Translate this page into:

S-phase cell cycle arrest, and apoptotic potential of Echium arabicum phenolic fraction in hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cells

⁎Corresponding author. nabutaha@ksu.edu.sa (Nael Abutaha)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Plants have been used in the treatment of many diseases. The aim of the present investigation was to assess the cytotoxic potential of Echium arabicum extracts against liver and colon cancer cells. The plant was extracted using Soxhlet apparats and ultrasound-assisted hydrolysis. The phenol and antioxidant activity was assessed using Folin–Ciocalteu and DPPH method respectively. The cytotoxicity was determined using MTT and lactate dehydrogenase release assay. The apoptosis study was conducted using DAPI, and Acridine orange/ethidium bromide and confirmed by Caspase 3/7 Fluorescence reagent, and the Cell cycle analysis was carried out using Muse Cell Analyzer. E. arabicum had cytotoxic properties with half inhibitory concentration (IC50) values of 61.6 ± 0.6, 66.4 ± 0.9, 71.9 ± 0.8, and 38.3 ± 0.3 μg/mL against LoVo, HCT116, HuH-7 and HepG2 respectively using MTT assay. Interestingly, the phenolic fraction showed less cytotoxicity at the highest concentration tested on normal human liver (Chang) cells. Staining of HepG2 cells with DAPI and AO/EB post treatment with phenolic fraction (40 and 60 µg/mL) decreased the number of viable cells and exhibited typical features of apoptosis like blebbing of plasma membrane with an increase in the Caspase-3/7 activity. Furthermore, cell cycle study revealed that E. arabicum induced a S-phase arrest in HepG2 cells. The coefficient of determination (R2 = 0.997) and the Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r = 0.998) between DPPH activity and total phenolic content was highly correlated. These results demonstrate that phenolic fraction from E. arabicum might have a strong potential as chemopreventive agent in liver cancer.

Keywords

Echium arabicum

Apoptosis

Phenols

Antioxidant

Liver cancer

Caspase-3/7

1 Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CC) and liver cancer (LC) are the third (Zeriouh et al., 2017) and sixth (Bray et al., 2018) most commonly prevalent cancer worldwide respectively. Worryingly, the increasing cases of colon and liver cancer recently became a major health concern (Dasgupta et al., 2020). About 70% of colorectal cancer patients will metastasize to the liver (van de Velde, 2006) due to its anatomical situation. A significant improvement of cancer treatment has been achieved with different diagnostic methods and treatment programs. Despite these developments, metastasis, disease recurrence and multidrug resistance to chemotherapy remain a major difficulty in its successful management (Peters, 2020). There are more than 500 compounds isolated from natural sources such as plants and microorganisms, which have antioxidant, anticancer, and antiangiogenic activities. Paclitaxel, etoposide, irinotecan, and vincristine are some of compounds isolated from plants and are used in treatment of cancer (Shah et al., 2020; Sivasankarapillai, 2020).

There are several secondary metabolites reported for their anticancer activity such as phenol, alkaloids, terpenoids, and many more. Phenols are secondary metabolites that are distributed in the plant kingdom mainly in higher plants (Lin et al., 2016). Phenols exhibit different biological activities, such as antiproliferative, anti-aging, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory (Moo-Huchin et al., 2015). In fact, phenols are among the most active compounds that have already been reported for their anticancer activities such as hydroxycinnamates, flavonoids, coumarins, hydroxybenzoates, xanthones, stilbenes, chalcones, and lignins (Anantharaju et al., 2016). The chemical structure of each compound being strongly correlated with its chemical, physical, and biological properties (Glevitzky et al., 2019).

Different studies have validated their ethnomedicinal properties revealing that Echium spp. possesses antiviral, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, analgesic, antibacterial and anxiolytic effects (Abolhassani, 2010). Many species have been documented for their pharmacological properties in the Middle East. Previous investigations from Saudi Arabia, E. arabicum (Boraginaceae family) have demonstrated its antitrypanosomal and antiplasmodial properties (Kuete et al., 2013) but to our knowledge, no reports have been carried out on their cytotoxic activities.

Therefore, the current study aimed to assess the phytochemical and antioxidant activity of E. arabicum extracts growing wild in Saudi Arabia, explore the cytotoxicity of E. arabicum extracts against different cancer cells, and study the possible death mode of the HepG2 cells induced using different assays.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Collection and extraction of plant material

Echium arabicum (Fig. 1) was collected from Riyadh (24°49′24.1″N 46°27′29.4″E) during March 2021 and a herbarium specimen (KSU-NAT049) was deposited at the Bio-product Research Chair, king Saud University, Saudi Arabia. The whole plant (leaf, stem,) was washed with distilled water and air-dried before extraction. Air-dried material was then ground into fine powder and extracted.

Image of Echium arabicum growing wild in Riyadh desert.

