Translate this page into:

Proposition of an appropriate technique to diagnose catheters fungal infectivities

⁎Corresponding author at: Laboratory: Antifungal Antibiotic, Physico-Chemical Synthesis and Biological Activity, University of Tlemcen, Algeria. seddiki.med@gmail.com (Sidi Mohammed Lahbib Seddiki)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Despite their great importance in the hospital environment, catheters are medical devices that can harm patients following their alterations by bacteria and/or fungal microorganisms. These alterations are classified into three types of infectivities, which may be simple contaminations/colonizations or serious infections. Bacterial infectivities were well studied using the technique of (Brun-Buisson et al., 1987); however, no technique was designed for yeast. Thus, we aimed to adapt the bacterial technique toward the assessment of the fungal infectivities. In order to check its reproducibility, both techniques were used in parallel. The results obtained were not consistent. That of Brun-Buisson et al. reflected more the catheters fungal contamination or colonization; nevertheless, the modified technique was better appropriate to the fungal infections of catheters considering the reduced time for its realization.

Keywords

Fungal infectivities

Candida sp.

Catheters

Diagnostic

Technical

1 Introduction

The scourge of nosocomial infections is a real public health problem due to its epidemiological frequency and its socio-economic cost (Fki et al., 2008). Moreover, there is considerable evidence of an increase in fungal infections acquired in hospitals, including candidiasis in immune-compromised patients with an implanted catheter (Martin et al., 2003; Patterson, 2007; Luzzati et al., 2005; Miceli et al., 2011). These infections can occur at any time when using these devices. Indeed, the strong use of catheters accentuates the exposure of patients to the risks of nosocomial candidiasis (Carrière and Marchandin, 2001) whatever is the type of their material or the pathology that required its implantation (Mermel et al., 2001; Kojic and Darouiche, 2004). On the other hand, it has been described that the diagnosis of catheter-related candidemia is difficult to prove before the removal of the catheter, especially when Candida sp. forms a biofilm on its surface (Gallien et al., 2007). Furthermore, biofilms constitute a potential source of microorganisms endowed with properties of resistance to antifungal agents (Chandra et al., 2008; Espinasse et al., 2010). Thus, (Brun-Buisson, 1994) suggests that it is imperative to distinguish the infection of the catheter from its simple colonization or contamination. In the same context, we prescribed the term infectivity of catheters to reveal the degree of infectiveness of these devices (Seddiki et al., 2013), which may help clinicians in their decision to initiate antifungal therapy. The classification of the catheters’ infectivities is determined by the presence or the absence of local and/or general clinical manifestations (local signs, infectious syndrome) and by their comparison with the qualitative results with regard to possible presence of microorganisms on the internal and/or external surface of the catheter (Carrière and Marchandin, 2001; Mimoz et al., 2007; Ryan et al., 1974). Whatever the clinical data is, the only way to assert catheter infection is to remove it and put it into culture. Thus, the positivity of the culture of the distal end of the catheter relative to the threshold of significance allows the establishment of this classification (Carrière and Marchandin, 2001; Merrer, 2005). It is nevertheless important to recall that the threshold of 15 colony-forming units (CFU) with the semi-quantitative technique of (Maki et al., 1977) was criticized by several authors (Snydman et al., 1982; Rello, et al., 1991; Moyer et al., 1983; Hilton et al., 1988). They reproach him with his lack of sensitivity knowing that this method explores only the external face of the catheter. On the other hand, this threshold value is 103 CFU/mL with the quantitative technique of (Brun-Buisson et al., 1987), which examines the internal and external faces of the catheter. However, these two techniques are usually recognized for the evaluation of bacterial infectivities. Owing to this, we aimed to assess the productivity of the yeast-adapted technique by examining the correlation between fungal infectivities results obtained using both techniques.

2 Material and methods

2.1 Sampling

Samples were collected for two months in three different hospitals in Tlemcen, Algeria. According to the recommendations of the literature (Gürcüoglu et al., 2010; Quinet, 2006), catheters implanted for 48 h and more were instantly collected after their removal from the patients. For this, their distal ends were cut using a sterile chisel and then placed in tubes containing 1 mL of sterile physiological solution. To avoid contamination, the tubes were opened nearby the flame of a torch and then quickly closed. Subsequently, the samples were transported to the laboratory in a cooled bag.

