Translate this page into:

Prevalence and antimicrobial mechanism of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae and its molecular properties

⁎Corresponding author at: Department of Medical Laboratory Sciences, College of Applied Medical Sciences, Majmaah University, Majmaah 11952, Saudi Arabia. m.palanisamy@mu.edu.sa (Palanisamy Manikandan)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background

The carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae poses a serious threat to public health because carbapenems are used as a final resort to treat K. pneumoniae-mediated infections in humans.

Methods

Samples were collected from various clinical specimens including skin swabs, anal swabs, wound swabs, oral swabs, and sputum by the standard method and K. pneumoniae strains were isolated. Biofilm-forming characters were determined. The antibiotic resistance pattern was analyzed by the Kirby–Bauer disk diffusion method. Carbapenem resistance properties were tested using the imipenem and meropenem antibiotics. The carbapenemase genes (blaKPC and blaNDM) were determined.

Results

A total of 11 cephalosporin-resistant K. pneumoniae (CRKP) strains were isolated from the samples. The screened CRKP strains exhibited multi-drug resistance and non-susceptible to imipenem, ceftazidime, piperacillin, ceftriaxone, cefazolin, ampicillin, aztreonam, and cefotetan antibiotics. A total of 79.4 % K. pneumoniae isolates showed positive results on String-forming test. About 82.1 % of isolates showed mucoid colonies and 59 % of K. pneumoniae strains formed biofilm (p < 0.01). Out of 11 isolates, four strains exhibited Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase type, three strains produced metallo-β-lactamases (MBL), and four strains exhibited as carbapenemase types. A total of 63.5 % Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing strains showed very low MIC value (<0.05 mg/L).

Conclusions

Drug-resistance K. pneumoniae was isolated from clinical specimens that were screened. The continuous monitoring of drug-resistance genes are required to make policy decisions.

Keywords

Klebsiella pneumoniae

Carbapenem-resistant

BlaKPC

BlaNDM

1 Introduction

Antibiotic resistance is one of the major healthcare issues worldwide. The increasing interest towards multidrug resistance, and exploring molecular mechanisms and analyzing resistance genes were increased rapidly (Rodriguez-Mozaz et al., 2015). The unrestricted application of commercial antibiotics is a major factor and associated with the increase in antimicrobial resistant microorganisms (Gottlieb and Nimmo, 2011). For the past few decades, antibiotics are not only applied in the healthcare sector but also in agriculture and veterinary. The increased amount of drug-resistant bacteria as well as antibiotic-resistance genes was prevalent in animal and human feces. Microbiota from human beings can be enriched and altered with antibiotic resistance bacteria, hence, humans can be considered as a reservoir of antibiotic resistance genes and bacteria (Rodriguez-Mozaz et al., 2015). Humans acquired antibiotic resistance through two different pathways: Community and Hospital-acquired. Moreover, antibiotic resistance bacteria are highly common in hospital and healthcare settings (Hocquet et al., 2016). Nosocomial bacteria termed “ESKAPE’’ include both Gram-negative and Gram-positive characterized by various drug resistance patterns and are involved in life-threatening infections in humans (Santajit and Indrawattana, 2016). Antibiotic resistance is a major burden and resistant to final-line resort antimicrobials, such as glycopeptides, fluoroquinolones, and carbapenems, and cephalosporins (third-generation antimicrobials) posing the serious threat to humans (Mckenna, 2013). Antibiotic resistance against these types of drugs was determined in the hospital environment and is being identified in community-acquired infections. These include vancomycin-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae, multidrug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii and Escherichia coli (Cassini et al., 2019). Moreover, carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii and third-generation cephalosporin-resistant and carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae are considered critical-priority bacteria, whereas vancomycin resistant enterobaceriaceae, together with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, has high priority based on WHO list of antibacterial resistant bacteria. The prevalence of K. pneumoniae, especially carbapenems-resistant strains is a global healthcare concern of various countries, including Africa, Asia and Europe. The beta-lactamases producing K. pneumoniae among Enterobacteriaceae have been already reported and the subtype of beta-lactamases was metallo-β-lactamases and class D β-lactamases (Findlay et al., 2017). The main aim of the present study was to analyze the prevalence of drug resistant carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae in the specimens using biochemical and molecular methods.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Samples

The test strains were collected at a microbiology lab where they were isolated from a variety of clinical specimens, such as sputum, skin, anal, and wound swabs, as well as swabs from patients who had been admitted to the hospitals between March 2021 and February 2022.

