Translate this page into:

Natural enemies feeding on some Centaurea species in the Yüksekova basin

⁎Corresponding author at: Siirt University, Kurtalan Vocational School, Plant and Animal Production Department, Siirt, Turkey. mesutsirri_30@hotmail.com (Mesut Sırrı)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Background

Excessive and unconscious use of pesticides in agricultural areas negatively affects ecosystem services and biodiversity and threatens human and environmental health. Therefore, natural enemies (biological control agents) that could be utilized to suppress the infestation of diseases, pests and weeds have attracted the attention of scientists globally. There are limited studies on the occurrence of natural enemies on Centaurea species in the Yüksekova basin, Turkey. The Yuksekova basin has a rich floristic diversity; however, remained unexplored and underutilized. Limited use of pesticides, and the presence of natural enemies feeding on weeds in the region have recently attracted the attention of researchers for searching biological control agents. Asteraceae is the dominant family in the region with the highest diversity, causing significant yield losses in agricultural area of the basin.

Methods

Therefore, preliminary studies were conducted to determine the natural enemies feeding on the genus Centaurea. The region was divided into 10 × 10 cm systematic grids and occurrence of Centaurea species, and their natural enemies were recorded.

Results

The survey identified 10 species belonging to Centaurea genus in the study area. Different insect species, i.e., Lixus pulverulentus Scopoli, Larinus grisescens Gyllenhal and Bangasternus orientalis Capiomont belonging to Curculionidae (Coleoptera) family were observed to feed and spend biological periods on Centaurea behen L., Centaurea pterocaula Trautv. and Centaurea iberica Trev. ex Spreng species.

Conclusions

It is estimated that the natural enemies recorded on Centaurea species could be potentially used in biological control of the species on which they were recorded in the current study. However, detailed studies on host specificity and efficacy of the identified insect species are needed.

Keywords

Centaurea species

Natural enemies

Biological control

Survey

Yüksekova basin

Turkey

1 Introduction

Several biotic and abiotic factors such as humans, animals, and plant protection factors in addition climate and soil significantly alter crop production. Rapid climate changes have made weed infestations more important, as uncontrolled large weed populations cause serious yield and economic losses (Önen and Özcan, 2010). Weeds cause massive economic losses in agricultural areas, since they compete with cultivated plants for light, water, nutrients and space, host harmful microorganisms and disrupt agricultural activities (Özer et al., 2001). Yield losses due to weeds vary depending on crop species and prevailing ecological conditions, and may reach ∼90% (Önen et al., 1997). For this reason, it is estimated that weeds cause ∼150 billion dollars’ losses annually in agricultural production at global level (Döken et al., 2000).

Weed management has been initiates with the beginning of agriculture and continues till today. Hand pulling, and crop rotation were the primitive methods of weed control at the start of agriculture. However, mechanical and physical management methods were started with industrial development and mechanization. In the later period, especially after World War II, weed management witnessed a golden period since most of the herbicides were developed and utilized for weed management in this era. Unfortunately, herbicides have resulted in the evolution of resistance in numerous weed species and posed serious negative impacts on environment and human health. For this reason, farmers have started to avoid chemical control and directed towards biological control. Biological control is harmless to natural and biological diversity and could serve as alternative to herbicides (Delen and Tosun, 1997).

Excessive and unconscious use of herbicides in the recent years had imposed severe negative impacts on human health, food safety and ecosystem. Therefore, biological control of weeds has emerged as one of the best alternative methods to chemical control (Uygun et al., 2010). Biological control is based on the deliberate use of target-specific natural enemies to control weeds. The use of biological control has increased rapidly around the world, especially in meadow-pastures and agricultural areas. Biological control is one of the most effective methods in the control of invasive species that cause significant ecological and economic problems. Biological control is the reinforcement, protection, and support of natural enemies that directly or indirectly damage or weaken the host weed species, without harming the cultivated plants (DeBach, 1964; Atay et al., 2015).

More than 200 weed species are controlled by ∼500 natural enemies in >90 countries, including the USA, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa, which are top users in exploiting natural enemies for weed management globally (Day and Witt, 2019). Biological control agents generally consist of insects, microbial agents (fungi, bacteria, and viruses) and polyphagous organisms (mammals, fish, geese, snails, etc.) (Uygun et al., 2010; Atay et al., 2015).