2.2 Identification of fungal strains

The fungal strains isolated from the catheters were purified and then identified by micro-culture series techniques and biochemical identification galleries (API 20 C AUX, Biomerieux, France)

2.3 Evaluation of different types of fungal infectivities

In order to assess the fungal infectivities of the catheters, the method of (Brun-Buisson et al., 1987) and the one modified by our team were used at the same time. The first one consists in carrying out a culture of the sample on agar, and the results were then evaluated by an enumeration of CFU/mL. The second was based on a direct enumeration of yeasts using a hematometer (Thoma blade) and then, the results were reported in cells/mL.

Briefly, the sampling tubes were first vortexing for one minute, this operation makes it possible to detach the yeasts adhered to the walls of the catheters and to examine both their internal and external faces (Brun-Buisson et al., 1987; Boucherit-Atmani et al., 2011). Then, 10 μL were taken with a micropipette from each tube. Petri dishes previously prepared with a Sabouraud agar supplemented with 50 μg/mL of chloramphenicol were inoculated by spreading with a rake. The addition of chloramphenicol (Bio-Rad, France) allows the inhibition of bacteria. The dishes were then incubated at 37 °C for 24 h up to 5 days and the count of the colonies appearing on the agar was reported in CFUs/mL. The experiment was performed twice for each sample.

In parallel, the counting of the yeast cells was carried out (three replicates) using the Thoma blades by the deposition of a volume of the specimen between the blade and the coverslip. The cells count was then carried out under an optical microscope (Magnification ×400) and was reported in cells/mL. Only yeasts within the lines delineating the surface of the Thoma blade were counted (Gognies and Belarbi, 2010).

As previously described, the different types of fungal infectivities of the catheters (infection, colonization and contamination) were evaluated taking into account the threshold of significance (103 CFU/mL or cells/mL) and the clinical data recorded during the sampling (clinical signs of infection). In order to situate the results in their epidemiological context, a statistical analysis of the variance was carried out via GenStat Discovery 3 software (VSN International). The threshold of significance: α = 0.01.

This study was complemented by taking pictures of the view field of the optical microscope during the counting of the yeast cells. In addition, some catheter segments were examined using field emission scanning electron microscopy (Hitachi S-4800, Japan).

3 Results and discussion

During the study period, 399 catheters were taken from 374 inpatients. Some patients had two or more catheter types at the same time. The identification of isolated yeasts revealed 42 strains of Candida distributed among the following species: Candida albicans, C. glabrata, C. parapsilosis, C. guilliermondii, C. famata, C. tropicalis, C. krusei and C. kefyr. The involvement of each species in relation to catheter type, patient clinical data, admissions services and hospital structures was variable (unpublished data). Many studies have shown that C. albicans are the most involved in fungal infections related to catheters use (Boucherit-Atmani et al., 2011; Beck-Sague and Jarvis, 1993; Dekeyser et al., 2003; Phan et al., 2007; Pereira and Maisch, 2012). However, the isolation of non-albicans Candida species from medical devices was constantly increasing; this indicates the non-negligible importance of these species in fungal pathology (Dekeyser et al., 2003; Dupont, 2007; Trofa et al., 2008; Miceli et al., 2011; Taieb et al., 2011; Seddiki et al., 2015). Overall, regardless of the species involved, contamination was the dominant type of infectivity, followed by colonization and then infections. It has been postponed that colonizations present an epidemiological interest but have no clinical relevance (Rijnders et al., 2002). Despite this, it may progress to a serious infection.

According to our results, variability was observed according to the method used. 86.22% (344) of the samples did not reveal the presence of any colony or cell using either of the two methods cited above. On the contrary, when either method did not reveal any CFU or fungal cell (4.26% of all cases), the other method showed at least one CFU or cell and vice versa. On the other hand, in only 1% of cases, the count of CFUs according to the Brun-Buisson method was difficult to determine given their large number in the same Petri dish.

