Nucleotide analysis and prevalence of Escherichia coli isolated from feces of some captive avian species

⁎Corresponding author. mohsin.bukhari@uvas.edu.pk (Syed Mohsin Bukhari)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

The aim of the study was to check the prevalence of Escherichia coli in some captive avian species, seasonal effect on the E.coli prevalence and analysis of nucleotide sequences of E.coli. A total of 132 samples, 33 from Turkey (Meleagris gallopavo), 33 form Pheasant (Phasianus colchicus), 33 from Budgerigar (Melopsittacus undulates) and 33 from Chukar partridge (Alectoris chukar) were collected from Conservation and Research Center, UVAS, Ravi Campus, Pattoki. Colony forming units was quantified for each sample. E. coli confirmation was done by biochemical and molecular characterization. 16S rRNA was amplified and sequenced. 16S rRNA sequence was submitted to NCBI under the accession number MN841017, MN841018 and MN841019.Descriptive statistics showed the mean ± SEM value for E. coli CFU/ml of fecal sample from Turkey 1.91 × 108 ± 4.4 × 107, for Pheasants, the mean ± SEM was 1.55 × 108 ± 5.2 × 107 CFU/ml of fecal sample. The mean ± SEM of the fecal sample for Budgerigars and Chukar were 2.12 × 108 ± 3.3 × 107 CFU/ml and 1.6 × 108 ± 4.5 × 107 CFU/ml respectively. Inferential statistics showed that regardless of the bird species, there was almost a similar frequency of E. coli CFU/ml of fecal sample (p = 0.74). However, the incidence of E. coli fluctuates significantly depending on the season in the case of turkey and pheasants, and the impact was statistically significant (p < 0.0005). E.coli was most prevalent in Turkey during rainy summer and in Pheasants during cool dry winter. These findings show that accidental or direct contact with feces of these captive birds have possible risk of gastric illness to humans and animals. Furthermore, understanding the mechanisms driving the seasonality of this important zoonotic pathogen will allow for the execution of effective control strategies when it is most prevalent.

Keywords

Captive avian species

Escherichia coli

Prevalence

Fecal sample

16S rRNA gene

1 Introduction

Captive avian species refers to those bird species that are kept in cages, aviary or in a confined environment. These avian species may be kept as pets (Dipineto et al. 2017), as source of income (Ombugadu et al. 2019), as a source of recreation for human especially for children or may be for captive breeding (Heinrichs et al. 2019). For captive breeding or conservation, the areas in use are zoos, private or government state agencies, private breeding farms, conservation foundations and research centers that exist inside or may be outside the universities (Ombugadu et al. 2019).

Zoo visitors and pet owners are more in danger of acquiring zoonotic diseases from cage birds and their companion birds (Conrad et al. 2017). The zoonotic disease transfer from diseased or carrier birds can either be direct or indirect. Direct mode of transmission includes direct bird to bird contact (Dipineto et al. 2017). While indirect transmission includes contact with their fecal material, saliva, nasal discharge, feathers (Miskiewicz et al. 2018) or by the fomites, such as bedding, panels and even the cages.

The most common candidate of zoonotic disease transfer from cages to visitors is bacteria (Conrad et al. 2017; de Oliveira et al. 2018). In tropical countries, Psittacine birds have been proved as the potential source of diarrheagenic Escherichia coli. These pathogens are linked with mortality of children (Conrad et al. 2017).

Family Enterobacteriaceae includes six species and out of all E. coli is the most efficient and opportunistic candidate in captive animals (Walk et al. 2009). It was initially known as harmless commensal but with the passage of time E.coli afforded an alternate site through gene gain and loss and become a highly diverse and adapted pathogen (Croxen and Finlay, 2010). E.coli has following types of enteric pathotypes: Enteropathogenic E.coli (EPEC), Shiga toxin-producing E.coli (STEC), Enteroinvasive E.coli (EIEC), Enteroaggregative E.coli (EAEC), Enterotoxigenic E.coli (ETEC), Diffusely Adherent E.coli (DAEC) and Adherent-invasive E.coli (AIEC) (Croxen et al. 2013). All these pathotypes have different specific hosts and causes diarrhea in individuals of certain age groups (Croxen et al. 2013). External contact and ingestion of food contaminated with fecal bacteria is the source of zoonoses and illness (Mirsepasi-Lauridsen et al. 2019).

