Translate this page into:

Solid state fermentation of amylase production from Bacillus subtilis D19 using agro-residues

⁎Corresponding author. sshine@ksu.edu.sa (Shine Kadaikunnan)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

The selected bacterial strain, Bacillus subtilis D19 was inoculated into the solid residues such as, wheat bran, banana peel, orange peel, rice bran and pine apple peel. Among the tested solid wastes, wheat bran showed enhanced the production of amylase (640 U/g) than other tested substrates. The carbon and nitrogen sources were initially screened by traditional method using wheat bran medium. Amylase activity was high in the wheat bran substrate supplemented with starch (670 U/g). The tested nitrogen sources enhanced amylase activity. Among the selected nitrogen sources, yeast extract stimulated maximum production of amylase (594 U/g). In two level full factorial experimental design, maximum activity (1239 U/g) was obtained at pH 9.0, 70% (v/w) moisture, 1% (w/w) starch, 1% (w/w) yeast extract and 5% (v/w) inoculums. Central composite design and response surface methodology was used to optimize the required medium concentration (pH, moisture content of the medium and starch concentrations) for the maximum production of amylase. All three selected variables enhanced amylase production over 3 fold in optimized medium.

Keywords

Bacillus subtilis

Solid state fermentation

Amylase production

Agro-residues

1 Introduction

Amylases are the glucosidal linkage of complex polysaccharides (Pandey et al., 2000). These enzymes plays very important role in various industrial processes. The fungi such as, Penicillium sp., Rhizopus sp., Cephalosporium sp. and Aspergillus niger are the important producer of α-amylase (Suganthi et al., 2011; Valsalam et al., 2019; Arokiyaraj et al., 2015). Moreover, the synthetic media is highly expensive and almost not suitable for commercial production of industrial enzymes. Traditional optimization method is time consuming and it frequently ignores the interactions between factors. However, statistical optimization method has various advantages than traditional optimization method. Statistical optimization method such as, Placket and Burman design has been frequently employed to screen large number of factors. Response surface methodology (RSM) including, fractional factorial design, full factorial design, regression analysis were useful to find the significant factors and helps to build models to evaluate the interaction between medium components and to select suitable conditions of factors for a optimum response (Reddy et al., 2008). RSM has been used for optimizing process parameters to enhance the production of enzymes for various applications (Saran et al., 2007; Mohandas et al., 2010). In statistical method optimization strategy, contour plots and 3D response surface plots can provide clear analysis of interactions between factors. Hence, optimization of enzyme production by statistical approach is frequently employed for predicting optimum response and to enhance enzymes production (Mullai et al., 2010). In this study, B. subtilis D19 was used for the production of amylase in Solid state fermentation for various industrial processes.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Bacterial strain

Food sample was used for the isolation of bacteria for the production of amylase in SSF.

2.2 Characterization of amylase producing bacterial isolate

16S rDNA was sequenced using universal forward and reverse primers (Arasu et al., 2013). The 16S rDNA gene sequence was analyzed and sequence similarity was assessed and sequences were submitted to GenBank database.

2.3 Solid state fermentation

In our study, various agricultural wastes were collected locally. The agricultural residues such as, wheat bran, banana peel, orange peel, rice bran and pine apple peel, were screened initially. These agricultural by-products was not readily available as dried form, hence, the collected substrates were incubated for 12 h at 80 °C to eliminate moisture content of the solid substrates. The agro-residue was weighed (5.0 g) and desired moisture level was maintained (75%, v/w) and sterilized. It was rotated several times in order to mix the inoculums with substrate.

2.4 Amylase extraction and enzyme assay

Enzyme assay was performed as described by Miller (1959). Soluble starch (1%, w/v) was used as the substrate. Sample (0.1 ml) was incubated with 1 ml substrate for 30 min. Then one ml DNS reagent was added and boiled for 10 min. Finally the optical density of the sample was read at 540 nm using a UV–visible spectrophotometer.

