Translate this page into:

Semen characteristics of fertile and subfertile men in a fertility clinic and correlation with age

*Tel./fax: +966 14786031 naleisa@ksu.edu.sa (Nadia A.S. Aleisa)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Available online 28 June 2012

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Background

The characteristics and semen quality in the men of different populations have been reported, though such data are lacking in Saudis.

Objectives

(i) To characterize the semen parameters of fertile and subfertile men, (ii) To study the prevalence of abnormality of semen parameters in the subfertile group, and (iii) To identify the relationship between semen parameters and age.

Methods

This study included 49 fertile and 160 subfertile men and 76 men with unproven fertility attending a fertility clinic in Riyadh. Their semen parameters were estimated, statistically analyzed, characterized, and correlation studies were conducted.

Results

The median age of the fertile and subfertile groups was quite similar. Significant differences were demonstrated in the median values of sperm concentration (98.6 × 106/ml vs 14.5 × 106/ml, P < 0.001), progressive sperm motility (58% vs 40%, P< 0.001), and abnormal sperm morphology (55% vs 75%, P< 0.001) between fertile and subfertile men. The percentage of normal semen viscosity was higher in fertile men, whereas the median semen volume values were nearly similar in the fertile and subfertile men (2.5 vs 2.75 ml). The prevalence of asthenozoospermia (36%) and azoospermia (26%) among subfertile men was the highest among other semen abnormality categories. There was an inverse correlation between the age and both sperm motility and semen volume in the investigated groups.

Conclusion

The main semen parameters in the fertile and subfertile subjects in this study differ significantly and the age was demonstrated to be correlated inversely with sperm motility and semen volume. Further studies in other regions of Saudi Arabia are needed.

Keywords

Age

Asthenozoospermia

Azoospermia

Male infertility

Saudi population

Semen

Spermatozoa

1 Introduction

Semen quality is one of the most valuable indications of male reproductive health where semen analysis plays a critical role in the diagnosis and treatment of male infertility. Semen analysis is widely undertaken applying the reference values for normal semen measurements published by the World Health Organization (WHO, 1999).

Several studies during the last decades have highlighted the concern of a time-related decrease in the semen quality worldwide (Miyamoto et al., 2012). They provided the evidences of a decreasing trend in sperm count and percentage of sperm motility or normal sperm morphology over the last decades, from France (Auger et al., 1995), Scotland (Irvine et al., 1996), Italy (Bilotta et al., 1999), Denmark (Andersen et al., 2000; Jensen et al., 2002), India (Adiga et al., 2008), and Tunisia (Feki et al., 2009).

These findings are of an important concern since men with sperm count <40 × 106/ml were indicated to experience reduced fecundity (Bonde et al., 1998). However, in contradiction, other studies reported nonsignificant change in human semen quality (Bujan et al., 1996; Fisch et al., 1996; Rasmussen et al., 1997; Andolz et al., 1999; Acacio et al., 2000; Swan et al., 2000; Marimuthu et al., 2003; Axelsson et al., 2011). Hence, the global temporal trend in semen quality is still on debate.

Regional differences in semen quality have been reported for some areas in the USA (Fisch et al., 1996), Europe (Jørgensen et al., 2001; Jørgensen et al., 2002), Japan (Iwamoto et al., 2006), India (Adiga et al., 2008), and China (Gao et al., 2007). The European study of fertile men showed that sperm concentration of Danish men was 74% of that of Finnish men and 82% of the Scottish men (Jørgensen et al., 2001). In Southwest China, Li et al. (2009) showed that the semen parameters’ values of men were markedly different from those reported for the other Chinese, USA or Europeans. Japanese fertile men had a semen quality level similar to Danish men that reported to have the lowest values among the investigated men in Europe (Iwamoto et al., 2006).

Nevertheless, some studies suggested that a decline in semen parameters is associated with increased age (Kidd et al., 2001; Chen et al., 2003; Eskenazi et al., 2003; Maya et al., 2009).

However, others showed no such association (Chen et al., 2004; Seo et al., 2000; Li et al., 2009).

In Saudi Arabia, the WHO reference values have been used to assess the reproductive health of Saudi men and there are no available data for the semen parameters in different cities, neither in other Arabic countries, except those reported for subfertile Tunisian men by Feki et al. (2009).

This study aimed to evaluate the semen characteristics of Saudi fertile, subfertile men, and men of unproven fertility in a fertility clinic in Riyadh city and to investigate the relationship between age and semen parameters.

2 Methods

2.1 Subjects

The study samples were male partners from couples attending a fertility clinic in Riyadh city, including 49 fertile, 160 subfertile men, and 76 men with unproven fertility. Fertile men included individuals of proven fertility whose wives achieved a full term pregnancy within the last two years. Subfertile men were men whose female partners failed to conceive but had no diagnosed fertility disorder after one year of unprotected intercourse. Men of unproven fertility were those visiting the clinic for reasons other than the fertility issue.

