Translate this page into:

Single cell oil of oleaginous marine microbes from Saudi Arabian mangroves as a potential feedstock for biodiesel production

⁎Corresponding author at: Department of Botany - Faculty of Science, Sohag University, Sohag 82524, Egypt. mohamed.eisa@science.sohag.edu.eg (Mohamed A. Abdel-Wahab) mohamed700906@gmail.com (Mohamed A. Abdel-Wahab)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

This study aims to explore microbes from mangroves in Saudi Arabia for their abilities to produce high level of lipids. Mangroves are seldom investigated for oleaginous microbes. A total of 961 isolates of yeasts and filamentous fungi were isolated from 144 submerged marine samples include: 68 decaying leaves of Avicennia marina, 33 decaying thalli of Zostera marina, 14 decaying pneumatophores of Avicennia marina, 9 crab shells, 8 sediment, 7 decaying thalli of Turbinaria ornata and 5 decaying thalli of Cystoseira myrica. Samples were collected from four mangrove sites: Al-Leith, Jeddah and Yanbu at the Red Sea coast and the Syhat mangroves at the Arabian Gulf coast. Isolated fungi were grouped into 62 morphological types that include: 21 yeasts and 41 filamentous fungi. Fifty-four isolates of thraustochytrids were cultured from the four mangrove sites and were grouped into 22 strains. Two oleaginous yeasts: Hortaea werneckii and Rhodotorula mucilaginosa and four Aurantiochytrium strains produced high dry weight ranged between 32 and 49.3 g/L of which 35.2–62 % lipid and their fatty acid profile were determined using GC/MS. Palmitic acid was the major fatty acid in the lipid of the four thraustochytrid isolates and ranged between 5.71 and 82 % of the total fatty acids, 9-Octadecenamide, (Z)- was the major fatty acid amide in the lipid of the two yeast isolates and two thraustochytrid isolates and ranged between 26.94 and 56.63 %, followed by 13-Docosenamide, (Z)- (20.44–34.99 %) from the same four isolates. Other major lipid compounds were: Hexadecanamide (4.35–7.19 %), Cholestrol (7.24–15.07 %), Butylated Hydroxytoluene (3.46–15.76 %), Octadecanamide (3.95–7.9 %), Phenol, 2-(1,1-dimethylethyl)-5-methyl- (1.78–10.33 %) and Pentadecanoic acid (7.47 %).

Keywords

Heterokonta

Filamentous fungi

Labyrinthulomycetes, molecular phylogenetics

1 Introduction

Fungi as a source of oil has advantages over conventional plant and algal resources as they can be easily grown in bioreactors, have short life cycles, display rapid growth rates, are unaffected by space, light or climatic variations. Fungi are easier to scale up and can be grown on a wide range of inexpensive renewable carbon sources, e.g. lignocellulosic biomass and agro industrial residue (Khot et al., 2012). Major efforts have been made to replace fossil fuels that has had serious environmental issues especially the increased greenhouse effect through the emission of CO2 and NOx gasses that consequently rise global temperature. Combustion of fossil fuels has contributed to the acidification of the oceans that significantly changes marine life.

Biofuels are an attractive alternative as they can be used as transportation fuels with little change to the current technologies (Carere et al., 2008). Liquid transportation biofuels include: bioethanol and biodiesel (Demirbas, 2011). Most vehicles can use from 10 % to 85 % ethanol blends for fuels. Bioethanol is produced by fermentation of corn glucose in the United States or sucrose in Brazil (Rosillo-Calle and Cortez, 1998). The International Energy Agency expects that biofuels will contribute 6 % of total fuel use by 2030.

Recently lipids synthesis by oleaginous fungi from raw cheap materials has received great attention (Venkata Subhash and Venkata Mohan, 2014; Ranjan, 2015). Those produced lipids can be used for biodiesel production (Papanikolaou et al., 2011). Fungal lipids have advantages over algal lipids because fungi are fast growing with short span, light independent and can degrade a wide range of carbon sources (Chen et al., 2012). Lipid production by oleaginous fungi using renewable carbon sources such as: glycerol, sewage water, whey and molasses were reported (Bellou et al., 2012; Peng et al., 2013). Oleaginous microorganisms can convert a wide variety of carbon sources into stored lipids (Ratledge, 2004). Vegetable oils, animal fats and waste cooking oils were traditionally used for biodiesel production (Venkata Subhash and Venkata Mohan, 2014). However, those traditional sources are unsustainable and expensive.

Thraustochytrids are oleaginous microorganisms that can utilize a wide range of substrates including: glucose, galactose, fructose, mannose, sucrose (Yokochi et al., 1998; Shene et al., 2010), complex organic matter (Bongiorni et al., 2005) and cellulosic biomass (Hong et al., 2012), for the production of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs). Thraustochytrids are lipid rich biomass that can be used for biodiesel and PUFA production (Gupta, 2012; Abdel-Wahab et al., 2021a,b, 2022).

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Sampling sites and sample collection

We collected 144 samples from four mangrove sites along the Red Sea and the Arabian Gulf in Saudi Arabia namely: Al-Leith (20° 49′ 10″ N 39° 27′ 26″ E), Jeddah (22° 46′ 32″ N 39° 48′ 25″ E), Syhat (26° 29′ 32″ N 50° 02′ 46″ E) and Yanbu (24°02.55′ N 38°68.89′ E). Collected samples included: 68 decaying leaves of Avicennia marina, 33 decaying thalli of Zostera marina, 14 decaying pneumatophores of A. marina, 9 crab shells, 8 sediment, 7 decaying thalli of Turbinaria ornata and 5 decaying thalli of Cystoseira myrica.

