Translate this page into:

Smart applications of bionanosensors for BCR/ABL fusion gene detection in leukemia

⁎Corresponding author at: Departamento de Bioquímica, UFPE, 50670-901 Recife, PE, Brazil. csrandrade@gmail.com (César A.S. Andrade)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

The present review discuss the relevance and innovative state-of-the-art on molecular diagnosis of leukemia. This morbidity is one of the most common types of cancer with an annual incidence of 250,000 new cases. The prevalence of leukemia among children up to 15 years of age is 30% on all cases of cancer reported in the childhood. The BCR/ABL fusion gene is one of the most important biomarkers in leukemia, being found in all cases of chronic myeloid leukemia and up to 40% of cases of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Genosensors are considered smart devices for identification of BCR/ABL fusion gene in clinical samples. Molecular techniques can contribute to early diagnosis of cancer, monitoring of minimal residual disease and implementation of effective drug therapies. The present review presents the scientific advances in the last decades on DNA biosensors constructed for BCR/ABL fusion gene detection. The assembly of nanostructured platforms, molecular immobilization strategies and analytical performances of the biodevices are discussed. The present review assesses the potential of electrochemical and optical techniques for BCR/ABL fusion gene detection. Electrochemical genosensors based on engineered nanomaterials at the transduction interface are useful to obtain high levels of sensitivity (up to 10−18 M). On the other hand, optical genosensors had higher detection limits (10−15 M). The analytical response time and reusability of genosensors for BCR/ABL fusion gene identification in small sample volumes (in the order of μL) were discussed. The present review highlighted nanostructured platforms as promising tool for diagnosis and monitoring of BCR/ABL fusion gene in leukemia patients.

Keywords

BCR/ABL fusion gene

Biosensor

DNA

Leukemia

Nanotechnology

1 Background

Leukemia is one of the most common cancer worldwide, presenting 250,000 cases annually (Ferlay et al., 2012). Leukemia is described as a malignant disease caused by abnormal white blood cells produced in bone marrow. An exacerbated and uncontrolled production of abnormal blood cells occur, leading to a decreased production of healthy blood cells, promoting the rise of bleeding, several infections and severe anemia (Inamdar and Bueso-Ramos, 2007). In addition, leukemic cells can also spread to other organs such as spleen, brain, lymph nodes and other tissues (Inamdar and Bueso-Ramos, 2007).

The clinical practice and scientific research are a support to define the specific hematologic disease (Vardiman, 2010). World Health Organization (WHO) elaborates a differentiated hematopoietic and lymphoid tumors classification based on morphological, clinical, immunophenotypic and genotypic parameters. WHO classified hematopoietic neoplasms according to the lineage of the neoplastic cells as myeloid, lymphoid, histiocytic/dendritic, neutrophilic, eosinophilic, mastocytic, basophilic, monoblastic, monocytic or ambiguous. In addition, leukemias are subclassified according to their clinical evolution in acute or chronic (Arber et al., 2016).

Genetic abnormalities are characteristic of human malignancies (Guarnerio et al., 2016) and characterized by variations of the number of DNA copies and aberrations in the chromosome structure resulting from mutations or gene fusions (Bochtler et al., 2015). Gene fusion is a DNA recombination that involves the exchange of genetic material between chromosomes or between distinct regions of the same chromosome (van Gent et al., 2001). The molecular mechanisms responsible for obtaining a hybrid gene are translocation (t), deletion, insertion and chromosomal inversion (Feuk et al., 2006). Oncogenic fusion occurs in neoplastic cells and includes at least one proto-oncogene during DNA recombination process. Proteins derived from oncogenic fusion have abnormal activities and contribute to the development of cancer, such as leukemia (Mitelman et al., 2007; Nero et al., 2014).

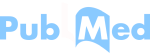

BCR/ABL translocation can be observed in myeloproliferative neoplasms, acute leukemia of ambiguous lineage and precursor lymphoid neoplasms class as chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML) (Vardiman, 2010). Philadelphia chromosome (Ph chromosome) is a shortened chromosome 22, resulting from translocation between long arms of chromosome 9 and 22 in hematopoietic stem cells, presented as t(9;22)(q34;q11). In addition, Ph chromosome is found in over 90% of patients with CML (Rowley, 1973). Molecular consequences are formation of BCR/ABL fusion gene on chromosome 22 and a reciprocal ABL-BCR on chromosome 9 (Chandra et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2014a,b). The resulting BCR/ABL protein is located in the cytoplasm with a deregulated tyrosine kinase activity (Ben-Neriah et al., 1986). Three main types of hybrid genes BCR/ABL are observed, producing three isoforms of tyrosine kinase protein with abnormal activity: p230BCR/ABL, p210BCR/ABL, p190BCR/ABL (Melo, 1996). p190BCR/ABL is an uncommon isoform in cases of CML and often observed in children with ALL. p210BCR/ABL is present in most patients with CML in stable phase and some cases of ALL and AML (Li and Du, 1998; Maurer et al., 1991; Winter et al., 1999) (Fig. 1).

Translocation (9;22) and BCR/ABL transcripts associated to CML, AML and ALL.

1.1 Conventional diagnostic methods

Chromosome banding techniques (CBT) triggered the development and improvement of several others techniques for molecular mechanisms studies. Detection of chromosomal abnormalities was helpful to assist diagnosis, prognosis and monitoring the effectiveness of treatment. The methods used for gene fusion identification are mainly molecular techniques. Fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) is a technique that allows the narrowing of breakpoint regions for hundreds of Kb. Additionally, real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and flow cytometry immunophenotyping can be used as new alternatives, offering good sensibility and specificity as compared to chromosomal banding (Bennour et al., 2012; Branford et al., 2004; Mertens et al., 2015). However, these are high-cost techniques and require specialized technicians (Craig and Foon, 2008; Weir and Borowitz, 2001). Both techniques exhibit obstacles such as difficulty in obtaining metaphase chromosome spreads for specific types of tumors and growth problems of some lineage cells in vitro (Arber et al., 2016). It is required the use of refined culture conditions, aiming to create a sufficient number of mitosis to obtain enough material (e.g. DNA, RNA, proteins) (Guarnerio et al., 2016). Complex karyotypes and chromosomal rearrangements are observed in neoplasia, increasing the difficulty to identifying them (Hajingabo et al., 2014; Mitelman et al., 2007). Thus, the development of innovative and effective alternatives for BCR/ABL gene fusion detection is of great interest for leukemia diagnosis.

1.2 Impact of nanotechnology for leukemia diagnosis

Nanotechnology has an important role for innovation and development of new technologies, since involves a multidisciplinary research field mainly associating engineering, biology, chemistry and physics. Nanotechnology related to the development of sensor devices results in 2200 patents between 2000 and 2010 (Antunes et al., 2012). World market nanotechnology products reached US$254 billion mark in 2009 (Roco et al., 2011). In 2015, a growth in financial operations about US$ 3 trillion related to nanotechnology was observed (Guarnerio et al., 2016).

Bionanotechnology is a field of the nanotechnology related to the development of biological devices to detect a large variety of microorganisms, viruses, enzymes and even identify chromosomal abnormalities such as BCR/ABL translocation. Biodevices are present in simple daily life, hospital and industrial areas (Henry, 1990). Along of the years, a growth in the number of studies dedicated to the development of biosensors has been observed (Bochtler et al., 2015). The global biosensors market was valued from about US$2 billion in 2000 to an expected value of US$17 billion in 2018 (Turner, 2013).

