Translate this page into:

Mycotoxigenicity of Fusarium isolated from banana fruits: Combining phytopathological assays with toxin concentrations

⁎Corresponding author. malghuthaymi@su.edu.sa (Mousa Alghuthaymi),

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Seven species of Fusarium isolated from rotten bananas were studied for their mycotoxigenicity. The first pathogenicity assay revealed symptoms of Fusarium rot infection when the Fusarium isolates were inoculated to wounded banana fruits. The second pathogenicity assay, where seedlings of Nicotiana were inoculated with Fusarium isolate filtrations, revealed evidence for the pathogenicity for six of the Fusarium species. One species, Fusarium oxysporum did not display any pathogenicity symptoms on Nicotiana seedlings. It neither produced the mycotoxins fumonisin, zearalenone and deoxynivalenol, which were produced by all of the other species. However, the mycotoxin concentrations did not correlate with the disease severity in the pathogenicity assay with banana fruits. We conclude that that pathogenicity is a complex issue regulated by many factors and several toxins and the pathogenicity assessment needs bioassays with a multi-mycotoxin approach.

Keywords

Virulence

Toxicity

Crown rot

Mycotoxin

1 Introduction

Banana (Musa spp.) is the most commonly cultivated and exported fruit throughout the world and a significant source of income for many developing countries. Banana fruits are often spoiled by fungal infections (Fu et al., 2017; Kamel et al., 2016; Lassois et al., 2010). One common genus, Fusarium causes appreciable yield losses in many perennial crops, including bananas (Deltour et al., 2017; Mirete et al., 2004). Serious diseases of banana are Fusarium fruit rot and Fusarium crown rot (Hirata et al., 2001; Kamel et al., 2016; Moretti et al., 2004).

Mycotoxins produced by filamentous fungi have been extensively studied, as recently reviewed by (Alshannaq and Yu, 2017). Furthermore, our knowledge about Fusarium mycotoxins (e.g., deoxynivalenol, fumonisins, moniliformin, and zearalenone) has increased(Asam et al., 2017; Chakrabarti and Ghosal, 1986; Hirata et al., 2001; Jimenez et al., 1997; Vesonder et al., 1995; Zakaria et al., 2012) The pathogenicity and toxicity of different compounds vary considerably and may depend upon the origin of the fungus. Deoxynivalenol is among the most common and well-studied mycotoxins, but it has been assessed to have relatively low toxicity (Bennett and Klich, 2003). Most studies have focused on studying the toxicity of the chemical compounds separately. However, fungi produce several toxins at the same time (Botha et al., 2018). Due to a wide variety of toxins, fungi and hosts, additional knowledge based on a multi-mycotoxin approach is needed. The actual toxicity is not straightforward to assess and, therefore, the development of bioassays for assessing the toxicity of the particular fungal infection are needed.

Our objective was to assess the mycotoxigenicity and virulence of different species of Fusarium isolated from stored banana fruits. We carried out two pathogenicity assays, one with banana fruits and another with Nicotiana seedlings. We hypothesized that the mycotoxin concentrations and toxicity symptoms correlate positively. To verify the hypothesis, we analyzed the relationship that existed between the severity of the disease the different Fusarium species caused and the concentrations of toxins they produced. The study will provide understanding how the toxins affect the virulence.

2 Materials and methods

Banana fruits (50) with typical symptoms of fruit rot disease were randomly collected from markets at five locations in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The bananas originated randomly from Brazil, Costa Rica, Ecuador, and Malaysia.

Ten samples (each consisting of a piece approximately 0.5 cm × 0.5 cm) of banana fruits that displayed rot symptoms were disinfected with a 4% sodium hypochlorite solution, plated onto potato dextrose agar (PDA, HiMedia chemicals, Mumbai, India), and a single spore culture was prepared and stored as described previously by Alghuthaymi and Bahkali (2015). Identification of the fungi, according to morphological and molecular techniques, is provided by Alghuthaymi and Bahkali (2015). The seven species used in the experiments were F. semitectum (5 isolates), F. proliferatum (3 isolates), F. circinatum (3 isolates), F. chlamydosporum (3 isolates), F. solani (2 isolates), F. oxysporum (2 isolates), and F. thapsinum (1 isolate).

