Translate this page into:

Phytonutrient and antinutrient components profiling of Berberis baluchistanica Ahrendt bark and leaves

⁎Corresponding author. aliakbar.uob@gmail.com (Ali Akbar)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Objectives

Plants are the most prevalent primary natural source of active medications. Berberis baluchistanica Ahrendt is known for the treatment of various ailments. Bioactive components, nutritional and antioxidant capacity of Berberis baluchistanica bark and leaves ethanolic extracts were evaluated in this study.

Methods

Total phenolics, flavonoids, antioxidant, nutritional and anti-nutritional contents were analyzed. Analysis of bioactive components identified the presence of tannins, cardiac glycosides, flavonoids, coumarin, alkaloids, phenolics, saponins, steroids, anthraquinones and terpenoids. The capability of donating hydrogen was analyzed by their 50% inhibition concentration (IC50).

Results

The bark possessed lower IC50 = 0.678 mg/mL and higher inhibition percentage of DPPH radical, compared to leaves IC50 = 0.785 mg/mL. The Ferric reducing antioxidant power of bark was relatively higher IC50 = 0.871 mg/mL than leaves IC50 = 0.996 mg/mL. The phenolic content of bark was 37.52 ± 1.56 mg GAE/g and that of leaves 28.32 ± 0.66 mg GAE/g, the total flavonoid contents in bark and leaves were 8.68 ± 0.93 and 11.81 ± 1.49 mg QE/g. Total proteins of the bark and leaves were 7.69 ± 0.65 mg BSAE/g and 3.63 ± 0.54 mg BSAE/g and carbohydrate contents of the bark and leaves were 4.46 ± 0.55 mg GE/g and 8.38 ± 0.71 mg GE/g respectively. The oxalate contents of bark were 0.12 ± 0.02 mg/g and leaves were 0.14 ± 0.19 mg/g and the phytate % composition of bark was 0.17 ± 0.24 % and leaves were 0.25 ± 0.08 % respectively.

Conclusions

The determination of these compounds attaining a range of medicinal properties helps in maintaining the traditional use of bark and leaves extracts of Berberis baluchistanica in various biomedical fields.

Keywords

Bioactive components

DPPH

Antioxidant activity

Total phenolic

Nutrients

1 Introduction

Plants have always great significance in health maintenance and promote the eminence of human life. The majority of people rely on local medicines for their basic health needs (Abdullah et al., 2021). Medicinal plants are traditionally used to treat diverse diseases like fever, cough, internal injury, wound healing, removal of kidney stones, rheumatism and other infections (Gul et al., 2022a, 2022b). Herbal medicines commonly prepared from crude plant extract comprising a variety of numerous bioactive components like polyphenols, terpenoids alkaloids and minerals possessing major antioxidant, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, cytotoxic and chemo preventive effects that provide protection against a number of infections. The herbal remedies containing these bioactive components (also known as plant secondary metabolites) are used as an alternative to laboratory made pharmaceuticals that are harmful to both humans and the environment (Javed et al., 2012). According to (Fahad et al., 2021) the bioactive components present in medicinal plants comprising strong antioxidant potential that have the power to reduce free radical, their production rate and also decrease lipids peroxidation that cause a variety of human diseases. These bioactive components and natural antioxidants discovered have increased their extensive nutritional and therapeutic value.

Berberis is a known genus belongs to family Berberidaceae, with 650 species and 15 genera (Behrad et al., 2022). It is one of the oldest species of angiosperm and has significant economic and therapeutic value because it contains the important phytochemical berberine (Nazir et al., 2021). Diverse Bioactive components found in Berberis include oleanolic acid, palmatine, steroids, saponins, alkaloids, flavonoids, terpenoids and tannins (Jahan et al., 2022). The antioxidant, anti-diabetic and anti-inflammatory properties of Berberine have also been recently published (Xu et al., 2021).