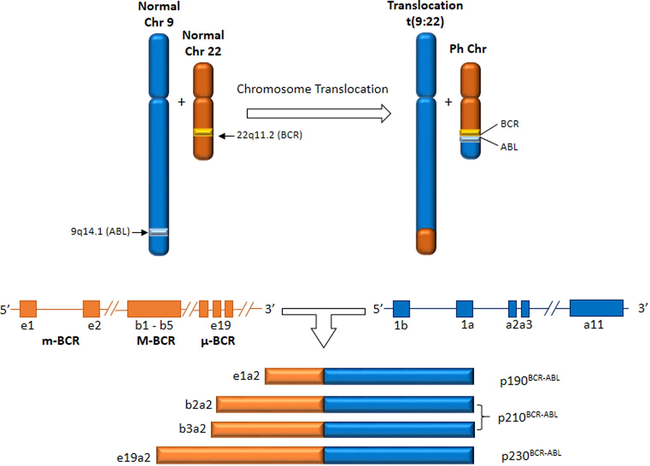

Biosensors are defined as electronic devices capable of providing quantitative or semi-quantitative analytical information on molecular targets (Scheller et al., 2001). These devices consist of three basic functional units: (a) element receptor; (b) transducer; and, (c) amplification and signal processing system (Grieshaber et al., 2008; Silva et al., 2014). A biomolecule can be used as receptor element responsible for recognition of the molecular target through specific intermolecular interactions or by catalytic reactions. The transducer is responsible for converting the biochemical response obtained from the biorecognition process in a measurable signal proportional to the concentration of the detected analyte (Fig. 2). In addition, the most common transducers are optical, electrochemical, calorimetric, piezoelectric, acoustic and magnetic (Perumal and Hashim, 2014). Finally, the electronic system promotes the amplification and processing of the analytical signal (Rocchitta et al., 2016).

Schematic representation of DNA biosensor developed to BCR/ABL fusion gene detection. Initially, oligonucleotide probe specifically recognize BCR/ABL fusion gene. The solid surface on which the probe was immobilized is responsible for transducing the biorecognition signal into a measurable signal proportional to oncogene concentration.

Biosensors are able to identify diverse analytes using antibodies (Liu et al., 2014a,b), antigens (Dong and Shannon, 2000), enzymes (Saei et al., 2013), proteins (Zhao et al., 2016), cells (Liu et al., 2014a,b), RNA (Campuzano et al., 2014) and DNA molecules (Hu et al., 2014; Malecka et al., 2016). DNA biosensors also known as genosensors have been extensively used due to the excellent selectivity and specificity. Genosensors are based on hybridization process through a specific complementary association between the oligonucleotide probe and DNA target. Nucleic acids exhibit electrochemical activity due to their structural components (Labuda et al., 2010). The basic element to obtain a genosensor is a single-stranded (ss) DNA (probe) with capability to recognize its complementary DNA (DNA target). If the target sequence matches perfectly with DNA probe a double-stranded (ds) DNA is obtained, ensuring recognition of the analyte (Palecek, 2009).

Genosensor technology offers a wide potential of applicability for clinical and laboratory diagnosis, allowing a direct real-time analysis of molecular targets with low cost compared to other available methods (Drummond et al., 2003). In addition, the synergy obtained between different nanomaterials is crucial for obtaining robust sensor systems with high sensitivity (Oliveira et al., 2014). Sensor systems exhibit multiple functions such as recognition/discrimination, appropriate analytical response, low detection limit and fast analysis. Therefore, genosensors can be considered smart biodevices for diagnosis of numerous human malignancies (Sadik et al., 2010; Tjong et al., 2014).

The use of DNA sequences as a recognition element for BCR/ABL fusion gene and nanostructured platforms for the development of smart genosensors will be discussed in the next section. In particular, emphasis will be given to electrochemical and optical signal transduction methods due to their extensive use for oncogenetic diagnosis.

2 Dna as sensing element for biosensors

The genome project (Palca, 1992; Weissenbach, 1998) allowed evaluate the genetic sequence of human genes. From this discovery, a highlighted development of accurate diagnostic tools based on hybridization procedures for detection of various genetic mutations has been observed. Mutations influence the development of epigenetic studies and development of new therapeutic tools (Kasprzak and Zabel, 2001).

DNA has been used as a biosensor element due to its greater structural stability at different temperatures. Its thermal stability contributed to the development of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (Dijkstra and de Jager, 1998) and real-time PCR (Jia, 2012). PCR technique is based on the use of primers, which can be used as specific DNA sequences for gene mutations detection (Mir et al., 2015). Primer is a short sequence of RNA or DNA (generally about 10 base pairs – bp) used as a starting point for DNA synthesis. A probe is a segment of DNA (18–50 bp) capable to adhere to its opposite DNA strand and can be chemically labeled.

Different strategies for CML diagnosis are based on detecting BCR/ABL fusion gene (Ph chromosome). The translocation process between chromosomes 9 and 22 can result in three transcripts: p190, p210 or p230. BCR primer can be used to transcript identification since mutations may be present in the patient’s sample (Chasseriau et al., 2004). Gene break point determines its classification as major (M-BCR), lower (m-BCR) and micro (μ-BCR). Transcripts have different sizes and share the same fraction responsible for encoding tyrosine kinase, which is involved in leukemogenesis (Davis et al., 1985).

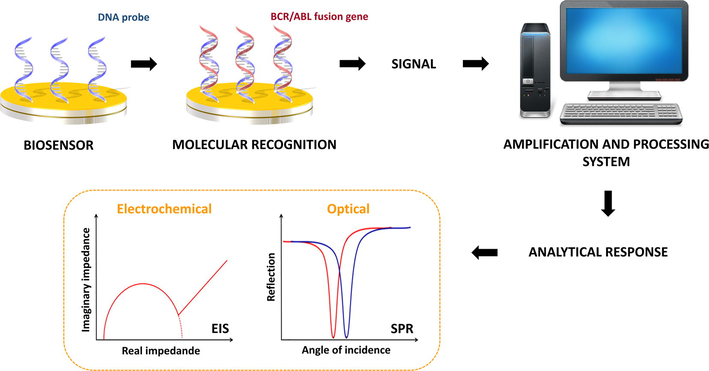

Most Ph + CML patients (>95%) exhibit a breakpoint in the M-BCR region. Two points of more frequent breaks in this region occur after 13th exon in b2a2 (e13a2) fusion or after 14th exon resulting in b3a2 (e14a2) fusion. The fusion of the mRNA is translated into transcripts in p210BCR/ABL protein (Gabert et al., 2003).m-BCR region breakpoint results in e1a2 junction, which is translated into a p190BCR/ABL protein present in ALL (Sawyers, 1999). p230BCR/ABL is composed by 90% of p160 BCR constituents due to the breaking point located in the 3′ end of the BCR (BCR-μ region). The transcript is related to neutrophil maturation in CML (Deininger et al., 2000). In addition, there are reports of CML patients presenting other proteins (p190BCR/ABL or p230BCR/ABL). The most common breakpoint regions in c-ABL gene is the 5′ of the second exon (a2 junctions) and between the second and third exon (a3 junctions) (Radich, 2000). The choice of the primer to be used on the sensor platform vary according to the size of the transcribed gene breakpoint. Table 1 shows primers used for amplification of the BCR and ABL genes.b1 exon (e12) belongs to BCR gene and amplifies all variants of the m-BCR. Specific primers for E1 and E19 are related to the minor and micro BCR regions. Some ABL primers are specific for exon 3 and detect junctions for a2 and a3. The probes’ specificity allow identify subtle differences in genome sequences and can be effectively applied in the development of genosensors (Furukawa et al., 1993; Ross et al., 2008). A schematic representation of the probes construction for BCR/ABL fusion gene (b3a2/e14a2) is showed in Fig. 3.

Sequence (5′-3′)

Application (Gene)

GCTTCACACCATTCCCCATT

a3 primer (ABL)

TGGAGGAGGTGGGCATCTAC

e1 primer (BCR)

GCAGAGTGGAGGGAGAACAT

E12 (b1) primer (BCR)

CCTCGCAGAACTCGCAACAG

e19 primer (BCR)

Oligonucleotide probe and target sequences of BCR/ABL b3a2(e14a2) junction for BCR and ABL genes. Normal sequences are used as negative target control to evaluate the probe specificity. 5′-funcionalization of the probe (thiolation or amination) ensure its chemical immobilization on the sensor platform surface.