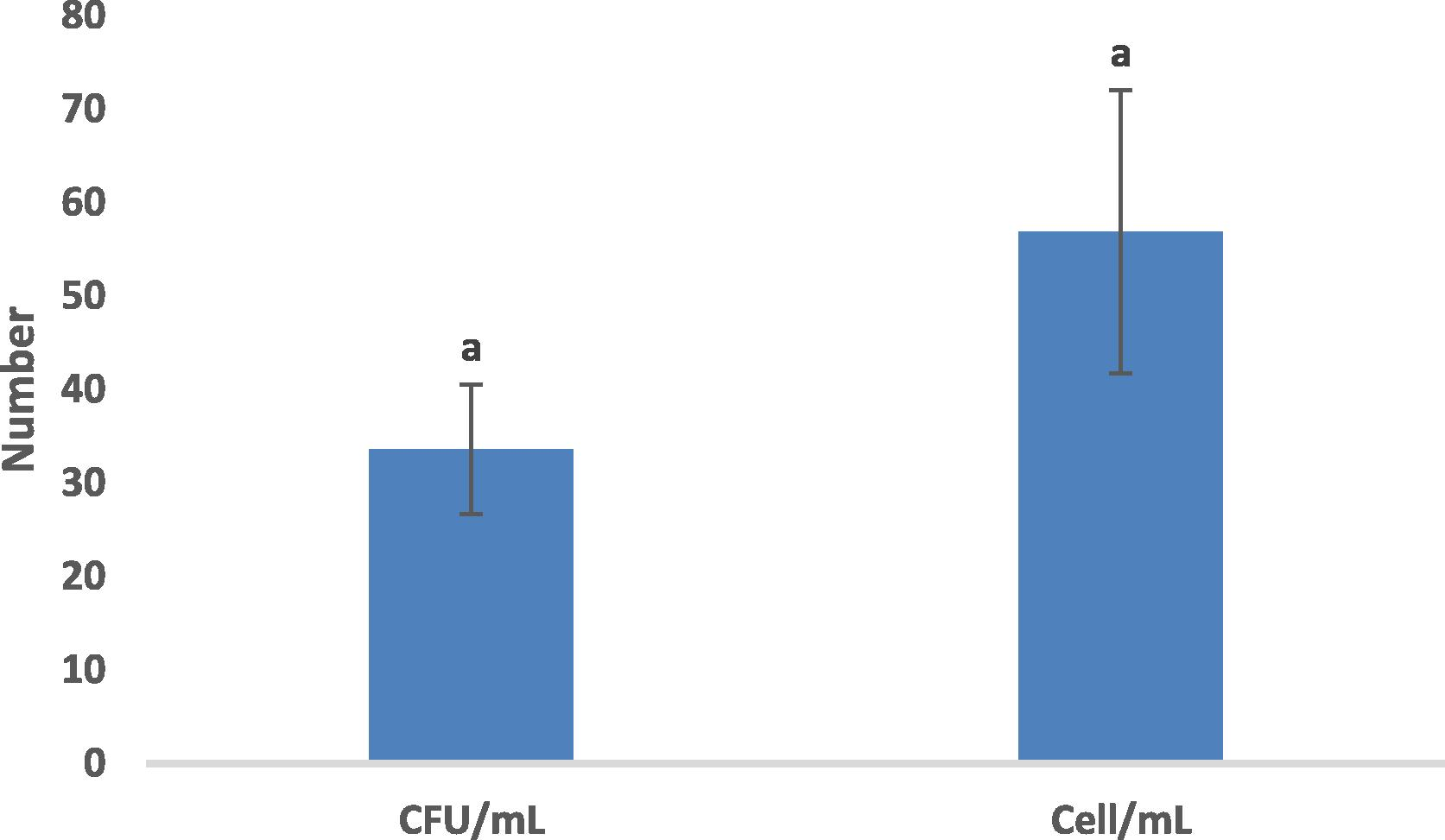

Moreover, all the other results were proved to be positive with both methods despite their divergence in many cases. In addition, according to the analysis of the variance, these results showed a non-significant difference (P-value = 0.166) between the number of CFUs/mL and the number of cells /mL.

