Translate this page into:

Mosquito abundance and physicochemical characteristics of their breeding water in El-Fayoum Governorate, Egypt

⁎Corresponding author. aalii@ksu.edu.sa (Ashraf M. Ahmed)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Objectives

This study was conducted to identify the mosquito species and the physicochemical characteristics of their breeding sites in six districts in El-Fayoum Governorate, Egypt, during October and November 2020.

Methods

Using the dipping method, mosquito larvae were collected from forty-two different breeding sites, including irrigation channels, canals, agricultural puddles, sewage tanks, stagnant water puddles, and swamps. Water temperature, pH, alkalinity, nitrite, chloride, electrical conductivity (EC), and total dissolved solids (TDS) were measured for all the studied breeding sites.

Results

The survey revealed the presence of nine mosquito species: Culex perexiguus (Theobald, 1901), Culex pipiens (Linnaeus, 1758), Culex antennatus (Becker, 1903), Culex theileri (Theobald, 1903), Anopheles multicolor (Cambouliu, 1902), Anopheles sergentii (Theobald, 1907), Ochlerotatus caspius (Pallas, 1771), Culiseta longiareolata (Macquart, 1838), and Uranotaenia ungiculata (Edwards, 1913), representing five genera. Out of these species, Cx. pipiens is the most abundant. Oc. caspius and Cx. antennatus revealed significant positive correlations with chloride, TDS, and EC. Cx. perexiguus only showed significant positive correlations with chloride.

Conclusion

Most of the recorded mosquito species are found to be able to tolerate different degrees of pollution in their breeding water. These data may contribute to establishing a database on mosquito vectors and their habitats and, hence, assist in planning and implementing the appropriate control measures in this region.

Keywords

Mosquitoes

Breeding sites

Pollution

Chloride

Electrical conductivity

Nitrite

El-Fayoum

- Ae

-

Aedes

- An

-

Anopheles

- Cl

-

Chloride

- Cm

-

Centimeter

- Cs

-

Culiseta

- Cx

-

Culex

- EC

-

Electrical conductivity

- NO2

-

Nitrite

- Oc

-

Ochlaerotatus

- r

-

Pearson correlation value

- SD

-

Standard Deviation

- spp

-

Species

- TDS

-

Total dissolved solids

Abbreviations

1 Introduction

Mosquitoes are globally undesirable arthropods as they are known vectors of many parasitic diseases like malaria and filaria, and viral diseases like Rift Valley fever, dengue fever, and yellow fever (Wilkerson et al., 2021). Mosquito vectors transmit more than 17.0 percent of mosquito-borne diseases globally and kill more than 700,000 people annually (WHO, 2020). In Egypt, the most common mosquito-borne diseases include dengue fever, Rift Valley fever, West Nile fever, and Filariasis, which have been transmitted by Cx. pipiens and Cx. perexiguus for decades (Meegan et al., 1980; Darwish and Hoogstraal, 1981; Weil et al., 1999). Moreover, An. sergentii and Anopheles pharoensis are considered malaria vectors, while An. multicolor is suspected as a possible vector (Kenawy, 1988).

El-Fayoum governorate is distinct from the Oasis, the Delta, and Upper Egypt. It is distinguished by gradually decreasing elevation and being lower than sea level. There are 1.2 million people are living there, the majority of whom work in agriculture and allied businesses. The season for the spread of diseases has been extended to eight months a year, from the end of March to the end of November, due to the ideal temperature and relative humidity. (Bassiouny, 1996,2001). In the period from 1971 to 2001 and 2004 to 2010, imported cases of malaria (from Sudan and other African nations) were reported (Dahesh and Mostafa, 2015). Therefore, continuous monitoring of mosquito populations is important for figuring out their biodiversity as well as for predicting and preventing mosquito-borne diseases (van der Beek et al., 2020).

Breeding habitats can be either artificial or natural, and they can also be categorized based on their stability as temporary, permanent, or semi-permanent (Hassan et al., 2020). Locations with stagnant water are favorable for mosquito reproduction and the development of their larvae (Ibrahim et al., 2011). Moreover, breeding habitats usually contain different types of vegetation, whether they are natural or cultivated, dense or sparse, and submerged or merged (Sowilem et al., 2017). It is proven that mosquitoes prefer habitats with short vegetation over those with tall vegetation (Chirebvu and Chimbari, 2015).

The physicochemical parameters have a significant impact on the species, density, and development of mosquito larvae and vary between the breeding sites (Gopalakrishnan et al., 2013; Nikookar et al., 2017). These parameters include temperature, pH, dissolved organic and inorganic materials, salinity, turbidity, and electrical conductivity (EC) (Gopalakrishnan et al., 2013; Kenawy et al., 2013; Elhawary et al., 2020). In this regard, the temperature should not exceed 30 °C for ideal larval development (Ibrahim et al., 2011). Many studies were conducted to determine the alkaline tendency (pH) of mosquito larvae (Abdel-Hamid et al., 2011a, 2011b, 2011c; Hassan et al., 2020; Ukubuiwe et al., 2020), and An. culicifacies larval abundance was found to have a negative correlation with pH in the range of 6 to 7 (Varun et al., 2013). Cx. modestus prefers habitats with higher salinity levels compared to An. maculipennis (Golding et al., 2015), while Cx. pusillus, Oc. caspius, and Oc. detritus prefer habitats with high levels of salinity (El-Hefni et al., 2020a, 2020b). Moreover, Nagy et al., (2021) reported a connection between the abundance of Cx. pusillus and Cx. theileri and the salinity of their habitats. Nitrite levels are usually high in seepage, agricultural drains (Nagy et al., 2021), and irrigation ditches (Elhawary et al., 2020). Cx. pipiens, Oc. caspius, and Cs. longiareolata larvae favor habitats with low levels of nitrite (about 0.6 mg/l); however, Cx. perexiguus and Cx. pusillus tolerate higher levels (up to 25 mg/l) (Kenawy et al., 2013).