3 Strategies for genosensors development

The technological development in nanoscience allowed the construction of biodevices based on biomolecules with high analytical performance (Kirsch et al., 2013; Vashist et al., 2012). Biosensors are a cutting-edge technology with high efficiency and commercial applicability. In addition, biosensors have been able to improve the field of clinical diagnostics (Jain, 2016). Faced with the limitations of conventional methods, the biosensors arise as an effective alternative for BCR/ABL fusion gene diagnosis (Chen et al., 2015; Matsishin et al., 2016). The main techniques used for molecular diagnosis of the BCR/ABL fusion gene are sensitive, however some obstacles to its widespread use are present as expensive instrumentation and time-consuming analysis (Chen et al., 2008a; Sharma et al., 2012b).

Therefore, genosensors differ from other biosensitive systems due to their reusability and specificity, since immobilized DNA probe should be able to discriminate as few as a single base-pair mismatch between different DNA targets (Sassolas et al., 2008; Teles and Fonseca, 2008). Although DNA-based biosensors are promising tools for clinical and laboratory use, some obstacles must be overcome, such as poor stability and reproducibility (Chao et al., 2016). Biosensing interface design is the key point for an effective bioanalysis process and obtaining reliable results (Chao et al., 2016; Jia et al., 2016).

DNA probe should be immobilized of predictable manner during genosensor development to maintain its biorecognition capability (Drummond et al., 2003). Independent of molecular identity and conformation of the probe, non-specific adsorption should be minimized and the stability of the anchored biomolecule must be preserved (Liu et al., 2012; Lucarelli et al., 2008). The orientation and accessibility of the DNA probe are essential to ensure the affinity to DNA target and hybridization efficiency (Lucarelli et al., 2008). The control of these steps ensures the high sensitivity and selectivity of the biosensor (Liu et al., 2012).

The immobilization methods employed in the development of genosensors are based on physical methods (for example, adsorption), chemical methods (via covalent binding) and biointeraction processes (e.g., the use of biotin and avidin to anchoring of biomolecules) (Campàs and Katakis, 2004). The adsorption of the DNA probes on solid surfaces is based on ionic interactions between negatively charged phosphate groups of the DNA molecule and positively charged substrate (Sassolas et al., 2008). This method is a simple way for DNA immobilization and not require any modification in the molecular structure of the nucleic acid.

Chemical immobilization of DNA probes on different supports is one of the main methodologies used in the construction of biosensors (Abdul Rasheed and Sandhyarani, 2016). Chemical immobilization reduces the leaching ensuring a greater stability and reproducibility of the sensing layer (Sassolas et al., 2008). Chemisorption for the attachment of thiolated DNA molecules on gold surfaces have been extensively used (Li et al., 2013; Lin et al., 2007; Mannelli et al., 2005; Steel et al., 2000; Wang et al., 2009). The chemisorption is based on the strong affinity between sulfur and gold atoms, which allows the formation of covalent bonds (Sassolas et al., 2008). Covalent immobilization of DNA probes on functionalized surfaces can be performed through coupling agents, such as glutaraldehyde, N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) and 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC) (Lin et al., 2007; Zhong et al., 2014). In this case, intrinsic or synthetic chemical groups of the DNA molecule specifically react with functional groups of the previously activated substrate by coupling agents (Sassolas et al., 2008).

Other method for DNA attachment is based on affinity between biomolecules. For example, biotin and avidin molecules (or streptavidin) are widely used in the construction of biosensors, since they form complexes with high affinity (Kim and Choi, 2014). DNA probes can be biotinylated by chemical synthesis and subsequently immobilized on surfaces modified with avidin (or streptavidin). The biointeraction process between biotinylated DNA probes and avidin (or streptavidin) enables the specific orientation of the immobilized DNA (Dong et al., 2015).

The attachment protocol is strictly dependent on the characteristics of the transducing surfaces and interface materials (Liu et al., 2012; Lucarelli et al., 2008). Moreover, the immobilization method chosen for the development of DNA biosensors should reduce the electrostatic repulsion and steric hindrance between DNA strands, avoiding desorption and ensuring the structural conformation of the biomolecule (Campàs and Katakis, 2004; Lucarelli et al., 2008).

4 Electrochemical genosensors for Bcr/Abl detection

Diverse methods for signal transduction can be used to characterize the hybridization process (Hu et al., 2014; Lin et al., 2009; Matsishin et al., 2016). Recently, an increasing number of electrochemical genosensors for specific detection of the BCR/ABL fusion gene have been reported (Chen et al., 2008a, 2015; Lin et al., 2009; Malecka et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2014; Yang and Zhang, 2014).

The construction of the electrochemical DNA biosensors is based on the immobilization of nucleic acids on electrochemical transducers (Kagan et al., 2004; Perumal and Hashim, 2014). DNA electrochemical detection is related to the measurement of electrical parameters as current, potential, conductance, impedance and capacitance (Teles and Fonseca, 2008). Electrochemical devices have advantages as fast detection, simplicity, sensitivity, selectivity and low cost (Chao et al., 2016; Kagan et al., 2004).

The main electrochemical techniques used to monitor the interfacial analytical processes during detection of the BCR/ABL fusion gene are cyclic voltammetry (CV) (Wang et al., 2014), differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) (Lin et al., 2007; Sharma et al., 2012b), anodic stripping voltammetry (ASV) (Hu et al., 2013) and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) (Yang and Zhang, 2014; Zhong et al., 2014) (Table 2).

Sensor platform

Detection technique

Detection time

Detection limit (M)

Reference

Gold surface/thiolated DNA probe (were used amplification probes and CdSeTe/CdS quantum dots tagging)

ASVa

∼18.5 h

2 × 10−15

(Hu et al., 2013)

ITO coated glass substrate/nanostructured composite of chitosan and cadmium-telluride quantum dots/aminated DNA probe

CVb and DPVc

1 min

2.56 × 10−12

(Sharma et al., 2012b)

Glassy carbon surface/chitosan/cerium dioxide nanoparticles/multiwalled carbon nanotubes/AuNPs/thiolated DNA probe

CV and DPV

55 min

5 × 10−13

(Li et al., 2013)

Gold surface/thiolated DNA probe (reporter probe labeled biotin)

CV and EISd

60 min

10 × 10−15

(Wang et al., 2009)

Gold surface/DNA probe (thiolatedhairpin locked nucleic acids)

CV, EIS and DPV

∼60 min

1.20 × 10−10

(Lin et al., 2009)

Glassy carbon electrode/graphene sheets/polyaniline/AuNPs/thiolated DNA probe

CV, EIS and DPV

∼90 min

1.05 × 10−12

(Chen et al., 2015)

Glassy carbon surface /graphene sheets/chitosan/polyaniline/AuNPs/functionalized hairpin DNA probe (5′-SH and 3′-biotin)

CV, EIS and DPV

∼150 min

2.11 × 10−12

(Wang et al., 2014)

Glassy carbon surface/aminated DNA probe (isorhamnetin used as electrochemical indicator)

CV, EIS and DPV

35 min

3 × 10−12

(Zhong et al., 2014)

Glassy carbon surface/poly-eriochrome black T film/AuNPs/DNA probe (thiolated hairpin locked nucleic acids)

CV, EIS and DPV

∼60 min

1 × 10−13

(Lin et al., 2010)

Glassy carbon surface/sulfonic-terminated aminobenzenesulfonic acid/aminated DNA probe (18-mer locked nucleic acids)

CV, EIS and DPV

∼35 min

9.40 × 10−13

(Chen et al., 2008a)

Gold surface/AuNPs/DNA probe (thiolated hairpin locked nucleic acids)

CV, EIS and DPV

∼60 min

1 × 10−10

(Lin et al., 2011)

ITO coated glass substrate/tri-n-octylphosphine oxide-capped cadmium selenide quantum dots/thiolated DNA probe

DPV

2 min

10 × 10−15 M

(Sharma et al., 2012a)

Glassy carbon surface/aminated DNA probe (methylene blue used as electrochemical indicator)

DPV

35 min

5.90 × 10−8

(Lin et al., 2007)

Carbon paste surface /FePt nanoparticle-decorated electrochemically reduced graphene oxide/DNA probe

EIS

–

2.60 × 10−15

(Yang and Zhang, 2014)

Gold surface/hybrid composite of AuNPs and polyaniline/DNA probe

CV and EIS

15 min

69.40 × 10−18

(Avelino et al., 2016)

ITO coated glass substrate/silane/cadmium-telluride quantum dots/aminated DNA probe

CV and DPV

–

1 × 10−12

(Sharma et al., 2013)

Glassy carbon surface/aminated DNA probe (sodium tanshinone IIA sulfonate used as electrochemical indicator)

CV and DPV

30 min

6.70 × 10−9

(Chen et al., 2008b)

Glassy carbon surface/aminated DNA probe (2-nitroacridone used as electrochemical indicator)

CV and DPV

30 min

6.70 × 10−9

(Chen et al., 2008c)

ITO coated glass substrate/amino-functionalized silica coated zinc oxide nanoparticles/aminated DNA probe

CV and EIS

–

1 × 10−16

(Pandey et al., 2016)

Glassy carbon surface/1-aminopyrene and graphene hybrids/aminated DNA probe

CV and EIS

40 min

4.5 × 10−13

(Luo et al., 2013)

Gold surface/thiolated DNA probe (blocking solution: 6-Mercapto-1-hexanol)

SPRe

10 min

–

(Matsishin et al., 2016)

Gold surface/thiolated DNA probe (blocking solution: 6-Mercapto-1-hexanol)

SPRif

20 min

1.03 × 10−8

(Wu et al., 2016)

Gold surface/1-octadecanethiol/tri-n-octylphosphine oxide capped cadmium selenide quantum dots/thiolated DNA probe

SPR

30 min

4.21 × 10−12

(Ghrera et al., 2016)

Cadmium-telluride quantum dots functionalized with carboxylic groups/aminated DNA probe

FRETg

20 min

1.50 × 10−10

(Shamsipur et al., 2017)

DNA machineries based on tailored DNA probes to for detect target, form appropriate nanostructure and produce DNAzyme subunits

Chemiluminescence

110 min

23 × 10−15

(Xu et al., 2016)

Voltammetry is an analytical methods that provides information about analyte through electrical currents obtained from a potential variation (Luna et al., 2015). Voltammetry technique can be subdivided, according to the potential variation, as polarography, linear sweep, differential staircase, normal pulse, reverse pulse, differential pulse and others (Gupta et al., 2011). Voltammetric experiments involve the use of an electrochemical cell with three electrodes: (1) working electrode, (2) auxiliary electrode or counter electrode and (3) reference electrode. The current generated in the system is measured between the working electrode and the auxiliary electrode, while the voltage is measured between the working electrode and the reference electrode (Grieshaber et al., 2008). Voltammetry is graphically represented by voltammograms (current vs. potential) and provide information about the charge transfer kinetics, reversibility of electrochemical reactions, redox potentials of electroactive substances, adsorption and chemical immobilization of substances/biomolecules (Avelino et al., 2014; Nicholson, 1965).

EIS is based on the application of a small amplitude sinusoidal signal (continuous voltage) to the working electrode in a system at equilibrium. On the same electrode is superimposed an alternating signal in the form of different frequency values (Bott, 2001; Macdonald, 1990) and, consequently, an alternating current is generated in the electrochemical cell (Suni, 2008). The impedance Z is then calculated as the ratio between voltage-time function V(t) and resulting current-time function I(t), considering different excitation frequencies (angular frequencies) (Katz and Willner, 2003). The impedance values correspond to complex numbers composed by a real component (Zre or Z′) and an imaginary component (Zim or Z″), being related to the resistance and capacitance of the electrochemical system, respectively (Katz and Willner, 2003; Macdonald, 1990; Suni, 2008). In addition, equivalent circuit models are used for theoretical simulation of the experimental results and interpretation of the impedance spectra (Bott, 2001; Katz and Willner, 2003). By monitoring the electrical properties (conductance, capacitance and resistance to charge transfer) is possible define molecular events in the double layer with high accuracy (Oliveira et al., 2011; Park and Park, 2009). EIS is a valuable strategy for understanding interfacial phenomena as biorecognition processes on the surface of modified electrodes (Bahadir and Sezginturk, 2016; Katz and Willner, 2003; Park and Park, 2009).

The first biosensor for detection of the BCR/ABL fusion gene was obtained from direct anchoring of the DNA probe on the electrochemical transducer. Lin et al. (2007) developed a biosensor for BCR/ABL fusion gene based on covalent immobilization of the DNA probe with terminal amino groups on glassy carbon surface. NHS and EDC were used as coupling agents and methylene blue as chemical indicator. The proposed biosensor showed a calibration range between 1.25 × 10−7 M and 6.75 × 10−7 M, with a detection limit of 5.9 × 10−8 M (Lin et al., 2007). Similar biosensor for specific detection of BCR/ABL fusion gene was developed with improved analytical sensitivity, differing in the use of isorhamnetin as indicator. The biodevice exhibited a linear calibration range from 50 × 10−8 M to 10 × 10−12 M, with a detection limit of 3 × 10−12 M (Zhong et al., 2014). Other electrochemical indicators as sodium tanshinone IIA sulfonate (Chen et al., 2008b) and 2-nitroacridone have been used (Chen et al., 2008c). The proposed system showed low sensitivity with a detection limit of 6.7 × 10−8 M.

The immobilization technique based on thiol-modified DNA probes on gold transducers for obtaining self-assembly monolayers has been extensively used. Lin et al. (2009) constructed a new biosensor using thiolated hairpin locked nucleic acids (LNA) as a capture probe for BCR/ABL fusion gene. The biosensitive system showed excellent specificity for single-base mismatch with a detection limit of 1.2 × 10−10 M (Lin et al., 2009). In addition, Wang et al. (2009) developed a sandwich-type electrochemical biosensor for detection of the BCR/ABL fusion gene using LNA. In this case, the detection mechanism involves a pair of probes with a thiolated capture probe immobilized on a gold electrode associated to a reporter probe labeled biotin as an affinity tag for avidin-horseradish peroxidase. The proposed biosensor showed a detection limit of 10 × 10−15 M with satisfactory results for oncogene diagnosis using PCR samples (Wang et al., 2009). Hu et al. (2013) associated the advantages of a circular strand replacement polymerization, cascade hybridization reaction as well as quantum dot for signal amplification aiming to improve the biosensor accuracy. The biosensor showed high sensitivity with detection limit ∼2 × 10−15 M (Hu et al., 2013).

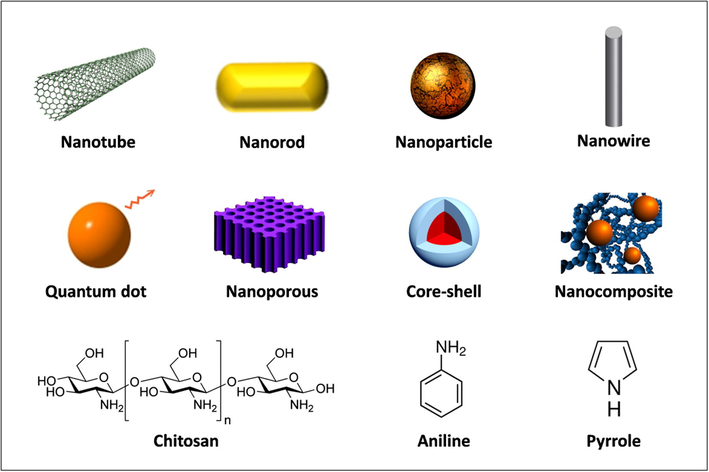

Biocompatible nanostructured platforms arise as an innovative alternative to immobilize DNA probes and therefore obtain smart biosensors with high analytical performance (Patel et al., 2013). Numerous nanostructures can be used to the platform design as nanotubes, nanowires, nanoparticles, nanorods, nanoporous, hybrid nanocomposites, core-shell and quantum dots (Asefa et al., 2009) (Fig. 4). In addition, organic polymers as polyaniline, polypyrrole and chitosan (CHI) can also be employed (Wang et al., 2014).

Schematic representation of the main components used in the development of nanostructured platforms.

Many of these functional materials exhibit differentiated physical and chemical characteristics associated to electrical conductivity, catalytic activity, high surface area, biocompatibility, magnetic properties and chemical stability (Jia et al., 2016). Nanostructured platforms increase the electrochemical active area maximizing the analytical sensitivity and act as scaffolds for biocompatible DNA immobilization. Therefore, they have been widely employed for BCR/ABL fusion gene detection (Table 2) (Chen et al., 2015; Jia et al., 2016; Li et al., 2013; Teles and Fonseca, 2008).

Sulfonic-terminated aminobenzenesulfonic acid is an alternative for the development of BCR/ABL detection system based on capture probe. A capture probe (18-mer locked, nucleic acid-modified) with free amines groups covalently attached on sulfonic-terminated aminobenzenesulfonic acid monolayer-modified glassy carbon electrode via acyl chloride cross-linking reaction was developed (Chen et al., 2008a). Methylene blue is applied as electroactive indicator to monitor the hybridization process between the capture probe and DNA target. This platform showed specificity for single-base mismatch and complementary double-stranded DNA after hybridization with a detection limit of 9.4 × 10−13 M (Chen et al., 2008a).

Electropolymerization of poly-eriochrome black T on glassy carbon electrode followed by electrodeposition of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) was effectively used for BCR/ABL fusion gene identification. In this case, a capture probe (thiolated hairpin locked nucleic acids) was anchored on AuNPs and methylene blue (used as hybridization label) resulting in a detection limit of 1 × 10−13 M (Lin et al., 2010).

Benzoate binuclear copper (II) complex (CuR2) was used as indicator of hybridization in a biosensor based on AuNPs and thiolated hairpin locked nucleic acids (as capture probe). The proposed assay quantified BCR/ABL fusion gene over the range of 1 × 10−7 to 1 × 10−9 M with a detection limit of 1 × 10−10 M. CuR2 was able to binding DNA through intercalation due to their geometrical structure and physicochemical properties (Lin et al., 2011).

CHI and cadmium-telluride quantum dots onto indium-tin-oxide (ITO) coated glass substrate was used to obtain a hybrid platform based on electrophoretic deposition. DNA probe with terminal NH2 group was immobilized onto modified ITO electrode using glutaraldehyde as a cross-linker. The biosensor differentiate between cDNA samples of CML positive and negative patients at low concentrations (2.56 × 10−12 M) with reuse about 5–6 tests under stored at 4 °C for 6 weeks (Sharma et al., 2012b).

Langmuir–Blodgett (LB) technique can be an efficient strategy for construction of detection systems. Sharma et al. developed a sensor platform based on LB monolayers of tri-n-octylphosphine oxide-capped cadmium selenide quantum dots onto ITO coated glass substrate under covalent immobilization of thiolated DNA probes (via Cd-thiol affinity). The proposed biosensor was reused about 8 times, shelf life of 2 months and detection limit of 10 × 10−15 M with fast time response of 120 s (Sharma et al., 2012a).

A sensing interface based on silane (cross-linker agent) and cadmium-telluride quantum dots was reported for BCR/ABL gene detection. Covalent immobilization of amine terminated DNA probes on quantum dots surface allowed the identification of target oligonucleotides in concentration range from 1 × 10−6 to 1 × 10−12 M within 30 min (Sharma et al., 2013).

Pandey et al. described a controlled deposition of amino-functionalized silica-coated zinc oxide nanoparticles onto ITO coated glass substrate using LB technique. Electrodes were used to detect BCR/ABL fusion gene through covalent immobilization of aminated DNA probes. The study demonstrated that molecular organization contributes to the increased sensitivity of the biosensor with a detection limit of 1 × 10−16 M. The biosensor was able to distinguish CML positive patient samples (Pandey et al., 2016).

A more complex system composed by AuNPs, multiwalled carbon nanotubes, cerium dioxide nanoparticles and CHI composite membrane was developed. The biosensor was based on a capture probe attached onto nanocomposite membrane and hybridization process mediated by methylene blue (electroactive indicator). The method was applied for oncogene detection in PCR real samples with analytical sensitivity of 5 × 10−13 M. The proposed biosensor had a storage time of one month and 10 cycles of regeneration and hybridization (Li et al., 2013).

Wang et al. developed a biosensor using graphene sheets, CHI, polyaniline, AuNPs and hairpin structure as a probe doubly functionalized with a 5′-SH and a 3′-biotin. The biodetection was based on the use of a streptavidin-alkaline phosphatase bound to the biosensor surface through the interaction between biotin/streptavidin. The phosphatase enzyme catalyzes the hydrolysis of the electroinactive 1-naphthyl phosphate to 1-naphthol, which could amplify the electrochemical response with a linear detection range of 1 × 10−9 to 1 × 10−11 M. The biosensor was used for real-time detection of the BCR/ABL fusion gene in PCR products from clinical samples with satisfactory results (Wang et al., 2014).

An indicator-free impedimetric biosensor based on FePt nanoparticle-decorated electrochemically reduced graphene oxide (ERGNO) was developed for identification of the BCR/ABL fusion gene with a detection limit of 2.6 × 10−15 M. The proposed DNA biosensor was effectively used for detection in real blood samples (Yang and Zhang, 2014).

A DNA circuit based on graphene sheets, polyaniline and AuNPs was developed for BCR/ABL fusion gene detection. In detail, a transducer hairpin was designed to obtain a universal DNA circuit with favorable signal-to-background ratio and to enable reuse of the DNA circuit for different inputs DNA with linear response (2 × 10−8 to 1 × 10−11 M) and detection limit of 1.05 × 10−12 M (Chen et al., 2015).

Luo et al. described a novel protocol for preparation of 1-aminopyrene/graphene hybrids. Amino-substituted oligonucleotide probes were conjugated to hybrids for manufacturing a label-free electrochemical biosensor. Under optimum conditions (35 °C, pH 7.4 and hybridization time of 40 min), BCR/ABL fusion gene can be quantified in a wide range of 1 × 10−8 to 1 × 10−12 M with good linearity and low detection limit (Luo et al., 2013).

BCR/ABL fusion gene detection was improved to a concentration as low as 69.4 × 10−18 M. The detection limit refers to the concentration of recombinant plasmids containing BCR/ABL fusion gene (69.4 × 10−18 M or 41 DNA copies per μL). The label-free biodetection system used in this assay was based on a hybrid composite of AuNPs and polyaniline for self-amplification of the electrochemical signal. A capture DNA probe was attached on gold electrode modified with hybrid composite through electrostatic interactions to obtain the sensor layer. The developed system displayed an excellent specificity and ability to discriminate between CML positive and negative samples. Moreover, demonstrated high sensitivity for leukemia diagnosis and monitoring of minimal residual disease (Avelino et al., 2016).

5 Optical genosensors for BCR/ABL detection

It is worthwhile to mention that new strategies for BCR/ABL diagnosis have been based on surface plasmon resonance (SPR) technology. SPR is a label-free technique that allows an indirect analysis of the sample by light refraction (Boozer et al., 2003; Nelson et al., 2002). SPR involves the interaction between electromagnetic waves of incident light and free-electron systems of a conductive surface. The incident light is placed at a fixed angle. The position of the resonance angle is sensitive to the refractive index of the medium adjacent to the metal surface. Each material has an intrinsic refractive index and its presence in the region adjacent to the surface (where the light is reflected) results in a detectable evanescent wave. The difference in refractive index creates different SPR responses. The evanescent wave from the incident light couples to the oscillating free electrons (plasmons) on the metal surface and then the surface is resonantly excited. Then, the energy of the incident light is lost, reduces the intensity of the reflected light and is detected by a set of photodiodes or detector (charge coupled detector, CCD) (Singh, 2016).

SPR has advantages as monitoring the dynamic processes on the sensor platform surface, determination of dielectric properties (adsorption and extension rate), kinetic association/dissociation and affinity constants. Recently, Matsihin et al. developed two strategies based on the ionic strength decrease of the hybridization buffer and temperature elevation to obtain a SPR sensor for BCR and BCR/ABL genes. The proposed biosensor was able to discriminate a complete (at 50 °C) to a partial hybridization (at 40 °C) between probe, DNA target and negative control (Matsishin et al., 2016).

Other study included the deposition of tri-n-octylphosphine oxide capped cadmium selenide quantum dots (QD) on SPR disk surface through LB technique. Thiol-terminated DNA probe sequence was covalently immobilized to detect the change-coupling angle via hybridization. The biosensor constructed with DNA sequence probe for CML presented high sensitivity with detection limit of 4.21 pM (Ghrera et al., 2016).

In addition, QD were also applied to develop a high sensitive, simple, and low-cost FRET-based QDs-DNA nanosensor for BCR/ABL gene determination in CML samples. The mechanism was based on FRET between QDs (a donor) in DNA probe and MB (as acceptor and DNA intercalator). The enhancement of the MB emission intensity was used to follow up the hybridization, which was proportional to DNA concentration. The detection limit of the proposed method was 1.5 × 10−10 M. This study was innovative since presented a new sensor platform and used real CML patient samples (Shamsipur et al., 2017).

SPR imaging (SPRi) can be an alternative for biosensors development since it can be used to capture images of the local changes at the surface and provide detailed information on kinetic processes, biomolecular interactions and molecular binding (Wang et al., 2013). The processes can be monitored by detection of pixel intensity change. The variation of the reflected light intensity is proportional to the refractive index changes due to molecular binding. SPRi devices have been developed to implement hybridization-based sensing, including miRNA/DNA detection, bacterial genotyping and SNP identification (Gorodkiewicz et al., 2011).

SPRi was used to develop a custom-made intensity-interrogation surface plasmon resonance imaging system to directly detect a specific sequence of BCR/ABL in CML. The variation of reflected light intensity detected from the sensor chip composed of gold islands array was proportional to the change of refractive index due to the selective hybridization of surface-bound DNA probes with target ssDNA. The detection limit of the SPRi measurement is ∼10.29 × 10−9 M. This study demonstrated a nucleic acid-based SPRi biosensor as an alternative high-effective, high-throughput label-free tool for DNA detection in biomedical research and molecular diagnosis (Wu et al., 2016).

On the other hand, Xu et al. (2016) developed a novel imaging method using DNAzyme-driven chemiluminescence (CL) based on bis-three-way junction (bis-3WJ) nanostructure and cascade DNA machineries. Bis-3WJ probes were designed to recognize specifically BCR/ABL fusion gene that forms a stable bis-3WJ nanostructure for activation of polymerase/nicking enzyme machineries in cascade. The resulting products formed an integrated DNAzyme by self-assembly to catalyze CL substrate and provided an amplified signal for sensing events. This platform achieved ultrasensitive BCR/ABL gene detection of ∼23 fM. It also offered an excellent discrimination ability toward target of seven orders of magnitude. The biosensing strategy also possessed merits such as homogeneous, isothermal and label-free assay system (Xu et al., 2016).

6 Conclusion and prospects

In this review, optical and electrochemical techniques were effective applied to obtain information about molecular phenomena associated to sensor assembly and bioaffinity process. The appropriate design of DNA probes and their immobilization on solid surfaces are a key point for biosensors development with high accuracy. The development of portable devices is essential for clinical and commercial application. However, the biosensors discussed in this review are in preliminary stages for prototypes development. Nanostructured platforms provided an effective environment for bioreceptor anchoring due to a larger electroactive area and improvement of the interfacial electron transfer. Both electrochemical (10−8 M to 10−18 M) and optical (10−8 M to 10−15 M) techniques were able to identify BCR/ABL fusion gene at very low concentrations. In general, BCR/ABL fusion gene detection is based on cDNA analysis. Genomic DNA is not widely used due to the presence of long introns in BCR sequence. The common breakpoints of the M- and m-BCR regions involve e13a2, e14a2 and e1a2 fusion variants. Adequate amounts of blood are required to obtain cDNA samples, characterizing a limitation for reverse transcription technique (conversion of RNA to cDNA) and biosensors. However, is expected that the innovation associated to the smart biosensors development allows the identification of cancer at early stage, minimal residual disease monitoring and improvement of the quality of life of leukemia patients.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the support of the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development/CNPq (grant 302885/2015-3 and 302930/2015-9) and MCT/FINEP.

References

- Quartz crystal microbalance genosensor for sequence specific detection of attomolar DNA targets. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2016;905:134-139.

- [Google Scholar]

- Trends in nanotechnology patents applied to the health sector. Recent Pat. Nanotech.. 2012;6(1):29-43.

- [Google Scholar]

- The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood. 2016;127(20):2391-2405.

- [Google Scholar]

- Recent advances in nanostructured chemosensors and biosensors. Analyst. 2009;134(10):1980-1990.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biosensor based on hybrid nanocomposite and CramoLL lectin for detection of dengue glycoproteins in real samples. Synth. Met.. 2014;194:102-108.

- [Google Scholar]

- Attomolar electrochemical detection of the BCR/ABL fusion gene based on an amplifying self-signal metal nanoparticle-conducting polymer hybrid composite. Colloids Surf. B, Biointerfaces. 2016;148:576-584.

- [Google Scholar]

- A review on impedimetric biosensors. Artificial Cells, Nanomed. Biotechnol.. 2016;44(1):248-262.

- [Google Scholar]

- The chronic myelogenous leukemia specific P210-protein is the product of the BCR/ABL hybrid gene. Science. 1986;233(4760):212-214.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comprehensive analysis of BCR/ABL variants in chronic myeloid leukemia patients using multiplex RT-PCR. Clin. Lab.. 2012;58(5–6):433-439.

- [Google Scholar]

- Role of chromosomal aberrations in clonal diversity and progression of acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2015;29(6):1243-1252.

- [Google Scholar]

- Surface functionalization for self-referencing surface plasmon resonance (SPR) biosensors by multi-step self-assembly. Sensors Actuators B: Chem.. 2003;90(1–3):22-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Electrochemical techniques for the characterization of redox polymers. Curr. Sep.. 2001;19(3):71-75.

- [Google Scholar]

- Real-time quantitative PCR analysis can be used as a primary screen to identify patients with CML treated with imatinib who have BCR-ABL kinase domain mutations. Blood. 2004;104(9):2926-2932.

- [Google Scholar]

- DNA biochip arraying, detection and amplification strategies. TrAC, Trends Anal. Chem.. 2004;23(1):49-62.

- [Google Scholar]

- Electrochemical genosensors for the detection of cancer-related miRNAs. Anal. Bioanal. Chem.. 2014;406(1):27-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- Philadelphia Chromosome Symposium: commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the discovery of the Ph chromosome. Cancer genetics. 2011;204(4):171-179.

- [Google Scholar]

- Characterization of the different BCR-ABL transcripts with a single multiplex RT-PCR. J. Mol. Diagn.: JMD. 2004;6(4):343-347.

- [Google Scholar]

- Electrochemical biosensor for detection of BCR/ABL fusion gene using locked nucleic acids on 4-aminobenzenesulfonic acid-modified glassy carbon electrode. Anal. Chem.. 2008;80(21):8028-8034.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hybridization biosensor using sodium tanshinone IIA sulfonate as electrochemical indicator for detection of short DNA species of chronic myelogenous leukemia. Electrochim. Acta. 2008;53(6):2716-2723.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hybridization biosensor using 2-nitroacridone as electrochemical indicator for detection of short DNA species of Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia. Biosens. Bioelectron.. 2008;24(3):349-355.

- [Google Scholar]

- Coupling a universal DNA circuit with graphene sheets/polyaniline/AuNPs nanocomposites for the detection of BCR/ABL fusion gene. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2015;889:90-97.

- [Google Scholar]

- Flow cytometric immunophenotyping for hematologic neoplasms. Blood. 2008;111(8):3941-3967.

- [Google Scholar]

- Activation of the c-abl oncogene by viral transduction or chromosomal translocation generates altered c-abl proteins with similar in vitro kinase properties. Mol. Cell Biol.. 1985;5(1):204-213.

- [Google Scholar]

- Polymerase Chain Reaction. In: Dijkstra J., de Jager C.P., eds. Practical Plant Virology: Protocols and Exercises. Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 1998. p. :415-425.

- [Google Scholar]

- Electrochemical DNA Biosensor Based on a Tetrahedral Nanostructure Probe for the Detection of Avian Influenza A (H7N9) Virus. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2015;7(16):8834-8842.

- [Google Scholar]

- Heterogeneous immunosensing using antigen and antibody monolayers on gold surfaces with electrochemical and scanning probe detection. Anal. Chem.. 2000;72(11):2371-2376.

- [Google Scholar]

- Breast and cervical cancer in 187 countries between 1980 and 2010. Lancet. 2012;379(9824):1390-1391.

- [Google Scholar]

- Detection of BCR-ABL fusion mRNA in chronic myelogenous leukemia by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction using nested primers. Osaka City Med. J.. 1993;39(1):35-45.

- [Google Scholar]

- Standardization and quality control studies of ‘real-time’ quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction of fusion gene transcripts for residual disease detection in leukemia – A Europe Against Cancer Program. Leukemia. 2003;17(12):2318-2357.

- [Google Scholar]

- Quantum dot monolayer for surface plasmon resonance signal enhancement and DNA hybridization detection. Biosens. Bioelectron.. 2016;80:477-482.

- [Google Scholar]

- Development of an SPR imaging biosensor for determination of cathepsin G in saliva and white blood cells. Mikrochim. Acta. 2011;173(3–4):407-413.

- [Google Scholar]

- Electrochemical biosensors – Sensor principles and architectures. Sensors. 2008;8(3):1400-1458.

- [Google Scholar]

- Oncogenic role of fusion-circRNAs derived from cancer-associated chromosomal translocations. Cell. 2016;165(2):289-302.

- [Google Scholar]

- Voltammetric techniques for the assay of pharmaceuticals—A review. Anal. Biochem.. 2011;408(2):179-196.

- [Google Scholar]

- Predicting interactome network perturbations in human cancer: application to gene fusions in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2014;25(24):3973-3985.

- [Google Scholar]

- The impact of biosensors on the clinical laboratory. MLO: Med. Lab. Obs.. 1990;22(7):32-35.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ultrasensitive electrochemical detection of BCR/ABL fusion gene fragment based on polymerase assisted multiplication coupling with quantum dot tagging. Electrochem. Commun.. 2013;35:104-107.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ultrasensitive electrochemical biosensor for detection of DNA from bacillus subtilis by coupling target-induced strand displacement and nicking endonuclease signal amplification. Anal. Chem.. 2014;86(17):8785-8790.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pathology of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: an update. Ann. Diagn. Pathol.. 2007;11(5):363-389.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nanobiosensors: a review of its design and clinical applications. Res. J. Pharm. Dosage Forms Technol.. 2016;8(1):37-45.

- [Google Scholar]

- Engineering the bioelectrochemical interface using functional nanomaterials and microchip technique toward sensitive and portable electrochemical biosensors. Biosens. Bioelectron.. 2016;76:80-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chapter 3 - Real-Time PCR. In: Conn P.M., ed. Methods Cell Biol.. Academic Press; 2012. p. :55-68.

- [Google Scholar]

- Recent trends in electrochemical DNA biosensor technology. Meas. Sci. Technol.. 2004;15(2):R1.

- [Google Scholar]

- Techniques of molecular biology in morphological diagnosis of DNA and RNA viruses. Folia histochemica et cytobiologica/Polish Academy of Sciences. Polish Histochemical Cytochem. Soc.. 2001;39(2):97-98.

- [Google Scholar]

- Probing biomolecular interactions at conductive and semiconductive surfaces by impedance spectroscopy: routes to impedimetric immunosensors, DNA-sensors, and enzyme biosensors. Electroanalysis. 2003;15(11):913-947.

- [Google Scholar]

- A lipid-based method for the preparation of a piezoelectric DNA biosensor. Anal. Biochem.. 2014;458:1-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biosensor technology: recent advances in threat agent detection and medicine. Chem. Soc. Rev.. 2013;42(22):8733-8768.

- [Google Scholar]

- Electrochemical nucleic acid-based biosensors: Concepts, terms, and methodology (IUPAC Technical Report) Pure Appl. Chem.. 2010;82(5):1161-1187.

- [Google Scholar]

- Electrochemical determination of BCR/ABL fusion gene based on in situ synthesized gold nanoparticles and cerium dioxide nanoparticles. Colloids Surf. B, Biointerfaces. 2013;112:344-349.

- [Google Scholar]

- Construction of a competitor for BCR-ABL cDNA by recombinant PCR. Zhonghua yi xue yi chuan xue za zhi = Zhonghua yixue yichuanxue zazhi = Chinese journal of medical genetics. 1998;15(3):143-146.

- [Google Scholar]

- Electrochemical biosensor based on nanogold-modified poly-eriochrome black T film for BCR/ABL fusion gene assay by using hairpin LNA probe. Talanta. 2010;80(5):2113-2119.

- [Google Scholar]

- Locked nucleic acids biosensor for detection of BCR/ABL fusion gene using benzoate binuclear copper (II) complex as hybridization indicator. Sensors Actuators B: Chem.. 2011;155(1):1-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Electrochemical biosensor for detection of BCR/ABL fusion gene based on hairpin locked nucleic acids probe. Electrochem. Commun.. 2009;11(8):1650-1653.

- [Google Scholar]

- Electrochemical DNA biosensor for the detection of short DNA species of Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia by using methylene blue. Talanta. 2007;72(2):468-471.

- [Google Scholar]

- Development of electrochemical DNA biosensors. TrAC, Trends Anal. Chem.. 2012;37:101-111.

- [Google Scholar]

- Three-dimensional electrochemical immunosensor for sensitive detection of carcinoembryonic antigen based on monolithic and macroporous graphene foam. Biosens. Bioelectron.. 2014;65C:281-286.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cell-based biosensors and their application in biomedicine. Chem. Rev.. 2014;114(12):6423-6461.

- [Google Scholar]

- Electrochemical and piezoelectric DNA biosensors for hybridisation detection. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2008;609(2):139-159.

- [Google Scholar]

- Electrochemical immunosensor for dengue virus serotypes based on 4-mercaptobenzoic acid modified gold nanoparticles on self-assembled cysteine monolayers. Sensors Actuators B: Chem.. 2015;220:565-572.

- [Google Scholar]

- Label-free electrochemical impedance genosensor based on 1-aminopyrene/graphene hybrids. Nanoscale. 2013;5(13):5833-5840.

- [Google Scholar]

- Review of mechanistic analysis by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy. Electrochim. Acta. 1990;35(10):1509-1525.

- [Google Scholar]

- Electrochemical genosensor based on disc and screen printed gold electrodes for detection of specific DNA and RNA sequences derived from Avian Influenza Virus H5N1. Sensors Actuators B: Chem.. 2016;224:290-297.

- [Google Scholar]

- Direct immobilisation of DNA probes for the development of affinity biosensors. Bioelectrochemistry. 2005;66(1–2):129-138.

- [Google Scholar]

- SPR Detection and discrimination of the oligonucleotides related to the normal and the hybrid BCR-ABL genes by two stringency control strategies. Nanoscale Res. Lett.. 2016;11(1):19.

- [Google Scholar]

- Detection of chimeric BCR-ABL genes in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia by the polymerase chain reaction. Lancet. 1991;337(8749):1055-1058.

- [Google Scholar]

- The diversity of BCR-ABL fusion proteins and their relationship to leukemia phenotype. Blood. 1996;88(7):2375-2384.

- [Google Scholar]

- The emerging complexity of gene fusions in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2015;15(6):371-381.

- [Google Scholar]

- Simple multiplex RT-PCR for identifying common fusion BCR-ABL transcript types and evaluation of molecular response of the a2b2 and a2b3 transcripts to Imatinib resistance in north Indian chronic myeloid leukemia patients. Indian J. Cancer. 2015;52(3):314-318.

- [Google Scholar]

- The impact of translocations and gene fusions on cancer causation. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2007;7(4):233-245.

- [Google Scholar]

- Label-free detection of 16S ribosomal RNA hybridization on reusable DNA arrays using surface plasmon resonance imaging. Environ. Microbiol.. 2002;4(11):735-743.

- [Google Scholar]

- Oncogenic protein interfaces: small molecules, big challenges. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2014;14(4):248-262.

- [Google Scholar]

- Theory and application of cyclic voltammetry for measurement of electrode reaction kinetics. Anal. Chem.. 1965;37(11):1351-1355.

- [Google Scholar]

- Impedimetric immunosensor for electronegative low density lipoprotein (LDL−) based on monoclonal antibody adsorbed on (polyvinyl formal)–gold nanoparticles matrix. Sensors Actuators B: Chem.. 2011;155(2):775-781.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nanomaterials for diagnosis: challenges and applications in smart devices based on molecular recognition. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2014;6(17):14745-14766.

- [Google Scholar]

- Controlled deposition of functionalized silica coated zinc oxide nano-assemblies at the air/water interface for blood cancer detection. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2016;937:29-38.

- [Google Scholar]

- DNA hybridization sensors based on electrochemical impedance spectroscopy as a detection tool. Sensors. 2009;9(12):9513-9532.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biocompatible nanostructured magnesium oxide-chitosan platform for genosensing application. Biosens. Bioelectron.. 2013;45:181-188.

- [Google Scholar]

- Advances in biosensors: Principle, architecture and applications. J. Appl. Biomed.. 2014;12(1):1-15.

- [Google Scholar]

- The detection and significance of minimal residual disease in chronic myeloid leukemia. Medicina. 2000;60(Suppl 2):66-70.

- [Google Scholar]

- Enzyme biosensors for biomedical applications: strategies for safeguarding analytical performances in biological fluids. Sensors. 2016;16(6)

- [Google Scholar]

- Nanotechnology research directions for societal needs in 2020: summary of international study. J. Nanopart. Res.. 2011;13(3):897-919.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reverse transcription with random pentadecamer primers improves the detection limit of a quantitative PCR assay for BCR-ABL transcripts in chronic myeloid leukemia: implications for defining sensitivity in minimal residual disease. Clin. Chem.. 2008;54(9):1568-1571.

- [Google Scholar]

- Letter: A new consistent chromosomal abnormality in chronic myelogenous leukaemia identified by quinacrine fluorescence and Giemsa staining. Nature. 1973;243(5405):290-293.

- [Google Scholar]

- Smart electrochemical biosensors: From advanced materials to ultrasensitive devices. Electrochim. Acta. 2010;55(14):4287-4295.

- [Google Scholar]

- Electrochemical biosensors for glucose based on metal nanoparticles. Trac.-Trend. Anal. Chem.. 2013;42:216-227.

- [Google Scholar]

- Determination of cDNA encoding BCR/ABL fusion gene in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia using a novel FRET-based quantum dots-DNA nanosensor. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2017;966:62-70.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nanopatterned cadmium selenide Langmuir-Blodgett platform for leukemia detection. Anal. Chem.. 2012;84(7):3082-3089.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chitosan encapsulated quantum dots platform for leukemia detection. Biosens. Bioelectron.. 2012;38(1):107-113.

- [Google Scholar]

- Quantum dots self assembly based interface for blood cancer detection. Langmuir: ACS J. Surf. Colloids. 2013;29(27):8753-8762.

- [Google Scholar]

- Optical and dielectric sensors based on antimicrobial peptides for microorganism diagnosis. Front. Microbiol.. 2014;5:443.

- [Google Scholar]

- SPR biosensors: historical perspectives and current challenges. Sensors Actuators B: Chem.. 2016;229:110-130.

- [Google Scholar]

- Immobilization of nucleic acids at solid surfaces: effect of oligonucleotide length on layer assembly. Biophys. J.. 2000;79(2):975-981.

- [Google Scholar]

- Impedance methods for electrochemical sensors using nanomaterials. TrAC, Trends Anal. Chem.. 2008;27(7):604-611.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chromosomal stability and the DNA double-stranded break connection. Nat. Rev. Genet.. 2001;2(3):196-206.

- [Google Scholar]

- The World Health Organization (WHO) classification of tumors of the hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues: an overview with emphasis on the myeloid neoplasms. Chem. Biol. Interact.. 2010;184(1–2):16-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nanotechnology-based biosensors and diagnostics: technology push versus industrial/healthcare requirements. BioNanoScience. 2012;2(3):115-126.

- [Google Scholar]

- High performance spectral-phase surface plasmon resonance biosensors based on single- and double-layer schemes. Opt. Commun.. 2013;291:470-475.

- [Google Scholar]

- A sandwich-type electrochemical biosensor for detection of BCR/ABL fusion gene using locked nucleic acids on gold electrode. Electroanal. 2009;21(10):1159-1166.

- [Google Scholar]

- Graphene sheets, polyaniline and AuNPs based DNA sensor for electrochemical determination of BCR/ABL fusion gene with functional hairpin probe. Biosens. Bioelectron.. 2014;51:201-207.

- [Google Scholar]

- Flow cytometry in the diagnosis of acute leukemia. Semin Hematol.. 2001;38(2):124-138.

- [Google Scholar]

- The human genome project: from mapping to sequencing. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med.. 1998;36(8):511-514.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pre-B acute lymphoblastic leukemia with b3a2 (p210) and e1a2 (p190) BCR-ABL fusion transcripts relapsing as chronic myelogenous leukemia with a less differentiated b3a2 (p210) clone. Leukemia. 1999;13(12):2007-2011.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biosensing of BCR/ABL fusion gene using an intensity-interrogation surface plasmon resonance imaging system. Opt. Commun.. 2016;377:24-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bis-three-way junction nanostructure and DNA machineries for ultrasensitive and specific detection of BCR/ABL fusion gene by chemiluminescence imaging. Scientific reports. 2016;6:32370.

- [Google Scholar]

- Indicator-free impedimetric detection of BCR/ABL fusion gene based on ordered FePt nanoparticle-decorated electrochemically reduced graphene oxide. J. Solid State Electr.. 2014;18(10):2863-2868.

- [Google Scholar]

- Electrochemical lectin-based biosensor array for detection and discrimination of carcinoembryonic antigen using dual amplification of gold nanoparticles and horseradish peroxidase. Sensors Actuators B: Chem.. 2016;235:575-582.

- [Google Scholar]

- Electrochemical biosensor for detection of BCR/ABL fusion gene based on isorhamnetin as hybridization indicator. Sensors Actuators B: Chem.. 2014;204:326-332.

- [Google Scholar]