Translate this page into:

Profiling of phytochemical constituents of terminalia chebula fruit extract by different solvent effects and synchronized analysis of FTIR and GCMS

⁎Corresponding author at: Department of Biochemistry, College of Sciences, King Saud University, P.O.Box 2455, Riyadh 11451, Saudi Arabia. mfbadr@ksu.edu.sa (Mohamed Farouk Elsadek),

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background

Detecting the Teminalia chebula best extract-enriching bioactive compounds using four different solvents; Ethanol, water, chloroform and petroleum ether for medicinal applications.

Methods

Qualitative analysis of phytochemicals of T. chebula (such as Tannins, saponins, flavonoids, alkaloids, terpenoids); Quantitative Determinations (Condensed tannins; total flavonoids, and phenolics), also, determination of enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidants. GC–MS and FT-IR analysis of ethanolic extract were investigated.

Results

The assays for phenolics, tannins and total flavonoids indicated an extensive difference in the total phenolic content ranging from 26 to 104, 13 to106 and 106 µg/g of extract. It was found that, the highest phenolics, tannins and total flavonoids content were found in the ethanolic extract and the lowest by petroleum ether extract. In examining the amount of total protein content also, high amount of total proteins observed in the ethanolic extract as 67 µg/g whereas, in contrast, the high amount of total carbohydrates observed in the aqueous extract with 103 µg/g. Further, the level of the different enzymatic antioxidant markers (SOD, Catalase and Gpx) and non-enzymatic antioxidant markers (vitamin C and vitamin E) produced by the ethanolic T. chebula fruit extract were 0.46 µg, 97 µg and 127 µg and 39.08 µg and18 mg/liter. The DPPH and reducing power assay radical scavenging activities of different solvent extracts of T. Chebula exhibited free radical scavenging properties up to 96 % of inhibition. The functional groups of the components were separated based on its peaks through FTIR analysis showed the existence of alcohol, alkanes, carboxylic acid, alkenes, alkanes, ethers, halogen respectively. The active compounds identified based on GCMS analysis showed the presence of furaldehyde, 2,5-furandicarboxaldehyde Dodecanoic acid, ethylester n-pentadecanol, 1,2,3-Benzenetriol pyrogallol, 3,4,5trihydroxy benzoic acid, Octadecanoicacid,ethyl ester and Hentriacontane.

Conclusion

Among four solvent screened, the ethanol extract of T. chebula revealed variety of bioactive phytochemicals. In addition to higher antioxidant activities and highest level of radical scavenging activity. Accordingly, it can be inferred that T. chebula may serve as an antibacterial, antifungal, anti-inflammatory, and anti-diabetic agent in addition to being a plant-based antioxidant.

Keywords

T. chebula

Phytochemicals

Antioxidants

DPPH

FTIR

GCMS

1 Introduction

Photochemicals are naturally occurring chemicals found mostly in plants, especially vibrant ones. They are abundant in medicinal plants and herbs and function as primary and secondary plant metabolites with anti-inflammatory, anti-microbial, anti-diabetic, and anti-hyperglycemic properties (Saiful Yazan and Armania, 2014). Natural antioxidants mostly comprise plant phenolic components such flavonoids, tocopherols, and phenolic acids. The potential natural source for disease prevention and treatment provided by medicinal plants is mostly due to their secondary metabolites. In order to access these natural chemicals from plant extracts vital for their therapeutic characteristics, many researchers have been drawn to plants (Ali et al., 2008).

Therefore, emphasis has been put on using natural antioxidants, such as bioactive flavonoids, which are crucial because of their native origin and potent capacity to scavenge and trap free radicals. T. chebula has been used extensively in Ayurveda to treat diabetes. In addition, according to Bag et al. (2013), it has been used to treat vomiting, sore throats, coughs, dysentery, diarrhoea, ulcers, bleeding piles, heart, gout, asthma and bladder issues. Vitamin K and calcium, which are essential for blood homeostasis and bone health, are abundant in T. chebula leaves, claimed by Malik et al. (2020). T. chebula fruits are immature, black, ovoid and contain about 20–40 % of tannins, anthraquinones, β-sitosterol, palmitic, oleic and linoleic acids. Bajpai et al. 2005 examined the antioxidant properties of T. chebula and its bioactive component-rich fractions and reported When compared to the leaves and fruits of T. chebula (80.1 0.9 % and 79.8 0.5 %, respectively), the bark exhibits exceptional antioxidant activity (85.2 1.10 %). The phenolic particles in phenolic compounds, which stifle free radicals to prevent oxidative stress, were said to be responsible for this antioxidant effect.

