and the target is strengthened by a good number of hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions. The leads which displayed hydrogen bond interactions with the catalytic residues-His41 and Cys145 include DB13879 (Glecaprevir), DB11574 (Elbasvir), 10,308,017 (Gummadiol) and 102,004,710 (18-Hydroxy-3-epi-alpha-yohimbine). The control, SG85 inhibitor (G85) showed binding energy of −8.0 kcal/mol with the enzyme target.

3.4 Top ranked lead molecules for MERS-CoV 3CLpro from a set of phytochemicals and FDA approved drugs:

Few lead compounds were also identified for MERS-CoV 3CLpro using molecular docking of phytochemicals and the binding energies of top 5 leads-11646359 (Vincapusine), 120,716 (Alloyohimbine), 10,308,017 (Gummadiol), 11,969,544 (Pericyclivine) and 28,288,759 (Vidolicine) were −9.8 kcal/mol, −8.6 kcal/mol, −8.4 kcal/mol, −8.4 kcal/mol and −8.3 kcal/mol respectively. Among, the FDA approved antiviral drugs, the top 5 leads-DB01072 (Atazanavir), DB06817 (Raltegravir), DB09296 (Ombitasvir), DB08864 (Rilpivirine) and DB09297 (Paritaprevir) scored binding energies of −9.1 kcal/mol, −9.1 kcal/mol, −9.0 kcal.mol, −8.7 kcal/mol and −8.7 kcal/mol respectively. The control, GC813 inhibitor (AW4) showed binding energy of −8.0 kcal/mol. All the lead compounds established both a good number of hydrogen bonds as well as hydrophobic interactions with the target except 28,288,759 which exhibited only hydrophobic interactions. The lead molecules-DB06817 (Raltegravir), 120,716 (Alloyohimbine) and 11,969,544 (Pericyclivine) established hydrogen bond interactions with either His41 or Cys148 or both (catalytic dyad) which may explain their mode of inhibition against the enzyme target.