Each individual completed an extensive questionnaire regarding age, social status, occupation, and the reproductive history. As the occupations of most of the participants were either military or office jobs, the study population was grouped according to occupation, and categorized as civilian and military.

2.2 Semen collection and analysis

Semen samples were collected by masturbation after 3–5 days of sexual abstinence in clean metal-free plastic containers. After liquefaction, an aliquot of semen was centrifuged at 1400g for 10 min. Subsequently, semen analysis was carried out according to WHO guidelines (1999) including liquefaction time, pH, odor, volume, viscosity, the presence of pus/epithelial cells, sperm motility, sperm concentration, and abnormal morphology. Sperm motility was assessed as either motile (WHO motility classes A + B + C) or immotile (class D).

Semen findings in subfertile men were categorized as normal (normal semen values according to WHO standards); azoospermia (no spermatozoa in the ejaculate); oligozoospermia (sperm concentration <20 × 106/ml); asthenzoospermia (<50% motile sperm); oligoasthenozoospermia (including both criteria).

2.3 Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed by using statistical software package (SAS) version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute Inc. Cary, NC, USA). Because semen parameters follow markedly skewed (non-normal) distributions, the 25th–75th percentiles, medians, means and standard deviations were calculated. The data in the different groups were compared by Mann–Whitney, a non-parametric test, or the Chi-square test as appropriate. Logarithmic transformation of the age and the semen volume of fertile group and square root transformation of age and sperm concentration of fertile group yielded normal distributions, therefore Pearson’s correlation coefficient was calculated. In contrast, no suitable transformations for the other variable groups yield normal distributions; hence Spearman’s correlation coefficient was calculated to correlate age and semen parameters. Only the semen parameters that significantly correlated were plotted versus age for the pooled data and the different status along with the regression line. ANOVA test was used to determine mean differences according to occupation. Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

3 Results

3.1 Social parameters

There was nonsignificant difference either in the median age (37 and 34 years) or in the duration of marriage (10 and 6 years) in fertile or subfertile groups, respectively. Chi-Square test showed nonsignificant difference in the percentage of each of the occupation categories (civilian and military personnel) between the fertile and subfertile groups (civilian: 73.5% and 75.3%; militaries: 26.5% and 24.7%, respectively) (Table 1). n = number of the subjects; S.D. = standard deviation (25–75) = 25th–75th percentile. The difference between fertile and subfertile groups is significant at ∗P ⩽ 0.05 or ∗∗P ⩽ 0.001.

Pooled data

Fertile

Subfertile

Unproven fertility

n

(Mean ± S.D.)

Median (25–75)

n

(Mean ± S.D.)

Median (25–75)

n

(Mean ± S.D.)

Median (25–75)

n

(Mean ± S.D.)

Median (25–75)

Age(years)

285

33.79 ± 8.257

32(28–39)

49

37 ± 7.056

37(31.5–40.5)

160

35.65 ± 8.67

34(29–40)

76

27.81 ± 4.05

27(25–30)

Duration of unprotected intercourse (years)

207

9.83 ± 8.03

7(3–15)

48

10.89 ± 7.06

10(4.25–15)

159

9.509 ± 8.3

6(3–13)

–

–

–

Semen volume (ml)

283

3.122 ± 1.69

3(2–4)

49

3.03 ± 1.61

2.5(1.75–4.125)

158

2.94 ± 1.6

2.75(2–4)

76

3.56 ± 1.87

3(2.5–4.5)

Sperm Concentration (106/ml)

283

60.48 ± 63.42

48.6(5–93)

49

116.40 ± 57.97

98.6∗∗(80–151.5)

158

39.38 ± 49.54

14.5∗∗(1–75)

76

68.28 ± 69.22

55.5(11.95–91.75)

Sperm motility (%)

234

45.01 ± 20.54

46(30.75–59)

49

57.43 ± 15.97

58∗∗(49–67.5)

118

39 ± 19.8

40∗∗(25–50)

67

46.64 ± 20.61

48(30–60)

Sperm abnormal morphology (%)

221

65.56 ± 16.54

65 (55–80)

49

55.20 ± 12.78

55∗∗(45–65)

107

71.74 ± 15.66

75∗∗(60–85)

65

63.18 ± 16.14

65(50–77.5)

Semen viscosity:

Normal

283

246 (86.9%)

49

46 (93.88%)

158

133 (84.2%)

76

67 (88.16%)

Increase

24 (8.5%)

2 (4.1%)

17 (10.76%)

5 (6.69%)

Highincrease

13 (4.6%)

1 (2.05%)

8 (5.06%)

4 (5.26%)

Occupation:

Civilian

278

207 (74.5%)

49

36 (73.5%)

154

116 (75.3%)

75

55 (73.33%)

Military

71 (25.5%)

13 (26.5%)

38 (24.7%)

20 (26.7%)

3.2 Sperm characteristics

There was a significant difference in the median values of sperm concentration, sperm motility, and sperm abnormal morphology between the fertile and subfertile men. Sperm concentration and sperm motility were higher in the fertile, while abnormalities were more frequent in the subfertile group.