Biological control studies against weeds in Turkey have generally been limited to the detection of natural enemies. The first studies on biological control of Centaurea species in the country were conducted Cristofaro et al (2002). Field studies were carried out to detect harmful insect species feeding on Centaurea solstitialis L. and quantify their damages. Afterwards, studies were conducted to determine population densities for biological control of C. solstitialis in the Eastern Mediterranean region (Uygur et al., 2004; Uygur et al., 2012).

The Asteraceae family is one of the richest families in the world in terms of species’ diversity. Most of the Asteraceae species are cosmopolitan (Attard and Cuschieri, 2009). Similarly, the Asteraceae is one of the families with the highest number of flowering plant species in the local flora in Turkey, especially in agricultural areas (Güner et al., 2012). More importantly, Turkey is one of the main centers of Centaurea species’ diversity (Wagenitz, 1986). Globally, there are >700 plant species belonging to the genus Centaurea (Bensouici et al., 2012) and 205 of them are in the flora of Turkey (Şirin et al., 2020). Of the 700 species, 125 are endemic (Güner et al., 2012; Uysal 2012; Bancheva et al. 2014; Uysal et al. 2015). The local flora of Hakkari province includes 26 Centaurea species, of which 5 are endemic (Güner et al., 2012).

The aim of this study was to pre-screen the Curcullonidae species feeding on the leaves, stems, and seeds of C. behen, C. pterocaula and C. iberica, which have established populations in the Hakkari region.

2 Materials and methods

The study was carried out in Gever plain situated at altitude of 1950 in Hakkari/Yüksekova district of Eastern Anatolia Region, Turkey during 2020. The study area is located between 37.427253° N – 37.598928° N latitudes and 44.071683° E – 44.423028° E longitudes.

The study region is rich in biodiversity, and ecological balance and limited use of pesticides increases the chances of occurrence of biological control agents. Centaurea belonging to the Asteraceae family causes important problems, especially in agricultural areas in Turkey and the world. Therefore, pre-screening of the diversity, density and natural enemies feeding on different species of the genus was conducted in this study.

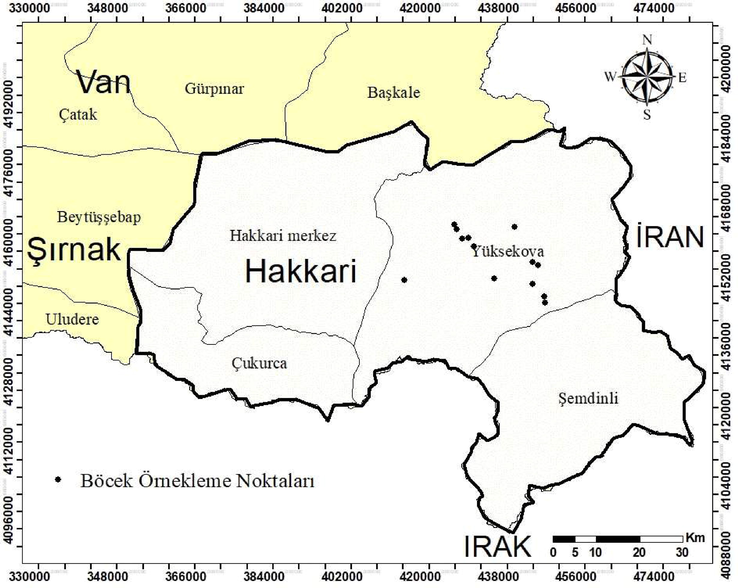

Centaurea species were observed in agricultural areas, meadow-pastures and roadsides to find out the biological control agents feeding on them. In the study, observations were made at 20 points separated by 1 km distance (including intermediate transect points) based on the main and intermediate roads in the region. In addition, Centaurea species were examined in an area of 20 × 20 square meters at each sampling point. Adults and larvae feeding on plants were collected, cultured, and identified in the laboratory. The locations of the natural enemies detected on Centaurea species are given in Fig. 1.

Locations of natural enemies feeding on Centaurea species in Yüksekova Basin.

