Translate this page into:

Seed priming with carbon nanotubes and silicon dioxide nanoparticles influence agronomic traits of Indian mustard (Brassica juncea) in field experiments

⁎Corresponding author at: Department of Botany, University of Rajasthan, Jaipur 302004, India. sumita69@uniraj.ac.in (Sumita Kachhwaha)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

The present study demonstrates the effect of seed priming with carbon nanotubes and silicon dioxide nanoparticles on field performance of Indian mustard (Brassica juncea var. NRCDR 2) crop. A randomized block design study was conducted in research fields in which 3 groups of nano-primed seeds were sown in three replications. Two groups comprised treatments with 5 different concentrations (25, 50, 75, 100 and 125 μg/ml) of hydroxyl (–OH) functionalized multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNT) and silicon dioxide (SiO2) nanoparticles, and the third group was water treated seeds referred to as the control group. Sixteen different agronomic traits were considered, out of which three (leaf petiole length, siliquae length and number of seeds per siliqua) were found to have increased significantly, five traits (leaf length, length of main inflorescence, number of siliquae per plant, harvest index and biological yield) got decreased and nine traits (leaf width, plant height, number of primary and secondary branches, number of siliquae per main inflorescence, 1000 seed weight, oil content and seed yield) were not altered significantly as compared to control group. This first detailed report on field performance of a crop grown using seed priming as a mode of application of nanomaterials, demonstrated various alterations in agronomic characteristics of Brassica juncea, which were dosage dependent and were also influenced by the type of nanomaterials used to prime the seeds.

Keywords

Brassica juncea

Multi-walled carbon nanotubes

Precision agriculture

Seed priming

Silicon dioxide nanoparticles

1 Introduction

Nanotechnology applications have been witnessed into almost every walk of life in recent years, and agriculture also has not been left out of this influence (Linkov et al., 2011; Villaseñor and Ríos, 2018). Nanomaterials have been widely used in agriculture in the form of nano-fertilizers, nano-pesticides, vehicles for delivering genetic material, nano-sensors for detection of pesticides and pathogens, nutrient management, soil and water conservation, steady and controlled release of fertilizers and pesticides (de la Rosa et al., 2017; Ghormade et al., 2011). Role of nanomaterials in augmenting agricultural yield and productivity is still underexplored and sometimes questionable, hence more intensive research is required to investigate the effects of nanomaterials on plant growth, development and yield (Vishwakarma et al., 2017).

Both desirable as well as undesirable effects have been reported when plants are exposed to nanoparticles. Plants respond differently depending on the characteristics of applied nanoparticles such as shape, size, dosage applied and most interestingly the mode of application of nanomaterials (Lin and Xing, 2007; Oleszczuk et al., 2011; Syu et al., 2014). Moreover, application of nanomaterials in agriculture requires comprehensive investigation of their trophic transfer, ecosystem toxicity, animal, or human consumption due to incidental left-over residue in food products. Hence, the usage should be sustainable, economical, and ecofriendly. Some studies signify the relevance of seed priming technique (nano-seed priming) to improve stress tolerance and growth thereby, eliminating the associated risks to plants, environment and trophic transfer (Morales-Díaz et al., 2017).

CNT and SiO2 are amongst the ten most produced engineered nanomaterials (Keller et al., 2013) which have gathered convincing interest of researchers due to their applications in electronics, wastewater treatment, medical, pharmacy, agriculture, pigments, catalysis and others. (Rao et al., 2005; Zaytseva and Neumann, 2016).CNT and SiO2 have the ability to alter the metabolism of plants by entering the cells, thereby, influencing growth and yield (Khodakovskaya et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2009; Janmohammadi et al., 2016).

Rapeseed mustard is amongst the most economically important agricultural commodities, and it is the third major oilseed crops after soybean and groundnut. Rapeseed-mustard with production of 72.41 million metric tonnes (MMT) contributed 12.1% to the global oilseed production (597.27 MMT) during 2018–19 (Anonymous, 2020). India ranked 3rd after Canada and China; sharing around 10.38% of the global rapeseed-mustard production (76.24 million tonnes). The crop was sown in 6.23 million hectare land with production of 9.34 million tonnes of oilseeds during 2018–19 (Anonymous, 2019). Indian mustard (Brassica juncea L. Czern and Coss) is the most extensively cultivated species of rapeseed mustard group. This crop is mainly grown for oil-seed usage in India, also valued for its use as spice and condiment, and considered as third most important spice after salt and pepper (Katz and Weaver, 2003).

With plethora of reports on “nanomaterials driven agriculture” it is high time that this technology is developed as a large-scale commercial venture in fields, the success of which will define the future roadmap of ‘nano-agriculture’. The aim of present study was to see the field performance of the crop raised from seeds primed with nanomaterials (OH-MWCNT and SiO2 nanoparticles) before this method could be recommended for adoption by farmers. The plants were grown till maturity and their performance as compared with the plants raised from the seeds that have not been primed with any nanomaterials was compared to reach any final conclusion about the positive or negative effects of nanomaterials on different agronomic characters of Indian mustard.

2 Material and method

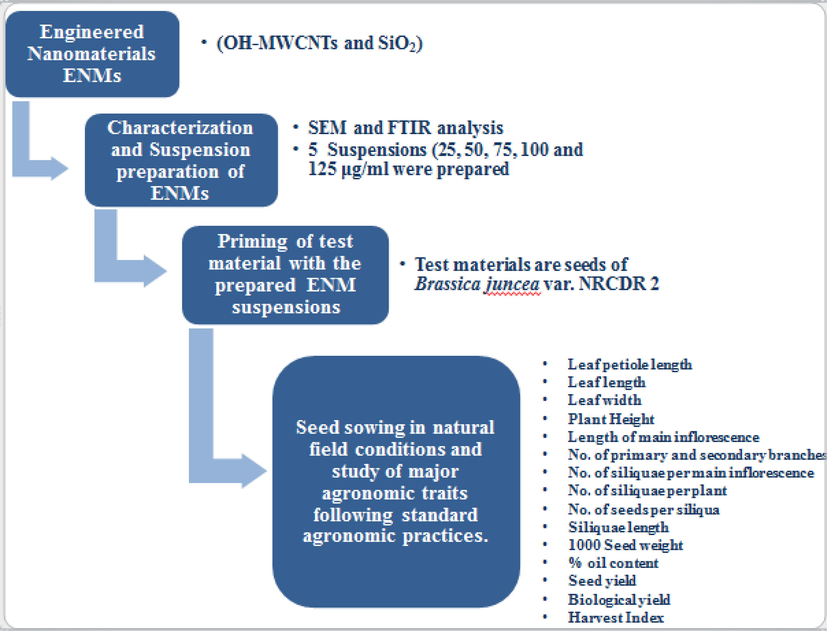

Overview of the present work of the studied agronomic traits of Brassica juncea upon seed priming with OH-MWCNTs and SiO2 nanoparticles is depicted in Fig. 1.