Semen volume, showed nonsignificant difference between the two groups although the percentage of men with normal viscosity was higher in the fertile than in the subfertile men, and the percentage of men with increased viscosity was higher in subfertile men.

3.3 Sperm quality of subfertile men

11.4% of the subfertile group had sperm concentration and sperm motility within normal range being nonsignificantly different from that of the fertile men. Interestingly, the prevalence of asthenozoospermia (35.5%) and azoospermia (26%) were the highest among other categories of subfertile group (Table 2). The difference between fertile and subfertile groups is significant at ∗P ⩽ 0.05 or ∗∗P ⩽ 0.001. (25–75) = 25th–75th percentile.

Semen quality

n (%)

Sperm concentration (106/ml)

Sperm motility

Mean ± S.D.

Median (25–75)

Mean ± S.D.

Median (25–75)

Fertile

49

116.40 ± 57.97

98.6(80–151.5)

57.43 ± 15.8

58(49–67.5)

Subfertile

158

Normala

18 (11.4%)

99.27 ± 39.8

97.1(79.95–116.5)

66 ± 11.2

65(55–75.25)

Azoospermia

41(26%)

–

–

Oligozoospermia

9(5.7%)

8.97 ± 4.78

8.6∗∗(5.25–13.15)

60 ± 8.2

58(53.5–67)

Asthenozoospermia

56 (35.5%)

73.28 ± 47.1

67.45∗∗(42.75–93.75)

36.03 ± 12.5

40∗∗(29.25–43.75)

Oligoasthenozoospermia

34 (21.5%)

7.14 ± 4.45

5.3∗∗(4.5–9.475)

26.47 ± 15.4

24.5∗∗(12–40.75)