Seepage habitats display the highest values of TDS and EC (El-Hefni et al., 2020a, 2020b). Armigeres and Culex larvae were collected from breeding sites with EC values greater than 10 µs/cm, while for Aedes larvae, the value ranged from 5 to 10 µs/cm. Culex spp. larval abundance increased as water EC increased. For example, Armigeres subalbatus and Cx. quinquefasciatus were found in water with a broad range of TDS (Amarasing and Dalpadado, 2014). In addition, Cx. pipiens larval abundance was linked with the EC, TDS, alkalinity, and chloride content of its habitat (Nikookar et al., 2017).

Understanding the environmental characteristics of mosquito breeding sites as well as their prevalence has been demonstrated to be a successful strategy in reducing mosquito-borne diseases (Knudsen and Slooff, 1992; Killeen et al., 2002; El-Hefni et al., 2020a, 2020b). Therefore, the association between mosquito prevalence and the physicochemical parameters of their breeding sites would help in predicting mosquito distribution and abundance. Fayoum governorate has unique topographic and climatic characteristics that encourage the proliferation of mosquitoes, which raises the likelihood of transmitting mosquito-borne disease. In the current study, mosquito diversity and prevalence in correlation with the physicochemical characteristics of their breeding sites were investigated in six administrative districts in Fayoum governorate. This may contribute to implementing appropriate mosquito vector control protocols as well as enriching the database of the mosquito community in this region.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Sites of study

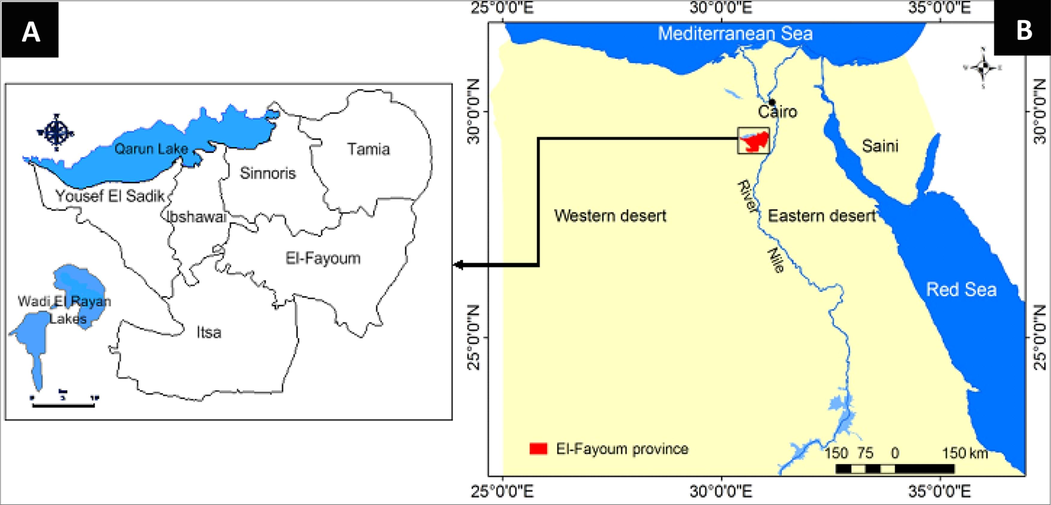

This study was conducted during October and November 2020 in El-Fayoum Governorate (30° 23′, 31° 05′, E, 29° 02′, 29° 35′, N) (Fig. 1). This Egyptian governorate has a total area of 6,068.7 km2 and a population of 3,983,912 (Egypt-statistics, 2023). The governorate is a depression in the western desert of Egypt, about 90 km southwest of Cairo. It is considered a large agricultural oasis as it is fed by the River Nile through the Baher Youssef stream, which penetrates the governorate from the eastern side and then divides into several estuaries before flowing into Qaroun Lake on the northwest side of it. The governorate is composed of six administrative districts: Sinnoris, Tamia, El-Fayoum, Atssa, Ebshawai, and Youssef El-Sedik (Abd-Elmabod et al., 2012).

A map showing El-Fayoum Governorate and its administrative districts (A) and its location in Egypt (B).