3 Results and discussion

In the survey, 10 species belonging to the Centaurea genus were identified. The scientific name, Turkish name, phytogeographic region, origin, density, and frequency of occurrence of these plants are given in Table 1. The C. iberica (47.91%), C. pterocaula (33.73%) and C. behen (12.54%) were the most common dense species in the surveyed region. However, the most abundant and densely distributed species in agricultural areas in the region were C. iberica and C. pterocaula.

Latin name

Turkish name

Phytogeographic region

Origin

Density (plant m−2)

Frequency of occurrence (%)

Asteraceae

Centaurea behen L.

Zerdalidikeni

Iran-Turan elements

1,01

12,54

Centaurea carduiformis DC. subsp. carduiformis var. carduiformis

Kavgalaz

0,67

1,27

Centaurea gigantea subsp. Gigantea

Daldakdikeni

1,50

0,90

Centaurea glastifolia L.

Kotankıran

Iran-Turan elements

1,00

0,69

Centaurea iberica Trev. ex Spreng.

Deligözdikeni

Africa, Europe, Asia

1,60

47,91

Centaurea nemecii Nábĕlek

Delikavgalaz

Iran-Turan elements

0,95

5,93

Centaurea persica Boiss.

Acemkavgalazı

Iran-Turan elements

1,00

0,95

Centaurea pterocaula Trautv.

Çoruşbozan

Iran-Turan elements

1,17

33,73

Centaurea solstitialis subsp. solstitialis L.

Çakırdikeni

Iran-Turan elements

Cosmopolit

1,00

0,95

Centaurea virgata Lam.

Acısüpürge

Iran-Turan elements

Africa, Europe, Asia

1,00

1,64

The insect species directly feeding on the host species and causing damage were recorded in surveys. For this purpose, areas with frequent distribution of Centaurea species were surveyed in different periods. In the study, 3 insect species belonging to Curculionidae family were found feeding on Centaurea species, caused visible damage and spent their biological stages. The information on the detected host weed species and insects feeding on them are summarized below.

3.1 Host species: Centaurea behen L.

The C. behen is naturally distributed between altitudes of 340–1950 m. Generally, the speices is distributed in agricultural areas, fallow lands, meadow-pasture, rocky slopes, barren lands, and roadsides in the surveyed region (Davis, 1975; Özaslan, 2011; Ateş, 2019).

3.2 Morphological characteristics

The C. behen is perennial with erect glabrous stems. Its height can vary between 60 and 150 cm, and branches exceed the main axis with several capitulas from above. The leaves are hard and veins are fluffy and hairless. Although the leaf shapes vary according to the location, they can be generally lanceolate, oblong, broad-lanceolate or ovate-lanceolate. The length of the lower leaves is 10–13 cm, width is 6–10 cm, length of the middle leaves is 5–6 cm, and width is 1.5–2.5 cm. The flowering period is usually in June-August, and the flowers are yellow, with achenes exceeding 5 mm and pappus 5–8 mm (Ateş, 2019; Anonymous, 2021c).

3.3 Natural enemies: Lixus pulverulentus Scopoli (Coleoptera: Curculionidae)

Distribution in the world: Western Palaearctic and central Asia (Dieckmann, 1983). Alonso-Zarazaga (2008) clearly shows the synonymy: Lixus pulverulentus [= L. angustatus (Fabricius, 1775)]. Albania, Austria, Bulgaria, Cyprus, France, Georgia, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Moldova, Netherlands, Romania, Slovakia, Syria, Turkey, Ukraine (Anonymous, 2021b).

Distribution in Turkey: Hatay-Antakya [Lodos et al. (2003) referred to it as sub-L. algirus (Linnaeus, 1758)] and Osmaniye (Pehlivan et al., 2005).

Material examined: Yüksekova basin Latitude-Longitude: 429149D-4159086K, 427603D-4158940K, 425838D-4162250K, 439750D-4161692K, 445231D-4152902K, 414378D-4149438K, 434989D-4149786K altitude, 1866–1950 m.