2.2 Growth characteristics of K. pneumoniae, mucinous phenotype and biofilm formation

The mucinous phenotype of K. pneumoniae was evaluated as described previously (Yang et al., 2019). Briefly, the isolated K. pneumoniae strains were spread on Columbia blood agar plates and incubated for 24 h at 37°C. The colony was dipped in the inoculum ring and left the inoculum ring for 24 h. The development of colonies on the adhesive wire was analyzed and the adhesive formed >0.5 cm was considered as positive. The bacterial strains were cultured on MacConkey agar medium and incubated for 24 h at 37°C. After 24 h, the development of mucoid colonies was observed. The biofilm-forming potential was analyzed by evaluating the adhesion to the microtiter plate method. Briefly, the isolated bacterial strains (18 h) were inoculated into the 96-well plate containing nutrient broth medium. The microtiter plates were incubated for 48 h at 37°C and the well was washed with phosphate-buffered saline (three times) and dried at 50°C. The wells were stained with 100 μL of 1 % crystal violet for 10 min and washed the well to remove the excess stain. It was air-dried and the wells were flooded with 350 μL of 95 % ethanol and agitated for 10 min. The absorbance was read at 570 nm against the reagent blank. The colour intensity was measured and was classified as weak biofilm producers, moderate biofilm producers and very strong biofilm producers.

2.3 Antibiotic susceptibility analysis

The antibiotic resistance pattern was analyzed by the Kirby–Bauer disk diffusion method using Mueller–Hinton agar plates (Zhang et al., 2020). Carbapenem resistance properties of K. pneumoniae were evaluated using the imipenem and meropenem antibiotic disks. The antibiotics used were: amikacin, imipenem, ceftazidime, piperacillin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, ceftriaxone, ampicillin, levofloxacin, cefazolin, cefotetan. gentamicin, aztreonam and sulbactam. Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ATCC 27853) and Escherichia coli (ATCC 25922) were used as the standard stains.

2.4 Detection of carbapenemases from drug resistant Klebsiella isolates

Meropenem and Imipenem resistant Klebsiella strains were used for carbapenemases screening using the modified Hodge test (MHT method), and the meropenem combined disk test (CDT method) as described previously. Briefly, the bacterial strains were cultured in MHB medium and it was diluted appropriately (1:10 dilution of 0.5 McFarland) E. coli suspension (ATCC 25922) was placed on MHA plates and meropenem was loaded at the centre of the plate. The selected Klebsiella strains were inoculated in a straight line (edge of the plate to the edge of the meropenem disk). A positive control (K. pneumoniae ATCC BAA-1705) was used to validate the results. The culture plates were incubated at 32°C for 24 h and the results were observed. CDT method was used for the determination of carbapenemase-producing enterobacteria as described earlier by Pournaras et al. (2013). The drug-resistant strains were inoculated on MHA plates. Then antibiotic discs meropenem with phenylboronic acid, and meropenem, meropenem with PBA, and meropenem with EDTA were placed onto the MHA plates. The plates were incubated for 24 h at 32°C and the result was compared with the control (Tsakris et al., 2010).

2.5 Extraction of DNA and analysis of carbapenemase genes (blaKPC and blaNDM)

K. pneumoniae DNA was extracted using a DNA purification kit (Qiagen, Germany) as described earlier (El-Badawy et al., 2017). Briefly, the bacterial colonies were mixed in 200 μL of Millipore double distilled water in a 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube. The culture was vortexed for a few seconds and kept in a boiling water bath at 94 °C for 8 min to lyse the selected culture. It was further centrifuged for 10 min at 10,000 rpm. The total genomic DNA was retained from the supernatant and was measured using a Nanodrop Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, USA). Polymerase chain reaction was carried out to detect blaKPC and blaNDM carbapenemase genes by forward and reverse primers. The amplified PCR products were analyzed by 1.5 % agarose gel electrophoresis. The amplified gene product was further visualized under a UV trans-illuminator.