Captive birds cause direct or indirect human exposure to avian microbes. Fecal microbes i.e, E.coli are the potential source of avian species mortality (Ewers et al. 2003; Kiliç, et al. 2007) and human illness (Mirsepasi-Lauridsen et al. 2019). Avian pathogenic Escherichia coli is economically dangerous and affects poultry worldwide. Septicemia, omphalitis, swollen head syndrome, cellulitis, pericarditis, perihepatitis, yolk sac infection, or a combination of these disorders can all be caused by avian colibacillosis (Kabir, 2010). Solà-Ginés et al. (2012) found that avian pathogenic Escherichia coli strains cause a 2–3 % decline in egg production and a 3–4 % increase in bird mortality on a farm. Some of the signs and symptoms include subacute pericarditis, acute fatal septicemia, salpingitis, airsacculitis, cellulitis and peritonitis. The present study has been designed to check the E.coli prevalence in fecal material of captive avian species, effect of seasonality on the prevalence and to analyze the nucleotide sequence of fecal E.coli.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Collection of fecal samples

Fecal sample were collected within 1 h of deposition from healthy birds, thrice a month from July 2018 to June 2019, from the captive Pheasant (Phasianus colchicus), Chukar partridge (Alectoris chukar), Budgerigar (Melopsittacus undulates) and Turkey (Meleagris gallopavo) reared privately at Avian Conservation and Research Center, Department of Wildlife and Ecology, University of Veterinary and Animal Sciences, Ravi Campus, Pattoki, Pakistan. The map of the study site shown in Fig. 1. Fecal sample was collected from the ground of cages following the method of Garcia-Mazcorro et al., (2017). During fecal sample collection no direct contact with the captive birds was made. Because birds are frequently reared together in captivity, an aggregate of feces per flock was collected.

- Farm location in which the samples were collected.

Fecal samples (5 g) were collected in sterilized falcon tube (10 ml) from the metallic tray and were stored at −20 °C until processed (Table 1).

| Sample ID | Bird species | No. of birds | Male: Female | Feeding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RP1 | Ring-necked Pheasant (Phasianus colchicus) | 4 | 1:3 | Seeds and grains |

| CP1 | Chukar partridge (Alectoris chukar) | 3 | 1:2 | Seeds and grains |

| BR1 | Budgerigar (Melopsittacus undulates) | 12 | 5:7 | Mix of seeds and fresh fruits |

| TR1 | Turkey (Meleagris gallopavo) | 4 | 1:3 | Seeds and grasses |

2.2 Processing of fecal samples

Fecal samples were dried (2 h at 40 °C) and ground into powder form. A 0.2 g of each powdered sample was mixed in 1 ml of PBS solution separately in proper labeled 1.5 ml Eppendorf tubes. Mixture was centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 5 min on Bio-Rad centrifuge machine (Murphy et al. 2005) and the supernatant of the centrifuged sample was serially diluted up to 10-6 folds (Jahan et al. 2018).

2.3 Prevalence, identification and molecular characterization of E.coli

The plate count method was used to determine the number of E.coli colonies per milliliter of the fecal sample using 200 µl of each dilution on MacConkey agar (Jahan et al. 2018). Culture plate with colonies within 30–300 was considered for the calculation of CFU (Sutton, 2011).

Number of cells/ml = colonies counted / volume plated × dilution.

For conformation of E.coli three putative E. coli colonies from each plate were individually identified by cultural characteristics and conventional biochemical tests following Cheesbrough (1985). QIAGEN amp Bacterial Genomic Extraction kit was used to extract DNA from pure culture of E.coli. DNA presence and concentration were checked through Agarose Gel electrophoresis and NanoDrop 2000 and 2000c Thermo Scientific™. A fragment of the 16S rRNA region of bacterial DNA was amplified using the predesigned universal primers FP 5′-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′ RP5′- CTTGTGCGGGCCCCCGTCAATTC-3′primers (Magray et al. 2011).