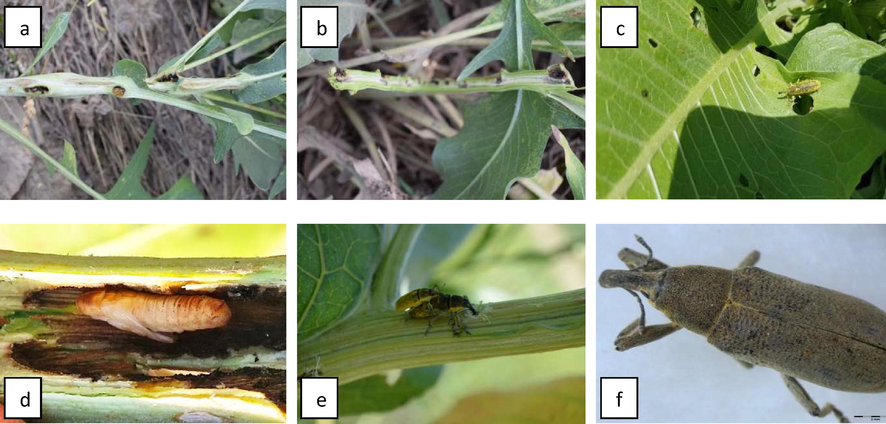

Recorded hosts: Malvaceae, Asteraceae, and Fabaceae (Alcea rosea, Malva pusilla, Malva sylvestris. Malva thuringiaca. Cirsium arvense, Cirsium palustre, Cirsium serrulatum, Carduus acanthoides, Silybum marianum, Centaurea nigra, Onopordum acanthium, Vicia faba (Dieckmann, 1983; Boukhris-Bouhachem et al., 2016; Arzanov, 2017; Anonymous, 2021b) (Fig. 2).

Centaurea behen (a,b,c) infested with the larvae of Lixus pulverulentus (d,e,f).

New host record: In the present study, Centaurea behen was recorded as a new host of Lixus pulverulentus from Hakkari/Turkey for he first time in the world (Fig. 2).

3.4 Larinus grisescens Gyllenhal (Coleoptera: Curculionidae)

Distribution in the world: Bullgaria, Central Asia, Greece, Israel, Italy, Kazakhstan, Montenegro, North Africa, North Macedonia, Russia, Serbia, Southern Europe, Syria, Transcaucasia and Turkey.

Distribution in Turkey: Adana, Adıyaman, Artvin, Bingöl, Bitlis, Diyarbakır, Elazığ, Erzurum, Erzincan, Gaziantep, Hatay, Iğdır, Kars, Kırıkkale, Kilis, Malatya, Nevşehir, Osmaniye, Sivas and Şanlıurfa (Özgen et al., 2016; Gültekin, 2006) (Fig. 3).Fig. 4..

Centaurea behen (a) infested with the larvae of Larinus grisescens (b,c).

Centaurea ptercaula (a) infested with the larvae of Larinus grisescens (b,c).

Material examined: Yüksekova basin Latitude-Longitude: 445231D-4152902K, 429149D-4159086K, 429149D-4159086K, 425838D-4162250K, altitude, 1866–1950m.

Recorded hosts: Carthamus tinctorius L. (Asteraceae), Astragalus cephalanthus Dc. (Fabaceae) (Abad et al., 2016), Carthamus oxyacantha M. Bieb. (Asteraceae) (Shahriyari-Nejad et al., 2013), Carduus spp. (Asteraceae) (Özgen et al., 2016) (Fig. 3).

New host record: In the present study, Centaurea behen was recorded as a new host of Larinus grisescens from Hakkari/Turkey for he first time in the world (Fig. 3).

Host species: Centaurea pterocaula Trautv. (Asteraceae).

The C. ptercaula generally spreads in agricultural areas, meadows, dry slopes, empty lands, and roadsides in the region. Its natural distribution areas are between 900 and 2400 m (Tugay et al., 2006).

3.5 Morphological characteristics

The C. ptercaula is a perennial with an erect stem, branches towards the top and can reach to 2 m in height. The leaves generally change according to their location, the base and lower leaves are petiolate, 4–5 cm, the middle and upper leaves are sessile. The leaf form gradually narrows towards the upper part. The flowering period is between July and August, and the color of the flowers is yellow, achenes 6 mm, pappus 6–11 mm (Davis et al., 1988; Tugay et al., 2006).

Material examined: Yüksekova basin Latitude-Longitude: 443906D-4148512K, 443844D-4153660K, 429149D-4159086K altitude, 1866–1950m.

Natural enemies: Larinus grisescens Gyllenhal (Coleoptera: Curculionidae).

Host species: Centaurea iberica Trev. ex Spreng. (Asteraceae).