2.2 Isolation of filamentous fungi, yeasts and thraustochytrids

Decaying leaves and pneumatophores of Avicennia marina and decaying thalli of seaweeds were placed in clean plastic bags and brought to the laboratory on the same day. In the laboratory, samples were washed using sterile sea water, cut into small segments (ca 1 cm in length), surface sterilized using 5 % sodium hypochlorite for 1 min, transferred into sterile sea water (1 min), surface dried using sterile filter paper and placed on the surface of GYPTA medium (Abdel-Wahab et al. 2021a). Plates were incubated at 25 °C and examined every 24 h. Microbial growth were transferred to new plates and further purified until axenic cultures were obtained. Pure cultures were maintained on GYP slants (Abdel-Wahab et al. 2021a) and re-subculture every-two months. We also preserved them by cryopreservation at −80 °C and re-subculture every 4 months.

2.3 Sudan Black B test of the isolated microbes

The 84 morphological strains isolated during the present study were tested for their abilities to produce high level of oil using Sudan Black B. Positive strains for oil production were further grown on a larger scale and the percentage of oil were determined using Sulfo-Phospho-Vanlin (SPV) method.

2.4 Quantification of microbial lipids using sulfo-phospho-vanillin (SPV) method

Phosphovanillin (PV) reagent was prepared by dissolving six milligrams of vanillin in 100 mL of hot water and further diluted to 500 mL with phosphoric acid. Oleic and palmitic acids were used as standard and diluted properly with concentrated sulfuric acid to reach 1 mg/mL. Reagents (oleic, palmitic, phosphoric and sulfuric acids and vanillin) were purchased from local company. Twenty-five mg of microbial cells were dissolved in one mL concentrated sulfuric acid, of which 20 µL of the samples were diluted in 180 μL of concentrated sulfuric acid, incubated at 100 °C for 10 min. Samples were cooled to room temperature and 0.5 mL of phosphovanillin reagent was added, incubated at 37 °C for 15 min, cooled to room temperature and stored for 45 min in a dark box for color development. The absorbance was measured at 530 nm in a spectrophotometer (Anschau et al., 2017).

2.5 Lipid extraction and analysis of fatty acids

Biomass and their dry weights were calculated and the lipid was extracted as previously described by Abdel-Wahab et al. (2022). Fatty acids profile of the extracted lipid was determined using methyl esters boron tri-fluoride method (Folch et al., 1957; Abdel-Wahab et al., 2022).

2.6 DNA sequencing and phylogenetic analyses

Pure microbial strains were grown in liquid medium and DNA was extracted using MOBIO microbial DNA extraction kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. ITS region was amplified and sequenced using ITS1 and ITS4 primers. Partial SSU and LSU rDNA were amplified and sequenced using primers pairs NS1/NS4 and LROR/LR7 respectively (Bunyard et al., 1994). PCR amplification and DNA sequencing were carried out by SolGent Inc., South Korea. The obtained sequences were deposited in GenBank (Figs. 2–3, 5). Sequences were aligned using ClustalX (Thompson et al., 1997). Phylogenetic analyses were carried out using MEGA X (Kumar et al., 2018). Bayesian inference was carried out in MrBayes 3.1.2 (Ronquist and Huelsenbeck, 2003). MrModeltest 2.2 was used to determine the best-fit model for the sequences dataset (Nylander, 2004). The phylogenetic tree in Fig. 2 was visualized using Njplot (Perrière and Gouy, 1996) and edited using Adobe Illustrator CS6.

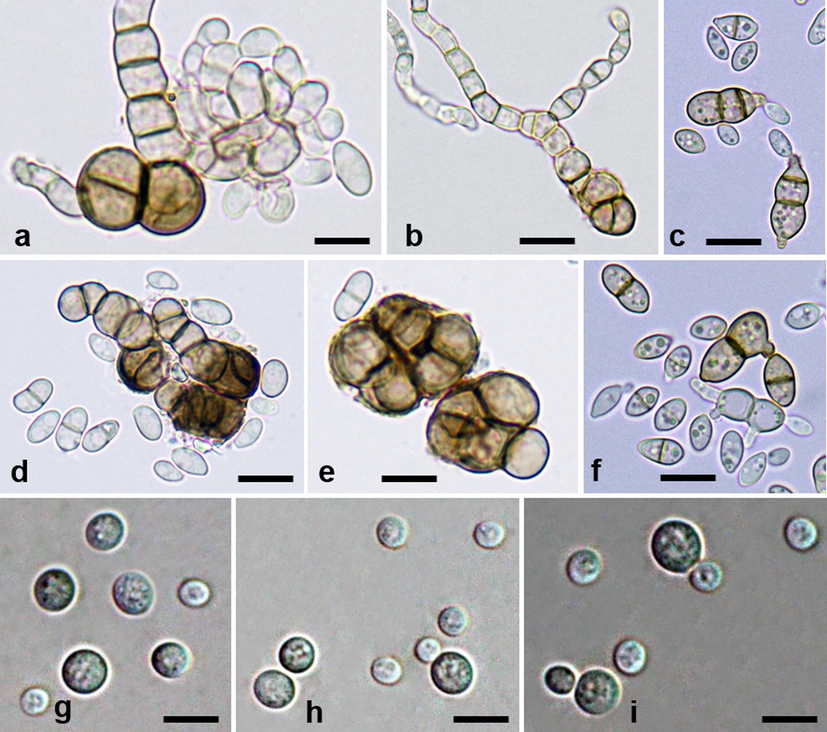

a–f Hortaea werneckii (AL–19) isolated from decaying leaves of Avicennia marina, Al-Leith mangroves, Red Sea. Variously shaped vegetative cells with or without buds and pseudo-hyphae. g–i Rhodotorula mucilaginosa (AL–14) isolated from decaying leaves of Avicennia marina, Al-Leith mangroves, Red Sea. g–i Vegetative cells with or without buds. Bars: a–i = 5 µm.