2.1.1 Soxhlet extraction

The ground powder was extracted using the Soxhlet extractor (WiseTherm, Korea). The powder (10 g) was filled in a thimble and extracted sequentially using different solvents namely hexane (Sigma, Germany), chloroform (Winlab, UK), ethyl acetate (fisher, UK, and methanol (Sigma, Germany) for 20 h. Each extract was filtered, and finally evaporated at 45 °C under reduce pressure (Heidolph, Germany). The dry crude extract was re-suspended in methanol to obtain a stock concentration of 10 mg/mL.

2.1.2 Extraction of alkaloid

Powdered plant material (8 g) was wetted with 25% NH4OH (15 mL) and solvent extracted with ethyl acetate (300 mL) for 72 h and then filtered and evaporated at 40 °C under reduce pressure. The residue was suspended in H2O and acidified to pH 3 using H2SO4 (18.4 M). It was then extracted with diethyl ether to get rid of neutral, lipophilic, and acidic material. The remaining solution was basified to pH 9 with 25% NH4OH and extracted with chloroform. The extract was washed 3 times with distilled water to neutral pH and evaporated under reduced pressure to dryness to obtain crude alkaloids extract. Stock solution was prepared (10 mg/mL) using methanol (Djilani et al., 2006).

2.1.3 Extraction of phenolic compounds

Ultrasound-assisted hydrolysis of E. arabicum powder (8 g) was carried out using NaOH (2 M) for 24 h at 65 °C. After hydrolysis, the sample was acidified (pH = 3) and extracted with ethyl acetate (250 mL) three times. The extracts were combined, washed 3 times with distilled water and dried under a reduced pressure and a stock solution was prepared (10 mg/mL) using methanol.

2.2 Determination of phenolic and flavonoid contents

Folin–Ciocalteu (FC) method (Abutaha, 2020) was used to estimate the total phenolic contents (TPC) of extracts in a 96-well plate. Briefly, 2 µL of extract (1 mg/mL) solution was mixed with 20 µL FC reagent (Alpha, India). After 10 min, 80 µL of Na2CO3 (7.5%) was then added and incubated at 25 °C for 2 h. The absorbance was read at 765 nm. The data were expressed as µg/ml using gallic acid standard.

The flavonoid contents were assessed (Abutaha, 2020) in a 96-well plate. Two microliters of extract solution or quercetin (5–100 µg/mL) (Sigma, USA) were added with 4 µL of AlCl3 (10%, w/v), 4 µL CH3COOK and 112 µL distilled H2O. The mixture was left for 30 min in the dark and the absorbance was read at 415 nm. The data were expressed as µg/mL using quercetin standard.

2.3 DPPH radical scavenging activity

The radical scavenging potential (RSP) of the phenolic fraction was assessed using the DPPH (Sigma, USA) assay (Abutaha, 2020). Briefly, 2 µL of extract (1–100 µg/mL) in methanol was added to 198 µL of DPPH (0.008% w/v in methanol) solution. The mixtures were kept for 30 min at 25 °C and absorbance (517 nm) was measured against a blank (198 µL DPPH and 2 µL methanol). The percentage of DPPH• scavenging (RSP %) was calculated. scavenging % = [(AC – AE)/AC] × 100 where AC = control absorbance and AE = test extract absorbance.

2.4 Cytotoxicity assay

Human colon (HCT-116 and LoVo) liver (HuH-7, and HepG2) cancer cells and normal liver cells Chang (DSMZ, Germany) were maintained at 37 °C, 5% CO2 in DMEM (UFC Biotech, KSU) and supplemented with antibiotic mixture (1%) (Invitrogen, USA) and fetal bovine serum (10%) (Gibco, USA). Cells (5 × 105 cells/mL) were cultivated in a 24-well cell culture plate (NIST, China) and left for attachment overnight. Next, the cells were treated with different concentration from 100 to 6.2 µg/mL. 0.01% of methanol was used as a control. The percent viability of cells was carried out using MTT test after 24 h of exposure. MTT solution (5 mg/mL) was added and after 2 h of incubation the media was aspirated from each well. Then, 1 mL of 0.1%HCl-isopropanol was added and processed as reported earlier (Abutaha, 2020). The absorbance (550 nm) was measured using ChroMate® plate Reader (ChroMate, USA). The assay was carried out in three repetitions and plotted using OriginPro8.5.

2.5 Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release

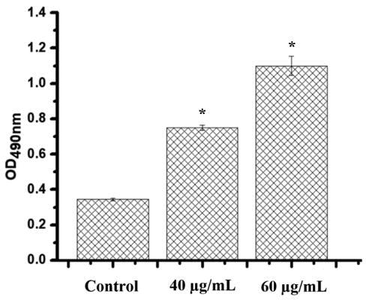

HepG2 cells were incubated with active extract as illustrated in the previous section. The released LDH was assessed at different concentrations (100 to 6.2 µg/mL) using the LDH Detection kit (Sigma, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. The results were reported as the optical density (490 nm) of the control and treated groups.

2.6 Measurement of extracellular nitric oxide (NO)

The extracellular NO was assessed by Nitrite determination. The NO − level in cell media was assessed using two different concentrations. Briefly, equal volume of cell culture medium (100 µL) and Griess reagent (Sigma, Germany) were mixed together for10 min at 25 °C, and the absorbance was measured at 560 nm. The results were reported as the optical density of the control and treated groups.