Overview of the present study on Brassica juncea raised from seeds primed with OH-MWCNTs and SiO2 Nanoparticles.

2.1 Plant and nanomaterials

Seeds of Brassica juncea var. NRCDR-2 were procured from ICAR-Directorate of Rapeseed Mustard Research (DRMR), Bharatpur, Rajasthan, India. Healthy, uniform, and free from any physical deformity seeds were screened and sampled out for use in the experimental study. MWCNT [–OH functionalized (3.1 wt%), length: 10–30 μm, OD: 10–20 nm and purity: min. 95%] and SiO2 [Hydrophilic, average particle size: 15 nm, specific surface area: 650 m2/g and purity: min. 99.5%] used in this study were obtained from Sisco Research Laboratories Pvt. Ltd.

2.2 OH– MWCNT and SiO2 characterization

Morphology of OH-MWCNTs and SiO2 were examined using EVO-18 Carl Zeiss Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) at an accelerating voltage of 20.0 kV at different magnifications, USIC, University of Rajasthan, Jaipur.

2.3 Nanoparticle suspension preparation and seed priming

Homogeneous suspensions of MWCNTs and SiO2 nanoparticles at 5 different concentrations (25, 50, 75, 100 and 125 μg/ml) were obtained by dispersing these in deionized water and then sonicating for 45 mins in an ultrasonic homogenizer (Yorko, WUC Series). Mustard seed lot (550gm) was divided into eleven batches of 50 gm each, out of which ten were consecutively transferred into Erlenmeyer flasks containing different concentrations of MWCNTs and nano SiO2 suspensions. Remaining one batch of seeds was suspended in deionized water to provide similar experimental conditions. To agitate the nano-suspensions uniformly and evenly all the flasks were kept on incubator shaker at room temperature for 6 hrs i.e. before the emergence of radicle. Thereafter, seeds were taken out and washed with tap water and then shade dried at room temperature for 24 h to complete the nano seed priming procedure (Hussain et al., 2019).

2.4 Experimental design

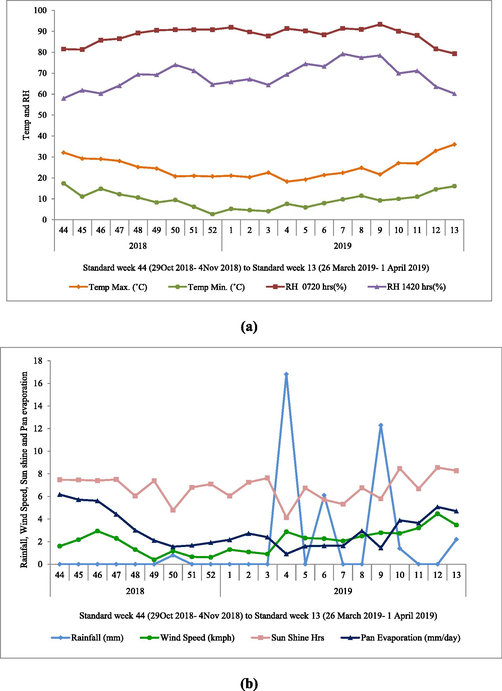

Nano-primed seeds were grown in the experimental fields of Directorate of Rapeseed-Mustard Research, Bharatpur, India situated at 77.30 °E longitude, 27.15 °N latitude, 178.37 m above mean sea level in rabi season in the year 2018–19. The experimental site was sandy loam soil and semi-arid weather with varied summer and winter temperature fluctuations. The meteorological data was recorded daily from the date of sowing till harvesting of the crop and then computed weekly. The recorded maximum and minimum temperature fluctuated in the range from 18.2 (4th week) to 36.0 (13th week) and 2.7 (52nd week) to 17.4 (44th week) respectively. Relative humidity was examined twice a day, one at 0720 hrs with highest (93.3%) in 9th week and lowest (79.3%) in 13th week and other one at 1420 hrs with highest (79.2%) in 7th week and lowest (58.0%) in 44th week. In the 22 weeks crop growing season maximum amount of rainfall was received in 4th week (16.8 mm) i.e. in the month of January which was quite favorable for plant growth. Wind speed and sunshine were relatively more intense in 12th week and pan evaporation in 44th week (Fig. 2).

Weekly meteorological data of Brassica juncea field from 29th October (sowing date) to 1st April (Harvesting date) (a) Temperature and Relative Humidity and (b) Rainfall, Wind Speed, Sun shine and Pan Evaporation.