Berberis baluchistanica is a well-known therapeutic plant recognized as Zralag in Pashto, Korae in Balochi and Archin in Brahvi language. The plant is found in Balochistan, is a member of the Berberidaceae family. It is a 3 m tall evergreen shrub with crimson, brown to red stems. The leaves are thick and rigid and the flowers are 7–10 mm long and yellow. Its flowering period is March-May, found in Ziarat, Harboi, Kalat and Zarghun areas (Muddassir et al., 2022). The plant is considered as nontoxic and consumed as a powder or decoction. Due to its berberine content, the plant is used to treat a number of disorders (Sarangzai et al., 2013; Pervez et al., 2019). Bioactive components profile analysis of roots extracts of Berberis baluchistanica was accomplished by (BATOOL et al., 2019). Previously (Kakar et al., 2012) reported that the roots extract have high antibacterial activity against a broad collection of harmful microorganisms. The plant is medicinally beneficial as it contains bioactive substances with antioxidant and antibacterial effects. Though the plant is widely utilized in traditional medicines, fewer studies have been carried out on its bioactive components. There has been a lot of interest in evaluating the bioactive component of therapeutic plants, their antioxidant and antimicrobial potential and more research should be done to discover the curative potential for treating various health issues. For that reason, current research was aimed to carry out the comparative assessment of the total phenolics, flavonoid content, antioxidant potential, nutritional and anti-nutritional contents of Berberis baluchistanica bark and leaves extracts.

2 Material and method

2.1 Plant collection

Berberis baluchistanica was collected from district Ziarat of Balochistan and the study area is geographically extended between latitude 67°42′87″ East longitudes and 30°48′64″ North latitudes. The identification was done by taxonomists Dr. Shazia Saeed Assistant Professor Department of Botany, University of Balochistan. The plant was deposited when the voucher specimens were prepared.

2.2 Sample preparation

The bark and leaves were removed, washed and dried in the shade for 2–3 weeks at room temperature with controlled humidity. For further analysis, the dried parts were each finely ground with an electrical grinder and kept in desiccators (Uddin et al., 2022).

2.3 Maceration extraction

For bioactive compounds extraction, 100 g of fine ground powder was applied in 1 L ethanol with 1:10 ratio using standard reported protocols of (Gul et al., 2022a, 2022b). To avoid light exposure, the procedure was carried out in a dark room. The flasks were shaken at predetermined intervals. With Whatman filter No. 1, the ethanolic mixture was filtered. The extracts were dried, and dried samples were then analyzed further.

2.4 Bioactive components analysis

The bioactive components analysis of ethanolic extracts of bark and leaves was carried out to identify and detect the presence of Alkaloids, Anthraquinones, Tannins, Saponins, Flavonoids, Quinones, Steroids, Terpenoids, Coumarin, Glycosides, and Phlobatannins in samples (Akbar et al., 2019).

2.5 Total phenolic content analysis

For total phenolic contents of extracts, the Folin-Ciocalteu reagent procedure from (Akbar et al., 2019) was attempted with slight modification. Briefly (1 mg/mL) of stock solutions were diluted with de ionized water to prepare various dilutions up to 0.0625 mg/mL. The extracts (0.5 mL) were properly mixed with Folin-Ciocalteu reagent (2 mL) and incubated for 5 min at room temperature before being neutralized with 2 mL of 10 % (Na2CO3) and incubated for 30 min. Ethanol (95 %) was used as blank. The calibration curve was generated using various proportions of Gallic acid and absorbance was checked at 750 nm. The outcomes were mentioned in mg of Gallic acid equivalent (GAE) per g of dried sample weight.

2.6 Total flavonoid content analysis

Using the Aluminum chloride colorimetric method, the total flavonoid content was verified, as detailed by (Tareen et al., 2021). Simply, 95 % ethanol (1.5 mL) was put into 0.5 mL (1 mg/mL) of each extract and 0.5 mL of 5 % NaNO2 solution. After 5 min AlCl3·6H2O (0.1 mL, 10 %), 1 M NaOH (0.5 mL) and 2 mL of deionized water was added and incubated at 25 °C for 40 min. Absorbance was checked at 415 nm using a (T60 UV VIS Spectrophotometer). The findings were presented in milligram of Quercetin equivalents per g of sample (mg QE/g sample). Each experiment was repeated three times.

3 Antioxidant activity

3.1 DPPH free radicals scavenging activity

In the presence of DPPH stable radical, the hydrogen donating efficiency of extracts was measured. From the stock solution, several concentrations of each extract were prepared. Further 50 µL of each extract was treated with 0.1 mM DPPH (0.5 mL) solution, agitated and allowed to react at normal temperature in a dark for 30 min. Ascorbic acid was applied as a control. The decline in absorbance at 516 nm was used to detect DPPH decolorization. The ethanol served as a blank, while the DPPH solution a control (Sadiq et al., 2015). The preceding equation was employed to calculate the percentage inhibition:

Where, AS is the absorbance of each extract and AC is the Absorbance of Control.

The IC50 values characterize the antioxidant potential of the extract by describing the concentration of sample extract necessary to scavenge 50 % of the DPPH free radical. The scavenging activities were plotted against varied concentrations of each extract and represented in mg/mL to create the relationship curve.