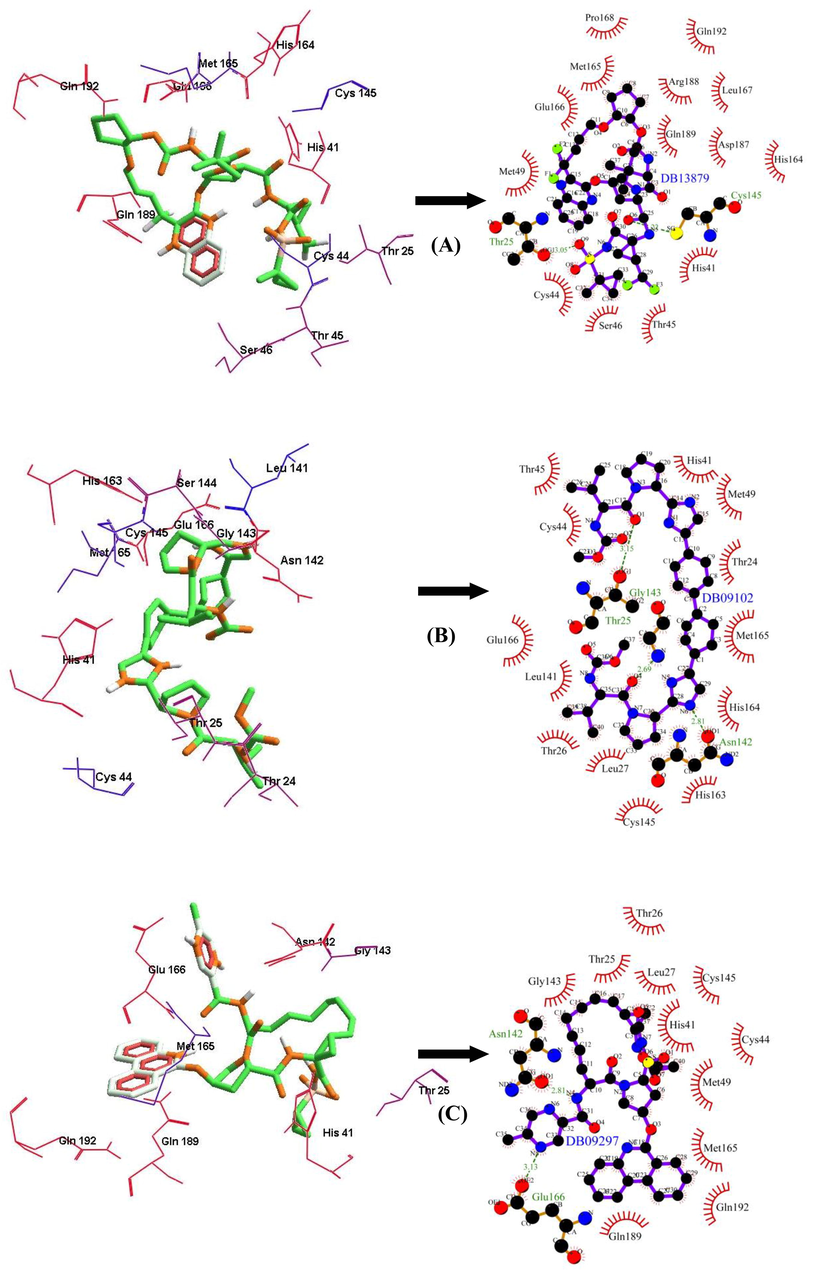

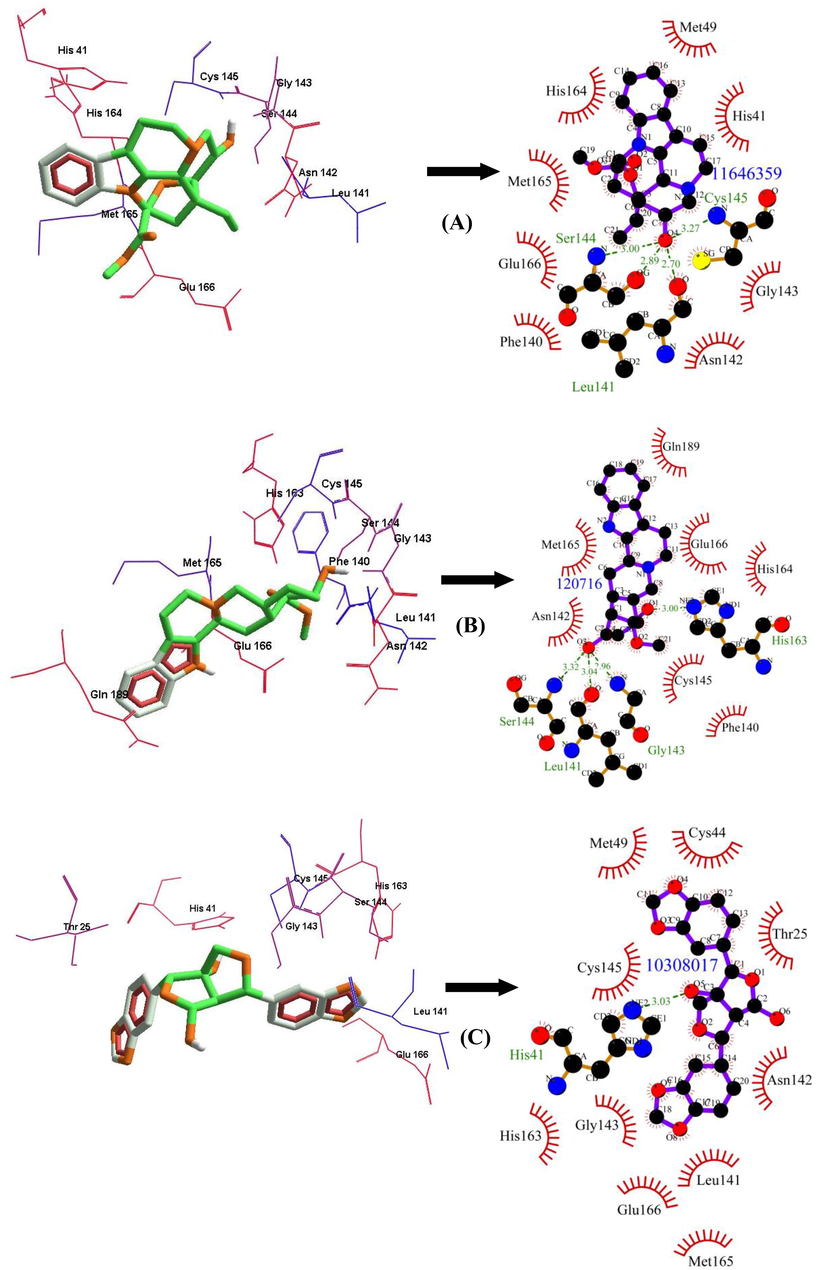

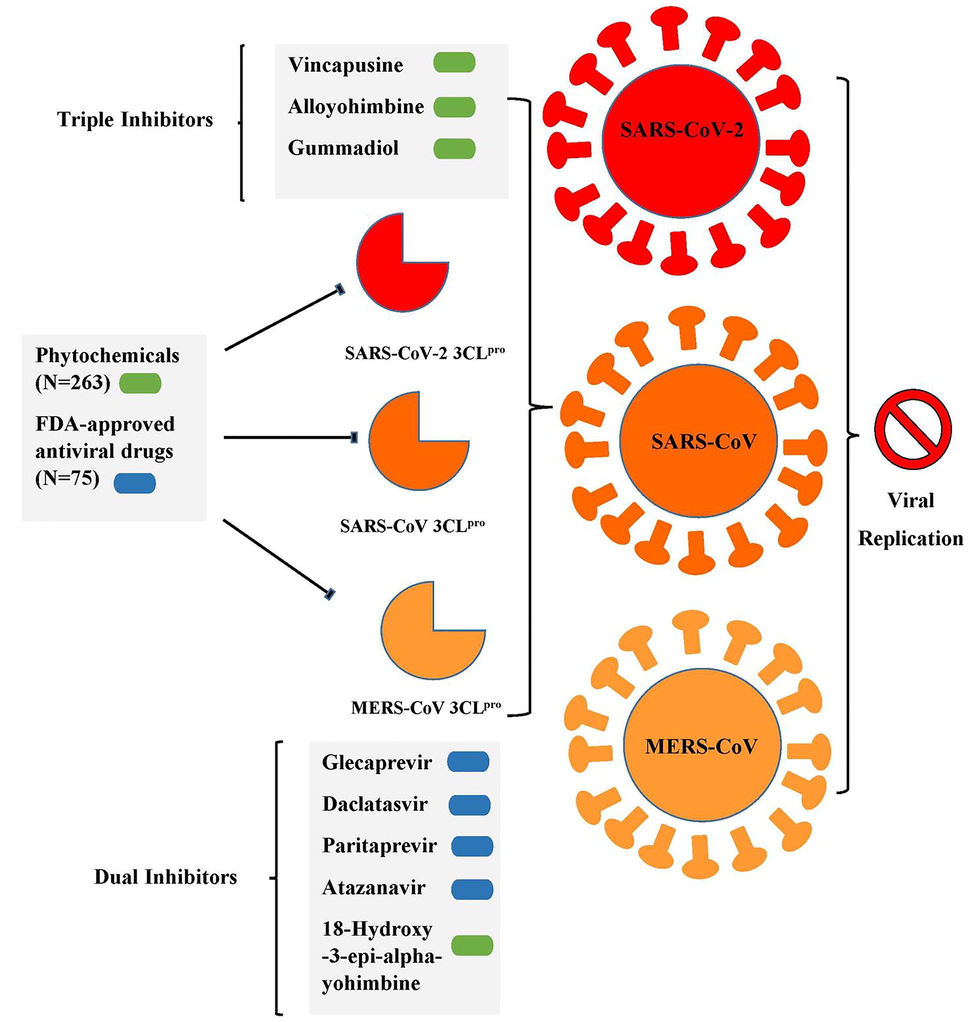

3.5 Common lead molecules as potential dual or triple inhibitors of the enzyme targets

Among the FDA approved antiviral drugs, we found that DB13879 (Glecaprevir) and DB09102 (Daclatasvir) can be potential leads for dual inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro (Fig. 1A, B) and SARS-CoV 3CLpro as they were common top 5 leads. The lead molecule DB09297 (Paritaprevir) can be explored as a dual inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro (Fig. 1C) and MERS-CoV 3CLpro and DB01072 (Atazanavir) can be used as an inhibitor for dual inhibition of SARS-CoV 3CLpro and MERS-CoV 3CLpro. While Glecaprevir, Daclatasvir and Paritaprevir have been used against chronic hepatitis C (For the Study of the Liver (KASL, K.A., others, 2018; Hézode, 2018), Atazanavir (HIV-1 protease inhibitor) is primarily used for the treatment of HIV infection (Eckhardt and Gulick, 2017). Interestingly, we found that the phytochemicals 11,646,359 (Vincapusine), 120,716 (Alloyohimbine) and 10,308,017 (Gummadiol) were common top 5 leads among the three targets and therefore, these phytochemicals can be used as triple inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro (Fig. 2A–C), SARS-CoV 3CLpro and MERS-CoV 3CLpro. The phytochemical 102,004,710 (18-Hydroxy-3-epi-alpha-yohimbine) was identified to be a potential dual inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro and SARS-CoV 3CLpro. Vinacapusine is a β-amino alcohol-type alkaloid extracted from leaves of Catharanthus pusillus, a traditional medicinal plant of India believed to possess oncolytic properties (Khare, 2007). Gummadiol belongs to the class of Furanoid lignans which can be extracted from Gmelina arborea (Anjaneyulu et al., 1975; Pathala et al., 2015). Alloyohimbine and 18-Hydroxy-3-epi-alpha-yohimbine are alkaloids which are isomeric forms of yohimbine, an alkaloid extracted from the bark of the tree Pausinystalia yohimbe and has been traditionally used for the treatment of sexual disorders (Anadón et al., 2016). However, the bioactivity of these compounds against viral infections have not been reported till date to the best of our knowledge and therefore these are novel phytochemical leads which could be further explored against coronavirus infections in humans. The key findings from the present study has been illustrated with Fig. 3.