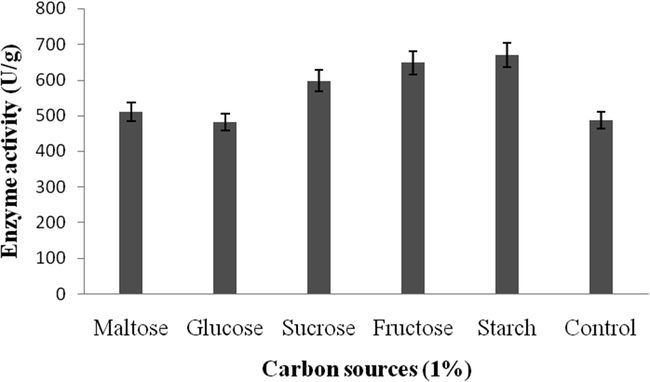

2.5 Screening of carbon and nitrogen source on amylase production

In this study, production of amylase by B. subtilis was optimized by traditional method in SSF. The nutrient factors (carbon and nitrogen source) were selected and screened by this method. These nutrient sources were supplemented with 5 g wheat bran and amylase assay was carried out.

2.6 Bacillus subtilis D19 enzyme optimization

Two factors were selected at two different levels. Inoculum level positively influences on enzymes production. Yeast extract (nitrogen source) and starch (carbon source) were selected based on initial screening experiments. The 25 factorial experimental designs consisted of a total of 32 runs. Experiment was performed in 100 ml Erlenmeyer flasks containing 5.0 g substrate (wheat bran) with suitable media components.

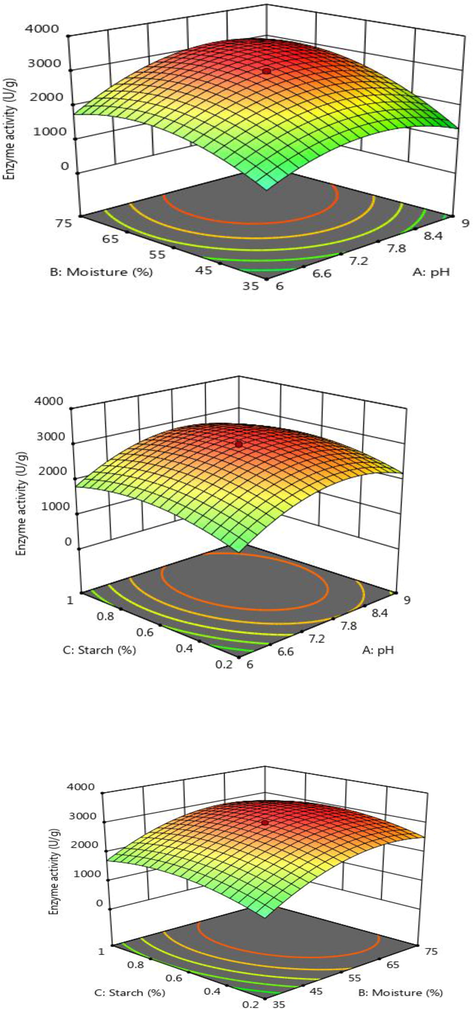

Experiment was conducted in duplicate and an average was considered as amylase activity (response Y). From the analyzed results, three factors were selected to optimize the concentration of variables by central composite design and response surface methodology (p < 0.05). The selected variables were, pH, moisture and starch. These variables used were tested at five different levels (−α, −1, 0, +1, +α). Central composite design consists of 20 experimental runs for three selected variables. Finally, the second-order polynomial equation was used to fit the experimental results. For a three-factor system, the second order polynomial equation is as follows (2): where Y is the response; b0 is the offset term; and bi, bii, and bij are the coefficients of linear terms, square terms, and coefficients of interactive terms, respectively. Xis are A, B, and C; Xijs are AB, AC, and BC (A = pH; B = moisture; C = starch). Amylase analysis was performed in duplicates and the mean value was taken as response Y.

3 Results

3.1 Screening and characterization of amylase producing B. subtilis D19

The bacterium B. subtilis D19 showed considerable activity on starch agar plates. This organism produced more than 20 mm zone on the substrate agar plate, which showed more hydrolytic zone than the other tested bacterial strains. The selected bacterial isolate was this organism hydrolyzed starch, casein and negative for gelatine hydrolysis. It was identified based on these biochemical characters and 16S rDNA sequencing. The 16S rDNA sequence (KF 638634.1) showed more than 99% similarity with Bacillus subtilis D19.