2.2 Larval collection

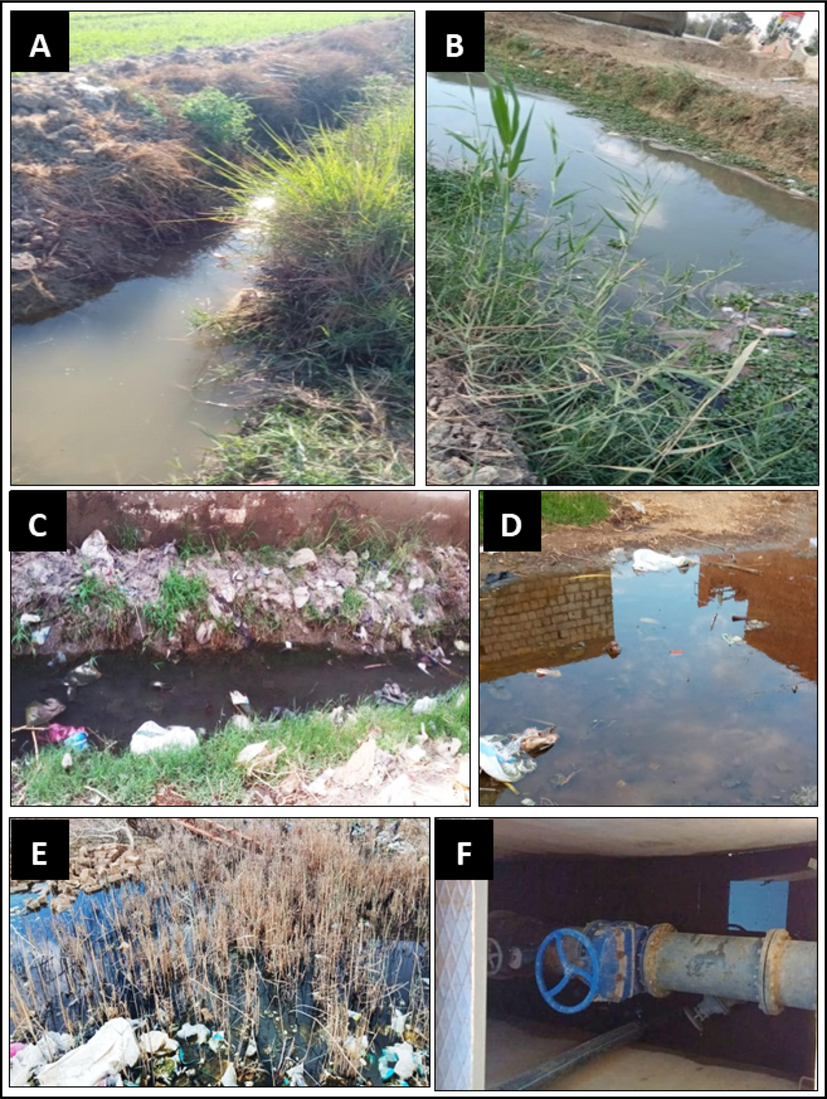

Forty-two breeding sites, including canals, sewage tanks, agricultural puddles, stagnant water puddles, and swamps, were used to gather larvae (Fig. 2). Larvae were collected by the dipping method according to (Ahmed et al., 2011) using suitable larval nets of a 20 cm in diameter iron ring attached to a 30 cm long muslin sleeve. Several varied dips (based on the width and depth of the breeding site) were gently taken from the surface. Larvae from each site were collected and transported alive to the laboratory in 500 ml plastic cups filled with the breeding site water.

Different types of studied larval habitats in El-Fayoum Governorate: A): irrigation channel; B): agricultural puddle; C): canals; D): stagnant water puddle; E): swamp; and F): sewage tank.

2.3 Physicochemical analysis

In each site, the pH and temperature were determined on-site using the HANNA HI 8314 portable device (HANNA Instruments, USA) according to the manufacturer’s manual. A sample of 500 ml of water was collected from each breeding site and sent to the laboratory to be tested for total dissolved solids (TDS) (mg/L), alkalinity (mg/L), chloride (Cl‾) (mg/L), electrical conductivity (EC) (µS/cm), and nitrite (NO2) (mg/l). Alkalinity and chloride concentrations were measured using the titration technique, TDS and EC were determined using a conductivity/TDS meter (HACH, HQ440d multi) (HACH Company, Europe), and nitrite was detected using a spectrophotometer (analytic Jena, SPECORD*50 PLUS) (Analytic Jena AG, Germany). All analyses were conducted according to Eaton et al., (2014).

2.4 Larval identification

Collected larvae were prepared for identification, according to Ahmed et al., (2011). The fourth larval instars were preserved in 70 % alcohol until primarily examined and identified using the keys developed by (Abdel-Maleck, 1956; Mattingly and Knight, 1956; Harbach, 1988). In addition, larval density in each breeding site was calculated by dividing the number of collected larvae by the number of dips (number of larvae per dip).

2.5 Analysis of data

Data were processed for statistical analysis using SPSS (version 26) and Microsoft Excel worksheets (Microsoft Office 2010) for Windows. Descriptive statistics were used to calculate the abundance percentage of each mosquito species collected from each district in the study area. Line charts were drawn to depict the physicochemical parameters. The mean and standard deviation (SD) were calculated to show ranges within all sites. The connection between the density of larvae and the physicochemical parameters of their habitats was determined by using Pearson correlation analysis (significant at P ≤ 0.05).

3 Results

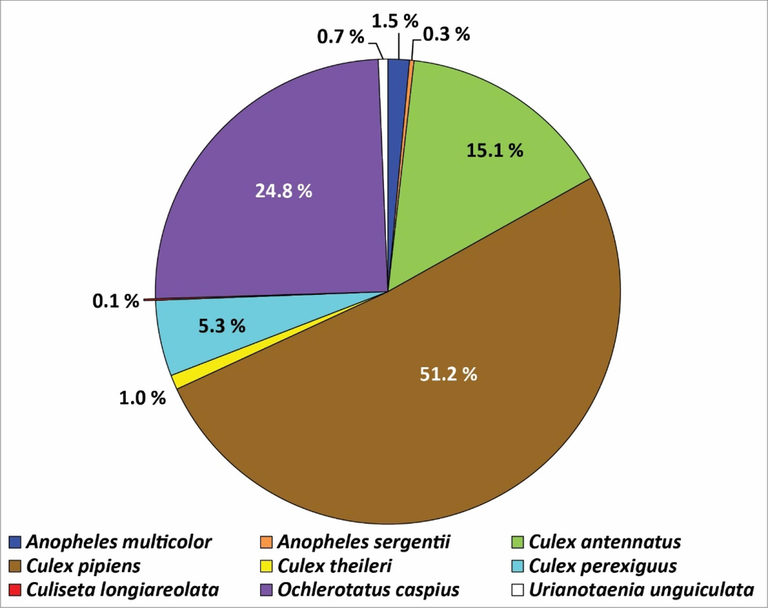

The 2559 collected larvae were classified into nine species belonging to five genera. These larvae were collected from 42 breeding sites in Fayoum governorate. As shown in Fig. 3, the overall relative distribution of each mosquito species varies among the studied breeding sites. The current study found that Culex is the most prevalent genus in the studied area, constituting 72.6 % (1858 larvae) of the total collected samples. Cx. pipiens is the most abundant species, accounting for 51.2 % (1311 larvae), followed by Cx. antennatus, 15.1 % (386 larvae), Cx. perexiguus, 5.3 % (135 larvae), and Cx. theileri, 1 % (of 26 larvae). Oc. caspius comes next and accounts for 24.8 % (635 larvae), followed by Anopheles multicolor, which accounts for 1.5 % (38 larvae), and An. sergentii, which accounts for 0.3 % (8 larvae), while Ur. unguiculata accounts for only 0.7 % (17 larvae). Cu. longiareolata was the scarcest species, with only 3 larvae encountered, which constitute 0.1 % of the total collected size.