3.2 Ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) activity

The FRAP test conformed to the instructions from (Benzie and Strain, 1996) with slight modifications. In brief, 300 mM Acetate buffer, 10 mM TPTZ solution formulated in 40 mM HCL and 20 mM ferric chloride hexahydrate solution comprised the stock solution. Then 0.5 mL of each extract (1 mg/mL) was placed in separate test tubes, followed by 2 mL distilled water and 4 mL of FRAP solution. For 30 min, the extracts were left to react with FRAP in the dark. The product's absorbance was read at 593 nm by putting FeSO4 as standard. The assay was performed in triplicate and the percentage reduction was calculated using the equation:

3.3 Protein evaluation by Lowry’s method

Lowry's method was employed to calculate the protein content (Lowry et al., 1951). To 0.5 mL of each extract, 4 mL of reagent 1 (46 mL of 2 % of sodium carbonate made in 0.1 N sodium hydroxide + 1 % of sodium potassium tartrate 2 mL + 0.5 % copper sulphate pentahydrate 2 mL) was added and incubated for 15 min. Following that, 0.5 mL of reagent 2 (1 mL Folin-Ciocalteau reagent, 2 mL distilled water in a 1:2 ratio) was immediately added and kept for 25 min. The standard was Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA), and the blank was de ionized water. The absorbance was checked at 650 nm. The protein concentration was evaluated and represented as mg BSAE/g of sample (Fahad et al., 2021).

3.4 DuBois carbohydrate method

Carbohydrates were calculated using the Phenol Sulphuric reagent procedure. Simply add 0.05 mL of phenol (80 %) to 2 mL of extract and 6 mL of concentrated sulfuric acid. After allowing the sample to stand for 10 min, the mixture was placed at 30° C for 20 min. The color variation was noticed before reading was taken. The absorbance was checked at 510 nm. The blank was de ionized water, and the standard was glucose. The steps were all completed in triplicate, and the outcomes were presented as mg GE/g.

4 Antinutrients analysis

4.1 Determination of oxalate

Powdered sample of bark and leaves (3 g) was added in distilled water (190 mL) and boiled for 1 h. Before digestion at 100 °C, 10 mL of 6 M HCl was appended, was cooled and filled up to 240 mL.

4.2 Oxalate precipitation and titration

Half of the filtered mixture (125 mL) was placed in two beakers, followed by the drop wise adding of conc. NH4OH. Each part was heated to 80 °C, cooled down and filtered to remove brownish precipitates. The golden yellow filtrate was heated to 80 °C with continued stirring and 12 mL of 5 % calcium chloride solution was put in. The solution was left overnight at 4 °C, centrifuged at 2500 rpm for 5mins, and precipitates were dissolved in 20 mL of H2SO4 (20 %). The total filtrates were titrated against 0.05 M KMnO4 solution to produce pink color that lasted for 30 s.

4.3 Determination of phytate

Phytate was verified by the described method of (Borquaye et al., 2017). Approximately 4 g of sample powder was taken and 100 mL 2 % HCl was added and constantly shaken for 3 h and filtered. To achieve the desired acidity, 30 mL filtrates were mixed with 6 mL of 0.3 % ammonium thiocyanate (NH4 SCN) as an indicator, followed by 50 mL water. The mixture was then titrated against a ferric chloride (FeCl3) solution of 0.00195 g/mL until the appearance of determined brownish yellow color as the end point. Phytate contents were determined using the equation below;

% Phytate = Titre value × 100 /1000 × sample mass

4.4 Statistical analysis

The average and standard deviations were used to express the results of the calculated data in each experiment. The significance of the means, standard deviations and standard curve were assessed using MS Excel software. The linear regression method was used to calculate the inhibitory concentrations (IC50). Tukey's multiple comparison tests using SPSS software determined the significant differences (P < 0.05) between means.

5 Results

5.1 Phytochemical analysis

The phytochemicals analysis of bark and leaves of Berberis baluchistanica specified the occurrence of Flavonoids, Tannins, Quinones, Anthraquinones, Saponins, Steroids, Alkaloids, Coumarin, Terpenoids and Phlobatannins in bark but cardiac Glycosides were absent whereas leaves contained all phytochemicals except Phlobatannins (Table 1). Note: Positive = present and Negative = absent.

S. No

Phytochemical test

Berberis baluchistanica parts

Bark

Leaves

1.

Alkaloids

Positive

Positive

2.

Anthraquinones

Positive

Positive

3.

Tannins

Positive

Positive

4.

Cardiac Glycosides

Negative

Positive

5.