It has been stated that the general distribution of C. iberica is in natural areas, agricultural areas, water and roadsides, waste areas and pasture areas (Tadmor et al., 1974; Wagenitz, 1975; Keil and Ochsmann, 2006; DiTomaso and Healy, 2007). However, Nasir and Sultan (2006) reported that C. iberica is one of the three most important weeds in the mustard fields in the Chakwal Region of Pakistan. It ranks seventh in the general weed ranking in the region. In the studies carried out in the region, it has been determined that the plant is found in similar areas and is one of the most common weeds.

3.6 Morphological characteristics

Although C. iberica has a widespread distribution (about 2300 m), germination, rosette formation and flowering periods vary depending on ecological factors. It usually blooms in May-July and the flower color is seen as pale pink (Whitson et al., 1996). The plant can be an annual, biennial, or short-lived perennial (Keil and Ochsmann, 2006). It usually grows in a forum that can grow up to 68–96 cm in length and starts at the bottom and branches repeatedly. Its leaves are sparsely hairy, and their leaf length varies between 2 and 11 cm and width 2–4 cm (DiTomaso and Healy, 2007; Türkoğlu et al., 2009; Ateş, 2019).

3.7 Natural enemies: Bangasternus orientalis Capiomont (Coleoptera: Curculionidae)

Distribution in the world: Afghanistan, Armenia, Austria, Azerbaijan, Bulgaria, Central European Territory, Cyprus, Egypt, Georgia, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Jordan, Kazakhstan, North Macedonia, Romania, Russia, Slovakia, Southern Europe, Tajikistan and Turkey (Capiomont, 1873; Sert, 1995).

Distribution in Turkey: Adana, Ankara, Antalya, Aydın, Batman, Bilecik, Bitlis, Cankiri, Diyarbakir, Elazig, Eskisehir, Gaziantep, Hatay, Icel, Izmir, Kahramanmaras, Karabuk, Karaman, Kayseri, Kilis, Konya, Kırşehir, Manisa, Mardin, Mugla, Niğde, Osmaniye, Sivas, Trabzon, Yozgat (Lodos et al., 1978, 2003; Sert, 1995; Pehlivan et al., 2005; Erbey, 2010; Yılmaz, 2015). In the present study, Bangasternus orientalis was recorded as a new record for Hakkari Province insect fauna from Turkey (Fig. 3).

Material examined: Yüksekova basin Latitude-Longitude: 446663D-4145693K, 446709D-4144147K, 430363D-4157125K altitude, 1866–1950 m.

Recorded hosts: Centaurea solstitialis L. (Yellow starthistle) (Asteraceae) Centaurea virgata Lam. (Squarrose knapweed) (Asteraceae), Centaurea iberica Trev ex Sprengel (Iberian starthistle) (Asteraceae), Centaurea calcitrapa L. (Purple starthistle) (Asteraceae) (Ter-Minassian, 1978; Maddox et al., 1991; Gültekin, 2008; Anonymous, 2021a).

Host record: In the present study, Centaurea iberica was recorded as a host of Bangasternus orientalis from Hakkari/Turkey (Fig. 5).

Centaurea iberica Trev. ex Spreng. (a, b), Bangasternus orientalis (Capiomont, 1873) (c).

Although the flora of Turkey is rich in Centaurea species, biological control studies are limited in the control of these species. In addition, any research conducted in Turkey on the biological control of C. behen, C. iberica and C. ptercaula species detected in the region has not been found in the literature. For this reason, determining biological control possibilities of these weed species has attracted the attention of researchers. In the study, although C. iberica was the most common species in the region, Bangasternus orientalis (Capiomont, 1873) was observed at only 3 locations feeding on the species. Similarly, C. ptercaula was one of the most widespread species in the region, Larinus grisescens feeding was observed in 3 locations. These two species spread in agricultural and grassland areas, it is suspected that the distribution and population density of insects may have been suppressed due to the mowing of weeds in these areas. Although the population density of C. behen was low in the region than the other two species, the densities of Lixus pulverulentus and Larinus grisescens species feeding on the plant and the number of feeding locations were higher.