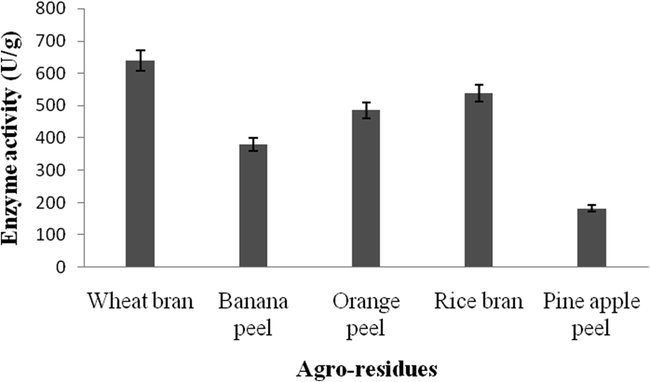

3.2 Effect of solid substrates

In this study, the selected bacterial strain, B. subtilis was inoculated into the solid residues such as, wheat bran, banana peel, orange peel, rice bran and pine apple peel. Among the tested solid wastes, wheat bran enhanced the production of amylase (640 U/g) than other tested substrates. Also, the other substrates such as, rice bran and orange peel, banana peel and pine apple peel supported amylase production (Fig. 1).

Effect of agro-residues on amylase enzyme production by B. subtilis.

3.3 Optimization

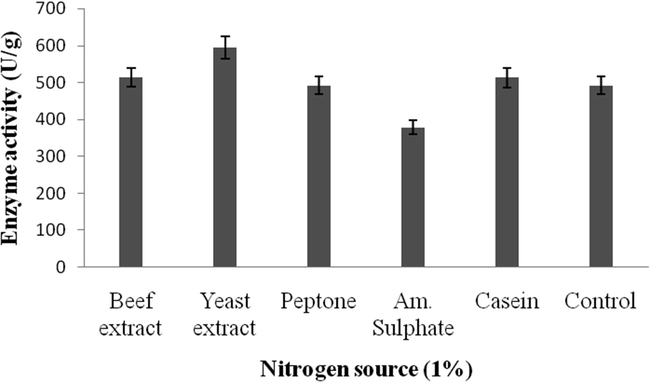

Amylase activity was high in the wheat bran supplemented with starch (670 U/g) (Fig. 2a). The tested nitrogen sources enhanced amylase activity (594U/g) (Fig. 2b).

a. Effect of carbon on amylase enzyme production by B. subtilis.

b. Effect of nitrogen on amylase enzyme production by B. subtilis.

3.4 Screening and optimization of variables by statistical approach

In B. subtilis D19, amylase production was screened by a two-level full factorial design and the concentration was optimized by central composite design. In two level full factorial design enzyme yield ranged between 145 and 1239 U/g (Table 1). In this experimental design, maximum activity (1239 U/g) was obtained at pH 9.0, 70% moisture, 1% starch, 1% yeast extract and 5% inoculums. ANOVA of the experimental data was evaluated and the regression model was statistically significant and described in Table 2. In our study, the “F” value of the CCD model was 9.30 and this model is statistically significant. The p-value of this model is 0.0052. In this model case A, B, CE, DE, ABD, ACD, ACE, ABCD, ABDE, BCDE, ABCDE are significant model terms (Tables 3 and 4). The interactive effect between pH, moisture content and starch for amylase production by B. subtilis D19 were described in Fig. 3(a–c). In our study, amylase increased higher starch concentrations up to optimum level and decreased.