The binding poses and LigPlot + results showing molecular interaction between SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro and lead molecules-(FDA approved antiviral drugs) (A) DB13879 (Glecaprevir) (B) DB09102 (Daclatasvir) (C) DB09297 (Paritaprevir). The hydrophobic interacting residues are indicated by red arcs with spikes and the green dashed lines with the bond distance correspond to hydrogen bonds.

The binding poses and LigPlot + results showing molecular interaction between SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro and lead molecules-(Phytochemicals) (A) 11,646,359 (Vincapusine) (B) 120,716 (Alloyohimbine) (C) 10,308,017 (Gummadiol). The hydrophobic interacting residues are indicated by red arcs with spikes and the green dashed lines with the bond distance correspond to hydrogen bonds.

A graphical summary illustrating the key findings from the present study.

4 Conclusion

The present work is an in silico attempt to propose lead molecules as potential inhibitors of coronavirus 3CLpro enzyme. Our study unravels new chemical entities from a repertoire of phytochemicals and FDA approved drugs that could be repurposed for treatment of coronavirus infection in humans. The leads suggested from this study could offer new candidate molecules in the drug discovery pipeline for the treatment and management of the disease. The current work is limited by small datasets and therefore, it would be worth exploring new chemical databases with big ligand sets for virtual screening procedure for identification of novel inhibitors against the target enzyme. A combined molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation approach could be envisaged which would further provide useful mechanistic insights into the binding modes of inhibitions at the atomic level. Further research work is necessary to establish the inhibitory activity of the identified FDA approved lead molecules against the coronavirus 3CLpro enzyme through in vitro and in vivo experiments.