Translate this page into:

Some common West African spices with antidiabetic potential: A review

⁎Corresponding author. oguntibejuo@cput.ac.za (Oluwafemi O. Oguntibeju)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Abstract

Diabetes is a chronic metabolic disorder of glucose metabolism, which is associated with an elevated level of glucose (hyperglycemia) in the blood. The unhealthy eating habit of people, obesity, inactivity and irregular use of diabetes prescribed medications are one of the factors that have increased the prevalence of diabetes worldwide. However, the high cost of managing diabetes and adverse effects associated with the use of synthetic drugs have impelled the quest to search for cost-effective and safer alternative antidiabetic agents. Conversely, spices are added to food to improve their taste, color, flavor, and shelf-life; they also possess some therapeutic values including antidiabetic activity due to the presence of bioactive components. As a result, the present review focuses on some commonly used spices in Africa that have demonstrated antidiabetic activity in both in vitro and in vivo studies, thereafter, we highlighted some bioactive compounds in these spices and their possible mechanism of action.

Keywords

West African spices

Antidiabetic activity

Bioactive compounds

Diabetes mellitus

- K+-ATP

-

Potassium-Adenosine triphosphate

- LD50

-

Median lethal dose

- HDL

-

High density lipoprotein

- LDL

-

Low density lipoprotein

- WHO

-

World Health Organization

Abbreviations

1 Introduction

Diabetes mellitus is a metabolic disorder characterized by derangement of glucose, protein, and lipid metabolism, which consequently leads to an elevated level of glucose (hyperglycemia) in the blood (American Diabetes Association, 2009). Besides hyperglycemia, other conditions such as polyurea, weight loss, muscle weakness, polydipsia, polyphagia, and hyperlipidemia are also associated with diabetes. Insulin inhibits the activity of hormones stimulating lipase in the adipose tissue. In the absence of insulin or during insulin resistance by receptors, the rate of lipolysis increases, thereby releasing free fatty acids into the bloodstream, this also increases β-oxidation of fatty acids and cholesterol production. Insulin also mediates the removal of cholesterol; hence, its absence leads to the manifestation of hyperlipidemia and hypercholesterolemia in diabetes (Sheikh et al., 2013). World Health Organization (WHO) statistics show that 400 million people worldwide have diabetes with about 1.5 million deaths and there is a projection of this rate doubling by 2035 due to the affluent lifestyle of people (Mohammed et al., 2015; Okoduwa et al., 2017). People with fasting blood sugar greater than 126 mg/dL or 7.0 mmol/L or random blood sugar greater than 200 mg/dL (11.1 mmol/L) are said to be diabetic.

Diabetes can be a result of a deficiency of insulin as in type I (childhood-onset) diabetes which is mainly caused by an autoimmune disease that depletes beta cells in the pancreas which produce insulin. This accounts for 10% of the type of diabetic population (Papitha et al., 2018), while type II which is a more prevalent form of diabetes is a result of the insensitivity of the receptors to insulin, it is common in middle-aged adult with obesity (Pereira et al., 2019). Some pregnant women usually in their third trimester can experience the disorder in glucose metabolism, this is often referred to as gestational diabetes, and this condition may get better or disappear after they deliver their babies. Diabetes can be due to hereditary, immune response, age, lifestyle, and stress (Bihari et al., 2011).

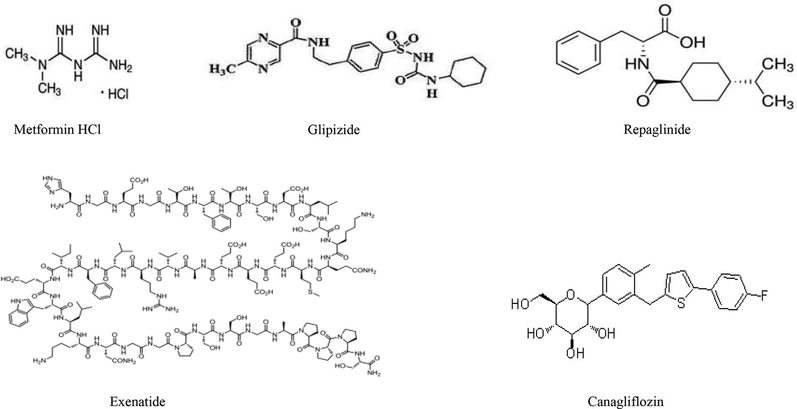

If the blood sugar level is not regulated it can have a serious impact on several organs and consequent lead to diseases such as hypertension, kidney disease, blindness. The cost of treating diabetes is expensive; it also comes with deleterious side effects such as weight gain, gastro disorder. Besides, people find it difficult to adjust to lifestyle modifications such as eating food that is not rich in sugar. Hence, it is important to look for alternative means of regulating blood sugar Figs. 1 and 2.

Chemical structure of some drugs used for managing diabetes.

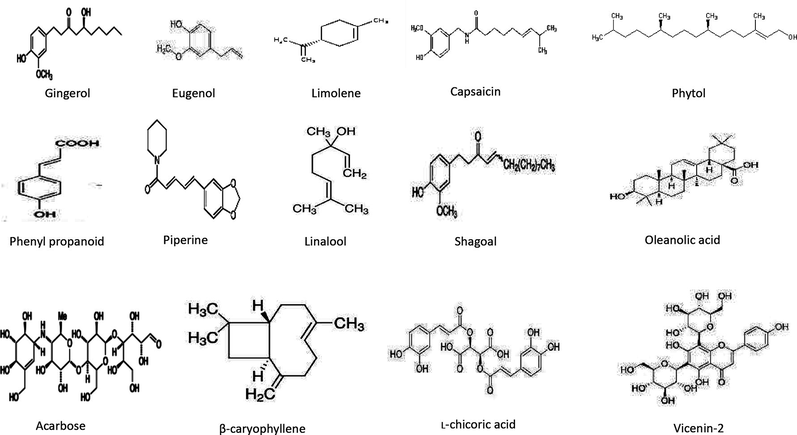

Some African food spices with antidiabetic activity.

Spices are usually added to food to improve their taste, color flavor, and shelf life, they often have medicinal values too due to the presence of bioactive components in them (Dzoyem et al., 2014; Tamokou et al., 2017). Unlike synthetic antidiabetic drugs that are not mostly convenient to be taken orally by many people, spices do not require a strict regimen as they can be taken as a food supplement, tea, or oil and are easily available and cheap with little or no side effects. Flavonoids, alkaloids, terpenoids, coumarins, sulphur compounds, peptides, amines, steroids, and sometimes complex carbohydrates have been reported to possess antidiabetic potentials (Ogbonnia and Anyakora, 2009). The various mechanisms by which plant drugs demonstrated antidiabetic activities include; glycosidase (glucosidase) inhibitor, α-amylase inhibition, inhibition of hepatic glucose metabolizing enzyme, stimulation of insulin production or acting as insulin mimic, glycogenesis stimulation, reducing the release of glucagon and other hormones that counterbalance the action of insulin, antioxidant mechanism, prevention of glycosylation of haemoglobin, and regulation of glucose absorption from the gut (Ogbonnia and Anyakora, 2009).