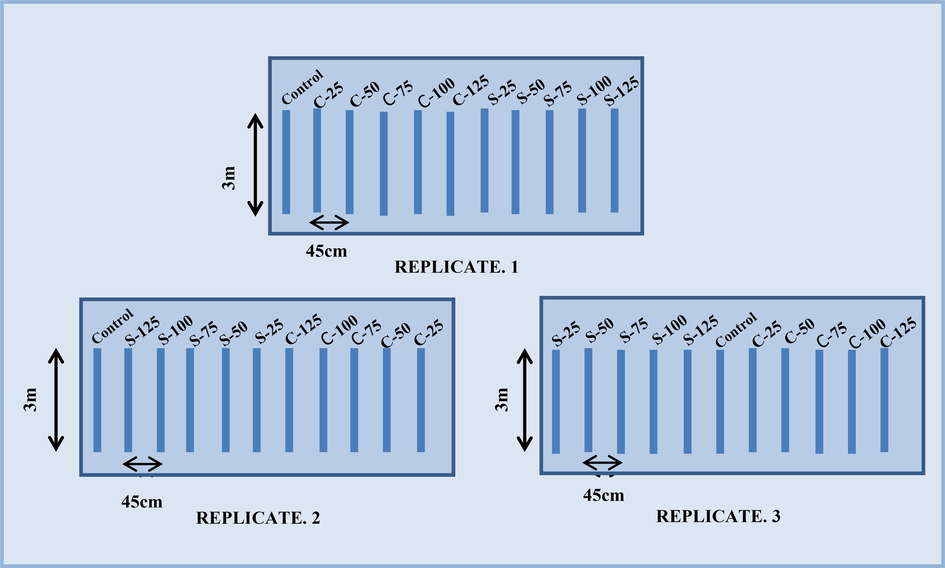

The experiment was conducted in randomized complete block design with 3 replications keeping single row plot of 3 m length to each treatment. Row to row and plant to plant spacing of 45 and 10 cm respectively was maintained (Fig. 3). Standard agronomic practices were followed to produce healthy crop. Sixteen agro-morphological traits were considered (including 3 leaf, 4 stem, 4 siliquae, 2 seed characteristics and 3 yield parameters).

Layout design for the experimental site showing the three replicates with the arrangement of sowing in rows according to the concentration levels of both the nanoparticles (C stands for OH-MWCNTs and S for SiO2 nanoparticles).

The observations were recorded as follows: the three leaf characteristics i.e., leaf petiole length; leaf length and leaf width were recorded on biggest leaf during bud formation to flower initiation stage using measuring scale. In stem characteristics i.e., plant height and length of main inflorescence were recorded using measuring scale and no. of primary and secondary branches were counted manually at maturity. All siliquae parameters were recorded on fully developed siliqua fruits in which siliquae length was measured using scale and number of siliquae per main inflorescence, no. of siliquae per plant and seeds per siliqua were recorded manually. Thousand seeds weight was recorded by counting 1000 seeds using seed counter and then weighing them and oil content was estimated using NIR, Dickey John Instalab 600 on random seeds collected from each treatment. In case of yield parameters i.e., seed yield and biological yield were recorded as seed weight after threshing and dry weight of plants before threshing, respectively. All leaf and stem parameters, no. of siliquae per main inflorescence and no. of siliquae per plant were recorded on randomly selected 5 plants per replicate hence, total data on 15 plants was recorded in all three replicates. Seeds per siliqua, siliquae length, 1000 seed weight and oil content were recorded on randomly selected 25 siliquae from 5 plants. Seed yield, biological yield and harvest index were calculated on plot basis.

2.5 Statistical analysis

All values are represented in tabular form as mean ± standard deviation (STDEV). Paired t-tests were performed for comparing average values of plants raised from nanoparticle (OH-MWCNT and SiO2) treated seeds with average values of control plants raised from untreated seeds for all the studied agronomic parameters. Complete statistical analysis was done in Microsoft office professional plus 2010, and considered significant at 95% confidence level (p < 0.05). Furthermore, % change reported in the table represents the amount of change recorded in terms of percentage for each agronomic trait between control and treated samples. Negative sign in % change values represent decrement in the values of agronomic traits with respect to control.

3 Results

3.1 Characterization of OH-MWCNTs and SiO2 nanoparticles

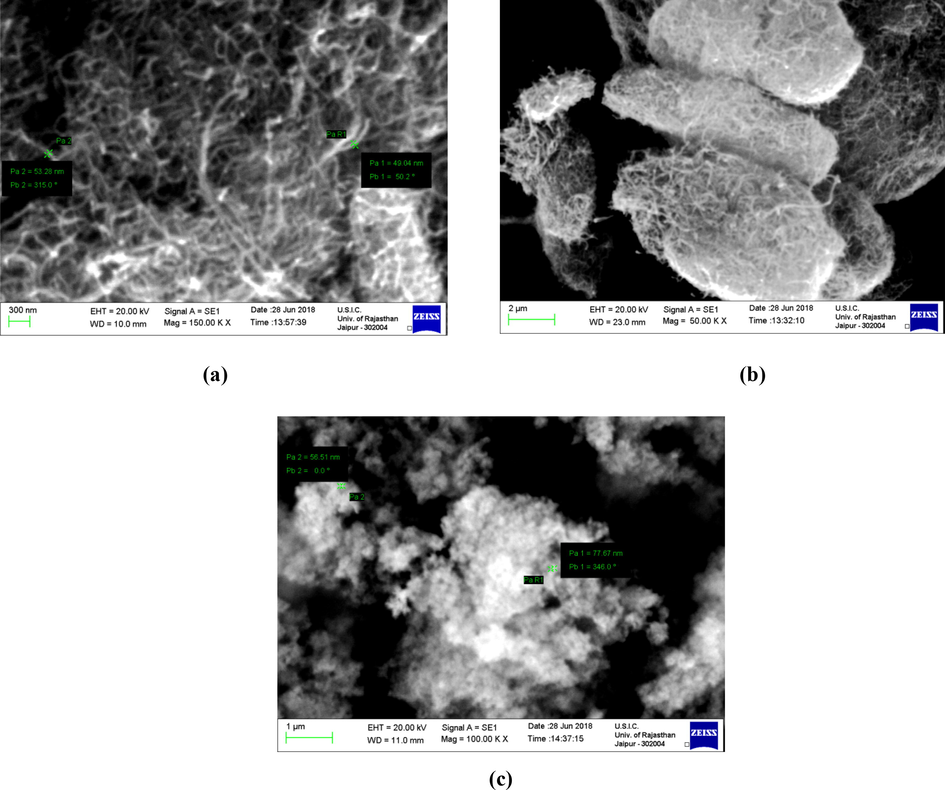

The results of Scanning Electron Microscopic analysis revealed the agglomerated structures of OH-MWCNT, cylindrical shape with average size of 54.64 nm and SiO2 nanoparticles observed as spherical particles present in aggregated form with average particle size of 80.75 nm (Fig. 4).

SEM Images: (a) and (b) (–OH) functionalized Multi-walled Carbon Nanotubes and (c) Silicon dioxide Nanoparticles.