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to extend their sincere appreciation to the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSP-2019/154), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. J. Lee thanks to Chungnam National University, Daejeon, Republic of Korea for the funding support. The authors thank the Deanship of Scientific Research and RSSU at King Saud University for their technical support.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Recent progress and challenges in drug development against COVID-19 coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2)-an update on the status. Infect. Genet. Evol.. 2020;83:104327

- [Google Scholar]

- Anadón, A., Martínez-Larrañaga, M.R., Ares, I., Martínez, M.A., 2016. Chapter 60 - Interactions between Nutraceuticals/Nutrients and Therapeutic Drugs, in: Gupta, R.C. (Ed.), Nutraceuticals. Academic Press, Boston, pp. 855–874. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-802147-7.00060-7.

- The structure of gummadiol-a lignan hemi-acetal. Tetrahedron Lett.. 1975;16:1803-1806.

- [Google Scholar]

- The primary structure and expression of the second open reading frame of the polymerase gene of the coronavirus MHV-A59; a highly conserved polymerase is expressed by an efficient ribosomal frameshifting mechanism. Nucleic Acids Res.. 1990;18:1825-1832.

- [Google Scholar]

- Brian, D.A., Baric, R.S., 2005. Coronavirus genome structure and replication, in: Coronavirus Replication and Reverse Genetics. Springer, pp. 1–30.

- Origin and evolution of pathogenic coronaviruses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol.. 2019;17:181-192.

- [Google Scholar]

- COVID-19, an emerging coronavirus infection: advances and prospects in designing and developing vaccines, immunotherapeutics, and therapeutics. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2020:1-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Eckhardt, B.J., Gulick, R.M., 2017. 152 - Drugs for HIV Infection, in: Cohen, J., Powderly, W.G., Opal, S.M. (Eds.), Infectious Diseases (Fourth Edition). Elsevier, pp. 1293-1308.e2. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-7020-6285-8.00152-0.