The relative abundances of mosquito larval species throughout the governorate.

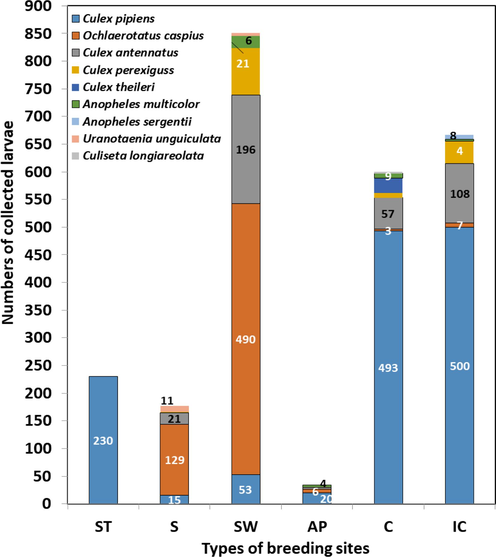

The species distribution of mosquito larvae varied based on the studied habitat types. As shown in Fig. 4, Cx. pipiens was recorded from all sites; it was also the most abundant species in the irrigation canals, and additionally, it was the only species collected from sewage tanks. Results also revealed that Oc. caspius was the most abundant in stagnant water puddles and swamps. On the other hand, other species were less abundant and varied among the different types of habitats.

Number of mosquito larvae collected from different habitat types throughout El-Fayoum Governorate. ST: Sewage tank; S: swamps; SW: stagnant water; AP: agricultural puddles; C: canals; IC: irrigation canals.

The data also uncovered variations in species distribution in the studied districts (Table 1). Within the breeding habitats, canals were the most frequent type, followed by stagnant water puddles, which were noticeably found within residential areas. Generally, the current study observed that breeding sites with higher larval densities were near houses and sheds. Most of the breeding habitats were not or partially shaded, with varied depth and size. Grasses, as well as small to medium plants, were observed growing in water bodies, while a few of the breeding sites that contained large plants had very low larval densities. It was also noticeable that residential garbage was spreading in stagnant water puddles and canals.