3.2 Effect of OH-MWCNTs and SiO2 nanoparticles on agronomical traits

We found statistically significant (p-value < 0.05) and non-significant (p-value > 0.05) alterations in the agronomic characters upon treatment with OH-MWCNTs or SiO2 nanoparticles. Table. 1 incorporate the t-test and % changes calculated for the agronomic parameters which got altered (either increased or decreased) depending on specific concentration and type of nanoparticle used.

Sr. No.

Traits

Concentration

(μg/ml)MWCNT

P(T<=t) two-tail

SiO2

P(T<=t) two-tail

Mean ± STDEV

% Change

Mean ± STDEV

% Change

1

LPL, Leaf Petiole Length (cm)

Control

5.99 ± 1.33

5.99 ± 1.33

25

6.22 ± 1.83

3.90

0.66

7.3 ± 1.5

21.94

0.04

50

5.26 ± 1.48

−12.14

0.13

6.25 ± 2.24

4.45

0.69

75

6.37 ± 2.36

6.35

0.57

5.69 ± 1.87

−5.01

0.68

100

7.02 ± 1.99

17.26

0.05

5.79 ± 1.98

−3.23

0.75

125

7.72 ± 2

28.95

0.01

6.39 ± 1.58

6.68

0.35

2

LL, Leaf Length (cm)

Control

44.85 ± 6.1

44.85 ± 6.1

25

43.52 ± 6.12

−2.97

0.50

42.31 ± 4.28

−5.68

0.22

50

48.14 ± 4.86

7.33

0.15

39.38 ± 4.45

−12.20

0.02

75

43.88 ± 6.55

−2.17

0.64

42.27 ± 7.52

−5.75

0.31

100

39.52 ± 6.26

−11.89

0.01

43.35 ± 5.72

−3.36

0.51

125

42.25 ± 4.17

−5.81

0.21

38.88 ± 6.62

−13.32

0.03

3

LW, Leaf Width (cm)

Control

22.08 ± 3.14

22.08 ± 3.14

25

21.75 ± 3.02

−1.48

0.80

21.31 ± 2.55

−3.50

0.54

50

23.23 ± 3.99

5.22

0.40

20.09 ± 1.98

−9.00

0.09

75

20.57 ± 2.69

−6.85

0.14

20.81 ± 3.83

−5.77

0.38

100

19.73 ± 4.12

−10.63

0.11

21.4 ± 3.59

−3.07

0.63

125

21.04 ± 2.33

−4.71

0.33

19.32 ± 3.37

−12.50

0.06

4

PH, Plant Height (cm)

Control

226.03 ± 19.85

226.03 ± 19.85

25

224.77 ± 18.37

−0.56

0.87

219.33 ± 17.51

−2.96

0.40

50

230.37 ± 20.7

1.92

0.59

220.67 ± 18.98

−2.37

0.51

75

218.67 ± 19.13

−3.26

0.32

217.33 ± 18.79

−3.85

0.32

100

218 ± 22.98

−3.55

0.32

219.2 ± 18.43

−3.02

0.40

125

230.33 ± 22.64

1.90

0.61

221 ± 27.2

−2.23

0.59

5

LMI, Length of main inflorescence(cm)

Control

95.13 ± 13.93

95.13 ± 13.93

25

87.5 ± 13.18

−8.02

0.18

89.47 ± 22.95

−5.96

0.49

50

90.23 ± 13.66

−5.15

0.40

86.37 ± 12.5

−9.22

0.15

75

86.17 ± 14.12

−9.43

0.13

83.17 ± 15.63

−12.58

0.03

100

85.07 ± 16.02

−10.58

0.03

86.33 ± 14

−9.25

0.15

125

90.13 ± 14.69

−5.26

0.45

83.03 ± 16.06

−12.72

0.04

6

NPB, No. of Primary Branches

Control

9.07 ± 1.98

9.07 ± 1.98

25

9.33 ± 2.26

2.94

0.78

9.93 ± 2.84

9.56

0.40

50

9.47 ± 2.13

4.41

0.55

8.93 ± 1.53

−1.47

0.82

75

9.6 ± 1.99

5.88

0.51

8.87 ± 1.64

−2.21

0.78

100

9.4 ± 2.13

3.68

0.68

9.27 ± 2.15

2.21

0.83

125

9.8 ± 2.08

8.09

0.30

9.4 ± 1.5

3.68

0.60

7

NSB, No. of Secondary Branches

Control

28.8 ± 15.48

28.8 ± 15.48

25

24.4 ± 15.68

−15.28

0.41

28 ± 13.77

−2.78

0.90

50

23.53 ± 8.12

−18.29

0.22

21.2 ± 5.98

−26.39

0.12

75

27.67 ± 12.18

−3.94

0.82

25.47 ± 9.01

−11.57

0.44

100

22.73 ± 13.13

−21.06

0.31

25.4 ± 6.95

−11.81

0.54

125

29.53 ± 12.72

2.55

0.91

25.73 ± 10.5

−10.65

0.54

8

SMI, No. of Siliques/main infloresence

Control

56.87 ± 10.22

56.87 ± 10.22

25

51.2 ± 8.89

−9.96

0.07

52.73 ± 10.2

−7.27

0.27

50

55.47 ± 9.2

−2.46

0.77

54.33 ± 7.37

−4.45

0.44

75

54.33 ± 7.99

−4.45

0.46

50.33 ± 9.73

−11.49

0.14

100

54.13 ± 11.49

−4.81

0.40

52.27 ± 8.75

−8.09

0.23

125

58.6 ± 12.11

3.05

0.66

53.33 ± 16.82

−6.21

0.77

9

SPP, No. of Siliques/Plant

Control

651.2 ± 435.59

651.2 ± 435.59

25

512.27 ± 541.17

−21.33

0.43

492.53 ± 341.99

−24.37

0.29

50

482.33 ± 347.62

−25.93

0.29

382.87 ± 177.79

−41.21

0.05

75

457.4 ± 228.71

−29.76

0.16

437.07 ± 216.42

−32.88

0.11

100

430.93 ± 464.19

−33.82

0.24

447.53 ± 218.83

−31.28

0.18

125

566 ± 292.1

−13.08

0.55

504 ± 377.68

−18.48

0.46

10

SL, Silique Length (cm)