3.4 Correlation of semen parameters with age

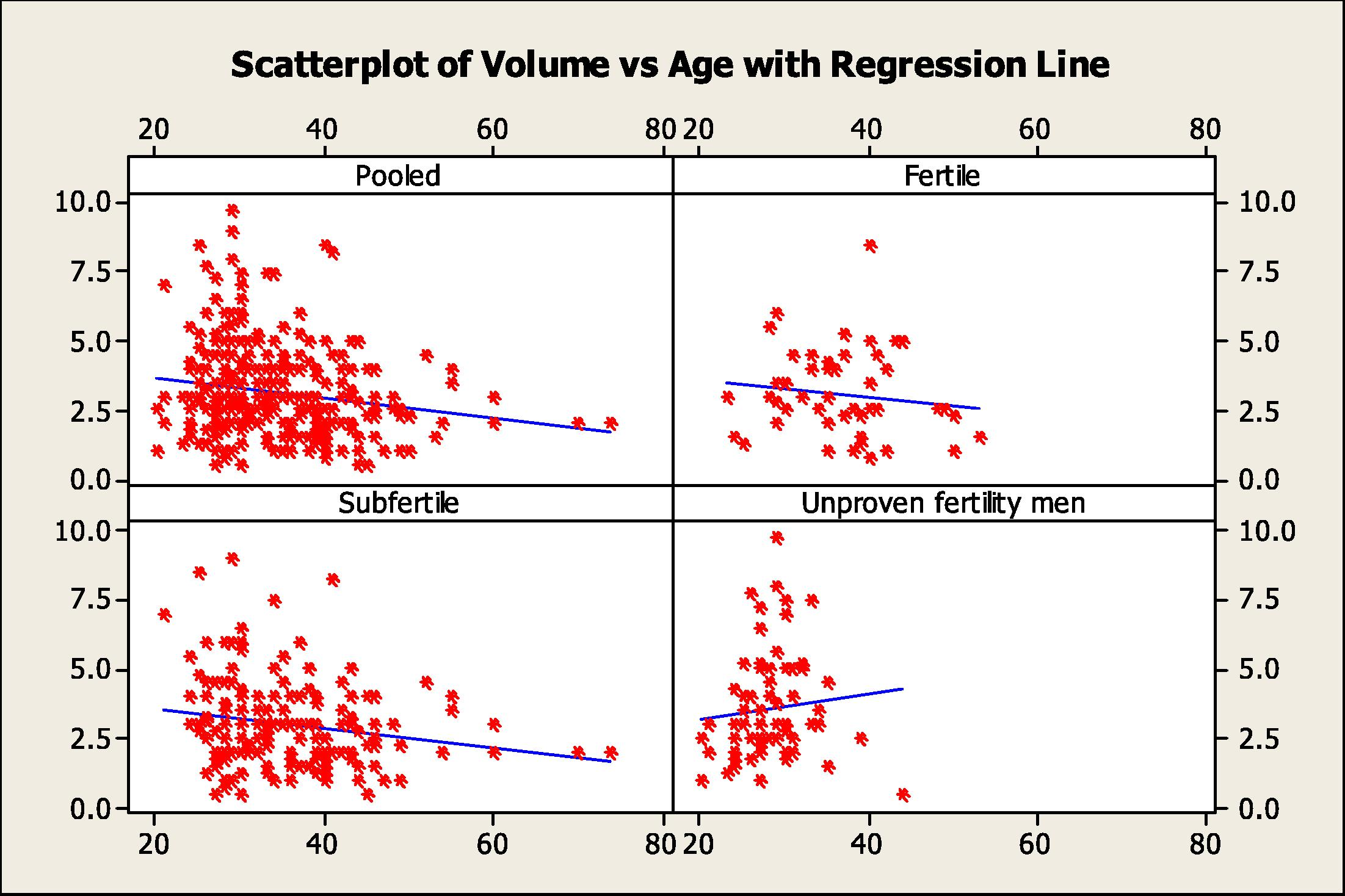

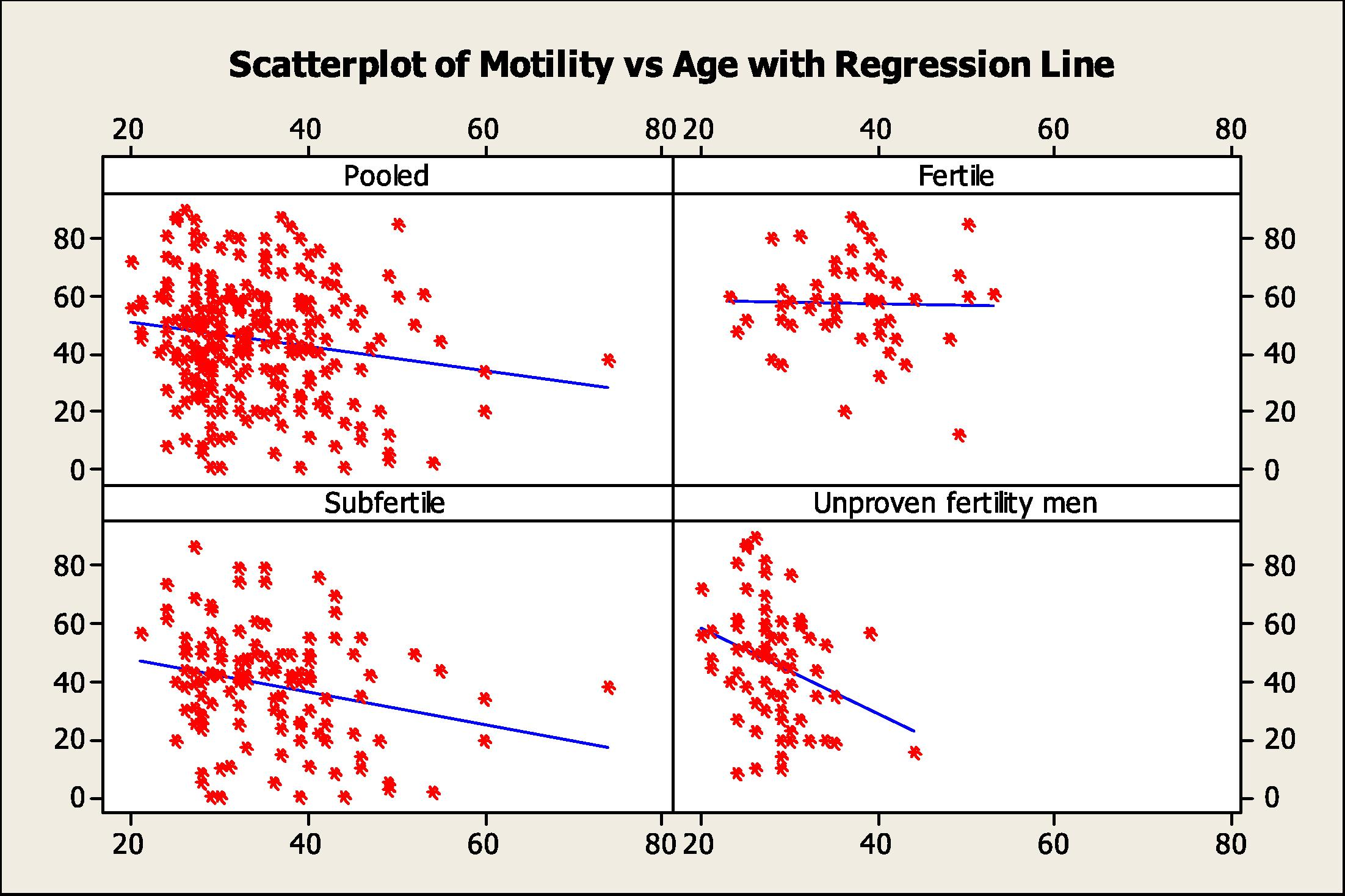

The results of age correlation with each of the semen parameters in the different groups (Figs. 1 and 2) were as follow:

Scatter plots with regression lines of semen volume versus age for the pooled data and the different study groups.