Fig. 1 illustrates the dissimilarity between the two methods of enumeration used.

Comparison of two methods of enumeration. Vertical bars indicate standard errors of average. Bars with the same letters (a) indicate a non-significant difference between the means according to the Duncan test of means of separation with a significance level of 0,01.

These results can be explained partly by the fact that the technique of (Brun-Buisson et al., 1987) expresses the number of CFUs/mL after vortexing of the sample for one minute; but the yeast-modified technique expresses the number of cells that exists in one milliliter of the sample (Seddiki et al., 2013). These results may also be due to the non-viability of some yeast cells at the time of their culture, which leads to a negative result by the technique of Brun-Buisson; although their quantification is possible under an optical microscope. In contrast, some yeast cells could be dormant and therefore diminished their sizes (Boucherit et al., 2007) with partial deformation and changes in their cell surfaces (Benmansour et al., 2014) which diverts their counting under the microscope using a hematometer.

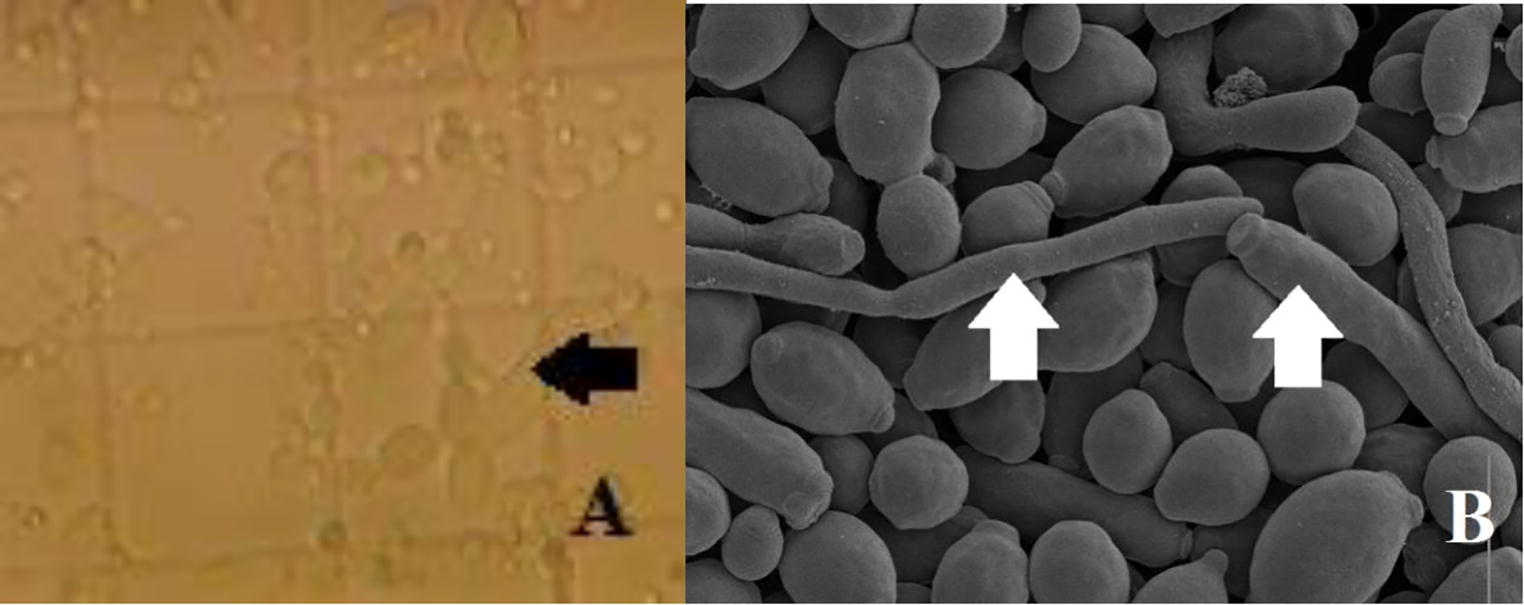

On the other hand, microscopic observation revealed, in many cases, the formation of hyphae and pseudohyphae by some species (Fig. 2A). These structures drastically impeded the counting of yeasts in their blastospore form. Indeed, electronic imaging of a sample vortexed for one minute distinctly showed yeast cells of Candida sp. with bud scars in addition to hyphal and pseudohyphal structures; many yeast however, appeared shrunken (Fig. 2B). Remarkably, those structures were particularly observed in the cases of catheters infections.