Control

5.67 ± 0.55

5.67 ± 0.55

25

5.77 ± 0.58

1.72

0.28

6.33 ± 5.51

11.62

0.29

50

5.87 ± 0.73

3.53

0.03

5.64 ± 0.61

−0.54

0.72

75

5.76 ± 0.45

1.55

0.27

5.73 ± 0.65

1.06

0.48

100

5.77 ± 0.61

1.76

0.29

5.83 ± 0.55

2.92

0.06

125

5.76 ± 0.55

1.62

0.24

5.52 ± 0.53

−2.59

0.09

11

SPS, No. of Seeds/silique

Control

15.71 ± 1.35

15.71 ± 1.35

25

15.79 ± 0.86

0.51

0.82

16.08 ± 0.81

2.38

0.63

50

16.09 ± 0.89

2.46

0.79

16.03 ± 0.81

2.04

0.69

75

15.76 ± 1

0.34

0.97

16.05 ± 0.4

2.21

0.64

100

15.64 ± 0.2

−0.42

0.95

16.6 ± 1.42

5.69

0.02

125

16.45 ± 0.68

4.75

0.20

16.13 ± 1.2

2.72

0.47

12

TW, Test weight or 1000 seed weight (g)

Control

4.78 ± 0.74

4.78 ± 0.74

25

4.74 ± 0.22

−0.84

0.95

4.47 ± 0.03

−6.49

0.54

50

4.56 ± 0.7

−4.53

0.81

4.51 ± 0.43

−5.72

0.60

75

5.04 ± 0.4

5.37

0.72

4.69 ± 0.47

−1.95

0.85

100

4.24 ± 0.41

−11.44

0.50

4.87 ± 0.81

1.88

0.87

125

4.65 ± 0.78

−2.65

0.62

4.4 ± 0.21

−7.88

0.51

13

GY, Grain yield (kg/ha)

Control

2855.57 ± 1052.24

2855.57 ± 1052.24

25

2120.11 ± 599.41

−25.76

0.12

2405.52 ± 642.42

−15.76

0.69

50

2197.46 ± 90.58

−23.05

0.36

2331.91 ± 643.76

−18.34

0.64

75

1993.8 ± 374.13

−30.18

0.19

2452.65 ± 492.43

−14.11

0.37

100

1819.79 ± 385.25

−36.27

0.34

2819.15 ± 598.9

−1.28

0.97

125

3362.67 ± 1324.01

17.76

0.74

3088.31 ± 1358.21

8.15

0.82

14

BY, Biological yield (kg/ha)

Control

14074.06 ± 5396.74

14074.06 ± 5396.74

25

10765.42 ± 3680.91

−23.51

0.08

11456.78 ± 2538.41

−18.60

0.60

50

12913.57 ± 3000.07

−8.25

0.51

10765.42 ± 1828.49

−23.51

0.49

75

11629.62 ± 5645.2

−17.37

0.01

11481.47 ± 1741.92

−18.42

0.35

100

9950.61 ± 3169.06

−29.30

0.38

14518.5 ± 5909.23

3.16

0.87

125

13209.86 ± 2090.32

−6.14

0.85

15234.55 ± 9617.17

8.25

0.80

15

HI, Harvest Index (%)

Control

20.8 ± 3.83

20.8 ± 3.83

25

20.54 ± 4.88

−1.28

0.84

20.87 ± 1.22

0.31

0.98

50

17.64 ± 4.04

−15.21

0.31

21.49 ± 2.96

3.29

0.71

75

20.08 ± 9.07

−3.47

0.89

21.25 ± 1.17

2.13

0.87

100

19.07 ± 4.41

−8.31

0.04

20.61 ± 5.45

−0.92

0.94

125

25.11 ± 7.14

20.71

0.32

21.96 ± 4.28

5.54

0.48

16

%OC, Oil Content (%)

Control

39.27 ± 1.89

39.27 ± 1.89

25

39.51 ± 0.37

0.61

0.86

40.21 ± 0.9

2.39

0.60

50

39.03 ± 0.25

−0.61

0.82

39.45 ± 0.62

0.46

0.90

75

40.03 ± 0.86

1.93

0.59

40.45 ± 0.81

3.01

0.44

100

39.33 ± 1.35

0.15

0.98

39.9 ± 1.07

1.61

0.53

125

40.26 ± 0.58

2.52

0.41

40.12 ± 0.35

2.17

0.45

Out of the sixteen agronomic parameters which were recorded, statistically significant increment in the values of three agronomic parameters as compared to control were noted viz. leaf petiole length got increased by 17.26% at 100 μg/ml (p = 0.0538) and 28.95% at 125 μg/ml (p = 0.0145) of OH-MWCNT treatments respectively, and 21% increment was observed at 25 μg/ml (p = 0.0410) of SiO2. Siliquae length got enhanced by 3.52% at 50 μg/ml (p = 0.0316) of OH-MWCNT and 2.92% at 100 μg/ml (p = 0.05860) of SiO2 and an increase in number of seeds/siliquae by 5.69% at 100 μg/ml (p = 0.0159) of SiO2 was noticed.

Statistically significant reduction in the values of five parameters with respect to control was observed namely leaf length got reduced by 11.89% at 100 μg/ml (p = 0.0140) of OH-MWCNT, and 12.20% at 50 μg/ml (p = 0.0238) and 13.32% at 125 μg/ml (p = 0.0301) concentration of SiO2 respectively. Reduction in length for main inflorescence by 10.58% at 100 μg/ml (p = 0.0317) of OH-MWCNT, 12.58% at 75 μg/ml (p = 0.0257) of SiO2. Number of Siliquae/ Plant got decreased by 41.21% at 50 μg/ml (p = 0.0467) concentration of SiO2. A decrease in biological yield (Kg/ha) by 17.37% at 75 μg/ml (p = 0.0085) and harvest index by 8.31% at 100 μg/ml concentration of OH-MWCNT (p = 0.0386) was detected.

In eight traits, no statistically significant changes were observed in the values. Leaf width, plant height, number of primary and secondary branches, number of siliquae per main inflorescence, 1000 seed weight, oil content and seed yield remained unaffected with all the concentration treatments of both OH-MWCNT and SiO2 nanoparticles.