Quinones

Positive

Positive

6.

Flavonoids

Positive

Positive

7.

Saponins

Positive

Positive

8.

Coumarin

Positive

Positive

9.

Terpenoids

Positive

Positive

10.

Steroids

Positive

Positive

11.

Phlobatannins

Positive

Negative

5.2 Total phenolics contents (TPC)

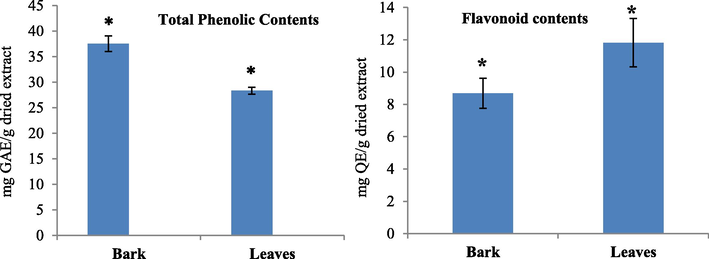

Total phenolics contents of bark and leaves extract of Berberis baluchistanica were analyzed by Folin–Ciocalteu (FC) process. According to the obtained results the TPC values were higher in bark than the leaves extract. The TPC value of the bark extract was 37.52 ± 1.56 mg GAE/g and that of leaves was 28.32 ± 0.66 mg GAE/g. Statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) were noted in the mean Phenolics Contents of the bark and leaves extract (Table 2) (Fig. 1). Note: Results are expressed as Mean ± S.D for three readings. Significant (p < 0.05) differences between groups are indicated by *.

Samples

Total phenolics

(mg GAE/g dry sample)

Total flavonoid

(mg QE/g dry sample)

Bark

37.52* ± 1.56

8.68*± 0.93

Leaves

28.32* ± 0.66

11.81* ± 1.49

Total phenolics contents expressed as mg GAE/g and Total Flavonoid contents expressed as mg QE/g of dried extracts of the bark and leaves of Berberis baluchistanica. Bars represent the standard deviations of means. Significant (p < 0.05) differences between groups are indicated by *.

5.3 Total flavonoid contents (TFC)

The Aluminium chloride colorimetric technique was used to evaluate the total flavonoid content of the extracts using Quercetin as standard. The total Flavonoid Content in bark and leaves were 8.68 ± 0.93 and 11.81 ± 1.49 mg QE/g respectively. The significant differences (P < 0.05) were noted in the mean Flavonoid Contents of the bark and leaves extract (Table 2) (Fig. 1).

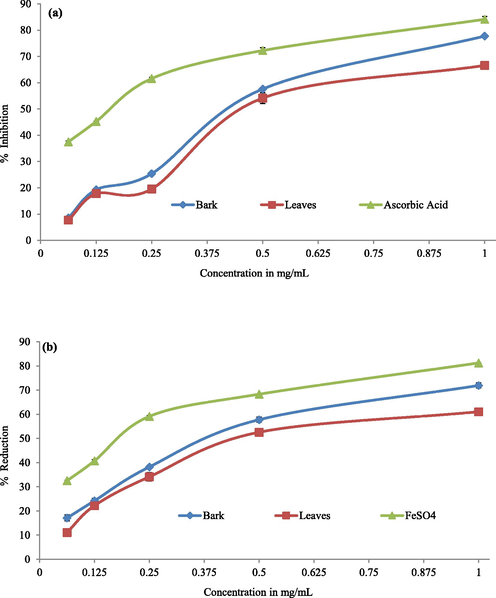

5.4 DPPH free radicals scavenging activity

The free radicals scavenging ability of the bark and leaves extracts of Berberis baluchistanica was assessed by the concentrations with 50 % inhibition (IC50) and results were obtained using a regression equation that plotted extract concentrations against scavenging capacity. The mean potential of each extract was found to increase linearly with concentration as shown in Fig. 2(a).

(a) Free radical scavenging activity (DPPH) (b) Ferrous reducing capacity (FRAP) of ethanolic extracts of the bark and leaves of Berberis baluchistanica. Each value is the mean ± standard deviation. Ascorbic acid and ferrous sulfate (FeSO4) were used as a standard in DPPH and FRAP.

The higher IC50 value specifies lower antioxidant effect and same for radical scavenging activity. The IC50 value of ascorbic acid was 0.325 mg/mL. The smallest IC50 value 0.678 mg/mL was determined to have the highest antioxidant potential in bark extract and leaves with IC50 value 0.785 mg/mL having lowest antioxidant value. The IC50 value of the bark extracts was relatively near to standard presented in Table 3.