Scatter plots with regression lines of sperm motility versus age for the pooled data and the different study groups.

3.4.1 Fertile men

The age range of men in this group 23–53 years, the median was 37 (31.5–40.5) years. The age was positively correlated with most of the semen parameters but was only significant with the sperm concentration (r = 0.304, P= 034).

3.4.2 Subfertile men

The age range was 21–74 years, the median was 34 (29–40) years. There was an inverse correlation between age and each of the semen parameters but there was significant negative correlation with sperm motility (r = −0.235, P= 0.01).

3.4.3 Unproven fertility men

The age range was 20–44 years; the median was 27 (25–30) years. There was negative correlation with sperm motility (r = −0.318, P= 0.009).

3.4.4 Pooled data

The age range of all men was 20–74 years, the median was 32 (28–39) years. There was a significant negative correlation between age and semen volume (r = −0.152, P= 0.011) and sperm motility (r = −0.149, P= 0.023).

3.5 Correlation of sperm quality with the occupation

ANOVA test showed nonsignificant correlation between the occupation categories and semen parameters. Semen volume, sperm concentration and sperm motility were nonsignificantly higher in the military group (Table 3). (25–75) = 25th–75th percentile.

Occupation

Semen volume (ml)

Sperm concentration (106/ml)

Sperm motility (%)

Sperm abnormal morphology (%)

n

(Mean ± S.D.)

Median(25–75)

n

(Mean ± S.D.)

Median(25–75)

n

(Mean ± S.D.)

Median(25–75)

n

(Mean ± S.D.)

Median(25–75)

Civilian

213

3.07 ± 1.67

3(2–4)

213

58.31 ± 64.9

42.3(3.8–91.95)

170

43.4 ± 20.3

45(28.5–58)

159

65.50 ± 16.77

65(55–80)

Militaries

70

3.27 ± 1.74

3(2–4)

70

67.07 ± 58.65

57(17.97–96.35)

64

49.3 ± 20.73

48.5(34.25–62)

62

65.7 ± 16.07

65(55–80)

4 Discussion

This is the first study conducted, as a pilot one, to characterize the semen parameters in Saudi men in Riyadh city. The number of men of proven fertility was lower than the subfertile men due to the difficulty in collecting semen samples from men of general population as it is an embarrassing process unless they have to collect semen for analysis in the fertility clinics.

The social parameters of the fertile and subfertile groups were in the same range regarding age, duration of unprotected intercourse, and the occupation in each group. Hence the two groups were well matched, the social parameters of the unproven fertility men were also in the same range as the other two groups except age. Age was lower in the last group compared with other groups, as most of these men were single, due to the social customs and traditions of the Saudi society that encourage men to get married at young age.

The differences in the median values of the main semen characteristics between the fertile and subfertile groups were in consistence with those reported by Nallella et al. (2006) and Guzick et al. (2001). The values of semen parameters of each of fertile and subfertile men were compared with those reported in other populations; USA (Acacio et al., 2000; Guzick et al., 2001; Nallella et al., 2006), Europe (Auger et al., 1995; Bilotta et al., 1999; Andolz et al., 1999; Jørgensen et al., 2001; Lackner et al., 2005; Sripada et al., 2007), China (Li et al., 2009), Japan (Iwamoto et al., 2006), india (Marimuthu et al., 2003; Adiga et al., 2008) and Korea (Seo et al., 2000) (Tables 4 and 5).

Region

Selected subjects

n

Period of study

Age Year)

Semen volume (ml)

Sperm concentration (106/ml)

Sperm motility (%)

Sperm normal morphology (%)

Reference

Riyadh (present tudy)

Fertile men

49

2010

37 ± 7

3.03

116

57

45

Present study

Japan

Fertile

324

32.5 ± 4.5

3.7

53

62

42

Iwamoto et al. (2006)

Southwest China

Healthy men

1346

2007

20–40

2.3

77.8

70.9

–

Li et al. (2009)

USA

Fertile

696

–

33.5 ± 5

–

67 ± 50

54 ± 13

14 ± 5

Guzick et al. (2001)

Cleveland (USA)

Fertile

56

–

–

–

69.9

72.5

37.7

Nallella et al. (2006)

Copenhagen (Denmark)

Fertile

349

1996– 1998

31.5 ± 4.3

3.8

77

60

49

Jørgensen et al. (2001)

Paris (France)

Fertile men

207

1997–1998

32 ± 4.4

4.2

94

56

50

Jørgensen et al. (2001)

Turku (Finland)

Fertile men

275

1996–1998

30 ± 4.5

4.1

105

66

52

Jørgensen et al. (2001)

Edinburgh (Scotland)

Fertile men

251

1996–1997

32.5 ± 4.2

3.9

92

67

50

Jørgensen et al. (2001)

