Translate this page into:

Morphological and molecular characterizations for the developmental stages of Hysterothylacium species infecting Argyrops spinifer

⁎Corresponding authors at: Department of Biology, College of Sciences and Humanities, Prince Sattam Bin Abdulaziz University, Al-Kharji, Saudi Arabia (Q. AlGabbani). q.algbbani@psau.edu.sa (Rewaida Abdel-Gaber)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Hysterothylacium species are perhaps the most abundant and diverse group of marine ascaridoids; however, their life cycle and specific identification in larval stages are difficult. In this study, three members of the genus Hysterothylacium (Ward and Magath, 1917) are morphologically described from the digestive tract of Argyrops spinifer, genetically characterized and their relationship with related taxa are compared and discussed. The former species (Hysterothylacium reliquens Norris and Overstreet, 1975) (p = 10%) is mainly characterized by its large body (male 30.89, females 34.15 mm long), the shape of lips, the presence of lateral alae, a short caecum, and a long ventricular appendix, length of spicules, number and distribution of genital papillae, and tail tip with numerous spines. The other species [fourth (L4) and third (L3) larval stages] (p = 46.66, 26.66%, respectively) are mainly characterized by body length (18.21 and 6.20 mm long, respectively), distinct three lips for L4 and poorly developed for L3, a shorter caecum than the ventricular appendix, tail tip lacks any distinct cuticular projections. Molecular tools were done via sequencing and analyzing target regions of ribosomal [internal transcribed spacer (ITS) and small ribosomal DNA (18S)] and mitochondrial [cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (COX1)]. These sequences demonstrate discrimination at the species level and confirm the validity of species determined by morphological identification. All sequenced parasite samples were identified as H. reliquens based on nucleotide sequence comparisons with other ascaridoids. In these analyses, Raphidascarididae formed a sister group to Anisakidae with strong nodal support. On MP trees, a genus-specific cluster with a well-support value was delineated in genera Raphidascaris, Contracaecum, and Hysterothylacium. This study demonstrated that selected gene regions of H. reliquens yielded unique sequences (gbl MZ148786.1, MZ148788.1, and MZ148789.1) that confirmed its taxonomic position in Raphidascarididae. Therefore, morphological and molecular tools are important for accurate diagnosis of genus and species of ascaridoids.

Keywords

Ascaridida

Morphology

Phylogeny

Argyrops spinifer

Saudi Arabia

1 Introduction

The family Sparidae, commonly known as sea breams, inhabits both tropical and temperate coastal water. Most sea breams are excellent food fish and are of notable importance to both commercial and recreational fisheries throughout their range (Sommer et al., 1996). Of the various species of sea bream, the king soldier bream Argyrops spinifer, is distributed in the Red Sea, Eastern coast of Africa, and Northern Australia.

Nematodes of the family Anisakidae, and particular species of the genera Anisakis, Pseudoterranova, and Contracaecum, are of medical and socioeconomic concern globally as they are the causative agents of a fish-borne zoonosis called anisakidosis (Bao et al., 2019). Besides the presence of anisakids in fish, the occurrence of other ascaridoid nematodes belonging to the family Raphidascarididae, i.e. Hysterothylacium aduncum (Rudolphi, 1802) Deardorff and Overstreet, 1981 is also very common (Klimpel and Rückert, 2005). Hysterothylacium species use fish as the final host, whilst Anisakis spp., Pseudoterranova spp., and Contracaecum spp. use cetaceans, seals, and seals/fish-eating birds, respectively in their life cycle (Berland, 1991). The genus Hysterothylacium Ward and Magath (1917) is frequently mistaken with the genus Contracaecum Railliet and Henry (1912). As, the latter genus of Contracaecum possesses an excretory pore next to the ventral interlabium, in the former genus Hysterothylacium this pore is located on the nerve ring region (Lopes et al., 2011).

The genus Hysterothylacium includes 89 accepted species, one taxon inquirendum, two nomina dubia, and ten unaccepted species (WoRMS, 2021), but GBIF (2021) enlisted 97 species in this genus. Most of these species are based on morphology only, providing a lack of differential characters that makes specific identification difficult. Molecular studies have been proven to be useful for accurate identification of Hysterothylacium species using DNA sequencing of ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) regions and the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (COX1) and (COX2) genes (Simsek et al., 2018).

Although numerous studies on marine fish parasites have been conducted, little is known about ascaridoids in the host fish in Saudi Arabia. Therefore, the present study aimed to through more light on ascaridoid species present in a frequently consumed fish Argyrops spinifer inhabiting the Red Sea coast in Jeddah Province, Saudi Arabia. An additional aim was to characterize it using morphological and genetic analyses focusing on the proper identification at the specific level.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Fish sampling and parasitological examination

In total, 40 samples of the king soldier bream Argyrops spinifer (Family: Sparidae) were purchased from fish markets, the Red Sea, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, during the period of January-April 2021. Fish were frozen and sent for parasitological inspection to Laboratory for Parasitology Research. Fish were dissected and examined micro- and macroscopically for endoparasitic nematodes. Gastrointestinal tract and body cavity were inspected using a dissecting microscope (Nikon SMZ18, NIS ELEMENTS software). All nematodes were isolated and preserved in 70% ethanol. Ten representative specimens were selected and observed at different magnifications using a Leica DM 2500 microscope (NIS ELEMENTS software, version 3.8), and subjected to DNA sequencing to identify this species. The recovered nematodes were morphologically identified according to Berland (1991). Measurement ranges were recorded in millimeters with means in parentheses. Quantitative descriptors for parasite populations including prevalence (P), mean intensity (mI), and mean abundance (mA) were calculated according to Bush et al. (1997).