BIO RAD PCR Gradient machine was used for the amplification. QIA-quick PCR purification kit (28704; Qiagen, West Sussex, UK) was used for the purification of amplicons. Purified products were sent for genomics and sequencing analysis to Novagene Bioengineering Company.

2.4 Statistical analysis

Two-way ANOVA was used to examine the effect of season and type of host species on the prevalence of E.coli.

The partial gene sequences of pathogenic strains were edited by using BioEdit 7.2. and compared using BLAST against the public database available in gene bank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and Mega 7.0.2. Software was used for analyzing the genomics and sequence data. Identification of strains was based on similarity and dissimilarity of nucleotides (Suardana, 2014). All sequences were submitted to NCBI GenBank for accession numbers.

3 Results

3.1 E.coli enumeration by viable count from collected sample

Descriptive statistics shows the mean ± SEM value 1.91 × 108 ± 4.4 × 107 for E.coli CFU/ml of fecal sample of Turkey. For Pheasants, the mean ± SEM is 1.55 × 108 ± 5.2 × 107 CFU/ml of fecal sample. Budgerigars and Chukar showed the mean ± SEM 2.12 × 108 ± 3.3 × 107 CFU/ml and 1.6 × 108 ± 4.5 × 107 CFU/ml of fecal sample respectively.

Two-way ANOVA showed that there is no statistically significant effect of type of specie on E.coli CFU/ml of fecal sample as p = 0.73 as shown in Table 2. However, CFU/ml of fecal sample varies greatly with respect to season and the effect was statistically significant p < 0.0005 only in turkey and pheasants.

| Species | Season | CFU ± SEM | P value | CFU ± SEM | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turkey | Rainy summer | 4.1 × 108 ± 6.8 × 107 | 0.0001* | 1.91 × 108 ± 4.4 × 107 | 0.739 |

| Monsoon | 9.3 × 107 ± 9.2 × 107 | ||||

| Cool Dry winter | 1.2 × 108 ± 6.5 × 107 | ||||

| Hot Dry summer | 3.9 × 107 ± 7.3 × 107 | ||||

| Pheasant | Rainy summer | 3.7 × 108 ± 7.3 × 107 | 0.0001* | 1.55 × 108 ± 5.2 × 107 | |

| Monsoon | 3.3 × 108 ± 8.4 × 107 | ||||

| Cool Dry winter | 9.5 × 108 ± 6.5 × 107 | ||||

| Hot Dry summer | 7.3 × 107 ± 7.3 × 107 | ||||

| Budgerigars | Rainy summer | 2.8 × 108 ± 7.3 × 107 | 0.118 | 2.12 × 108 ± 3.3 × 107 | |

| Monsoon | 1.8 × 108 ± 8.4 × 107 | ||||

| Cool Dry winter | 9.4 × 106 ± 6.5 × 107 | ||||

| Hot Dry summer | 1.5 × 108 ± 7.3 × 107 | ||||

| Chukar | Rainy summer | 3.1 × 108 ± 6.8 × 107 | 0.137 | 1.6 × 108 ± 4.5 × 107 | |

| Monsoon | 9.0 × 107 ± 8.4 × 107 | ||||

| Cool Dry winter | 5.3 × 107 ± 6.5 × 107 | ||||

| Hot Dry summer | 1.8 × 108 ± 7.3 × 107 |

Note: “*” shows significant difference at (p < 0.001).

3.2 Identification of E.coli

E.coli showed different cultural characteristics on different media as shown in Table 4. Biochemical tests were performed for the putative E.coli colonies isolated from fecal sample on MacConkey agar. Results are shown in Table 4.