Samples

DPPH Assay

(IC50 mg/mL)

FRAP Assay

(IC50 mg/mL)

Bark

0.678

0.871

Leaves

0.785

0.996

Ascorbic acid (Standard)

0.325

–

FeSO4(Standard)

–

0.472

5.5 Ferric reducing antioxidant power activity

The ability of Berberis baluchistanica bark and leaves extracts to convert Fe3 + into Fe2 + at 50 % inhibition (IC50), the needed concentration of extract, was used to check the antioxidant capacity of the samples. The results were calculated using a linear regression equation that plotted extract concentrations against their percent reduction ability. Bark extract, which has the strongest antioxidant potential, had the lowest IC50 value (0.871 mg/mL), while leaves with IC50 value of 0.997 mg/mL, and had the lowest antioxidant potential. The IC50 values of the bark extract were relatively near to the standard (Table 3). With increasing concentration, each extract's reduction power increased shown in Fig. 2(b).

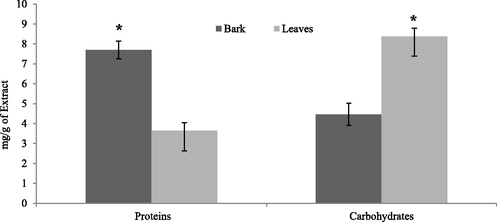

5.6 Total protein and carbohydrates

Total protein content in bark and leaves were analyzed by Lowry’s method. To build the calibration curve, the absorbance was quantified at various BSA concentrations. Total proteins of the bark and leaves extracts were 7.69 ± 0.65 mg BSAE/g and 3.63 ± 0.54 mg BSAE/g respectively (Table 4). Note: BSAE/g = Bovine Serum Albumin equivalent per gram, GE/g = Glucose Equivalent per gram. Significant (p < 0.05) differences between groups are indicated by *.

Samples

Nutrients

Antinutrients

Total Proteins

(mg BSAE/g) ± SD

Total Carbohydrates

(mg GE/g) ± SD

Oxalates(mg/g) ± SD

Phytate (%)

Bark

7.69*± 0.65

4.46*± 0.55

0.12 ± 0.02

0.17 ± 0.24

Leaves

3.63*± 0.54

8.38*± 0.71

0.14 ± 0.19

0.25 ± 0.08

Using glucose as the reference, the phenol sulphuric reagent activity was used to estimate the amount of carbohydrates. Total carbohydrate content of the bark and leaves extracts were 4.46 ± 0.55 mg GE/g and 8.38 ± 0.71 mg GE/g correspondingly. Statistically significant difference (P < 0.05) was noted in the mean Protein and Carbohydrate contents of the bark and leaves extract (Table 4) (Fig. 3).

Total Proteins and Carbohydrate contents (mg/g) of the bark and leaves of Berberis baluchistanica. Bars represent the standard deviations of means. Significant (p < 0.05) differences between groups are indicated by *.

6 Antinutrients analysis

6.1 Determination of oxalate

The antinutrients components of bark and leaves were evaluated in terms of oxalate analysis and compared. The oxalate contents of bark were 0.12 ± 0.02 mg/g and leaves were 0.14 ± 0.19 respectively. However, no significant difference (P > 0.05) was noted in the mean oxalate contents of the bark and leaves extract (Table 4).

6.2 Determination of phytate

The antinutrients components of bark and leaves were appraised in terms of Phytate % and results were presented in (Table 4). The phytate % composition of bark was 0.17 ± 0.24 % and leaves were 0.25 ± 0.08 % respectively. According to obtained results, no significant differences (P > 0.05) were noted in phytate composition of the bark and leaves extracts.