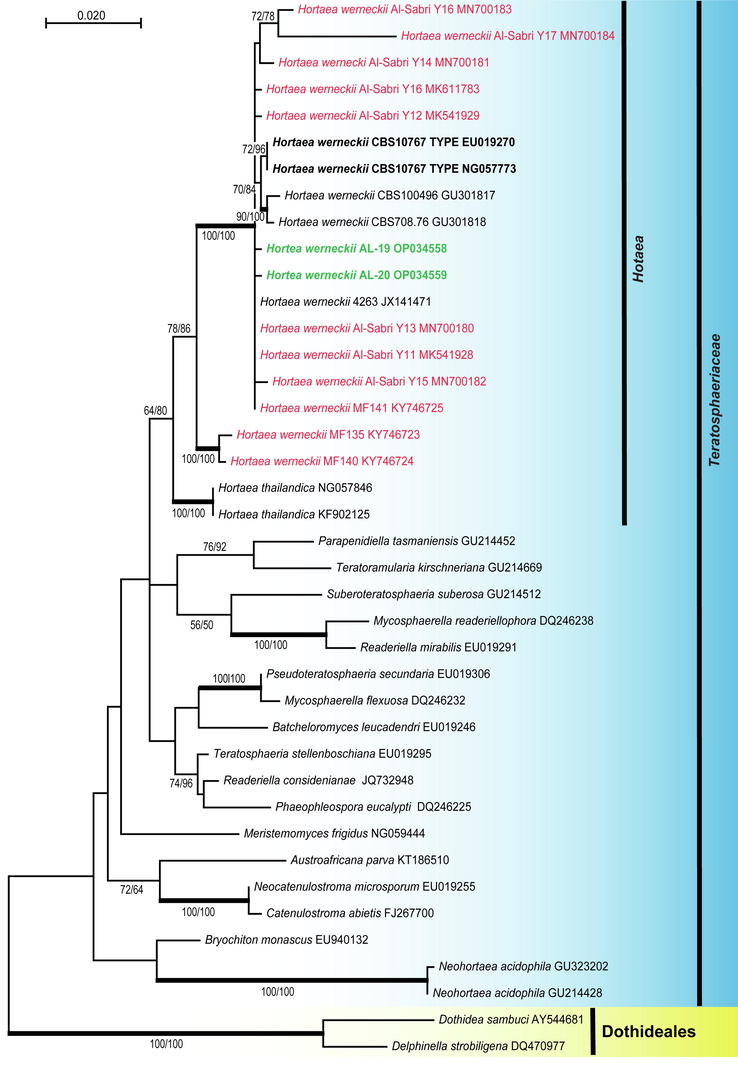

Phylogenetic relationship of Hortaea werneckii strains (AL–19 and AL–20) isolated during the current study. Phylogenetic analyses based on the nucleotide sequences of the LSU rDNA placed the two strains among the other strains of the species. The maximum likelihood (ML) tree (-ln likelihood = 3611.05) was constructed in MEGA X (Kumar et al., 2018). Phylogenetic trees obtained from ML, maximum parsimony (MP) and Bayesian inference posterior probabilities (BYPP) were similar in topology. Bootstrap support on the nodes represents ML and MP ≥ 50 %. Branches with a BYPP of ≥ 95 % are in bold. The two sequences of Hortaea werneckii generated in this study are in green, previous strains of the species from Red Sea are in red.

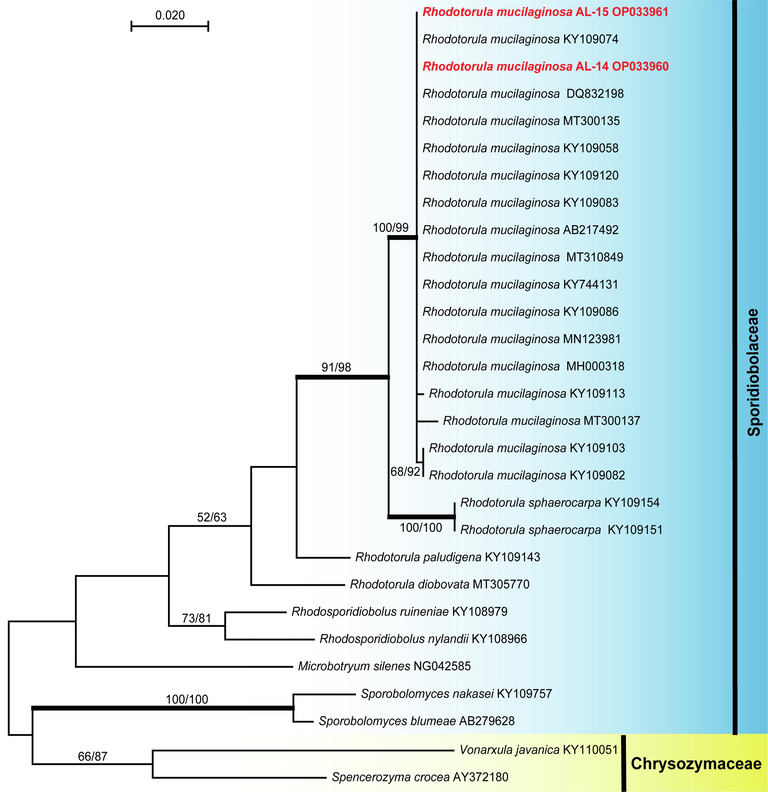

Phylogenetic relationship of Rhodotorula mucilaginosa strains (AL–14 and AL–15) isolated during the current study. Phylogenetic analyses based on the nucleotide sequences of the LSU rDNA placed the two strains among the other strains of the species. The maximum likelihood (ML) tree (-ln likelihood = 2318.03) was constructed in MEGA X (Kumar et al., 2018). The maximum parsimonious data set consisted of 29 taxa include: 18 sequences of Rhodotorula mucilaginosa strains, 4 sequences of other Rhodotorula, 5 sequences of other taxa of Sporidiobolaceae and two taxa belong to Chrysozymaceae (outgroup). Phylogenetic trees obtained from ML, maximum parsimony (MP) and Bayesian inference posterior probabilities (BYPP) were similar in topology. Bootstrap support on the nodes represents ML and MP ≥ 50 %. Branches with a BYPP of ≥ 95 % are in bold. The two sequences of Rhodotorula mucilaginosa generated in this study are in red.