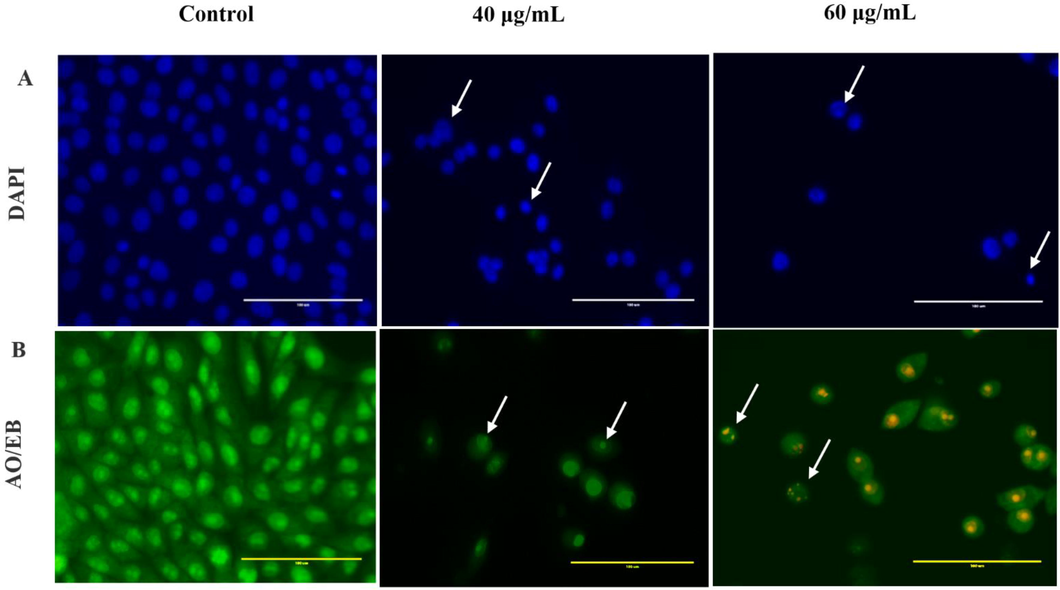

2.7 Nuclear morphological changes using 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining

Cells were seeded as specified in the previous section and treated with 40 and 60 μg/mL of E. arabicum phenolic fraction. HepG2 cells were fixed in ethanol for 10 min and then washed with PBS and incubated with DAPI (Life Technology, USA) for 10 min and imaged using a fluorescence microscopy (Evos, USA). Acridine orange/ethidium bromide (AO-EB) staining HepG2 cells were treated as in the previous section, then 2 μg/mL of AO-EB (1:1, v/v) was added and directly imaged using fluorescence microscopy (EVOS, USA).

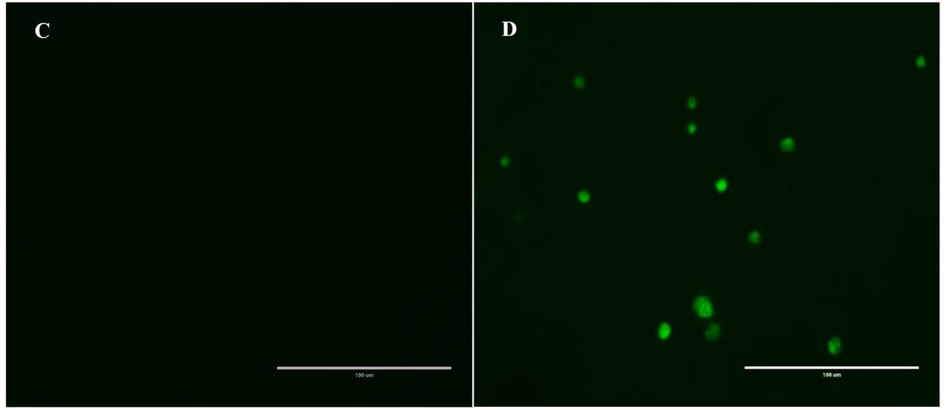

2.8 Caspase 3/7 fluorescence detection

HepG2 cells were seeded and treated with E. arabicum phenolic fraction (40 μg/mL) as specified in the previous section and after 24 h the cells were labeled with 5 μM of caspase-3/7 green detection reagent (Invitrogen ,USA) for 30 min at 37 °C. Images were taken using fluorescence microscopy.

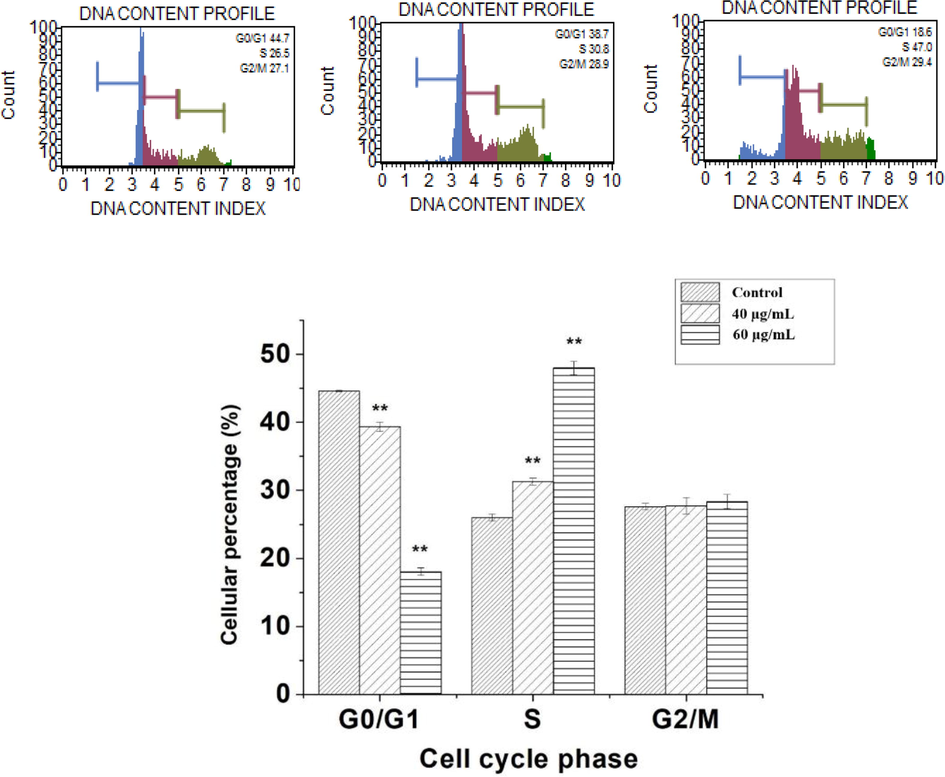

2.9 Cell cycle analysis

Cells were seeded as specified in the previous section and treated with 40 and 60 μg/mL of E. arabicum phenolic fraction for 24 h and processed as reported previously (Abutaha, 2020). Ethanol fixed HepG2 cells were kept at 4 °C for 48 h and stained with Muse Cell Cycle Kit (Millipore, Germany). Percentage of cells in different cell cycle phases was assessed using Muse Cell Analyzer (Millipore, Germany). Cells were divided into three categories: G0/G1, S and G2/M. The data were compared with the negative control cells.

2.10 Statistical analysis

Data were obtained from triplicate experiments and presented as the mean ± standard deviation. T-test was used for comparison of result using Excel software, where p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3 Results

3.1 Yield of plant extracts

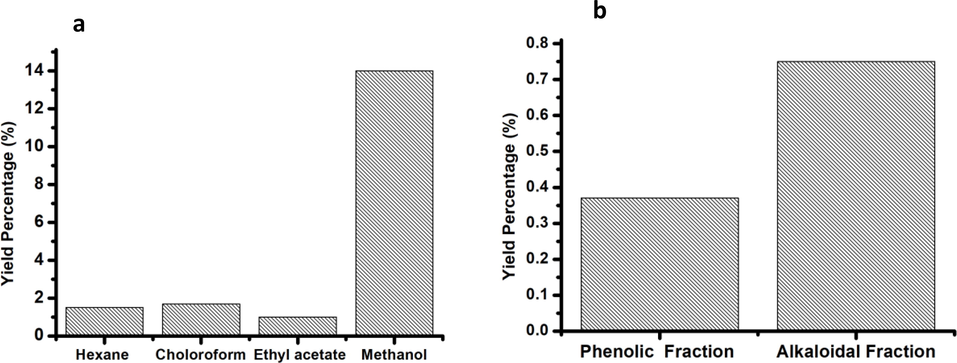

A total of six extracts were prepared from whole plant (stem, leaves, and flowers) of E. arabicum. The extract yields of the different extraction methods are shown in Fig. 2. The highest yields of extraction were recorded from the methanol extract (14%), whereas the lowest yields were obtained from ethyl acetate (1%) extract. However, the yield of phenol and alkaloid extract was 0.37% and 0.75% respectively.

(a) Yield of Echium arabicum extracts using solvents of different polarity in Soxhlet apparatus and (b) the yield of phenolic and alkaloidal fractions.

3.2 Total phenol and flavonoid contents

The analysis of phenol and flavonoid contents of phenolic fraction was estimated to be 269.9 and 178.1 µg/mL respectively.

3.3 DPPH radical scavenging activity

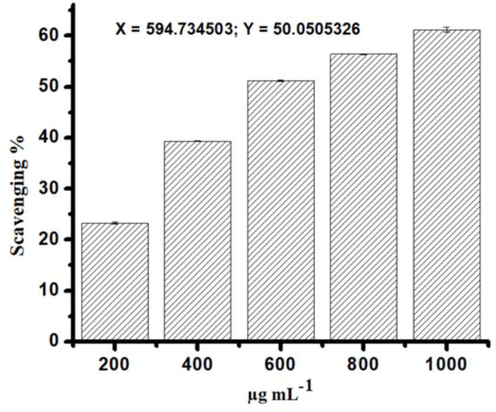

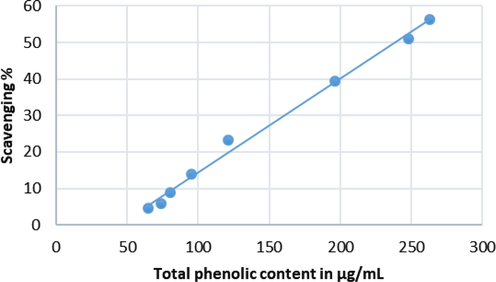

Initially one concentration (1 mg/mL) was used to test the antioxidant activity for all extracts. The best antioxidant activity, was reported for the phenolic fraction which was the highest (60.65 %), followed by ethyl acetate (17.14%) and chloroform (3.91%) extracts. However, for the best antioxidant activity (phenolic fraction) among the extracts tested, five varying concentrations (200 to 1000 µg/mL) of phenolic fraction was further tested and showed increasing percentage of inhibition. The scavenging activity of phenolic fraction was increased in a concentration dependent way (Fig. 3). The EC50 value was calculated to assess the concentration of the extract needed to inhibit 50% of radical. The observed EC50 value was 594.7 ± 0.02 µg/mL. The correlation of DPPH scavenging activities with the total phenolic content are shown in Fig. 4. The coefficient of determination (R2 = 0.997) and the Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r = 0.998) between DPPH activity and total phenolic content was highly correlated. This correlation confirms the phenolic compounds are the major contributor to the antioxidant properties of the phenolic fraction.

The radical scavenging activity of Echium arabicum phenolic fraction represented by percentage of inhibition.

Correlation between total phenolic content and DPPH radical scavenging activity of Echium arabicum phenolic fraction. Coefficient of determination, R2 = 0.993 and correlation coefficient, r = 0.996.

3.4 Cytotoxicity and morphology

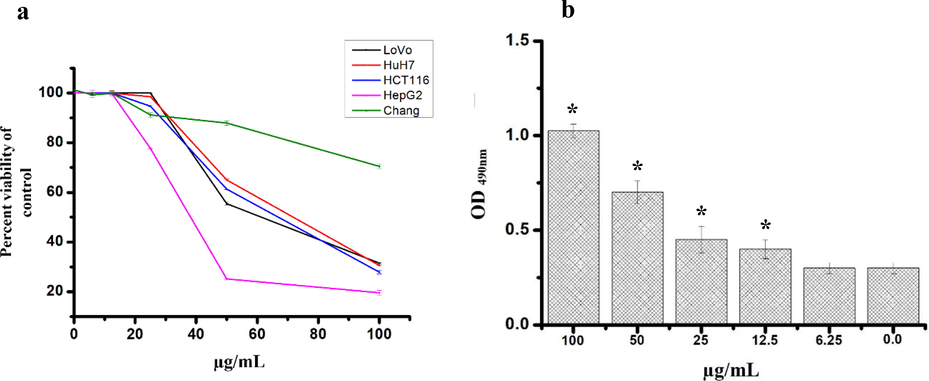

To explore the cytotoxicity effect of hexane, chloroform, ethyl acetate, methanol extract as well as phenol and alkaloid extracts MTT assay was used. The anticancer activity was assessed against five different cell lines, namely human colon (HCT-116 and LoVo), liver (HuH-7, and HepG2) cancer cells and one normal cell line (Chang). Only the phenolic fraction (Fig. 5a) from all the other extracts tested (results are not shown) showed anticancer activity against HCT-116, LoVo, HuH-7, and HepG2 lines. The IC50 values were found to be 61.6 ± 0.6, 66.4 ± 0.9, 71.9 ± 0.8, and 38.3 ± 0.3 μg/mL against LoVo, HCT, HuH-7 and HepG2 respectively. The results showed a reduced in cell viability with the increase of phenolic fraction concentrations (Fig. 5a). Chang cells showed less toxicity to the phenolic fraction of E. arabicum compared to other cancer cell lines tested. At the highest concentration tested (100 µg/mL), the cell showed 70.5 ± 0.9 viability. Further confirmation of cytotoxicity was assessed using LDH enzyme assay. LDH is a marker of membrane integrity that is released into the media. The phenolic fraction showed an increase in the release of LDH with the increasing concentration of phenolic fraction from HepG2 cells from 6.25 to 100 μg/mL, signifying disruption of cell membrane structure (Fig. 5b). We also observed a Statistically significant increase in the levels of NO produced in the presence of phenolic fraction after 24 h of incubation (Fig. 6).

(a) The cytotoxic effect of phenolic fraction of Echium arabicum extract after 24 h of treatment using different cancer cells and normal human liver cell (Chang) using MTT assay. Results are expressed as a percentage of the control, assuming that the viability in untreated cells is 100%. (b) The effect of different concentrations of phenolic fraction on HepG2 cells after 24 h of treatment using the LDH cytotoxicity test. 0.01% methanol was used as control. All the data are presented as mean ± SD of three independent tests. The difference was considered significant at P < 0.05.

The effect of different concentrations of phenolic fraction of Echium arabicum extract in HepG2 NO production after 24 h of incubation. The data are presented as mean ± SD of three independent tests. The difference was considered significant at P < 0.05.

The DAPI staining of phenolic fraction were carried out only for HepG2 cells. Microscopic assessment of treated cells revealed reduction in number of cells, loss of cell shape, shrinkage, nuclear fragmentation, and chromatin condensation compared to the uniformly blue stained nuclei observed in vehicle treated controls (Fig. 7A).

Cytomorphology of HepG2 cells after treatment with 40 and 60 µg/mL of phenolic fraction obtained from Echium arabicum extract. (A) Phase-contrast microscopy showed a decrease in the number of cells after treatment versus untreated cells. Nuclear morphology changes in both control and treated cells assessed by DAPI staining, arrows indicating apoptotic cells. (B): Apoptotic morphology detection by acridine orange-ethidium bromide (AO/EB) fluorescent staining of HepG2 cell line treated with phenolic fraction obtained from E. arabicum extract. Arrows indicate condensed or fragmented chromatin.

3.5 AO/EB staining

HepG2 treated cells, stained with AO and EB, displayed characteristic staining pattern confirming apoptosis induction (Fig. 7B). Viable cell appeared green in color (stained only with AO), whilst cell with disrupted cell membrane appeared yellow to orange with condensed chromatin, depending upon the stage of apoptosis (Liu et al., 2015).

3.6 Caspase-3/7 activity assay

Activation of caspase-3/7 resulted in the cleavage of DEVD peptide which enabled the dye to bind to DNA and produce a bright green fluorescence response. The treated cells (Fig. 8) showed an increase in the Caspase-3/7 activity after 24 h of exposure to phenolic fraction.

Effect of phenolic fraction of Echium arabicum on caspase-3 and 7 Activation in HepG2 cells. Cells treated with vehicle and 40 μg/mL for 24 h. Activated caspase-3/7 was visualized by fluorescence microscopy.

3.7 Cell cycle phase distribution

Muse cell analysis of HepG2 treated cells, stained with Muse Cell Cycle Kit, revealed changes in cell distribution in S and G0/G1 phases. Cell population in S-phase increased significantly (P < 0.05) and thereby S-phase arrest, accompanied by a significant decrease in the G0/G1 (Fig. 9). The percentage of cells in S-phase was significantly increased from 26 % in control to 31.3 % (40 μg/mL) and 48% (60 μg/mL) by phenolic fraction treatment.

Effect of phenolic fraction of Echium arabicum on cell cycle distribution in HepG2 cell lines. Cells were treated for 24 h with phenolic fraction at 40 and 60 μg/mL. Analysis of cell distribution is shown by histograms. The experiments were conducted in triplicate. Phenolic fraction induced S-phase arrest in HepG2 cells. T- test was used to determine difference between the control and treated group. The difference was considered significant at P < 0.05.

4 Discussion

One of the advantages of this study was that we assessed the E. arabicum extract using different methods of extraction since each method possesses certain strength and limitation (Azwanida, 2015). In addition, The present investigation reveals for the first time the apoptotic activity of E. arabicum extract.

The search for novel anticancer agents without side effects led to continuous search for new candidates from different sources and mainly through use of ethnomedicinal plants that contributed a lot towards cancer research (Fridlender et al., 2015). Some of compounds isolated were berberine, evodiamine, matrine, piperine, sanguinarine, and tetrandrine, hydroxycinnamates, hydroxybenzoates, coumarins, (Liu et al., 2015). Plant’s phenols are important compounds due to their radical scavenging activity accredited to their hydroxyl groups. They directly contribute to the anti-oxidative (Pan et al., 2008) anti-allergic, anticancer, antiviral, and antimicrobial activities (Nunes et al., 2012). Phenols are used in food industry because they prolong the shelf-life, lower the health risk disorders, and preserve food quality (Shahidi and Ambigaipalan, 2015).

DPPH is a widely used technique for assessing free radical-scavenging activity of compounds. In the present work, the phenolic fraction exhibited concentration -dependent free radical scavenging activity. However, the phenolic fraction (EC50: 594.7 ± 0.02 μg mL − 1) was not as effective as the standard, gallic acid (EC50: 81.2 μg mL − 1). The antioxidant results of the present study were in accordance with the previously published work by Shahat et al. (Shahat et al., 2015). Therefore, the antioxidant activity observed might be due to the phenolic acids and flavonoids capable of donating hydrogen by shifting a single electron to OH·- and O2· radicals (Panche et al., 2016). Linear regression analysis showed that TPC contributes of radical scavenging activity. Overall, this correlation confirm that phenols are the main compounds contributing to the antioxidant potential of the phenol fraction. It is also likely that a synergistic effect among the compounds led to the rise of total antioxidant of the extract. This result is consistent with previous reports that have showed a linear correlation between TPC and the herbal extracts antioxidant capacity reduction (Wojdyło et al., 2007).

Only the phenolic fraction of 6 different fractions studied of E. arabicum displayed cytotoxic effects on human colon (HCT-116 and LoVo) and liver (HuH-7, and HepG2) cancer cell lines. The percent viability of all other fractions tested were higher than 90% (data not shown) at the highest concentration tested. Our result was further confirmed using LDH assay. The LDH release increased significantly with increasing concentrations post treatment of HepG2 cell with phenol fractions of E. arabicum indicating membrane integrity loss and cell death (Rouhollahi et al., 2015). NO is a signaling molecule that regulates different physiological and pathophysiological processes. Treatment of HepG2 cells resulted in a significant NO production. Increased NO production has been reported in cancer cells treated with various anticancer agents (Bani‐Sacchi et al., 1995) and plant extracts that resulted in apoptosis correlated with the production of NO and DNA fragmentation (Kumar and Kashyap, 2015). Reports also revealed that NO can inhibit metastasis and tumor progression (Fukumura et al., 2006). NO• has been considered to be a physiological modulator of cell proliferation, capable of promoting cell cycle arrest (Villalobo, 2006). However, many studies have shown that NO• arrests the cell cycle progression in different phases of different cancer cell types (Huguenin et al., 2004).

The search for anticancer drugs without severe toxicity from ethnomedicinal plants continue to contribute significantly towards cancer cure (Soumya et al., 2021). Interestingly, phenolic fraction did not cause high cytotoxicity on normal liver cells (Chang) viability. These findings are in consistent with previous reports in which plants showed selective cytotoxicity against cancer cells (Tang et al., 2010). This selective cytotoxicity is an important criterion in anticancer drug development because at present most of the available drugs target both normal as well as cancer cells and possess side effects.

Cell cycle control the life of the cells in which the latter is controlled by different regulators such as tumor suppressor genes, cyclin-dependent kinases and their inhibitors thus the abnormality in the cell cycle may lead to DNA damage and apoptosis (Vermeulen et al., 2003). Phenolic fraction arrested the cell cycle of HepG2 at S-phase, indicating that they might have affected synthesis of DNA, preventing the advancement of cell cycle at S-phase and causing apoptosis due to inhibition of cdc25 or DNA Topoisomerase II enzymes which leads to caspases activation (Puri et al., 2004). There are several reports of polyphenol from different plants that reported to arrest the cell cycle at S-phase using different cancer cell lines through the cyclin A, cyclin D1, CDK4, and CDK6 and CDK2 (Lee et al., 2020). Caspase-3/7 activities were detected 24 h post phenolic fraction exposure. Activation of caspase-3/7 in HepG2 cells results in subsequent DNA fragmentation, which is one of apoptosis features. In addition, activation of these caspases after treatments with the phenolic fraction was further confirmed with DAPI and AO/EB dual staining. Hence, the cytotoxic effects of phenolic fraction on HepG2 cells was mediated via apoptosis through caspase-3/7 activations and this could be attributed to the presence of phenolic compounds that has been reported to induce apoptosis through caspase activation (Ji et al., 2009). A prior studies reported that cinnamic acid and protocatechuic acid caused the induction of caspase-9 (de Oliveira Niero and Machado-Santelli, 2013)) in cancer cells. Ferulic acid induce apoptosis by upregulating Bax and downregulating Bcl-2 (Elmore, 2007). Similarly, p-coumaric acid caused cell cycle arrest at subG1 phase and showed different signs of apoptosis such as shrinkage and membrane blebbing (Jaganathan et al., 2013). Likewise, caffeic acid induced apoptosis in fibrosarcoma (Prasad et al., 2011).

5 Conclusions

This study also reports for the first time that the phenolic fraction was cytotoxic to cancer cells through undergoing apoptotic cell death. Even though the underlying mechanisms of the phenolic fraction against HepG2 cancer cells still needs to be investigated, our findings have shown that it exerts its effect through cell cycle modulation and activation of apoptosis via caspases. Additionally, purification of the phenolic fraction and determination of the apoptosis pathway are required to understand the mode of action.

Acknowledgments

Researchers Supporting Project number (RSP-2021/112), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Antiviral activity of borage (Echium amoenum) Archiv. Med. Sci.: AMS. 2010;6(3):366.

- [Google Scholar]

- Apoptotic potential and chemical composition of Jordanian propolis extract against different cancer cell lines. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol.. 2020;30(6):893-902.

- [Google Scholar]

- An overview on the role of dietary phenolics for the treatment of cancers. Nutr. J.. 2016;15(1):1-16.

- [Google Scholar]

- A review on the extraction methods use in medicinal plants, principle, strength and limitation. Med. Aromat. Plants. 2015;4(196):2167-2412.

- [Google Scholar]

- Relaxin-induced increased coronary flow through stimulation of nitric oxide production. Br. J. Pharmacol.. 1995;116(1):1589-1594.

- [Google Scholar]

- Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin.. 2018;68(6):394-424.