Scotland

Unknown fertility

577

1984–1995

27

3.4

104.5

61.3

–

Irvine et al. (1996)

Italy

Fertile

1068

1981–1995

–

61

66

63

Bilotta et al. (1999)

Paris

Fertile

1351

1973–1992

32–36

3.8

60

66

61

Auger et al. (1995)

Country

Selected subjects

n

Period of study

Age (year)

Semen volume (ml)

Sperm concentration (106/ml)

Sperm motility (%)

Normal sperm morphology (%)

Reference

Riyadh, (present study)

Subfertile men

160

2010

35.65 ± 8.67

2.97 ± 1.61

39.38 ± 49.54

39.28 ± 19.58

29

Present study

Northeast of Scotland

Infertile couples <20 × 106

4832

1994–2005

34 ± 6

–

61

49

–

Sripada et al., 2007

Munirka, New Delhi, India

Subjects attending the Fertility Clinic

1176

1990–2000

31.2

2.6 ± 0.1

60.6 ± 0.9

–

–

Marimuthu et al., 2003

South India

Infertile individuals

1610

2004–2005

–

2.64

26.61

47.14

19.75

Adiga et al., 2008

USA

Infertile couples

765

–

34.7 ± 4.9

–

52 ± 42

49 ± 15

11 ± 6

Guzick et al., 2001

Veina, Austria

Infertile men

7,780

1986–2003

31.6

–

10.25

21

15

Lackner et al., 2005

Korea

Healthy men with infertility

22,249

1989–1998

(32)21–40

–

60.5

–

–

Seo et al., 2000

Southern Tunisia, Sfax area

Men in infertile relationships

2940

1996 and 2007

36.0 ± 6.9

3.2 ± 1.6

96.1 ± 88.2

44.2 ± 12.7

25.0 ± 16.5

Feki et al., 2009

Sperm concentration of the fertile men was nearly two times higher than that recorded for the Americans or Danish fertile men and was also higher than the values reported for other populations, such as French, Scottish, Finnish, Italian, and Chinese men; whereas, Japanese men had the lowest sperm concentration.

Sperm motility was lower than that reported in different populations, i.e. American fertile men, Danish, Scottish and Finnish, Japanese and Italian men, but was similar to the results reported in French.

The percentage of sperm normal morphology was lower than that reported for the European populations, but higher than Japanese and in men in Cleveland (USA).

These differences could be due to endocrine, ethnic, geographical, environmental, nutritional, or life style variations. Specifically, the higher temperatures during most of the year in Riyadh city may affect sperm motility. In addition, genetic factors may be a factor where differences are due to different polymorphisms in the genes involved in influencing these parameters.

In subfertile men; sperm concentration was significantly higher than that the WHO (1999) reference (<20 × 106/ml) that could be due to the high percentage of the subfertile men (∼50%) categorized as subfertile for reasons other than the sperm concentration (normal: 99.27 × 106/ml and asthenospermia: 73.28 × 106/ml). Nallella et al. (2006) reported a large group of patients with male factor infertility that presented higher sperm concentration. This average value was also higher than that reported for subfertile men in South India and Vienna (Austria), and lower than that of American subfertile men.

Sperm motility of subfertile Saudis was lower than reported for subfertile men of other population such as in South India, Northeast of Scotland and USA, but not that reported in Vienna (Austria). These variations could be due to the relatively lower sperm motility in the general population of our study compared with other populations.

Around one third of the subfertile men were asthenozoospermic, and one fifth were oligoasthenozoospermic. This shows a relatively high percentage (∼57%) of Saudi subfertile men with abnormal sperm motility that was similar to the percentage reported in Los Angeles and Munirka (India). That percentage, followed by around 27% of the Saudi subfertile men who had sperm concentration <20 × 106/ml (5.7% oligozoospermic and 21.5% oligoasthenozoospermic). This percentage was higher than that reported for men in Los Angeles.

In comparison with other studies (Table 6), the prevalence of azoospermia (26%) was higher than that reported for subfertile men in South India, Los Angeles (USA), Northeast Spain, and Korea. Acacio et al. (2000), and Andolz et al. (1999) demonstrated that 4% and 6%, respectively, of the subjects were azoospermic. The subjects of their studies were of subfertile relationship so they were not diagnosed as subfertile men, and were also of unknown age. Adiga et al. (2008) recruited a population of subfertile men of undefined age of whom 7.2% were azoospermic. Seo et al. (2000) investigated a population that is similar to that in our study (subfertile men; 32 years) reporting that 19% of the population was azoospermic. This value was closer to the value reported in the present study.