Numerous research teams have thoroughly investigated the antimicrobial, antioxidant, anticarcinogenic, hypocholesterolemic, diuretic, antimicrobial and anti-carcinogenic properties of T. chebula (Cheng et al., 2003; Saleem et al., 2002) These effects of T. chebula include diuretic, antitussive and wound healing. They can also be used as a dentifrice to treat loose gums, ulcers, and gum bleeding, as well as a tonic for hepatic issues, spleen enlargements, and skin conditions (Pouly and Larue, 2007). T. chebula fruit pulp extracts in water ethanolic form demonstrated notable antibacterial activity, antiviral activity at minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC), and minimum bactericidal effects (Bag et al., 2013). Also, T. chebula has been reported to be effective against Alternaria brassicicola, A. alternata, Aspergillus niger, Helminthosporium, Fusarium oxysporum, F. solani and Phytophthora capsica (Mehmood et al., 1999; Shinde et al., 2011). Tayal et al. (2012) showed that T. chebula extract had cyto-protective effects on the MDCK and NRK-52E renal epithelial cells by lowering LDH leak and boosting cell survival. Also, they reported it inhibited calcium oxalate crystal formation in vitro and it is a strong candidate for additional pharmacological studies.

Therefore, the objective of the current study is to assess the phytochemical contents of four extracts from T. chebula with different solvents (Ethanol, Water, Chloroform and Petroleum ether) and their anti-oxidant potential by DPPH and reducing power assay. Also, the level of the different enzymatic antioxidant markers (SOD, Gpx and Catalase) and non-enzymatic antioxidant markers (Vitamin E and C) were screened. Further, these extracts were then Characterized using FTIR and GCMS analysis for identifying the best extract with maximum bioactive compounds could be used in different diseases management.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Plant material collection

Healthy T. chebula fruit was collected from Kanchipuram, Tamil Nadu, India. The plant material was washed and rinsed with 70 % alcohol and sterilized distilled water respectively, dried in air, powdered and the extracts were prepared.

2.2 Preparation of extracts

The plant material was ground into a powder, and the powdered components are utilized to create extracts for usage with water, ethanol, petroleum ether, and chloroform. The extraction of each extract was carried out independently using 150 ml of ethanol, chloroform, petroleum ether, and water for 4 h in the sohxlet apparatus using 10 gm of carefully weighed powdered ingredients. The extract was collected and allowed to dry entirely while evaporating. The dried extract was gathered and used for other analysis.

2.3 Qualitative analysis of phytochemicals of t. Chebula

In order to establish the presence (+) and absence (−) of phytochemicals like tannins, terpenoids, flavonoids, saponins, alkaloids, glycosides, phenol, steroids, amino acids, and proteins, the various solvent extracts of T. chebula fruit underwent a variety of standard qualitative assays. Tannins, saponins, flavonoids, alkaloids, terpenoids, glycosides, proteins, and steroids are among the substances that have been tested qualitatively (Abdullahi, 2013, Banso and Adeyemo, 2006, Roopashree et al., 2008, Joshi et al., 2013, Kancherla et al., 2019).

2.4 Quantitative determination of T.chebula

Condensed tannins were assessed using the butanol-HCl method (Terrill et al., 1992), total flavonoids were assessed using Aiyegoro and Okoh's (2010) methodology, and total phenolics were quantified using Graham's (1992) Prussian blue method in T. chebula fruit extract. Further, the estimate of proteins using Lowry's method (Lowry et al. 1951) and the estimation of carbohydrates using the Anthrone method as per Yemm and Willis (1954) in T. chebula fruit extract.

2.5 Antioxidant analysis of t. Chebula

2.5.1 Determination of enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidants

T. chebula fruit extract was tested for catalase (CAT) activity using the Aebi (1984) method using Spectrophotometer. Glutathione peroxidase (Gpx) activity was evaluated using the method provided by Hafemann et al. (1974) and superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity was tested using the method described by Das et al. (2000). The method of Baker (1988) was used to calculate the concentration of tocopherol (vitamin E-tocopherol), and the method of Omaye et al. (1979) was used to calculate the concentration of ascorbic acid.

2.5.2 DPPH scavenging activity of t. Chebula

Using the methodology described by Shimada et al. (1992), the scavenging capacity of polyphenolic extracts from T. chebula against the 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical was evaluated. Reduced absorbance was seen at 517 nm when 0.1 mM DPPH solution was added to plant extract/ascorbic acid at various doses (20, 40, 60, 80, and 100 g/mL) in the presence of Tris–HCl buffer (50 mM, pH 7.4). The IC50 values of polyphenolic extract were determined and compared with the accepted reference chemical ascorbic acid, using a mixture of methanol and extract as the blank, as indicated by the equation below:

Percent of inhibition = . [(Absorbance of control − Absorbance of test solution)/ Absorbance of control)] x 100.