2.2 Molecular analysis

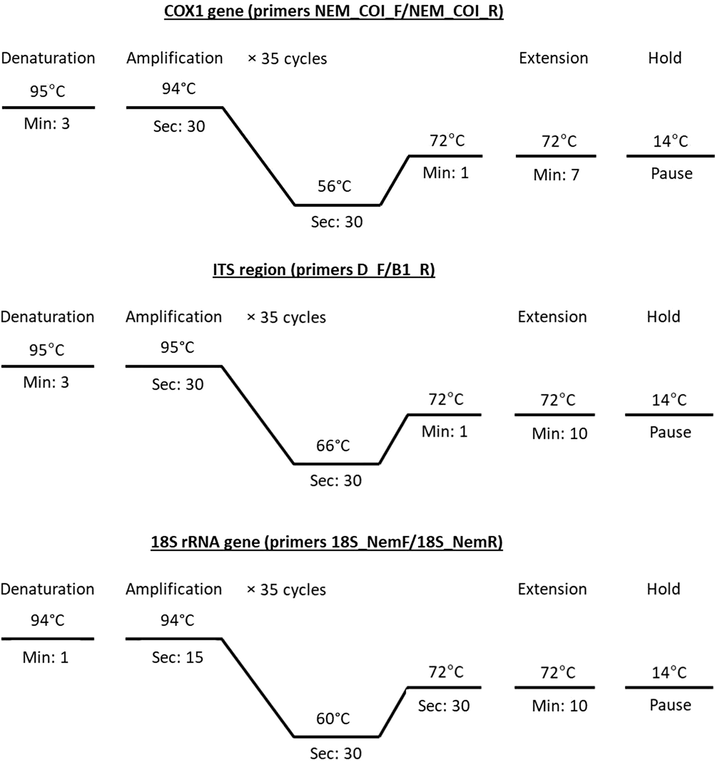

Genomic DNA was extracted from the preserved adult specimens using a QIAamp® DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following manufacturer steps. PCR targeting COX1 and 18S rRNA genes and ITS region. COX1 gene was amplified using primers NEM_COI_F (forward; 5′–GGW SMA MMA AAT CAT AAA GAT ATT GG–3′) and NEM_COI_R (reverse; 5′–GTA ATA GCM MCH GCY AAH ACM G–3′) (Malysheva et al., 2016). 18S rRNA gene was amplified using 18S_NemF (forward; 5′–TGT CTC AAA GAT TAA GCC ATG C-3′) and 18S_NemR (reverse; 5′–GGG CGG TGT GTA CAA AGG–3′) (Avó et al., 2017). ITS region was amplified using D_F (forward; 5′–GGC TYR YGG NGT CGA TGA AGA ACG CAG–3′) and B1_R (reverse; 5′–GCC GGA TCC GAA TCC TGG TTA GTT TCT TTT CCT–3′) (Bachellerie and Qu, 1993). PCR reaction (in a volume of 20 µl) was performed in 2 μl of genomic DNA, 0.6 μl of each primer, 4 μl Master Mix (5 × FIREPol® Master Mix Ready to Load; Solis BioDyne), and completed by nuclease-free water. Cycling profile was done in Thermal cycler PCR (Veriti® 96‐Well Thermal Cycler; Applied Biosystems) (Fig. 1). The resulting PCR products were sequenced by BigDyeTM Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit with a 310 Automated DNA Sequencer (Applied Biosystems). The obtained sequences were searched for identity using BLASTn. Electropherograms were analyzed using BioEdit 4.8.9. For phylogenetic study, the sequence data of COX1, ITS, and 18S rRNA fragments were installed into MEGA ver. 7.0. Phylogenetic trees were inferred using maximum likelihood (ML) with the Tamura-Nei model.

PCR thermal gradients for genetic markers COX1, ITS, and 18S rRNA.

3 Results

3.1 Natural prevalence of parasitic infections

Among the 30 Argyrops spinifer fish collected, 25 (83.33%) were naturally infected by three raphidascarid nematode parasites belonging to the genus Hysterothylacium. Former species was identified morphologically as the adult forms of Hysterothylacium reliquens Norris and Overstreet, 1975, while, second and third species as larval (fourth [L4] and third [L3]) stages. The adult species and L4 were frequently found on the stomach and intestine, and L3 larvae in the pyloric caeca of infected fish. Mean intensity and mean abundance of infection were 1.96 and 1.63, respectively. The amplitude of variation was between 12 and 20 parasite specimens/host.