As per our results, amongst all the studied parameters the values of only two parameters i.e. length of main inflorescence and number of siliquae per plant decreased (statistically significantly or insignificantly) at all the concentration treatments of both the nanoparticles. However, if individual nanoparticle was taken into consideration, OH-MWCNT reduced the biological yield but an increment in the values of numbers of primary branches and siliquae length at all the concentration treatments when compared to control was recorded. On the other hand, when compared to control, all the concentration treatments of SiO2 led to reduction in the values of leaf length, leaf width, plant height, no. of secondary branches and number of siliquae/main inflorescence but improved the values of no. of Seeds/Siliquae and oil Content.

From the data we observed that values of certain parameters displayed the same pattern of increment or reduction at all the treatment concentrations except only at a single concentration. In case of OH-MWCNT 10 parameters displayed such an effect viz. number of secondary branches, number of siliquae per main inflorescence, seed yield and harvest index (values decreased at all concentrations except 125 μg/ml where positive values were obtained). Leaf length and leaf width (values decreased at all other concentrations except 50 μg/ml at which positive values were obtained) whereas in case of leaf petiole length and oil content exactly opposite effects were noticed and at 50 μg/ml values decreased with respect to all other concentrations. 1000 seed weight decreased at all concentration treatments but increased only at 75 μg/ml and number of seeds per siliqua increased at all treatment concentrations but decreased at 100 μg/ml. However, in case of SiO2 number of such parameters is only 4 e.g. siliquae length and harvest Index increased at all concentration treatment except 50 μg/ml and 100 μg/ml respectively. On the other hand, the values of 1000 seed weight and seed yield diminished at all concentration treatments, except for 100 μg/ml and 125 μg/ml respectively, where values were found to get increased.

4 Discussion

Depending on the type and concentration used, nanomaterials can have positive or negative impact on plant growth and development as measured in terms of morphological, physiological, biochemical, anatomical, molecular, and agronomic characteristics (Mittal et al., 2020). Most of the reported studies have been conducted in controlled conditions of laboratory or green house, but farm based agricultural scale evidence are lacking, which would be imperative to conclude the role of nanomaterials on plant productivity under natural growth conditions. Such kind of pilot studies have constraints like cost of nanomaterials as testing in field conditions require high amount of nanomaterials in foliar spray (Behboudi et al., 2018), injecting directly to vegetative tissues (Corredor et al., 2009) or soil drenching (El-Naggar et al., 2020) and such methods may not be environment-friendly. In contrast to this, seed priming is a simple, cost-effective and safe technique as has been shown in rice, oats and wheat (Joshi et al., 2020, 2018b, 2018a) where uptake and internalization of MWCNTs through seed priming was shown using electron and confocal microscopy.

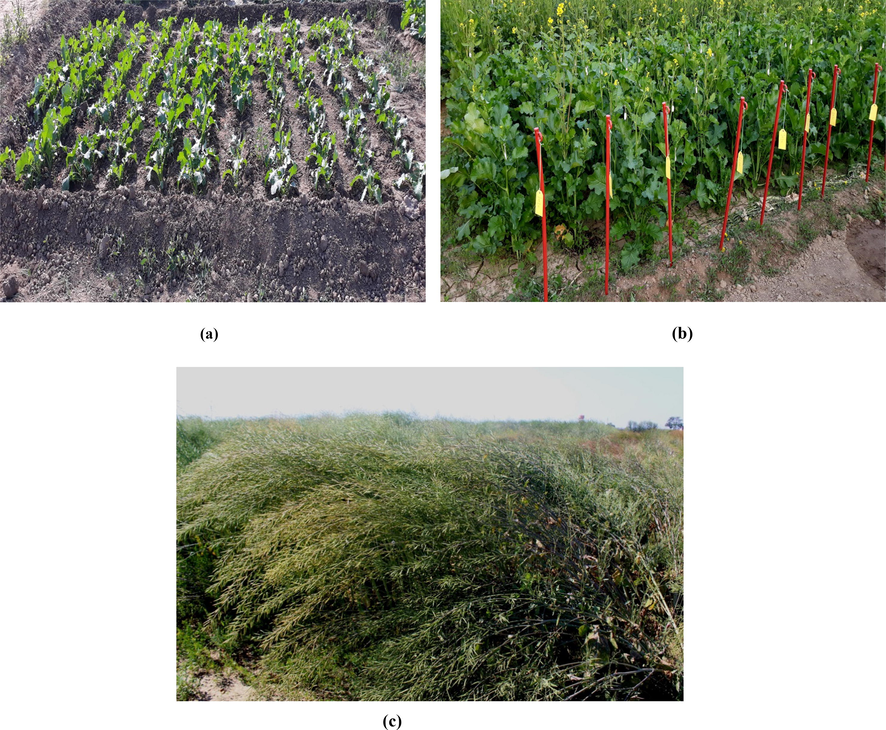

A large number of reports are available displaying the effect of OH-MWCNTs and SiO2 nanoparticles on many crop plants under controlled conditions and for limited phase of plant growth (Farhangi-Abriz and Torabian, 2018; Khodakovskaya et al., 2009; Mondal et al., 2011), but detailed studies under field conditions using seed priming as a mode of application of nanomaterials, to see the effect on various agronomic traits at different growth stages till maturity of the plant as reported in the present study (Fig. 5) is being reported for the first time. Focus of the present study was to determine the effectiveness of seed primed with a given range (25, 50, 75, 100, 125 µg/ml) of OH-MWCNTs and SiO2 nanoparticles in improving agronomic traits in Brassica juncea and to identify the agronomic traits most affected by particular concentrations of nanomaterials used.

Standing mustard crop in field experiment representing different growth stages (a) Vegetative (b) Flowering (c) Pod Formation. Each row represents particular concentration treatment of each nanoparticle.

The results elucidate that both the nanomaterials used in the present study induced varied alterations in different agronomic traits. Significant increment in the values of three parameters of leaf petiole length, siliquae length and number of seeds per siliqua was obtained. Petiole length and siliquae length was best with OH-MWCNTs at 125 µg/ml and SiO2 at 25 µg/ml, OH-MWCNT at 50 µg/ml, while SiO2 nanoparticles at 100 µg/ml concentration yielded maximum number of seeds per siliqua. Significant but negative changes were observed at higher concentrations of the nanomaterials used for leaf length, number of siliquae per plant, biological yield and harvest index. Other 8 traits (Leaf width, Plant height, Number of primary and secondary branches, number of siliquae per main inflorescence, 1000 seed weight, oil content and seed yield) remained unaltered as compared to control upon treatment with OH-MWCNT and SiO2 nanoparticles. Negative but non-significant alterations were more frequent than positive changes indicating that treatment of nanoparticles, in general, created some hindrances in plant growth and development. Two economically important traits of siliquae length and number of seeds per siliqua will be significant in terms of crop yield; however, consistency in plant response against the concentration of these nanomaterials remained a cause of concern and requires further refinement in terms of mode of application to ascertain commercial feasibility of seed nano-priming method.