Microscopic observation of: (A) optical microscope after vortexing samples for one minute, (B) scanning electron microscope. Arrows indicate hyphae and pseudohyphs (Magnification, A: ×400, B: ×5000).

By observing the two preceding figures, three structural shapes may be present at the same time on the same catheter. In addition, blastospore (yeast cell) cannot be confused with other forms, which leads to think that other factors, like biofilm formation, may have further possible influence. All the same, microscopic techniques lead to a re-evaluation of these. In a study published in 2011, Boucherit-Atmani et al., were noted that vortexing of the catheters for one minute does not allow all the yeasts to be detached. Additionally, another report of examination of the catheters shows, in many cases, the existence of biofilms, while the cultures of the same catheters would be negative or below the predefined threshold (Brun-Buisson, 1994). Otherwise, according to our knowledge, there is little data in the literature explaining the fungal microbial load causing infection. As well, one case of catheter infection was attributed to C. albicans with only 102 CFUs /mL (Brun-Buisson et al., 1987).

4 Conclusion

It is difficult to establish correlations between the two methods used in our study. Our modified method expresses the number of yeast cells detached after vortexing for one minute, whereas that of (Brun-Buisson et al., 1987) expresses the number of still viable cells which can give colonies following their cultivation. The results obtained suggest that the modified method by our team is better qualified to disclose catheter fungal infections since clinicians may have the result in record time (within few minutes). On the other hand, that of (Brun-Buisson et al., 1987) mainly reflects the evolution of contamination or colonization of catheters towards possible infections. Therefore, the simultaneous use of both techniques may be the best way to provide the clinician with useful information to guide his/her practical attitude towards establishing an antifungal treatment or not.

5 Formatting of funding sources

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to express their heartfelt thanks to Asma Kebiri, English teacher at the University Center of Naâma, for her kindness of reviewing the article. We also want to thank the staff of the University Hospital of Tlemcen, the Hospital “Chaâbane Hamdoune” of Maghnia and the Hospital of Nedroma (Algeria).

References

- Fki, H., Yaïch, S.J., Didi, J., Karray, A., Kassis, M., Damak, J., 2008. Epidémiologie des infections nosocomiales dans les hôpitaux universitaires de Sfax: Résultats de la première enquête nationale de prévalence de l’infection nosocomiale. revue tunisienne d’infectiologie 2, 22–31.

- The epidemiology of sepsis in the United States from 1979 through 2000. N. Engl. J. Med.. 2003;348:1546-1554.

- [Google Scholar]

- Treatment and prevention of fungal infections. Focus on candidemia. New York: Applied Clinical Education; 2007. p. :VII-VIII.

- Secular trends in nosocomial candidaemia in non-neutropenic patients in an Italian tertiary hospital. Clin. Microbiol. Infect.. 2005;1:908-913.

- [Google Scholar]

- Infections liées aux cathéters veineux centraux : diagnostic et définitions. Néphrologie. 2001;22:433-437.

- [Google Scholar]

- Guidelines for the management of intravascular catheter- related infections. Clin. Infect. Dis.. 2001;32:1249-1272.

- [Google Scholar]

- Traitement des candidémies chez un patient porteur d’un cathéter vasculaire. J. Mycol. Med.. 2007;17:42-44.

- [Google Scholar]

- Risques infectieux associés aux dispositifs médicaux invasifs. Rev. Franco Lab.. 2010;426:51-63.

- [Google Scholar]

- Brun-Buisson, C., 1994. analyse critique des méthodes diagnostiques d'infection liée au cathéter sur matériel enlevé. Réan. Urg. 3 (3 bis) 343–346.

- Assessment of the types of catheter infectivity caused by Candida species and their biofilm formation. First study in an intensive care unit in Algeria. Int. J. Gen. Med.. 2013;6:1-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chlorhexidine-based antiseptic solution vs. alcohol-based povidone-iodine for central venous catheter care. Arch. Intern. Med.. 2007;167:2066-2072.

- [Google Scholar]

- Catheter complications in total parenteral nutrition. A prospective study of 200 consecutive patients. N. Engl. J. Med.. 1974;290:757-761.

- [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiology of catheter-related infections in intensive care unit. Ann. Fr. Anesth. Reanim.. 2005;24:278-281.

- [Google Scholar]

- A semi quantitative culture method for identification of catheter-related infection in the burn patient. J. Surg. Res.. 1977;22:513-520.

- [Google Scholar]

- Predictive value of surveillance skin cultures in total parenteral nutrition-related infections. Secular trends in the epidemiology of nosocomial fungal infections in the United States. J. Infect. Dis.. 1982;167:1247-1251.

- [Google Scholar]

- Laboratory diagnosis of catheter-related bacteremia. Scand. J. Infect. Dis.. 1991;23:583-588.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparative culture methods on 101 intravenous catheters. Routine, semiquantitative, and blood cultures. Arch. Intern. Med.. 1983;143:66-69.

- [Google Scholar]

- Central catheter infections: single- versus triple-lumen catheters Influence of guide wires on infection rates when used for replacement of catheters. Am. J. Med.. 1988;84:667-672.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnosis of central venous catheter-related sepsis: critical level of quantitative tip cultures. Arch. Intern. Med.. 1987;147:873-877.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nosocomial candidemia in adults: Risk and prognostic factors. J. Mycol. Med.. 2010;20:269-278.

- [Google Scholar]

- Abord veineux de longue durée: épidémiologie, diagnostic, prévention et traitement des complications infectieuses: Abord veineux de longue durée. Archives de pédiatrie. 2006;13:714-720.

- [Google Scholar]

- Candida albicans biofilms formed into catheters and probes and their resistance to amphotericin B. J. Mycol. Med.. 2011;21:182-187.

- [Google Scholar]

- Use of a new gelling agent (Eladium©) as an alternative to agar-agar and its adaptation to screen biofilm-forming yeasts. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol.. 2010;88:1095-1102.

- [Google Scholar]

- Secular trends in the epidemiology of nosocomial fungal infections in the United States, 1980–1990. National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance System. J. Infect. Dis.. 1993;167:1247-1251.

- [Google Scholar]

- Candidémiea Candida utilis chez un patient de réanimation résistant au traitement par fluconazole. Médecine et maladies infectieuses.. 2003;33:221-223.

- [Google Scholar]

- Als3 is a Candida albicans invasin that binds to cadherins and induces endocytosis by host cells. PLoS Biol.. 2007;5:e64.

- [Google Scholar]

- Photodynamic inactivation for controlling Candida albicans. Fung. Biol.. 2012;116:1-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Dupont, H., 2007. Levures en réanimation, 49ème Congrès de la Société Française d’Anesthésie-Réanimation. Ed. SFAR. Paris, Elsevier, pp. 415–432.

- Candida parapsilosis, an emerging fungal pathogen. Clin. Microbiol. Rev.. 2008;21:606-625.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prise en charge des infections systémiques à Candida spp. La Revue de médecine interne.. 2011;32:173-180.

- [Google Scholar]

- Infectivités fongiques des cathéters implantés dues à Candida sp. Formation des biofilms et résistance. J. Mycol. Med.. 2015;25:130-135.

- [Google Scholar]

- Catheter-tip colonization as a surrogate end point in clinical studies on catheter-related blood stream infection: how strong is the evidence? Clin. Infect. Dis.. 2002;35:1053-1058.

- [Google Scholar]

- Dormancy of Candida albicans cells in the presence of the polyene antibiotic amphotericin B: simple demonstration by flow cytometry. Med. Mycol.. 2007;45:525-533.

- [Google Scholar]

- Dormancy of Candida albicans ATCC10231 in the presence of amphotericin B. Investigation using the scanning electron microscope (SEM) J. Mycol. Med.. 2014;24:e93-100.

- [Google Scholar]