- For the Study of the Liver (KASL, K.A., others, 2018. 2017 KASL clinical practice guidelines management of hepatitis C: Treatment of chronic hepatitis C. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 24, 169-229.

- Molecular evolution of human coronavirus genomes. Trends Microbiol.. 2017;25:35-48.

- [Google Scholar]

- Gorbalenya, A.E., 2001. Big nidovirus genome, in: The Nidoviruses. Springer, pp. 1–17.

- A decade after SARS: strategies for controlling emerging coronaviruses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol.. 2013;11:836-848.

- [Google Scholar]

- Merck molecular force field. I. Basis, form, scope, parameterization, and performance of MMFF94. J. Comput. Chem.. 1996;17:490-519.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Inhibition of SARS-CoV 3CL protease by flavonoids. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem.. 2020;35:145-151.

- [Google Scholar]

- Khare, C.P., 2007. Vinca pusilla Murr., in: Khare, C.P. (Ed.), Indian Medicinal Plants: An Illustrated Dictionary. Springer New York, New York, NY, p. 1. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-70638-2_1743.

- Genetic diversity of coronaviruses in bats in Lao PDR and Cambodia. Infect. Genet. Evol.. 2017;48:10-18.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lai, M.M.C., 2001. Coronaviridae: the viruses and their replication. In Fields Virology, Fourth Edition (Knipe DM, Howley PM, eds), Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia, pp. 1163–1185.

- LigPlot+: multiple ligand-protein interaction diagrams for drug discovery. J. Chem. Inf. Model.. 2011;51:2778-2786.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The complete sequence (22 kilobases) of murine coronavirus gene 1 encoding the putative proteases and RNA polymerase. Virology. 1991;180:567-582.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lead- and drug-like compounds: the rule-of-five revolution. Drug Discov. Today. Technol.. 2004;1:337-341.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- IMPPAT: A curated database of I ndian M edicinal P lants, P hytochemistry A nd T herapeutics. Sci. Rep.. 2018;8:1-17.

- [Google Scholar]

- AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J. Comput. Chem.. 2009;30:2785-2791.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Structures of the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus 3C-like protease reveal insights into substrate specificity. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr.. 2015;71:1102-1111.

- [Google Scholar]

- Vaccines for SARS-CoV-2: lessons from other coronavirus strains. Infect. Dis. Ther.. 2020;9:255-274.

- [Google Scholar]

- A review on gambhari (Gmelina arborea Roxb.) J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem.. 2015;4:127-132.

- [Google Scholar]

- DataWarrior: an open-source program for chemistry aware data visualization and analysis. J. Chem. Inf. Model.. 2015;55:460-473.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bat coronavirus in Brazil related to appalachian ridge and Porcine epidemic diarrhea viruses. Emerg. Infect. Dis.. 2015;21:729-731.

- [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiology, genetic recombination, and pathogenesis of coronaviruses. Trends Microbiol.. 2016;24:490-502.

- [Google Scholar]

- AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem.. 2010;31:455-461.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Molecular properties that influence the oral bioavailability of drug candidates. J. Med. Chem.. 2002;45:2615-2623.

- [Google Scholar]

- Coronavirus pathogenesis and the emerging pathogen severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev.. 2005;69:635-664.

- [Google Scholar]

- DrugBank: a knowledgebase for drugs, drug actions and drug targets. Nucleic Acids Res.. 2008;36:D901-D906.

- [Google Scholar]

- Discovery of seven novel Mammalian and avian coronaviruses in the genus deltacoronavirus supports bat coronaviruses as the gene source of alphacoronavirus and betacoronavirus and avian coronaviruses as the gene source of gammacoronavirus and deltacoronavi. J. Virol.. 2012;86:3995-4008.

- [Google Scholar]

- A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature. 2020;579:265-269.

- [Google Scholar]

- A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579:270-273.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ziebuhr, J., 2005. The coronavirus replicase, in: Coronavirus Replication and Reverse Genetics. Springer, pp. 57–94.

- The autocatalytic release of a putative RNA virus transcription factor from its polyprotein precursor involves two paralogous papain-like proteases that cleave the same peptide bond. J. Biol. Chem.. 2001;276:33220-33232.

- [Google Scholar]