Varied effects of nanoparticles on agronomic characters have been reviewed (Shang et al., 2019). An increase in leaf number, plant height (not statistically significant), number of secondary branches, siliquae per plant and seed yield in B. juncea (cv. pusa jaikisan) were observed upon foliar spraying with gold nanoparticles on 30-day old seedlings (Arora et al., 2012). However, an increase in total number of branches, number of siliquae per plant, seed yield, test weight were noted in the same variety of B. juncea (cv. pusa jaikisan) but no significant difference in harvest index when plants were sprayed with iron sulfide nanoparticles was observed (Rawat et al., 2017). Silver nanoparticle treatment provided highest number of pods per plant and seeds per pod with both, seed treatment and foliage spraying but combining both the methods of application, gave more pronounced effects and an increment in 100 seed weight and biological yield in Pisum sativum (Mehmood and Murtaza, 2017). Peanut plants, when grown in soil amended with iron oxide (Fe2O3), copper oxide (CuO), and titanium oxide (TiO2) displayed no significant alteration in shoot height, rather a reduction in 1000 grain weight was noticed (Rui et al., 2018). In soyabean, foliar spray treatment of both CNTs at 20 mg/L and SiO2 nanoparticles at 30 mg/L concentration induced a marked increase in all yield parameters from height of the plant to growth attributes to yield parameters along with nutritional components in comparison to control (Abdallah et al., 2021). A study conducted on barley revealed that chitosan NPs can significantly increase agronomic traits including the number of grains per spike, the grain yield and the harvest index compared to the control and also mitigate the harmful effects of drought stress (Behboudi et al., 2018).

(Joshi et al., 2018a) advocated the use of seed priming method in wheat, where considerable improvement in biomass and grain yield was obtained after treatment with MWCNT in potted plants. Enhancement in agronomic parameters such as spike length and weight, number of spikelets, number of grains, grain yield and 100 grain weight were observed (Joshi et al., 2018b) in a pot experiment initiated by priming oat seeds with MWCNT (70, 80 and 90 µg/ml). In another pot experiment, (Joshi et al., 2020) using same concentration levels of MWCNT, recorded an increase in weight and length of panicle, length and weight of spike, number of spikelets, grain number per plant and 100 grain weight in rice plants as compared to control. Unlike the present study, in all of these experiments (Joshi et al., 2020, 2018b, 2018a) potted plants were used, the results of which may vary under field conditions.

(Kole et al., 2013) also had similar observations in bitter melon at all tested concentrations; some produced significant effects while the remaining concentrations did not exert any significant impact and were more or less similar to the control. The reasons could be, firstly, at different concentrations the dispersion or diffusion may vary, and thus physical properties of nanomaterials also will vary, at larger concentrations there is more aggregation due to slow and less dispersion thus causing hindrance in the transportation or distribution of nanomaterials. Secondly, specific concentration and type of nanoparticles can have different zeta potential values, a parameter used for prediction of the long-term stability of nanomaterials and specific concentration can have particular dispersion ratios (Sankhla et al., 2016). Thirdly, the varied effect of nanoparticles is thought to be associated with shape, size, chemical composition, chemical structure, surface area, coating and mode of application of these nanoparticles (Cox et al., 2016; Maity et al., 2018). Also, various nanoparticles upon interacting with different plant species behave differently adding to the complexity of the process, involving three interlinked components i.e., nanomaterial, growth medium and the plant (Zaytseva and Neumann, 2016).

The result of present study suggest that seed priming with OH-MWCNTs and SiO2 nanoparticles play an important role in increasing few agronomic traits in mustard but the whole process has to be optimized for a given nanomaterial and further experimentation is needed to modulate the desired agronomic traits by choosing the right concentration of nanomaterial for different plant species. Nano-agriculture is still at its infancy and any contribution will pave the way for further advancement.

5 Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge this is the first detailed study where full life cycle of Brassica juncea with different concentrations of MWCNTs and SiO2 nanoparticles using seed priming as a method of application was conducted at the field scale.

Important agronomic traits were evaluated, and it was found that OH-MWCNTs and SiO2 nanoparticles have the potential to precisely control different agronomic traits i.e. specific response was observed upon priming with specific concentration of nanoparticles. Some traits such as leaf petiole length, siliquae length and number of seeds per siliqua got increased while other traits like leaf length, length of main inflorescence, number of siliquae per plant, harvest index and biological yield were reduced and many traits such as leaf width, plant height, no. of primary and secondary branches, number of siliquae per main inflorescence, 1000 seed weight, oil content and seed yield were not significantly altered.

We conclude, seed priming in Brassica juncea with OH-MWCNT and SiO2 nanoparticles was effective in increasing two economically important traits, siliquae length and number of seeds per siliqua at specific concentrations. If desired traits can be improved by seed priming with specific nanomaterials in a particular dosage, then this protocol has a potential to reach from lab to farmers.

Acknowledgements

Prerna Dhingra is thankful to Department of Science and Technology, New Delhi, for the INSPIRE fellowship. The authors want to express sincere gratitude to Dr. P.K. Rai, ICAR-Director of Directorate of Rapeseed Mustard Research (DRMR), Sewar, Bharatpur for allowing us to carry out the field trials and Mr. Guman Singh Gurjar, Senior Research Fellow at ICAR-DRMR for his immense support in this work. Authors are thankful to Dr. Shailesh Godika, Professor and Head at Department of Plant Pathology, Sri Karan Narendra Agriculture University, Jobner, Rajasthan for his guidance at each step. The authors also want to thank Department of Botany, University Science Instrumentation Centre (USIC) and RUSA 2.0, component 10:3, University of Rajasthan for providing the facilities to carry out the research work.