2.6 Antimicrobial activity of antibiotics against carbapenemase type bacterial strains

A microbroth dilution method was used for the determination of antimicrobial susceptibility. Briefly, the culture medium was sterilized and loaded into a microtiter plate and antimicrobial agents were added at various concentrations and combinations and incubated for 24 h at 28 ± 1 °C. After 24 h, the optical density was measured using a spectrophotometer (Wu et al., 2020). A total of fifteen antimicrobial agents (ampicillin–sulbactam, ampicillin, piperacillin–tazobactam, ceftazidime, cefepime, cefoperazone–sulbactam, amikacin, Gentamicin, Levofloxacin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazol, Ceftazidime–avibactam, Meropenem–Vaborbaktam and Imipenem/cilastatin/relebactam) were used. To prevent the control of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase microbes, cephalosporin was selected at two different combinations (ceftazidime-clavulanate and cefotaxime-clavulanate). The MIC value was determined as described previously (Malar et al., 2020).

3 Results

3.1 Distribution of carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae

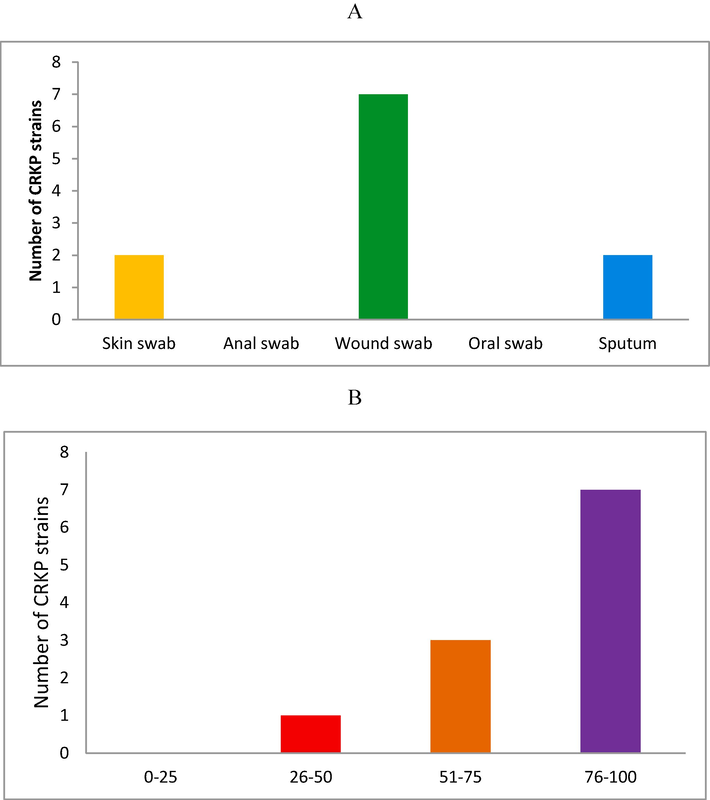

A total of 108 patients were subjected to the determination of carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae. In 108 patients, carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae (CRKP) strains were isolated and a total of 11 CRKP strains were obtained in this study. Two CRKP isolates were isolated from the skin, whereas seven were isolated from the wound and the remaining two were obtained from the sputum collections (p < 0.01). A significant CRKP population was detected in the wound sample and no CRKP positive strains were detected in the anal and oral swabs (Fig. 1A). The analyzed age of CRKP-positive patients varied from 9 to 78 years. The old age group (76–100) represented 63.3 % of CRKP isolates cases and this proportion was significantly less (36.6 %) for the 26–75 age groups (p < 0.01) (Fig. 1B).

Distribution of carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae from the patients admitted to the hospitals (A). Frequency of CRKP bacteria among different age groups (B).

3.2 Antibiotic susceptibility testing

The drug resistance patterns of CRKP strains were illustrated in (Table 1). The isolated CRKP bacteria exhibited non-susceptible to imipenem, ceftazidime, piperacillin, ceftriaxone, cefazolin, ampicillin, aztreonam, and cefotetan. The CRKP strains exhibited intermediate or sensitivity to amikacin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, levofloxacin, gentamicin, and sulbactam. In our study, 68.3 % of the isolated strains exhibited multidrug resistance. The MIC values were determined against CRKP strains and the susceptibility patterns of isolates are presented in Table 1. S – sensitive, I – intermediate, R – resistant.