Antidiabetic potentials of several spices have been reported in the developed countries and as a result, this study aimed to evaluate the antidiabetic potentials of common spices used in African countries. Alloxan and streptozotocin are the common drugs used for inducing diabetes in animal models. They damage/destroy β-cell of the pancreas due to their cytotoxic nature thereby decreasing insulin production leading to type 1 diabetes and consequently decrease the usage of glucose by tissues, thereby leading to its elevated level in the blood (Sheikh et al., 2013). They can also be used to induce type 2 diabetes if calculated doses are used to cause partial destruction (deformation) of the pancreatic β–cells (Oguanobi et al., 2012). Some examples of drugs and the structure of compounds found in the drugs used in managing diabetes are enlisted in Table 1.

Drugs

Mechanism

Side effect

Metformin (Glucophage)

Inhibits glucose production by the liver thereby making the body to be sensitive to insulin

Causes nausea and diarrhea

Sulfonylureas (glyburide, glipizide glimepiride)

Stimulates the pancreas to produce more insulin

Cause hypoglycemia and unnecessary weight gain

Meglitinides (prandin and starlix)

Stimulating the body to produce more insulin, faster effect

Cause hypoglycemia and weight gain

GLP-1 receptor agonists (exenatide, liraglutide and semaglutide)

Injectable drugs that lower blood glucose by slowing down digestion

Joint pain and high risk of pancratitis

SGLT2 inhibitor (canagliflozin, dapagliflozin and empagliflozin)

Blood glucose by preventing reabsorbtion of glucose by the kidney

Low blood pressure, urinary tract infection.

Insulin

Hormone that converts glucose to glycogen (storage form of glucose)

Can often lead to hypoglycemia (low blood sugar)

2 Spices with antidiabetic potentials

2.1 Alligator pepper

Alligator pepper or Mbongo spice or Hepper pepper or Guinea pepper or Grain of paradise is scientifically known as Aframomum melegueta. In Nigeria, it is called Atare in Yoruba, Chitta in Hausa, Ose-oji in Igbo (Onoja et al., 2014). In Ghana, it is called Efom wisa, it belongs to the ginger family, Zingiberaceae; it is an herbaceous perennial plant that is widely distributed in swampy areas of western and central Africa (Lawal et al., 2015; Osuntokun, 2020). The fruit contains several tiny indehiscent seeds with a strongly aromatic and pungent smell. The seed is commonly used in preparing pepper soup (as fondly called in West Africa) due to its spicy nature; it is also used as a spice for meats, sauces, and soups (Kokou et al., 2013; Osuntokun, 2020). Its various medicinal values such as anti-inflammatory, aphrodisiac, hepatoprotective, antitumour, antidiabetic, antiulcer, anti-venom, antimicrobial, weight loss, erythropoietic potential, and many other medicinal uses have been reported in the literature (Adesokan et al., 2010; Mojekwu et al., 2011; Onoja et al., 2014; Lawal et al., 2015; Amadi et al., 2016). Phytochemical screening of alligator pepper has revealed the presence of secondary metabolites such as flavonoids, phenolic compounds, alkaloids, tannins, terpenoids, saponins, and cardiac glycosides in the seeds (Onoja et al., 2014; Amadi et al., 2016). Aqueous extract of the seed has been documented to be rich in phenolic compounds, gingerols, acarbose, shogaols, eugenol, oleanolic acid, paradols, acarbose buplerol, (-)-arctigenin, 5-hydroxy-7-methoxyflavone and apigenin (Mohammed et al., 2015; Amadi et al., 2016). Adefegha et al. (2017) highlighted that oil of A. melegueta seed contained limonene, eugenol, eucalyptol, α-pinene, β-pinene, β-cadinene, β-caryophyllene, α-terpineol, germacrene. Adesokan et al. (2010) reported the antidiabetic potential of aqueous extract of A. melegueta in alloxan-induced diabetic rats. They reported that the 200 mg/kg of aqueous extract A. melegueta was able to restore blood sugar in diabetic rats within 6 days as against the 100 mg/kg metformin (reference drug) that took 14 days to demonstrate the same level of antidiabetic effect. Mohammed et al. (2015) found that 300 mg/kg of ethyl acetate fraction of A. melegueta restore elevated glucose concentration to normal and ameliorate diabetes-related parameter in streptozotocin-induced diabetic in the rats. Morakinyo et al. (2019) reported the efficacy of 200 mg/kg and 400 mg/kg of methanolic extract of A. melegueta in normalizing alloxan-induced hyperglycemia in albino rats. The extract competed better than 5 mg/kg glibenclamide, the reference drug used. The extract also exhibited little or no side effects within the four weeks of oral administration (Ilic et al., 2010). Adefegha et al. (2017) reported the antiglycemic potential of essential oil from A. melegueta seed. The oil exhibited in vitro inhibition of α-amylase and α-glucosidase, which are responsible for the breakdown of carbohydrates into glucose. They proposed that the synergistic effect of eugenol, limonene, α-pinene, and β-pinene in this oil was responsible for the antiglycemic effect.

2.2 West African black pepper

West African black pepper or Ashanti pepper or Guinea pepper is scientifically known as Piper guineense (Schum & Thonn), it belongs to the Piperaceae family, it is an herbaceous plant with elliptically shaped leaves and is distributed throughout the West Africa regions, it is also common in Guinea and Uganda (Okpala and Ekechi, 2014). In Nigeria, it is called Iyere in Yoruba, Uziza in Igbo, and Poivrie in French. The fruit (berry) of P. guineenseis used as a spice to add aroma, flavor, and hotness to soup (Owolabi et al., 2013). Various parts of the plants such as the roots, seeds, stem bark, and leaves are used in folk medicine. It is usually consumed by women in the southeastern part of Nigeria after childbirth to expel remains in the womb through uterine contraction and to enhance the flow of breast milk (Udoh et al., 1996). It is used as an aphrodisiac (Kpomah et al., 2012), hepatoprotective (Oyinloye et al., 2017), antioxidant, bronchitis, cough, stomachache (Owolabi et al., 2013), anticonvulsant, anticancer, antidiabetic (Khaliq et al., 2015), haematopoietic, antiulcer, rheumatism (Uhegbu et al., 2015), insecticidal (Ihemanma et al., 2014), antimicrobial (Mgbeahuruike et al., 2019). Alkaloids, flavonoids, amides, tannins, triterpenoids, polyphenols, cardiac glycosides, and saponins are the secondary metabolites found in P. guineense (Uhegbu et al., 2015; Ekoh et al., 2014). Essential oils of P. guineense fruit contains the following linalool, asaricin, β-caryophyllene, piperine, α-pinene, myrcene, 1,8-cineole, β-Ocimene, β-elemen, cedrene, elemol, elemicin, β-caryophyllene oxide, benzoic acid, sesquiterpene β-caryophyllene, bicyclogermacrene, humulene, monoterpenes β-pinene (Juliani et al., 2013; Owolabi et al., 2013). The constituent compounds obtained in P. guineense are dependent on the geographical location of where it is obtained. Ekoh et al. (2014) acknowledged the antihyperglycemic activity of 500 mg/kg of aqueous extract of P. guineense in alloxan-induced diabetic rats. Wodu et al. (2017) also reported antihyperglycaemic activity of methanolic extract of 100 mg/kg P. guineense in alloxan-induced diabetic female albino Wistar rats in a 14-day study. Their findings revealed that 50 and 100 mg/kg P. guineense normalize hyperglycemia in the rats better than 10 mg/kg of glibenclamide, which was the reference drug. Atal et al. (2012) isolated piperine, a major alkaloid found in the Piper genus; they reported that 20 mg/kg piperine restore normal blood glucose in alloxan-induced diabetic mice. Alkaloids have been reported to inhibit α-glucosidase and the transport of glucose to the epithelial cells in the intestine (Khaliq et al., 2015). Reports on toxicology and haematological evaluation by Uhegbu et al. (2015) in albino rats revealed that the plant has no toxic effects on the liver of the animals. They reported that it increased the haemoglobin content in the animal model; they proposed that the vitamins, minerals, and phytochemicals present in the plant were responsible for this haematopoeitic activity.