A pathogenicity assay was then carried out to study the virulence of the various species of Fusarium on banana fruits. Healthy banana fruits were surface sterilized with ethanol (70%) for 2 min, washed with sterile distilled water for 2 min, and placed on filter paper for drying. Four replicate PDA plates for each of the fungal isolates were prepared and incubated at 25 °C for seven d. Fungal conidia were collected using 20 mL sterile distilled water. Bananas were wounded with a sterile knife and a conidial solution (300 µL) was inoculated into the inner tissue of the banana using sterile tips. One banana was inoculated for each PDA plate. Bananas were incubated for seven d. The assay was carried out with four replicates and repeated twice. Four non-inoculated bananas were used as controls. The disease severity index (DSI) was determined visually by dividing bananas into four categories based on the extent of the spoiled area (<25% mild, 26–50% moderate, 51–75% severe, >76% devastating), as described by Amadi et al. (2009). The DSI result for each Fusarium isolate was the mean rating of the eight replicate bananas calculated as percentages.

A second pathogenicity assay using Nicotiana benthamiana Domin seedlings was carried out for all fungal isolates. After 3 wk of incubation in PDB, the Fusarium isolates with conidiospores were harvested using the method described by (Hilton et al., 1999). An aliquot of 10 µL sample of conidial suspension (containing 108 conidia, as measured by a hemocytometer) was inoculated onto the newly emerged leaves of Nicotiana seedlings, which had been sown in the laboratory. Sterile distilled water (10 µL) was used for control seedlings. Inoculated seedlings were incubated in a moist chamber for 72 h and placed in a growth chamber with a photoperiod of 16 h light, 21 °C (d) and 8 h dark, 18 °C. The symptoms in the leaves were inspected visually and classified as no symptoms/symptoms (0/1).

The relationship of the mycotoxins (fumonisin, zearalenone and deoxynivalenol, as published by Alghuthaymi and Bahkali (2015) and the DSI index was studied with Pearson correlation analysis. Differences in the mycotoxin concentrations between the Fusarium species (which included replicated isolates) were studied with ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test.

3 Results

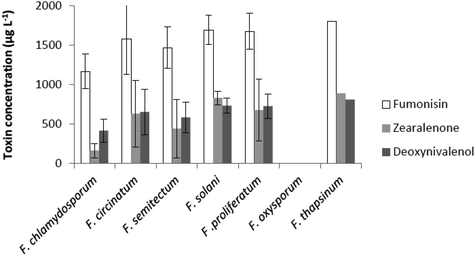

All of the species of Fusarium studied except F. oxysporum produced mycotoxins fumonisin, zearalenone and deoxynivalenol (Fig. 1). ANOVA indicated significant difference between species and separated F. oxysporum with all other species in Tukey’s test. ANOVA did not indicate any significant differences between the species when F. oxysporum was excluded. However, F. chlamydosporum generally produced the lowest concentrations of all toxins (Fig. 1).

Mycotoxins produced by different species of Fusarium isolated from banana. Error bars refer to SD of the isolates. See n from Table 1.

The pathogenicity assay with banana fruits indicated severe or devastating fruit rot symptoms (>50% DSI) for all species of Fusarium after six and seven days of incubation (Table 1). The differences between the species or isolates were minor. The non-inoculated control bananas showed no symptoms of fruit rot until the seventh day. A strong correlation (r > 0.8) was observed between the different mycotoxins. However, and no correlation appeared to exist between the DSI and mycotoxin concentrations for any day (r < 0.2) (Table 2). Ns, not significant.