Author’s Contribution

The experiment was designed by Dr. Sumita Kachhwaha, Dr. S.L. Kothari and Prerna Dhingra. Material preparation and data collection was done by Prerna Dhingra and Sankalp Sharma. Analysis was performed by Jitendra Kumar Barupal and Shamshad-Ul –Haq. The experiment was conducted under the Supervision of Kunwar Harendra Singh. Characterization and Expertise on nanomaterials was given by Dr. Himmat Singh. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Prerna Dhingra and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The authors did not receive funds, grants or other support for the submitted work.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Response of some soyabean genotypes to spraying with potassium silicate and its effect on yield and its components, as well as on pod worm infestation rate. Asian J. Adv. Agric. Res.. 2021;15:38-52.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Oilseeds: World Markets and Trade. United States Department of Agriculture: Foreign Agricultural Service; 2020.

- Anonymous, 2019. Agricultural Statistics at a Glance 2019: Directorate of Economics and Statistics, Department of Agriculture, Cooperation and Farmers Welfare, Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare, Government of India, New Delhi.

- Gold-nanoparticle induced enhancement in growth and seed yield of Brassica juncea. Plant Growth Regul.. 2012;66:303-310.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of chitosan nanoparticles effects on yield and yield components of barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) under late season drought stress. J. Water Environ. Nanotechnol.. 2018;3:22-39.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Nanoparticle penetration and transport in living pumpkin plants: In situ subcellular identification. BMC Plant Biol.. 2009;9:1-11.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Silver and titanium dioxide nanoparticle toxicity in plants: A review of current research. Plant Physiol. Biochem.. 2016;107:147-163.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Physiological and biochemical response of plants to engineered NMs: Implications on future design. Plant Physiol. Biochem.. 2017;110:226-235.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Soil application of nano silica on maize yield and its insecticidal activity against some stored insects after the post-harvest. Nanomaterials. 2020;10:739.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nano-silicon alters antioxidant activities of soybean seedlings under salt toxicity. Protoplasma. 2018;255:953-962.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Perspectives for nano-biotechnology enabled protection and nutrition of plants. Biotechnol. Adv.. 2011;29:792-803.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Seed priming with silicon nanoparticles improved the biomass and yield while reduced the oxidative stress and cadmium concentration in wheat grains. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res.. 2019;26:7579-7588.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Janmohammadi, M., Amanzadeh, T., Sabaghina, N., Ion, V. et al., 2016. Effect of nano-silicon foliar application on safflower growth under orgainic and inorganic fertilizer regimes 22, 53–64. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1515/botlit-2016-0005.

- Multi-walled carbon nanotubes applied through seed-priming influence early germination, root hair, growth and yield of bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) J. Sci. Food Agric.. 2018;98:3148-3160.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Tracking multi-walled carbon nanotubes inside oat (Avena sativa L.) plants and assessing their effect on growth, yield, and mammalian (human) cell viability. Appl. Nanosci.. 2018;8:1399-1414.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Plant nanobionic effect of multi-walled carbon nanotubes on growth, anatomy, yield and grain composition of rice. Bionanoscience. 2020;10:430-445.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Katz, S., Weaver, W., 2003. Encyclopedia of food and culture.

- Global life cycle releases of engineered nanomaterials. J. Nanoparticle Res.. 2013;15

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Carbon nanotubes are able to penetrate plant seed coat and dramatically affect seed germination and plant growth. ACS Nano. 2009;3:3221-3227.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Nanobiotechnology can boost crop production and quality: First evidence from increased plant biomass, fruit yield and phytomedicine content in bitter melon (Momordica charantia) BMC Biotechnol.. 2013;13

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Phytotoxicity of nanoparticles: Inhibition of seed germination and root growth. Environ. Pollut.. 2007;150:243-250.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A decision-directed approach for prioritizing research into the impact of nanomaterials on the environment and human health. Nat. Nanotechnol.. 2011;6:784-787.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Carbon nanotubes as molecular transporters for walled plant cells. Nano Lett.. 2009;9:1007-1010.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Influence of metal nanoparticles (NPs) on germination and yield of oat (Avena sativa) and berseem (Trifolium alexandrinum) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. India Sect. B - Biol. Sci.. 2018;88:595-607.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Application of SNPs to improve yield of Pisum sativum L. (pea) IET Nanobiotechnol.. 2017;11:390-394.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Nanoparticle-based sustainable agriculture and food science: recent advances and future outlook. Front. Nanotechnol.. 2020;2

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Beneficial role of carbon nanotubes on mustard plant growth: An agricultural prospect. J. Nanoparticle Res.. 2011;13:4519-4528.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Application of nanoelements in plant nutrition and its impact in ecosystems. Adv. Nat. Sci. Nanosci. Nanotechnol.. 2017;8(1):013001.

- [Google Scholar]

- The toxicity to plants of the sewage sludges containing multiwalled carbon nanotubes. J. Hazard. Mater.. 2011;186:436-442.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A novel method for synthesis of silica nanoparticles. J. Colloid Interface Sci.. 2005;289:125-131.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Physio-biochemical basis of iron-sulfide nanoparticle induced growth and seed yield enhancement in B. juncea. Plant Physiol. Biochem.. 2017;118:274-284.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Metal oxide nanoparticles alter peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) physiological response and reduce nutritional quality: A life cycle study. Environ. Sci. Nano. 2018;5:2088-2102.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Biosynthesis and characterization of cadmium sulfide nanoparticles - An emphasis of zeta potential behavior due to capping. Mater. Chem. Phys.. 2016;170:44-51.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Applications of nanotechnology in plant growth and crop protection: A review. Molecules. 2019;24:2558.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Impacts of size and shape of silver nanoparticles on Arabidopsis plant growth and gene expression. Plant Physiol. Biochem.. 2014;83:57-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nanomaterials for water cleaning and desalination, energy production, disinfection, agriculture and green chemistry. Environ. Chem. Lett.. 2018;16:11-34.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Differential phytotoxic impact of plant mediated silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) and silver nitrate (AgNO3) on Brassica sp. Front. Plant Sci.. 2017;8

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Carbon nanomaterials: Production, impact on plant development, agricultural and environmental applications. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric.. 2016;3:1-26.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]