Species

Studied districts

Sinnuris

Abshway

Youssef El-Sedik

Fayoum

Atssa

Tamiya

An. multicolor

1.3

0.0

7.5

2.5

0.0

0.7

An. sergentii

0.0

0.0

6.0

0.0

0.0

0.0

Cx. antennatus

8.6

0.5

0.0

24.8

69.8

21.7

Cx. pipiens

73.6

98.7

30.6

12.3

14.8

0.0

Cx. theileri

2.5

0.0

9.0

0.0

0.0

0.0

Cx. perexiguss

0.0

0.8

7.5

10.3

0.0

9.8

Cu. longiareolata

0.0

0.0

2.2

0.0

0.0

0.0

Oc. caspius

14.1

0.0

37.3

49.4

8.1

67.8

Ur. unguiculata

0.0

0.0

0.0

0.7

7.4

0.0

Total

100

100

100

100

100

100

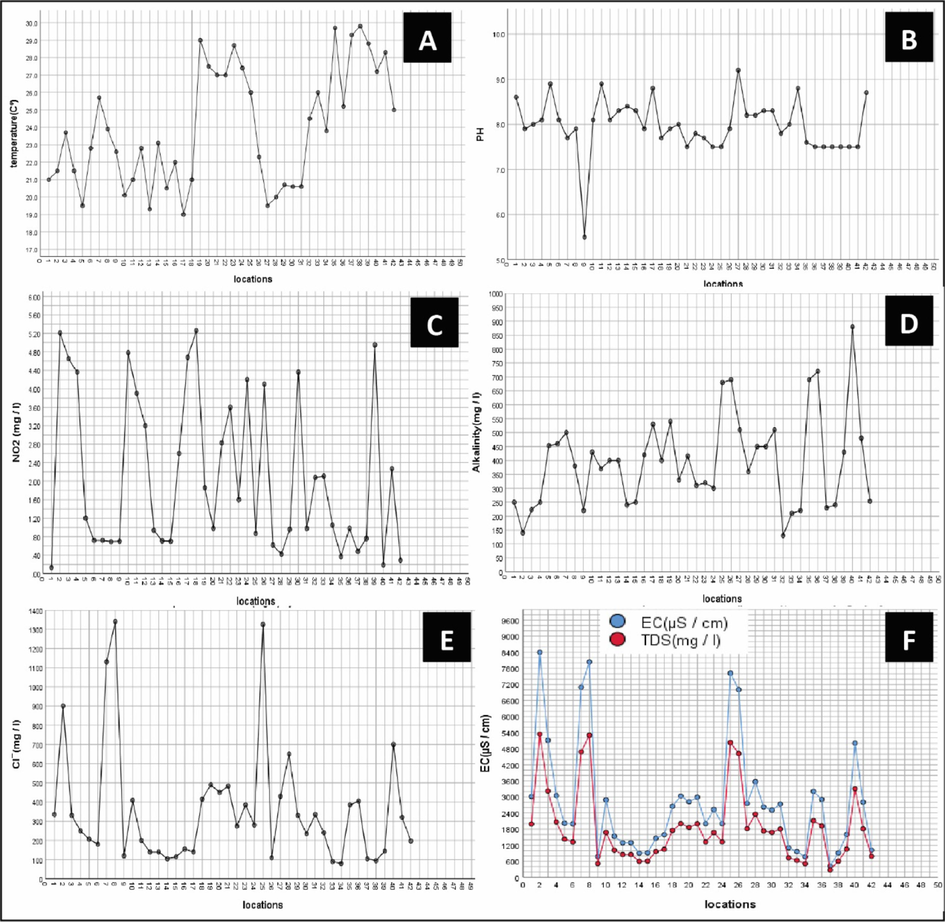

The physicochemical characteristics of the 42 studied breeding sites were recorded, and the data showed significant variation amongst the breeding sites (Table 2 and Fig. 5). Results revealed variation in temperature from 19 °C to 29.8 °C, and the pH varied from acidic to alkaline (5.5 to 9.2), with a mean value of 7.97 (alkaline tendency) (Table 2). Oc. caspius and Cx. pipiens were the only two species recorded in the breeding sites at pH 5.5 (acidic medium). It was also noticeable that the TDS and EC were high in the habitats that contained seepage water. Moreover, data showed a link between larval relative abundance and physicochemical parameters in the governorate. As shown in Table 3, mosquito larvae tolerated a wide range of temperatures in different habitats. Additionally, all larval species showed an alkaline tendency. The larvae of An. sergentii showed the highest intolerance to nitrite concentrations, while Oc. caspius showed the highest tolerance to the higher values of TDS and EC concentrations.

Temp (C°)

pH

NO2

(mg/l)Alkalinity (mg/l)

EC

(µS/c)Cl‾

(mg/l)TDS

(mg/l)

Min-max.

(19–29.8)

(5.5–9.2)

(0.13–5.26)

(130–880)

(418–8400)

(80–1340)

(276–5344)

Mean ± SD

23.9

± 0.377.98

± 0.62.09

± 1.71396.81

± 167.032829.90

± 2078.13360.71

± 310.91859.90

± 1351.97

Measured physicochemical characteristics within the 42-breeding site; A: temperature. B: pH. C: nitrite. D: alkalinity. E: chloride. F: EC and TDS.

Mosquito species

N

Physicochemical characteristics (means ± SD)

Temp

(C°)pH

NO2 (mg/l)

Alkalinity (mg/l)

EC

(µS/cm)Cl‾

(mg/l)TDS

(mg/l)

Cx. pipiens

19

24.93

±3.7347.811

±0.742.091

±1.764438.63

±198.852660.53 ± 1482.8

341.89 ± 171.1

1747.63 ± 971.31

Oc. caspius

11

23.273

±1.967.864

±0.882.186

±1.939314.82

±157.454226.18 ± 3102.9

556.82 ± 508.4

2761.45 ± 2015.5

Cx. antennatus

12

23.53

±2.708.125

±0.461.557

±1.338351.58

±104.982751.83 ± 2426.8

375.75 ± 419.2

1830

±1599.6

Cx. perexiguss

10

23.54

±3.1497.99

±0.4282.218

±1.5409.9

±123.463463.2

±2772.4421.9

±445.52297

±1823.7

An. multicolor

6

21.85

±3.468.25

±0.553.34

±10.98430

±95.492587.83 ± 517.03

300.67 ± 110.2

1680.83 ± 338

Cx. theileri

2

23.6

±50.097.85

±0.4950.305

±0.016620

±367.694189

±1016.8475 ± 35.35

2630.5

±671.04

An. sergentii

2

20.65

±0.078.25

±0.070.97

±0.014480

±42.422675

±770.78332.5

±3.531765.5

±51.61

Ur. ungiculata

2

21.05

±1.348

±0.143.69

±10.54425

±7.072172.5

±1013.3282

±179.61317.5

±504.16

Cu. longiareolata

1

22.3

7.9

4.1

690

7000

110

4620

It is worth mentioning that there was a significant positive correlation between the prevalence of both Oc. caspius and Cx. antennatus and EC, Cl‾, and TDS (P < 0.05) as tabulated in Table 4 using Pearson correlation, while data revealed a negative correlation between the same species and pH and NO2 (P > 0.05). In the same regard, Cx. pipiens showed negative correlations with pH, EC, Cl‾, and TDS (P > 0.05). The occurrences of Cx. perexiguus showed a positive correlation with Cl‾ only (P < 0.05). Other than that, the correlations between other species and those parameters can’t be established since they were encountered in small numbers at limited sites.

N

Temp.

(C°)pH

NO2 (mg/l)

Alkalinity(mg/l)

EC

(µS/cm)Cl-

(mg/l)TDS

(mg/l)

Cx. pipiens

Pearson Correlation

19

0.402

−0.089

0.043

0.057

−0.190

−0.164

−0.186

Sig. (2-tailed)

0.088

0.718

0.862

0.818

0.437

0.503

0.445

Oc. caspius

Pearson Correlation

11

0.565

−0.033

−0.277

0.396

0.625*

0.730*

0.637*

Sig. (2-tailed)

0.070

0.923

0.410

0.228

0.040

0.011

0.035

Cx. antennatus

Pearson Correlation

12

0.083

−0.199

−0.129

0.288

0.659*

0.710*

0.653*

Sig. (2-tailed)

0.797

0.536

0.690

0.364

0.020

0.010

0.021

Cx. perexiguss

Pearson Correlation

10

−0.090

0.069

−0.428

−0.007

0.594

0.702*

0.595

Sig. (2-tailed)