- [Google Scholar]

- Global trends in incidence rates of primary adult liver cancers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Oncol.. 2020;10

- [Google Scholar]

- Cinnamic acid induces apoptotic cell death and cytoskeleton disruption in human melanoma cells. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res.. 2013;32(1):1-14.

- [Google Scholar]

- Apoptosis: a review of programmed cell death. Toxicol. Pathol.. 2007;35(4):495-516.

- [Google Scholar]

- Plant derived substances with anti-cancer activity: from folklore to practice. Front. Plant Sci.. 2015;6:799.

- [Google Scholar]

- The role of nitric oxide in tumour progression. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2006;6(7):521-534.

- [Google Scholar]

- Statistical analysis of the relationship between antioxidant activity and the structure of flavonoid compounds. Rev. Chim.. 2019;70(9):3103-3107.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nitrosulindac (NCX 1102): A new nitric oxide-donating non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NO-NSAID), inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis in human prostatic epithelial cell lines. Prostate. 2004;61(2):132-141.

- [Google Scholar]

- Events associated with apoptotic effect of p-Coumaric acid in HCT-15 colon cancer cells. World J. Gastroenterol.: WJG. 2013;19(43):7726.

- [Google Scholar]

- Gallic acid induces apoptosis via caspase-3 and mitochondrion-dependent pathways in vitro and suppresses lung xenograft tumor growth in vivo. J. Agric. Food. Chem.. 2009;57(16):7596-7604.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytotoxicity, mode of action and antibacterial activities of selected Saudi Arabian medicinal plants. BMC complementary and alternative medicine. 2013;13(1):1-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antiproliferative activity and nitric oxide production of a methanolic extract of Fraxinus micrantha on Michigan Cancer Foundation-7 mammalian breast carcinoma cell line. J. Int. Ethnopharmacol.. 2015;4(2):109.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anticancer activity of a novel high phenolic sorghum bran in human colon cancer cells. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longevity. 2020;2020:1-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- An overview of plant phenolic compounds and their importance in human nutrition and management of type 2 diabetes. Molecules. 2016;21(10):1374.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Dual AO/EB staining to detect apoptosis in osteosarcoma cells compared with flow cytometry. Med. Sci. Monit. Basic Res.. 2015;21:15.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antioxidant compounds, antioxidant activity and phenolic content in peel from three tropical fruits from Yucatan, Mexico. Food Chem.. 2015;166:17-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biological oxidations and antioxidant activity of natural products. New York: INTECH Open Access Publisher; 2012.

- Antioxidant activity of microwave-assisted extract of longan (Dimocarpus Longan Lour.) peel. Food Chem.. 2008;106(3):1264-1270.

- [Google Scholar]

- Drug resistance in colorectal cancer: General aspects, Drug Resistance in Colorectal Cancer: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Strategies. Elsevier; 2020. p. :1-33.

- Inhibitory effect of caffeic acid on cancer cell proliferation by oxidative mechanism in human HT-1080 fibrosarcoma cell line. Mol. Cell. Biochem.. 2011;349(1-2):11-19.

- [Google Scholar]

- Telomere-based DNA damage responses: a new approach to melanoma. FASEB J.. 2004;18(12):1373-1381.

- [Google Scholar]

- Inhibitory effect of Curcuma purpurascens BI. rhizome on HT-29 colon cancer cells through mitochondrial-dependent apoptosis pathway. BMC Compl. Alternat. Med.. 2015;15(1)

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chemically diverse and biologically active secondary metabolites from marine Phylum chlorophyta. Mar. Drugs. 2020;18(10):493.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Shahat, A.A., Ibrahim, A.Y., Alsaid, M.S., 2015. Antioxidant capacity and polyphenolic content of seven Saudi Arabian medicinal herbs traditionally used in Saudi Arabia.

- Phenolics and polyphenolics in foods, beverages and spices: Antioxidant activity and health effects–A review. J. Funct. Foods. 2015;18:820-897.

- [Google Scholar]

- Overview of the anticancer activity of withaferin A, an active constituent of the Indian ginseng Withania somnifera. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res.. 2020;27(21):26025-26035.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anticancer potential of rhizome extract and a labdane diterpenoid from Curcuma mutabilis plant endemic to Western Ghats of India. Sci. Rep.. 2021;11(1):1-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phyllanthus spp. induces selective growth inhibition of PC-3 and MeWo human cancer cells through modulation of cell cycle and induction of apoptosis. PloS One. 2010;5(9):e12644.

- [Google Scholar]

- Treatment of liver metastases of colorectal cancer Ann Oncol 2005; 16 Suppl 2: ii144-ii149. Ann. Oncol.: Off. J. Eur. Soc. Med. Oncol.. 2006;17(4):727.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antioxidant activity and phenolic compounds in 32 selected herbs. Food Chem.. 2007;105(3):940-949.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phenolic extract from oleaster (Olea europaea var. Sylvestris) leaves reduces colon cancer growth and induces caspase-dependent apoptosis in colon cancer cells via the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway. PloS One. 2017;12(2):e0170823.

- [Google Scholar]