Antibiotics

Antibiotic susceptibility (%)

MIC (µg/mL)

S

I

R

S

I

R

Imipenem

0

0

100

1

3

≥5

Ceftazidime

0

0

100

5

10

≥20

trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole

56.5

0

43.5

4

8

≥25

Ampicillin

0

0

100

4

8

≥16

Piperacillin/tazobactam

0

0

100

25

75

≥125

Ceftriaxone

0

0

100

1

4

≥10

Amikacin

50

10

40

8

16

≥32

Cefazolin

0

0

100

8

16

≥32

Gentamicin

42

18

40

2

4

≥8

Ampicillin/Sulbactam

0

0

100

8

16

≥32

Aztreonam

0

0

100

2

4

≥8

Cefotetan

0

0

100

32

64

≥128

Levofloxacin

54.5

2.9

42.6

4

8

≥16

Meropenem

0

0

100

5

10

≥125

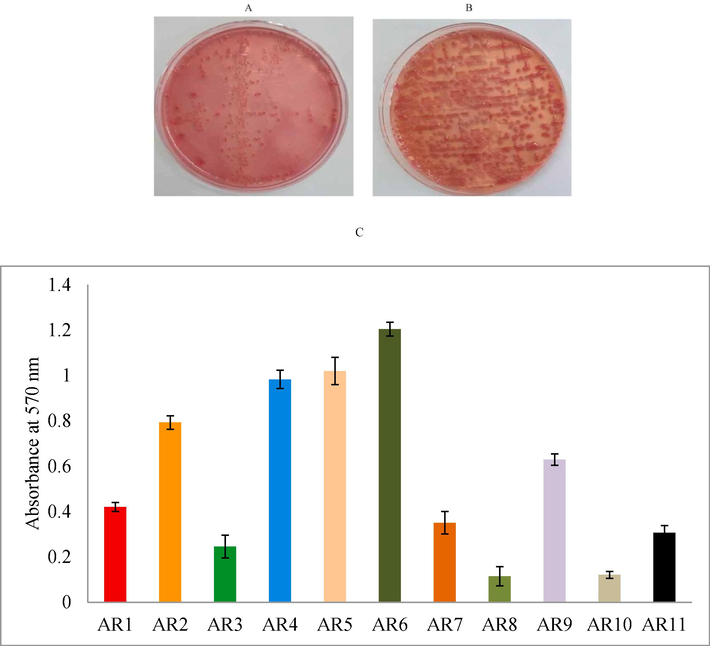

3.3 Mucinous screening, mucoid colonies development and biofilm-forming characteristics of K. pneumoniae

A total of 79.4 % K. pneumoniae isolates showed positive results on the string-forming test. Most of the string-formed K. pneumoniae isolates exhibited multidrug resistance. In the present study, mucoid and pink colour colonies were observed on MacConkey agar plates. The non-mucoid colonies were also observed. About 82.1 % of isolates showed mucoid colonies and the remaining 17.9 % exhibited non-mucoid properties (Fig. 2A and B). A total of 11 K. pneumoniae isolates were tested for the analysis of biofilm production and these isolates were CRKP types. Among multi-drug resistant bacterial strains, 59 % of K. pneumoniae strains presented biofilm-formation and the remaining isolates were non-multidrug resistant strains. The strains AR4, AR5, and AR6 exhibited maximum biofilm-production and the absorbance values were 0.983 ± 0.04, 1.02 ± 0.06, and 1.205 ± 0.03, respectively (Fig. 2C).

Development of non-mucoid (A) and mucoid (A) K. pneumoniae colonies on MacConkey agar plates. The isolates were placed on MacConkey agar medium and incubated for 24 h. (C) The biofilm-producing potential of K. pneumoniae isolated from the clinical specimens.

3.4 Carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae

Carbapenemase-producing bacterial strains were determined using Modified Hodge Test (MHT) and Combined disk test (CDT). MHT analysis revealed the presence of 9 carbapenemases-producing strains (63.6 %) and a combined disk test detected carbapenemases-producing strains. Out of 11 isolates, four strains exhibited KPC type, three strains produced MBL, and four strains showed KPC/MBL types. The variation in the result revealed sensitivity between the selected methods (Table 2). +: positive; −: negative; KPC − K. pneumoniae carbapenemases; MBL – metallo-β-lactamases.

K. pneumoniaestrains

Modified Hodge Test

Combined disk test

AR1

+

KPC

AR2

−

KPC/MBL

AR3

+

MBL

AR4

+

KPC

AR5

+

KPC/MPL

AR6

+

KPC/MBL

AR7

−

MBL

AR8

+

KPC

AR9

+

MBL

AR10

+

KPC/MBL

AR11

+

KPC

3.5 Detection of carbapenemase-producing genes (blaNDM and blaKPC genes) from K. pneumonia strains

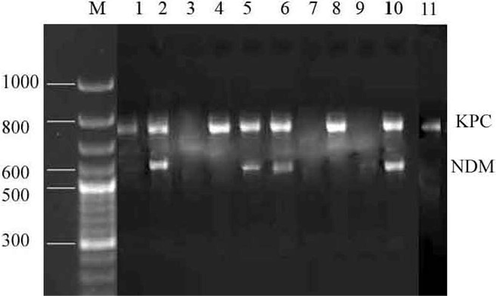

The isolated 11 carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae strains were subjected to the determination of blaNDM and blaKPC genes. The blaNDM was detected in four K. pneumoniaestrains while blaKPC gene was detected in 8 bacterial strains. Fig. 3 presented the amplified blaNDM and blaKPC genes on agarose gel electrophoresis. Of the 11 drug-resistant isolates, four bacteria exhibited both blaNDM and blaKPC genes. Statistical analysis revealed that there is a significant variation in the presence of drug resistance genes (blaNDM and blaKPC) among the K. pneumoniae strains (p < 0.01).

Detection of the carbapenemase genes (KPC and NDM) in carbapenemase-synthesizing K. pneumoniae isolates 1 to 11. Lane M –: DNA ladder, Lane 1–11: bla KPC and bla NDM genes of K. pneumoniae.

3.6 In vitro antibiotic activity against carbapenemase-producing carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae

In vitro antibiotic activity was tested against carbapenemase-producing carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae. Ceftazidime (non-β-lactam β-lactamase inhibitor) in combination with avibactam (non-β-lactam β-lactamase inhibitor) was tested against KPC-producing K. pneumoniae and all strains showed sensitivity. KPC-producing strain presented MIC ranged between 0.025 and 1 mg/L. The combination of Meropenem–Vaborbaktam was more effective than Ceftazidime-Vaborbaktam. K. pneumoniae was evaluated to test the susceptibility against cefiderocol (beta-lactamase inhibitor). The MIC value of cefiderocol was tested on K. pneumoniae, and KPC-producing strains showed lower MIC values than other tested antibiotics (see Table 3).

Ceftazidime–

KPC (n)

Meropenem–

KPC (n)

Cefiderocol

KPC (n)

avibactam MIC

Vaborbaktam MIC

MIC (mg/L)

(mg/L)

(mg/L)

0.025

1

0.025

1

0.0125

7

0.075

1

0.05

4

0.025

2

0.125

5

0.075

2

0.05

2

0.525

1

0.125

1

0.075

0

0.825

2

0.15

0

0.1

0

1

1

0.25

3

0.125

0

4 Discussion

K. pneumoniae is one of the opportunistic pathogenic bacteria that cause nonhospital infections and severe nosocomial infections. This pathogenic strain produces carbapenemases that have the potential to degrade β-lactam antibiotics, including various synthetic carbapenem antibiotics. The increasing emergence of β-lactam antibiotics cause increased mortality among hospitalized cases and carbapenems are considered as the antibiotics of final resort to treat bacterial infections from Gram-negative type (Politi et al., 2019). World Health Organization listed K. pneumoniae as a virulent organism (Aires-de-Sousa et al., 2019). These pathogenic strains were isolated from the skin, sputum, and wound samples. This organism was characterized with asymptomatic colonization on health care workers, patients, and it survives on various non-sterile medical equipment and apparatus (Moradigaravand et al., 2017). This facilitates for the simple transmission of carbapenem-hydrolyzing enzymes-coded genes from one plasmid to another. Moreover, several drug resistance mechanisms can be available on the same plasmid, which makes to the development of multidrug-resistant K. pneumoniae species. Aires-de-Sousa et al. (2019) isolated drug-resistant K. pneumoniae from the rectum of the patients and urine contributed 43.5 %, and 32.6 %% respectively. The present study revealed that the maximum number of K. pneumonias strains in a wound sample (n = 7) than other sources. The prevalence of K. pneumoniae varied based on the degree of infection and only 8.7 % of isolates were identified in the blood sample previously (Aires-de-Sousa et al., 2019). It has been previously reported that the carbapenemase-enzyme-producing K. pneumoniae strains exhibited antibiotic resistance against various drugs, including penicillins and cephalosporins (Gao et al., 2020). Durdu et al. (2019) reported that the isolated K. pneumoniae strains presented 91.3 % resistance to cefepime and 72.6 % resistance to ciprofloxacin. Moreover, the research work performed by Singh et al. (2017) reported 100 % resistant strain to cefepime and exhibited 70 % resistance to cefotaxime and 65 % resistance to ciprofloxacin. In our study, the selected K. pneumoniae showed 100 % resistance to imipenem, ceftazidime, piperacillin, ceftriaxone, cefazolin, ampicillin, aztreonam, and cefotetan. Apondi et al. (2016) reported that the isolated K. pneumoniae strains exhibited 82.8 % resistance to gentamicin and 21 % of bacteria showed resistance to amikacin. In the present study, 40 % of the isolated strains exhibited resistance against gentamicin and amikacin and the drug-resistant patterns are diverse among the type strains. The increased resistant K. pneumoniae strains were reported previously. A total of 99 % of strains exhibited resistance to meropenem and all the strains showed resistance to imipenem these findings revealed increased carbapenem resistance among bacterial strains (Zheng et al., 2017). The percentage of isolates resistant to meropenem and imipenem was 100 %. K. pneumoniae is one of the carbapenemases secreting bacteria and is classified as MBL (NDM), KPC and OXA-48 families (Yonekawa et al., 2020). It has been reported previously by WHO stated the prevalence of K. pneumoniae strains was more than 50 %. Recent epidemiological studies revealed that specific carbapenemases were predominant in various parts of the world. In Pakistan, India, and Sri Lanka and other Asian countries, NDM-producing K. pneumoniae were predominant. In the United States, Australia, China, Greece, South America, and Italy, NDM type carbapenemase type. Moreover, OXA-48 type carbapenemase-producing strains are endemic in North Africa, and the Middle East (Suay-García and Pérez-Gracia, 2021). In this study, the blaNDM was detected in four K. pneumoniae strains while blaKPC gene was detected in 8 bacterial strains. Of the 11 drug-resistant isolates, four bacteria exhibited both blaNDM and blaKPC genes. In China, KPC-producing strains contributed to >50 % K. pneumoniae population and NDM-type carbapenemases producing strains contributed to 11 % population and 37 % of strains were OXA-48 type carbapenemases (Han et al., 2020).

5 Conclusions

The present finding revealed the emergence of multidrug-resistant carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae in hospitalized patients. The tested bacterial strains exhibited resistance to multiple key antibiotics such as imipenem, ceftazidime, piperacillin, ceftriaxone, cefazolin, ampicillin, aztreonam, and cefotetan, which are regarded as serious threat to public health. The most common gene identified was blaKPC, while the blaNDM gene was less frequent.

Funding

The authors extend their appreciation to the deputyship for Research & Innovation, Ministry of Education in Saudi Arabia for funding this research work through the project number (IFP-2022-09).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Palanisamy Manikandan: Methodology, Investigation, Validation. Saleh Aloyuni: Conceptualization; Resources. Ayoub Al Othaim: Investigation, Funding acquisition, Validation, Writing – original draft. Ahmed Ismail: Conceptualization. Alaguraj Veluchamy: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Bader Alshehri: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Ahmed Abdelhadi: Validation, Methodology, Funding acquisition. Rajendran Vijayakumar: Methodology, Investigation, Writing – original draft.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to the deputyship for Research & Innovation, Ministry of education in Saudi Arabia for funding this research work through the project number (IFP-2022-09).

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Epidemiology of carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in a hospital, Portugal. Emerg. Infect. Dis.. 2019;25(9):1632

- [Google Scholar]

- High prevalence of multi-drug resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in a tertiary teaching hospital in Western Kenya. Afr. J. Infect. Dis.. 2016;10(2):89-95.

- [Google Scholar]

- Attributable deaths and disability-adjusted life-years caused by infections with antibiotic-resistant bacteria in the EU and the European Economic Area in 2015: a population-level modelling analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis.. 2019;19(1):56-66.

- [Google Scholar]

- Risk factors affecting patterns of antibiotic resistance and treatment efficacy in extreme drug resistance in intensive care unit-acquired Klebsiella pneumoniae infections: a 5-year analysis. Med. Sci. Monit... 2019;25:174

- [Google Scholar]

- Molecular identification of aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes and plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance genes among Klebsiella pneumoniae clinical isolates recovered from Egyptian patients. Int. J. Microbiol.. 2017;2017

- [Google Scholar]

- Characterization of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in the West Midlands region of England: 2007–14. J. Antimicrob. Chemother.. 2017;72(4):1054-1062.

- [Google Scholar]

- The transferability and evolution of NDM-1 and KPC-2 co-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae from clinical settings. EBioMedicine. 2020;51:102599

- [Google Scholar]

- Antibiotic resistance is an emerging threat to public health: an urgent call to action at the Antimicrobial Resistance Summit 2011. Med. J. Aust.. 2011;194(6):281-283.

- [Google Scholar]

- Dissemination of carbapenemases (KPC, NDM, OXA-48, IMP, and VIM) among carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae isolated from adult and children patients in China. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol.. 2020;10:314

- [Google Scholar]

- What happens in hospitals does not stay in hospitals: antibiotic-resistant bacteria in hospital wastewater systems. J. Hosp. Infect.. 2016;93(4):395-402.

- [Google Scholar]

- In-vitro phytochemical and pharmacological bio-efficacy studies on Azadirachta indica A. Juss and Melia azedarach Linn for anticancer activity. Saud. J. Biol. Sci.. 2020;27(2):682-688.

- [Google Scholar]

- The last resort: health officials are watching in horror as bacteria become resistant to powerful carbapenem antibiotics–one of the last drugs on the shelf. Nature. 2013;499(7459):394-397.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evolution and epidemiology of multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in the United Kingdom and Ireland. MBio. 2017;8(1):1110-1128.

- [Google Scholar]

- Emergence of NDM-1-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in Greece: evidence of a widespread clonal outbreak. J. Antimicrob. Chemother.. 2019;74(8):2197-2202.

- [Google Scholar]

- A combined disk test for direct differentiation of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in surveillance rectal swabs. J. Clin. Microbiol.. 2013;51(9):2986-2990.

- [Google Scholar]

- Occurrence of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes in hospital and urban wastewaters and their impact on the receiving river. Water Res.. 2015;69:234-242.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance in ESKAPE pathogens. BioMed Res. Int.. 2016;2016

- [Google Scholar]

- Antibiotic resistance determinants and clonal relationships among multidrug-resistant isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Microb. Pathog.. 2017;110:31-36.

- [Google Scholar]

- Present and future of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae infections. Adv. Clin. Immun. Med. Microbiol. 2021:435-456.

- [Google Scholar]

- A simple phenotypic method for the differentiation of metallo-β-lactamases and class A KPC carbapenemases in Enterobacteriaceae clinical isolates. J. Antimicrob. Chemother.. 2010;65(8):1664-1671.

- [Google Scholar]

- Characterization of biofilm formed by multidrug resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa DC-17 isolated from dental caries. Saud. J. Biol. Sci.. 2020;27(11):2955-2960.

- [Google Scholar]

- High rate of multiresistant Klebsiella pneumoniae from human and animal origin. Infect Drug Resist. 2019:2729-2737.

- [Google Scholar]

- Molecular and epidemiological characteristics of carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae clinical isolates in Japan. mSphere. 2020;5(5):10-1128.

- [Google Scholar]

- Probiotic characteristics of Lactobacillus strains isolated from cheese and their antibacterial properties against gastrointestinal tract pathogens. Saud. J. Biol. Sci.. 2020;27(12):3505-3513.

- [Google Scholar]

- Molecular epidemiology and risk factors of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae infections in Eastern China. Front. Microbiol.. 2017;8:241079

- [Google Scholar]