2.3 Ethiopian pepper

Ethiopian pepper is scientifically known as Xylopia aethiopica (Dunal), it belongs to the Annonaceae, and the species name aethiopica derived its name from Ethiopia, which is the origin of the tree, though it is now widely distributed in almost all parts of Western and Central Africa (Orwa et al., 2009). It is called Uda in Igbo and is commonly used in the southeastern part of Nigeria by women that are just put to bed to control bleeding (Johnkennedy et al., 2011). The fruit is popularly used as a spice in soup due to its aromatic pungent smell (Mohammed and Islam, 2017). It has been reported to possess antihelminthic (Ekeanyanwu and Etienajirhevwe, 2012), anti-rheumatism, anti-arthritis (Mohammed et al., 2015), antiproliferative, antioxidant (Adaramoye et al., 2017), hypolipidemic, antihypertensive, hepatoprotective (Adefegha et al., 2018), female fertility enhancement, antihemorrhoids (Yin et al., 2019), haematopoeitc (Johnkennedy et al., 2011), antimicrobial activities (Ogbonna et al., 2013). Various parts of the plants such as fresh and dried fruit, leaf, stem bark, root, and essential have been reported for their medicinal values (Ogbonna et al., 2013). Phytochemical analysis revealed the presence of alkaloids, flavonoids, glycosides, terpenoids, fats, and oil in X. aethiopica (Victor et al., 2013). Tegang et al. (2018) reported that the main compounds in the essential oil of X. aethiopica were β-pinene-pinene, α-phellandrene, Z-c-bisabolene and α-pinene, α-thujene, cis-β-ocimene, c-terpinene, oleanolic acid, kaurenoic, and xylopic acids. Papitha et al. (2018) reported the ability of ethanolic extract of X. aethiopica to normalize glucose concentration in streptozotocin-induced Sprague-Dawley male rats. They reported X. aethiopica competed favourably with metformin, the reference drug. Okpashi et al. (2014) reported the antidiabetic potential of 250 mg/kg of chloroform extract of X. aethiopica fruit. This study revealed that extracts did not only regulated blood glucose when compared to glibenclamide (control/standard drug) but also prevented hyperlipidemia, which is a complication that is characteristics of diabetes. They also reported that the extract was not toxic based on biochemical parameters investigated and that it displayed greater glucose regulating activity when combined with Psidium guajava leave extract. Ogbonnia et al. (2008) reported the hypoglycemic potential of X. aethiopica fruits and Astonia congensis mixture. They reported the safety of the acute administration of the mixture based on the biochemical parameters evaluated, however, their findings revealed that long-term use of the mixture could lead to kidney problems. Mohammed and Islam (2017) reported the ability of acetone fraction of X. aethiopica fruit in ameliorating oxidative stress in type 2 diabetic rats due to the high content of antioxidants in it. Ofusori et al. (2016) in their histological and immunohistochemical investigations reported that aqueous leaf extract of X. aethiopica aids recovery of β-cells of the pancreas and normalized glucose concentration in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Gometi et al. (2014) reported the non-toxic effect of chloroform extract of X. aethiopica based on liver marker enzymes investigated. Mohammed et al. (2019) found that oleanolic acid, an active antidiabetic compound isolated from X. aethiopica fruit inhibited α-glycosidase and α-amylase, molecular docking was also carried out on this compound and enzymes to confirm its antidiabetic potential. Famuyiwa et al. (2018) isolated kaurenoic and xylopic acids from X. aethiopica, they reported that 10 mg/kg kaurenoic and 20 mg/kg xylopic acids exhibited hypoglycemic effect; their investigation revealed that 20 mg/kg kaurenoic was safe and exhibited better glucose-lowering activity than to 5 mg/kg glibenclamide (the reference drug).

2.4 African chili

Red pepper or African chili or Bird chili is scientifically known as Capsicum frutescens, it belongs to the Solanaceae family. Its fruit is smaller but more spicy/pungent than Capsicum annum and it is widely cultivated in Africa and all over the world (Anthony et al., 2013). The unripe fruit is green, but it is red or orange when ripe, while the seeds are yellow in colour. It is used as a spice for adding hotness or heat to the soup. The fruit can be consumed fresh, or it can be dried and processed into powder, paste, and chopped pepper (Liu et al., 2020). Phytochemical screening of C. frutescens indicated that it contained flavonoids, alkaloids, terpenoids, tannins, and saponins (Izah et al., 2019; Maya et al., 2019). The fruit contains the following compounds δ-elemene, α-humelene, γ-himachalene, β–bisabolene, homocapsaicin, capsaicin, dihydrocapsaicin, vanillyl-nonanamide. The oil contains capsaicin and vitamin E. Al-Samydai et al. (2019) reported the presence of capsaicin, dihydrocapsaicin, tridecanoic acid, phytol, kauran-16-ol, eugenol and 1, 2-benzenedicarboxylic acid, mono (2-ethylhexyl) ester in acetone fraction of ethanolic extract of C. annuum fruit. Capsaicin is colourless, odourless, hydrophobic, and crystalline compound (Al-Samydai et al., 2019). The degree of hotness of the fruit/seed is dependent on the concentration of capsaicinoids in it. C. frutescens have been reported to possess anti-inflammatory, anticancer (Al-Samydai et al., 2019), antimicrobial (Doğan et al., 2018), hypertension (Anthony et al., 2013), antioxidant, antidiabetic, antianalgesic (Izah et al., 2019), hypolipidemia and cardioprotective activity (Lim, 2012).

Watcharachaisoponsiri et al. (2016) reported that 5 mg/mL ethanolic extract of C. frutescens inhibited α-glucosidase and α-amylase, which are key enzymes that hydrolyse polysaccharide to glucose, consequently preventing overload of glucose in the blood. Anthony et al. (2013) reported that the potential of C. frutescens supplemented diet to normalize fasting glucose concentration, body weight, lipid profile, and other biochemical parameters in alloxan-induced diabetic rats. Dougnon and Gbeassor (Dougnon and Gbeassor, 2016) reported the hypoglycemic effect of powder C. frutescens in rabbits. Islam and Choi (Islam and Choi, 2008) found that 2% of C. frutescens increased insulin concentration in streptozotocin-induced Sprague Dawley diabetic rats with no toxic effect at high dosage. Kim et al. (2018) reported that the extract of C. annum seed decreases gluconeogenesis in the liver, while it increased the usage of glucose by muscles in vitro. Magied et al. (2014) reported hypoglycemic activity of C. annum in alloxan-induced diabetic rats, which were also subjected to a high-fat diet. Their investigation revealed that capsaicin was responsible for this activity.