4 Conclusion

Yüksekova Basin is an important phytogeographic region in terms of endemism due to its geographical location, topographic structure, and ecological factors. The region is in the “Iran-Turan Element”, which further enriched its biological diversity. In addition, limited agricultural activities in the region and, more importantly, the almost non-existent use of chemical inputs has completely transformed the region into a natural ecosystem. For this reason, the investigation of weeds and natural enemies in the region suggests that it can help in the biological control of weeds that cause problems in agricultural areas and invasive weeds that become more widespread with global warming.

Acknowledgement

The current study was produced from the first author's doctoral thesis. This study was supported by Scientific Research Projects Commission (DÜBAP) of Dicle University, Diyarbakır under grant number DUBAP.21.002. This project was supported by Researchers Supporting Project number (RSP-2023R7) King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Faunistic contributions of the subfamily Lixinae Schoenherr (Coleoptera, Curculionidae) from Iranian rangelands. Journal of Insect Biodiversity and Systematics. 2016;1(2):147-154.

- [Google Scholar]

- The types of Palaearctic species of the families Apionidae, Rhynchitidae, Attelabidae and Curculionidae in the collection of Étienne Louis Geoffroy (Coleoptera, Curculionoidea) Graellsia. 2008;64(1):17-44.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous, 2021a. http://mtwow.org/Bangasternus-orientalis.html. Date: 08.06.2021.

- Anonymous, 2021b. https://ukrbin.com/show_image.php?imageid=132240. Date: 08.06.2021.

- Anonim, 2021c. Türkiye Bitkileri. com, https://turkiyebitkileri.com/tr/foto%C4%9Fraf-galerisi/asteraceae-papatyagiller/centaurea-peygambercice%C4%9Fi/centaurea-behen.html. (Erişim: 31.12.2021).

- Arzanov, Y.G., 2017. Description of the preimaginal stages and biology of the weevil Lixus (Dilixellus) pulverulentus (Scopoli, 1763) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Lixini), 2017. Caucasian Entomological Bulletin , Vol.13 No.1 pp.53-58 ref.12.

- İstilacı yabancı otlarla biyolojik mücadele. Türkiye istilacı bitkiler katalogu, Editör Huseyin Onen, s: 81–118. Tarımsal Araştırmalar ve Politikalar Genel Müdürlüğü, Bitki Sağlığı Araştırmaları Daire Başkanlığı. Ankara. ISBN: 978-605-9175-05-0; 2015.

- Adıyaman Bölgesinde Yetişen Centaurea, Cyanus, Psephellus Cinslerine Ait Türler Üzerinde Morfolojik ve Palinolojik Araştırmalar (Yüksek lisans Tezi) Bartın Üniversitesi Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü Orman Mühendisliği Anabilim Dalı. 2019;s. 98

- [Google Scholar]

- In vitro immunomodulatory activity of various extracts of Maltese plants from the Asteraceae family. Journal of Medicinal Plants Research. 2009;3:457-461.

- [Google Scholar]

- Centaurea aytugiana (Asteraceae), a new species from North Anatolia, Turkey. Novon. 2014;23(2):133-138.

- [Google Scholar]

- Centaurea foucauldiana'dan seskiterpen laktonlar ve flavonoidler. Chem Nat Compd. 2012;48:510-511.

- [Google Scholar]

- First Report on Natural Enemies of Lixus pulverulentus on Faba Bean Crops in Tunisia. Tunisian Journal of Plant Protection.. 2016;Vol. 11, No. 2

- [Google Scholar]

- Capiomont, G., 1873. Monographie des Rhinocyllides. Mise en ordre d’après les manuscrits de l’auteur par M. C.- E. Leprieur. Annales de la Société Entomologique de France (5) 3 (3): 273-279. [24-XII-1873].

- Cristofaro, M., Hayat, R., Gültekin, L., Tozlu, G., Zengin, H., Tronci, C., Lecce, F, Şahin, F. and L. Smith, 2002. Preliminary secreening of natural enemies of Yellow starthistle, Centaurea solstitialis L (Asteraceae) in Eastern Anatolia. Türkiye 5. Biyolojik Mücadele Kongresi Bildirileri, 4-7 Eylül, Erzurum s: 287-295.

- Centaurea L. Flora of Turkey and the East Aegean Islands(suppl.). Vol vol 10:166–169. Edinburgh: Edinburgh univ. Ss; 1988.

- Edinburgh Univ. Press. 1975;5:465-585.