Study

Region

Period of study (years)

Study subjects

Number of subjects and Age (year)

Oligozoospermia (%)

Asthenozoospermia (%)

Oligoasthenozoospermia (%)

Sperm abnormal morphology (%)

Azoospermia (%)

Present study

Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

2010

Subfertile men

160 35.65 ± 8.67

5.7

35.5

21.5

–

26

Acacio et al. (2000)

Los Angeles, USA

1994–1997

Male partners of women presenting for an infertility evaluation

1,385

18

51

–

14

4

Adiga et al. (2008)

South India

2005

Infertile individuals

1610

–

–

–

–

7.2

Marimuthu et al. (2003)

Munirka, New Delhi India

1990–2000

Subjects attending the Fertility Clinic

1176

31.21.8 (severe oligospermic were excluded)

63

–

–

Excluded

Andolz et al. (1999)

Northeast, Spain

1960–1996

Studied because of infertility

22,759

–

–

–

–

6

Seo et al. (2000)

Korea

1989–1998

Healthy men with infertility

22,249 32(range 21–40 year)

–

–

–

–

19

There was a significant correlation between age and the sperm concentration only in fertile men group that was not observed in other groups. This could be due to the lower variability in the age range and the small sample size of fertile group, of whom 57% fell in the age range of 30–40 years old, 13% were >45 years, and the oldest man was 53 years. The sample size of the subfertile group was higher, the age range was wider (50% were in the 30–40 years range), 13% were >45 years and the oldest man was 74 year. In the group of unproven fertility men, the sample size was higher than the fertile group, and they were younger with 26% in the age range 30–39 year old and the oldest was 39 years. Other studies (Table 7) agreed with the finding of this study suggesting no impact of age on sperm concentration (Cavalcante et al., 2008; Li et al., 2009; Seo et al., 2000). However, others were in disagreement with our results (Maya et al., 2009). Chen et al. (2004), reported nonsignificant impact of age on semen parameters in a sample size of 306, whereas Chen et al. (2003) reported an inverse relationship between age and semen parameters when the sample size and the age range were larger.

Study

Region

Period of study

Selected subjects

Number

Age average (age range)

Impact of age on semen parameters

Present study

Riyadh

2010

Fertile and subfertile men

209

35.9 ± 8.3

Inverse impact on volume and sperm motility

Seo et al. (2000)

Korea

1989–1998

Healthy men with infertility

22,249

32 (21–40)

None

Kidd et al. (2001)

Review study of the literature

1980–1999

–

–

30 and 50

Inverse impact, but not with sperm concentration

Chen et al. (2003)

Massachusetts, USA

1989–2000

From andrology clinic

551

–

Inverse impact on all parameters

Chen et al. (2004)

Massachusetts, USA

2000–2002

From andrology clinic

306

18–54 years (35.9 ± 5.6)

None

Cavalcante et al.(2008)

Northeast of Brazil

2002–2004

Men of conjugal infertility

531

37 ± 7.9

Inversely only with volume

Maya et al. (2009)

Medellin, Colombia

–

Men attending an andrology center

1364

⩽to30 years; between 31 and 39 years; and ⩾ to40 years

Inversely with all

Li et al. (2009)

Southwest, China

2007

Healthy men

1346

20–40

None

Mukhopadhyay et al. (2010)

Kolkata, India

1981–85 and 2000–2006

Men with infertility problems and normal sperm count

3729

33.24 ± 6.13 and 35.17 ± 5.043 (22–62)

A decline was seen in sperm motility with increasing age in both decades

There was an inverse correlation between age and sperm motility and semen volume in almost all groups in agreement with Kidd et al. (2001) suggesting that advanced age was associated with a decrease in semen volume, sperm motility, and sperm morphology but not sperm concentration. Cavalcante et al. (2008) showed an inverse effect of age on semen volume but not on other semen parameters. Maya et al. (2009) showed an inverse relationship between age and the main semen parameters. In contrast, some studies reported no impact of age on semen parameters (Li et al., 2009; Chen et al., 2004).

The contradiction between these studies could be due to differences in the age-range and the number of participated individuals, in addition, to other confounder factors such as ethnics, genetics, geographical location and the surrounding environment.

The relatively low sperm motility in the general population and the relatively high prevalence of azoospermia are of important implications with respect to infertility and further studies using large number of fertile and subfertile subjects with additional information on their smoking, socioeconomic condition, and life- style related factors are recommended.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that the values of sperm parameters were, in agreement with WHO criteria, significantly different in normal fertile from that of the subfertile Saudi men. Age has no effect on sperm concentration, viscosity, and morphology, but an inverse effect of age was observed on sperm motility and semen volume. As Riyadh city has the highest population (18.5%) among other Saudi cities, due to diverse socioeconomic factors, it is important to assess the semen quality in its different parts for further validation of the statement. In addition, further studies in other regions of Saudi Arabia are also needed.

5 Ethical statement

After IRB approval, all participants were asked to sign an informed consent form if they agreed to take part in this study.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to the fertility clinic (Dr, Sameer Abbas Clinic) in Riyadh city for their cooperation in conducting this study. The author acknowledges the advice and statistical analysis introduced by Mr. Abdulmunim Aldalee, Dr. Maha Omair; Professor Arjumand Warsy and Professor Khadigah Adham for helpful comments. This research was funded by the “Deanship of Scientific Research”, King Saud University through the Research Group Project No. RGP-VPP-069.