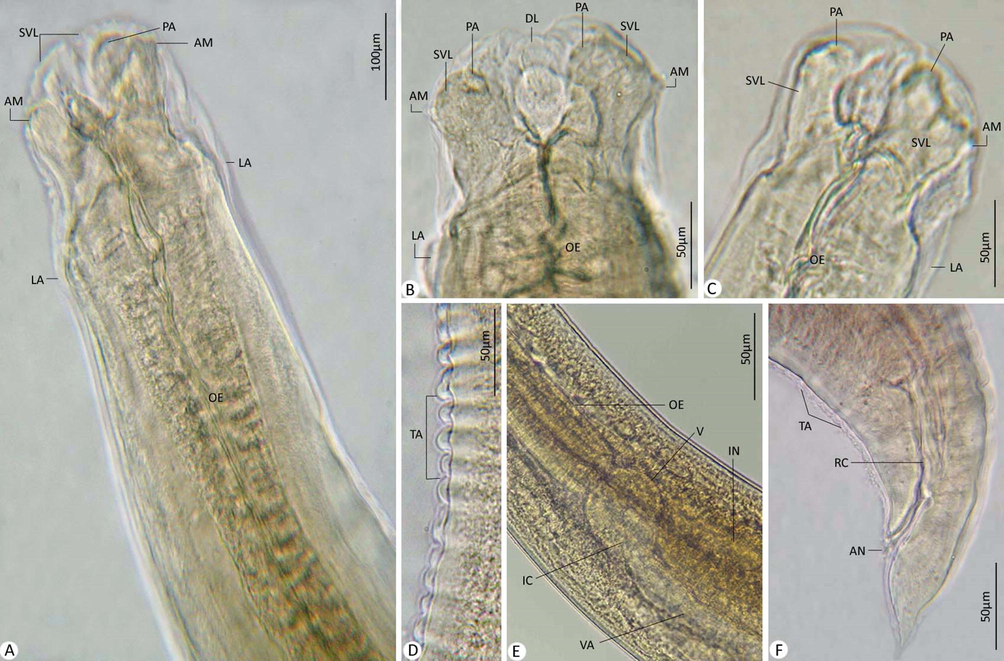

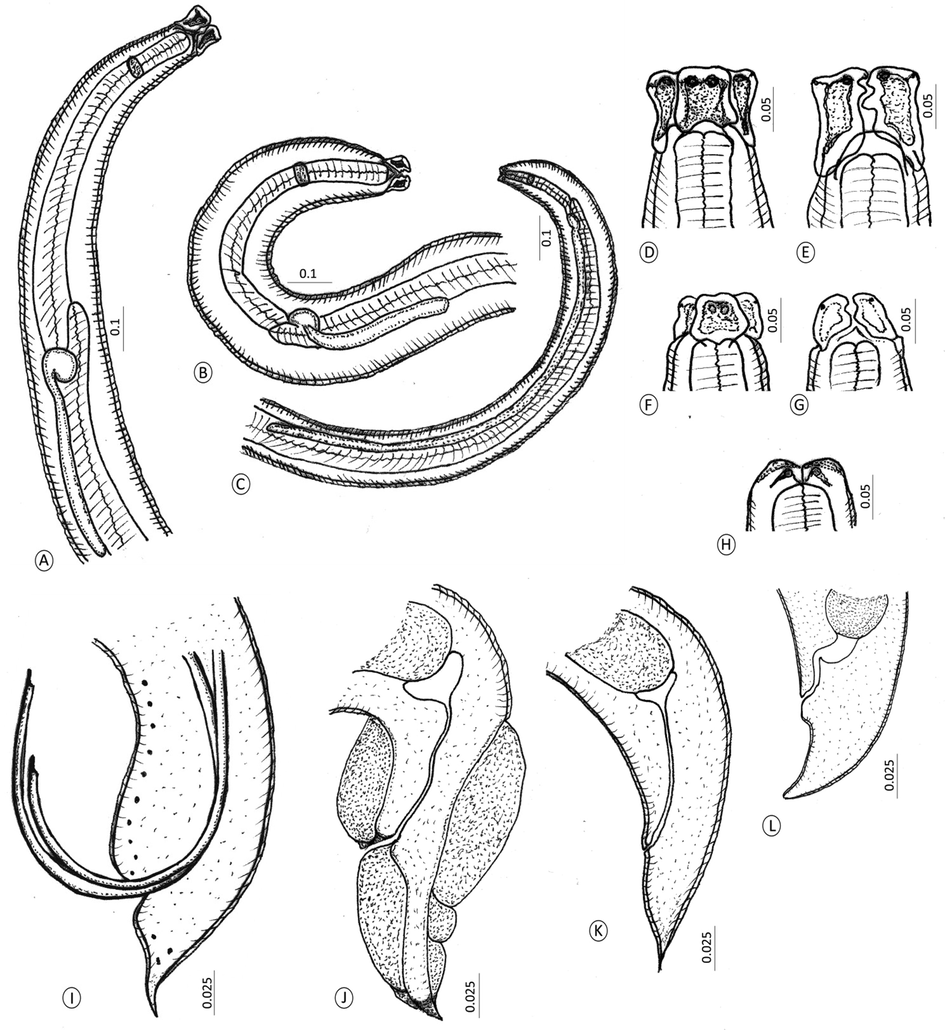

3.2 Morphology of adult forms (Figs. 2, 5)

Adult worms with an elongated cylindrical body and anterior end with mouth opening surrounded by three lips, one dorsal and two ventrolateral ones, which interlocked leaving interlabia in between. Lips with papillae-like structures, two double papillae on dorsal labium, and each subventral labia with one lateral amphid, one single, and one double papilla. Lateral alae extend from the base of subventral labia to the base of the tail tip. Cuticle transversally striated. Long muscular oesophagus, slightly broader posteriorly than anteriorly, and ended in small spherical ventriculus, and narrow ventriculus appendix. Intestinal caecum slightly shorter than ventriculus appendix. Excretory pore just behind level of the nerve ring. The tail of both sexes tipped by a single minute thorn called mucron.

Photomicrographs for adult worms of H. reliquens. (A-D) Anterior extremity of the body. (E) Transversely annulated cuticle. (F) Lateral alae. (G) Posterior extremity of female. (H-M) Posterior extremity of male. Note: ACP, adcloacal papillae; AM, amphid; AN, anus; CL, cloacal; DL, dorsal labium; IC, intestinal caecum; IN, intestine; LA, lateral alae; MU, mucron; OE, oesophagus; PA, papillae; PCP, precloacal papillae (mentioned by black arrows in H and J); POCP, postcloacal papillae; RC, rectum; RG, rectal gland(s); SP, spicule(s); SVL, subventral labium; TA, transverse annulations; UT, uterus; V, ventriculus; VA, ventriculus appendix.

3.2.1 Description of adult male worm (Based on 3 mature ♂ specimens) (Table 1)

Body 19.50–48.10 (30.89) long; maximum width 0.42–0.95 (0.65). Dorsal labium 0.160–0.250 (0.190) long, 0.150–0.270 (0.200) wide. Subventral labia 0.120–0.260 (0.180) long, 0.090–0.180 (0.133) wide. Oesophagus 2.30–4.10 (3.90) long. Nerve-ring and excretory pore 0.50–0.88 (0.75) and 0.59–0.99 (0.85), respectively, from anterior extremity. Ventriculus 0.18–0.30 (0.24) long. Ventricular appendix 0.96–1.95 (1.40) long. Intestinal caecum 0.30–0.55 (0.47) long. Posterior end of body curves ventrally. Spicules unequal and alate. Left spicule 1.30–1.85 (1.60) in length while right one 1.25–2.10 (1.83) long. Caudal papillae very small, arranged as 22–30 pairs of precloacal, 1 adcloacal, and 3–4 pairs of postcloacal. Tail 0.15–0.24 (0.18) long with numerous spines.

Morphometric character

Norris and Overstreet (1975)

Petter and Sey (1997)

Al-Salim and Ali (2010)

Zhao et al. (2017)

Ghadam et al. (2017)

Present study

Hosts

Archosargus probatocephalus, Chilomycterus

schoepfi, Halichoeres bivittatus, Micropogon

undulatus

Acanthopagrus berda, Epinephelus tauvina,

Elisha elongate, Polydavtylus sextarius,

Plotosus anguillaris, Pseudorhombus arsius,

Synaptura orientalis, Therapon puta, Trachinotus

blochi

Cynoglossus arel, Lethrinus nebulosus, Trichiurus lepturus

Brachirus orientalis

Otolithes ruber,

Brachirus orientalis

Argyrops spinifer

Locality

Mississippi, Biscayne Bay, Florida

Fish market, Kuwait

Khor Al-Ummia, Iraq

Persian Gulf, off

Basrah, southern

IraqKhor Abdulla,

IraqJeddah, Saudi Arabia

Body length

21.00–79.00

18.00–54.75 (40.28)

14.087–51.942 (26.796)

12.6–38.1 (25.10)

17.23–34.78 (23.81)

19.50–48.10 (30.89)

Body width

0.519–1.880

–

0.380–0.847 (0.613)

0.29–0.98 (0.631)

0.40–0.75 (0.60)

0.42–0.95 (0.65)

Lips size

Equal

0.148–0.382 × 0.168–0.490–

Sub-equal

Dorsal: 0.100–0.422 (0.182) × 0.065–0.288 (0.113)

Subventral: 0.085–0.402 (0.176) × 0.054–0.257 (0.128)Equal

0.132–0.330 (0.217) × 0.123–0.330 (0.207)Sub-equal

Dorsal: 0.15–0.24 (0.17) × 0.12–0.25 (0.17)

Subventral: 0.10–0.25 (0.16) × 0.05–0.13 (0.08)Sub-equal

Dorsal: 0.160–0.250 (0.190) × 0.150–0.270 (0.200)

Subventral: 0.120–0.260 (0.180) × 0.090–0.180 (0.133)

Distance of nerve ring to anterior end

0.544–0.721

0.45–1.05

0.422–0.690 (0.565)

0.490–1.080 (0.749)

0.46–0.83 (0.60)

0.50–0.88 (0.75)

Distance of excretory pore to anterior end

0.480–1.568

0.47–1.15

0.515–0.729 (0.646)

0.588–1.150 (0.783)

0.51–0.90 (0.65)

0.59–0.99 (0.85)

Oesophagus length

2.20–9.70

2.10–6.00 (4.33)

1.827–4.789 (2.939)

1.47–4.73 (3.37)

1.90–3.78 (2.57)

2.30–4.10 (3.90)

Ventriculus length

0.064–0.392

–

0.082–0.250 (0.123)

0.074–0.300 (0.170)

0.14–0.20 (0.16)

0.18–0.30 (0.24)

Ventricular appendix length

0.940–3.360

0.89–2.70 (1.71)

1.110–2.223 (1.660)

0.74–2.00 (1.46)

0.98–1.40 (1.16)

0.96–1.95 (1.40)

Length of intestinal caecum

0.255–1.400

0.36–1.00 (0.675)

0.299–1.350 (0.488)

0.196–0.650 (0.419)

0.28–0.37 (0.30)

0.30–0.55 (0.47)

Spicules length

Equal

1.24–3.38Equal

1.20–2.95 (1.86)Equal

0.910–1.656 (1.363)Equal

0.70–2.61 (1.86)Sub-equal

Left: 1.29–1.77 (1.56)

Right: 1.26–2.42 (1.76)Sub-equal

Left: 1.30–1.85 (1.60)

Right: 1.25–2.10 (1.83)

Precloacal papillae (Number)

24–33 pairs

22–30 pairs

17–28 pairs

25–32 pairs

27–31 pairs

22–30 pairs

Precloacal papillae

0–1

0–1

0–1

0–1

0–1

0–1

Postcloacal papillae (Number)

4–6 pairs

4–9 pairs

4–10 pairs

3–6 pairs

3–4 pairs

3–4 pairs

Tail length

0.120–0.235

0.20–0.25 (2.07)

0.123–0.447 (0.201)

0.157–0.250 (0.197)

0.17–0.21 (0.19)

0.15–0.24 (0.18)

3.2.2 Description of adult female worm (Based on 3 mature ♀ specimens) (Table 2)

Body length 20.50–51.20 (34.15), maximum width 0.65–1.10 (0.76). Dorsal labium 0.070–0.360 (0.190) long and 0.060–0.280 (0.180) wide. Subventral labia 0.060–0.350 (0.160) long, 0.050–0.270 (0.155) wide. Oesophagus 2.55–5.90 (4.10) long. Nerve-ring and excretory pore 0.550–1.20 (0.95) and 0.610–1.30 (1.05), respectively, from anterior extremity. Ventriculus 0.20–0.35 (0.28) long. Ventricular appendix 1.30–2.35 (1.85) long. Intestinal caecum 0.220–0.470 (0.380) long. Vulva slit-like and located pre-equatorially at 4.920–11.310 (7.540). Muscular vagina directed posteriorly from vulva. Uterus coiled and empty from eggs. Rectum opened by anal opening and surrounded with rectal glands. Body terminated in a conical tail 0.240–0.590 (0.375) long with numerous spines.

Morphometric character

Norris and Overstreet (1975)

Petter and Sey (1997)

Al-Salim and Ali (2010)

Zhao et al. (2017)

Ghadam et al. (2017)

Present study

Hosts

Archosargus probatocephalus, Chilomycterus

schoepfi, Halichoeres bivittatus, Micropogon

undulatus

Acanthopagrus berda, Epinephelus tauvina,

Elisha elongate, Polydavtylus sextarius,

Plotosus anguillaris, Pseudorhombus arsius,

Synaptura orientalis, Therapon puta, Trachinotus

blochi

Cynoglossus arel, Lethrinus nebulosus, Trichiurus lepturus

Brachirus orientalis

Otolithes ruber,

Brachirus

orientalis

Argyrops spinifer

Locality

Mississippi, Biscayne Bay, Florida

Fish market, Kuwait

Khor Al-Ummia, Iraq

Persian Gulf, off Basrah, southern

IraqKhor Abdulla,

IraqJeddah, Saudi Arabia

Body length

23.00–127.00

16.3–74.00 (49.49)

8.39–51.94 (18.78)

26.00–57.6 (40.7)

5.30–48.45 (21.19)

20.50–51.20 (34.15)

Body width

0.480–2.440

–

0.234–0.761 (0.501)

0.613–1.890 (1.020)

0.15–1.08 (0.52)

0.65–1.10 (0.76)

Lips size

Equal

0.164–0.510 × 0.196–0.686–

Sub-equal

Dorsal: 0.081–0.279 (0.137) × 0.063–0.225 (0.095)

Subventral: 0.078–0.243 (0.129) × 0.063–0.225 (0.095)Equal

0.211–0.400 (0.285) × 0.221–0.330 (0.270)Sub-equal

Dorsal: 0.05–0.33 (0.16) × 0.04–0.26 (0.14)

Subventral: 0.05–0.33 (0.17) × 0.03–0.23 (0.09)Sub-equal

Dorsal: 0.070–0.360 (0.190) × 0.060–0.280 (0.180)

Subventral: 0.060–0.350 (0.160) × 0.050–0.270 (0.155)

Distance of nerve ring to anterior end

–

0.50–1.15

0.276–0.659 (0.437)

0.588–2.320 (1.052)

0.25–1.01 (0.53)

0.550–1.20 (0.95)

Distance of excretory pore to anterior end

4.80–2.019

0.55–1.32

0.304–0.731 (0.488)

0.662–2.400 (1.078)

0.28–1.12 (0.58)

0.610–1.30 (1.05)

Oesophagus length

2.4–11.6

1.70–7.96 (5.71)

0.618–2.36 (2.03)

2.45–6.71 (3.98)

0.78–4.91 (2.36)

2.55–5.90 (4.10)

Ventriculus length

0.076–0.421

–

0.065–0.171 (0.110)

–

0.06–0.28 (0.16)

0.20–0.35 (0.28)

Ventricular appendix length

0.880–4.450

0.55–2.70 (1.84)

0.639–1.848 (1.256)

1.00–2.20 (1.62)

0.42–1.94 (1.06)

1.30–2.35 (1.85)

Length of intestinal caecum

0.26–1.80

0.47–1.40 (0.93)

0.234–0.408 (0.323)

0.368–0.650 (0.469)

0.18–0.56 (0.35)

0.220–0.470 (0.380)

Distance of vulva from anterior end

7.6–33.0

–

0.325–10.476 (6.943)

5.32–17.8 (10.5)

11.8–16.8 (14.3)

4.920–11.310 (7.540)

Tail length

0.300–0.686

0.19–0.55 (0.45)

0.144–0.378 (0.334)

0.363–0.500 (0.423)

0.15–0.57 (0.33)

0.240–0.590 (0.375)

3.3 Morphology of larval forms

.

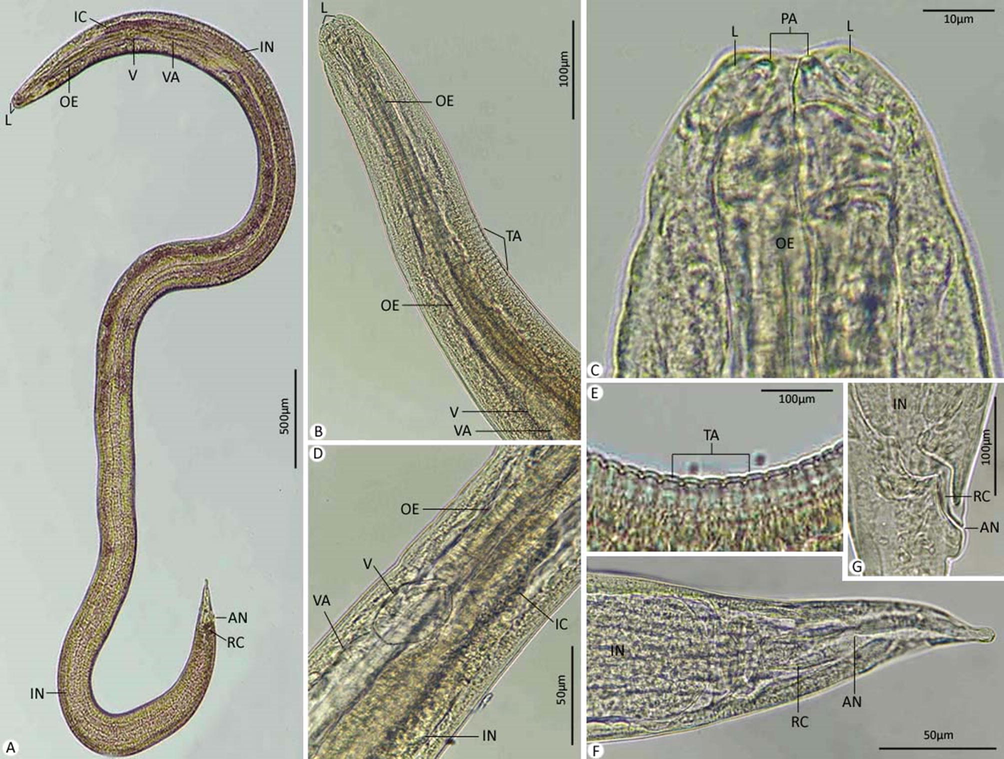

3.3.1 Description of L4 larvae (Based on 2 specimens) (Figs. 3, 5)

Body length 15.23–19.43 (18.21); 0.14–0.35 (0.29) maximum width. It had three distinct lips with short interlabia. Dorsal labium had a couple of large papillae and 0.04–0.08 (0.06) long, 0.03–0.06 (0.05) wide, each ventrolateral labia had a couple of papillae and an amphid, 0.05–0.08 (0.07) long, 0.03–0.07 (0.06) wide. Oesophagus 0.654–1.120 (0.95) long. Nerve ring and excretory pore 0.285–0.364 (0.310) and 0.350–0.420 (0.400), respectively, from anterior end. Cuticle striated transversely. Ventriculus 0.041–0.097 (0.84) long. Ventricular appendix 0.800–0.950 (0.910) long. Intestinal caecum 0.130–0.299 (0.256) long. Body ended in a long cactus-like tail of 0.110–0.240 (0.180) long.

Photomicrographs for L4. (A-C) Anterior extremity. (E) Cuticle with transverse annulations. (E) Ventriculus, ventricular appendix, and intestinal caecum. (F) Posterior extremity. Note: AM, amphid; AN, anal opening; DL, dorsal labium; IC, intestinal caecum; IN, intestine; LA, lateral alae; OE, oesophagus; PA, papillae; RC, rectum; SVL, subventral labia; TA, transverse annulations; V, ventriculus; VA, ventricular appendix.

3.3.2 Description of L3 larvae (Based on 2 specimens) (Figs. 4, 5)

Body 5.32–8.97 (6.20) long; 0.15–0.64 (0.48) wide. Anterior extremity of poorly developed labia provided with papillae and amphids. Cuticle annulated transversely. Nerve ring and excretory pore located from the anterior end at 0.091–0.229 (0.211) and 0.110–0.392 (0.310), respectively. Oesophagus 0.433–1.20 (0.95) long. Ventriculus spherical and 0.055–0.130 (0.09) long. Ventricular appendage 2.31–3.34 (2.28) long. Intestinal caecum shorter than the ventricular appendix and 0.188–0.205 (0.195) long. Tail pointed with a nodular protuberance, 0.164–0.197 (0.185) long.

Photomicrographs for L3. (A) Whole-mount preparation. (B-D) Anterior extremity. (E) Cuticle with transverse annulations. (F,G) Posterior extremity. Note: AN, anus; IC, intestinal caecum; IN, intestine; L, labium; MU, mucron; OE, oesophagus; PA, papillae; RC, rectum; TA, transverse annulations; V, ventriculus; VA, ventriculus appendix.

Line drawings for developmental stages of the recovered Hysterothylacium species. (A-C) Anterior ends of (A) Adults. (B) Fourth-stage larva. (C) Third-stage larvae. (D) Doral labium of adults. (E) Subventral labia of adults. (F) Dorsal labium of L4. (G) Subventral labia of L4. (H) Labia of L3. (I-L) Posterior end of (I) Male worm. (J) Female worm. (K) Fourth-stage larva. (L) Third-stage larvae.

3.4 Molecular analysis

A total of 546 bp of the ITS gene region was deposited in GenBank (MZ148786.1), with a GC content of 53.5%. In the case of the 18S rRNA gene region, the sequence derived from the current species was 709 bp with 49.2% GC content deposited in GenBank (MZ148788.1). In addition, the sequence of the COX1 gene region was 501 bp with 38.9% GC content deposited in GenBank (MZ148789.1). Pairwise comparison of isolated genomic sequences for present species with a variety of alternative class species and genotypes disclosed unique genetic sequences.

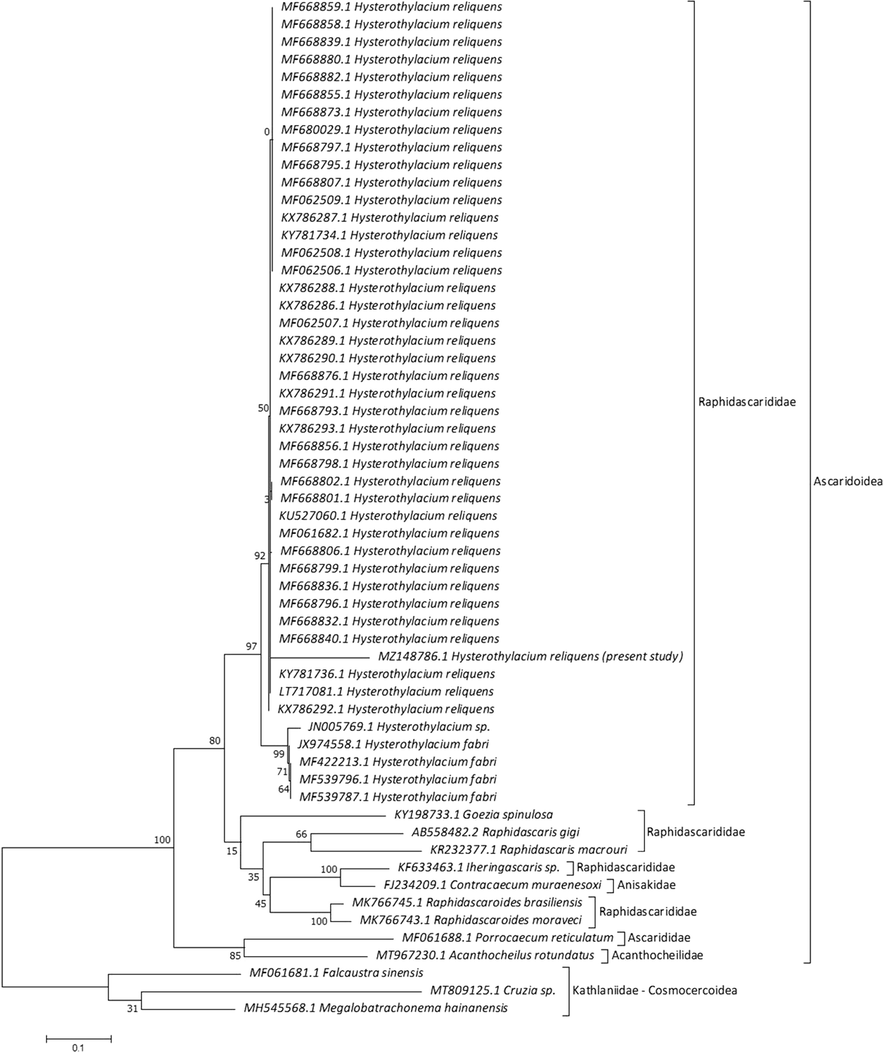

For the ITS gene region, the present species yielded the highest BLAST scores and lowest divergence values with 90.80–94.38% and 0.073 to H. reliquens, 84.31% and 0.111 to Hysterothylacium sp., and 84.55–85.17% and 0.098 to H. fabri. A phylogenetic tree was computed automatically using 58 Ascaridoidea ITS sequences of H. reliquens with those of other species of Rhabditida nematodes available in GenBank and showed that this order is represented by two superfamilies within Ascaridomorpha, were Ascaridoidea, and Cosmocercoidea (Fig. 6). The range of identity percentage and divergence values for the current specimen and others within Ascaridoidea was 65.83–94.38% and 0.073–1.073, while for those with Cosmocercoidea were 86.49–95.06% and 1.033–1.415, respectively. Raphidascarididae formed a sister group to Anisakidae with strong nodal support (1 0 0). A strong association reached to be 100 between Ascarididae and Acanthocheilidae. MP tree revealed that all Hysterothylacium species are grouped in a monophyletic clade with a high bootstrap value (97). Raphidascaris and Contracaecum species are in particular clusters basal to Hysterothylacium group. Our analysis investigated placement of the current species within Rhabditida, especially within Hysterothylacium with a close relationship to previously described H. reliquens in the same clade.

Molecular Phylogenetic analysis for ITS region by ML method.

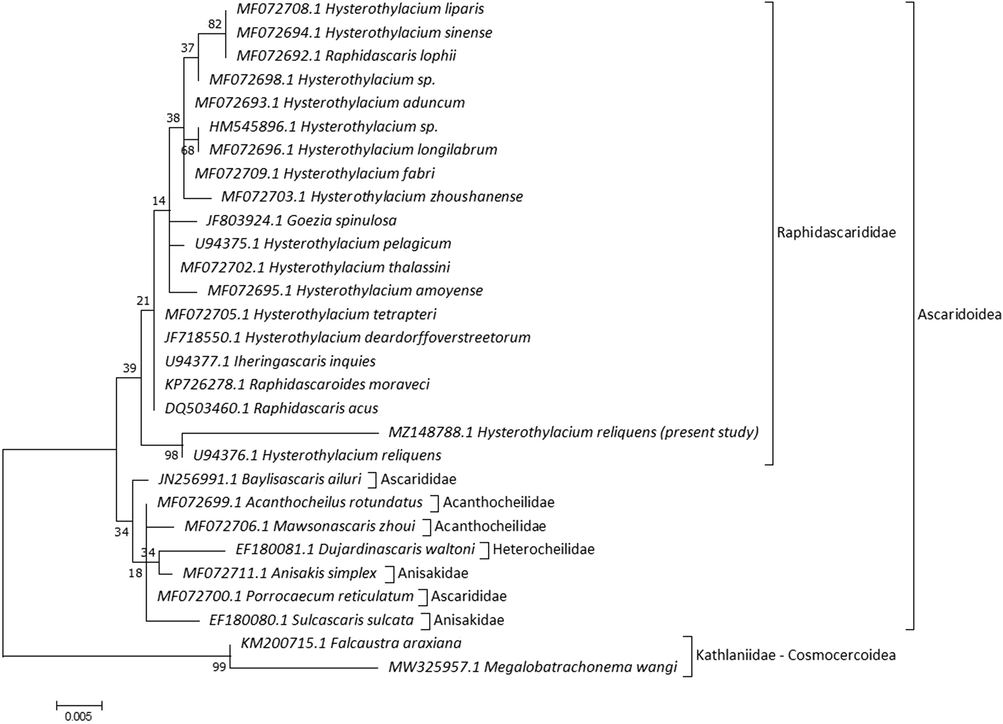

18S rRNA sequences for current specimens were matched with Hysterothylacium species available on GenBank with low genetic distances, with 97.88% and 0.022 to H. reliquens, 96.90% and 0.032 to H. liparis, 96.90% and 0.032 to H. sinense, 96.90% and 0.032 to Hysterothylacium sp., 97.04% and 0.031 to H. aduncum, 96.76% and 0.032 to H. longilabrum, 97.04% and 0.031 to H. fabri, 97.04% and 0.031 to H. zhoushanense, 97.04% and 0.031 to H. pelagicum, 97.18% and 0.029 to H. thalassini, 96.90% and 0.032 to H. amoyense, 97.32% and 0.028 to H. tetrapteri, and 97.32% and 0.028 to H. deardorffoverstreetorum. The current specimens revealed low divergence values with other Raphidascaridids, including Raphidascaris lophii (0.032), Raphidascaris moraveci (0.028), Raphidascaris acus (0.028), Iheringascaris inquires (0.028), and Goezia spinulosa (0.032). MP tree showed 29 nucleotide sequences and splitted into two main lineages (Fig. 7). The first lineage included two subclades with a range of identity and divergence as 96.76–97.88% and 0.022–0.038, the first one clustered current Hysterothylacium and taxa of Raphidascarididae, and the second subclade clustered remaining comparable species within Ascaridoidea. The second lineage included species related to Kathlaniidae within Cosmocercoidea with 92.10–93.37% and 0.066–0.084. Ascarididae formed a sister group with lower nodal support to Anisakidae + Heterocheilidae + Acanthochelidae. Our analysis investigated placement of examined species within Raphidascarididae and deeply embedded in Hysterothylacium with close association (98) to previously described H. reliquens in the same taxon. Hysterothylacium was not monophyletic, with a clade containing Hysterothylacium spp., R. acus, R. moraveci, I. inquies, and G. spinulosa, and another clustering H. reliquens.

Molecular Phylogenetic analysis for 18S rRNA by ML method.

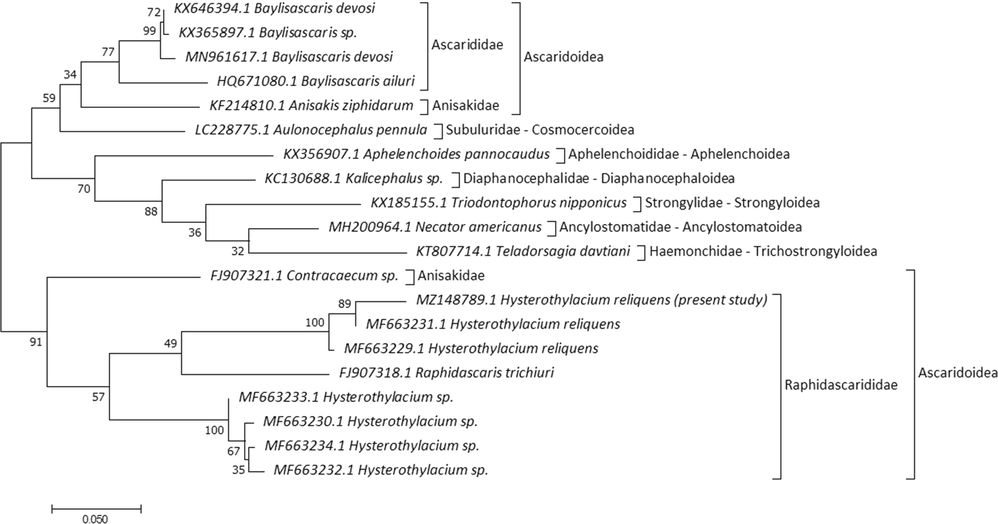

COX1 sequences for current specimens were matched with other Hysterothylacium species in GenBank with low divergence values, with H. reliquens (97.21% and 0.027), 83.37% and 0.206 to Hysterothylacium sp., and 82.83% and 0.218 to Raphidascaris trichiuri. Tree topology is based on 20 COX1 sequences and distributed into two main lineages (Fig. 8). The first lineage was divided into two subclades; the first one clustered the most closely related families within Rhabditida with 79.80–84.23% and 0.195–0.256 for identity and divergence values, respectively. Anisakidae and Ascarididae formed a sister group to Subuluridae with moderate nodal support (62). The second subclade clustered species of four families within Strongylida with 80.44–81.80% and 0.225–0.272 for identity and divergence, respectively. The second lineage included the closest species within Raphidascarididae and Anisakidae with a close association (90), similarity index and divergence values were 80.72–97.21% and 0.206–0.221. On the MP tree, a genus-specific cluster with a well-support value was delineated in genera Raphidascaris, Contracaecum, and Hysterothylacium. The current topology allocated current specimens within Raphidascarididae with a moderate supported value (57) to other Hysterothylacium species with close relation to previously H. reliquens in the same taxon.

Molecular Phylogenetic analysis for COX1 by ML method.

4 Discussion

Assemblages of the marine fish harbor a significant number of larval stages of helminth taxa that use fish as intermediate or sometimes as definitive hosts (Shih and Jeng, 2002). It is important to study the biodiversity and relative abundance of ascaridoids. The present study provides the first report of Argyrops spinifer harbored both larval and adult raphidascarids. Combination of morphological features including the shape of lips with interlabia, posterior location of the excretory pore to nerve ring, a lower ratio of intestinal caecum to ventricular appendix length, spicules length exceeding 1 mm, and number and distribution of caudal papillae, identify the recovered species from Argyrops spinifer as belonging to genus Hysterothylacium. Although, presence of many Hysterothylacium species, many of them need to be further studied using updated techniques to determine exact taxonomic status.

The present study reported the high prevalence of L4 and adult specimens in the digestive tract of infected fish, while the pyloric caeca are highly parasitized by L3, this agreed with Køie (1993). In addition, the morphology and morphometry of the present adult specimens are almost identical to the original description of H. reliquens Norris and Overstreet (1975) infecting A. probatocephalus (type host) and other fish species in the northern Gulf of Mexico and southern Florida, and this species revised in 1981 by Deardoff and Overstreet’s. This raphidascaridid was later reported by Petter and Sey (1997), Al-Salim and Ali (2010), Ghadam et al. (2017), and Zhao et al. (2017) from the Persian Gulf off Kuwait and Iraq. Regarding the number of postcloacal papillae, Petter and Sey (1997) and Al-Salim and Ali (2010) stated the observation of up to nine pairs, which is much more than that of specimens of Norris and Overstreet (1975), Deardorff and Overstreet (1981), Ghadam et al. (2017), Zhao et al. (2017) and the current specimens.

Regarding Chen et al. (2018), four different morphotypes for Hysterothylacium larvae were distinguished based on the relative length of the intestinal caecum and ventricular appendix, and morphology of tail extremity. However, it is problematic to identify the morphology of larval morphotypes to species level, thus molecular tools were used for the exact identification of species. Herein, two larval stages of L4 and L3 with adult forms were observed in studied host species, which agreed with Moravec et al. (1997) stated the occurrence of L4 in the same host which harbored adult was common. Herein, L4 similar to Hysterothylacium L4 type of Deardorff and Overstreet (1981), Hysterothylacium L4 type of Al-Salim and Ali (2010), and Hysterothylacium larval type XVI of Ghadam et al. (2017) based on the presence of minute spinous structures on tail tip and lengths of different structures concerning total body length. Also, the current L3 is similar to Hysterothylacium sp. type BC larva of Al-Salim and Ali (2010), and Hysterothylacium larval type XV of Ghadam et al. (2017) in which lateral alae and multispinous structure in the tail are absent, and position of excretory pore just behind nerve ring.

Morphological identification of the recovered specimens was also supported by molecular analyses. This agreed with Zhao et al. (2017) stated the usage of genetic markers especially ITS in combination with morphological features to elucidate accurate identification for ascaridoids. Herein, molecular analysis showed lower divergence values between current specimens and other Hysterothylacium species (for 18S rRNA 0.022–0.032, ITS 0.073–0.111, and COX1 0.027–0.206), which agreed with Zhao et al. (2017) stated these lower values related to intraspecific nucleotide variation which strongly supported broad ranges of morphological variability in Hysterothylacium species related to geographical localities. Our results showed that the COX1 gene revealed a major intraspecific variation among Hysterothylacium species which confirmed high variability of COX region compared with ITS region, this agreed with Costa et al. (2018).

Concerning the relationships between congeners, the current specimens, Hysterothylacium spp., R. acus, R. moraveci, I. inquies, and G. spinulosai are in a polytomy on the 18S rRNA tree, which is consistent with Smythe et al. (2006) observed the splitting of Hysterothylacium species into two clades, one of which clustered H. pelagicum, R. acus, I. inquires, and G. pelagia. 18S rRNA topology showed Iheringascaris is best represented as more closely related to Hysterothylacium, which agreed with Nadler and Hudspeth (2000). Phylogenetic analysis of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) COX1 dataset supports the current Hysterothylacium specimen as an evolutionary separate taxon with the previously H. reliquens. The use of COX1 herein corroborates the value of this genetic marker as a barcode for molecular taxonomy, allowing the identification of closely related anisakid nematodes, this agreed with Mattiucci et al. (2009). 18S rRNA and COX1 gene analyses were in agreement with Knoff et al. (2012) stated Hysterothylacium does not represent a monophyletic group, since the presence of Pseudoterranova decipiens and R. trichiuri suggest the existence of a polyphyletic group for Hysterothylacium species. However, different from ITS topology, Hysterothylacium genus-specific cluster is formed by H. reliquens, Hysterothylacium sp., and H. fabri. Topology analyses with partial sequences of ITS and COX1 showed that Raphidascarididae formed a sister group to Anisakidae with low genetic variations between them, this data agreed with Al Quraishy et al. (2019). 18S rRNA demonstrated that species of the Heterocheilidae form a sister group to remaining Ascaridoids, which is consistent with Li et al. (2018). Also, the COX1 gene indicated relationships of Anisakidae and Ascarididae with Subuluridae, which is consistent with Kalyanasundaram et al. (2017).