2.5.3 Ferric reducing antioxidant power of t. Chebula

Spectrophotometric calculations were used to determine the antioxidant content of the T. chebula fruit extract (Ferreira et al., 2007). 1 mL extract of T. chebula fruits with potassium ferricyanide and phosphate buffer (pH 6.6) and incubating it at 50 °C for 20 min at various concentrations (20, 40, 60, 80, and 100 µg/mL). The mixture was centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min after being added TCA (10 %). The supernatant was mixed with FeCl3 (0.1 %), and the absorbance was measured at 700 nm.

2.6 FT-IR analysis of ethanolic extract of t. Chebula fruit

The ethanolic fruit extract of T. chebula was dried at 600 °C in an oven and then crushed into a fine powder. A salt disc (3 mm in diameter) was made by compressing 2 mg of the sample with 100 mg of KBr (FT-IR grade). The disc was retained in the sample holder right away, and FT-IR spectra were taken in the 400 – 4000 cm−1 absorption range using Shimadzu FT-IR spectrometer.

2.7 GC–MS analysis of of ethanolic extract of t. Chebula fruit

Analysis was conducted using Gas Chromatography (Agilent, USA) hyphenated to a high resolution mass spectrometer. Helium was used as the carrier gas at a rate of 1 mL/min. The capillary column used has a 0.25 mm internal diameter. The input temperature was 1000 °C, while the detector was at 2800 °C. The temperature was raised from 1000 °C to 2000 °C (100 °C/min) for two minutes. It was heated to 2800 °C (300 °C/min) for an additional 3 min after being maintained at 2400 °C (100 °C/min) for 3 min. The GC lasted 27 min in total. The % amount of peak area was calculated by comparing the average peak area for each component to the total areas. The mass spectrum from the GC–MS was deciphered, and the chromatogram and mass spectra were evaluated using HPCHEM software and compared with the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) database (contains more than 62,000 patterns).

3 Results

3.1 Phytochemical analysis of t. Chebula

The results obtained from T. chebula fruit extracts using a variety of solvents, including ethanol, chloroform, petroleum ether, and water, showed that the ethanolic and aqueous extract of T. chebula fruit had a good extraction yield of all compounds examined as shown in Table 1. In contrast to the petroleum ether extract, which only revealed the presence of tannins, alkaloids, terpenoids, and phenols whereas the chloroform extract revealed the existence of phenols, flavonoids, alkaloids, glycosides, amino acids and proteins.

S. No.

Phytochemicals

Ethanol extract

Petroleum ether extract

Chloroform extract

Aqueous extract

1

Tannins

++

−

−

++

2

Flavonoids

++

−

+

++

3

Alkaloids

++

+

+

+

4

Terpenoids

++

+

−

+

5

Saponins

++

+

−

++

6

Glycosides

++

−

+

++

7

Phenols

++

+

++

+++

8

Steroids

+

−

−

+

9

Amino acid

+

−

+

++

10

Proteins

+

−

+

+

3.2 Total phenolics, tannins and flavonoids content determination

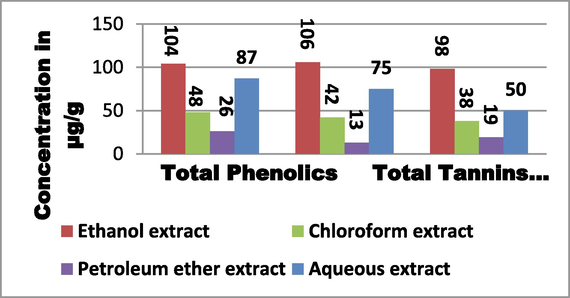

Fig. 1 illustrates the sample concentration of phenolic compounds (µg/g of extract) in various solvent extracts of T. chebula fruit. The phenolic assays revealed a wide range in the total phenolic content of the extracts, ranging from 26 to 104 µg/g. The ethanolic extract has highest phenolic content at 104 µg/g, followed by the aqueous extract at 87 µg/g, the chloroform extract at 48 µg/g, and the petroleum ether extract at 26 µg/g. Tannin concentrations in T. chebula fruit extracts were measured using a variety of solvent types, and the results ranged from 13 to 106 µg/g of extract (Fig. 1). It was found that the ethanolic extract had the highest concentration of tannins (106 µg/g of extract), followed by the aqueous extract (75 µg/g), the chloroform extract (42 µg/g), and the petroleum ether extract (13 µg/g) (Fig. 1). Between 19 and 98 µg/g of extract contained total flavonoids extracted from T. chebula fruit extracts using various solvents. The ethanolic extract had the highest concentration of total flavonoids (98 µg/g), followed by the aqueous extract (50 µg/g), the chloroform extract (38 µg/g), and the petroleum ether extract (19 µg/g).

Total Phenolics, Tannins and Flavonoid content in the fruit extract of T.chebula extracted using different solvents.