Species

n

Days

1

2

4

6

7

F. chlamydosporum

2

0 ± 0

26 ± 2

49 ± 4

66 ± 6

76 ± 7

F. circinatum

3

0 ± 0

26 ± 2

47 ± 4

67 ± 1

75 ± 1

F. semitectum

5

1 ± 0

24 ± 2

50 ± 5

73 ± 7

79 ± 7

F. solani

2

3 ± 3

31 ± 6

55 ± 8

70 ± 4

75 ± 3

F. proliferatum

3

0 ± 4

27 ± 8

49 ± 6

74 ± 1

78 ± 2

F. oxysporum

2

0 ± 0

26 ± 3

47 ± 2

70 ± 3

75 ± 3

F. thapsinum

1

0 ± 0

24 ± 4

55 ± 4

75 ± 9

75 ± 6

DSI, 6th day

Fumonisin

Zearalenone

Deoxynivalenol

Fumonisin

Ns

Zearalenone

Ns

0.82

Deoxynivalenol

Ns

0.97

0.90

Combined

Ns

0.97

0.93

0.99

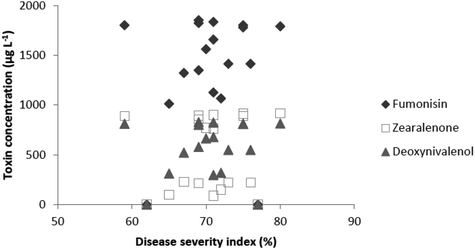

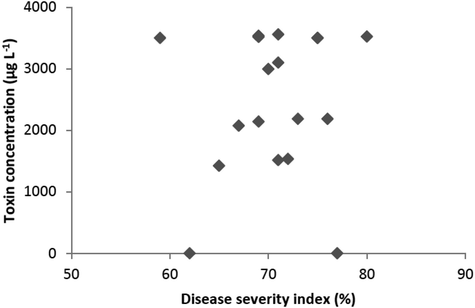

A relationship between DSI and mycotoxins was observed neither with different mycotoxins separately (Fig. 2) nor when the three different toxin concentrations were totaled (Fig. 3).

Disease severity index (DSI) in the pathogenicity assay with banana fruits in relation to the different mycotoxin concentrations produced by Fusarium isolates.

Disease severity index (DSI) in the pathogenicity assay with banana fruits in relation to combined mycotoxin concentrations produced by Fusarium isolates.

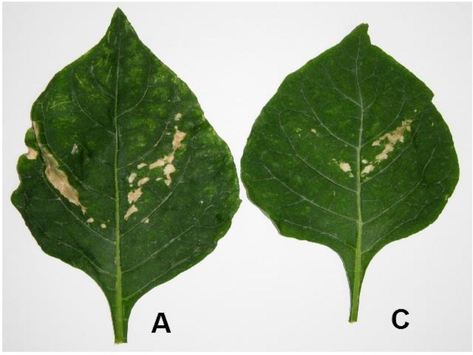

Fusarium oxysporum did not cause symptoms of infection to the leaves of Nicotiana seedlings. All other species of Fusarium (all replicate inoculations) did cause symptoms. Small spots that appeared first became distorted or chlorotic with irregular margins and shapes, finally leading to necrosis on the leaves (Fig. 4). Leaf tips turned yellow and curled downward. The infected leaves were small, and their overall growth was stunted compared to the control seedlings.

Mycotoxin-induced lesion formation in Nicotiana seedling infected with two replicate Fusarium circinatum isolate filtrates.

4 Discussion

The pathogenicity of all seven species of Fusarium isolated from infected bananas was confirmed by an assay with healthy banana fruits. Severe or devastating infection covered most of the fruits after six days of incubation. Six out of seven species produced mycotoxins (fumonisin, zearalenone and deoxynivalenol) and also showed evidence of pathogenicity to Nicotiana seedlings. Fusarium oxysporum was the only species that did not produce the mycotoxins measured. Moreover, it did not seem to be pathogenic to Nicotiana seedlings. However, it was pathogenic to banana. The differences in the pathogenicity may be explained by the different combination of toxins that the various of Fusarium species produce. Moniliformin, a less common mycotoxin that we did not measure, has been shown to be produced by F. oxysporum (Jimenez et al., 1997). This may explain the difference in the pathogenicity of F. oxysporum to Nicotiana seedlings.

Fusarium oxysporum is a common soil-borne fungus known to cause Fusarium wilt (Panama disease), one of the most devastating banana diseases worldwide (Cumagun et al., 2007). Fusarium oxysporum is known to belong to the group of virulent pathogens affecting wounded fruits (Alvindia et al., 2000). However, its genetic diversity is high, and it may be either pathogenic or non-pathogenic (Jimenez et al., 1997). The virulence depends on the genetic background of the host and the pathogen (Tarekegn et al., 2004; Tesso et al., 2004).

Phytopathogenic fungi produce a wide range of phytotoxic compounds (Stone et al., 2000). Disease symptoms often result from the effects of these fungal toxins. However, we did not observe any positive relationship between the toxin concentration and disease severity on banana, but we did observe that the species which did not produce mycotoxins also did not cause any symptoms of infection on Nicotiana seedlings. Therefore, we reject our hypothesis about the positive correlation between the toxicity symptoms and toxin concentrations.