5 Conclusion

The present study provided valuable information about a nematode species Hysterothylacium reliquens, which can infect Argyrops spinifer. Detailed morphological characterization, along with the characterization of ITS region, 18S rRNA, COX1 genes, can be useful for future taxonomical and systematics studies of raphidascaridids. Future studies using different genetic markers are required to examine genetic variability for larvae of Hysterothylacium species within this fish host. In addition, explore the remaining parasitic taxa infecting different tissues of Argyrops spinifer.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Prince Sattam Bin Abdulaziz University under the research project #2019/01/10971.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- First record of Pseudoterranova decipiens (Nematoda, Anisakidae) infecting the Red spot emperor Lethrinus lentjan in the Red Sea. Braz. J. Vet. Parasitol.. 2019;28(4):625-631.

- [Google Scholar]

- Description of eight nematode species of the genus Hysterothylacium Ward et Magath, 1917 parasitized in some Iraqi marine fishes. Basrah J. Agric. Sci.. 2010;23(1):115-137.

- [Google Scholar]

- DNA Barcoding and Morphological Identification of Benthic Nematodes Assemblages of Estuarine Intertidal Sediments: Advances in Molecular Tools for Biodiversity Assessment. Front. Mar. Sci.. 2017;4:66.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ribosomal RNA Probes for Detection and Identification of Species. In: Hyde J.E., ed. Protocols in Molecular Parasitology. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 1993. p. :249-263.

- [Google Scholar]

- Human health, legislative and socioeconomic issues caused by the fish-borne zoonotic parasite Anisakis: Challenges in risk assessment. Trends Food Sci. Tech.. 2019;86:298-310.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hysterothylacium aduncum (Nematoda) in fish. ICES Identification leaflets for diseases and parasites of fish and shellfish. Leaflet No.. 1991;44:4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Parasitology meets ecology on its own terms: Margolis et al revisited. J. Parasitol.. 1997;83:575-583.

- [Google Scholar]

- Detection of ascaridoid nematode parasites in the important marine food-fish Conger myriaster (Brevoort) (Anguilliformes: Congridae) from the Zhoushan Fishery. China. Parasit Vectors. 2018;11:274.

- [Google Scholar]

- Molecular identification of Hysterothylacium spp. in fishes from the Southern Mediterranean Sea (Southern Italy) J. Parasitol.. 2018;104(4):398-406.

- [Google Scholar]

- Larval Hysterothylacium (=Thynnascaris) (Nematoda: Anisakidae) from fishes and invertebrates in the Gulf of Mexico. Proc. Helmintho. Soc. Wash.. 1981;48(2):113-126.

- [Google Scholar]

- GBIF, 2021. https://www.gbif.org/species/2284252.

- Morphological and molecular characterization of selected species of Hysterothylacium (Nematoda: Raphidascarididae) from marine fish in Iraqi waters. J. Helminthol. 2017:1-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Molecular identification and characterization of partial COX1 gene from caecal worm (Aulonocephalus pennula) in Northern bobwhite (Colinus virginianus) from the Rolling Plains Ecoregion of Texas. Int. J. Parasitol.: Parasites Wildl.. 2017;6:195-201.

- [Google Scholar]

- Life cycle strategy of Hysterothylacium aduncum to become the most abundant anisakid fish nematode in the North Sea. Parasitol. Res.. 2005;97(2):141-149.

- [Google Scholar]

- Genetic and morphological characterisation of a new species of the genus Hysterothylacium (Nematoda) from Paralichthys isosceles Jordan, 1890 (Pisces: Teleostei) of the Neotropical Region, state of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz, Rio de Janeiro. 2012;107(2):186-193.

- [Google Scholar]

- Aspects of the life-cycle and morphology of Hysterothylacium aduncum (Rudolphi, 1802) (Nematoda, Ascaridoidea, Anisakidae) Can. J. Zool.. 1993;71:1289-1296.

- [Google Scholar]

- Molecular phylogeny and dating reveal a terrestrial origin in the early carboniferous for ascaridoid nematodes. Syst. Biol.. 2018;67(5):880-900.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hysterothylacium larvae (Naematoda, Anisakidae) in the freshwater mussel Diplodon suavidicus (Lea, 1856) (Mollusca, Unioniformes, Hyriidae) in Aripuanã River. J. Invertebr. Pathol.. 2011;106:357-359.

- [Google Scholar]

- A new primer set for amplification of COI mtDNA in parasitic nematodes. Russ. J. Nematol.. 2016;24(1):73-75.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anisakis nascettii n. sp. (Nematoda: Anisakidae) from beaked whales of the southern hemisphere: morphological description, genetic relationships between congeners and ecological data. Syst. Parasitol.. 2009;74:199-217.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hysterothylacium patagonense n. sp. (Nematoda: Anisakidae) from freshwater fishes in Patagonia, Argentina, with a key to the species of Hysterothylacium in American freshwater fishes. Syst. Parasitol.. 1997;36:31-38.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phylogeny of the Ascaridoidea (Nematoda: Ascaridida) based on three genes and morphology: hypotheses of structural and sequence evolution. J. Parasitol.. 2000;86:380-393.

- [Google Scholar]

- Thynnascaris reliquens sp. n. and Thynnascaris habena (Linton, 1900) (Nematoda: Ascaridoidea) from fishes in Northern Gulf of Mexico and eastern US seaboard. J, Parasitol.. 1975;61:330-336.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nematode parasites of marine fishes from Kuwait, with a description of Cucullanus trachinoti n. sp. from Trachinotus blochi. Zoosystema. 1997;19:35-59.

- [Google Scholar]

- Quelques nématodes parasites des reptiles. Bull. Soc. Pathol. Exot.. 1912;4:251-259.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fortsetzung der Beobachtungen ueber die Eingeweidewuermer. Arch Zool. U Zool.. 1802;2:65.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hysterothylacium aduncum (Nematoda: Anisakidae) infecting a herbivorous fish, Siganus fuscescens, off the Taiwanese coast of the Northwest Pacific. Zool. Stud.. 2002;41:208-215.

- [Google Scholar]

- Identification and molecular characterization of Hysterothylacium (Nematoda: Raphidascarididae) larvae in bogue (Boops boops L.) from the Aegean Sea. Turkey. Kafkas Univ. Vet. Fak. Derg.. 2018;24:525-530.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nematode small subunit phylogeny correlates with alignment parameters. Syst. Biol.. 2006;55:972-992.

- [Google Scholar]

- FAO species identification field guide for fishery purposes. FAO, Rome: The living marine resources of Somalia; 1996. p. :376.

- WoRMS, 2021. https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=19962.

- Morphological variability, ultrastructure and molecular characterisation of Hysterothylacium reliquens (Norris & Overstreet, 1975) (Nematoda: Raphidascarididae) from the oriental sole Brachirus orientalis (Bloch & Schneider) (Pleuronectiformes: Soleidae) Parasitol. Int.. 2017;66:831-838.

- [Google Scholar]