Run

A:pH

B:Moisture

C:Starch

D:Yeast extract

E:Inoculum

Enzyme activity

%

%

%

U/g

1

9

70

0.1

0.1

5

325

2

9

70

1

1

1

540

3

6

40

0.1

1

1

299

4

9

40

1

1

1

605

5

6

40

1

1

1

340

6

6

40

0.1

1

5

755

7

9

70

0.1

1

1

721

8

9

40

0.1

1

1

729

9

6

40

1

1

5

425

10

6

70

0.1

1

5

440

11

6

70

0.1

0.1

1

540

12

9

40

0.1

1

5

145

13

9

70

0.1

0.1

1

672

14

9

40

1

0.1

1

376

15

9

40

1

0.1

5

941

16

9

70

1

0.1

1

546

17

9

40

0.1

0.1

1

1163

18

9

40

1

1

5

912

19

6

40

1

0.1

5

471

20

6

70

1

1

5

514

21

9

70

0.1

1

5

935

22

6

40

0.1

0.1

5

181

23

6

70

0.1

1

1

481

24

6

40

0.1

0.1

1

321

25

6

70

1

1

1

270

26

9

70

1

0.1

5

676

27

9

70

1

1

5

1239

28

6

70

1

0.1

1

826

29

6

70

1

0.1

5

550

30

9

40

0.1

0.1

5

710

31

6

70

0.1

0.1

5

890

32

6

40

1

0.1

1

381

Source

Sum of squares

df

Mean square

F-value

p-value

Model

2.213E+06

25

88537.11

9.30

0.0052

A-pH

3.941E+05

1

3.941E+05

41.38

0.0007

B-Moisture

62216.28

1

62216.28

6.53

0.0431

C-Starch

56907.03

1

56907.03

5.92

0.0506

AB

50007.03

1

50007.03

5.25

0.0618

AC

9975.78

1

9975.78

1.05

0.3456

AD

34650.28

1

34650.28

3.64

0.1051

BD

6300.03

1

6300.03

0.6615

0.4471

BE

13081.53

1

13081.53

1.37

0.2856

CD

4394.53

1

4394.53

0.4614

0.5223

CE

1.784E+05

1

1.784E+05

18.73

0.0049

DE

66703.78

1

66703.78

7.00

0.0382

ABC

8224.03

1

8224.03

0.8635

0.3886

ABD

4.007E+05

1

4.007E+05

42.08

0.0006

ABE

36113.28

1

36113.28

3.79

0.0994

ACD

1.034E+05

1

1.034E+05

10.86

0.0165

ACE

3.513E+05

1

3.513E+05

36.89

0.0009

BCD

17344.53

1

17344.53

1.82

0.2259

BCE

41112.78

1

41112.78

4.32

0.0830

BDE

34914.03

1

34914.03

3.67

0.1040

ABCD

1.078E+05

1

1.078E+05

11.32

0.0152

ABCE

17437.78

1

17437.78

1.83

0.2248

ABDE

1.226E+05

1

1.226E+05

12.88

0.0115

ACDE

5751.28

1

5751.28

0.6039

0.4666

BCDE

84769.03

1

84769.03

8.90

0.0245

ABCDE

59254.03

1

59254.03

6.22

0.0469

Residual

57141.69

6

9523.61

Cor Total

2.271E+06

31

Std

A:pH

B:Moisture

C:Starch

Enzyme activity

%

%

U/g

7

6

75

1

1520

15

7.5

55

0.6

2980

14

7.5

55

1.27272

2500

2

9

35

0.2

435

3

6

75

0.2

1098

5

6

35

1

1240

11

7.5

21.3641

0.6

110

17

7.5

55

0.6

2970

1

6

35

0.2

1012

6

9

35

1

1019

18

7.5

55

0.6

3019

19

7.5

55

0.6

2890

16

7.5

55

0.6

3010

9

4.97731

55

0.6

92

13

7.5

55

−0.0727171

1900

4

9

75

0.2

1892

12

7.5

88.6359

0.6

3092

10

10.0227

55

0.6

2742

8

9

75

1

1780

20

7.5

55

0.6

2982

Source

Sum of squares

df

Mean square

F-value

p-value

Model

1.724E+07

9

1.916E+06

5.31

0.0077

A-pH

1.626E+06

1

1.626E+06

4.51

0.0598

B-Moisture

4.228E+06

1

4.228E+06

11.71

0.0065

C-Starch

3.325E+05

1

3.325E+05

0.9213

0.3598

AB

4.287E+05

1

4.287E+05

1.19

0.3013

AC

3960.50

1

3960.50

0.0110

0.9186

BC

31500.50

1

31500.50

0.0873

0.7737

A2

5.874E+06

1

5.874E+06

16.27

0.0024

B2

4.738E+06

1

4.738E+06

13.13

0.0047

C2

1.884E+06

1

1.884E+06

5.22

0.0454

Residual

3.610E+06

10

3.610E+05

Lack of Fit

3.599E+06

5

7.198E+05

343.27

<0.0001

Pure Error

10484.83

5

2096.97

Cor Total

2.085E+07

19

Response surface plot for amylase production by B. subtilis.