- Weed Biological Control: Challenges and Opportunities. Weeds – Journal of Asian-Pacific Weed Science Society. 2019;1(2):34-44.

- [Google Scholar]

- Debach P. (1964) Successes, Trends and Future Possibilities. In Biological Control of Insect Pests and Weeds (Eds. P. DeBach and E.I. Schlinger), 673-713.

- Türkiye’de Pestisit Kullanımının Toksikolojik Değerlendirilmesi. Ankara: II. Ulusal Toksikoloji Kongresi; 1997. p. :314-317.

- Dieckmann, L., 1983. Beiträge zur Insektenfauna der DDR: Coleoptera-Curculionidae (T anymecinae, Leptopiinae, Cleoninae, Tanyrhynchinae, Cossoninae, Raymondionyminae, Bagoinae, T anysphyrinae). Mit 164 T extfiguren. Beiträge zur Entomologie, 33(2): 257-381.

- DiTomaso, JM., Healy, EA., 2007. Weeds of California and other Western States. Vol 1. California, USA: UC Davis, 1808 pp. [University of California ANR Pub. 3488.].

- Fitopatoloji, Atatürk Üniversitesi Yayınları No:729, Ziraat Fakültesi Yayınları No:314, Ders Kitapları Serisi No:66. Erzurum, s 2000:121-122.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bolkar dağlarının Curculionidae (Coleoptera) familyası üzerinde taksonomik ve morfolojik çalışmalar. Doktora tezi, Gazi Üniversitesi. Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü 2010 486 s, Ankara

- [Google Scholar]

- Fabrıcıus, J.C. 1775. Systema entomologiae, sistens insectorum classes, ordines, genera, species, adjectis synonymis, locis, descriptionibus, observationibus. Korte, Flensburgi et Lipsiae, XXX + 832 pp.

- Gültekin L., 2006. Seasonal occurrence and biology of globe thistle capitulum weevil Larinus onopordi (F.) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) in northeastern Turkey. Munis Entomology & Zoology, 2006; 1(2):191-198.

- Host plants of Larinus latus (Herbst 1784) in eastern Turkey. - Weevil News. 2008;40:9.

- Türkiye Bitkileri Listesi (Damarlı Bitkiler). İstanbul: Nezahat Gökyiğit Botanik Bahçesi ve Flora Araştırmaları Derneği Yayını; 2012.

- Centaurea. In: Oxford U.K., ed. Flora of North America north of Mexico. Vol Vol. 19. Oxford University Press; 2006. p. :181-194.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lınnaeus, C. von. 1758. Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Editio decima, reformata. Tom I. Salvius, Holmiae, 823 [+1] pp.

- Ege ve Marmara Bölgelerinin Zararlı Böcek Faunasının Tesbiti Üzerinde Çalışmalar [(Curculionidae, Scarabaeidae (Coleoptera); Pentatomidae, Lygaeidae, Miridae (Heteroptera)]. T. C. Gıda, Tarım ve Hayvancılık Bakanlığı. Ankara: Zir. Müc. Zir. Kar. Gen. Md. Yay; 1978. p. :301.

- Faunistic Studies on Curculionidae (Coleoptera) of Western Black Sea. Meta Basım Matbaacılık Hizmetleri, Bornova, İzmir: Central Anatolia and Mediterranean Regions of Turkey; 2003. p. :83.

- Impact of Bangasternus orientalis (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) on achene production of Centaurea solstitialis (Asterales: Asteraceae) at a low and high elevation site in California. Environ. Entomol.. 1991;20:335-337.

- [Google Scholar]

- Noxious weeds of winter crops in District Chakwal, Pakistan. International Journal of Agricultural Research. 2006;1(5):480-487.

- [Google Scholar]

- Önen, H., Özer, Z., Tursun N., 1997. Kazova (Tokat)'da Yetiştirilen Şekerpancarı (Beta vulgaris L.) Verimine Yabancı Otların Etkileri Üzerinde Araştırmalar. II. Türkiye Herboloji Kongresi, 1-4 Eylül 1997. İZMİR- AYVALIK.

- Önen, H. ve Özcan, S. (2010). İklim Değişikliğine Bağlı Olarak Yabancı Ot Mücadelesi. In: SERİN Y Eds. Küresel İklim Değişimine Bağlı Sürdürülebilir Tarım, Cilt II YİBO Eğitimi., Erciyes Üniversitesi Yayın No:177, Erciyes Üniversitesi Seyrani Ziraat Fakültesi Yayın No:1, Fidan Ofset, Kayseri, pp 336-357.

- Diyarbakır İli buğday ve pamuk ekim alanlarında sorun olan yabancı otlar ile üzerindeki fungal etmenlerin tespiti ve bio-etkinlik potansiyellerinin araştırılması. Selçuk Üniversitesi, Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü, Konya: Doktora Tezi; 2011.

- Herboloji (Yabancı Ot Bilimi) Gaziosmanpaşa Üniversitesi, Ziraat Fakültesi Yayınları. 2001;No:20:412. sayfa

- [Google Scholar]

- New Faunistic Records of Weevils Curculionoidea (Coleoptera) Elazığ Province (Turkey) Journal of Entomology and Zoology Studies. 2016;4(5):846-850.

- [Google Scholar]

- Contributions to the knowledge of the Lixinae (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) from Turkey. Türkiye entomoloji dergisi. 2005;29(4):259-272.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sert, O., 1995. Iç Anadolu Bölgesi Curculionidae (Coleoptera) Famliyası Üzerinde Taksonomik Çalısmalar Hacettepe Üniversitesi Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü, Doktora Tezi, Ankara.1-184 s.

- Identification of Species Lixini Tribe From South of Kerman Region. Iran (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Lixinae: Lixni). Mun. Ent. Zool.. 2013;8(1) January 2013

- [Google Scholar]

- ‘Centaurea akcadaghensis’ and ‘C. ermenekensis’ (Asteracaeae), two new species from Turkey. Mediterranean Botany. 2020;41(2):173-179.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Plant and sheep production on semiarid annual grassland in Israel. Journal of Range Management. 1974;27(6):427-432.

- [Google Scholar]

- Weevils of the subfamily Cleoninae in the fauna of the USSR. Co: Tribe Lixini, New Delhi, Amarind Publ; 1978.

- İki Centaurea L. (Compositae; Sect.; Chartolepis (Cass) DC.) Taksonu Üzerine Morfolojik ve Karyolojik Bir Araştırma. Selçuk Üniversitesi, Fen Bilimleri Dergisi. 2006;28:59-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of temperature on germination biology in Centaurea species. African Journal of Agricultural Research. 2009;4(3):259-261.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biyolojik Mücadele, Türkiye Biyolojik Mücadele Dergisi, 1(1), 1–14. ISSN 2010:2146-10035.

- [Google Scholar]

- Population densities of yellow starthistle (Centaurea solstitialis) in Turkey. Weed Science. 2004;52:746-753.

- [Google Scholar]

- The effects of seed feeding insects on seed production of yellow starthistle (Centaurea solstitialis L.) in Adana province in southern Turkey. Türkiye Biyolojik Mücadele Dergisi. 2012;3(2):99-120.

- [Google Scholar]

- Uysal, T., 2012. Centaurea L. In: Güner, A., Aslan, S., Ekim, T., Vural, M. & Babaç, M.T. (Eds.) Türkiye Bitkileri Listesi (Damarlı Bitkiler). Nezahat Gökyiğit Botanik Bahçesi ve Flora Araştırmaları Derneği Yayını, İstanbul, pp. 127–140.

- Uysal, T., Dural, H., Tugay, O., 2015. Centaurea sakariyaensis (Asteraceae), a new species from Turkey. Plant Biosystems. [Published online].

- Wagenitz, G., 1975. Centaurea L. In: Flora of Turkey and the East Aegean Islands, ed: P.H. Davis, Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh, Vol.5, pp.536.

- Proc R Soc Ed. 1986;89:11-21.

- Whitson, T.D., Burrill, L.C., Dewey, S.A., Cudney, D.W., Nelson, B.E., Lee, R.D., Parker, R., 1996. Weeds of the west. Laramie, Wyoming, USA: Western Society of Weed Science in cooperation with Cooperative Extension Services, University of Wyoming, 630 pp.

- Curculionidae (Coleoptera) familyası üzerinde taksonomik ve morfolojik araştırmalar. Ahi Evran Üniversitesi / Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü / Biyoloji Anabilim Dalı Kırşehir. Doktora Tezi. 2015

- [Google Scholar]