3.3 Molecular characterization of E.coli

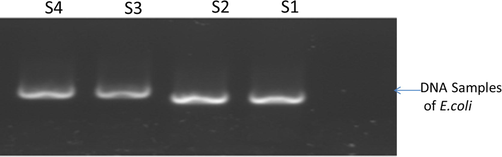

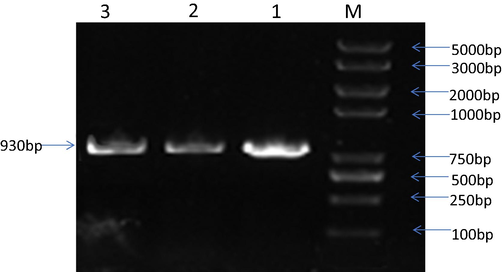

E.coli Genome obtained as shown in Fig. 2 was used as a template for the identification and amplification of 16S gene (930 bp fragment) by using universal pair of primers. The PCR amplification product was run on gel for the confirmation of PCR shown in Fig. 3. Sequenced data was edited, BLAST and submitted to the NCBI for attaining accession numbers shown in Table 3.

- Analysis of target DNA, extracted from pure culture of E.coli by QIAGEN amp Bacterial Genomic Extraction Kit.

- Lane 1–3 confirmation of 16S rRNAgene by PCR amplification with FP 5′-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′RP5′- CTTGTGCGGGCCCCCGTCAATTC-3′primers. M: DNA marker Trans 2 K.

| Sequence_ID | Organism | strain | Collection Date | Isolation source | Accession number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nimkp01-19 | E. coli | nimkp01-19 | 29-Jan-2019 | fecal sample of a captive Phasianus colchicus | MN841017 |

| nimkb02-19 | E. coli | nimkb02-19 | 03-April-2019 | fecal sample of a captive Melopsittacus undulatus | MN841018 |

| nimkt03-19 | E. coli | nimkt03-19 | 06-Feb-2019 | fecal sample of a captive Meleagris gallopavo | MN841019 |

4 Discussion

E.coli isolates from fecal samples of the apparently healthy avian species (Phasianus colchicus, Alectoris chukar, Melopsittacus undulates and Meleagris gallopavo) were grown on previously recommended (Buxton and Fraser, 1977; Cowan, 1985; Cheesbrough, 1985) media. E.coli were isolated and identified based on colony morphology by using MacCokey agar and EMB agar shown in Table 4. Parallel findings were stated by former workers (Boro et al. 2018; Kar et al. 2017). Biochemical characteristics exhibited by the E.coli coincides with the discoveries of other researchers (Boro et al. 2018; Elafify et al. 2016).

| Serial no | Tests and Media used | Results |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nutrient agar | Big, mucoid colonies of off-white/ milky white color appeared |

| 2 | MacConkey agar | Large mucoid rose-pink colored colonies with somehow darker center |

| 3 |

EMB agar |

Dark colored circular colonies showing metallic sheen of green color |

| 4 | LB Broth | Equally and smoothly dispersed growth |

| 5 | Gram staining | Gram negative, short bacilli |

| 6 | Motility | + |

| 7 | Lactose Fermentation | + |

| 8 | Endospore staining | – |

| 9 | Catalase test | + |

| 10 | Oxidase | – |

| 11 | MR (Methyl Red) | + |

| 12 | VP (Voges–Proskauer) | – |

| 13 | Glucose Fermentation | + |

| 14 | Fructose fermentation | – |

Present study was an attempt to compare the E.coli prevalence in four important captive avian species and seasonal effect on E.coli prevalence. All the fecal samples analyzed were positive for E.coli. and it was concluded that E.coli prevalence doesn’t depend upon the type of the species because the difference between mean of CFU/ml of the E.coli was non-significantly different from others showing p-value > 0.05. E.coli prevailed in species as budgerigars > turkey > Chukar > Pheasants. The prevalence of E.coli was higher in budgerigar’s fecal material than other species.