4 Discussion

Carbon sources in the culture medium stimulated amylase production and has been described previously. In Bacillus cereus, supplemented carbon sources positively regulated amylase production (Tamamura et al., 2014; Arasu et al., 2019; Babu and Satyanarayana, 1993). In Bacillus thermooleovorans, amylase activity was enhanced by starch, lactose, glucose and maltose (Narang and Satyanarayana, 2001; Arasu et al., 2017).

In our study, amylase production was enhanced by the supplementation of yeast extract as nitrogen source (594 U/g). However, these required nutrient sources may differ from species to species. In Bacillus sp. amylase production was enhanced by the addition of ammonium nitrate with the culture medium (Hashemi et al., 2010). After initial screening, the fermentation bioprocess was further optimized by statistical approach. The variables were screened by a two level full factorial design and further optimized by central composite design. RSM has been employed previously to optimize the variables (Rahman et al., 2004). Low cost medium and culture medium optimization is very important (Chauhan and Gupta, 2004; Dash et al., 2015; Rajagopalan and Krishnan, 2008). Hence, optimization of any new bacterial isolate is pre request for any industrial processing. In our study, this organism preferred alkaline pH, and starch is preferable for the synthesis of amylase. The influence of nutritional and physical factors was reported by Sahnoun et al. (2015). In a study, Tanyildizi et al. (2007) reported that pH 7.0 is optimum for the production of amylase from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens. Most of the bacteria from the genus Bacillus use pH between 7.0 and 10.0 for the production of amylase (Saxena et al., 2007; Goyal et al., 2005). The designed CCD model in this study is statistically significant for B. subtilis. RSM has been used for the production of enzymes and coefficient estimate was analyzed (Olivera et al., 2004; Adinarayana and Ellaiah, 2002). The pH of the substrate (wheat bran) also positively influenced on amylase production in B. subtilis D19. The influence of pH on enzyme production has been reported earlier by Pandey et al. (2000). In enzyme bioprocess, physical parameters influenced on amylase production (Tamilarasan et al., 2010; Agrawal et al., 2005; Ikram-ul-Haq et al., 2003; Vijayaraghavan and Vincent, 2012). In this study amylase activity was 3 fold in optimized medium than unoptimized culture medium. Generally, RSM mediated optimization procedures enhanced enzyme production. In a study, Bacillus sp. RKY3 was used to optimize enzyme production and achieved 2.3 fold enzyme activities (Anbu et al., 2008)

5 Conclusions

In conclusion, production of amylase at optimum pH and moisture content and supplementation of starch in the wheat bran media seemed to enhance the enzyme yield. This study revealed the influence of physical factors and carbon source on amylase production.

Acknowledgement

The authors extend their appreciation to the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSP-2019/70), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Response surface optimization of the critical medium components for the production of alkaline protease by a newly isolated Bacillus sp. J. Pharm. Pharmaceut. Sci.. 2002;5:272-278.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hydrolysis of starch by amylase from Bacillus sp. KCA102: a statistical approach. Process Biochem.. 2005;40:2499-2507.

- [Google Scholar]

- Extracellular keratinase from Trichophyton sp. HA-2 isolated from feather dumping soil. Inter. J. Biodeter. Biodegrad.. 2008;62(3):287-292.

- [Google Scholar]

- Green chemical approach towards the synthesis of CeO2 doped with seashell and its bacterial applications intermediated with fruit extracts. J. Photochem. Photobiol., B: Biol.. 2017;172:50-60.

- [Google Scholar]

- One step green synthesis of larvicidal, and azo dye degrading antibacterial nanoparticles by response surface methodology. J. Photochem. Photobiol., B: Biol.. 2019;190:154-162.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antibacterial and antifungal activities of polyketide metabolite from marine Streptomyces sp. AP-123 and its cytotoxic effect. Chemosphere. 2013;90(2):479-487.

- [Google Scholar]

- Green synthesis of Silver nanoparticles using aqueous extract of Taraxacum officinale and its antimicrobial activity. South Indian J. Biol. Sci.. 2015;2:115-118.