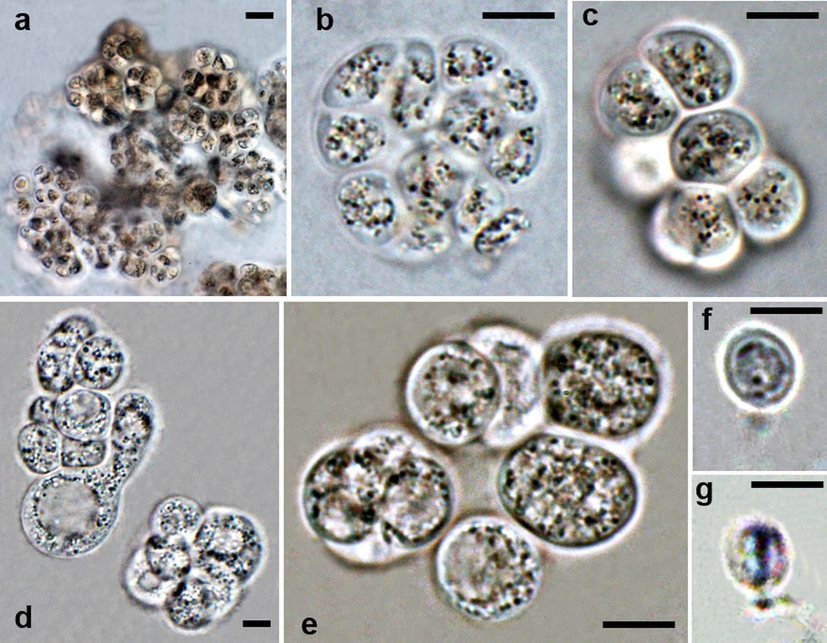

Aurantiochytrium spp. isolated from decaying leaves of Avicennia marina from Syhat mangroves. a–c Aurantiochytrium sp. (SY–78) Variously shaped sporangia. d–g Aurantiochytrium sp. (SY–85). d–e Variously shaped sporangia. f–g Zoospores. Bars: a–g = 5 µm.

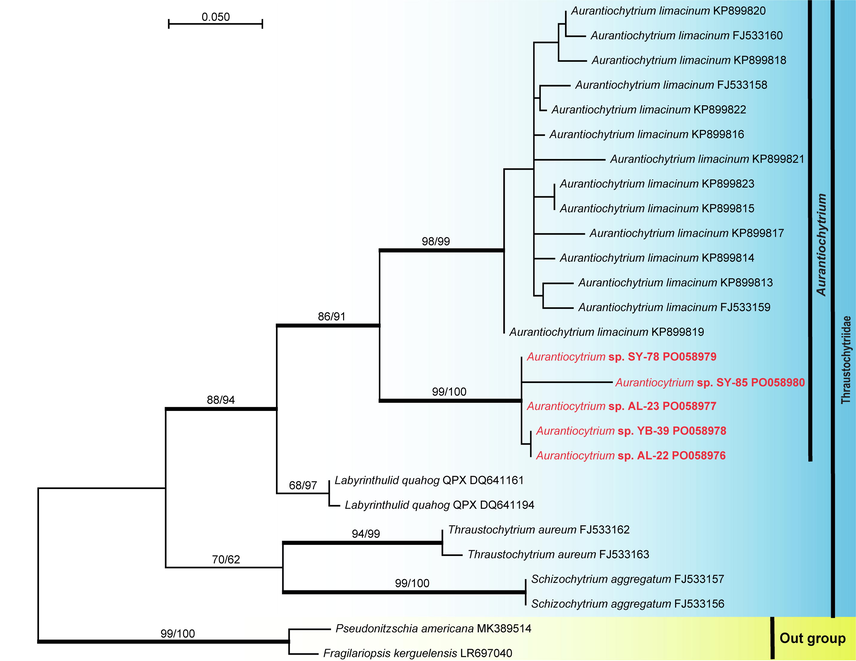

Phylogenetic relationship of oleaginous thraustochytrid strains (AL–22, AL–23, SY–78, SY–85 and YB–39) isolated during the current study from Al-Leith, Syhat and Yanbu mangroves. Phylogenetic analyses based on the nucleotide sequences of the ITS region placed the five strains in a well-supported node basal to other strains of the genus Aurantiochytrium. The maximum likelihood (ML) tree (-ln likelihood = 1185.76) was constructed in MEGA X (Kumar et al., 2018). Phylogenetic trees obtained from ML, maximum parsimony (MP) and Bayesian inference posterior probabilities (BYPP) were similar in topology. Bootstrap support on the nodes represents ML and MP ≥ 50 %. Branches with a BYPP of ≥ 95 % are in bold. The newly generated sequences in this study are in red.

Bayesian inference.