0.806

0.849

0.217

0.985

0.070

0.024

0.070

4 Discussion

This study was conducted to investigate the correlation between mosquito relative abundance and their habitats’ physicochemical parameters as well as to update the database of mosquito prevalence in El-Fayoum Governorate, Egypt. This governorate is unique in that its geography is distinct in nature from Upper Egypt and the Oasis. In addition to its relatively lower altitude near sea level and the gradual inclination of its topography from southeast to northwest, it also has a population of about 1.20 million people, most of whom work in farming fields and agriculture (Bassiouny, 1996). In this area, the transmission season of mosquito-borne diseases is extended to 8 months every year (from March to November); this is unfortunately due to the moderate climate and higher relative humidity (CLIMATE DATA, 2023). These constitute very convenient conditions to encourage mosquito breeding and prevalence (El-Hefni et al., 2020a, 2020b). As a result, the governorate has been designated as a dangerous area for mosquito-borne diseases such as malaria, filaria, Rift Valley, and dengue fevers (Meegan et al., 1980; Darwish and Hoogstraal, 1981; Bassiouny, 2001, Abdel-Hamid et al., 2011a, 2011b, 2011c, Dahesh and Mostafa, 2015, El-Hefni et al., 2020a, 2020b, Gaber et al., 2022), compared to the rest of the governorates in Egypt.

Nine larval species were identified in the forty-two breeding sites of the targeted six administrative districts: An. multicolor, An. sergentii, Oc. caspius, Cx. pipiens, Cx. antennatus, Cx. theileri, Cx. perexiguus, Cu. longiareolata, and Ur. ungiculata. These mosquito species belong to five genera: Culex, Anopheles, Culiseta, Aedes, and Uranotaenia. These genera are the most common in Egypt, and the majority of them are important vectors for both human and animal diseases (Harbach et al., 1988, Dahesh and Mostafa, 2015, El-Hefni et al., 2020a, 2020b). This study recorded more than one species that had not been recorded in this governorate during the last 20 years. For example, Mostafa et al., (2002) surveyed the Sinnuris district but didn’t record Cx. theileri, Cx. perexiguus, Oc. caspius, or Ur. ungiculata. Selim and Hammad (2019) surveyed the Wadi Al-Rian national reserve but didn’t detect Cx. theileri, Oc. caspius, Cu. longiareolata, or Ur. ungiculata. El-Hefni et al., (2020a, 2020b) surveyed the six districts of the governorate but didn’t detect Cx. antennatus, Cx. theileri, Cu. longiareolata, or Ur. ungiculata. Eltaly et al., (2022) surveyed the four sites belonging to three districts (Tamiya, Youssef El-Sedik, and Abshway) but didn’t detect Cx. theileri, Cx. perexiguus, An. multicolor, Ur. ungiculata, or Cu. longiareolata.

This study provides evidence that Cx. pipiens is the most abundant species throughout the governorate, especially in Abshway district. It is also abundant in many other Egyptian governorates, such as El-Sharqiya (Abdel-Hamid et al., 2009), El-Gharbia (Abdel-Hamid et al., 2011a, 2011b, 2011c), El-Menoufia (Abdel-Hamid et al., 2011a, 2011b, 2011c), Qalyubiya (Ibrahim et al., 2011), Ismailia (Abdel-Hamid et al., 2011a, 2011b, 2011c), Cairo (Kenawy et al., 2013), Suez Canal zone (Sowilem et al., 2017, El-Hefni et al., 2020a, 2020b), and Giza (Nagy et al., 2021). Similar observations were recorded in El-Fayoum governorate (Selim; Hammad 2019, El-Hefni et al., 2020a, 2020b, Eltaly et al., 2022). We may attribute this high prevalence of Cx. pipiens to its ability to tolerate extreme water conditions, such as wide ranges of temperature, alkalinity, nitrite, and pH prevailing in their breeding habitats. This maximizes the risk of frequent incidences of dangerous epidemics of mosquito-borne diseases in Egypt, like lymphatic filariasis (Abdel-Hamid et al., 2011a, 2011b, 2011c), West Nile virus, Sindbis viruses, Rift Valley fever, and St. Louis encephalitis (Turell, 2012).

Our data also showed that Oc. caspius and Cx. antennatus are the 2nd and 3rd most abundant species throughout El-Fayoum governorate, respectively, especially in Tamiya and Atssa districts, respectively. They were also recorded in other districts in the governorate (El-Hefni et al., 2020a, 2020b, Eltaly et al., 2022) and throughout several other Egyptian governorates (Abdel-Hamid et al., 2011a, 2011b, 2011c, Ibrahim et al., 2011, Kenawy et al., 2013, Sowilem et al., 2017, Selim; Hammad 2019, El-Hefni et al., 2020a, 2020b). Cx. perexiguus, An. multicolor, Cx. theileri, Ur. unguiculata, An. sergentii, and Cu. longiareolata, were the least abundant in the six targeted districts. These mosquito species were also recorded in other governorates in Egypt (Abdel-Hamid et al., 2009, Abdel-Hamid et al., 2011a, 2011b, 2011c, Ibrahim et al., 2011, Elhawary et al., 2020).

Urbanization is one of the major factors that greatly affects mosquito breeding in their natural habitats (Knudsen and Slooff, 1992). In this context, most of the collected specimens were encountered in canals and stagnant water puddles that were found next to residential areas. These breeding habitats were filled with water associated with human activities and garbage. This leads us to conclude with confidence that the presence of bad sanitation practices in many of the residential areas in the region and the lack of social awareness among locals appear to be responsible for mosquito reproduction and prevalence. Furthermore, in agreement with Chirebvu and Chimbari (2015), the current study proved that mosquitoes in general prefer breeding sites with vegetation consisting of small to medium plants and grasses compared to sites that contained heavy and tall plants.