- [Google Scholar]

- Parametric optimizations for extracellular alpha-amy- lase production by thermophilic Bacillus coagulans B49. Folia. Microbiol.. 1993;38:77-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- Application of statistical experimental design for optimization of alkaline protease production from Bacillus sp. RGR-14. Process Biochem.. 2004;39(1):2115-2122.

- [Google Scholar]

- Molecular identification of a newly isolated Bacillus subtilis BI19 and optimization of production conditions for enhanced production of extracellular amylase. BioMed. Res. Int.. 2015;1–9

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A novel raw starch digesting thermostable a-amylase from Bacillus sp. I-3 and its use in the direct hydrolysis of raw potato starch. Enzyme Microb. Technol.. 2005;37:723-734.

- [Google Scholar]

- Development of a solid-state fermentation process for production of an alpha amylase with potentially interesting properties. J. Biosci. Bioeng.. 2010;110:333-337.

- [Google Scholar]

- Production of alpha amylase by Bacillus licheniformis using an economical medium. Bioresour. Technol.. 2003;87:57-61.

- [Google Scholar]

- Use of dinitrosalicylic acid reagent for determination of reducing sugars. Anal. Chem.. 1959;31:426-428.

- [Google Scholar]

- Statistical optimization and neural modelling of amylase production from banana peel using Bacillus subtilis MTCC 441. Int. J. Food Eng.. 2010;6:1-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Statistical analysis of main and Interaction effects to optimize xylanase production under submerged cultivation conditions. J. Agric. Sci.. 2010;2(1):144-153.

- [Google Scholar]

- Thermostable α-amylase production by an extreme thermophilic Bacillus thermooleovorans. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2001;32:1-35.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bacteriocin production by Bacillus licheniformis strain P40 in cheese whey using response surface methodology. Biochem. Eng. J.. 2004;21:53-58.

- [Google Scholar]

- Optimization of growth medium for the production of cyclodextrin glucanotransferease from Bacillus stearothermophilus HR1 using response surface methodology. Process Biochem.. 2004;39:2053-2060.

- [Google Scholar]

- Alpha amylase production from catabolic depressed Bacillus subtilis KCC103 utilizing sugarcane bagasse hydrolysate. Bioresour. Technol.. 2008;99:3044-3050.

- [Google Scholar]

- Optimization of alkaline protease by batch culture of Bacillus sp. RKY3 through Placket-Burman and response surface methodological approaches. Bioresour. Technol.. 2008;99:2242-2249.

- [Google Scholar]

- Aspergillus oryzae S2 alpha-amylase production under solid state fermentation: optimization of culture conditions. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.. 2015;75:73-78.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Statistical optimization of conditions for protease production from Bacillus sp. and its scale-up in a bioreactor. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol.. 2007;141:229-239.

- [Google Scholar]

- A highly thermostable and alkaline amylase from a Bacillus sp. Bioresour. Technol.. 2007;98:260-265.

- [Google Scholar]

- Amylase production by Aspergillus niger under solid state fermentation using agroindustrial wastes. IJEST. 2011;3(2):1756-1760.

- [Google Scholar]

- Enhancement of hydrolytic activity of thermophilic alkalophilic α-amylase from Bacillus sp. AAH-31 through optimization of amino acid residues surrounding the substrate binding site. Biochem. Eng. J.. 2014;86:8-15.

- [Google Scholar]

- Optimization of operating variables for corn flour starch hydrolysis using immobilized α-amylase by response surface methodology. Int. J. Biotechnol. Biochem.. 2010;6:841-850.

- [Google Scholar]

- Production of bacterial α-amylase by B. amyloliquefaciens under solid substrate fermentation. Biochem. Eng. J.. 2007;37:294-297.

- [Google Scholar]

- Rapid biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from the leaf extract of Tropaeolum majus L. and its enhanced in-vitro antibacterial, antifungal, antioxidant and anticancer properties. J. Photochem. Photobiol., B: Biol.. 2019;191:65-74.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cow dung a novel, inexpensive substrate for the production of a halo-tolerant alkaline protease by Halomonas sp. PV1 or eco-riendly applications. Biochem. Eng. J.. 2012;69:57-60.

- [Google Scholar]