7 Discussion

A significant source of effective and specialized medications is natural substances for severe diseases. In all developing world where access to basic healthcare is limited, using herbal remedies has become a prevalent practice. The identification of bioactive substances begins with a phytochemical investigation (Edrah et al., 2013). The amount of bioactive compounds in plants has been directly linked to its biological actions. In present study all the identified compounds are recognized to comprise a broad range of biological actions (Uddin et al., 2021). The occurrence of these bioactive components gives support to its use by the local population, and the identification of novel medicinal components will help researchers for better understanding the beneficial properties of chemicals found in medicinal plants (Pervez et al., 2019). Phenolic and flavonoid compounds found in medicinal plants have made known to have antispasmodic, anticancer, antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, antidepressant and antioxidant power by having redox properties (Gul et al., 2022a, 2022b). The neutralization and scavenging of free radicals are accomplished by phenolic chemicals, which also control plant cell division, growth, and metabolic processes. Numerous enzymes, including alkaline phosphatases, hydrolases, cAMP phosphodiesterase, lipase, and -glucosidase, are inhibited by flavonoids (Iqbal et al., 2020). The antioxidant responses of phenolics and flavonoids varies depend on their chemical structures and other chemical constituents of the extract (Ng et al., 2021). Total phenolic contents value of the bark extract was 37.52 ± 1.56 mg GAE/g and that of leaves was 28.32 ± 0.66 mg GAE/g, and the total flavonoid contents in bark and leaves were8.68 ± 0.93 and 11.81 ± 1.49 mg QE/g respectively as displayed in (Table 2). Due to the considerable amounts of phenolics and flavonoids found in the bark and leaf extracts, this plant may have been utilized in a number of traditional medicines because of its potent antioxidant capabilities. Earlier, different fractions were used to calculate the bioactive components of the entire Berberis baluchistanica. The achieved total phenolics content values of bark and leaves in recent study were in agreement with the previous results (Abbasi et al., 2013). However, the obtained results of current study were propositionally lower as reported earlier (Uddin et al., 2021). There are numerous variables that can affect the quantities of phenolic compounds, including geographic location, environmental conditions, climatic processes, growing season, the type of soil, and storage and processing conditions (Gul et al., 2022a, 2022b). The high phenolics and flavonoids content are the reasons for the bioactivity of the crude extract. Flavonoids are very effective at removing oxidizing molecules including various free radicals associated with a number of diseases. Phenolics contents supply the oxidative stress tolerance in plants. Herbs, fruits, vegetables and other plant materials rich in phenolics and flavonoids are utilized in the food industries due to their anti-oxidative properties and health benefits (Ghafoor et al., 2020).

One of the most reliable methods for determining how well plant extracts can scavenge free radicals is the DPPH assay. Strong oxidant DPPH requires an extra electron to transform into a stable element (Abbasi et al., 2013). The higher IC50 values indicate low antioxidant effect and similar for radical scavenging activity. The smallest IC50 value 0.678 mg/mL was recorded for bark extract and leaves with IC50 value 0.785 mg/mL having lowest antioxidant effect. The IC50 value of bark extracts was comparatively close to that of the standard. All the selected parts of the plant showed considerably different antioxidant potentials of scavenging DPPH free radicals and decreased order was found as bark > leave. The content of phenolic and flavonoid compounds in the sample is typically correlated with the antioxidant power of plant extracts. Higher antioxidant activity is described by a higher amount of poly phenolics (Belwal et al., 2020). A positive tendency between total phenolics contents and the antioxidant power of the extracts in terms of radical scavenging activity (IC50) was observed. Higher amount of phenolics compounds present in bark supported the higher antioxidant potential of bark extract. Results attained are better than those of the entire Berberis baluchistanica plant as reported by (Abbasi et al., 2013).

The antioxidant potential of Berberis baluchistanica bark and leaves against reactive oxygen species was evaluated using the FRAP assay. The antioxidants have the ability to donate electrons and convert Fe3 + into Fe2 +. The Fe2 + and tripyridyltriazine complexes produce a strong blue color with a high absorption at 595 nm. The IC50 values of the extracts are correlated with their antioxidant capacity. Poorer lowering activity or lower antioxidant capability are indicated by greater IC50 values. The results showed that the ethanolic bark extract had the lowest IC50 (0.871 mg/mL) and the highest FRAP% reduction values than leaves IC50 (0.997 mg/mL) and lower than the IC50 (0.472 mg/mL) of standard. The results were calculated using a linear regression equation that plotted extract concentrations against their percent reduction ability. The reducing power of each extract increased with increase in concentration as shown in Table 3, Fig. 2(b). Results are in conformity with previous data (El-Zahar et al., 2022). By using Lowry's method and the phenol sulphuric process, the total protein and total carbohydrate contents were evaluated. The most generally used technique for calculating the amount of protein present in any biological sample is Lowry's method, which estimates the total protein content. Even very low protein concentrations can be detected using this technique. The reaction between peptide nitrogen and copper in an alkaline setting serves as the foundation for the Lowry technique of calculating protein concentrations. Total proteins of the bark and leaves extracts were 7.69 ± 0.65 mg BSAE/g and 3.63 ± 0.54 mg BSAE/g respectively. Total carbohydrate contents of the bark and leaves extracts were 4.46 ± 0.55 mg GE/g and 8.38 ± 0.71 mg GE/g respectively as presented in (Table 4). A significantly higher mean proteins content was observed in bark compared to leaves. On the other side, significantly higher mean carbohydrates content was observed in leaves compared to bark. The latest study emphasized the importance of plant proteins for human nutrition. Plant protein is now employed as a substitute protein source in everyday life. There is a wide range in how much plant proteins contribute to the availability and consumption of total dietary protein among populations, both in the developed world and elsewhere (Sarkar et al., 2020). The major protein and carbohydrate obtained from plants is essential since it is readily available, inexpensive, or low cost with nearly no adverse effects. It may be said that plant protein and carbohydrate combinations can offer a full, essential, and balanced source of amino acids and sugars that successfully satisfies human physiological needs (Ghosh et al., 2020).