5 Conclusion

We conclude, based on the mycotoxins produced and the pathogenicity assays, that multi-mycotoxin bioassays that allow the evaluation of the toxicity of a particular fungal infection are highly valuable and should be developed further. The virulence is a complex issue regulated by many factors and several toxins, thus, needing an assessment with bioassays and a multi-mycotoxin approach. Contamination by species of Fusarium would pose a human health hazard when contaminated fruits and the mycotoxins in them are eaten.

Funding

This research was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University through the fast-track research funding Program and the Deanship of Scientific Research at the King Saud University through Research group NO (RGP 1438-029).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Toxigenic profiles and trinucleotide repeat diversity of Fusarium species isolated from banana fruits. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip.. 2015;29:324-330.

- [Google Scholar]

- Occurrence, toxicity, and analysis of major mycotoxins in food. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2017;14:632.

- [Google Scholar]

- Symptoms and the associated fungi of postharvest diseases on non-chemical bananas imported from the Philippines. Jap. J. Trop. Agric.. 2000;44:87-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- Isolation and identification of a bacterial blotch organism from watermelon (Citrullus lanatus (Thunb.) Matsum. and Nakai) Afr. J. Agric. Res.. 2009;4:1291-1294.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fusarium mycotoxins in food. In: Chemical Contaminants and Residues in Food (Second ed.). Elsevier; 2017. p. :295-336.

- [Google Scholar]

- Multimycotoxin analysis of South African Aspergillus clavatus isolates. Mycotoxin Res. 2018:1-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Occurrence of free and conjugated 12, 13-epoxytrichothecenes and zearalenone in banana fruits infected with Fusarium moniliforme. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.. 1986;51:217-219.

- [Google Scholar]

- Population genetic analysis of plant pathogenic fungi with emphasis on Fusarium species. Philipp. Agric. Sci.. 2007;90:245.

- [Google Scholar]

- Disease suppressiveness to Fusarium wilt of banana in an agroforestry system: influence of soil characteristics and plant community. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ.. 2017;239:173-181.

- [Google Scholar]

- Inducing the rhizosphere microbiome by biofertilizer application to suppress banana Fusarium wilt disease. Soil Biol. Biochem.. 2017;104:39-48.

- [Google Scholar]

- Relationship between cultivar height and severity of Fusarium ear blight in wheat. Plant Pathol.. 1999;48:202-208.

- [Google Scholar]

- Morphological and molecular characterization of Fusarium verticillioides from rotten banana imported into Japan. Mycoscience. 2001;42:155-166.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mycotoxin production by fusarium species isolated from bananas. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.. 1997;63:364-369.

- [Google Scholar]

- Etiological agents of crown rot of organic bananas in Dominican Republic. Postharvest Biol. Technol.. 2016;120:112-120.

- [Google Scholar]

- Crown rot of bananas: preharvest factors involved in postharvest disease development and integrated control methods. Plant Dis.. 2010;94:648-658.

- [Google Scholar]

- Differentiation of Fusarium verticillioides from banana fruits by IGS and EF-1α sequence analyses. In: Mol. Divers. PCR-detection Toxigenic Fusarium Species Ochratoxigenic Fungi. 2004. p. :515-523.

- [Google Scholar]

- Toxin profile, fertility and AFLP analysis of Fusarium verticillioides from banana fruits. In: Molecular Diversity and PCR-Detection of Toxigenic Fusarium Species and Ochratoxigenic Fungi. Springer; 2004. p. :601-609.

- [Google Scholar]

- Simulation of fungal-mediated cell death by fumonisin B1 and selection of fumonisin B1-resistant (fbr) Arabidopsis mutants. Plant Cell Online. 2000;12:1811-1822.

- [Google Scholar]

- Relationship between grain development stage and sorghum cultivar susceptibility to grain mould. Afr. Plant Prot.. 2004;10:53-62.

- [Google Scholar]

- Estimation of combining ability for resistance to Fusarium stalk rot in grain sorghum. Crop Sci.. 2004;44:1195-1199.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fusarium species associated with banana fruit rot and their potential toxigenicity. Mycotoxin Res.. 1995;11:93-98.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fusarium species associated with fruit rot of banana (Musa spp.), papaya (Carica papaya) and guava (Psidium guajava) Malays. J. Microbiol.. 2012;8:127-130.

- [Google Scholar]