3 Results

3.1 Diversity of oleaginous filamentous fungi and yeasts from Saudi mangroves

A total of 961 isolates (include 759 filamentous fungi and 202 yeasts) were isolated from 144 submerged marine samples that include: 68 decaying leaves of Avicennia marina, 33 decaying thalli of Zostera marina, 14 decaying pneumatophores of Avicennia marina, 9 crab shells, 8 sediment, 7 decaying thalli of Turbinaria ornata and 5 decaying thalli of Cystoseira myrica. Samples were collected from four mangrove sites: Al-Leith, Jeddah and Yanbu (Red Sea) and Syhat (Arabian Gulf). Isolated fungi were grouped into 62 morphological types that include: 21 yeasts and 41 filamentous fungi. Aspergillus and Penicillium species were the most common fungi and represented by 337 and 330 isolates respectively. Other recorded genera were: Cladosporium, Lasiodiplodia, Mortierella and Rhizopus. Forty-three isolates did not fruit in culture and were grouped into ten morphological types (Table 1).

Strain No.

Microorganism name

No. of isolates

Substrate

Dry weight (g/L)

Lipid (% w/w)

#AL-14

Rhodotorula mucilaginosa (A. Jörg.) F.C. Harrison

4

Decaying thallus of Padina pavonica

36.2

35.2

#AL-15

R. mucilaginosa

4

Decaying thallus of Zostera marina

34.9

30.1

AL-16

Yeast

2

Decaying thallus of Sargassum

AL-17

Yeast

2

Decaying thallus of Sargassum platycarpum

AL-18

Yeast

1

Decaying thallus of Sargassum platycarpum

#AL-19

Hortaea werneckii (Horta) Nishim. & Miyaji

10

Decaying leaves of Avicennia marina

42

46.2

#AL-20

H. werneckii

2

Decaying leaves of Avicennia marina

44.9

45

JD-11

Yeast

5

Decaying leaves of Avicennia marina

JD-12

Yeast

5

Decaying leaves of Avicennia marina

JD-13

Yeast

9

Decaying leaves of Avicennia marina

JD-14

Sterile mycelium

7

Decaying leaves of Avicennia marina

JD-15

Yeast

37

Decaying leaves of Avicennia marina

JD-16

Aspergillus sp.

67

Decaying leaves of Avicennia marina

JD-17

Yeast

5

Decaying thallus of Zostera marina

JD-18

Aspergillus flavus Link

8

Decaying thallus of Zostera marina

JD-19

Yeast

10

Decaying thallus of Zostera marina

JD-20

Yeast

23

Decaying leaves of Avicennia marina

JD-21

Penicillium citrinum Thom

15

Decaying leaves of Avicennia marina

JD-22

Yeast

10

Decaying leaves of Avicennia marina

JD-23

Yeast

12

Decaying leaves of Avicennia marina

JD-24

Yeast

22

Decaying leaves of Avicennia marina

JD-25

Sterile mycelium

9

Decaying leaves of Avicennia marina

42.7

19.25

JD-26

Yeast

11

Decaying leaves of Avicennia marina

JD-27

Yeast

10

Decaying leaves of Avicennia marina

JD-28

Sterile mycelium

8

Decaying leaves of Avicennia marina

JD-29

Cladosporium sp.

12

Decaying thallus of Zostera marina

JD-30

Yeast

11

Decaying leaves of Avicennia marina

JD-31

Penicillium sp.

6

Decaying leaves of Avicennia marina

JD-32

Aspergillus terreus Thom

147

Sediment

JD-33

Rhizopus sp.

2

Sediment

18.9

JD-34

Mortierella sp.

6

Decaying leaves of Avicennia marina

JD-35

Sterile mycelium

5

Decaying thallus of Sargassum platycarpum

JD-36

Mortierella sp.

8

Sediment

23.1

JD-37

Aspergillus sp.

21

Sediment

JD-38

Aspergillus sp.

10

Decaying thallus of Sargassum platycarpum

JD-39

Penicillium sp.

12

Decaying leaves of Avicennia marina

#SY-69

Lasiodiplodia theobromae (Pat.) Griffon & Maubl.

3

Decaying leaves of Avicennia marina

48.2

34.1

#SY-70

Aspergillus sp.

7

Decaying leaves of Avicennia marina

43.1

48.23

SY-71

Rhizopus sp.

4

Decaying leaves of Avicennia marina

62.3

50.85

SY-72

Sterile mycelium

1

Decaying leaves of Avicennia marina

SY-73

Sterile mycelium

1

Decaying wood of Avicennia marina

SY-74

Penicillium sp.

3

Decaying leaves of Avicennia marina

SY-75

Sterile mycelium

4

Decaying leaves of Zostera marina

SY-76

Sterile mycelium

1

Decaying leaves of Avicennia marina

YB-21

Yeast

7

Decaying leaves of Avicennia marina

YB-22

Penicillium sp.

15

Decaying leaves of Avicennia marina

YB-23

Sterile mycelium

2

Sediment

YB-24

Penicillium sp.

15

Decaying thallus of Zostera marina

YB-25

Penicillium sp.

21

Decaying thallus of Turbinaria ornata

YB-26

Aspergillus sp.

6

Decaying thallus of Cystoseira myrica

21.6

YB-27

Penicillium sp.

10

Decaying leaves of Avicennia marina

YB-28

Penicillium sp.

9

Decaying leaves of Avicennia marina

YB-29

Aspergillus sp.

13

Decaying thallus of Zostera marina

YB-30

Aspergillus sp.

30

Sediment

YB-31

Aspergillus sp.

25

Decaying pneumatophores of Avicennia marina

16.4

26.86

YB-32

Penicillium sp.

35

Decaying leaves of Avicennia marina

YB-33

Penicillium sp.

55

Crab shell

16.3

30.54

YB-34

Penicillium sp.

60

Sediment

YB-35

Penicillium sp.

55

Sediment

YB-36

Aspergillus niger Tiegh.

16

Decaying leaves of Avicennia marina

YB-37

Sterile mycelium

5

Decaying leaves of Avicennia marina

7.1

YB-38

Penicillium sp.