Researchers have long been concerned about the potential negative health impacts of therapeutic plants due to concerns that they contain anti-nutrients. Oxalate is a chemical compound found in many regularly eaten plant foods. These substances are produced in small amounts in both animals and plants. Along with sodium, potassium, calcium, iron, and magnesium, it creates insoluble salts. Absorbed oxalates may inhibit the absorption of calcium and increase the creation of calcium kidney stone due to which oxalates are considered as antinutrients. Phytate or phytic acid is the chief phosphorus storage compound in plants. According to reports, excessive dietary phytate content inhibits growth and reduces food value through binding (Idris et al., 2019). This prevents mineral ions from being available to consumers, and high phytate content have been linked to negatively affect some protein and lipid utilization in the body by creating complexes with them as well as the absorption and digestion of several minerals. This is possible because of its tendency to form insoluble salts by chelating with cations like magnesium, calcium, iron, zinc, potassium, and copper. On the other hand, low plant phytate concentrations would be useful from a nutritional standpoint (Rehman and Adnan, 2018). When compared to a meal high in phytate (10–60 mg/g), which has been shown to reduce the bioavailability of minerals in animals when ingested over an extended period of time, the phytate composition of the sample may not offer any health risks (Badu et al., 2020).

8 Conclusion

The outcomes obtained demonstrated that extracts of Berberis baluchistanica bark and leaves are abundant in various bioactive components that have the potential to function as antibacterial, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory agents. The extracts were found to have a significant amount of phenolic and flavonoid contents with strong antioxidant potential. The evaluation of the protein and carbohydrate content reveals that it comprises inexpensive, easily accessible proteins and carbohydrates. New discoveries suggest that the Berberis baluchistanica plant might be a useful resource of active medications due to the occurrence of potent bioactive compounds with strong biological potentials. It has also been confirmed in this study that the antinutrients in the B. baluchistanica bark and leaves are in the acceptable range, that is value addition to be used as a traditional folk medicine.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Zareen Gul: Writing – original draft. Ali Akbar: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. Mahrukh Naseem: Resources. Jahangir Khan Achakzai: Resources. Zia Ur Rehman: Resources. Nazir Ahmad Khan: Resources.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Berberis baluchistanica assdesment of natural antioxidant to reprieve from oxidative stress. Int. Res J. Pharm. 2013;4(5):101-105.

- [Google Scholar]

- A comprehensive appraisal of the wild food plants and food system of tribal cultures in the hindu kush mountain range; a way forward for balancing human nutrition and food security. Sustainability. 2021;13(9):5258.

- [Google Scholar]

- Functional, antioxidant, antimicrobial potential and food safety applications of curcuma longa and cuminum cyminum. Pak. J. Bot. 2019;51(3):1129-1135.

- [Google Scholar]

- Proximate composition, antioxidant properties, mineral content and anti-nutritional composition of sesamum indicum, cucumeropsis edulis and cucurbita pepo seeds grown in the savanna regions of ghana. J. Herbs Spices Medicinal Plants. 2020;26(4):329-339.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phytochemical and biological screening of root extracts of berberis baluchistanica. BioCell. 2019;43(2)

- [Google Scholar]

- Determination of phenolic compounds and antioxidant activities of 55 iranian berberis genotypes. J. Medicinal Plants By-product 2022

- [Google Scholar]

- Phytopharmacology and clinical updates of berberis species against diabetes and other metabolic diseases. Front. Pharmacol.. 2020;11:41.

- [Google Scholar]

- The ferric reducing ability of plasma (frap) as a measure of “antioxidant power”: The frap assay. Anal. Biochem.. 1996;239(1):70-76.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nutritional and anti-nutrient profiles of some ghanaian spices. Cogent Food Agric.. 2017;3(1):1348185.