3.3 Total protein and carbohydrates content in fruits extract of t. Chebula

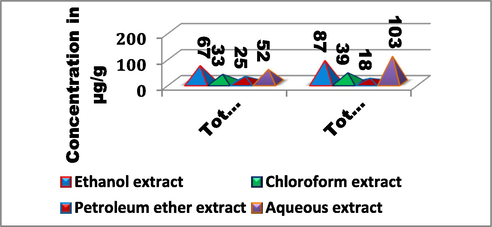

Using different solvents, the total protein concentration in T. chebula fruit extracts ranged from 25 to 67 µg/g of extract. The ethanolic extract had the highest concentration of total proteins (67 µg/g), followed by the aqueous extract (52 µg/g), the chloroform extract (33 µg/g), and the petroleum ether extract (25 µg/g). Utilizing different solvents, the total amount of carbohydrates in T. chebula fruit extracts ranged from 18 to 103 µg/g of extract. Aqueous extract had the highest concentration of total carbohydrates (103 µg/g) followed by ethanolic extract (87 µg/g), chloroform extract, (39 µg/g) and petroleum ether extract (18 µg/g) [Fig. 2]. (Fig. 3.).

Total proteins and carbohydrates content in T. chebula fruit extract.

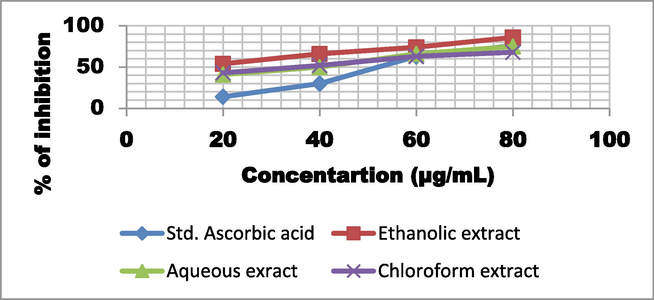

DPPH scavenging activity of T. chebula fruit extract using different solvents.

3.4 Measurement of different enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidant markers

The levels of the various enzymatic (SOD, Catalase and Gpx) and non-enzymatic (Vitamin C and Vitamin E) antioxidant indicators were shown in Table 2. It revealed that the levels of enzymatic antioxidant such as SOD, Catalase, and Gpx were of 0.46 µg of pyrogallol auto-oxidation inhibition/min, 97 µg of hydrogen peroxide utilized/min, and 127 µg of reduced glutathione oxidized/min respectively. The non-enzymatic antioxidant indicators such as vitamins C and E were detected and found to be 39.08 µg /L and 18 µg/L respectively.

S.No.

Parameters

Concentration of antioxidants

Enzymatic antioxidants

1.

Superoxide dismutase

0.46 µg of pyrogallol auto-oxidation inhibition/minute

2.

Catalase

97 µg of hydrogen peroxide utilized/minute

3.

Glutothione peroxidase (Gpx)

127 µg of reduced glutathione oxidized/minute

Non-enzymatic antioxidants

4.

Vitamin C

39.08 µg/litre

5.

Vitamin E

18 mg/litre

3.5 DPPH radical scavenging assay

The DPPH radical scavenging ability of various solvent extracts of T. chebula studied at dosages of 20, 40, 60, 80, and 100 g/ml is shown in Fig. 2. All of the T. chebula solvent extracts evaluated demonstrated free radical scavenging activities, with inhibition ranging from 41 to 96 %. The highest levels of scavenging action were demonstrated by the ethanolic extract of T. chebula at concentrations of 20, 40, 60, 80, and 96 %, respectively. The aqueous extract of T. chebula suppresses free radicals by 41, 50, 66, 75, and 91 % at concentrations of 20, 40, 60, 80, and 100 µg/ml respectively. Furthermore, at doses of 20, 40, 60, 80, and 100 µg/ml, the chloroform fruit extract of T. chebula suppresses free radicals by 43, 52, 50, 63, 68 and 76 %, respectively. The standard reference, ascorbic acid, on the other hand, showed inhibition of 14, 30, 63, 76, and 92 % at various concentrations.