References

- Evaluation of a large cohort of men presenting for a screening semen analysis. Fertil. Steril.. 2000;73:595-597.

- [Google Scholar]

- Declining semen quality among south Indian subfertile men: A retrospective study. J. Hum. Reprod. Sci.. 2008;1:15-18.

- [Google Scholar]

- High frequency of sub-optimal semen quality in an unselected population of young men. Hum. Reprod.. 2000;15:366-372.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evolution of semen quality in North-eastern Spain: a study in 22 759 subfertile men over a 36 year period. Hum. Reprod.. 1999;14:731-735.

- [Google Scholar]

- Decline in semen quality among fertile men in Paris during the past 20 years. N. Engl. J. Med.. 1995;332:281-285.

- [Google Scholar]

- No secular trend over the last decade in sperm counts among Swedish men from the general population. Hum. Reprod.. 2011;26:1012-1016.

- [Google Scholar]

- Analysis of decline in seminal fluid in the Italian population during the past 15 years. Minerva Ginecol.. 1999;51:223-231.

- [Google Scholar]

- Relation between semen quality and fertility: a population-based study of 430 first-pregnancy planners. Lancet. 1998;352:1172-1177.

- [Google Scholar]

- Time series analysis of sperm concentration in fertile men in Toulouse, France between 1977 and 1992. BMJ. 1996;312:471-472.

- [Google Scholar]

- Interference of age on semen quality. Rev. Bras. Ginecol. Obstet.. 2008;30:561-565.

- [Google Scholar]

- Impact of seasonal variation, age and smoking status on human semen parameters: The Massachusetts General Hospital experience. Exp. Clin. Assist. Reprod.. 2004;1:2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Seasonal variation and age-related changes in human semen parameters. J. Androl.. 2003;24:226-231.

- [Google Scholar]

- The association of age and semen quality in healthy men. Hum. Reprod.. 2003;18:447-454.

- [Google Scholar]

- Semen quality decline among men in subfertile relationships: experience over 12 years in the South of Tunisia. J. Androl.. 2009;30:541-547.

- [Google Scholar]

- Semen analyses in 1,283 men from the United States over a 25-year period: no decline in quality. Fertil. Steril.. 1996;65:1009-1014.

- [Google Scholar]

- Semen quality in a residential, geographic and age representative sample of healthy Chinese men. Hum. Reprod.. 2007;22:477-484.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sperm morphology, motility, and concentration in fertile and subfertile men. N. Engl. J. Med.. 2001;345:1388-1393.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evidence of deteriorating semen quality in the United Kingdom: birth cohort study in 577 men in Scotland over 11 years. BMJ. 1996;312:467-471.

- [Google Scholar]

- Poor semen quality may contribute to recent decline in fertility rates. Hum. Reprod. J.. 2002;17:1437-1440.

- [Google Scholar]

- East-West gradient in semen quality in the Nordic-Baltic area: a study of men from the general population in Denmark, Norway Estonia and Finland. Hum. Reprod.. 2002;17:2199-2208.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of male age on semen quality and fertility: a review of the literature. Fertil. Steril.. 2001;75:237-248.

- [Google Scholar]

- Constant decline in sperm concentration in subfertile males in an urban population: experience over 18 years. Fertil. Steril.. 2005;84:1657-1661.

- [Google Scholar]

- Semen quality of 1346 healthy men, results from the Chongqing area of southwest China. Hum. Reprod.. 2009;24:459-469.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of trend in semen analysis for 11 years in subjects attending a fertility clinic in India. Asian J. Androl.. 2003;5:221-225.

- [Google Scholar]

- The effects of male age on semen parameters: analysis of 1364 men attending an Andrology center. Aging Male. 2009;12:100-103.

- [Google Scholar]

- Semen quality and age-specific changes: a study between two decades on 3,729 male partners of couples with normal sperm count and attending an andrology laboratory for infertility-related problems in an Indian city. Fertil. Steril.. 2010;93:2247-2254.

- [Google Scholar]

- Significance of sperm characteristics in the evaluation of male infertility. Fertil. Steril.. 2006;85:629-634.

- [Google Scholar]

- No evidence for decreasing semen quality in four birth cohorts of 1,055 Danish men born between 1950 and 1970. Fertil. Steril.. 1997;68:1059-1064.

- [Google Scholar]

- Semen quality over a 10-year period in 22,249 men in Korea. Int. J. Androl.. 2000;23:194-198.

- [Google Scholar]

- Trends in semen parameters in the northeast of Scotland. J. Androl.. 2007;28:313-319.

- [Google Scholar]

- The question of declining sperm density revisited: an analysis of 101 studies published 1934–1996. Environ. Health Perspect.. 2000;10:961-966.

- [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization., 1999. WHO laboratory manual for the examination of human semen and sperm-cervical mucus interaction. 4th ed. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.