2.5 African nutmeg

African nutmeg or Calabash nutmeg is scientifically known as Monodora myristica, it is a flowering plant that belongs to the Annonaceae family and grows in the wild in many African countries (Okonji et al., 2014). It is called Ariwo or Abo Lakoshe in Yoruba, Uhuru in Igbo (Ukachukwu et al., 2012). The seed is used as a spice due to its aromatic flavor. Phytochemical screening of M. myristica extracts revealed that they contain alkaloids, tannins, saponins, flavonoids, flavonol, steroids, terpenoids, phenol, and glycosides (Dougnon and Ito, 2020). Dongmo et al. (2019) reported that the essential oil of M. myristica contains α-phellandrene (61.5 ± 5.1%), germacradienol (7.9 ± 0.6%), and δ-cadinene (4.2 ± 1.1%). Other medicinal uses such as antibacterial, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antidiabetic (Ukachukwu et al., 2012), antihypertensive (Dougnon and Ito, 2020), antiprotozoal, hyperlipidemia, cytotoxic, antiarthritis (Nwankwo, 2018) have established in the literature. Okonji et al. (2014) reported the antidiabetic potential of ethanolic extract of M. myristica seed based on its ability to inhibit pancreatic α-amylase, which is a key enzyme, involved in converting starch and glycogen to glucose. The inhibition of this enzyme delays the digestion of carbohydrates thereby decreasing the release and absorption of glucose subsequently offering a good strategy for the regulation of blood glucose. They reported 96.58% inhibition of pancreatic α-amylase at 1000 µg/mL (IC50 value 408.17 ± 2.945 µg/mL); the study further revealed that this inhibition is dose-dependent. In addition, they proposed that this inhibition might be due to the presence of flavonoids in this plant. Ademosun and Oboh (2015) also reported the inhibitory activity of aqueous M. myristica seed on α-amylase and α-glucosidase.

2.6 Pepper elder

Pepper elder is also known as a “Shiny bush” or “Silver bush” is scientifically known as Peperomia pellucida,it is an angiosperm plant that belongs to the Piperaceae family. The leaves and stem are succulent and are used as a spice for preparing food due to their aromatic nature and their ability to stimulate appetite and aid digestion. The plant is a weed with a tiny seed that grows in the wild in almost all parts of the world. It is called Rinrin or Renren among the Yorubas, Southwest of Nigeria (Alves et al., 2019). Flavonoids, alkaloids, saponin, sterols, tannins, reducing sugars, carotenoids and triterpenes are the major secondary metabolites reported to be present in P. pellucida (Sheikh et al., 2013; Sultana et al., 2016; Waty et al., 2017). Its essential oil contains predominantly monoterpenoid alcohols, sesquiterpenes, aromatic and aliphatic aldehydes (Okoh et al., 2017). Dillapiole, dill-apiol, pellucidatin, peperochromen-A, peperomin A, phenylpropanoids, myristicin, germacrene, carotol, pygmaein, piole, trans-3-pinanone, methylethylidenepropane dinitrile, linalool, limonene, apiole, phytol, β-caryophyllene, and linalyl acetate (Alves et al., 2019; Okoh et al., 2017). Antihemorrhagic wound dressing, antibacterial (Sheikh et al., 2013), anti-inflammatory, antioxidant (Hamzah et al., 2012), cytotoxic, antisickling, antihypertensive, immunostimulatory (Minh, 2019). Sheikh et al. (2013) reported the hypoglycemic effect of ethanolic extract of P. pellucida in alloxan-induced diabetic mice. Their investigation revealed that 250 mg/kg and 500 mg/kg significantly lowered glucose levels in diabetic mice in a dose-dependent manner when compared to metformin (the reference drug). The study revealed that the extract regenerated β-cell of the pancreas, thereby restoring insulin secretion and subsequently control of diabetics due to the presence of alkaloid, saponin, and flavonoid in the extract. They also found that the extract normalizes elevated lipid concentration in the blood. Sultana et al. (2016) also reported similar observations where the antidiabetic and antihyperlipidemic potential of various solvent partition extract of P. pellucida in alloxan-induced diabetic mice. They reported that chloroform extract gave the highest antidiabetic activity among the various solvents investigated. Furthermore, the safety of the extract at higher doses (500 mg/kg) was also documented. In another study carried out by Hamzah et al. (2012), the antidiabetic potential of P. pellucida supplemented diet in alloxan-induced diabetic rats was also reported. They revealed that 10% and 20% w/w supplement showed higher activity than the standard drug (glibenclamide 600 µg/kg). They proposed that the P. pellucida might have insulin-mimetic activity by closing Na+/K+-ATP channels and depolarizing membrane, consequently stimulating the influx of Ca2+. They also reported that the supplement ameliorated diabetes-induced oxidative stress and dyslipidemia. Waty et al. (2017) reported the safety of the methanolic extract of P. pellucida following acute administration in rats even at 4000 mg/kg (LD50 value is greater than 4000 mg/kg). Biochemical and histopathology investigations revealed that there was no significant difference between the liver and kidney of the control and that of the male and female mice given 4000 mg/kg of the extract.

2.7 African basil

African basil or scent leaf is scientifically known as Ocimum gratissimum, it belongs to the Labiaceae family. It is an herbaceous plant that is widely distributed in the savanna and tropical rainforest of West Africa (Oguanobi et al., 2012). In Nigeria, it is called “Efinrin” in Yoruba, “Nchanwu or Nehonwu” in Igbo, and “Daidoya or ai daya ta guda” in Hausa. It is commonly used as a spice for cooking due to it has a minty aromatic flavour (Okoduwa et al., 2017). Phytochemical screening revealed that O. gratissimum leaf contained alkaloids, glycosides, flavonoids, steroid glucosides, polyphenols, saponin, steroids, tannins, and terpenoids (Bihari et al., 2011). L-chicoric acid, eugenyl-β-d-glucopyranoside, linolenic acid, l-caftaric acid and vicenin-2 are the compounds responsible for the antidiabetic potential of O. gratissimum (Casanova et al., 2014). It has been reported to possess antimicrobial, antidiabetic, hypolipidemic, hepatoprotective, antidiarrhoeal, antiinflammatory, antihypertensive, antioxidant, and immunostimulatory potential (Makinwa et al., 2013). Oguanobi et al. (2012) reported the antidiabetic potential of aqueous extract of O. gratissimum in streptozotocin-induced type 2 diabetic in neonatal Wistar rats in a dose-dependent manner. Okoduwa et al. (2017) reported the antidiabetic potential of O. gratissimum leaf extract in rats using fortified diet-fed streptozotocin-model of inducing type 2 diabetes. They used n-hexane, chloroform, ethyl acetate, n-butanol, and water to fractionate the extract, their studies revealed that the n-butanol fraction had the highest antidiabetic activity. This study revealed that 250 mg/kg of n-butanol fraction O. gratissimum exhibited a higher hypoglycemic effect than 500 mg/kg metformin (the reference drug). Their acute toxicity study revealed that the extract is safe at 250 mg/kg, which was the minimum effective dosage; mortality and signs of toxicity were not experienced even at an extremely high dosage of 5000 mg/kg mortality. Their findings also revealed the hypolipidemia effect and ability of the plant extract to regenerate pancreatic β-cells. Mohammed et al. (2007) also reported the higher antidiabetic potential of 500 mg/kg aqueous leaves extract of O. gratissimum on blood glucose levels of streptozocin-induced diabetic Wistar rats than insulin (reference drug/hormone). Bihari et al. (2011) also reported the antidiabetic activity of O. gratissimum and other species in an alloxan-induced diabetic animal model. Their study showed that 250 mg/kg methanolic extract of O. gratissimum exhibited hypoglycemic effect that is comparable to glibenclamide (the standard drug). Casanova et al. (2014) reported that 3 mg/kg of chicoric acid, a compound isolated from O. gratissimum reduced hyperglycemia in diabetic mice by 50% in just 2 h of treatment by increasing insulin secretion by the β-cells of the pancreas by inhibiting protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B, an enzyme that negatively regulates insulin sensitivity.

2.8 African locust beans

African locust beans are scientifically known as Parkia biglobosa and it is a legume, which is a member of the Mimosaceae family (Odetola et al., 2006). In Nigeria, it is commonly known as “iru” in Yoruba, “ogiri” in Igbo, and “dadawa” in Hausa. Its fermented seed is usually used as a local condiment/seasoning commonly added to different kinds of soups to improve their taste (Sule et al., 2015). P. biglobosa is widely distributed in several African countries, especially in the savanna where it is being cultivated as food/source of nutrients, medicine, shade/shelter, a high source of income, and for improving soil fertility (Teklehaimanot, 2004). Its pulp is sweet and edible, while the seed (beans) is commonly processed as a seasoning. It is rich in protein, carbohydrates, lipids, fiber, and essential minerals (Sule et al., 2015). Traditionally, it is used for improving eyesight, healing wound, treating leprosy (Odetola et al., 2006), antidiabetes (Fred-Jaiyesimi and Abo, 2009), antihypertensive, antidiarrhoea (Ajaiyeoba, 2002), anti-snake venom (Asuzu and Harvey, 2003), analgesic (Kokou et al., 2013). Interestingly, their pharmacological uses such as antimicrobial (Ajaiyeoba, 2002), antihypertensive, antidiabetes, and antihyperlipidemia (Odetola et al., 2006) have been documented in the literature. The phytochemical screening of extracts of P. biglobosa revealed that it contains tannins, cardiac glycosides, flavonoids, polyphenols, saponin, steroids, and alkaloids (Ajaiyeoba 2002; Fred-Jaiyesimi and Abo 2009; Sunmonu and Lewu, 2019). Cis-ferulates, lupeol, gallocatechin, epi-catechin, and 3-O-gallat are the major compounds isolated from P. biglobosa tree bark (Tringali et al., 2000). Sule et al. (2015) reported the hypoglycemic potential of P. biglobosa seed supplemented diet in rats. Their investigation revealed that 40% locust bean seed significantly lowers (p < 0.05) blood glucose level within 7 days than the control group, while it took 20% locust bean seed supplemented diet between 14 and 21 days to exert the same effect in rats. Odetola et al. (2006) reported that 6 g/kg of aqueous and methanolic extract of P. biglobosa ameliorated alloxan-induced diabetes in rats. Their investigation revealed P. biglobosa competed favourably with the standard drug (glibenclamide) in normalizing blood sugar. They also reported that aqueous extract of P. biglobosa performed better than the methanolic extract and the standard drug in restoring weight loss in the diabetic rat. Their investigation revealed that the weight loss restoration and the lipid profile (high HDL and low LDL) of the rats treated with aqueous extract of P. biglobosa were like those of the normal control. Fred-Jaiyesimi and Abo (2009) reported the hypoglycemic potential of chloroform and hexane fractions of methanolic extract of P. biglobosa seed in glucose-loaded and alloxan-induced diabetic rats. Their investigation revealed that the chloroform fraction (1 g/kg) demonstrated significant antidiabetic potential than 5 mg/kg of glibenclamide (the standard drug). Ogunyinka et al. (2017) reported that P. biglobosa seed protein isolates ameliorated hepatic damage and oxidative stress in streptozotocin-diabetic male rats. Table 2 and Fig. 3 show some of the compounds isolated from spices with anti-diabetic potentials.

Compounds

Mechanism

References

Gingerol

Enhances glucose uptake, transport and translocation

(Li et al., 2012)

Regulates enzymes by decreasing gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis; while increasing glycogenesis

(Son et al., 2015)

Acarbose

Inhibits α-amylase and α-glucosidase

(Kumar et al., 2016)

Shogaols

Stimulates glucose utilization

(Wei et al., 2017)

Inhibition of advanced glycation end-product

(Nonaka et al., 2019)

Eugenol

Attenuates key enzymes of glucose metabolism

(Srinivasan et al., 2014)

Ameliorates insulin resistance, increases insulin production

(Al-Trad et al., 2019)

Inhibits α-glucosidase and prevents formation of advanced glycation end-product

(Singh et al., 2016)

Oleanolic acid

Improves insulin response by preserving and enhancing functionality of β-cells; activation of the transcription factor Nrf2

(Castellano et al., 2013)

Promote insulin signal transduction and inhibit insulin resistance

(Wang et al., 2011)

Inhibits glucose production and stimulates glucose utilization

(Zhang et al., 2014)

Linalool

Enhances glucose uptake

(More et al., 2014)

Piperine

Inhibits α-glucosidase

(Kumar et al., 2013)

PPAR-ƴ receptor agonist

(Kharbanda et al., 2016)

Capsaicin

Inhibits α‐glucosidase, α‐amylase, and tyrosinase

(Nanok and Sansenya, 2020)

Phenylpropanoids

Stimulates insulin secretion

(Krishnan et al., 2014)

Limolene

Regulates enzymes involved in carbohydrate metabolism, stimulates insulin secretion and prevents glycation of haemoglobin

(Murali and Saravanan, 2012; Habtemariam, 2018)

Phytol

activation of nuclear receptors and heterodimerization of RXR with PPARγ

(Elmazar et al., 2013)

β-caryophyllene

insulinotropic and β cell regeneration

(Basha and Sankaranarayanan, 2016; Kumawat and Kaur, 2020)

l-chicoric acid

Enhances insulin release and glucose uptake

(Tousch et al., 2008)

Vicenin-2

Inhibitsα-glucosidase, protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP1B), aldose reductase (RLAR), and prevents advanced glycation end products (AGE)

(Islam et al., 2014)

Chemical structure of compounds isolated from spices with antidiabetic potential.

3 Conclusions

Health is wealth, early management of diabetes will help to arrest complications associated with it and prevent various organs and tissues from unnecessary stress and damage. This study showed that numerous spices with antidiabetic potential abound on the continent of Africa. Several studies have shown that these spices demonstrated higher antidiabetic activity than the conventionally used antidiabetic drugs such as metformin and glibenclamide. Some bioactive compounds found in these spices have been developed into drugs in advanced countries. Several advantages are associated with the use of spices as an alternative antidiabetic agent. However, most of the studies carried out on the antidiabetic activity of spices have been based on in vitro and animal models; hence, there is a need for a clinical trial in human subjects. Furthermore, it will be interesting to study the effect of combining two or more of these spices in a polyherbal formulation to explore them for better efficacy and safety because each spice possesses different mechanisms of regulating blood sugar.

Author contribution statement

O.O.O., K.O. and R.I.A. conceptualized the review idea; K.O. and R.I.A. wrote the first draft of the manuscript; O.O.O. and K.O. proofread the manuscript; all authors approved the manuscript for submission.

Acknowledgement

The authors duly acknowledge Cape Peninsula University of Technology for their financial support.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Antioxidant and antiproliferative potentials of methanol extract of Xylopia aethiopica (Dunal) A. Rich in PC-3 and LNCaP cells. J. Basic Clin. Physiol. Pharmacol.. 2017;28(4):403-412.

- [Google Scholar]

- Dietary supplementation with Ethiopian pepper (Xylopia aethiopica) modulates angiotensin-I converting enzyme activity, antioxidant status and extenuates hypercholesterolemia in high cholesterol fed Wistar rats. Pharma Nutr.. 2018;6(1):9-16.

- [Google Scholar]

- Essential oil composition, antioxidant, antidiabetic and antihypertensive properties of two Afromomum species. J. Oleo Sci.. 2017;66(1):51-63.

- [Google Scholar]

- Inhibition of carbohydrate hydrolyzing enzymes associated with type 2 diabetes and antioxidative properties of some edible seeds in vitro. “Int. J. Diabetes Dev. Ctries.. 2015;35(3):516-521.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of hypoglycaemic efficacy of aqueous seed extract of Aframomum melegueta in alloxan-induced diabetic rats. Sierra Leone J. Biomed. Res.. 2010;2(2)

- [Google Scholar]

- Phytochemical and antibacterial properties of Parkia biglobosa and Parkia bicolor leaf extracts. Afr. J. Biomed. Res.. 2002;5(3)

- [Google Scholar]

- Qualitative and quantitative analysis of capsaicin from Capsicum annum grown in Jordan. Int. J. Res. Pharm. Sci.. 2019;10(4):3768-3774.

- [Google Scholar]

- Eugenol ameliorates insulin resistance, oxidative stress and inflammation in high fat-diet/streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat. Life sci.. 2019;216:183-188.

- [Google Scholar]

- The chemistry and biological activities of Peperomia pellucida (Piperaceae): A critical review. J. Ethnopharmacol.. 2019;232:90-102.

- [Google Scholar]

- Research progress in phytochemistry and biology of Aframomum species. Pharm. Biol.. 2016;54(11):2761-2770.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(Supplement 1):S62-S67.

- [Google Scholar]

- Regulated effects of Capsicum frutescens supplemented diet (CFSD) on fasting blood glucose level, biochemical parameters and body weight in alloxan induced diabetic wistar rats. J. Pharm. Res. Int. 2013:496-507.

- [Google Scholar]

- The antisnake venom activities of Parkia biglobosa (Mimosaceae) stem bark extract. Toxicon.. 2003;42(7):763-768.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of the effect of piperine per se on blood glucose level in alloxan-induced diabetic mice. Acta Pol. Pharm.. 2012;69(5):965-969.

- [Google Scholar]

- β-Caryophyllene, a natural sesquiterpene lactone attenuates hyperglycemia mediated oxidative and inflammatory stress in experimental diabetic rats. Chem. Biol. Interact.. 2016;245:50-58.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phytochemical investigation & evaluation for antidiabetic activity of leafy extracts of various Ocimum (Tulsi) species by alloxan induced diabetic model. J. Pharm. Res.. 2011;4:28-29.

- [Google Scholar]

- Identification of chicoric acid as a hypoglycemic agent from Ocimum gratissimum leaf extract in a biomonitoring in vivo study. Fitoterapia. 2014;93:132-141.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biochemical basis of the antidiabetic activity of oleanolic acid and related pentacyclic triterpenes. Diabetes. 2013;62(6):1791-1799.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antibacterial effect of hot peppers (Capsicum annuum, Capsicum annuum var globriusculum, Capsicum frutescens) on Some Arcobacter, Campylobacter and Helicobacter species. Pak. Vet. J.. 2018;38(3)

- [Google Scholar]

- Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of essential oils from Aframomum citratum, Aframomum daniellii, Piper capense and Monodora myristica. J. Med. Plant Res.. 2019;13(9):173-187.

- [Google Scholar]

- Medicinal uses, thin-layer chromatography and high-performance liquid chromatography profiles of plant species from Abomey-Calavi and Dantokpa Market in the Republic of Benin. J. Nat. Med.. 2020;74(1):311-322.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of the effects of the powder of Capsicum frutescens on glycemia in growing rabbits. Vet. World. 2016;9:281.

- [Google Scholar]

- The 15-lipoxygenase inhibitory, antioxidant, antimycobacterial activity and cytotoxicity of fourteen ethnomedicinally used African spices and culinary herbs. J. Ethnopharmacol.. 2014;156:1-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- In vitro anthelmintic potentials of Xylopia aethiopica and Monodora myristica from Nigeria. Afr. J. Biomed. Res.. 2012;6(9):115-120.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anti-hyperglycemic and anti-hyperlipidemic effect of spices (Thymus vulgaris, Murraya koenigii, Ocimum gratissimum and Piper guineense) in alloxan-induced diabetic rats. Int. J. Biosci.. 2014;4(2):179-187.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phytol/Phytanic acid and insulin resistance: potential role of phytanic acid proven by docking simulation and modulation of biochemical alterations. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e45638

- [Google Scholar]

- Hyperglycaemia Lowering Effect of Kaurane Diterpenoids from the Fruits of Xylopia aethiopica (A. Dunal) Rich. Inter J. Med. Plants and Nat Prod.. 2018;4(3):11-19.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hypoglycaemic effects of Parkia biglobosa (Jacq) Benth seed extract in glucose-loaded and NIDDM rats. Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci.. 2009;3(3)

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of some anti-diabetic plants on the hepatic marker enzymes of diabetic rats. Afr. J. Biotechnol.. 2014;13(7):905-909.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antidiabetic potential of monoterpenes: A case of small molecules punching above their weight. Int. J. Mol. Sci.. 2018;19(1):4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Peperomia pellucida in diets modulates hyperglyceamia, oxidative stress and dyslipidemia in diabetic rats. J. Acute Dis.. 2012;1(2):135-140.

- [Google Scholar]

- Laboratory evaluation of ethanolic extracts of Citrus sinensis peels and Piper guineense (seeds and leaves) on mosquito larvae. J. Environ. Human. 2014;1(1):19-24.

- [Google Scholar]

- Toxicological evaluation of grains of paradise (Aframomum melegueta)[Roscoe] K. Schum. J. Ethnopharmacol.. 2010;127(2):352-356.

- [Google Scholar]

- Vicenin 2 isolated from Artemisia capillaris exhibited potent anti-glycation properties. Food Chem. Toxicol.. 2014;69:55-62.

- [Google Scholar]

- Dietary red chilli (Capsicum frutescens L.) is insulinotropic rather than hypoglycemic in type 2 diabetes model of rats. Phytotherapy Res.. 2008;22(8):1025-1029.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of crude and ethanolic extracts of Capsicum frutescens var. minima fruit against some common bacterial pathogens. Int. J. Complement. Alt. Med.. 2019;12(3):105-108.

- [Google Scholar]

- Influence of Xylopia aethiopica fruits on some hematological and biochemical profile. Am. J. Med. Sci.. 2011;4:191-196.

- [Google Scholar]

- Juliani, H.R., Koroch, A.R., Giordano, L., Amekuse, L., Koffa, S., Asante-Dartey, J., Simon, J.E., 2013. Piper guineense (Piperaceae): Chemistry, Traditional Uses, and Functional Properties of West African Black Pepper. In African Natural Plant Products Volume II: Discoveries and Challenges in Chemistry, Health, and Nutrition (pp. 33-48). American Chemical Society.

- Recent progress for the utilization of Curcuma longa, Piper nigrum and Phoenix dactylifera seeds against type 2 diabetes. West Indian Med. J.. 2015;64(5):527.

- [Google Scholar]

- Novel Piperine Derivatives with Antidiabetic Effect as PPAR-γ Agonists. Chem. Biol. Drug Des.. 2016;88(3):354-362.

- [Google Scholar]

- Red Pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) seed extract decreased hepatic gluconeogenesis and increased muscle glucose uptake in vitro. J. Med. Food. 2018;21(7):665-671.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of Aframomum melegueta on carbon tetrachloride induced liver injury. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci.. 2013;3(9):98.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biochemical and histopathological changes in Wistar rats following chronic administration of Diherbal mixture of Zanthoxy lumleprieurii and Piper guineense. J. Nat. Sci. Res.. 2012;2012(2):22-28.

- [Google Scholar]

- Isolation, characterization of syringin, phenylpropanoid glycoside from Musa paradisiaca tepal extract and evaluation of its antidiabetic effect in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Biomed. Prev. Nutr.. 2014;4:105-111.

- [Google Scholar]

- S. Kumar R., Singh, R., Kumar Dubey, A., Important aspects of post-prandial antidiabetic drug, acarbose Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 16 2016 2625 2633.

- Screening of antidiabetic and antihyperlipidemic potential of oil from Piper longum and piperine with their possible mechanism. Expert Opin. Pharmacother.. 2013;14:1723-1736.

- [Google Scholar]

- Insulinotropic and antidiabetic effects of β-caryophyllene with l-arginine in type 2 diabetic rats. J. Food Biochem.. 2020;44:e13156

- [Google Scholar]

- Chemical composition and antibacterial activity of essential oil from the leaves of Aframomum melegueta (Roscoe) K. Schum from Nigeria. J. Essent. Oil-Bear. Plants. 2015;18:222-229.

- [Google Scholar]

- Gingerols of Zingiber officinale enhance glucose uptake by increasing cell surface GLUT4 in cultured L6 myotubes. Planta Med.. 2012;78:1549-1555.

- [Google Scholar]

- Edible medicinal and non-medicinal plants. 2012;1:285-292.

- Total phenolics, capsaicinoids, antioxidant activity, and α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of three varieties of pepper seeds. Int. J. Food Prop.. 2020;23:1016-1035.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hypoglycemic and hypocholesterolemia effects of intragastric administration of dried red chili pepper (Capsicum annum) in alloxan-induced diabetic male albino rats fed with high-fat-diet. J. Food Nutr. Res.. 2014;2:850-856.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of NaCl and lime water on the hypoglycemic and antioxidant activities of Ocimum gratissimum in alloxan-induced diabetic rats. IOSR J. Pharm. & Biol. Sci.. 2013;8:1-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Investigation of Bioactive Compounds of Capsicum frutescence and Annona muricata by chromatographic techniques. J. Drug Deliv. Ther.. 2019;9:485-495.

- [Google Scholar]

- An ethnobotanical survey and antifungal activity of Piper guineense used for the treatment of fungal infections in West-African traditional medicine. J. Ethnopharmacol.. 2019;229:157-166.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antioxidant potential of Xylopia aethiopica fruit acetone fraction in a type 2 diabetes model of rats. Biomed. Pharmacother.. 2017;96:30-36.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antidiabetic potential of some less commonly used plants in traditional medicinal systems of India and Nigeria. J. Intercult. Ethnopharmacol.. 2015;4:78.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of aqueous leaves extract of Ocimum gratissimum on blood glucose levels of streptozocin-induced diabetic wistar rats. Afr. J. Biotechnol.. 2007;6(18)

- [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed, A., Victoria Awolola, G., Ibrahim, M.A., Anthony Koorbanally, N., Islam, M.S., 2019. Oleanolic acid as a potential antidiabetic component of Xylopia aethiopica (Dunal) A. Rich. (Annonaceae) fruit: bioassay guided isolation and molecular docking studies. Nat. Prod. Res. 1-4.

- Hypoglyceamic effects of aqueous extract of Aframomum melegueta leaf on alloxan-induced diabetic male albino rats. Pac. J. Med. Sci.. 2011;8:28-36.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anti-hyperglycemic and anti-hyperlipidemic potentials of methanol leaf extracts of Aframomum melegueta and Piper guineense. Eur. J. Med. Chem. Plants 2019:1-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antidiabetic activity of linalool and limonene in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat: a combinatorial therapy approach. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci.. 2014;6(8):159-163.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antidiabetic effect of d-limonene, a monoterpene in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Biomed. Prev. Nutr.. 2012;2:269-275.

- [Google Scholar]

- α-Glucosidase, α-amylase, and tyrosinase inhibitory potential of capsaicin and dihydrocapsaicin. J. Food Biochem.. 2020;44:e13099

- [Google Scholar]

- 6-shogaol inhibits advanced glycation end-products-induced IL-6 and ICAM-1 expression by regulating oxidative responses in human gingival fibroblasts. Molecules. 2019;24:3705.

- [Google Scholar]

- A comparative study of the phytochemical constituents, proximate and mineral compositions of Zingiber officinale, Curcuma longa, Aframomum sceptrum and Monodora myristica. Niger. Agric. J.. 2018;49(2):22-25.

- [Google Scholar]

- Possible antidiabetic and antihyperlipidaemic effect of fermented Parkia biglobosa (jacq) extract in alloxan-induced diabetic rats. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol.. 2006;33:808-812.

- [Google Scholar]

- Morphological study of the effects of aqueous leaf extract of Xylopia aethiopica on the pancreas in diabetic rats. J. Anat. Embryol. 2016:77-87.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial activity of Xylopia aethiopica, Aframomum melegueta and Piper guineense ethanolic extracts and the potential of using Xylopia aethiopica to preserve fresh orange juice. Afr. J. Biotechnol.. 2013;12

- [Google Scholar]

- Chemistry and biological evaluation of Nigerian plants with anti-diabetic properties. ACS Symp. Ser.. 2009;1021:186-207.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of acute and subacute toxicity of Alstonia congensis Engler (Apocynaceae) bark and Xylopia aethiopica (Dunal) A. Rich (Annonaceae) fruits mixtures used in the treatment of diabetes. Afr. J. Biotechnol.. 2008;7(6)

- [Google Scholar]

- Anti-diabetic effect of crude leaf extracts of Ocimum gratissimum in neonatal streptozotocin-induced type-2 model diabetic rats. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci.. 2012;4:77-83.

- [Google Scholar]

- Protective effects of Parkia biglobosa protein isolate on streptozotocin-induced hepatic damage and oxidative stress in diabetic male rats. Molecules. 2017;22:1654.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anti-diabetic potential of Ocimum gratissimum leaf fractions in fortified diet-fed streptozotocin treated rat model of type-2 diabetes. Medicines. 2017;4:73.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bioactive constituents, radical scavenging, and antibacterial properties of the leaves and stem essential oils from Peperomia pellucida (L.) Kunth. Pharmacogn. Mag.. 2017;13:S392.

- [Google Scholar]

- In vitro study on α-amylase inhibitory activities of Digitari aexilis, Pentadiplandra brazzeana (Baill) and Monodoramyristica. Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci.. 2014;8:2306-2313.

- [Google Scholar]

- Rehydration characteristics of dehydrated West African pepper (Piper guineense) leaves. Food Sci. Nutr.. 2014;2:664-668.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comprative effects of some medicinal plants: Anacardium occidentale, Eucalyptus globulus, Psidium guajava, and Xylopia aethiopica extracts in alloxan-induced diabetic male Wistar albino rats. Int: Biochem. Res; 2014. p. :2014.

- Onoja, S.O., Omeh, Y.N., Ezeja, M.I., Chukwu, M.N., 2014. Evaluation of the in vitro and in vivo antioxidant potentials of Aframomum meleguetam ethanolic seed extract. J. Trop. Med. 2014.

- Orwa, C., Mutua, A., Kindt, R., Jamnadass, R., Anthony, S., 2009. Agro forest tree Database: a tree reference and selection guide version 4.0. World Agroforestry Centre 15.

- Aframomum melegueta (Grains of Paradise) Ann. Microbiol. Infectious Dis.. 2020;2020(3):1-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Owolabi, M.S., Lawal, O.A., Ogunwande, I.A., Hauser, R.M., Setzer, W.N., 2013. Aroma chemical composition of Piper guineense Schumach. & Thonn. From Lagos, Nigeria: A new chemotype. Am. J. Essent. Oils Nat. Prod. 2013, 1, 37-40.

- Modulatory effect of methanol extract of Piper guineense in CCl4-induced hepatotoxicity in male rats. Int. J. Environ. Res.. 2017;14:955.

- [Google Scholar]

- Papitha, R., Renu, K., Selvaraj, I., Abilash, V.G., 2018. Anti-diabetic effect of fruits on different animal model system. In Bioorganic Phase in Natural Food: An Overview, 157-185.

- Evaluation of the anti-diabetic activity of some common herbs and spices: Providing new insights with inverse virtual screening. Molecules. 2019;24:4030.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hypoglycemic, anti-inflammatory and analgesic activity of Peperomea pellucida (L.) Hbk (Piperaceae) Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res.. 2013;4:458.

- [Google Scholar]

- Potential dual role of eugenol in inhibiting advanced glycation end products in diabetes: proteomic and mechanistic insights. Sci. Rep.. 2016;6:1-13.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mechanisms for antidiabetic effect of gingerol in cultured cells and obese diabetic model mice. Cytotechnology. 2015;67:641-652.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ameliorating effect of eugenol on hyperglycemia by attenuating the key enzymes of glucose metabolism in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Mol. Cell. Biochem.. 2014;385:159-168.

- [Google Scholar]

- Preliminary study of hypoglycemic effect of locust bean (Parkia biglobosa) on Wistar albino rat. J. Sci. Res. Rep. 2015:467-472.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antidiabetic and antihyperlipidemic activities of different fractions of extract of Peperomia pellucida (L.) in alloxan induced diabetic mice. J. Sci. Technol.. 2016;6:73-79.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phytochemical analysis, in vitro antioxidant activity and inhibition of key diabetic enzymes by selected Nigerian medicinal plants with antidiabetic potential. Indian J. Pharm. Educ. Res.. 2019;53:250-260.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial activities of African medicinal spices and vegetables. Academic Press; 2017.

- Essential oil of Xylopia aethiopica from Cameroon: Chemical composition, antiradical and in vitro antifungal activity against some mycotoxigenic fungi. J. King Saud Univ. Sci.. 2018;30:466-471.

- [Google Scholar]

- Exploiting the potential of indigenous agroforestry trees: Parkia biglobosa and Vitellaria paradoxa in sub-Saharan Africa. New Vistas Agroforestry 2004:207-220.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chicoric acid, a new compound able to enhance insulin release and glucose uptake. Biochem. Bioph. Res. Co. 2008;377:131-135.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bioactive constituents of the bark of Parkia biglobosa. Fitoterapia. 2000;71:118-125.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of extract of leaf and seed of Piper guineense on some smooth muscle activity in rat, Guinea pig and Rabbit. Phytother. Res.. 1996;10:596-599.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of aqueous extract of Piper guineense seeds on some liver enzymes, antioxidant enzymes and some hematological parameters in albino rats. Intern J. plant Sci. Ecol.. 2015;1:167-171.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of nutritive potential and anti-oxidative properties of African nutmeg (Monodora myristica) Niger. Agric. J.. 2012;43

- [Google Scholar]

- Synergic effects of some medicinal plants on anti-oxidant status and lipid peroxidation in diabetic rats. Afr. J. Pharm. Pharmacol.. 2013;7:3011-3018.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antidiabetic effect of oleanolic acid: A promising use of a traditional pharmacological agent. Phytother. Res.. 2011;25:1031-1040.

- [Google Scholar]

- The α-glucosidase and α-amylase inhibitory activity from different chili pepper extracts. Int. Food Res. J.. 2016;23(4)

- [Google Scholar]

- Secondary metabolites screening and acute toxicity test of Peperomia pellucida (L.) Kunthm ethanolic extracts. Int. J. Pharmtech Res.. 2017;10:31-38.

- [Google Scholar]

- 6-paradol and 6-shogaol, the pungent compounds of ginger, promote glucose utilization in adipocytes and myotubes, and 6-paradol reduces blood glucose in high-fat diet-fed mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci.. 2017;18:168.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antihypergylceamic activity of Piper guineense in diabetic female albino wistar rats. Int. J. Pharm. Phytopharmacol. Res.. 2017;7:1-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Xylopia aethiopica seeds from two countries in West Africa exhibit differences in their proteomes, mineral content and bioactive phytochemical composition. Molecules. 2019;24:1979.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and evaluation of novel oleanolic acid derivatives as potential antidiabetic agents. Chem. Biol. Drug Des.. 2014;83:297-305.

- [Google Scholar]