20

Decaying leaves of Avicennia marina

21.3

AL: Al-Leith mangroves, Al-Leith City, Re Sea, Saudi Arabia.

JD: Jeddah mangroves, Jeddah City, Red Sea, Saudi Arabia.

SY: Syhat mangroves, Dammam city, Arabian Gulf, Saudi Arabia.

YB: Yanbu mangroves, Yanbu City, Red Sea, Saudi Arabia.

#Supported by molecular data.

Studied strains in bold.

The 202 isolates of yeasts were cultured from 48 samples of decaying leaves of Avicennia marina and seaweeds. The yeast isolates were grouped into 21 morphological types, of which four morphological types were identified using molecular phylogenetics of ribosomal genes.

3.2 Diversity of oleaginous thraustochytrids from the Saudi mangroves

Fifty-four isolates of thraustochytrids were cultured from the four mangrove sites namely: Al-Leith, Jeddah and Yanbu (Red Sea) and Syhat (Arabian Gulf). Isolated thraustochytrids were grouped into 22 strains. Isolated thraustochytrids belonged to two genera: Aurantiochytrium and Thraustochytrium (Table 2). Thraustochytrids that produced high biomass and high levels of lipid were chosen for further study. Selected strains were grown on a larger volume of culture media and their lipid were extracted and the fatty acids and their derivatives were determined using GC/MS. AL: Al-Leith mangroves, Al-Leith City, Re Sea, Saudi Arabia. JD: Jeddah mangroves, Jeddah City, Red Sea, Saudi Arabia. SY: Syhat mangroves, Dammam city, Arabian Gulf, Saudi Arabia. YB: Yanbu mangroves, Yanbu City, Red Sea, Saudi Arabia. #Supported by molecular data. Studied strains in bold.

Strain No.

Microorganism name

No. of isolates

Substrate

Dry weight (g/L)

Lipid (% w/w)

AL-21

Aurantiochytrium sp.

3

Decaying leaves of A. marina

#AL-22

Aurantiochytrium sp.

2

Decaying leaves of A. marina

46

62

#AL-23

Aurantiochytrium sp.

4

Decaying leaves of A. marina

32

44.8

AL-24

Thraustochytrium sp.

1

Decaying leaves of A. marina

AL-25

Thraustochytrium sp.

2

Decaying leaves of A. marina

AL-26

Aurantiochytrium sp.

2

Decaying leaves of A. marina

50.1

66.5

AL-27

Aurantiochytrium sp.

7

Decaying leaves of A. marina

43

52

AL-28

Aurantiochytrium sp.

1

Decaying leaves of A. marina

38

54.1

AL-29

Aurantiochytrium sp.

1

Decaying leaves of A. marina

43

57

AL-30

Aurantiochytrium sp.

4

Decaying leaves of A. marina

JD-40

Aurantiochytrium sp.

6

Decaying leaves of A. marina

48.2

71.42

SY-77

Aurantiochytrium sp.

1

Decaying leaves of A. marina

16.1

38.3

#SY-78

Aurantiochytrium sp.

3

Decaying leaves of A. marina

32

44

SY-79

Aurantiochytrium sp.

1

Decaying leaves of A. marina

26.6

47.2

SY-80

Aurantiochytrium sp.

1

Decaying leaves of A. marina

21.8

39

SY-81

Aurantiochytrium sp.

3

Decaying leaves of A. marina

28

49

SY-82

Aurantiochytrium sp.

1

Decaying leaves of A. marina

13.4

36

SY-83

Aurantiochytrium sp.

4

Decaying leaves of A. marina

SY-84

Aurantiochytrium sp.

2

Decaying leaves of A. marina

28.9

46.1

#SY-85

Aurantiochytrium sp.

1

Decaying thalli of Zostera marina

49.3

59.9

#YB-39

Aurantiochytrium sp.

3

Decaying leaves of A. marina

49.9

64.96

YB-40

Aurantiochytrium sp.

1

Decaying leaves of A. marina

52.8

60.39

3.3 Molecular phylogenetics of yeasts and thraustochytrids

Four oleaginous yeast strains were selected and their taxonomical placements were determined based on LSU rDNA and ITS and were placed in Rhodotorula mucilaginosa and Hortaea werneckii (Table 1, Figs. 1–3). DNA was extracted from the most promising thraustochytrid isolates and their taxonomical placements were determined based on ITS sequences. Thraustochytrids from the Arabian Gulf and the Red Sea formed a separate node basal to other known Aurantiochytrium species and might represent undescribed taxa (Figs. 4-5).

3.4 Lipid profile of yeasts and thraustochytrid strains

Two oleaginous yeasts: Hortaea werneckii (Horta) Nishim. & Miyaji (AL–19) and Rhodotorula mucilaginosa (A. Jörg.) F.C. Harrison (AL–14) and four Aurantiochytrium strains: AL–22, AL–23, SY–78 and SY–85 produced high dry weight ranged between 32 and 49.3 g/L of which 35.2–62 % lipid. These promising results can be improved by changing the growth conditions using different combinations of different C/N ratio. Fatty acid profiles of the six strains on GC/MS were determined. Palmitic acid was the major fatty acid in the lipid of the four thraustochytrid isolates and ranged between 5.71 and 82 % of the total fatty acids, while it was not recorded from the lipid of the two yeast isolates, 9-Octadecenamide, (Z)- was the major fatty acid amide in the lipid of the two isolates and two thraustochytid isolates and ranged between 26.94 and 56.63 %, followed by 13-Docosenamide, (Z)- (20.44–34.99 %) from the same four isolates. Other major lipid compounds were: Hexadecanamide (4.35–7.19 %), Cholestrol (7.24–15.07 %), Butylated Hydroxytoluene (3.46–15.76 %), Octadecanamide (3.95–7.9 %), Phenol, 2-(1,1-dimethylethyl)-5-methyl- (1.78–10.33 %) and Pentadecanoic acid (7.47 %) (Tables 3).