Effect of seasonal variation on the prevalence of E.coli was checked through examine the fecal sample from the same population thrice per month from July-2018 to May- 2019. In Pakistan there are total four seasons and the division of months were made according to (Blood, 1996) climate of Pakistan. Statistical analysis showed that season effected E.coli prevalence in each species differently. Seasonal effect on the prevalence of E.coli in captive avian species has not been reported before and it was observed in present study that E.coli prevalence is more in rainy summer than the winter. The reason might be temperature, humidity, and the type of food.

Neher et al. 2016 also isolated the E.coli from the 16/25 samples of fecal, oral, and gut of healthy bird species and concluded that even the healthy avian species could be a source of E.coli. Present findings are also supported by Sarker et al. 2012 who isolated the different pathogenic species from the fecal sample of healthy water birds and found E.coli as the most prevalent bacteria. E.coli from the healthy turkey (Kar et al. 2017) and psittacine (Gioia et al., 2016) has been reported also and it was concluded that these healthy birds are the carrier of vast range of E.coli either pathogenic or nonpathogenic and can be a risk to the sanitary condition and potential source of zoonoses. These findings are consistent with Bukhari et al. 2022 findings for next generation sequencing analysis of fecal material from two pheasant species, where the second most abundant phylum identified from fecal material was Proteobacteria, and E.coli belongs to this phylum.

E.coli inhibits the most animal intestine as natural intestinal flora, and it does not vary significantly from species to species. Though, the sampling population used in this study was inhibiting the same area throughout the study duration, this can also be the reason for having approximately same prevalence rate of E.coli in fecal samples. As stated above all the samples were positive for E.coli these findings contradict the findings of previous studies where E.coli was found only in 16 % (Gioia et al., 2016), 13.6 % (Graham and Graham, 1978), 14 % from private collected sample, 63 % from sample collected from zoo and 19 % samples collected from pet shop (Medani et al. 2008).

From the finding it can be stated that the captive avian species could be responsible for the pathogenic E.coli. Proper protective measure in captivating these avian species should be applied, and further research is needed to determine the strain type and virulence gene factors linked with these E.coli in order to develop better control strategies and preventive measures. E. coli ecology should also be investigated to establish whether they are actually part of the natural flora of birds or more reflective of the environment in which the birds reside.

5 Conclusion

It was concluded that captive birds are a reservoir of pathogenic E.coli that can be transmitted to humans and other animals. E.coli cause severe gastric illness individuals that consumed these birds. Furthermore, understanding the mechanisms driving the seasonality of this important zoonotic pathogen could be beneficial for the execution of effective control strategies when it is most prevalent.

6 Disclosure of funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowldgement

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Khalid University, Abha, Saudi Arabia for funding this work through Small Groups project under grant number RGP.1/227/43

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Pakistan: a country study. DIANE Publishing; 1996.

- Prevalence of Colibacillosis in birds in and around Guwahati city (Assam) J. Entomol. Zool. Stud.. 2018;6(1):1000-1003.

- [Google Scholar]

- Metagenomics analysis of the fecal microbiota in Ring-necked pheasants (Phasianus colchicus) and Green pheasants (Phasianus versicolor) using next generation sequencing. Saudi J Bio Sci.. 2022;29(3):1781-1788.

- [Google Scholar]

- Buxton, A., and Fraser, G., 1977. Animal Microbiology. Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford, London, Edinburgh, Melbourne, 1: 85-110.

- Cheesbrough, M., 1985. Medical laboratory manual for tropical countries 1st edi. Vol 2. Microbiology. English Language Book Society. London. p. 400-480.

- Farm fairs and petting zoos: A review of animal contact as a source of zoonotic enteric disease. Foodborne Pathog Dis.. 2017;14(2):59-73.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cowan and Steel’s Manual for the Identification Medical Bacteria (2nd edn.). Cambridge, London: Cambridge University Press; 1985. p. :96-98.

- Molecular mechanisms of Escherichia coli pathogenicity. Nat. Rev. Microbiol.. 2010;8(1):26.

- [Google Scholar]

- Recent advances in understanding enteric pathogenic Escherichia coli. Clin. Microbiol. Rev.. 2013;26(4):822-880.