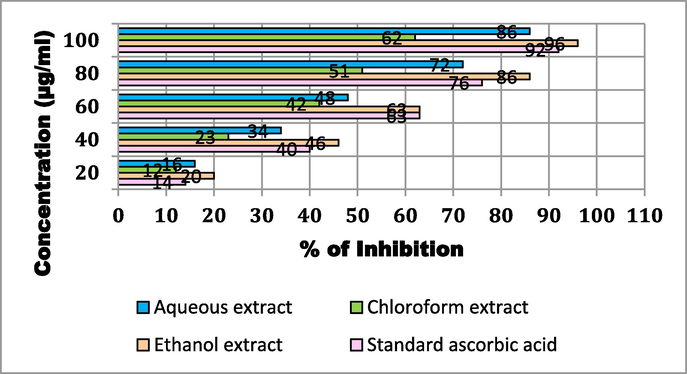

3.6 Ferric reducing power (FRAP) assay of t. Chebula

The results of the reducing power assay for the various solvent extracts of T. chebula investigated in this work (20, 40, 60, 80, and 100 µg/ml) are displayed in Fig. 4. All of the solvent extracts of T. chebula that were tested showed antioxidant activity, with inhibition levels ranging from 12 to 96 %. The ethanolic extract of T. chebula at 20, 40, 60, 80, and 100 µg/ml exhibited the highest antioxidant activity of 20, 46, 63, 86, and 96 % respectively. The concentrations of 20, 40, 60, 80, and 100 µg/ml, the aqueous extract of T. chebula inhibits free radicals by 16, 34, 48, 72, and 86 %, respectively. Furthermore, at concentrations of 20, 40, 60, 80, and 100 µg/ml, the T. chebula, chloroform extract inhibits free radicals by 12, 23, 42, 51 and 62 %, respectively. Ascorbic acid served as the standard control and showed 14, 40, 63, 76 and 92 % inhibition.

FRAP assay of T. chebula fruit extract using different solvents.

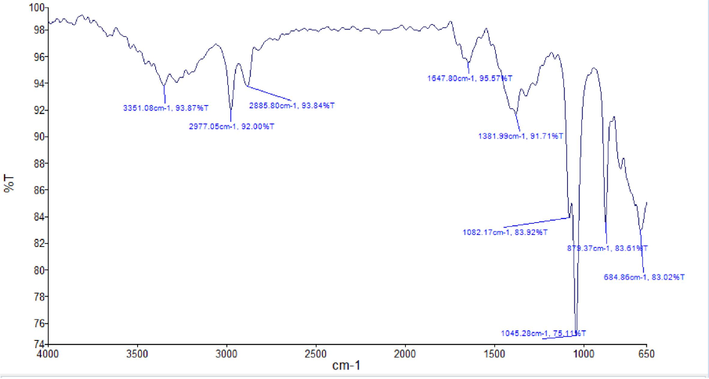

3.7 FTIR analysis

Further, the FTIR analysis was performed on the ethanolic extract that was discovered to be abundant in phytochemicals and to have the highest antioxidant activity. According to their peaks, the functional groups of the constituents were divided (Fig. 5), and Table 3 provides an explanation of the chemical linkages. The distinctive absorption band at 3351.08, 2977.05, 2885.80, 1647.80, 1381.99, 1082.17, 1045.28, 879.37 and 684.86 cm−1 revealed the existence of the following functional groups, namely alcohol, alkanes, carboxylic acid, alkenes, alkanes, ethers, ethers, halogen, and halogen, respectively (Table 3). The respective chemical bonds identified in the study comprise alcohol, alkanes, carboxylic acid, alkenes, ethers, and halogens. They also included C=C stretching, O–H stretching, C–H stretching, C-O stretching, and C-Cl stretching.

FTIR analysis of ethanolic fruit extract of T. chebula.

Peak value

Functional group

Compound

3351.08

–OH group

Alcohol

2977.05

C–H group

Alkanes

2885.80

O–H Stretching

Carboxylic acid

1647.80

C=C group

Alkenes

1381.99

C–H Stretching

Alkanes

1082.17

C-O Stretching

Ethers

1045.28

C-O Stretching

Ethers

879.37

C-Cl Stretching

Halogen

684.86

C-Cl Stretching

Halogen

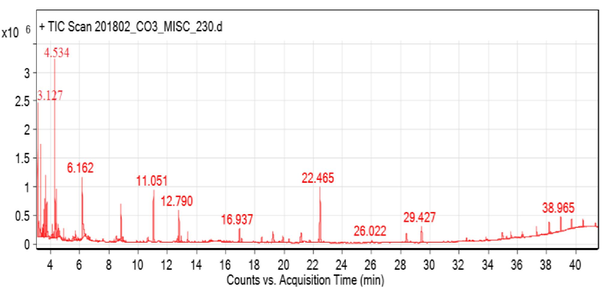

3.8 GCMS analysis

The active principles are outlined in Table 4 and Fig. 5, which demonstrated the presence of nine bioactive phytochemical compounds in the ethanolic fruit extract of T. chebula by using gas chromatography (Fig. 6). The active principles are listed along with their retention time (RT), molecular formula, peak name, nature of the compound, and activity of the compound. Furaldehyde, 2,5-Furandicarboxaldehyde Dodecanoic acid, ethylester n-pentadecanol, 1,2,3-Benzenetriol pyrogallol, 3,4,5-trihydroxy benzoic acid, Octadecanoicacid, ethyl ester, and hentriacontane were the substances identified based on the relative amounts. Aldehydes, phenols, palmitic acid, alcohols, polyphenols, gallic acid, and alkanes are found in T. chebula by GCMS (Table 4).

Retention Time

Peak Name

Formula

Nature of the compound

Activity

3.127

Furaldehyde

C5H4O2

Aldehyde

Antimicrobial

4.534

2,5- Furandicarboxaldehyde

C6H4O5

Aldehyde

Antimicrobial

11.051

2,4 Di-t-butylphenyl

C5H8O4

Phenol

Antineoplastic

12.790

Dodecanoic acid, ethylester

C12H24O2

Palmitic acid

Antimalarial, Antioxidant

16.937

n-Pentadecanol

C15H30O2

Alcohol

Antioxidant

22.465

1,2,3-Benzenetriol pyrogallol

C6H6O3

Poly phenol

Antimicrobial, Anticancer, Antioxidant

26.022

3,4,5 Trihydroxy benzoic acid

C7H6O5

Gallic acid

Antioxidant, Anticancer, Antimicrobial

29.427

Octadecanoicacid, ethyl ester

C18H32O

Aldehyde

Antimicrobial, Anti inflammatory

38.965

Hentriacontane

C31H64

Alkane

Anticancer

GC–MS analysis of phyto-compounds in the ethanolic extract of T. chebula fruit.

4 Discussion

In the current study, the fruit extract from the medicinal plant T. chebula was produced using quite a few solvent extraction techniques and its phytochemical content was tested. The T. chebula fruit extract was subjected to preliminary qualitative phytochemical analysis utilizing a variety of solvents, including ethanol, chloroform, petroleum ether, and water. This analysis identified the presence of tannins, flavonoids, alkaloids, terpenoids, saponins, glycosides, phenol, steroids, amino acids, and proteins. Additionally, it was determined that the ethanolic extract of T. chebula fruit had the highest extraction of all the phytochemicals screened that has been examined followed by the aqueous extract. Congestive heart failure and cardiac arrhythmia have both been treated with phytochemicals known as cardiac glycosides, also, alkaloids exhibit cytotoxicity against leukemia and HeLa cell lines as well as bioactivity against Gram-positive bacteria (Vladimir and Ludmila, 2001).

In our investigation, in general, the total phenolic tannins, and total flavonoids contents ranged from 26 to 104, 13 to 106, and 19 to 98 µg/g of extract respectively. According to the data, the order of efficiency for extracting phenolics, tannins, and total flavonoids is ethanol > aqueous > chloroform > petroleum ether. It has been shown that the polarity of the extraction medium and the solute to solvent ratio appeared to affect a component's ability to be extracted. This study showed that ethanol has greater extractability power than the other solvents utilized, because the range of phenolics, tannins, and total flavonoids are highest in ethanolic extract and lowest in petroleum ether extract. The findings are in line with those of Ao et al. (2008) who found that, when compared to other solvents, methanol extract had the greatest total phenolic concentration in Ficus microcarpa. Plant phenolic compounds play a significant role in scavenging because of their hydroxyl groups (Nunes et al., 2012). Research has shown that tannins have antibacterial, anticancer, and antiviral properties. Studies on flavonoidic derivatives have revealed numerous anti-inflammatory, antiviral, antibacterial, anti-allergic, and anti-cancer properties as reported by Montoro et al. (2005).

In our study, the highest amount of total proteins are present in the ethanolic extract of and in contrast the highest amount of total Carbohydrates observed in the aqueous extract of T. chebula fruit extracts. The total carbohydrate and protein contents has been apparently varied in the plants such as Zingiber officinale, Camellia sinensis and Annona muricata as reported by Serge Cyrille et al. (2021). In our study, the examination on the level of the different enzymatic antioxidant markers (SOD, catalase and Gpx) were found to be 0.46 µg, 97 µg and 127 µg respectively in the ethanolic fruit extract of T. chebula. Batinic-Haberle et al. (2015) reported that to counteract the harmful effects of ROS, the CAT and peroxidase must work in concert with SOD to remove O2 and H2O2. SOD usually comes into contact with singlet oxygen form ROS in its early phases, as well as free radicals that are successively eliminated with the aid of GPx and CAT. Also, the high level of presence of non-enzymatic antioxidant markers (Vitamin C and Vitamin E) in ethanolic fruit extract of T. chebula were proved in the current study. It was reported that a powerful chain-breaking antioxidant, vitamin E prevents the formation of reactive oxygen species molecules during the oxidation of fat and the spread of free radical reactions, an earlier study indicated that a 70 % ethanol extract of T. chebula fruits had good efficacy in terms of its capacity to scavenge free radicals (Hazra et al. 2010).

According to Sultana et al. (2007), ethanolic extract of T. arjuna has the greatest scavenging potential. In contrast, ethyl acetate, a solvent that is much less polar, has the lowest IC 50 value, according to Jegadeesware et al. (2014). So, in current study, the DPPH and Reducing power assay was done only for ehtanolic, aqueous and chloroform and petroleum ether extract was avoided as the solvent was less polar and low yield of phytochemicals. It was also found that, the ethanolic extracts of T. chebula fruits studied exhibited free radical scavenging properties in highest range of 96 % of inhibition in DPPH radical scavenging activity and reducing power assay. These findings agreed with those of Iloki-Assanga et al. (2015), who found that the order of acetone > methanol > aqueous > ethanol was found varied effectiveness at scavenging free radicals when comparing the extracts of Bucida buceras (Oak) and Phoradendron californicum (mesquite).

The ethanolic etxtract found rich in phytochemicals and recorded highest antioxidant activity were further analyzed using FTIR indicated the presence of following functional groups viz., alcohol, alkanes, Carboxylic acid, alkenes, Alkanes, Ethers and Halogen respectively. The functional groups of carboxylic acids and halogens in T. chebula has many therapeutic benefits. These are in line with Starlin et al. (2012), showed the ethanolic extracts of T. chebula indicated functional group components of organic hydrocarbons, halogens, and carboxylic acids through FTIR. The transition metal carbonyl compounds and aliphatic fluoro compounds were exclusively found ethanolic fruit extract of T. chebula (Parag and Pednekar, 2013).

Furthermore, the GCMS analysis of ethanolic fruit extract of T. chebula revealed the presence of 9 bioactive phytochemical compounds and it is identified that T. chebula contains Aldehydes, Phenols, Palmitic acid, Alcohols, Polyphenols, Gallic acid and alkanes. The furaldehyde and 2,5-furandicarboxaldehyde present in T. chebula has antimicrobial action, 2,4,di-t-butylphenyl are Antineoplastic and Dodecanoic acid, ethylester has antimalarial and antioxidant effect. Further, n-pentadecanol antioxidant, 1,2,3-Benzenetriol pyrogallol and 3,4,5 trihydroxy benzoic acid proved the antimicrobial, anticancer and antioxidant action. The compound Octadecanoicacid, ethyl ester has antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties and finally Hentriacontane has anticancer effect. Gallic acid (3, 4, 5-trihydroxybenzoic acid) has been reported to have antioxidant, antimutagenic, antitumor, anticancer, anti-inflammatory and apoptotic properties (Kahkeshani et al. 2019). When cells are signaling, the essential fatty acids linoleic and linolenic (9, 12 octadecanoic acid) play a critical role in the synthesis of lipid rafts.

5 Conclusion

The results of the current investigation showed that, among four solvent screened, the T. chebula fruits (ethanolic extract) showed variety of phytochemicals, including phenolic compounds, carotenes, alkaloids flavonoids, saponins, and amino acids etc. among others. Further, in vitro antioxidant activity of the ethanolic fruit extract of T. chebula was found to be higher and also proved highest level of radical scavenging activity. Accordingly, it can be inferred from the aforementioned study that this T. chebula fruits have not only medicinal properties and also be used as an antioxidant source. The study also suggests that T. chebula fruit may be a source of bioactive phytochemicals that may serve as an antibacterial, antifungal, anti-inflammatory, and anti-diabetic agent in addition to being a plant-based antioxidant. It is important to use this information to promote additional research so that it may be used in the pharmaceutical and food industries.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Mohamed Farouk Elsadek: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Khalid S. Al-Numair: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Data curation.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to extend their sincere appreciation for funding this work through the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSP2024R349), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Evaluation of phytochemical screening and analgesic activity of aqueous extract of the leaves of Microtrichia perotitii Dc (Asteraceae) in mice using hotplate method. Medicinal Plant Res.. 2013;3:37-43.

- [Google Scholar]

- Preliminary phytochemical screening and In vitro antioxidant activities of the aqueous extract of Helichrysum longifolium DC. BMC Complement. Altern. Med.. 2010;10:21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of antioxidant and antibacterial activities of Ficus microcarpa L. fill extract. Food Contrl.. 2008;19:940-948.

- [Google Scholar]

- The development of Terminalia chebula Retz. (Combretaceae) in clinical research. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed.. 2013;3(3):244-252.

- [Google Scholar]

- phenolic contents and antioxidant activity of some food and medicinal plants. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr.. 2005;56(4):287-291.

- [Google Scholar]

- Determination of serum tocopherol by colorimet-ric method. In: Varley’ s Practical Clinical Biochemistry (6th ed.). Portsmouth, NH, USA: Heinemann Professional Publishing; 1988. p. :902.

- [Google Scholar]

- Baker F. Determination of serum tocopherol by colorimet-ric method. Varley ’ s practical clinical biochemistry, 6th ed. Portsmouth, NH, USA: Heinemann Professional Publishing, 1988: 902.

- Phytochemical screening and antimalarial assessment of Abutilon mauritianum. Bacopa Monnifera and Datura Stramonium. Biokemistri. 2006;18:39-44.

- [Google Scholar]

- An educational overview of the chemistry, biochemistry and therapeutic aspects of Mn porphyrins – From superoxide dismutation to H2O2-driven pathways. Redox Biol.. 2015;5:43-65.

- [Google Scholar]

- A modified Specterophotometric assay of superoxide dismutase using nitrite formation by superoxide radicals. Ind. J. Biochem. Biophys.. 2000;37:201-204.

- [Google Scholar]

- Free-radical scavenging capacity and reducing power of wild edible mushrooms from northeast portugal: individual cap and stipe activity. Food Chem.. 2007;100:1511-1516.

- [Google Scholar]

- Stabilization of the Prussian blue color in the determination of polyphenols. J. Agric. Food Chem.. 1992;40(5):801-805.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of dietary selenium on erythrocyte and liver glutathione peroxidase in the rat. J Nutri. 1974;104:580-584.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparative study of the antioxidant and reactive oxygen species scavenging properties in the extracts of the fruits of Terminalia chebula, Terminalia belerica and Emblica officinalis. BMC Complement. Altern. Med.. 2010;10–20

- [Google Scholar]

- Solvent effects on phytochemical constituent profiles and antioxidant activities, using four different extraction formulations for analysis of Bucida buceras L. and Phoradendron californicum. BMC Res.. 2015;8:396.

- [Google Scholar]

- Quantification of total phenolics flavonoids and in vitro antioxidant activity of Aristolochia bracteata retz. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2014;6(1):747-752.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pharmacological effects of gallic acid in health and diseases: a mechanistic review. Iran. J. Basic Med. Sci.. 2019;22(3):225-237.

- [Google Scholar]

- Preliminary analysis of phytoconstituents and evaluation of anthelminthic property of Cayratia auriculata (In Vitro) Maedica (bucuR).. 2019;14(4):350-356.

- [Google Scholar]

- Protein measurement with the folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem.. 1951;193:265-275.

- [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of medicinal plants through proximate and micronutrients analysis. J. Plant Dev. Sci.. 2020;12(4):223-229.

- [Google Scholar]

- Indian medicinal plants: a potential source for Anticandidal drugs. Pharm. Biol.. 1999;37:237-242.

- [Google Scholar]

- Structure-antioxidant activity relationships of flavonoids isolated from different plant species. Food Chem.. 2005;92:349-355.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biological oxidations and antioxidant activity of natural products. In: In Book: Phytochemicals as Nutraceuticals - Global Approaches to Their Role in Nutrition and Health. 2012. p. :1-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- Selected methods for the determination of ascorbic acid in animal cells, tissues, and fluids. Methods Enzymol.. 1979;62:3-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Potential with FTIR analysis of Ampelocissus latifolia (roxb.) Planch. Leaves. Asian J. Pharma and Clinical Res.. 2013;6(1):67-73.

- [Google Scholar]

- Results of medically assisted procreation in France: are we so bad? Gynecology, Obstetrics & Fertility.. 2007;35:30-37.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antibacterial activity of antipsoriatic herbs: Cassia tora, Momordica charantia and Calendula officinalis. Int. J. Appl. Res. Natural Products.. 2008;1(3):20-28.

- [Google Scholar]

- Dillenia species: a review of the traditional uses, active constituents and pharmacological properties from pre-clinical studies. Pharm. Biol.. 2014;52:890-897.

- [Google Scholar]

- Inhibition of cancer cell growth by crude extract and the phenolics of Terminalia chebula retz. fruit. J. Ethnopharmacol.. 2002;81:327-336.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nutritional value, phytochemical content, and antioxidant activity of three phytobiotic plants from west Cameroon. J. Agric. Food ReS.. 2021;3:100105

- [Google Scholar]

- Antioxidative properties of xanthan on the autoxidation of soybean oil in cyclodextrin emulsion. J. Agric. Food Chem.. 1992;40:945-948.

- [Google Scholar]

- The antifungal activity of five Terminalia species checked by paper disk method. Int. J. Pharmaceutical Res. Develop.. 2011;3:36-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- Element and functional group analysis of Ichnocarpus frutescens R.Br. (Apocynaceae) Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci.. 2012;4(5):343-345.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antioxidant activity of phenolic components present in barks of Azadirachta indica, Terminalia arjuna, Acacia nilotica and Eugenia jambolana Lam. trees. Food Chem.. 2007;104:1106-1114.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytoprotective role of the aqueous extract of Terminalia chebula on renal epithelial cells. Int. Braz J Urol. 2012;38:204-213.

- [Google Scholar]

- Determination of extractable and bound condensed tannin concentrations in forage plants, protein concentrate meals and cereal grains. J. the Sci. Food and Agri.. 1992;58(3):321-329.

- [Google Scholar]

- Glycosides in medicine: the role of glycosidic residue in biological activity. Curr. Med. Chem.. 2001;8:1303-1328.

- [Google Scholar]

- The estimation of carbohydrates in plant extracts by anthrone. Biochem. J.. 1954;57(3):508-514.

- [Google Scholar]