The physicochemical characteristics of mosquito breeding habitats also greatly affect mosquito breeding in their sites (Gopalakrishnan et al., 2013, Alkhayat et al., 2020, Elhawary et al., 2020). The results of the current study showed a range of the breeding sites’ temperatures from 19.0 °C to 29.8 °C, with a mean of 23.92 °C, which is favorable for mosquito development (Loetti et al., 2011, Mamai et al., 2018). Similar to Salit et al., (1996), our data showed a pH range from 5.5 to 9.2, and only one site displayed acidic habitat (pH 5.5) which contained Culex pipiens and O. caspius larvae. Ukubuiwe et al., (2020) proved that mosquito larval development is faster at pH 7, but slower at acidic (pH 4) or extreme alkaline (pH 10). High contents of nitrite and nitrate also greatly affect mosquito breeding in their habitats (Laird, 1988), and similar to Salit et al., (1996) we recorded mosquitoes in sites with a wide range of nitrite concentrations. Data also showed a high concentration of TDS and EC in the types of habitats that contained seepage water, and that Oc. caspius and the majority of culicine larvae were recorded in these habitats. Most of these sites were puddles next to houses that contained seepage and sewage water, which, in fact, may indicate that these species prefer this type of habitat. Thus, we could conclude that mosquito larvae can tolerate different degrees of pollution, as reported by several studies (Salit et al., 1996, Ibrahim et al., 2011, Nagy et al., 2021). On the other hand, Anopheline species could not tolerate these polluted habitats, as shown in our results and by Oringanje et al., (2011).

5 Conclusion

This study investigated 42 breeding sites for mosquitoes in Fayoum governorate and reported nine mosquito species. Out of them, C. pipiens was the most abundant species. Cx. theileri, Cu. longiareolata, and Ur. ungiculata were recorded in El-Fayoum Governorate for the first time during the last 30 years. The water temperature at all breeding sites ranged from 19.0 to 29.8 °C. The concentrations of NO2 (mg/L), Cl- (mg/L), alkalinity (mg/L), TDS (mg/L), and EC varied between the different habitats. The TDS and EC values were high in habitats that contained seepage water. Oc. caspius and Cx. antennatus had significant positive correlations with EC, Cl- and TDS, while Cx. perexiguus showed only a positive correlation with Cl-. Finally, all recorded mosquito larvae preferred alkaline habitats. Further studies will focus on the correlation between mosquito abundance and other vital factors like environmental, meteorological, and biological factors, as well as vegetation cover and aquatic bodies.

This could be useful in creating a precise disruption map for mosquito vectors and, consequently, in putting into appropriate efficient mosquito control strategies in Egypt.

Disclosure of funding

This study was funded by the Researchers' Supporting Project number (RSPD2023R695), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Adel. A. Abo El Ela: Conceptualization, Data curation, Supervision, Writing – original draft. Azza Mostafa: Investigation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. Eman. A. Ahmed: Resources, Software, Validation. Abdelwahab Khalil: Supervision, Validation, Data curation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. Mohamed Ghonaim: Software, Writing – review & editing, Validation. Ashraf M. Ahmed: Funding acquisition, Data curation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Researchers’ Supporting Project number (RSPD2023R695), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, for financial support of this study.

Declaration of competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Spatial distribution and abundance of culicine mosquitoes in realtion to the risk of filariasis transmission in El-Sharqiya Governorate, Egypt. Egypt. Acad. J. Biol. Sci., e. Med. Entomol. Parasitol.. 2009;1(1):39-48.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) in El-Gharbia Governorate, Egypt: their spatial distribution, abundance and factors affecting their breeding related to the situation of lymphatic Filariasis. Egypt. Acad. J. Biol. Sci., e. Med. Entomol. Parasitol.. 2011;3(1):9-16.

- [Google Scholar]

- Geographical distribution and relative abundance of culicine mosquitoes in relation to transmission of lymphatic Filariasis in El-Menoufia Governorate. Egypt. J. Egypt. Soc. Parasitol.. 2011;41(1):109-118.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) in relation to the risk of disease transmission in El-Ismailia Governorate, Egypt. J. Egypt. Soc. Parasitol.. 2011;41(2):347-356.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluating soil degradation under different scenarios of agricultural land management in mediterranean región. Nat. Sci.. 2012;10(10):103-116.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mosquitoes of northern Sinai (Diptera: Culicidae) Bull. Soc. Entomol. Egypte.. 1956;60:97-106.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mosquito vectors survey in the Al-Ahsaa district of eastern Saudi Arabia. J. Insect Sci.. 2011;11(1):176.

- [Google Scholar]

- Charaterization of mosquito larval habitats in Qatar. Saudi J. Biol. Sci.. 2020;27(9):2358-2365.

- [Google Scholar]

- Vector mosquito diversity and habitat variation in a semi urbanized area of Kelaniya in Sri Lanka. Int. J. Entomol. Res.. 2014;2(1):15-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bioenvironmental and meteorological factors related to the persistence of malaria in Fayoum Governorate: a retrospective study. EMHJ- East. Mediterr. Health. J.. 2001;7(6):895-906.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bassiouny, H., 1996. Determination of epidemiological factors causing the persistence of malaria transmission in Fayoum goveronorate, final report Alexandria. WHO Reginal Office for the Eastern Mediterranean (1996).

- Characteristics of Anopheles arabiensis larval habitats in Tubu village. Botswana. J. Vector. Ecol.. 2015;40(1):129-138.

- [Google Scholar]

- CLIMATE DATA. 2023. https://en.climate-data.org/africa/egypt/faiyum-governorate/faiyum-5569/#weather (Accessed January 10, 2023).

- Reevaluation of malaria parasites in El-Fayoum Governorate, Egypt using rapid diagnostic tests (RDTS) J. Egypt. Soc. Parasitol.. 2015;45(3):617-628.

- [Google Scholar]

- Arboviruses infecting humans and lower animals in Egypt: a review of thirty years of research. J. Egypt. Public. Health. Assoc.. 1981;56(1–2) (1–2):1-112.

- [Google Scholar]

- Eaton, A.D., Clesceri, L.S., Greenberg, A.E., 2014. Standard methods: for the examination of water and wastewater. Washington, DC 20005. http://localhost:8080/xmlui/handle/123456789/4443, Am. J. Public Health.

- Egypt-statistics, 2023. Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics. https://www.capmas.gov.eg/Pages/populationClock.aspx. Retrieved October, 2023.

- Culicine mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) communities and their relation to physicochemical characteristics in three breeding sites in Egypt. Egypt. J. Zool.. 2020;74(74):30-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hyperspectral based assessment of mosquito breeding water in Suez Canal zone, Egypt. Environ. Remote Sens. Egypt 2020:183-207.

- [Google Scholar]

- El-Hefni, A.M., El-Zeiny, A.M., Effat, H.A., 2020. Environmental sensitivity to mosquito transmitted diseases in El-Fayoum using spatial analyses. E3S Web of Conferences, EDP Sciences.

- Phototoxicity of eosin yellow lactone and phloxine B photosensitizers against mosquito larvae and their associated predators. Saudi J. Biol. Sci.. 2022;1:1-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Dengue fever as a reemerging disease in upper Egypt: diagnosis, vector surveillance and genetic diversity using RT-LAMP assay. PLoS ONE.. 2022;17(5):1-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Identifying biotic interactions which drive the spatial distribution of a mosquito community. Parasit. Vectors. 2015;8(1):1-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Physicochemical characteristics of habitats in relation to the density of container-breeding mosquitoes in Asom. India. J. Vector. Borne. Dis.. 2013;50(3):215.

- [Google Scholar]

- The mosquitoes of the subgenus Culex in southwestern Asia and Egypt (Diptera: Culicidae) Contributions of the American Entomological Institute.. 1988;24(1):1-240.

- [Google Scholar]

- Records and notes on mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) collected in Egypt. Mosq Syst.. 1988;20(3):317-342.

- [Google Scholar]

- Characterization and distribution of larval habitats of Culex pipiens complex (Diptera: Culicidae) vectors of West Nile virus in Tabuk town, Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Mosq. Res.. 2020;7(60–68

- [Google Scholar]

- Mosquito breeding sources in Qalyubiya Governorate, Egypt. Egypt. Acad. J. Biol. Sci., e. Med. Entomol. Parasitol.. 2011;3(1):25-39.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anopheline mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) as malaria carriers in AR Egypt “History and present status”. J. Egypt. Public Health Assoc.. 1988;63(1–2):67-85.

- [Google Scholar]

- Physico-chemical characteristics of the mosquito breeding water in two urban areas of Cairo governorate. Egypt. J. Entomol. Acarol. Res.. 2013;45(3):e17.

- [Google Scholar]

- Advantages of larval control for African malaria vectors: low mobility and behavioural responsiveness of immature mosquito stages allow high effective coverage. Malar J.. 2002;1(1):1-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Vector-borne disease problems in rapid urbanization: new approaches to vector control. Bull. World Health Organ.. 1992;70(1):1.

- [Google Scholar]

- The natural history of larval mosquito habitats. London: Academic Press Ltd; 1988. ISBN: 9780124340053

- Development rates, larval survivorship and wing length of Culex pipiens (Diptera: Culicidae) at constant temperatures. J. Nat. Hist.. 2011;45(35–36):2203-2213.

- [Google Scholar]

- Optimization of mass-rearing methods for Anopheles arabiensis larval stages: effects of rearing water temperature and larval density on mosquito life-history traits. J. Econ. Entomol.. 2018;111(5):2383-2390.

- [Google Scholar]

- Experimental transmission and field isolation studies implicating Culex pipiens as a vector of Rift Valley fever virus in Egypt. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg.. 1980;29(6):1405-1410.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mosquito species and their densities in some Egyptian governorates. J. Egypt. Soc. Parasitol.. 2002;32(1):9-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- Water quality assessment of mosquito breeding water localities in the Nile Valley of Giza governorate. J. Environ. Sci. Mansoura Univ.. 2021;50(1):1-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Correlation between mosquito larval density and their habitat physicochemical characteristics in Mazandaran Province, northern Iran. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases.. 2017;11(8):1-19.

- [Google Scholar]

- Vector abundance and species composition of Anopheles mosquito in Calabar. Nigeria. J. Vector. Borne. Dis.. 2011;48(3):171.

- [Google Scholar]

- Salit, A., Al-Tubiakh, S., El-Fiki, S., Enan, O., Wildey, K., 1996. Physical and chemical properties of different types of mosquito aquatic breeding places in Kuwait State. In: Proceedings of the Second international Conference on urban Pests.

- Distribution of mosquitoes along Wadi El-Rayan protected area. J. Nucl. Technol. Appl. Scie.. 2019;7(1):237-248.

- [Google Scholar]

- Species composition and relative abundance of mosquito larvae in Suez Canal Zone. Egypt. Asian J. Biol.. 2017;3(3):1-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Members of the Culex pipiens complex as vectors of viruses1. J. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc.. 2012;28(4s):123-126.

- [Google Scholar]

- Quantifying the roles of water pH and hardness levels in development and biological fitness indices of Culex quinquefasciatus Say (Diptera: Culicidae) J. Basic. Appl. Zool.. 2020;81(1):1-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Taxonomy, ecology and distribution of the mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) of the Dutch Leeward Islands, with a key to the adults and fourth instar larvae. Contrib. Zool.. 2020;89(4):373-392.

- [Google Scholar]

- Characteristics of the larval breeding sites of Anopheles culicifacies sibling species in Madhya Pradesh. India. Internl. J. Malar. Res. Rev.. 2013;1(5):47-53.

- [Google Scholar]

- A longitudinal study of Bancroftian filariasis in the Nile Delta of Egypt: baseline data and one-year follow-up. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg.. 1999;61(1):53-58.

- [Google Scholar]

- WHO, 2020. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/vector-borne-diseases. Retrieved January 10, 2023, 2023.

- Mosquitoes of the World. Johns Hopkins University Press; 2021.