- [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira, M. C., Camargo, B. Q., Cunha, M. P., Saidenberg, A. B., Teixeira, R. H., Matajira, C. E., Moreno, L. Z., Gomes, V. T., Christ, A. P., Barbosa, M. R., Sato, M. I., 2018. Free-Ranging Synanthropic Birds (Ardealba and Columba livia domestica) as Carriers of Salmonella spp. and Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli in the Vicinity of an Urban Zoo. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 18(1), 65-9.

- Campylobacter coli infection in pet birds in southern Italy. Acta Vet. Scand.. 2017;59(1):6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and molecular characterization of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli isolated from table eggs in Mansoura. Egypt. J Adv Vet Anim Res.. 2016;3(1):1-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Avian pathogenic Escherichia coli (APEC) Berl Munch Tierarztl Wochenschr.. 2003;116(9–10):381-395.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comprehensive molecular characterization of bacterial communities in feces of pet birds using 16S marker sequencing. Microb. Ecol.. 2017;73(1):224-235.

- [Google Scholar]

- Gioia-Di, Chiacchio, R. M., Cunha, M. P. V., Sturn, R. M., Moreno, L. Z., Moreno, A. M., Pereira, C. B. P., Martins, F. H., Franzolin, M. R., Piazza, R. M. F., Knöbl, T., 2016. Shiga toxin-producing E. coli(STEC): Zoonotic risks associated with psittacine pet birds in home environments. Vet. Microbiol.184, 27-30.

- Occurrence of Escherichia coli in feces of psittacine birds. Avian Dis.. 1978;1:717-720.

- [Google Scholar]

- Microbial assessment of different samples of ostrich (Struthio camelus) and determination of antimicrobial susceptibility profiles of the isolated bacteria. Asian J. Med. Biol. Res.. 2018;3(4):437-445.

- [Google Scholar]

- Avian colibacillosis and salmonellosis: a closer look at epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, control and public health concerns. Int. J. Environ. Res.. 2010;7(1):89-114.

- [Google Scholar]

- Isolation and identification of Escherichia coli and Salmonella sp. from apparently healthy Turkey. Int. J. Adv. Res.. 2017;4(6):72-78.

- [Google Scholar]

- Detection of the eaeA gene in Escherichia coli from chickens by polymerase chain reaction. Turkish J. Vet. Anim. Sci.. 2007;31(4):215-218.

- [Google Scholar]

- Identification of Escherichia coli through analysis of 16S rRNA and 16S–23S rRNA internal transcribed spacer region sequences. Bioinformation.. 2011;6(10):370.

- [Google Scholar]

- STUDIES ON SOME BACTERIAL ISOLATES AFFECTING BUDGERIGARS. Suez Canal Vet. Med. J.. 2008;13(1):37-48.

- [Google Scholar]

- Escherichia coli pathobionts associated with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin. Microbiol. Rev.. 2019;32(2):e00060-e00118.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bird feathers as potential sources of pathogenic microorganisms: a new look at old diseases. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2018;111(9):1493-1507.

- [Google Scholar]

- Genotypic characterization of bacteria cultured from duck faeces. J. Appl. Microbiol.. 2005;99(2):301-309.

- [Google Scholar]

- Isolation and characterization of Shiga toxigenic Escherichia coli of animal and bird origin by multiplex polymerase chain reaction. Vet. World.. 2016;9(2):123.

- [Google Scholar]

- Impact of Parasites in Captive Birds: A Review. Curr. Res. Environ. Appl. Mycol.. 2019;2019(1):2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diversity of multi-drug resistant avian pathogenic Escherichia coli (APEC) causing outbreaks of colibacillosis in broilers during 2012 in Spain. PLoS ONE. 2012;10(11):e0143191.

- [Google Scholar]

- Suardana, I. W., 2014. Analysis of nucleotide sequences of the 16S rRNA gene of novel E. colistrains isolated from feces of human and Bali cattle. J. Nucleic Acids, 2014, 7.

- Cryptic lineages of the genus Escherichia. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.. 2009;75(20):6534-6544.

- [Google Scholar]