- [Google Scholar]

- Preliminary phytochemical screening and antibacterial activity of pistacia atlantica and prunus persica plants of libyan origin. Int. J. Sc Res.. 2013;4(2):1552-1555.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antioxidant, antibacterial, and antifungal activities of the ethanolic extract obtained from berberis vulgaris roots and leaves. Molecules. 2022;27(18):6114.

- [Google Scholar]

- Investigation of the pharmacological properties of lepidagathis hyalina nees through experimental approaches. Life. 2021;11(3):180.

- [Google Scholar]

- Total phenolics, total carotenoids, individual phenolics and antioxidant activity of ginger (zingiber officinale) rhizome as affected by drying methods. Lwt. 2020;126:109354

- [Google Scholar]

- Phytochemical composition analysis and evaluation of in vitro medicinal properties and cytotoxicity of five wild weeds: a comparative study. F1000Research 2020:9.

- [Google Scholar]

- High throughput screening for bioactive components of berberis baluchistanica ahrendt root and their functional potential assessment. BioMed. Res. Int. 2022

- [Google Scholar]

- Elucidating therapeutic and biological potential of berberis baluchistanica ahrendt bark, leaf, and root extracts. Front. Microbiol.. 2022;13:823673.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of the proximate composition, vitamins (ascorbic acid, α-tocopherol and retinol), anti-nutrients (phytate and oxalate) and the gc-ms analysis of the essential oil of the root and leaf of rumex crispus l. Plants. 2019;8(3):51.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phytogenic synthesis of nickel oxide nanoparticles (nio) using fresh leaves extract of rhamnus triquetra (wall.) and investigation of its multiple in vitro biological potentials. Biomedicines. 2020;8(5):117.

- [Google Scholar]

- Berberis aristata and its secondary metabolites: Insights into nutraceutical and therapeutical applications. Pharmacol. Res.-Modern Chinese Medicine. 2022;100184

- [Google Scholar]

- Nutritional, phytochemical potential and pharmacological evaluation of nigella sativa (kalonji) and trachyspermum ammi (ajwain) J. Medicinal Plants Res.. 2012;6(5):768-775.

- [Google Scholar]

- Screening of antibacterial activity of four medicinal plants of balochistan-pakistan. Pak. J. Bot. 2012;44:245-250.

- [Google Scholar]

- Protein measurement with the folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem.. 1951;193:265-275.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of in vitro, in silico antidiabetic and antioxidant potential of bioactivity based isolated “pakistanine” from berberis baluchistanica. Arabian J. Chem.. 2022;15(11):104221

- [Google Scholar]

- Quantitative ethnomedicinal status and phytochemical analysis of berberis lyceum royle. Agronomy. 2021;11(1):130.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparative analyses on radical scavenging and cytotoxic activity of phenolic and flavonoid content from selected medicinal plants. Natural Product Res.. 2021;35(23):5271-5276.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial and antioxidant potential of berberisinol, a new flavone from berberis baluchistanica. Chem. Natural Compounds. 2019;55(2):247-251.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nutritional potential of pakistani medicinal plants and their contribution to human health in times of climate change and food insecurity. Pak. J. Bot. 2018;50(1):287-300.

- [Google Scholar]

- Screening of phytochemicals and in vitro evaluation of antibacterial and antioxidant activities of leaves, pods and bark extracts of acacia nilotica (l.) del. Ind. Crops Products. 2015;77:873-882.

- [Google Scholar]

- Traditional uses of some useful medicinal plants of ziarat district balochistan, pakistan. FUUAST J. Biol.. 2013;3(1 june):101-107.

- [Google Scholar]

- Quantification of total protein content from some traditionally used edible plant leaves: a comparative study. J. Medicinal Plant Stud.. 2020;8(4):166-170.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparative analysis of antioxidant activity, toxicity, and mineral composition of kernel and pomace of apricot (prunus armeniaca l.) grown in balochistan, pakistan. Saudi J. Biol. Sci.. 2021;28(5):2830-2839.

- [Google Scholar]

- Green synthesis of nickel oxide nanoparticles from berberis balochistanica stem for investigating bioactivities. Molecules. 2021;26(6):1548.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bioprospecting roots, stem and leaves extracts of berberis baluchistanica ahrendt. (berberidaceae) as a natural source of biopharmaceuticals. Journal of Taibah University for. Science. 2022;16(1):954-965.

- [Google Scholar]

- Berberis kansuensis extract alleviates type 2 diabetes in rats by regulating gut microbiota composition. J. Ethnopharmacol.. 2021;273:113995

- [Google Scholar]

Appendix A

Supplementary material

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2022.102517.

Appendix A

Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article: