Translate this page into:

New route: Convertion of coconut shell tobe graphite and graphene nano sheets

⁎Corresponding author. rikson@usu.ac.id (Rikson Siburian)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Abstract

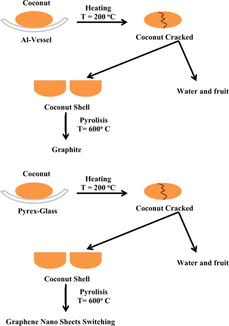

In this paper, we reported the simple way to generate both graphite and graphene nano sheets base on renewable natural resources (charcoal). The aims of this research are producing graphite and graphene nano sheets switching using simple way and to discuss the effect of vessel to properties of carbon. The research method concise of several steps: Step-1. The coconut as a raw material, we peeled coconuts to separate their fiber and shell, resulting coconut shell. Step-2. Each of coconut shell put on alumina (Al) vessel and glass vessel. Step-3. Both of them were cracked by using oven (T = 200 °C), resulting coconut water and coconut shell. Step-4. Each of coconut shell were pyrolized on tanur at T = 600 °C to generate charcoals. Step-5. Each of charcoal was analyzed by using X-ray diffraction (XRD). Interestingly, the properties of charcoal are totally different. There is effect of kind of vessel for carbon properties. While, coconut was on Al vessel, the resulting charcoal shows that the sharp peak appears at 2θ (27.8640 Å), indicating the graphite (C-sp3) is formed (XRD data). On the other hand, if we put coconut on the glass vessel, the charcoal converted tobe graphene nano sheets. It was clarified by the weak and broad peak at 2θ (23.64°). We concluded that we may produce directly graphite and also graphene by using simple method.

Keywords

Al-vessel

Glass-vessel

Graphite

Graphene nano sheets

1 Introduction

Graphene is a miracle material due to it has many superior properties. Production for a graphene application is a pivotal thing. This is caused production of graphene need strict requirements those are lowest grade, large scale, cheapest, sustainable and simple method (Novoselov, 2012). The majority method to produce graphene used graphite (Blake, 2008; Hernandez, 2008), and SiC (Forbeaux et al., 1998; Berger, 2004; Ohta, 2006) as raw materials. Recently, there are several methods to produce large scale graphene application, namely (i) mechanical (Novoselov, 2005); (ii) exfoliation of materials (Coleman, 2011); (iii) Chemical Vapour Deposition (CVD) (Li, 2009; Bae, 2010) and (iv) modification of graphene and producing of graphene sheets by using chemical (Elias, 2009; Nair, 2010; Liao, 2011; Boukhvalov and Katsnelson, 2009; Zhao, et al., 2011; Zhang, 2011; Vincent, 2009). Almost of large scale graphene production base on graphite as well as raw material.

Graphite is provided by nature, meaning It is only be produced from nature and unrenewable resources. Graphite may obtain by mining process. Unfortunately, graphite can not synthesize by laboratory. We need graphite and graphene. Recently, graphene is favour to generate by chemical method (Siburian and Kondo, 2018; Siburian and Nakamua, 2018; Siburian, 2018; Siburian and Sebayang, 2018; Siburian et al., 2018). That means graphite will be used as a raw material. How to overcome this serious problem. Our idea, we used coconut as a raw material. That is due to coconut is abundant resources and C-amorphous. The challenging is how to convert C-amorphous to be C-crystalin. Therefore, we prepared experimental base on coconut shell as a raw material. Interestingly, we may generate directly graphite and graphene nano sheets only one step (without using graphite, hard acid and strong oxidator). Our method is also cheap, abundance, renewable material, simple and using low temperature (green approaching)

2 Experimental

Briefly, the experiment is described as below:

-

We peeled off two coconuts to separate between fiber and coconut.

-

Then, one coconut was put on Al vesel and the other, it put on glass vessel.

-

After that, each of coconut was heated on 200 °C for 10 min by using oven, resulting the cracking coconut shell.

-

Subsequently, we separated between fruit and coconut shell, resulting coconut shell.

-

Each of coconut shell was pyrolized on 600 °C by tanur, resulting charcoal.

-

Finally, each of charcoal was characterized by using XRD.

3 Results and discussion

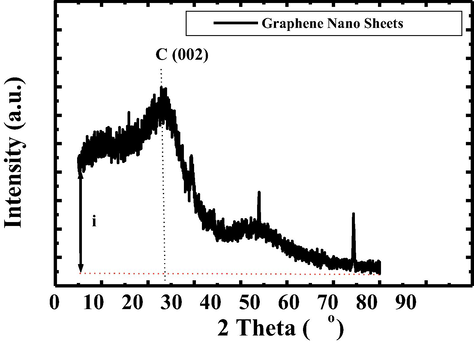

The XRD data of Graphene Nano Sheets Switching is shown in Fig. 1.

XRD pattern of graphene nano sheets switching.

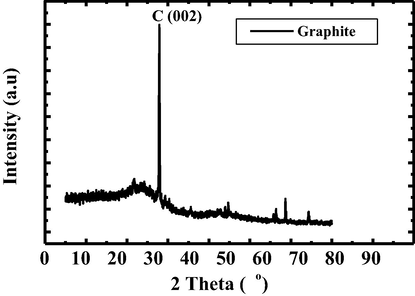

The intensity of Graphene Nano Sheets Switching is much more far from zero number. That is due to the shadow effect and material will be switching. In the case of Graphene Nano Sheets Switching, the position of coconut was far distance from its shadow during the heating process on coconut until the coconut is cracked. On the other hand, the formation of graphite Fig. 2) occures due to coconut position is embedded on its shadow during the cracking process by assist of heat of oven.

XRD pattern of graphite.

Figs. 1 and 2 explain that soul atom relates to its shadow. That is explained by our hypoythesis about soul atom Fig. 3).

Hypothesis of soul atom.

Fig. 3 shows that atom has shadow. While shadow embedded on atom will result the sharp peak, indicating C-crystalin. But, while atom and shadow is far away each other, it will result C-amorphous. This phenomenon, we call soul atom. We may express this phenomenon by gradually step.

3.1 Aluminum (Al)-vessel effect

Step-1: First, coconut shell was put on Al-vessel for cracking process. We suppose that Al as a base Lewis will donate its electron into coconut shell during the cracking process. It may affect the coconut shell will be cracking due to entropy effect. Finally, it was continue with pyrolized on 600 °C. During, pyrolisation process, the high temperature will contribute to supply many electrons into carbon of coconut shell. It supposes to generate the large and narrow of carbon atoms and graphite is formed.

3.2 Glass-vessel effect

Step-1: First, coconut shell was put on glass-vessel for cracking process. Glass as an inert material will relatively slow to donate electron into coconut shell during the cracking process. It may affect the coconut shell will be cracking due to entropy effect for a much more time than Al-vessel. Finally, it was continue with pyrolized on 600 °C. During, pyrolisation process, the high temperature will contribute to supply not so many electrons into carbon of coconut shell. It supposes to generate the small and broad of carbon atoms and graphene nano sheets is formed.

4 Conclusion

Each of atom has soul (shadow). The shadow phenomenon relates to the C-physical properties. We also succeed to produce graphite from coconut by using versatile method and large scale product. The vessel for cracking process may affect the kind and properties of carbon.

References

- Nature. 2012;490:192-200.

- Nano Lett.. 2008;8:1704-1708.

- Nat. Nanotechnol.. 2008;3:563-568.

- Phys. Rev. B. 1998;58:16396-16406.

- J. Phys. Chem. B. 2004;108:19912-19916.

- Science. 2006;313:951-954.

- Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A.. 2005;102:10451-10453.

- Science. 2011;331:568-571.

- Science. 2009;324:1312-1314.

- Nat. Nanotechnol.. 2010;5:574-578.

- Science. 2009;323:610-613.

- Small. 2010;6:2877-2884.

- ACS Nano. 2011;5:1253-1258.

- J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 2009;21:344205.

- ACS Nano. 2011;30 A-K

- ACS Nano. 2011;5:1785-1791.

- Nat. Nanotechnol.. 2009;4:25-29.

- Siburian, R., Kondo, T., Nakamura, J., J. Phys. Chem. C 117 (7), 3635–3645.

- Siburian, R., Nakamura, J., J. Phys. Chem. C 116 (43), 22947–22953.

- Siburian, R., Int. Res. J. Pure Appl. Chem. 4(5), 541.

- Siburian, R., Sebayang, K., Supeno, M., Marpaung, H., Chem. Select 2(3), 1188–1195.

- Siburian, R., Sebayang, K., Supeno, M., Marpaung, H., Oriental J. Chem. 33(1), 134–140.