Microbes/fatty acids (%)

Hortaea werneckii (AL-19)

Rhodotorula mucilaginosa (AL-14)

Aurantiochytrium sp. (AL-22)

Aurantiochytrium sp. (AL-23)

Aurantiochytrium sp. (SY-78)

Aurantiochytrium sp. (SY-85)

Palmitic acid (C16H32O2)

–

–

5.71

7.52

71.92

82.02

9-Octadecenamide, (Z)- (C18H35NO)

49.68

56.63

37.73

26.94

–

–

13-Docosenamide, (Z)- (C22H43NO)

27.87

34.99

24.32

20.44

–

–

Hexadecanamide (C16H33NO)

7.06

7.19

6.51

4.35

–

–

Cholesterol (C27H46O)

–

–

7.24

15.07

–

–

Butylated Hydroxytoluene (C15H24O)

–

–

–

–

15.76

3.46

Octadecanamide (C18H37NO)

7.9

–

4.08

3.95

–

–

Phenol, 2-(1,1-dimethylethyl)-5-methyl- (C11H16O)

–

–

–

–

1.78

10.33

Pentadecanoic acid (C15H30O2)

–

–

7.47

–

–

–

Stigmasterol (C29H48O)

–

–

2.23

4.36

–

–

1-Heptatriacotanol (C37H76O)

1.33

1.19

–

3.09

–

–

Methyl tetradecanoate (C15H30O2)

–

–

–

–

4.41

–

4 Discussion

Palmitic acid was the major fatty acid in the four studied strains of thraustochytrids and ranged between 5.71 and 82.02 % of the total fatty acids. Ramos et al. (2009) reported high amount of palmitic acid from Aurantiochytrium species. Palmitic acid reported from thraustochytrids has high octane number, low iodine content and high oxidation stability and can be used to produce high quality biodiesel. Genera of thraustochytrids were reported to accumulate commercially and biologically important fatty acids (Chang et al., 2014). The major fatty acids of thraustochytrids are palmitic acid C16, arachidonic acid C20:4, eicosapentaenoic acid C20:5, docosapentaenoic acid C22:5, and docosahexaenoic acid C22:6 (DHA) (Kobayashi et al., 2011). Among these fatty acids, palmitic acid has been reported to be potential alternative materials for microbial-derived biodiesel (Kobayashi et al., 2011). Velmurugan et al. (2021) studied the fatty acids composition of two strains of Aurantiochytrium cultured from Taiwan mangroves. Major fatty acids reported were the saturated acids: pentadecanoic (15:0), palmitic (C16:0), and unsaturated DHA (C22:6) which is consistent with previous results (Jaritkhuan and Suanjit, 2018). Bai et al. (2022) isolated 58 thraustochytrid strains isolated from the coastal waters of Qingdao, China and studied their fatty acid profile. Isolated strains were phylogenetically affiliated with the genera: Botryochytrium, Oblongichytrium, Schizochytrium, Thraustochytrium, and Sicyoidochytrium. Palmitic acid was the most abundant fatty acid in the studied 58 strains and represented 7.90–37.12 % of the total fatty acids.

Oleaginous yeast and thraustochytrid strains produced 9-Octadecenamide, (Z)- as the major fatty acid derivative (ranged between 26.94 and 56.63 % of the total fatty acids). 9-Octadecenamide, (Z)- (Oleamide) is the amid of Oleic acid and was first detected in human plasma and was shown to induce sleep in animals (Mckinney and Cravatt, 2005). Oleamide can be used for the treatment of mood and sleep disorders (Mechoulam et al., 1997). The third major fatty acid derivative was 13-Docosenamide, (Z)- (ranged between 20.44 and 34.99 % of the total fatty acids) and recorded from both yeasts and thraustochytrids. 13-Docosenamide is the amide of docosenoic acid (Erucic acid) and it was first identified from cerebrospinal fluid of sleep-deprived cats and from cerebrospinal fluid of rats and humans. 13-Docosenamide causes reduced mobility and slightly lessened awareness in rats (Li et al., 2017). Both 9-Octadecenamide, (Z)- and 13-Docosenamide, (Z)- have antimicrobial and anticancer activities (Sharma et al., 2019).

5 Conclusion

In this study we isolated 84 morphological strains (21 yeasts, 41 filamentous fungi and 22 thraustochytrids) from the four studied mangrove sites and were screened for their abilities to produce high level of lipids using Sudan Black B. Positive strains for oil production were further grown on a larger scale and the percentage of oil were determined using Sulfo-Phospho-Vanlin (SPV) method. Two oleaginous yeasts: Hortaea werneckii and Rhodotorula mucilaginosa and four Aurantiochytrium strains produced high dry weight ranged between 32 and 49.3 g/L of which 35.2–62 % lipid and their fatty acid profile were determined using GC/MS. Palmitic acid was the major fatty acid in the lipid of the four thraustochytrid isolates and ranged between 5.71 and 82 % of the total fatty acids, 9-Octadecenamide, (Z)- was the major fatty acid amide in the lipid of the two yeast isolates and two thraustochytid isolates and ranged between 26.94 and 56.63 %, followed by 13-Docosenamide, (Z)- (20.44–34.99 %) from the same four isolates. Other major lipid compounds were: Hexadecanamide, Cholestrol, Butylated Hydroxytoluene, Octadecanamide, Phenol, 2-(1,1-dimethylethyl)-5-methyl and Pentadecanoic acid.

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by the National Plan for Science, Technology and Innovation (MAARIFAH), King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Award No. 2-17-01-001-0049.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Fatty acid production of thraustochytrids from Saudi Arabian mangroves. Saudi J. Biol. Sci.. 2021;28:855-864.

- [Google Scholar]

- Thraustochytrids from the Red Sea mangroves in Saudi Arabia and their abilities to produce docosahexaenoic acid. Bot. Mar.. 2021;64:489-501.

- [Google Scholar]

- Utilization of low-cost substrates for the production of high biomass, lipid and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) using local native strain Aurantiochytrium sp. YB-05. J. King Saud Uni. Sci.. 2022;34:102224

- [Google Scholar]

- Validation of the sulfo-phosphovanillin (spv) method for the determination of lipid content in oleaginous microorganisms. Braz. J. Chem. Eng.. 2017;34:19-27.

- [Google Scholar]

- Culturable diversity of thraustochytrids from coastal waters of Qingdao and their fatty acids. Mar. Drugs. 2022;20:229.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lipids containing polyunsaturated fatty acids synthesized by zygomycetes grown on glycerol. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol.. 2012;166:146-158.

- [Google Scholar]

- Enzymatic activities of epiphytic and benthic thraustochytrids involved in organic matter degradation. Aquat. Microb. Ecol.. 2005;41:299-305.

- [Google Scholar]

- A systematic assessment of Morchella using RFLP analysis of the 28S rRNA gene. Mycologia. 1994;86:762-772.

- [Google Scholar]

- Third generation biofuels via direct cellulose fermentation. Int. J. Mol. Sci.. 2008;9:1342-1360.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of Thraustochytrids Aurantiochytrium sp., Schizochytrium sp., Thraustochytrids sp., and Ulkenia sp. for production of biodiesel, long-chain omega-3 oils, and exopolysaccharide. Mar. Biotechnol.. 2014;16:396-411.

- [Google Scholar]

- Oil production on wastewaters after butanol fermentation by oleaginous yeast Trichosporon coremiiforme. Bioresour. Technol.. 2012;118:594-597.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biofuels from algae for sustainable development. Applied. Energy. 2011;88:3473-3480.

- [Google Scholar]

- A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipids from animal tissues. J. Biol. Chem.. 1957;226:497-509.

- [Google Scholar]

- Omega-3 biotechnology: thraustochytrids as a novel source of omega-3 oils. Biotechnol. Adv.. 2012;30:1733-1745.

- [Google Scholar]

- Growth of the oleaginous microalga Aurantiochytrium sp. KRS101 on cellulosic biomass and the production of lipids containing high levels of docosahexaenoic acid. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng.. 2012;35:129-133.

- [Google Scholar]

- Species diversity and polyunsaturated fatty acid content of thraustochytrids from fallen mangrove leaves in Chon Buri Province. Thailand. Agric. Nat. Resour.. 2018;52:24-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- Single cell oil of oleaginous fungi from the tropical mangrove wetlands as a potential feedstock for biodiesel. Microb. Cell Fact.. 2012;11:71.

- [Google Scholar]

- Increase of eicosapentaenoic acid in thraustochytrids through thraustochytrid ubiquitin promoter-driven expression of a fatty acid D5 desaturase gene. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.. 2011;77:3870-3876.

- [Google Scholar]

- MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol.. 2018;35:1547-1549.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antidepressant and anxiolytic-like behavioral effects of erucamide, a bioactive fatty acid amide, involving the hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal axis in mice. Neurosci. Lett.. 2017;640:6-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Structure and Function of Fatty Acid Amide Hydrolase. Annu. Rev. Biochem.. 2005;74:411-432.

- [Google Scholar]

- MrModeltest 2.2. Program distributed by the author. Evolutionary Biology Centre, Uppsala University; 2004.

- Biotechnological conversion of waste cooking olive oil into lipid-rich biomass using Aspergillus and Penicillium strains. J. Appl. Mirobiol.. 2011;110:1138-1150.

- [Google Scholar]

- Microbial conversion of wastewater from butanol fermentation to microbial oil by oleaginous yeast Trichosporon dermatis. Ren. Energy. 2013;55:31-34.

- [Google Scholar]

- WWW-query: an on-line retrieval system for biological sequence banks. Biochimie. 1996;78:364-369.

- [Google Scholar]

- Influence of fatty acid composition of raw materials on biodiesel properties. Bioresour. Technol.. 2009;100:261-268.

- [Google Scholar]

- Endophytic fungi: prospects in biofuel production. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. India Sect. B. Biol. Sci.. 2015;85:21-25.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fatty acid biosynthesis in microorganisms being used for single cell oil production. Biochimie. 2004;86:807-815.

- [Google Scholar]

- MRBAYES 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1572-1574.

- [Google Scholar]

- Towards proalcohol II: a review of the Brazilian bioethanol programme. Biomass Bioenergy. 1998;14:115-124.

- [Google Scholar]

- An Update on Bioactive Natural Products from Endophytic Fungi of Medicinal Plants. In: Arora D., Sharma C., Jaglan S., Lichtfouse E., eds. Pharmaceuticals From Microbes. Springer; 2019. p. :121-154.

- [Google Scholar]

- Microbial oils and fatty acids: effect of carbon source on docosahexaenoic acid (c22:6 n-3, DHA) production by thraustochytrid strains. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr.. 2010;10:207-216.

- [Google Scholar]

- The ClustalX windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucl. Acids Res.. 1997;25:4876-4882.

- [Google Scholar]

- Characterization of cellular development and fatty acid accumulation in thraustochytrid Aurantiochytrium strains of Taiwan. Bot. Mar.. 2021;64:477-487.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lipid accumulation for biodiesel production by oleaginous fungus. Fuel. 2014;116:509-515.

- [Google Scholar]

- Optimization of docosahexaenoic acid production by Schizochytrium limacinum SR21. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol.. 1998;49:72-76.

- [Google Scholar]

Appendix A

Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2023.102615.

Appendix A

Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article: